Abstract

Introduction

Prospective pharmacovigilance aims to rapidly detect safety concerns related to medical products. The exposure model selected for pharmacovigilance impacts the timeliness of signal detection. However, in most real-life pharmacovigilance studies, little is known about which model correctly represents the association and there is no evidence to guide the selection of an exposure model. Different exposure models reflect different aspects of exposure history, and their relevance varies across studies. Therefore, one potential solution is to apply several alternative exposure models simultaneously, with each model assuming a different exposure–risk association, and then combine the model results.

Methods

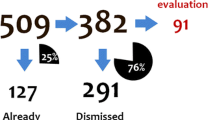

We simulated alternative clinically plausible associations between time-varying drug exposure and the hazard of an adverse event. Prospective surveillance was conducted on the simulated data by estimating parametric and semi-parametric exposure–risk models at multiple times during follow-up. For each model separately, and using combined evidence from different subsets of models, we compared the time to signal detection.

Results

Timely detection across the simulated associations was obtained by fitting a set of pharmacovigilance models. This set included alternative parametric models that assumed different exposure–risk associations and flexible models that made no assumptions regarding the form/shape of the association. Times to detection generated using a simple combination of evidence from multiple models were comparable to those observed under the ideal, but unrealistic, scenario where pharmacovigilance relied on the single ‘true’ model used for data generation.

Conclusions

Simulation results indicate that, if the true model is not known, an association can be detected in a more timely manner by first fitting a carefully selected set of exposure–risk models and then generating a signal as soon as any of the models considered yields a test statistic value below a predetermined testing threshold.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Harpaz R, DuMouchel W, LePendu P, Bauer-Mehren A, Ryan P, Shah NH. Performance of pharmacovigilance signal-detection algorithms for the FDA adverse event reporting system. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93:539–46.

Franklin JM, Schneeweiss S, Polinski JM, Rassen JA. Plasmode simulation for the evaluation of pharmacoepidemiologic methods in complex healthcare databases. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2014;72:219–26.

Kesselheim AS, Gagne JJ. Strategies for post marketing surveillance of drugs for rare diseases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95:265–8.

Trifiro G, Coloma PM, Rijnbeek PR, Romio S, Mosseveld B, Weibel D, et al. Combining multiple healthcare databases for postmarketing drug and vaccine safety surveillance: why and how? J Intern Med. 2014;275:551–61.

Bartlett G, Abrahamowicz M, Grad R, Sylvestre M-P, Tamblyn R. Association between risk factors for injurious falls and new benzodiazepine prescribing in elderly persons. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:1.

Christensen L, Sasané R, Hodgkins P, Harley C, Tetali S. Pharmacological treatment patterns among patients with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: retrospective claims-based analysis of a managed care population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:977–89.

Abrahamowicz M, Beauchamp M-E, Sylvestre M-P. Comparison of alternative models for linking drug exposure with adverse effects. Stat Med. 2012;31:1014–30.

Nelson JC, Cook AJ, Onchee Y, Zhao S, Jackson LA, Psaty BM. Methods for observational post-licensure medical product safety surveillance. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015;24:177–93.

McMahon AD, Evans JMM, McGilchrist MM, McDevitt DG, MacDonald TM. Drug exposure risk windows and unexposed comparator groups for cohort studies in pharmacoepidemiology. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1998;7:275–80.

Csajka C, Verotta D. Pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic modelling: history and perspectives. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2006;33:227–79.

Karimi G, Star K, Noren NG, Hagg S. The impact of duration of treatment of reported time-to-onset in spontaneous reporting systems for pharmacovigilance. PLOS One. 2013;8:e68938.

Kiri VA. A pathway to improved prospective observational post-authorization safety studies. Drug Saf. 2012;35:711–24.

Fireman B, Toh S, Butler MG, Go AS, Joffe HV, Graham DJ, et al. A protocol for active surveillance of acute myocardial infarction in association with the use of a new antidiabetic pharmaceutical agent. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;21:282–90.

