Abstract

Introduction

Interest in the use of psychedelic substances for the treatment of mental disorders is increasing. Processes that may affect therapeutic change are not yet fully understood. Qualitative research methods are increasingly used to examine patient accounts; however, currently, no systematic review exists that synthesizes these findings in relation to the use of psychedelics for the treatment of mental disorders.

Objective

To provide an overview of salient themes in patient experiences of psychedelic treatments for mental disorders, presenting both common and diverging elements in patients’ accounts, and elucidating how these affect the treatment process.

Methods

We systematically searched the PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Embase databases for English-language qualitative literature without time limitations. Inclusion criteria were qualitative research design; peer-reviewed studies; based on verbalized patient utterances; and a level of abstraction or analysis of the results. Thematic synthesis was used to analyze and synthesize results across studies. A critical appraisal of study quality and methodological rigor was conducted using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP).

Results

Fifteen research articles, comprising 178 patient experiences, were included. Studies exhibited a broad heterogeneity in terms of substance, mental disorder, treatment context, and qualitative methodology. Substances included psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), ibogaine, ayahuasca, ketamine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). Disorders included anxiety, depression, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. While the included compounds were heterogeneous in pharmacology and treatment contexts, patients reported largely comparable experiences across disorders, which included phenomenological analogous effects, perspectives on the intervention, therapeutic processes and treatment outcomes. Comparable therapeutic processes included insights, altered self-perception, increased connectedness, transcendental experiences, and an expanded emotional spectrum, which patients reported contributed to clinically and personally relevant responses.

Conclusions

This review demonstrates how qualitative research of psychedelic treatments can contribute to distinguishing specific features of specific substances, and carry otherwise undiscovered implications for the treatment of specific psychiatric disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Patients compare psychedelic treatments favorably with conventional treatments, emphasizing the importance of non-pharmacological factors such as trust, safety, interpersonal rapport, attention, the role of music, and the length of treatment sessions. |

Pharmacologically distinct psychedelics exhibit overlapping therapeutic processes for different mental disorders, including insights, altered self-perception, increased feelings of connectedness, transcendental experiences, and an expanded emotional spectrum. |

Patients frequently report on clinical effects beyond their own psychiatric diagnosis, which may be indicative of the cross-diagnostic action of psychedelic drugs, by setting in motion therapeutic processes that address core elements of a shared psychopathology across mental disorders. |

1 Introduction

The recent resurgence of clinical interest in the use of psychedelics for the treatment of mental disorders is evidenced by a sharp increase in studies and publications. After a decades-long research hiatus, psychedelics have been investigated as potentially effective treatments for several mental disorders, including substance use disorders (SUDs) [1,2,3,4]; post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [5,6,7,8,9,10]; anxiety, and depression secondary to a life-threatening illness [11,12,13,14]; social anxiety in autistic adults [15]; obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) [16]; depression [17,18,19,20,21,22]; and suicidal ideation [23]. Psychedelic drugs include a range of pharmacologically diverse substances comprising ‘classic’ serotonergic psychedelics (psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide [LSD], and the dimethyltryptamine [DMT]-containing ayahuasca), entactogens (e.g. the serotonin-releasing drug 3,4-methyenedioxymethamphetamine [MDMA]), the atypical psychedelic ibogaine and dissociative anesthetics such as the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonist ketamine. All these substances can induce alterations of conscious states, as well as a wide range of psychological, cognitive, emotional, and biological effects that may be relevant for their therapeutic action, when administered within a (psycho)therapeutic context [24,25,26,27,28].

The safety, clinical benefits and therapeutic outcomes of these interventions are thought to be fundamentally reliant on a supportive environment [29, 30], with ‘set’ and ‘setting’ playing a crucial role [31, 32]. ‘Set’ includes internal, psychological variables such as personality, expectations, suggestibility, preparation, intentions, and mood and psychopathology, while ‘setting’ is understood to mean the external environment in which the experiences take place, including the physical, interpersonal, and broader social and cultural contexts [33,34,35,36]. Therapeutic use of psychedelics takes place in different settings. Modern clinical research with psilocybin, LSD and MDMA is typically conducted in the context of so-called ‘psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy’, which is a complex and variable modality that involves the administration of a psychedelic drug to facilitate or catalyze a therapeutic process [37]. Typically, this takes place in the presence of one or two therapists, and often involves the use of music to facilitate an introspective experience [33, 38, 39]. The Amazonian brew ayahuasca is typically consumed in traditional shamanic, religious, and hybrid ceremonial settings [40], whereas ibogaine is administered in both unlicensed ‘medical subcultures’ [41] and in private clinics such as in Mexico and New Zealand [42, 43]. On the other hand, the atypical psychedelic ketamine is normally administered as a standalone pharmacotherapy in a clinical setting [44].

It has been suggested that the influence of these extrapharmacological variables contributes significantly to the substances’ pharmacological qualities [33, 35], as evidenced by the high variability of individual experiences. Studies have emphasized the importance of the subjective experience [29], and several potential psychological mediators for therapeutic outcomes have been postulated in treatments with psychedelics, e.g. (sustained) changes in openness [45,46,47], prosocial feelings [45, 48], increases in suggestibility [49], meaning making [50], self-efficacy [51], and connectedness [52, 53]. Furthermore, psychological flexibility [54], emotional breakthroughs [55], psychological insights [51], the loss of sense of self (‘ego dissolution’) sometimes resulting from mystical or peak experiences [29, 56,57,58], and experiences of awe [59] have been mentioned.

A close examination of patients’ experiential accounts could increase our understanding by providing more detailed insight into these and other underlying (psychological) mechanisms. Given the highly personalized nature of psychedelic-induced patient experiences, quantitative measurements might not capture the full spectrum of phenomena experienced by patients. Qualitative inquiry is typically concerned with understanding the how, what, or why of a particular phenomenon and can generate a more holistic account of the issue being studied [60, 61]. This is especially relevant in this emerging field of research. This makes qualitative research well-suited to explore the rich subjectivity of respondents’ inner experiences, their attributions of meaning, the treatment context, and help inform a more detailed understanding of these complex interventions and underlying psychological mechanisms. These may in turn better tailor future research as well as inform and improve therapeutic effectiveness. Qualitative inquiry can also complement quantitative research by generating, rather than validating, hypotheses, which can be tested using quantitative instruments.

While some qualitative research efforts have been directed at exploring the role of the subjective psychedelic experience in the treatment of mental disorders, to date no systematic review exists. This article aims to address this lacuna by presenting an overview of the available qualitative research. Identifying salient themes across studies, this review presents both common and diverging elements in patients’ accounts of their experiences, how they relate to their disorders, therapeutic processes, and personally and clinically significant outcomes. A systematic literature review was conducted of qualitative studies that address what patients report after taking a psychedelic substance in the context of treatment of a mental disorder.

2 Methods

We systematically identified and reviewed the selected studies using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, which offer an extensive checklist and flowchart to improve the quality of systematic reviews [62].

2.1 Selection Criteria

For this systematic review we selected papers that described patient experiences after taking a psychedelic for the purpose of treating a mental disorder. The eligibility criteria for inclusion in the review were qualitative research design; peer-reviewed studies in English; based on verbalized patient utterances; and a level of abstraction or analysis of the results. Eligibility criteria for inclusion were based on a modified PICo framework for qualitative reviews [63]. We employed a broad definition of psychedelics (see Table 1).

