Abstract

Introduction and Aims

The DIPAK-1 Study investigates the reno- and hepatoprotective efficacy of the somatostatin analog lanreotide compared with standard care in patients with later stage autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). During this trial, we witnessed several episodes of hepatic cyst infection, all during lanreotide treatment. We describe these events and provide a review of the literature.

Methods

The DIPAK-1 Study is an ongoing investigator-driven, randomized, controlled, open-label multicenter trial. Patients (ADPKD, ages 18–60 years, estimated glomerular filtration rate 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2) were randomized 1:1 to receive lanreotide 120 mg subcutaneously every 28 days or standard care during 120 weeks. Hepatic cyst infection was diagnosed by local physicians.

Results

We included 309 ADPKD patients of which seven (median age 53 years [interquartile range: 48–55], 71% female, median estimated glomerular filtration rate 42 mL/min/1.73 m2 [interquartile range: 41–58]) developed eight episodes of hepatic cyst infection during 342 patient-years of lanreotide use (0.23 cases per 10 patient-years). These events were limited to patients receiving lanreotide (p < 0.001 vs. standard care). Baseline characteristics were similar between subjects who did or did not develop a hepatic cyst infection during lanreotide use, except for a history of hepatic cyst infection (29 vs. 0.7%, p < 0.001). Previous studies with somatostatin analogs reported cyst infections, but did not identify a causal relationship.

Conclusions

These data suggest an increased risk for hepatic cyst infection during use of somatostatin analogs, especially in ADPKD patients with a history of hepatic cyst infection. The main results are still awaited to fully appreciate the risk–benefit ratio.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

NCT 01616927.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Increased risk for hepatic cyst infection during use of lanreotide has been observed in the ongoing DIPAK-1 Study. |

A literature review also suggested an increased risk for hepatic cyst infection during use of somatostatin analogs. |

A history of hepatic cyst infection may be a factor that predisposes for a novel cyst infection. |

If a hepatic cyst infection develops, stopping somatostatin analog treatment should be considered, based on an assessment of the potential benefit of the drug vs. the possible increased risk for recurrent cyst infection. |

1 Introduction

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is a hereditary progressive disorder characterized by the formation and growth of renal and hepatic cysts. In most of the affected patients, progressive renal function loss leads to end-stage renal disease. In general, there is a need for renal replacement therapy between the fourth and sixth decade of life [1]. At the age of 35 years, more than 90% of ADPKD patients have one or more hepatic cysts [2]. Polycystic liver disease (PLD) is defined as the presence of ≥20 hepatic cysts [3]. Hepatic cysts can also occur sporadically in the absence of a renal cystic phenotype in ~10% of the population [4]. Patients with PLD in whom ADPKD is ruled out are referred to as autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease (ADPLD) [5]. In general hepatic cysts do not affect liver function [6]. The increase in total kidney volume (TKV) and total liver volume (TLV) can be severe and lead to intra-abdominal mass-related complaints, such as abdominal discomfort, pain, and early satiety, which negatively impact quality of life [7, 8].

Previous small-scale studies suggested that somatostatin analogs have the potential to slow the rate of kidney function decline and cyst growth by 50% [9]. The ongoing DIPAK-1 Study is designed to establish the efficacy of the somatostatin analog lanreotide, to preserve kidney function in later stage ADPKD, affecting quality of life and life span [10]. Known side effects of somatostatin analogs are transient gastrointestinal complaints, such as diarrhea and abdominal cramps. There is no evidence suggesting that these drugs increase the risk for infections [11]. However, during the DIPAK-1 Study, eight episodes of hepatic cyst infection developed in seven patients taking lanreotide, whereas in the control group no such events occurred. Although hepatic cyst infections have been reported in several trials that investigated somatostatin analogs [12, 13], these events have not been causally linked to this class of drugs.

In this report, we describe the ADPKD patients enrolled in the DIPAK-1 Study who were diagnosed with a hepatic cyst infection. We investigate factors that might contribute to these infections and provide a systematic review of literature on the occurrence of hepatic cyst infections in other trials with somatostatin analogs in ADPKD and PLD.

