Abstract

Introduction

The Self-Controlled Case Series (SCCS) method has been widely used for hypothesis testing, but there is limited evidence of its performance for safety signal detection.

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate SCCS for signal detection on recently approved products.

Methods

A retrospective study covered the period after three recently marketed drugs were launched through to 31 December 2010 using The Health Improvement Network, a UK primary care database, and Optum, a US claims database. The SCCS method was applied to examine five heterogenous outcomes with desvenlafaxine and escitalopram and six outcomes with adalimumab for Signals of Disproportional Recording (SDRs); a positive finding was determined to be when the lower bound of 95% Confidence Interval of the incidence rate ratio (IRR) estimate was > 1. Multiple design choices were tested and the trend in IRR estimates over calendar time for one drug event pair was examined.

Results

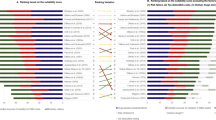

All six outcomes with adalimumab, three of five outcomes with desvenlafaxine, and four of five outcomes with escitalopram had SDRs. SCCS highlighted all acute events in the primary analysis but was less successful with slower-onset outcomes. Performance varied by risk period definition. Changes in IRR estimates over quarterly intervals for adalimumab with herpes zoster showed marked higher SDR within 9 months of drug launch.

Conclusion

SCCS shows promise for signal detection: it may highlight known associations for recent marketed products and has potential for early signal identification. SCCS performance varied by design choice and the nature of both exposure and event pair. Future work is needed to determine how effective the approach is in prospective testing and determining the performance characteristics of the approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Van De Carr SW, Kennedy DL, Rosa FW, et al. Relationship of oral contraceptive estrogen dose to age. Am J Epidemiol. 1983;117(2):153–9.

Strom BL, Carson JL, Morse ML, et al. The computerized on-line medicaid pharmaceutical analysis and surveillance system: a new resource for postmarketing drug surveillance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985;38(4):359–64.

Jick H, Jick SS, Derby LE. Validation of information recorded on general practitioner based computerised data resource in the United Kingdom. BMJ. 1991;302(6779):766–8.

Jones JK, Van de Carr SW, Rosa F, et al. Medicaid drug-event data: an emerging tool for evaluation of drug risk. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1984;683:127–34.

Bate A, Evans SJ. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(6):427–36.

Coloma PM, Trifirò G, Schuemie MJ, et al. Electronic healthcare databases for active drug safety surveillance: is there enough leverage? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:611–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.

Norén GN, Hopstadius J, Bate A, et al. Safety surveillance of longitudinal databases: results on real-world data [letter]. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(6):673–5.

Pacurariu AC, Straus SM, Trifirò G, et al. Useful interplay between spontaneous ADR reports and electronic healthcare records in signal detection. Drug Saf. 2015;38(12):1201–10.

Trifirò G, Pariente A, Coloma PM, et al. Data mining on electronic health record databases for signal detection in pharmacovigilance: which events to monitor? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(12):1176–84.

Zhou X, Murugesan S, Bhullar H, et al. An evaluation of the THIN database in OMOP common data model for active drug safety surveillance. Drug Saf. 2013;36:119–34.

Farrington CP. Relative incidence estimation from case series for vaccine safety evaluation. Biometrics. 1995;51:228–35.

Brauer R, Smeeth L, Anaya-Izquierdo K, et al. Antipsychotic drugs and risks of myocardial infarction: a self-controlled case series study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(16):984–92.

Douglas IJ, Evans SJ, Pocock S, et al. The risk of fractures associated with thiazolidinediones: a self-controlled case-series study. PLoS Med. 2009;6(9):e1000154.

Douglas IJ, Langham J, Bhaskaran K, et al. Orlistat and the risk of acute liver injury: self-controlled case series study in UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. BMJ. 2013;346:f1936.

Whitaker HJ, Farrington CP, Spiessens B, et al. Tutorial in biostatistics: the self-controlled case series method. Stat Med. 2006;25(10):1768–97.

Whitaker HJ, Hocine MN, Farrington CP, et al. The methodology of self-controlled case series studies. Stat Methods Med Res. 2009;18(1):7–26.

Grosso A, Douglas I, MacAllister R, et al. Use of the self-controlled case series method in drug safety assessment. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2011;10(3):337–40. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2011.562187.

Simpson SE, Madigan D, Zorych I, et al. Multiple self-controlled case series for large-scale longitudinal observational databases. Biometrics. 2013;69(4):893–902.

Suchard MA, Zorych I, Simpson SE, et al. Empirical performance of the self-controlled case series design: lessons for developing a risk identification and analysis system. Drug Saf. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S83–93.

Noren GN, Bergvall T, Ryan PB, et al. Empirical performance of the calibrated self-controlled cohort analysis within temporal pattern discovery: lessons for developing a risk identification and analysis system. Drug Saf. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S107–21.

Ryan PB, Schuemie MJ, Welebob E, et al. Defining a reference set to support methodological research in drug safety. Drug Saf. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S33–47.