2.2 Search Strategy and Study Selection

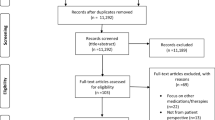

We conducted a systematic search between 5 and 12 March 2019. The PubMed, MEDline, PsycINFO, and EMBASE databases were searched extensively and systematically without time limitations, using combinations of both index terms (Medical Subject Headings [MeSH] in PubMed, Emtree in Embase, and Thesaurus in PsycINFO) and free-text terms in two categories. The first category included a broad range of psychedelic substances, including the atypical psychedelics ketamine, ibogaine, and MDMA. The second category involved the type of data that were gathered (e.g. “patient experience*”, “phenomenology”, “patient perspective*”, “participant experience*”, “subjective experience*”) and the qualitative methodology (e.g. “qualitative research”, “semi-structured interview*”, “focus group*”, “qualitative methods”, “thematic analysis”, “grounded theory”, “interpretative phenomenological analysis”). All databases were searched using “OR-relations” within these categories, and “AND-relations” between categories. A detailed account of the searches can be obtained from the first author upon request. The systematic search was complemented by hand searching, including reference lists of identified articles as well as relevant, non-indexed journals. The selection process was conducted according to the eligibility criteria as presented in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1.

2.3 Data Analysis and Synthesis

Qualitative research seeks to develop a contextual understanding of behavior in the natural environment it observes. This does not mean that generalizability is impossible, but rather that theoretical generalization, i.e. transference, must be separated from statistical significance [64]. Whereas systematic review methods are well developed for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), no single preferred methodology exists to guide analysis and synthesis of qualitative data [65, 66] or to guide critical appraisal of study methodology and validity [67,68,69]. For this review, we employed thematic synthesis [70], based on thematic analysis [71], as this approach is particularly useful for bringing together heterogeneous studies [72]. Since we did not want to exclude potentially relevant articles a priori, we conducted a post-synthesis sensitivity analysis [68] using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist, also in order to assess the methodological rigor of the studies [73].

Thematic synthesis took place in three stages. First, all included articles were read and re-read carefully several times by the first author, allowing him to become thoroughly familiar with the content of the material. We were primarily interested in patient experiences, therefore, as our primary data, we took the results sections of all articles, including the categories and subthemes identified by the articles’ authors. The first author then interpreted the data, and assigned primary codes. Parallel, he noted down comments, observations and reflections. Second, these codes were examined for similarities and differences, and were rewritten with a higher level of (psychological) abstraction into themes. Finally, these themes were subsequently reanalyzed and grouped together by all authors, based on conceptual similarities; these clusters comprised major themes and were given a descriptive label. We paid specific attention to potential similarities and differences by substance. All authors discussed additional analyses, and, where needed, categories were refined.

3 Results

3.1 Study Selection

The initial literature search identified a total of 1660 results (PubMed, n =1025; PsycINFO, n =232; and EMBASE, n =403, and additional hand searches yielded five extra records. After removal of duplicates, the remaining 1472 publications were screened. Screening titles and reading abstracts resulted in the exclusion of 1375 titles. Ninety-seven full-text articles were obtained and read. Relevant information was extracted and assigned an additional code of yes/no/maybe, according to the inclusion criteria. Seventy-nine additional articles were excluded for not meeting the criteria (see Fig. 1 for a further breakdown of the reasons). Three articles were excluded at a late stage: one study on the clinical use of MDMA [74] was ultimately excluded as it did not target a specific mental disorder and had unclear research methodology and study aims. Two recent psilocybin studies [75, 76] were also excluded as they presented a series of case studies, without additional analysis. Finally, 15 studies, with a total of 178 patients, were included in the systematic review.

3.2 Study Characteristics

All articles were published between 2014 and 2019. Where reported, respondents’ ages ranged from 21 to 67 years, and the number of included subjects ranged from 4 [77] to 22 [78, 79]. Studies were heterogeneous in terms of substances, population/mental disorders, contexts, and qualitative research methodologies. For an overview of all substances and disorders, please see Table 2.

All studies on psilocybin, LSD, ketamine, and MDMA took place in the context of clinical research in the US [80,81,82,83,84], Switzerland [85] and the UK [53]. Ibogaine treatments took place in treatment centers in Mexico [86] and Brazil [78, 79], while ayahuasca was used in ceremonial [87, 88], religious [89] or treatment contexts [90].

3.3 Critical Appraisal of Study Quality

The quality of the included studies varied. Based on the CASP criteria [73], one study could be considered as low to medium quality [78] and two as medium quality [86, 89]. The majority of the studies were rated as medium/high [79, 80, 85, 90] to high quality [77, 81,82,83,84, 87, 88, 91]. Overall, we found the validity, ethical considerations, and value of the studies to be of high quality. Critical reflections on the researchers’ roles and relationship with participants varied widely, but this was not reflected in the overall quality assessment. Across the board, the rigor of the data analysis varied most and had the most room for improvement. An overview of the quality assessment of all included papers is presented in Appendix A. In order to examine the extent to which quality variations may have influenced the thematic synthesis, we conducted a post hoc sensitivity analysis. Assessing the relative contribution of the included studies to the thematic synthesis and overall themes, we found that lower-quality studies and studies with divergent research aims contributed comparatively less to the synthesis. The specific study aims and objectives correlated most clearly with the thematic synthesis. For instance, studies that aimed to address patients’ subjective experience of a substance’s psychoactive effects [79, 84, 86, 88] contributed mostly to the phenomenology section. The studies that focused on patient experiences of the therapeutic process [82, 85, 88], aimed to increase the understanding of these complex treatments [81, 82, 85, 90], or (also) aimed to characterize, describe, or determine potential therapeutic mechanisms, effects, and processes [53, 82, 83, 85, 87, 90] contributed most to the perspectives on the intervention, therapeutic processes and outcomes. While we found quality differences, no articles were excluded based on our quality assessment. A complete overview of study aims, qualitative methodology and other study characteristics can be found in Table 3.

3.4 Nature of Patient Experiences

We primarily assessed descriptions and narratives of patient experiences. Our analysis revealed that all authors discussed one or more of the following: (1) phenomenology of the experience; (2) perspectives on the intervention; (3) therapeutic processes; and (4) outcomes of the intervention. Below we elaborate on each of the subthemes falling under these main themes, and provide key examples of each of the themes and results. In many instances, themes were reported for different substances and/or disorders. Where this was not the case, this is made explicit in the text. Quotes are included to illustrate patient experiences.

3.4.1 Phenomenology of the Psychedelic Experience

Several, but not all, studies explicitly addressed the phenomenology of the acute, inner experience induced by different psychedelic substances [79, 81, 82, 84, 86]. In this review, we report phenomena that were not characterized as therapeutic processes alone or that did not constitute separate themes in the synthesis, while recognizing that both thematic categories are closely intertwined. Phenomenological experiences were reported on the level of altered sensory perception (including synesthesia and the perception of time), visions and visuals, and somatic effects. Respondents frequently alluded to the ineffability of the experience.

A slowed (or completely absent) perception of time and unusual bodily sensations were specifically mentioned by participants taking ketamine [84], while auditory effects, such as zapping or buzzing sounds, were only mentioned for ibogaine experiences [79, 86]. Abstract and transient visual phenomena (such as seeing animals, complex patterns, landscapes) and visions (immersive and personally meaningful) were reported by respondents in studies with psilocybin and ibogaine [79, 81, 82, 86]. To varying degrees, these visions contained autobiographical, relational, imaginary, dreamlike, indigenous, religious, and other elements.

“It sent me back to when I was very first born and felt like I was inside the womb … I fought the devil … he was telling me to give up and die, but I didn’t want to and I somehow beat him. And that I thought was my addiction at the time … I was able to float up in the atmosphere and I felt my grandma, I just felt her presence everywhere and I realized that she was all around the whole time.” [86] [ibogaine, SUD].

