Abstract

Background and Objective

Inebilizumab is a humanized, affinity-optimized, afucosylated immunoglobulin (Ig)-G1κ monoclonal antibody that binds to CD19, resulting in effective depletion of peripheral B cells. It is being developed to treat various autoimmune diseases, including neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD), systemic sclerosis (SSc), and relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS).

Methods

Pharmacokinetic data from a pivotal study in adult subjects with NMOSD and two early-stage studies in subjects with SSc or relapsing MS were pooled and simultaneously analyzed using a population approach.

Results

Upon intravenous administration, the pharmacokinetics of inebilizumab were adequately described by a two-compartment model with parallel first-order and time-dependent nonlinear elimination pathways. An asymptotic nonlinear elimination suggests that inebilizumab undergoes receptor (CD19)-mediated clearance. The estimated systemic clearance (CL) of the first-order elimination pathway (0.188 L/day) and the volume of distribution (Vd) (5.52 L) were typical for therapeutic immunoglobulins. The elimination half-life was approximately 18 days. The maximum velocity (Vmax) of the nonlinear elimination pathway decreased with time, presumably due to the depletion of B cells upon inebilizumab administration. As for other therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, the CL and Vd of inebilizumab increased with body weight.

Conclusions

The presence of antidrug antibodies, status of hepatic or renal function, and use of small-molecule drugs commonly used by subjects with NMOSD had no clinically relevant impact on the pharmacokinetics of inebilizumab. The nonlinear elimination pathway at the 300 mg therapeutic dose level is not considered clinically relevant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Inebilizumab is a humanized, immunoglobulin G1κ monoclonal antibody that binds to CD19, resulting in effective depletion of peripheral B cells. |

The pharmacokinetics of inebilizumab were adequately described by a two-compartment model with parallel first-order and time-dependent nonlinear elimination pathways. |

Common covariates had no clinically relevant impact on the pharmacokinetics of inebilizumab. |

1 Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a rare, chronic, autoimmune, inflammatory disorder of the central nervous system predominately characterized by attacks of optic neuritis and longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Once thought to be a variant of multiple sclerosis (MS), NMOSD is now recognized as a distinct disease [1]. An important feature of NMOSD is the presence of serum autoantibodies against aquaporin-4 (AQP4) [2]. Pathogenic AQP4-immunoglobulin G (IgG) can be produced by a subpopulation of CD19-positive (CD19+) CD20-negative (CD20−) B cells showing morphological and phenotypical properties of plasmablasts, which are selectively increased in the peripheral blood of patients with NMOSD [3].

Inebilizumab is a humanized, affinity-optimized, afucosylated IgG1κ monoclonal antibody (mAb) that binds to the B-cell-specific surface antigen CD19, resulting in the depletion of B cells, including plasmablasts and some plasma cells. In a multicenter, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled pivotal phase II/III study (NCT02200770) in adult subjects with NMOSD, inebilizumab 300 mg administered on days 1 and 15 reduced the risk of an NMOSD attack (hazard ratio 0.272; p < 0.0001) [4].

Pharmacokinetic data of inebilizumab from this pivotal study in adult subjects with NMOSD and two early-stage studies in subjects with systemic sclerosis (SSc) and relapsing-remitting MS were pooled and simultaneously analyzed using a population approach. The aims of this investigation were to characterize the pharmacokinetics of inebilizumab and to evaluate the potential effects of demographic/pathological covariates and concomitant medication usage on the pharmacokinetic exposure.

2 Methods

2.1 Ethics Approval

All clinical study protocols and patient consent documents were reviewed by the local institutional review board (IRB), and written IRB approvals were obtained prior to each study’s initiation.

All clinical studies were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles described in the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Conference on Harmonisation guidance for good clinical practice, any applicable regulatory requirements, and any condition required by a regulatory authority and/or IRB.

2.2 Study Population

Two phase I clinical studies were conducted: one in adult subjects with SSc (NCT00946699) and another in adult subjects with MS (NCT01585766). A pivotal phase II/III study was conducted in adult subjects with NMOSD (NCT02200770).