2 Methods

2.1 Study Population and Design

The DIPAK-1 Study is an investigator-driven, randomized, controlled, open-label, multicenter trial of patients ages 18–60 years with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 30–60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Patients were enrolled at four University Medical Centers in the Netherlands (Groningen, Leiden, Nijmegen, and Rotterdam) between June 2012 and March 2015. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive standard care (control group) or subcutaneous lanreotide injections (120 mg, Somatuline; Ipsen, Boulogne Billancourt, France), every 28 days for 120 weeks, in addition to standard care (intervention group). Lanreotide was administered by trained nurses from an independent home service as part of routine clinical care. The patient or nurse received the medication from the local pharmacy. The lanreotide was stored at home until administration in a refrigerator between 2 and 8 °C.

The trial design is described in detail elsewhere (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT 01616927). The DIPAK-1 Study is conducted in accordance with the International Conference of Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines and the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the University Medical Center Groningen (METc 2012/060), that acted as the central IRB, and by the IRBs at each trial site. All patients provided written informed consent.

2.2 Patients with Hepatic Cyst Infection

We performed an interim analysis of the ongoing DIPAK-1 Study using data until 28 January, 2016. At the time of analysis, all patients were randomized and enrolled for at least 10 months. Our interim analysis describes the eight episodes of hepatic cyst infection in seven patients (cases). This diagnosis was made by the treating physicians based on clinical symptoms and additional investigations [14]. These physicians provided detailed information on clinical, biochemical, microbiological, and imaging results. A body temperature >38 °C was considered as fever. Baseline characteristics were extracted from the DIPAK-1 Study database, which allowed a direct comparison between patients taking lanreotide, with and without hepatic cyst infection. Specifically, the following patient and disease characteristics were extracted: demographics, study arm, body mass index, laboratory results at baseline and, if applicable, at presentation of cyst infection, DNA mutation analysis, magnetic resonance imaging (including TLV and TKV), history of hepatic and/or renal cyst infection, and history of urinary tract infection. We used center-specific cutoff-values for laboratory values to identify abnormal results.

2.3 Literature Review

To investigate the incidence of hepatic cyst infections in ADPKD and PLD patients in other clinical studies with somatostatin analogs, we systematically searched the electronic database of PubMed on 19 January, 2016 using the following query: [somatostatin AND (ADPKD OR polycystic kidney disease OR PLD OR polycystic liver disease)].

2.4 Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to summarize demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of patients. Continuous variables are expressed as mean with standard deviation or as median with interquartile range, as appropriate. The Chi-square test and Student t test for parametric data and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric data were used to compare baseline characteristics between hepatic cyst infection cases and the remainder of patients randomized to lanreotide treatment. All tests were two-tailed and a p value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significant differences. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 (SPSS Statistics, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Patients with Cyst Infection

Seven of 309 patients (2%) developed a total of eight hepatic cyst infection episodes. These cases are described below and clinical details are summarized in Table 1. Importantly, in all cases the diagnosis of hepatic cyst infection was made by local physicians, which were not part of the study team.

3.1.1 Case 1 (Episode 1 and 2)

A 46-year old man with ADPKD and PLD (Fig. 1) presented with fever (38.7 °C) and complained of acute right upper-quadrant abdominal pain and mild diarrhea (Table 1). Lanreotide treatment (120 mg) was started 3 months earlier (Fig. 2). At admission, laboratory investigations showed a grossly elevated serum C-reactive protein (CRP, 584 mg/L). Urine sediment examination showed no leukocyturia. Chest radiograph, abdominal ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging were unremarkable. Local physicians initiated intravenous antibiotic treatment with three times-daily cefuroxim/metronidazole plus gentamicin bolus injections. The urine culture was negative, but blood cultures grew Escherichia coli. Treatment was switched to oral ciprofloxacin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. 18Fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) was performed at day 8 after admission to locate the infection source, which revealed two hepatic cysts showing signs of infection (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Because of persisting fever, the hepatic cysts were drained in two sessions at day 9. Cyst aspirations did not cause any complications. Both cysts contained pus, but cultures remained negative. After 30 days, the patient was discharged and ciprofloxacin monotherapy was continued for another 4 weeks. Recovery was uneventful. Lanreotide treatment was continued.