Notably, participants who had taken ibogaine reported physically unpleasant sensations, neurological effects and perceptual alterations that were not described in other studies [79, 86], although unusual and strange bodily sensations were also reported for ketamine [84]. Experiences of the brain being reorganized, accompanied by ‘zapping’ sensations, were described in studies with ibogaine [79, 86] and psilocybin [91].

“There was a little NASA space guy that came flying in and he was zapping my brain … it felt like they were scrubbing my brain, they were just doing surgery… it felt like brain receptors being cleaned.” [86] [ibogaine, SUD].

Somatic experiences were often connected to meaningful insights for participants with eating disorders, as evidenced by the following quote:

“I saw myself as a rotting, decaying skeleton and then I saw myself as this beautiful full-bodied, just beautiful woman with this long hair, and I, like, I wanted to be that woman. I wanted to be that full, loving woman that has so much to offer my family and world. It was, and then I felt my ribs and I could feel them, they were so hollow and I was just, I was like, I can’t wait to get back and just start gaining some weight.” [87] [ayahuasca, eating disorder].

Several respondents, especially in studies with psilocybin [77, 81, 82], and also with other substances, remarked on the ineffable nature of the experience, their inability to adequately put it into words, leading some to mention that it was easier to describe the emotional impact of the experience than the specific content.

“It was a feeling beyond an intellectual feeling—it was a feeling to the bottom of my core … that’s one reason that it’s hard to talk about … it’s beyond words.” [81] [psilocybin, end-of-life anxiety].

3.4.2 Perspectives on the Intervention

How the treatment itself was experienced proved an important aspect for many of the respondents. This main category encompasses the following subthemes: (a) the context and structure of the treatment, and (b) comparisons with conventional treatments.

3.4.2.1 Context and Structure of the Intervention

Independent of substance or disorder, many patients reported how they experienced the treatment, and the ways interventions were structured. Trust and a good connection or rapport with study guides, therapists and ceremonial leaders were explicitly mentioned as important therapeutic aspects [53, 80, 83, 87, 89].

“It’s not just the psilocybin sessions [but] it’s that human connection, and the support that comes with that human connection, that ultimately leads to success at the end of the day.” [83] [psilocybin, smoking cessation].

Many respondents also noted the importance of the preparatory sessions [53, 80, 83, 90]; for example, in preparing them for the potential of having challenging experiences [53]. The added value of integration sessions was also mentioned frequently [53, 80, 82, 83, 87].

“I mean besides the ayahuasca itself, besides the medicinal quality of you know, chemically what ayahuasca can do, I would say that (the most important therapeutic elements were) the trust, therapeutic trust in the medicine men and as well, the follow-up. The psychotherapy follow-up was crucial. And before and after (ceremony) I would say. I don’t know if I would ever recommend an ayahuasca ceremony without that therapeutic, the first one at least, without that therapeutic follow-up.” [87] [ayahuasca, eating disorder].

Music was used in all studies with psilocybin, MDMA, and LSD, as well as in ayahuasca ceremonies. One ibogaine study was conducted in silence [78, 79]; the third ibogaine study [86] and the ketamine study [84] did not report on this aspect. Only patients in various psilocybin studies (for end-of-life anxiety, depression, and smoking cessation) [53, 82, 83] reflected on the role and function of music, stating that it served as a conduit, enabling them to experience and surrender to painful emotions or memories.

“Music was really how everything was conveyed to me, it all came through the music … like everything that I experienced did not really happen in the English language, it kind of happened through the music, like the music was the conduit for this experience to happen.” [82] [psilocybin, end-of-life anxiety].

In contrast with many other classes of psychoactive substances (ketamine being a possible exception [92, 93]), psychedelics do not lead to addiction or dependence [25, 94], and some respondents with SUDs remarked on these notable differences [79, 83]. In two of the studies that provided a single psilocybin session, several patients expressed the wish for additional sessions [82], and one study reported that several patients actively sought out extramedical psilocybin sessions for this reason [53].

3.4.2.2 Comparisons with Other Treatments

Irrespective of disorder or substance, respondents reflected on different elements of the intervention, comparing these with previously experienced conventional treatments. Many also reflected on previous strategies in coping with their disorder, and how these were addressed, often less effectively, in previous treatments [53, 78, 81]. Below, we provide some examples of particular personalized experiences of psychedelic treatments. These are often juxtaposed generally with standard treatments, although respondents did not always specify what these treatments entailed.

“Standard approaches—I guess to summarize—are very top-down … like suppressing symptoms so that you can become functional, whereas the work with the medicine [ayahuasca] … is more of a bottom up approach that is very much really rewiring things, it’s getting to the root cause and bringing in what was missing and resolving it on a deep, deep level that doesn’t I don’t think really get fully explored or touched upon in standard approaches.” [88] [ayahuasca, eating disorder].

Respondents from across the spectrum of disorders and substances compared their psychedelic treatments favorably to previously undergone conventional treatments, calling it, for example, more effective [88], less normative [89], or more rapid [78], by focusing on inner processes as opposed to talk therapy [85] and by providing healing beyond what they found in conventional treatments [80]. Patients also favored the length of the sessions and attention they received [53].

“In usual psychotherapy it is mainly about talking, about words. In LSD-assisted psychotherapy it is mainly about inner processes, inner change, inner experience, it gets enriched by it.” [85] [LSD, end-of-life anxiety].

Many respondents reflected upon the intervention’s effectiveness for the specific disorder they were struggling with [78, 80, 88, 90]. In the below quote, a patient with PTSD mentions several crucial elements that together enabled him to address his (war-related) trauma.

“I think that the MDMA gave me the ability to feel as though I was capable and safe of tackling the issues. Whereas before I feared those thoughts and I tried to avoid them at all times, and avoid things that reminded me of those thoughts, I think it allowed me to feel safe in my space. Of being able to fight it. I felt like I had the ability and tools, whereas before I was unarmed, unarmored, and had no support. And this type of environment, with [the therapists], the catalyst drug, and everything else, it felt as though I had backup. Now it was safe and I had my tools and weapons to be able to tackle the obstacles that I never had before.” [80] [MDMA, PTSD].

Multiple patients who underwent ayahuasca ceremonies to treat eating disorders provided suggestions for integrating these with conventional eating disorder treatments [88]. Respondents in one study, when prompted, actually stated becoming more open towards future conventional therapies, despite having undergone multiple therapies without success [80].

3.4.3 Therapeutic Processes

Potential psychological or therapeutic processes or mechanisms of action constituted a major theme that, in one way or another, recurred in all studies included in this review. These cover several categories, which overlap to a certain degree. Often, there was no clear-cut distinction between the different therapeutic mechanisms, and elements of one therapeutic mechanism blended into others. Acknowledging their interrelatedness, in this review we report on the following categories: (1) insights; (2) altered self-perception; (3) feelings of connectedness; (4) transcendental experiences; and (5) expanded emotional spectrum. These are briefly discussed below.

3.4.3.1 Insights

One of the most frequently mentioned themes was achieving insights, most crucially into one’s self, alternatively called improved self-awareness or self-understanding. This was also frequently mentioned as an outcome of the intervention. For various disorders and substances, patients reported improved insights in their disorder, its root causes, and related behaviors [80, 83, 87, 88, 90].

“I remember having a ceremony where I really saw that at the time binging and purging and restricting were actually adaptive coping mechanisms; at the time, they were the only coping mechanisms that I actually knew to use to deal with the difficulty that I was experiencing, that I had no words for and that no one was asking about.” [87] [ayahuasca, eating disorder].

These insights resulted in an improved understanding of the underlying disorders, the root psychological causes [87], an improved understanding of the underlying causes of addiction [90], and, more specifically for patients with eating disorders, somatic insights [87]. Respondents also gained crucial insights into their behavior towards others with regard to relationships with friends, family or partners [78, 82]. Specific examples of these mechanisms were visions of an autobiographical nature [79], a new understanding of death and dying [81], and changes in perspective, also referred to as ‘de-schematizing’ [85]. In one study, patients describe how insights continued to evolve across and between psilocybin sessions [83].