2.3 Dosing and Sampling Schedule

Adult subjects received either intravenous or subcutaneous inebilizumab. In phase I studies, inebilizumab 0.1–10 mg/kg or 30–600 mg was administered by intravenous infusion. Six subjects with MS received single subcutaneous doses of 60 or 300 mg. In the phase II/III study, adult subjects with NMOSD received two intravenous infusions on days 1 and 15 of inebilizumab 300 mg or placebo. Table 1 lists the study designs, number of patients, and pharmacokinetic sampling schedules.

2.4 Bioanalysis

Serum concentrations of inebilizumab were determined using a validated colorimetric sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The quantitative range of the assay was 100.05 ng/mL (lower limit of quantitation [LLOQ]) to 4105.26 ng/mL in neat serum. Values below the LLOQ were reported as below the assay lower limit of quantitation (BLQ) values.

2.5 Pharmacokinetic Data Analysis

2.5.1 Data Handling and Exclusions

The pharmacokinetic and demographic covariate data from each study were formatted into derived population analysis datasets using validated SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) [5]. Pharmacokinetic data from subjects receiving placebo were excluded from the analysis. In addition, pharmacokinetic observations for which the serum concentration values were missing were excluded. Any quantifiable concentration values before the first dosing were ignored. Serum inebilizumab concentrations recorded as BLQ were retained in the dataset but excluded from data analysis if the BLQ observations represented < 10% of the overall data [6]. Outliers based on the population pharmacokinetic model analysis (a posteriori outliers) were evaluated using conditional weighted residuals and individual weighted residuals during the population pharmacokinetic model development [7].

2.5.2 Data Analysis Plan

A pharmacometric data analysis plan was executed prior to the conduct of the modeling according to regulatory guidance from the US FDA [25] and the European Medicines Agency [26]. The population pharmacokinetic analysis proceeded in stages: (1) an exploratory analysis to identify potential outliers and to select the structure model, (2) development of a base pharmacokinetic model, (3) covariate analysis, and (4) evaluation of the final model via goodness-of-fit plots and visual predictive check (VPC).

2.5.3 Modeling Methodology

Population model development and simulation were performed using nonlinear mixed-effects modeling (NONMEM; version 7.3; ICON Development Solutions, Hanover, MD, USA) [7]. The planned method of estimating parameters was the first-order conditional estimation with interaction. The package Xpose 4.4.0 [8] and the toolbox Perl-speaks-NONMEM (PsN) version 3.4.2 [9] were used for diagnostic plotting, VPC, and bootstrapping.

Model development was mainly based on the following criteria: (1) convergence and successful minimization of NONMEM objective function value (OFV), (2) standard goodness-of-fit plots, (3) OFV reductions in hierarchical models, (4) reductions in interindividual and residual variability or improved parameter estimate precision, (5) acceptable shrinkage in estimated parameters, and (6) a condition number less than 1000 (ratio of the largest to smallest eigenvalue of correlation matrix of estimate).

2.5.4 Population Pharmacokinetic Model

A two-compartment model with first-order elimination from the central compartment was initially utilized to describe the pharmacokinetics of inebilizumab following intravenous administration. The model was parameterized using systemic clearance (CL), central distribution volume (Vc), intercompartmental clearance (Q), and peripheral distribution volume (Vp) (Fig. 1). A CD19 target-mediated elimination pathway and potential time-dependency of CL or the asymptotic nonlinear elimination were subsequently evaluated during the base model development.

Pharmacokinetic model of intravenously administered inebilizumab. CL clearance, Kdec first-order rate constant describing the decrease of Vmax over time, Km concentration to achieve half of Vmax, Q intercompartmental clearance, Vc volume of distribution in the central compartment, Vmax maximum velocity of Michaelis–Menten equation, Vp volume of distribution in the peripheral compartment

Interindividual variabilities (IIV) were assumed to be log-normally distributed, where θi is the value of a parameter θ for the ith individual, θTV represents the central tendency estimate or typical value of pharmacokinetic parameter θ in the population, and ηθ, i is the subject-specific random effect explaining the difference between the ith individual and the population; ηθ, i is assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of zero and a variance of ωθ2(i.e., \(\eta_{\theta ,i} \sim N\left( {0,\omega_{{\text{P}}}^{{2}} } \right)\)).