Baseline T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of patients developing hepatic cyst infection during the DIPAK-1 Study. Height-adjusted liver volume (hTLV) were 2670, 1579, 823, 2723, 8635, 1901, and 997 mL/m in respectively, cases 1–7 (a–f). In five of seven patients, the phenotype consists of multiple small- and medium-sized cysts spread throughout the liver, with remaining large areas of non-cystic liver parenchyma [cases 1–4 (a–d) and 6 (f)]. One patient [case 5 (e)] showed a phenotype with massive diffuse involvement of liver parenchyma by small- and medium-sized liver cysts, with only a few areas of remaining normal liver parenchyma between cysts. Remarkably, the liver phenotype of the last patient who developed a hepatic cyst infection was limited to a single hepatic cyst [case 7 (g)]

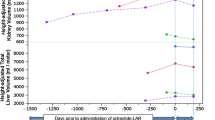

Reverse Kaplan–Meier curve showing time to development of a first hepatic cyst infection in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease patients participating in the lanreotide and control groups of the ongoing DIPAK-1 Study (interim analysis). The median time patients had received lanreotide until onset of hepatic cyst infection was 4 months (interquartile range 2–5 months)

However, 4 months after stopping antibiotic treatment, this patient again experienced acute abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant and fever (38.9 °C). Laboratory results showed an increased serum CRP (190 mg/L) and urinalysis excluded leukocyturia. No liver enzyme data were available during this second episode. One month after the diagnosis of the second liver cyst infection episode, Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) were increased (respectively, 97 and 144), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging could not locate the source of infection, and urine and blood cultures were negative. The working diagnosis was recurrent hepatic cyst infection and local physicians started intravenous ceftriaxone treatment, which was switched to oral ciprofloxacin 5 days later. After 6 days, the patient was discharged, and ciprofloxacin was continued for another 15 days. Final recovery was without sequelae. One month after the diagnosis of the second liver cyst infection episode, ALP and GGT were increased (respectively, 97 and 144), as AST and ALT were normal.

3.1.2 Case 2

A 51-year-old woman with ADPKD and PLD (Fig. 1) presented at the hospital because of right upper-quadrant abdominal pain, fever (38 °C), nausea, and vomiting. Lanreotide treatment (120 mg) was started 5 months earlier. At admission, serum CRP was 329 mg/L and serum liver enzymes were normal (AST 29 U/L, ALT 27 U/L, ALP 57 U/L, and GGT 39 U/L). Local physicians initiated piperacillin/tazobactam intravenously under the suspicion of hepatic cyst infection. Blood cultures grew E. coli. Abdominal CT at admission showed no sign of hepatic cyst infection. Patient was hospitalized for 3 days. Treatment was switched to ciprofloxacin twice daily at discharge and continued for 2 weeks. 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed 3 days after discharge and revealed two hepatic cysts showing signs of infection. Recovery was uneventful.

3.1.3 Case 3

A 54-year-old woman with ADPKD and PLD (Fig. 1) presented with fever (39.6 °C) and cold shivers without abdominal pain, after having experienced abdominal complaints during a few weeks following each lanreotide injection. Lanreotide treatment (120 mg) was started 5 months earlier. At admission, serum CRP was 245 mg/L and some liver enzymes were elevated (ALT 62 U/L, ALP 119 U/L, and GGT 83 U/L). Leukocyturia was excluded with urine sediment analysis. Abdominal ultrasound showed no abnormalities, except for gallbladder sludge. Blood cultures grew E. coli. The patient was hospitalized for 3 days and treated by local physicians under the suspicion of hepatic cyst infection with cefuroxime intravenously. At discharge, treatment was switched to ciprofloxacin for another 11 days. Recovery was uneventful.

3.1.4 Case 4

A 55-year-old woman with ADPKD and PLD (Fig. 1) and a history of a hepatic cyst infection (6 months and 1 year prior to the current event) developed fever (38.9 °C) and right upper-quadrant abdominal pain during a stay abroad. Lanreotide treatment (120 mg) was started 2 months earlier. She was hospitalized in a foreign country. At admission, serum CRP and liver enzymes were not determined, but serum white blood cell count was 9.0 × 10e9/L. Liver enzymes on day 4 after admission were not raised (AST 17 U/L, ALT 19 U/L, ALP 52 U/L, and GGT 39 U/L). A chest radiograph and abdominal ultrasound (performed on the day of admission and 1 day after, respectively) were unremarkable. A chest radiograph was repeated on the second day of admission and showed right-sided abnormalities compatible with either atelectasis or pneumonia. In contrast, 18F-FDG PET/CT (performed 3 days after admission) was unremarkable. All blood cultures were negative. Under the suspicion of hepatic cyst infection, the patient was hospitalized for 4 days and treated by local physicians with intravenous ampicillin-tazobactam, vancomycin, and meropenem. This was followed by oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for a total of 90 days. Recovery was uneventful.