3.4.3.2 Altered Self-Perception

Alterations in how the self was experienced during the sessions played an important role in many studies in this review. The emphasis on changed perceptions of, and perspectives on, one’s self was mentioned variably as increased self-efficacy [78], decreased self-criticism [86], facilitated by a lowering of psychological defense mechanisms [53], and increased self-awareness [78, 80, 87]. Closely associated were experiences of greater self-love, self-care, self-confidence, self-acceptance, self-awareness, self-worth, self-control, self-esteem, self-compassion, and self-forgiveness.

“I learned a lot. I learned a lot about myself. I’d gotten to the point of questioning myself, my own morals, and for someone who hasn’t done this stuff, they’re not going to understand. You can see yourself like you can read a book and see everything that you stand for and kind of analyze your own self, your own thought, your own reasoning.” [80] [MDMA, PTSD].

Related to this were experiences of a dissolving or loosening sense of self, which often gave way to a wider perspective, which was linked to transcendental experiences (see below).

“Ayahuasca helped me deeply connect with myself so that self-love has been the prevalent priority over self-criticism that […] self-love became more important and more prevalent. And that to me is the antidote for an eating disorder.” [87] [ayahuasca, eating disorder].

3.4.3.3 Connectedness

Increased connection, or connectedness, was a central theme in one study on psilocybin treatment for depression [53]. Across other studies with psilocybin, as well as with ibogaine and ayahuasca, respondents also describe (re)connection on different levels; internally (with their emotions, senses, parts of their self and their identity), as well as externally (with others, i.e. partners, family members, friends [53, 78, 83, 88], and also with nature and the world at large [53, 81, 82].

“(The psilocybin) just opens you up and it connects you … it’s not just people, it’s animals, it’s trees—everything is interwoven, and that’s a big relief … I think it does help you accept death because you don’t feel alone, you don’t feel like you’re going to, I don’t know, go off into nothingness. That’s the number one thing—you’re just not alone.” [81] [psilocybin, end-of-life anxiety].

Experiences of interconnectedness, a felt sense of the unity of all things, were described explicitly by patients in various psilocybin studies [53, 81,82,83].

“(During the dose) I was everybody, unity, one life with 6 billion faces, I was the one asking for love and giving love, I was swimming in the sea, and the sea was me.” [53] [psilocybin, depression].

3.4.3.4 Transcendental Experiences

Mystical, religious or spiritual aspects of healing were widely reported in patients’ healing experiences in treatment with ayahuasca [88, 90], ibogaine [79, 86], and psilocybin [53, 81,82,83], as well as for different mental disorders. These were related to transpersonal experiences, feelings of awe and transcendence, a dissolving of the self, a connection to greater forces, an interconnectedness with all life, and the unity of all and everything.

“It was like being inside of nature, and I could’ve just stayed there forever—it was wonderful. All kinds of other things were coming, too, like feelings of being connected to everything, I mean, everything in nature. Everything—even like pebbles, drops of water in the sea … it was like magic. It was wonderful, and it wasn’t like talking about it, which makes it an idea, it was, like, experiential. It was like being inside a drop of water, being inside of … a butterfly’s wing. And being inside of a cheetah’s eyes.” [82] [psilocybin, end-of-life anxiety].

3.4.3.5 Expanded Emotional Spectrum

Across substances and disorders, respondents report on the wide emotional scope of the experience, the increased access to a range of emotions, and the importance of the emotional content of their experiences. Emotions ranging from bliss, joy, peace, and love on one end of the spectrum, to anger, anxiety, terror, dysphoria, and paranoia on the other end, were reported by respondents in the majority of the articles.

“Emotionally it was a roller coaster ride … The first time it was very brutal, painful, at least emotionally very painful. I could not even say in which direction—it just hurt, like heartache, like being disappointed, like everything you once had experienced as a negative feeling. … It was pure pain. Pain of memories, well, or memory of pain. … it was quite hard. During the second time it was sublime. Really. Love, expansion, holding, I knew that this sometimes happens, that participants talk about spiritual experiences. I thought they just meant this dissolution of oneself – everything is okay, everything is great. That was a very important experience for me. Very, very important.” [85] [LSD, end-of-life anxiety].

Sometimes a change in mood from their usual emotional state was considered therapeutic in itself.

“That place was um, serene and peaceful, and um, just such a burden was lifted from me. And it was refreshing to feel something that was such a change from what I normally feel.” [84] [ketamine, depression].

In addition to accessing previously inaccessible emotions, some respondents also describe an improved ability to process unresolved emotions [87, 88]. Participants regularly mentioned that experiential sessions could be challenging or painful. These emotionally difficult experiences were often considered therapeutically useful, especially when participants managed to transform negative into positive emotions, which often had a lasting impact [53, 78, 81, 82, 85, 88]. Closely related was the therapeutic importance of emotional catharsis, or the release of often painful emotions or memories [53, 77, 79, 82, 85]. This tied in closely with participants’ ability to accept, and surrender to, the difficult emotions they experienced [53, 81, 82, 85, 88].

“Excursions into grief, loneliness and rage, abandonment. Once I went into the anger it went ‘pouf’ and evaporated. I got the lesson that you need to go into the scary basement, once you get into it, there is no scary basement to go into (anymore).” [53] [psilocybin, depression].

In addition to accepting challenging emotional states, accepting one’s situation (or more specifically, one’s body and illness), particularly in the face of one’s impending demise, appeared to play an important role for patients with a terminal diagnosis [81, 82, 85].

“I kind of accepted my body for what it is, and I think up until that point I resisted that … I saw this body for what it’s worth. I picked it, it’s mine. It’s more matter-of-fact—this is what it is. I think that acceptance has been liberating.” [81] [psilocybin, end-of-life anxiety].

3.4.4 Outcomes of the Intervention

It sometimes proved difficult to distinguish outcomes of the treatment from processes participants underwent and the mechanisms described above. In many cases these overlapped: aspects that were experienced during the experiential sessions proved to have a lasting impact. Subthemes in this category include (1) symptom relief; (2) perspectives of self; (3) sense of connectedness; (4) mood and emotional changes; and (5) quality of life.

3.4.4.1 Symptom Relief

In many studies, participants experienced significant relief from the disorder they were treated for, including reductions in eating disorder-related thoughts and symptoms, PTSD symptoms, anxiety, depression, and substance use. Reductions in withdrawal and reduced (in some cases completely vanished) craving were mentioned by participants in all studies on SUDs [77, 78, 83, 86, 89, 90]. Remarkably, decreased drug, alcohol, and medication use were also reported in studies with MDMA, ayahuasca and psilocybin that did not deal directly with substance use [53, 80, 87].

“When I first started [the study] I was taking 10 different things. And now no blood pressure medicine, no anxiety pills, no pain pills.” [80] [MDMA, PTSD].

More broadly, outcomes were often seen beyond the realm of the initial diagnosis, and, in fact, participants often considered these other results to be more significant.

“This is about a smoking study, I keep forgetting that. Because there’s so much more that happened… (Smoking) just seems so petty compared to some of the stuff that was happening.” [83] [psilocybin, smoking cessation].

3.4.4.2 Perspectives of Self

Therapeutic outcomes were often discussed in the realm of the self. Previously mentioned shifts in self-perception as therapeutic process often remained with patients, who described being better able to understand, reflect on, or be aware of themselves [53, 80, 83, 87], experienced greater self-confidence and self-esteem [87], as well as self-acceptance [86], and found themselves better able to feel love and compassion for themselves [80, 87, 88], leading to better self-care [88].