Residual unexplained variability is explained by a combined proportional and additive error model:

where C(t)ij is the observed and Ĉ(t)ij is the model-predicted serum concentration for sample j of individual i, and \(\varepsilon_{pij}\) and \(\varepsilon_{aij}\) are assumed normally distributed proportional and additive residual random errors with mean of zero and estimated variance of \(\sigma_{1}^{2}\) and \(\sigma_{2}^{2}\), respectively.

2.5.5 Covariate Analysis

The final model was developed by incorporating the effect of relevant covariates on key structural model parameters of the base model. The covariate selection was based on clinical judgment, mechanistic plausibility, and prior knowledge.

The relationship between a continuous covariate and a pharmacokinetic parameter was modeled using power functions (Eq. 3) with the covariate normalized to the population median for the dataset. The categorical covariates were modeled using fractional change functions (Eq. 4):

In Eq. (3), θ1 represents the typical value of a pharmacokinetic parameter (P) for the median individual (median covariate) and θ2 represents the coefficient for particular covariate effect. In Eq. (4), θ1 represents the typical value of a pharmacokinetic parameter (P) for the individuals with the most common realization of Factor (Factor = 0) in the analysis dataset, and θ2 represents the fractional change from θ1 in pharmacokinetic parameter P for an individual with the least common realization of Factor (Factor = 1).

Statistical tests of covariate–parameter relationships were assessed with the likelihood-ratio test by forward inclusion, followed by backward elimination. Only covariate effects with strong effect (p < 0.001; ΔOFV > 10.83 with 1 degree of freedom [df]) on inebilizumab pharmacokinetics were retained in the final model.

2.5.6 Finalization of Population Pharmacokinetic Model

The goodness-of-fit plots were assessed to evaluate the performance of the final pharmacokinetic model. Diagnostic plots were generated to evaluate the adequacy of the overall goodness-of-fit and stated model assumptions. The uncertainty of parameter estimates of the final model were also evaluated by bootstrapping in addition to the standard errors estimated from NONMEM. The median and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of bootstrapping estimates for the inebilizumab pharmacokinetic parameters were compared with the final model pharmacokinetic parameter estimates for the robustness of the final pharmacokinetic model. The predictive performance of the developed final model was evaluated using the VPC method.

3 Results

3.1 Data Summary

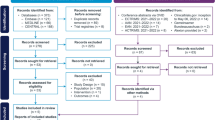

A total of 1848 pharmacokinetic observations were available from 219 inebilizumab-treated subjects. Six subjects with MS who received a single subcutaneous administration of inebilizumab were initially excluded from the population pharmacokinetic analysis because of the small sample size and lack of clinical relevance. The population pharmacokinetic dataset of intravenously administered inebilizumab contained 1626 quantifiable pharmacokinetic samples from 213 subjects. Among these, nine quantifiable concentrations were excluded from the population analysis (eight observations from eight subjects with NMOSD were associated with the open-label extension period of the study; one concentration in a subject with NMOSD was 28-fold higher than previous observation, without any corresponding dosing record). Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the baseline categorical and continuous variables, and Table 3 summarizes the pathological covariates for subjects with NMOSD in the pivotal phase II/III study.

3.2 Structure Pharmacokinetic Model Development

Table 4 presents key steps in the development of the inebilizumab population pharmacokinetic model. Body weight was included as a covariate in the structural model for all pharmacokinetic parameters of the linear two-compartment model, because body weight has been proven to be a significant covariate on pharmacokinetic parameters for the majority of IgG-based mAbs [10]. Inclusion of a nonlinear elimination pathway, parameterized using an asymptotic Michaelis–Menten equation, significantly improved the overall fit of the data (model 2, ∆OFV = − 124).

The saturable elimination pathway suggests that inebilizumab undergoes receptor (CD19)-mediated clearance. Because the total target amount (CD19) in subjects is expected to reduce after treatment of inebilizumab, the target-mediated drug clearance may decrease over time, resulting in time-varying pharmacokinetics. Indeed, an empirical time function to account for the reduction of the maximum velocity (Vmax) of the nonlinear elimination pathway (CLNL) with time lowered the OFV by 23.9 (model 3, Table 4). Figure 1 shows the pharmacokinetic model structure of inebilizumab.