3.1.5 Case 5

A 56-year-old woman with ADPKD and PLD (Fig. 1) and a history of hepatic cyst infection developed right lower-quadrant abdominal pain and experienced a loss of appetite. The patient had no fever. Lanreotide injections (120 mg) were started 3 months earlier. At admission, laboratory investigations revealed increased serum CRP (156 mg/L) and increased serum ALP and GGT (123 U/L and 106 U/L, respectively). Urine sediment analysis revealed leukocyturia. Under the diagnosis of hepatic cyst infection, the patient was treated with cefuroxim/metronidazole intravenously for 1 day. Blood and urine cultures remained negative. 18F-FDG PET/CT (performed 4 days after admission) showed signs of a hepatic cyst infection (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Treatment was switched to oral ciprofloxacin for another 80 days. After 3 days, the patient was discharged. Recovery was uneventful.

3.1.6 Case 6

A 49-year-old woman with ADPKD and PLD (Fig. 1) was referred to the hospital because of upper abdominal pain, fever (38.3 °C) with cold shivers and diarrhea. Lanreotide injections (120 mg) were started 2 months earlier. Because of complaints of bradycardia and hypotension, the lanreotide dose was adjusted to 90 mg after the first injection. At admission, serum CRP was 105 mg/L, with elevated ALP (150 U/L) and GGT (230 U/L). Urine sediment analysis revealed leukocyturia. During admission, a chest radiograph and abdominal ultrasound did not show abnormalities, whereas a magnetic resonance imaging scan showed an image of renal cyst hemorrhage in both kidneys. Under the suspicion of hepatic cyst infection, the patient was treated with oral ciprofloxacin. Urine and blood cultures remained negative. Hospitalisation lasted 5 days, and in total ciprofloxacin was given during 42 days. Recovery was uneventful.

3.1.7 Case 7

A 57-year-old man with ADPKD and a limited number of hepatic cysts (Fig. 1) was admitted to the hospital because of fever (39.8 °C), right-sided flank pain, diarrhea, vomiting, and headache. Lanreotide injections (120 mg) were started 19 months earlier. At admission, serum CRP was elevated (131 mg/L) and liver enzymes were not elevated (AST 23 U/L, ALT 22 U/L, ALP 71 U/L, GGT 35 U/L). Leukocyturia was excluded. A chest radiograph and abdominal ultrasound were unremarkable. Blood cultures grew E. coli, whereas urine cultures were negative. Under the suspicion of hepatic cyst infection, the patient was hospitalized and treatment with ceftriaxone intravenously was initiated by the local physicians. At discharge, after 3 days, treatment was switched to oral ciprofloxacin for a total of 7 weeks. Recovery was uneventful.

The time between injection and development of cyst infection differed widely between patients (1–21 days). The number of days between injection and cyst infection for the individual cases was: 16 (case 1 episode 1) 21 (case 1 episode 2), 8 (case 2), 9 (case 3), 8 (case 4), 16 (case 5), 11 (case 6), and 1 (case 7). It was not documented whether microbiologists were involved in the management of liver cyst infections and whether antibiotic susceptibilities were performed.

3.2 Baseline Characteristics of Patients Receiving Lanreotide

All seven patients that were diagnosed with a hepatic cyst infection were receiving lanreotide treatment. Baseline characteristics as listed in Table 2 were not different between patients randomized to lanreotide or control treatment (data not shown). Therefore, Table 2 provides the baseline characteristics of only patients treated with lanreotide, stratified for cases with (n = 7) and without hepatic cyst infection during follow-up (n = 147). A history of hepatic cyst infection was present in 29% (n = 2 of 7) of cyst infection cases, compared with 0.7% (n = 1 of 147) in non-affected patients (p < 0.001). Of note, case 1 had two disease episodes diagnosed as hepatic cyst infection, and the second episode can therefore be regarded as having occurred in a patient with a history of hepatic cyst infection. Following this line of thinking, a history of hepatic cyst infection was present in 43% (n = 3 of 7) of cyst infection cases. At baseline, sex and age were comparable between cases and non-affected patients (p = 0.32 and p = 0.24, respectively), as was eGFR, height-adjusted liver volume (hTLV), and height-adjusted kidney volume (hTKV) (p = 0.97, p = 0.17, and p = 0.57, respectively). At the time the data for this report were extracted (28 January, 2016), the total duration of treatment with lanreotide was 342 patient-years, indicating an incidence of hepatic cyst infections of 0.23 per 10 patient-years (eight episodes of hepatic cyst infection).