“[Ibogaine] gave me more self-love … I’m not so hard on myself.” [86] [ibogaine, SUD].

3.4.4.3 Sense of Connectedness

Enhanced (inter)connectedness was reported across substances, both during sessions and afterwards, with respondents alluding to positive changes in friendships and improved relationships with family members [53, 78, 80]. One article describes increased altruism and prosocial activities in general [83].

“[I feel] love, compassion, and it’s not just for family, it’s for everyone…[my parents and I] have a much better relationship now, no doubt… the study helped me really get there.” [80] [MDMA, PTSD].

“I think right after the trips … certain changes happened … Same things were not equally important anymore. A shift in values. … To take time to listen to music, to listen to music consciously. Maybe that material values were not that important anymore. That other values have priority. Health and family, such things… When you have a job and the job has priority and the family comes last. You don’t even notice it anymore. To realize there, stop, what is actually important? That the family is fine, that the kids are doing well …” [85] [LSD, end-of-life anxiety].

3.4.4.4 Emotions

Participants also reported improved mood, greater optimism, an increased emotional repertoire, and positive emotional changes [53, 78, 82, 84]. In some cases, this included increased confidence in dealing with future adverse situations, such as a relapse in symptoms or the recurrence of their illness [53, 81].

“Though my problems obviously have not stopped to happen and appear, I changed in the face of them. So, I get to the end of my day very grateful, very happy.” [78] [ibogaine, SUD].

3.4.4.5 Quality of Life

Across the board, respondents in these studies describe positive and often lasting changes in quality of life and well-being [78, 82, 85], experiencing an increased sense of peace and mental space in daily life [53, 81, 84]. Respondents also mentioned an increased sense of purpose or meaning in life [81]. Increased appreciation of beauty in art, music, and nature was reported by several participants [53, 83].

“A veil dropped from my eyes, things were suddenly clear, glowing, bright. I looked at plants and felt their beauty. I can still look at my orchids and experience that: that is the one thing that has really lasted.” [53] [psilocybin, depression].

In one study, participants report being able to maintain this sense of well-being even after relapsing or after symptoms return [53]. These positive changes in quality of life were reflected in the positive changes participants made, such as re-engaging with previously enjoyed activities such as practicing sports, changing nutritional habits, reading poetry and other hobbies. Changes in quality of life seemed associated with revised priorities in life or more clarity around values, as exemplified by one participant.

“I had lost desire to do anything, I lacked will to go to the gym, to the park, the cinema, I only wanted to stay home. After ibogaine the first thing I wanted to do was going to the park, to the movies” [78] [ibogaine, SUD].

4 Discussion

This paper is the first to systematically offer an overview and thematic synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature that describes patient experiences of treatments using a psychedelic substance for the treatment of a mental disorder. All included qualitative studies were published in the last 5 years, which is indicative of both the increasing interest in therapeutic applications of psychedelics and a growing appreciation of qualitative methods in clinical research; half of the studies complemented quantitative measurements in clinical trials. We used a broad definition of psychedelics that included a range of pharmacologically diverse substances: the ‘classical’ serotonergic psychedelics psilocybin, LSD, and ayahuasca; MDMA; ibogaine; and ketamine, which were used to treat several distinct mental disorders. This was driven by the presumed shared phenomenology of psychedelics [26], combined with the strong phenotypic overlap or high comorbidity between psychiatric diagnostic categories [95], the genetic overlap between mental disorders [96], as well as the absence of reliable biomarkers [97] or natural boundaries [98, 99] to distinguish disorders, and also the fact that diagnostic categories can change over time [99,100,101]. Furthermore, there is evidence to support the idea that the subjective experience induced by these compounds is relevant for their therapeutic effect. To some degree, this also holds true for ketamine, which is nevertheless predominantly administered as a standalone pharmacotherapy [2, 27, 102,103,104]. In some instances, a single substance (e.g. psilocybin) was used for the treatment of varying mental disorders: depression, nicotine dependence, alcohol use disorder and end-of-life distress. Similarly, different substances (psilocybin, LSD, ayahuasca and ketamine) were studied for the treatment of the same disorder (e.g. depression).

Despite the oft-reported ineffability (the inability to adequately verbalize the phenomenological content of their experiences), respondents in several studies did offer rather detailed descriptions of their experiences, as well as reflections on the intervention. Not all studies described phenomenological aspects of the acute experience; this is most likely related to the specific methodology used or the researchers’ areas of interest.

For a critical appraisal of the qualitative assessment of the participants’ experience, it is important to understand when, by whom, and how data collection and analysis were performed. Given the timing of interviews, which varied considerably (from 1 week to 1 year post-session; for an overview see Table 3), also within studies, respondents may not always have had enough time or distance to gain a broader perspective on their experiences, or to experience longer-term changes in the first place. As some respondents alluded to, insights were not always gained during the interventions themselves, but rather between sessions, or following (integrative) sessions [83].

Interestingly, in some studies, treatment-resistant patients in placebo groups reported enduring, clinically significant improvements (see, for example [8]). This may illustrate the importance attributed to extrapharmacological factors that were mentioned by respondents: trust, interpersonal rapport, attention, the length of treatment sessions, and a safe treatment setting. However, since several studies were uncontrolled or open-label, contextual factors could not be discriminated from drug effects. Music was also frequently mentioned as an important element. This is in line with the role of music in both traditional ceremonial psychedelic use and present-day clinical psychedelic research [105], suggesting that therapeutic benefits may be promoted not only by the drug but by its interaction with music [106]. Music is typically used to elicit personally meaningful experiences by intensifying emotions and mental imagery; guiding or supporting emerging experiences; and by providing non-verbal structure, grounding, and continuity [33, 105, 106].

Therapeutic alliance is considered a strong predictor of treatment success in conventional psychotherapy [107]. The value respondents attributed to surrendering to and overcoming intense, emotionally challenging experiences suggests that therapeutic alliance may be crucial in establishing patient safety. Participants also stressed the importance of preparatory and integration sessions in this respect.

This review revealed several therapeutic mechanisms, all reported for multiple substances and disorders. Mechanisms include gaining insights, altered self-perception, increased feelings of connectedness, transcendental experiences, and expanded emotional spectrum. These mechanisms often overlapped; elements of one therapeutic mechanism also featured in descriptions of others. For example, insights into relationships with family or friends related to experiences of connectedness, while experiences of interconnectedness can also be labeled as mystical. Likewise, an emotional breakthrough can follow insight into the origins of one’s depression and may be prompted by having surrendered to a particularly challenging experience. It is plausible that multiple mechanisms, or elements thereof, may act together in producing therapeutically relevant outcomes.

Descriptions of therapeutic processes were closely intertwined with the phenomenology of the subjective experience, and were often difficult to distinguish from treatment outcomes. This can be explained by the presumed therapeutic effect of the subjective experience itself, making it difficult to disentangle the two. It is also partially inherent to the interpretative process of analyzing and synthesizing qualitative data. Patient reports can be ambivalent and it is not always clear whether they refer to acute experiences or longer-term outcomes. Patients reported a range of insights, changed perspectives and increased understanding, into the self and (root causes of) their disorder. Insights and altered self-perception were related to outcomes such as increased self-love, self-worth, and self-compassion. Again, these were described irrespective of a specific disorder or substance. Some participants reported experiences of ego dissolution, often linked to feelings of connection to larger existential powers. These spiritual or mystical aspects of healing were also mentioned across substance and disorder. Both early [108,109,110] and present-day psychedelic studies [13, 14, 51, 111, 112] have found significant relations between mystical experiences and therapeutic outcomes. Experiences of interconnectedness emerged as a theme in all psilocybin studies; ‘connectedness’ constituted a major theme in one study [53], prompting new hypotheses and the development of new scales [52]. Psychedelics may intensify emotions and have been used for this purpose since early psychotherapy research in the 1950s [113]. Patients also considered improved access to a greater range of emotions and emotional content important, particularly being able to process and release previously unresolved or inaccessible emotions. The fact that catharsis or emotional breakthrough may act as a mediating determinant in long-term positive changes in well-being is partially validated by recent online surveys [55]. Furthermore, patients explicitly attributed value to overcoming difficult experiences. These are thought to be a mediating factor in both negative and positive long-term effects of treatment with psychedelics [114,115,116]. Evidence from survey studies indicated that the peak intensity of challenging experiences was associated with positive long-term outcomes, provided resolution was achieved, as longer duration was predictive of negative outcomes [116].