Harpaz R, DuMouchel W, Shah NH, Madigan D, Ryan P, Friedman C. Novel data-mining methodologies for adverse drug event discovery and analysis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:1010–21.

Motsko SP, Rascati KL, Busti AJ, Wilson JP, Barner JC, Lawson KA, et al. Temporal relationship between use of NSAIDs, including selective COX-2 inhibitors, and cardiovascular risk. Drug Saf. 2006;29:621–32.

Helin-Salmivaara A, Virtanen A, Vesalainen R, Grönroos JM, Klaukka T, Idänpään-Heikkilä JE, et al. NSAID use and the risk of hospitalization for first myocardial infarction in the general population: a nationwide case–control study from Finland. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1657–63.

Ray WA, Stein CM, Hall K, Daugherty JR, Griffin MR. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of serious coronary heart disease: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:118–23.

Ray WA, Varas-Lorenzo C, Chung CP, Castellsague J, Murray KT, Stein CM, et al. Cardiovascular risks of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in patients after hospitalization for serious coronary heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:155–63.

García Rodríguez LA, Varas-Lorenzo C, Maguire A, González-Pérez A. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction in the general population. Circulation. 2004;109:3000–6.

García Rodríguez LA, Tacconelli S, Patrignani P. Role of dose potency in the prediction of risk of myocardial infarction associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1628–36.

Tournier M, Bégaud B, Cougnard A, Auleley G-R, Deligne J, Blum-Boisgard C, et al. Influence of the drug exposure definition on the assessment of the antipsychotic metabolic impact in patients initially treated with mood-stabilizers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74:189–96.

Østbye T, Curtis LH, Masselink LE, Hutchison S, Wright A, Dans PE, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and diabetes mellitus in a large outpatient population: a retrospective cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:407–15.

Guo JJ, Keck PE, Corey-Lisle PK, Li H, Jiang D, Jang R, et al. Risk of diabetes mellitus associated with atypical antipsychotic use among Medicaid patients with bipolar disorder: a nested case–control study. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:27–35.

Cook AJ, Tiwari RC, D’Wellman R, Heckbert SR, Li L, Heagerty PJ, et al. Statistical approaches to group sequential monitoring of postmarket safety surveillance data: current state of the art for use in the mini-sentinel pilot. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:72–81.

Brown JS, Kulldorff M, Chan KA, Davis RL, Graham D, Pettus PT, et al. Early detection of adverse drug events within population-based health networks: application of sequential testing methods. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:1275–84.

Gagne JJ, Rassen JA, Walker AM, Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S. Active safety monitoring of new medical products using electronic healthcare data: selecting alerting rules. Epidemiology. 2012;23:238–46.

Perucca P, Gilliam FG. Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:792–802.

Stricker BHC, Stijnen T. Analysis of individual drug use as a time-varying determinant of exposure in prospective population-based cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:245–51.

Zaccara G, Franciotta D, Perucca E. Idiosyncratic adverse reactions to antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1223–44.

Van Gaalen RD, Abrahamowicz M, Buckeridge D. The impact of exposure model misspecification on the timeliness of signal detection in prospective pharmacovigilance. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:456–67.

Volinsky CT, Madigan D, Raftery AE, Kronmal RA. Bayesian model averaging in proportional hazard models: assessing the risk of a stroke. Appl Stat. 1997;46:433–48.

Hoeting JA, Madigan D, Raftery AE, Volinsky CT. Bayesian model averaging: a tutorial. Stat Sci. 1999;14:382–401.

Claeskens G, Hjort NL. Model selection and model averaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

Chen Z. Is the weighted z-test the best method for combining probabilities from independent tests? J Evol Biol. 2011;24:926–30.

Zaykin DV, Zhivotovsky LA, Westfall PH, Weir BS. Truncated product method for combining p-values. Genet Epidemiol. 2002;22:170–85.

Delongchamp R, Lee T, Velasco C. A method for computing the overall statistical significance of a treatment effect among a group of genes. BMC Bioinform. 2006;7(Suppl. 2):S11.

Zaykin DV. Optimally weighted Z-test is a powerful method for combining probabilities in meta analysis. J Evol Biol. 2011;24:1836–41.