The differential equation system describing the pharmacokinetic model is as follows:

where Ac and Ap are the free drug amounts in the central and peripheral compartments, respectively, TDVM represents the time-dependent maximum capacity of the saturable clearance, and Kdec represents a first-order rate constant, describing the decrease of Vmax over time.

A similar model was previously developed to describe the time-dependent reduction in clearance of rituximab over time, presumably due to the shrinkage of the CD20 antigen pool during the treatment period [11]. In this model, there is a time-dependent nonlinear clearance (CLNL) in addition to the first-order clearance CL (Eq. 9):

where CLNL0 represents the initial nonlinear clearance at time 0, and KD is an empirical decaying rate constant of CLNL with time. With the two additional pharmacokinetic parameters, CLNL and KD, the OFV was reduced by 8.6 (model 4, Table 4), much less than the time-dependent Michaelis–Menten clearance approach (models 2 and 3, Table 4).

3.3 Covariate Analysis

As body weight typically influences the clearance and volume of distribution of therapeutic mAbs, the effect of body weight was incorporated in the inebilizumab base pharmacokinetic model (model 3, Table 4). A correlation matrix plot of candidate covariates with respect to the interindividual variability (η) of structure parameters of the base model was used for covariate screening. Study effect on estimation of Vmax was the only candidate that had a moderate correlation (r = 0.5) [12]. Subsequent likelihood-ratio tests revealed that the Vmax of the clinical study in subjects with SSc was much greater than that of studies in subjects with MS and NMOSD (model 5, ∆OFV = − 50.7). Each study enrolled subjects with different types of disease, confounding the interpretation of the study effect on Vmax.

The correlation of antidrug antibody (ADA) status with CL was weak (r = 0.2; Table 5 and Fig. 2). In fact, the inclusion of the effect of time-varying ADA status on CL slightly increased the OFV (model 6, ∆OFV = 0.466). None of the liver function or liver damage markers (total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase [ALP], or aspartate aminotransferase [AST]) showed any correlation with inebilizumab CL. There was no correlation between creatinine clearance or estimated glomerular filtration rate and the CL of inebilizumab. Most frequently used concomitant medications, baseline pathophysiological covariates (AQP4-IgG serostatus, Expanded Disability Status Scale score, number of prior NMOSD attacks, disease duration), age, sex, and race had no significant effect on inebilizumab CL.

The correlation among IIVs in the final covariate model was examined graphically using matrix plots. Both CL and Vmax contributed to the elimination of inebilizumab. Inclusion of covariance of IIV between CL and Vmax using the $BLOCK option of NONMEM did not improve data fitting (model 7, ∆OFV = − 0.049), although the correlation between CL and Vmax decreased from 0.399 to 0.184.

Table 6 summarizes the estimated structure and variance parameters of the final pharmacokinetic model (model 5). The estimated clearance of the first-order elimination pathway (188 mL/day) was close to the clearance of nonspecific endogenous IgG, and the volume of distribution of central compartment (2.95 L) approached the plasma volume. The estimated Km, corresponding to half of the Vmax of the saturable nonlinear elimination pathway, was 5.89 µg/mL.

The relative standard errors (RSEs) of the key pharmacokinetic parameters were all less than 10% except Km (25.5%). The study-dependent Vmax (higher Vmax of study in subjects with SSc) was also precisely estimated with < 20% RSE. On the other hand, to describe the time-dependent change in Vmax, the first-order rate constant Kdec was estimated with a relatively high uncertainty of 55% RSE.

The precision of the final intravenous pharmacokinetic model was also evaluated by bootstrapping the pharmacokinetic dataset 1000 times. The distributions of the parameter estimates (Fig. 3) showed that the parameter point estimates from the observed data were similar to those from the bootstrapped data. The 95% CI of each parameter estimate obtained from bootstrapping is also presented in the model evaluation in Table 5.