Respondents reported both clinically and personally meaningful outcomes. An interesting finding was that many patients reported benefits beyond symptom reduction. In fact, they did not always consider symptom reduction to be the primary benefit. In all studies on SUDs, respondents reported decreases in craving and withdrawal symptoms [77,78,79, 83, 86, 89, 90]. Interestingly, these reductions were also reported by patients with depression, eating disorders, and PTSD. While there has been substantial anecdotal, albeit not clinical, evidence to suggest that ibogaine in particular is capable of attenuating (opioid) withdrawal [43, 117], reduction and elimination of craving and withdrawal symptoms were also reported in studies with ayahuasca [90], psilocybin [83] and MDMA [80]. Since many mental disorders have high comorbidity with SUDs [118,119,120,121], this may explain why the therapeutic action of psychedelics may need not be limited to a specific disorder or (set of) symptoms.

This review had several limitations. First, studies included in this review varied in terms of design, qualitative research methodology, analysis methods, timing of the interviews, and overall quality. These factors may have influenced results and reduced comparability. Second, we considered mental disorders non-specifically. Compounded by the diversity of substances and heterogeneity of treatment contexts, it could be argued that this review compared orchard-grown apples with indoor-cultivated oranges. Given the overlap in phenomenology of these diverse substances, the various mental disorders, and combined with the novelty of this field, and the relative paucity of the available evidence, this review was meant to serve an exploratory purpose and was not intended to yield comparative results (as, indeed, this would require more studies per substance and per disorder, as well as a multidimensional matrix). As a result, substance-specific characteristics for the treatment of specific disorders could not be teased out. It has been suggested that MDMA, for example, possesses characteristics that make it uniquely useful for the treatment of PTSD [122]; the same has been argued for ibogaine in the treatment of SUD [42]. The high heterogeneity of the articles included in this review do not provide sufficient evidence to establish these relations. While this review does not suggest that all substances have the same effect, its results do indicate that psychedelics—perhaps with the exception of ketamine (as there were insufficient qualitative data)–may induce states of consciousness that are considered valuable by patients, suggesting a broad applicability of different psychedelics for mental disorders. More research is needed to substantiate this claim, or to establish whether some substances are indeed more qualified for the treatment of specific disorders. Third, it is possible that respondents’ favorable reports of their psychedelic treatments, when contrasted with previous (unsuccessful) conventional treatments, may be attributed to selection or expectation bias. Indeed, a substantial proportion of participants reported prior experience with psychedelics; this ranged from 10% with LSD [12] to 23% with ecstasy (MDMA) [7], and 25% [20], 55% [13] and 67% [4] reported prior experience with psilocybin. None of the studies on ibogaine and ketamine reported on this; all studies on ayahuasca, where reported, included participants who had undergone between one and 30 ceremonies. Additionally, in various studies, patients were self-selected, meaning they may not be representative for the larger population in seeking out these novel treatment modalities. Lastly, it is possible that research in this field, as in any new (or reappearing) research topic, overvalues positive aspects of these treatments [123]. Patient selection in pioneer studies is often (unintentionally) biased towards positive outcomes, and study samples are still small and non-generalizable. More studies in larger and more heterogeneous patient samples would be needed to appraise the real impact and ecological validity of these treatments.

The advent of psychedelic treatments has recently been labeled a new paradigm for psychiatry [124]. Patients frequently report on clinical effects beyond their psychiatric diagnosis, and pharmacologically distinct substances appear to exert comparable therapeutic processes for the same mental disorders. Psychedelic treatments may well contribute to a new sort of non-specific ‘precision medicines’ [125] or ‘targeted psychotherapies’ of mental disorders, by setting in motion subjective therapeutic processes that address root causes or core elements of a single psychopathology dimension (also called p-factor [126]) that manifest differently as different mental disorders. Since it is not well understood how psychotherapies contribute to change [127], it remains important to study these complexities more closely.

5 Conclusions

Treatments for mental disorders involving psychedelics are receiving renewed attention and scrutiny. The therapeutic mediators and mechanisms through which these compounds contribute to treatment outcomes remain insufficiently understood. Our review revealed several connected therapeutic processes—seen across substances and for different disorders—that contributed to clinically significant and personally meaningful outcomes. Exploring patient experiences can increase our understanding of underlying therapeutic mechanisms and processes, the role of (extra)pharmacological factors in these treatment modalities, which may contribute to optimizing treatment context, and lead to improved clinical responses and personal benefits. Despite the heterogeneity of substance, setting, and population, these studies also suggest that, in addition to a shared phenomenology, psychedelic treatments exhibit similar therapeutic processes and result in comparable outcomes. As this review demonstrates, qualitative research of psychedelic treatments can contribute to distinguishing specific features of these compounds, and show potential for elucidating otherwise undiscovered implications for the treatment of distinct mental disorders.

References

Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PCR, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(3):289–99.

Dakwar E, Nunes EV, Hart CL, Hu MC, Foltin RW, Levin FR. A sub-set of psychoactive effects may be critical to the behavioral impact of ketamine on cocaine use disorder: results from a randomized, controlled laboratory study. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:270–6.

Krupitsky EM, Grinenko AY. Ketamine psychedelic therapy (KPT): a review of the results of ten years of research. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1997;29(2):165–83.

Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Cosimano MP, Griffiths RR. Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(11):983–92.

Oehen P, Traber R, Widmer V, Schnyder U. A randomized, controlled pilot study of MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine)-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of resistant, chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(1):40–52.

Bouso JC, Doblin R, Farré M, Alcázar MA, Gómez-Jarabo G. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy using low doses in a small sample of women with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40(3):225–36.

Ot’alora GM, Grigsby J, Poulter B, Van Derveer JW, Giron SG, Jerome L, et al. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized phase 2 controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(12):1295–307.

Mithoefer MC, Wagner MT, Mithoefer AT, Jerome L, Doblin R. The safety and efficacy of ± 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine- assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(4):439–52.

Mithoefer MC, Wagner MT, Mithoefer AT, Jerome L, Martin SF, Yazar-Klosinski B, et al. Durability of improvement in post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and absence of harmful effects or drug dependency after 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy: a prospective long-term follow-up study. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27(1):28–39.

Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, Jerome L, Wagner M, Wymer J, et al. 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):486–97.

Grob CS, Danforth AL, Chopra GS, Hagerty M, McKay CR, Halberstadt AL, et al. Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):71–8.

Gasser P, Holstein D, Michel Y, Doblin R, Yazar-Klosinski B, Passie T, et al. Safety and efficacy of lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(7):513–20.

Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165–80.

Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, Umbricht A, Richards WA, Richards BD, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181–97.

Danforth AL, Grob CS, Struble CM, Feduccia AA, Walker N, Jerome L, et al. Reduction in social anxiety after MDMA-assisted psychotherapy with autistic adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235(11):3137–48.

Moreno FA, Wiegand CB, Taitano EK, Delgado PL. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin in 9 patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(11):1735–40.