3.3 Literature Review

We identified 13 clinical studies assessing the effect of somatostatin analogs (lanreotide or octreotide) in ADPKD or PLD patients between 2005 and 2015 (Table 3). One study was excluded as this was a post hoc analysis of a clinical trial that is also included [15]. Of the 12 included studies [9, 12, 13, 16–24], four studies involved randomized placebo-controlled trials [9, 16–18], whereas eight studies were observational and lacked a control group [12, 13, 19–24]. A total of 455 patients were included (ADPKD n = 363; ADPLD n = 92), of whom 375 were treated with somatostatin analogs. Duration of study treatment varied between 6 months and 3 years. In seven trials, intramuscular octreotide-long-acting release (LAR) 40 mg every 28 days was used, and in five trials, subcutaneous lanreotide 120 mg was used every 28 days. Total duration of treatment with somatostatin analogs in these nine studies was 434 patient-years, compared with 151 patient-years with placebo or control treatment.

Four studies (all observational, none controlled) mentioned a total of six cyst infection cases. All cases occurred in patients receiving somatostatin analogs [12, 13, 20, 22]. In three patients, a hepatic cyst infection was diagnosed, [12, 13, 22] while in the remaining three patients it was not specifically stated whether a hepatic or renal cyst infection developed [13, 20]. None of these events were deemed related to study drug by the authors of the original articles. In the case of all events being hepatic cyst infection episodes, the incidence rate would be 0.09 per 10 patient-years during use of somatostatin analogs. In addition, two studies mentioned two cases with fever of unknown origin, both patients randomized to octreotide treatment [18, 20]. In one case, an infectious cause was ruled out and the patient recovered after discontinuing the study drug, [20]. whereas the other responded to antibiotic treatment [18].

4 Discussion

In the DIPAK-1 Study, seven patients on the somatostatin analog lanreotide experienced a hepatic cyst infection, whereas no hepatic cyst infection was seen in the standard care group. In other studies with somatostatin analogs, potentially six hepatic cyst infections were identified, whereas no such events were observed in patients in the control or placebo groups.

Hepatic cyst infection is a potential complication of ADPKD that can be serious, and in nearly all cases leads to hospitalization [25]. Diagnosing cyst infection represents a challenge [26]. The cases described in this paper did not show any prodromi that could be considered as early symptoms of liver cyst infection. In three of seven cases, diarrhea was reported but stools were not tested for steatorrhea. Diarrhea is a very common side effect of lanreotide treatment. It has been described in 81% of patients in a recent trial [13]. In none of the affected cases, stool cultures were performed.

In the case of abdominal pain and increased CRP, hepatic cyst infection should be included in the differential diagnosis. The proposed gold standard for diagnosing a hepatic cyst infection is a cyst aspirate containing white blood cells and pathogens. However, in clinical care, cyst aspiration is only rarely performed as a large group of cyst infections are caused by E. coli and most patients respond well to antibiotics. Therefore, blood cultures were not repeated after an episode of cyst infection. Blood and urine should be cultured when symptoms arise and an 18F-FDG PET/CT can be of diagnostic help. Antibiotic treatment should be given for several weeks guided by CRP levels, though there is no consensus about treatment duration. Some cases (case 4 and 5) received very long treatment with antibiotics (90 and 81 days), probably as both patients had a history of liver infection and the chance for recurrence was high. Therefore, physicians sometimes choose to treat patient for 1–2 months, although this is not evidence based. First-line treatment with oral ciprofloxacin is recommended, in the case of failure, percutaneous cyst drainage can be considered.

A systematic review of the literature on hepatic cyst infections showed that the treatment of hepatic cyst infection is highly heterogeneous [27]. In the literature, there is no agreement on how to define ‘treatment success’. C-reactive protein is a potential biomarker for the evaluation of infection activity; however, in our own clinical experience, persisting elevated levels of CRP are seen in the case of hepatic cyst infection [28]. In the eight disease episodes that are described in this report, all hepatic cyst infection cases were diagnosed by local physicians as customary on clinical manifestations, in the absence of a positive cyst aspirate, but with positive 18F-FDG PET/CT scans in three patients. In some cases, the Principal Investigator was involved in the treatment of the liver cyst infection as the PI has clinical experience treating these patients. No patient developed tenosynovitis after treatment with ciprofloxacin.