Sylvestre M-P, Evans T, MacKenzie T, Abrahamowicz M. PermAlgo: permutational algorithm to generate event times conditional on a covariate matrix including time-dependent covariates. 2010; R package version 1.1..http://cran-mirror.cs.uu.nl/. Accessed 15 June 2017.

Sylvestre M-P, Abrahamowicz M. Comparison of algorithms to generate event times conditional on time-dependent covariates. Stat Med. 2008;27:2618–34.

Abrahamowicz M, Bartlett G, Tamblyn R, Du Berger R. Modeling cumulative dose and exposure duration provided insights regarding the associations between benzodiazepines and injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59:393–403.

Sylvestre M-P, Abrahamowicz M. Flexible modeling of the cumulative effects of time-dependent exposures on the hazard. Stat Med. 2009;28:3437–53.

Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Autom Control. 1974;19:716–23.

Mahmud M, Abrahamowicz M, Leffondré K, Chaubey YP. Selecting the optimal transformation of a continuous covariate in Cox’s regression: implications for hypothesis testing. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2006;35:27–45.

Saag KG, Koehnke R, Caldwell JR, Brasington R, Burmeister LF, Zimmerman B, et al. Low dose long-term corticosteroid therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of serious adverse events. Am J Med. 1994;96:115–23.

Franklin J, Lunt M, Symmons D, Silman A. Risk and predictors of infection leading to hospitalisation in a large primary-care-derived cohort of patients with inflammatory polyarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:308–12.

Lacaille D, Guh DP, Abrahamowicz M, Anis AH, Esdaile JM. Use of nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and risk of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1074–81.

Schneeweiss S, Setoguchi S, Weinblatt ME, Katz JN, Avorn J, Sax PE, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy and the risk of serious bacterial infections in elderly patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1754–64.

Smitten AL, Choi HK, Hochberg MC, Suissa S, Simon TA, Testa MA, et al. The risk of hospitalized infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:387–93.

Bernatsky S, Hudson M, Suissa S. Anti-rheumatic drug use and risk of serious infections in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2007;46:1157–60.

Benedetti A, Abrahamowicz M, Goldberg MS. Accounting for data-dependent degrees of freedom selection when testing the effect of a continuous covariate in generalized additive models. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38:1115–35.

Dudbridge F, Koeleman BPC. Efficient computation of significance levels for multiple associations in large studies of correlated data, including genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:424–35.

Conneely KN, Boehnke M. So many correlated tests, so little time! Rapid adjustment of p values for multiple correlated tests. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1158–68.

Dai H, Leeder JS, Cui Y. A modified generalized Fisher method for combining probabilities from dependent tests. Front Genet. 2014;5:32.

Dixon WG, Abrahamowicz M, Beauchamp M-E, Ray DW, Bernatsky S, Suissa S, et al. Immediate and delayed impact of oral glucocorticoid therapy on risk of serious infection in older patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a nested case–control analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1128–33.

Young J, Xiao Y, Moodie EEM, Abrahamowicz M, Klein M, Bernasconi E, et al. Effect of cumulating exposure to abacavir on the risk of cardiovascular disease events in patients from the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69:413–21.

Movahedi M, Beauchamp ME, Abrahamowicz M, Ray DW, Michaud K, Pedro S, et al. Risk of incident diabetes associated with dose and duration of oral glucocorticoid therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1089–98.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank two anonymous reviewers whose thoughtful reviews improved this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Grant MOP-81275.

Conflict of interest

Prior to May 2014, Rolina van Gaalen worked as a part-time intern at Pfizer Canada. The work presented in this paper is neither related to her work at Pfizer nor funded by Pfizer. Michal Abrahamowicz and David Buckeridge have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Gaalen, R.D., Abrahamowicz, M. & Buckeridge, D.L. Using Multiple Pharmacovigilance Models Improves the Timeliness of Signal Detection in Simulated Prospective Surveillance. Drug Saf 40, 1119–1129 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0555-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0555-9