Palhano-Fontes F, Barreto D, Onias H, Andrade KC, Novaes MM, Pessoa JA, et al. Rapid antidepressant effects of the psychedelic ayahuasca in treatment-resistant depression: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2019;49(4):655–63.

dos Santos RG, Sanches RF, de Osorio FL, Hallak JEC. Long-term effects of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression: a 5-year qualitative follow-up. Arch Clin Psychiatry (São Paulo). 2018;45(1):22–4.

Sanches RF, De Lima Osório F, Santos RGD, Macedo LRH, Maia-De-Oliveira JP, Wichert-Ana L, et al. Antidepressant effects of a single dose of ayahuasca in patients with recurrent depression a SPECT study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36(1):77–81.

Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Rucker J, Day CMJ, Erritzoe D, Kaelen M, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(7):619–27.

Han Y, Chen J, Zou D, Zheng P, Li Q, Wang H, et al. Efficacy of ketamine in the rapid treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2859–67.

Kishimoto T, Chawla JM, Hagi K, Zarate CA Jr, Kane JM, Bauer M, et al. Single-dose infusion ketamine and non-ketamine N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists for unipolar and bipolar depression: a meta-analysis of efficacy, safety and time trajectories. Psychol Med. 2016;46(7):1459–72.

Wilkinson ST, Katz RB, Toprak M, Webler R, Ostroff RB, Sanacora G. Acute and longer-term outcomes using ketamine as a clinical treatment at the Yale psychiatric hospital. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(4):17m11731.

Nichols DE. Hallucinogens. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;101(2):131–81.

Nichols DE. Psychedelics. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68(2):264–355.

Vollenweider FX, Kometer M. The neurobiology of psychedelic drugs: implications for the treatment of mood disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(9):642–51.

Mathai DS, Meyer MJ, Storch EA, Kosten TR. The relationship between subjective effects induced by a single dose of ketamine and treatment response in patients with major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;264:123–9.

Krediet E, Bostoen T, Breeksema J, van Schagen A, Passie T, Vermetten E. Reviewing the potential of psychedelics for the treatment of PTSD. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;23(6):385–400.

Roseman L, Nutt DJ, Carhart-Harris RL. Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Front Pharmacol. 2018;8(974):974.

Carhart-Harris RL, Roseman L, Haijen E, Erritzoe D, Watts R, Branchi I, et al. Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):725–31.

Rucker JJH, Jelen LA, Flynn S, Frowde KD, Young AH. Psychedelics in the treatment of unipolar mood disorders: a systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1220–9.

dos Santos RG, Osório FL, Crippa JAS, Riba J, Zuardi AW, Hallak JEC. Antidepressive, anxiolytic, and antiaddictive effects of ayahuasca, psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD): a systematic review of clinical trials published in the last 25 years. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(3):193–213.

Johnson MW, Richards WA, Griffiths RR. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(6):603–20.

Leary T, Lithwin GH, Metzner R. Reactions to psilocybin administered in a supportive environment. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1963;137:561–73.

Hartogsohn I. Constructing drug effects: a history of set and setting. Drug Sci Policy Law. 2017;3:1–17.

Hartogsohn I. Set and setting, psychedelics and the placebo response: an extra-pharmacological perspective on psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1259–67.

Majic T, Schmidt TT, Gallinat J. Peak experiences and the afterglow phenomenon: when and how do therapeutic effects of hallucinogens depend on psychedelic experiences? J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(3):241–53.

Kaelen M. The psychological and human brain effects of music in combination with psychedelic drugs, Thesis. London: Imperial College London; 2017. https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/handle/10044/1/55900.

Mithoefer MC, Doblin R, Mithoefer A, Jerome L, Ruse J, Gibson E, et al. A manual for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Santa Cruz: MAPS; 2013.

Labate BC, Cavnar C, editors. Therapeutic use of ayahuasca. Berlin: Springer; 2014.

Alper KR, Lotsof HS, Kaplan CD. The ibogaine medical subculture. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;115(1):9–24.

Brown TK. Ibogaine in the treatment of substance dependence. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2013;6(1):3–16.

Noller GE, Frampton CM, Yazar-klosinski B. Ibogaine treatment outcomes for opioid dependence from a twelve-month follow-up observational study. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(1):37–46.

Sanacora G, Frye MA, McDonald W, Mathew SJ, Turner MS, Schatzberg AF, et al. A consensus statement on the use of ketamine in the treatment of mood disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):399–405.

Wagner MT, Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, MacAulay RK, Jerome L, Yazar-Klosinski B, et al. Therapeutic effect of increased openness: investigating mechanism of action in MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31(8):967–74.

Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, MacLean K, Kaelen M, Nutt DJ, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368–78.

MacLean KA, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(11):1453–61.

Carhart-Harris RL, Murphy K, Leech R, Erritzoe D, Wall MB, Ferguson B, et al. The effects of acutely administered 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine on spontaneous brain function in healthy volunteers measured with arterial spin labeling and blood oxygen level-dependent resting state functional connectivity. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78(8):554–62.

Carhart-Harris RL, Kaelen M, Whalley MG, Bolstridge M, Feilding A, Nutt DJ. LSD enhances suggestibility in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 2014;232(4):785–94.

Hartogsohn I. The meaning-enhancing properties of psychedelics and their mediator role in psychedelic therapy, spirituality, and creativity. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:129.

Bogenschutz MP, Pommy JM. Therapeutic mechanisms of classic hallucinogens in the treatment of addictions: from indirect evidence to testable hypotheses. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(7–8):543–55.

Carhart-Harris RL, Erritzoe D, Haijen E, Kaelen M, Watts R. Psychedelics and connectedness. Psychopharmacology. 2017;235(2):547–50.

Watts R, Day C, Krzanowski J, Nutt D, Carhart-Harris R. Patients’ accounts of increased “Connectedness” and “Acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Humanist Psychol. 2017;57(5):520–64.

Watts R, Luoma JB. The use of the psychological flexibility model to support psychedelic assisted therapy. J Context Behav Sci. 2020;15:92–102.

Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, Kaelen M, Watts R, Carhart-Harris R. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076–87.

Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Richards WA, Richards BD, McCann U, Jesse R. Psilocybin occasioned mystical-type experiences: immediate and persisting dose-related effects. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218(4):649–65.

Griffiths RR, Richards WA, Johnson MW, McCann UD, Jesse R. Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(6):621–32.

Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Potential therapeutic effects of psilocybin. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(3):734–40.

Hendricks PS. Awe: a putative mechanism underlying the effects of classic psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):331–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1474185.

Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2013.

Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications; 2009.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;62:1006–12.

Stern BC, Jordan Z. Developing the review question and inclusion criteria. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(4):53–6.

Niemeijer AR. Exploring good care with surveillance technology in residential care for vulnerable people [PhD thesis]. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; 2015.

Barnett-page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research : a critical review. London; 2009 (NCRM Working Paper Series). Report No. 01/09. http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=188%0AESRC.

Noyes J, Booth A, Flemming K, Garside R, Harden A, Lewin S, Pantoja T, Hannes K, Cargo M, Thomas J. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series—paper 3: methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018(97):49–58.

Butler A, Hall RNH, Copnell B. A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016;13(3):241–9.

Carroll C, Booth A. Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Res Synth Methods. 2015;6(2):149–54.

Garside R. Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how? Innovation. 2014;27(1):67–79.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(45):1–10.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Lockwood C, Porritt K, Munn Z, Rittenmeyer L, Salmond S, Bjerrum M, et al. Chapter 2: Systematic reviews of qualitative evidence. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist. 2018. p. 1–6. [cited 12 May 2020]. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

Greer G, Tolbert R. Subjective reports of the effects of MDMA in a clinical setting. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1986;18(4):319–27.