The exact incidence rate of cyst infections in ADPKD is unclear. Only one study reported an incidence rate of 8.4% (33 of 389 patients) renal and/or hepatic cyst infection in ADPKD patients [25]. The challenge is to differentiate the clinical picture of hepatic cyst infection with other more common causes of fever, increased inflammatory markers, and abdominal pain. Caroli syndrome is characterized by congenital cystic dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary tree and therefore not directly comparable with PLD in ADPKD, in which the liver cysts remain separated from the biliary tract. As a consequence of dilatation of the biliary tree, cholangitis is a major problem in these patients [25].

After the fifth report of hepatic cyst infection, the steering committee and the data safety monitoring board decided to ask for an interim analysis to assess the risk of hepatic cyst infection with lanreotide. In retrospect, we deem the diagnosis of hepatic cyst infection highly likely in three episodes (case 1 first event, and cases 2 and 5), likely in three episodes (case 1 s event, and cases 3 and 7), and possible in two episodes (cases 4 and 6), because in these latter two cases alternative diagnoses may be considered (pneumonia and cyst hemorrhage, respectively). In accordance with good clinical practice, however, the diagnosis as judged by the reporting healthcare professional was adopted in all cases. We found that baseline liver volume, kidney volume, age, sex, history of renal cyst infection or urinary tract infection, and serum liver and kidney parameters were not different between patients receiving lanreotide who developed a hepatic cyst infection and those that did not. This observation is in line with a recent study of 461 ADPKD patients that failed to detect a relationship between patient characteristics and infectious complications [29]. The only difference we found was that lanreotide-treated patients who developed a hepatic cyst infection more often had a history of cyst infection when compared with lanreotide-treated patients who did not experience such an event.

A literature search revealed that in other studies investigating somatostatin analogs in ADPKD and PLD, including ADPLD, cyst infections occurred in six subjects receiving active treatment [12, 13, 20, 22]. In three of six cases, no clear differentiation could be made between hepatic or renal cyst infections [13, 20]. Even when all cases were assigned as hepatic cyst infections, the estimated incidence rate in these studies was considerably lower than in our study (0.09 vs. 0.23 per 10 patient-years). These small-scale studies did not identify a causal relationship between cyst infection and use of somatostatin analogs, but this may be owing to the fact that these studies included relatively small numbers of patients, often lacked a control group, and that hepatic cyst infection has a low incidence.

After evaluation, it was decided that the trial could continue because all patients who developed a cyst infection recovered after antibiotic treatment without sequelae, and because lanreotide might induce a favorable effect on rate of disease progression. At that moment (6 August, 2013), almost half of the 154 patients who would ultimately receive lanreotide had already entered the DIPAK-1 Study. For safety reasons, however, it was decided to stop treatment in patients who developed a hepatic cyst infection, and to add a history of hepatic cyst infection to the exclusion criteria. Because of this latter exclusion criterion, lanreotide treatment was withdrawn in one patient. In addition, the patient’s informed consent form was amended to provide information on this potential adverse event. The central IRB agreed with this line of reasoning. Thereafter, only three additional cases were noted until 28 January, 2016.

From the present data, it is unclear which mechanism underlies the increased incidence of hepatic cyst infection during lanreotide use. Liver cysts in ADPKD arise as a result of ductal plate malformation in the embryonic development, which leads to large dilated segments of the primitive bile duct with concomitant abnormal fluid secretion [6]. It might be possible that bacterial translocation from the intestinal wall to the liver cysts is involved in the occurrence of cyst infections; however, research supporting this theory is lacking [30]. In our cases with a positive culture, liver infections were caused by E. coli, a species that is present in the gut in large numbers. Escherichia coli translocates very efficiently, even across the histologically intact intestinal epithelium, possibly owing to a greater ability to adhere to the intestinal mucosa [31]. Bacterial translocation from the gut to the liver might be promoted by a reduction in blood flow in the superior mesenteric artery and portal vein, which is a known effect of somatostatin analogs [31–33]. Another effect of somatostatin analogs is a reduction in gallbladder contractility. This leads to reduced bile flow, which might promote bacterial translocation via the biliary tract. Another potential mechanism could be that lanreotide affects the gut immune system by reducing antimicrobial peptides and proteins located at the epithelium [32].

A potential limitation of the present analysis is that this is a retrospective interim analysis and that hepatic cyst infections were not diagnosed centrally but in clinical centers by local physicians. However, these physicians were not part of the study team, and were not aware of each other’s findings, implying that investigator bias is unlikely. The main strength is that it reports on the largest study with a somatostatin analog for the indication to slow disease progression in ADPKD. The large sample size allows a better estimate of the safety profile of this drug class, including rare idiosyncratic drug reactions.