Ryan PB, Madigan D, Stang PE, et al. Empirical assessment of methods for risk identification in healthcare data: results from the experiments of the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership. Stat Med. 2012;31(30):4401–15.

Lewis JD, Schinnar R, Bilker WB, et al. Validation studies of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database for pharmacoepidemiology research. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:393–401.

Lin NC, Norman H, Regev A, et al. Hepatic outcomes among adults taking duloxetine: a retrospective cohort study in a US health care claims database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:134.

Richards JB, Papaioannou A, Adachi JD, et al. Effect of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on the risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):188–94.

Wu Q, Bencaz AF, Hentz JG, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of cohort and case–control studies. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:365–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1778-8.

Liu B, Anderson G, Mittmann N, et al. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors or tricyclic antidepressants and risk of hip fractures in elderly people. Lancet. 1998;351:1303–7.

Hubbard R, Farrington P, Smith C, et al. Exposure to tricyclic and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and the risk of hip fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(1):77–84.

Hua W, Sun G, Dodd CN, et al. A simulation study to compare three self-controlled case series approaches: correction for violation of assumption and explanation of bias. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:819–25.

Hauben M, Reich L. Safety related drug-labelling changes: findings from two data mining algorithms. Drug Saf. 2004;27(10):735–44 (published erratum appears in Drug Saf 2006;29(12):1191).

Hochberg AM, Hauben M, Pearson RK, et al. An evaluation of three signal-detection algorithms using a highly inclusive reference event database. Drug Saf. 2009;32(6):509–25.

Foundation for National Institutes of Health, OMOP. Observational analysis methods and methods library. http://omop.org/MethodsLibrary. Accessed 6 Nov 2013.

Gruber S, Chakravarty A, Heckbert SR, et al. Design and analysis choices for safety surveillance evaluations need to be tuned to the specifics of the hypothesized drug–outcome association. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25:973–81.

Lewis J, Bilker WB, Weinstein RB, et al. The relationship between time since registration and measured incidence rates in the General Practice Research Database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:443–51.

Traczewski P, Rudnicka L. Adalimumab in dermatology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(5):618–25.

Humira (adalimumab) label. FDA, 2011. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/125057s0276lbl.pdf. Accessed 3 Dec 2017.

Ryan P. Highlights from the Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership’s (OMOP) annual symposium. Brookings roundtable on active medical product surveillance, 8 Aug 2012. http://omop.org. Accessed 25 Oct 2016.

Ryan P, Schuemie MA, Madigan D. Learning from epidemiology: interpreting observational database studies for the effects of medical products. Stat Biopharm Res. 2013;5(3):170–9.

Falck-Ytter Y, Guyatt GH. Chapter 3: Guidelines: Rating the Quality of Evidence and Grading the Strength of Recommendations. In: Burneo J, Demaerschalk B, Jenkins M (eds), Neurology. New York: Springer; 2012

Douglas IJ, Smeeth L. Exposure to antipsychotics and risk of stroke: self-controlled case series study. BMJ. 2008;28(337):a1227.

Humira (adalimumab) label. FDA, 2002. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2002/adalabb123102LB.htm. Accessed 5 Nov 2017.

Strangfeld A, Listing J, Herzer P, et al. Risk of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF alpha agents. JAMA. 2009;301(7):737e44.

Hopstadius J, Noren GN, Bate A, et al. Impact of stratification in adverse drug reaction surveillance. Drug Saf. 2008;31(11):1035–48.

Gagne JJ, Nelson JC, Fireman B. Taxonomy for monitoring methods within a medical product safety surveillance system: year two report of the Mini-Sentinel Taxonomy Project Workgroup. https://www.sentinelinitiative.org/sites/default/files/Drugs/Assessments/Mini-Sentinel_Methods_Taxonomy-Year-2-Report.pdf. Accessed 5 may 2017.

Waller P, Heeley E, Moseley J. Impact analysis of signals detected from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting data. Drug Saf. 2005;28(10):843–50.

Waller PC, Lee EH. Responding to drug safety issues. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1999;8:535–552

Lindquist M, Edwards IR, Bate A, et al. From association to alert—a revised approach to international signal analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 1999;8(Suppl 1):S15–25.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge OMOP for the open source code that provided the basis for the SCCS implementation code used for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Conflicts of interest

Xiaofeng Zhou, Rongjun Shen, and Andrew Bate are full-time employees of Pfizer Inc. and hold stock and stock options. Pfizer manufactures one of the drugs studied herein, desvenlafaxine, as well as other products used to treat primary indications of the other two drugs analyzed herein, namely depression and rheumatoid arthritis. Ian Douglas is a full-time employee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and received no funding from Pfizer for his contribution to this study and article. He is funded by an unrestricted grant from, holds stock in, and has consulted for, GlaxoSmithKline.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, X., Douglas, I.J., Shen, R. et al. Signal Detection for Recently Approved Products: Adapting and Evaluating Self-Controlled Case Series Method Using a US Claims and UK Electronic Medical Records Database. Drug Saf 41, 523–536 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0626-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0626-y