Bogenschutz MP, Podrebarac SK, Duane JH, Amegadzie SS, Malone TC, Owens LT, et al. Clinical interpretations of patient experience in a trial of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for alcohol use disorder. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9(100):1–7.

Malone TC, Mennenga SE, Guss J, Podrebarac SK, Owens LT, Bossis AP, et al. Individual Experiences in Four Cancer Patients Following Psilocybin-Assisted Psychotherapy. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9(256):1–6.

Nielson EM, May DG, Forcehimes AA, Bogenschutz MP. The psychedelic debriefing in alcohol dependence treatment: illustrating key change phenomena through qualitative content analysis of clinical sessions. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9(132):1–13.

Schenberg EE, de Castro Comis MA, Alexandre JFM, Rasmussen Chaves BD, Tófoli LF, da Silveira DX. Treating drug dependence with the aid of ibogaine: a qualitative study. J Psychedelic Stud. 2017;1(1):10–9.

Schenberg EE, de Castro Comis MA, Alexandre JFM, Tófoli LF, Rasmussen Chaves BD, da Silveira DX. A phenomenological analysis of the subjective experience elicited by ibogaine in the context of a drug dependence treatment. J Psychedelic Stud. 2017;1(2):1–10.

Barone W, Beck J, Mitsunaga-Whitten M, Perl P. Perceived benefits of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy beyond symptom reduction: qualitative follow-up study of a clinical trial for individuals with treatment-resistant PTSD. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2019;51(2):199–208.

Swift TC, Belser AB, Agin-Liebes G, Devenot NN, Terrana S, Friedman HL, et al. Cancer at the dinner table: experiences of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for the treatment of cancer-related distress. J Humanist Psychol. 2017;57(5):488–519.

Belser AB, Agin-Liebes G, Swift TC, Terrana S, Devenot N, Friedman HL, et al. Patient experiences of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. J Humanist Psychol. 2017;57(4):354–88.

Noorani T, Garcia-Romeu A, Swift TC, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psychedelic therapy for smoking cessation: qualitative analysis of participant accounts. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):756–69.

van Schalkwyk GI, Wilkinson ST, Davidson L, Silverman WK, van Sanacora GGIS, et al. Acute psychoactive effects of intravenous ketamine during treatment of mood disorders: analysis of the Clinician Administered Dissociative State Scale. J Affect Disord. 2017;227:6–11.

Gasser P, Kirchner K, Passie T. LSD-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with a life-threatening disease: a qualitative study of acute and sustained subjective effects. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(1):57–68.

Camlin TJ, Eulert D, Thomas Horvath A, Bucky SF, Barsuglia JP, Polanco M. A phenomenological investigation into the lived experience of ibogaine and its potential to treat opioid use disorders. J Psychedelic Stud. 2018;2(1):24–35.

Lafrance A, Loizaga-Velder A, Fletcher J, Renelli M, Files N, Tupper KW, et al. Nourishing the spirit: exploratory research on ayahuasca experiences along the continuum of recovery from eating disorders. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(5):427–35.

Renelli M, Fletcher J, Tupper KW, Files N, Loizaga-Velder A, Lafrance A. An exploratory study of experiences with conventional eating disorder treatment and ceremonial ayahuasca for the healing of eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord. 2020;25(2):437–44.

Talin P, Sanabria E. Ayahuasca’s entwined efficacy: an ethnographic study of ritual healing from ‘addiction’. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;44:23–30.

Loizaga-Velder A, Verres R. Therapeutic effects of ritual ayahuasca use in the treatment of substance dependence: qualitative results. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46(1):63–72.

Watts R, Day C, Krzanowski J, Nutt D, Carhart-Harris R. Patients’ accounts of increased “connectedness” and “acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Hum Psychol. 2017;57(5):520–64.

Liu Y, Lin D, Wu B, Zhou W. Ketamine abuse potential and use disorder. Brain Res Bull. 2016;126:68–73.

Morgan CJA, Curran HV. Ketamine use: a review. Addiction. 2011;107:27–38.

Winkelman MJ. Psychedelics as medicines for substance abuse rehabilitation: evaluating treatments with LSD, peyote, ibogaine and ayahuasca. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2014;7(2):101–16.

Maj M. “Psychiatric comorbidity”: an artefact of current diagnostic systems? Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:182–4.

The Brainstorm Consortium. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018;360(6395):eaap8757.

Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine D, Quinn K, et al. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry Online. 2010;167(7):748–51.

Kendell R, Jablensky A. Distinguishing between the validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:4–12.

Jablensky A. Psychiatric classifications: validity and utility. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(1):26–31.

Kendler KS. The phenomenology of major depression and the representativeness and nature of DSM criteria. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(8):771–80.

Smoller JW, Andreassen OA, Edenberg HJ, Faraone SV, Glatt SJ, Kendler KS. Psychiatric genetics and the structure of psychopathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(3):409–20.

Krupitsky E, Kolp E, Winkelman MJ, Roberts TB. Ketamine psychedelic psychotherapy. In: Winkelman MJ, Roberts TB, editors. Psychedelic medicine: new evidence for hallucinogenic substances as treatments, vol. 2. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group; 2007. p. 67–85.

Veen C, Jacobs G, Philippens I, Vermetten E. Subanesthetic dose ketamine in posttraumatic stress disorder: a role for reconsolidation during trauma-focused psychotherapy? In: Vermetten E, Baker DG, Risbrough VB, editors. Behavioral neurobiology of PTSD. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 137–62.

Dakwar E, Nunes EV, Hart CL, Foltin RW, Mathew SJ, Carpenter KM, et al. A single ketamine infusion combined with mindfulness-based behavioral modification to treat cocaine dependence: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(11):923–30.

Barrett FS, Preller KH, Kaelen M. Psychedelics and music: neuroscience and therapeutic implications. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2018;30(4):350–62.

Kaelen M, Giribaldi B, Raine J, Evans L, Timmermann C, Rodriguez N, et al. The hidden therapist: evidence for a central role of music in psychedelic therapy. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235(2):505–19.

Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3(1):1–27.

Pahnke WN. The psychedelic mystical experience in the human encounter with death. Psychedelic Rev. 1970;11(1):3–20.

Richards WA, Rhead JC, Dileo FB, Yensen R, Kurland AA. The peak experience variable in DPT-assisted psychotherapy with cancer patients. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1977;9(1):1–10.

Grof S, Goodman LE, Richards WA, Kurland AA. LSD-assisted psychotherapy in patients with terminal cancer. Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 1973;8(3):129–44.

Dakwar E, Anerella C, Hart CL, Levin FR, Mathew SJ, Nunes EV. Therapeutic infusions of ketamine: do the psychoactive effects matter? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;136(1):153–7.

Garcia-Romeu A, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical experiences in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2014;7(3):157–64.

Preller KH, Vollenweider FX. Phenomenology, structure, and dynamic of psychedelic states. In: Halberstadt AL, Vollenweider FX, Nichols DE, editors. current topics in behavioral neurosciences behavioral neurobiology of psychedelic drugs. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag GmbH; 2018. p. 221–56.

Barrett FS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Neuroticism is associated with challenging experiences with psilocybin mushrooms. Pers Individ Dif. 2017;117:155–60.

Barrett FS, Bradstreet MP, Leoutsakos J-MS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. The challenging experience questionnaire: characterization of challenging experiences with psilocybin mushrooms. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1279–95.

Carbonaro TM, Bradstreet MP, Barrett FS, MacLean KA, Jesse R, Johnson MW, et al. Survey study of challenging experiences after ingesting psilocybin mushrooms: acute and enduring positive and negative consequences. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1268–78.