In clinical care, somatostatin analogs are used off label to treat ADPKD and PLD patients’ mass-related complaints as a result of cystic liver disease. The increased incidence of hepatic cyst infection during use of lanreotide might be drug related, but may also reflect a class effect, as suggested by the findings of our systematic literature search that described incidental cases of hepatic cyst infection during treatment with other somatostatin analogs. Based on our experience, we advise physicians to be cautious when prescribing somatostatin analogs to ADPKD and ADPLD patients with a history of hepatic cyst infection and that patients should be informed about this potential risk. In the case of the development of a hepatic cyst infection, stopping somatostatin analog treatment should be considered, based on an assessment of the potential benefit of the drug vs. the possible increased risk for recurrent cyst infection.

5 Conclusion

During the ongoing DIPAK-1 Study, several cases of hepatic cyst infection developed in ADPKD patients in the lanreotide group whereas this was not the case in the standard care group. A history of hepatic cyst infection may be a factor that predisposes for a novel cyst infection. A literature review also suggested an increased risk for hepatic cyst infection during the use of somatostatin analogs. The main results of the DIPAK-1 Study are still awaited to fully appreciate the risk–benefit ratio of somatostatin analogs in ADPKD patients.

References

Torres VE, Harris PC, Pirson Y. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1287–301.

Bae KT, Zhu F, Chapman AB, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of hepatic cysts in early autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: the Consortium for Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(1):64–9.

Van Keimpema L, De Koning DB, Van Hoek B, et al. Patients with isolated polycystic liver disease referred to liver centres: clinical characterization of 137 cases. Liver Int. 2011;31(1):92–8.

Larssen TB, Rørvik J, Hoff SR, et al. The occurrence of asymptomatic and symptomatic simple hepatic cysts: a prospective, hospital-based study. Clin Radiol. 2005;60(9):1026–9.

Cnossen WR, Drenth JP. Polycystic liver disease: an overview of pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:69.

Gevers TJ, Drenth JP. Diagnosis and management of polycystic liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10(2):101–8.

Wijnands TF, Neijenhuis MK, Kievit W, et al. Evaluating health-related quality of life in patients with polycystic liver disease and determining the impact of symptoms and liver volume. Liver Int. 2014;34(10):1578–83.

Miskulin DC, Abebe KZ, Chapman AB, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and CKD stages 1-4: a cross-sectional study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(2):214–26.

Caroli A, Perico N, Perna A, et al. Effect of longacting somatostatin analogue on kidney and cyst growth in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ALADIN): a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1485–95.

Meijer E, Drenth JP, d'Agnolo H, et al. Rationale and design of the DIPAK 1 study: a randomized controlled clinical trial assessing the efficacy of lanreotide to halt disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(3):446–55.

Fleseriu M. Clinical efficacy and safety results for dose escalation of somatostatin receptor ligands in patients with acromegaly: a literature review. Pituitary. 2011;14(2):184–93.

Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page L, et al. Somatostatin analog therapy for severe polycystic liver disease: results after 2 years. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(9):3532–9.

Gevers TJ, Hol JC, Monshouwer R, et al. Effect of lanreotide on polycystic liver and kidneys in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: an observational trial. Liver Int. 2015;35(5):1607–14.

Lantinga MA, Drenth JP, Gevers TJ. Diagnostic criteria in renal and hepatic cyst infection. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;30(5):744–51.

Caroli A, Antiga L, Cafaro M, et al. Reducing polycystic liver volume in ADPKD: effects of somatostatin analogue octreotide. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(5):783–9.

Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi A, Ondei P, et al. Safety and efficacy of long-acting somatostatin treatment in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68(1):206–16.

van Keimpema L, Nevens F, Vanslembrouck R, et al. Lanreotide reduces the volume of polycystic liver: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1661–8 e1–2.

Hogan MC, Masyuk TV, Page LJ, et al. Randomized clinical trial of long-acting somatostatin for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney and liver disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(6):1052–61.

Chrispijn M, Nevens F, Gevers TJ, et al. The long-term outcome of patients with polycystic liver disease treated with lanreotide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(2):266–74.

Chrispijn M, Gevers TJ, Hol JC, et al. Everolimus does not further reduce polycystic liver volume when added to long acting octreotide: results from a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):153–9.

Higashihara E, Nutahara K, Okegawa T, et al. Safety study of somatostatin analogue octreotide for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in Japan. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19(4):746–52.

Hogan MC, Masyuk T, Bergstralh E, et al. Efficacy of 4 years of octreotide long-acting release therapy in patients with severe polycystic liver disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(8):1030–7.

Temmerman F, Ho TA, Vanslembrouck R, et al. Lanreotide reduces liver volume, but might not improve muscle wasting or weight loss, in patients with symptomatic polycystic liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(13):2353–9 e1.

Treille S, Bailly JM, Van Cauter J, et al. The use of lanreotide in polycystic kidney disease: a single-centre experience. Case Rep Nephrol Urol. 2014;4(1):18–24.

Sallée M, Rafat C, Zahar JR, et al. Cyst infections in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(7):1183–9.

Lantinga MA, Drenth JP, Gevers TJ. Diagnostic criteria in renal and hepatic cyst infection. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(5):744–51.

Lantinga MA, Geudens A, Gevers TJ, et al. Systematic review: the management of hepatic cyst infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(3):253–61.

Lantinga MA, de Sevaux RG, Drenth JP. 18F-FDG PET/CT during diagnosis and follow-up of recurrent hepatic cyst infection in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2015;84(1):61–4.

Kim H, Park HC, Ryu H, et al. Clinical correlates of mass effect in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144526.

Suwabe T, Araoka H, Ubara Y, et al. Cyst infection in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: causative microorganisms and susceptibility to lipid-soluble antibiotics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34(7):1369–79.

Wiest R, Garcia-Tsao G. Bacterial translocation (BT) in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2005;41(3):422–33.

O’Donnell LJ, Farthing MJ. Therapeutic potential of a long acting somatostatin analogue in gastrointestinal diseases. Gut. 1989;30(9):1165–72.

Parks DA, Jacobson ED. Physiology of the splanchnic circulation. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145(7):1278–81.

Acknowledgements

DIPAK Consortium The DIPAK Consortium is an inter-university collaboration in the Netherlands that is established to study autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and to develop rational treatment strategies for this disease. Principal investigators are (in alphabetical order): J. P. H. Drenth (Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen), J. W. de Fijter (Department of Nephrology, Leiden University Medical Center), R. T. Gansevoort (Department of Nephrology, University Medical Center Groningen), D. J. M. Peters (Department of Human Genetics, Leiden University Medical Center), J. Wetzels (Department of Nephrology, Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen), and R. Zietse (Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam). Data Safety Monitoring Board Per-protocol patient safety in the DIPAK-1 Study is assessed by an independent data safety monitoring board. Members are (in alphabetical order): M. van Buren (Department of Internal Medicine and Nephrology, Haga Hospital, The Hague), C. A. J. M. Gaillard (Department of Nephrology, University Medical Center Groningen), N. J. G. M. Veeger (Department of Epidemiology, University Medical Center Groningen and Medical Center Leeuwarden), and M. G. Vervloet (Chair, Department of Nephrology, Free University Medical Center, Amsterdam).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The DIPAK-1 study is made possible by a grant from the Dutch Kidney Foundation (CP10.12), with Ipsen Farmaceutica B.V., the Netherlands acting as a minor co-sponsor. The Dutch Kidney Foundation and Ipsen had no role in the design or conduct of the study, or in the writing and submission of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Marten A. Lantinga, Hedwig M.A. D’Agnolo, Niek F. Casteleijn, Johan W. de Fijter, Esther Meijer, Annemarie L. Messchendorp, Dorien J.M. Peters, Mahdi Salih, Darius Soonawala, Folkert W. Visser, and Jack F.M. Wetzels have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study. Edwin M. Spithoven has received payment for an Otsuka presentation about the epidemiology of ADPKD and future perspectives. Robert Zietse has received previous grant support from Ipsen. Joost P.H. Drenth has received previous grant support from Ipsen and Novartis. Ron T. Gansevoort holds the rights on the Orphan Designation status of lanreotide for the indication ADPKD, which was granted by the European Medicines Agency (EU/3/15/1514).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

M. A. Lantinga and H. M. A. D’Agnolo contributed equally to the article.

The members of DIPAK Consortium are listed in “Acknowledgements”.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lantinga, M.A., D’Agnolo, H.M.A., Casteleijn, N.F. et al. Hepatic Cyst Infection During Use of the Somatostatin Analog Lanreotide in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease: An Interim Analysis of the Randomized Open-Label Multicenter DIPAK-1 Study. Drug Saf 40, 153–167 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0486-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0486-x