Distributions of parameter estimates via bootstrapping (model 5). The red line indicates the original estimates from model 5, the vertical black line indicates the median of 1000 bootstrapped samples. The values of SIGMA.1.1 and VMAXSTUDY1102 were not estimated. The effect of study 1102 on Vmax was evaluated by pooling with the pharmacokinetic data from study 1155. Kdec was estimated by division with 1000 (e.g., the value of 3 in the Kdec plot corresponds to estimated Kdec of 0.003 1/day). CL clearance, IIV interindividual variability, Kdec first-order rate constant for decrease in Vmax, Km concentration to achieve half of Vmax, prop.err proportional error, Q intercompartmental clearance, Vc volume of distribution in the central compartment, Vmax maximum velocity of the saturable clearance process Vp volume of distribution in the peripheral compartment, WT body weight

Figure 4 shows the standard goodness-of-fit plots of the final intravenous pharmacokinetic model (model 5). The plots of random effects (ETA) versus nominal doses were used to assess whether the nonlinear pharmacokinetics were sufficiently addressed by the pharmacokinetic model. The ETA distributions were reasonably well distributed around zero value regardless of the nominal doses, suggesting that the nonlinearity in the pharmacokinetics was adequately captured by the final Michaelis–Menten model. The diagnostic plots of weighted residuals (Fig. 5) also supported that the proportional residual error model in the final pharmacokinetic model was sufficient in the description of the pharmacokinetic data.

Standard goodness-of-fit plots of final intravenous pharmacokinetic model. “Observations” are inebilizumab concentrations. “Population predictions” are the concentrations predicted for individual’s observations based on typical (population) values of the pharmacokinetic parameters, whereas “individual predictions” are the concentrations predicted for individual’s observations based on individual values of pharmacokinetic parameters. All the concentrations are in µg/mL unit. The circles are the pairs of observations and predictions or weighted residuals. The solid red lines are loess smoothing lines. |iWRES| absolute individual weighted residuals

In addition, the final intravenous pharmacokinetic model (model 5) was evaluated using prediction-corrected VPC [13]. The final pharmacokinetic model was used to simulate the 1000 replicated VPC datasets. Figure 6 shows the performance of the final intravenous pharmacokinetic model in subjects with NMOSD. The 95 percentile intervals across replicates were compared with corresponding summary statistics derived from observed data. The model predicted distribution overlap with the observed concentration well, indicating that the final intravenous pharmacokinetic model characterized the observed pharmacokinetics adequately. Figure 7 presents the VPC plots of all subjects, including those with SSc and MS.

Prediction-corrected visual predictive check plot (linear and log scale, model 5). The blue circles represent the observed concentration. The solid and dashed lines represent the median and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the observations. The shaded red and blue areas represent the 95% confidence interval of the median and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles predicted by the model, respectively

Visual predictive check plot of NMOSD study (linear and log scales, model 5). The blue circles represent the observed concentration. The solid and dashed lines represent the median and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the observations. The shaded red and blue areas represent the 95% confidence interval of the median and 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles predicted by the model, respectively

3.4 Pharmacokinetics of Subcutaneously Administered Inebilizumab

The pharmacokinetics of subcutaneously administered inebilizumab have not been evaluated in subjects with NMOSD. Among 219 subjects in the population pharmacokinetic dataset, only six subjects with MS received a single subcutaneous injection of inebilizumab (three subjects each at 60 and 300 mg). Upon completion of the final intravenous pharmacokinetic model, the initially excluded pharmacokinetic data from these six subjects with MS were combined with the intravenous pharmacokinetic data and modeled for characterization of the absorption of subcutaneously administered inebilizumab. The estimated absorption half-life was 4.1 days, and the estimated absolute bioavailability was 81%. However, because of the small sample size, further information is required for proper evaluation of the absorption of inebilizumab from a subcutaneous injection site.

4 Discussion

Inebilizumab is a humanized, afucosylated IgG1κ mAb against the B-cell-specific surface antigen CD19. The removal of fucose from the Fc region results in approximately tenfold increased affinity for the activating Fc gamma receptor IIIA and significantly enhances natural killer cell-mediated depletion of B cells via antibody-dependent cellular toxicity and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis mechanisms [14, 15]. In adults with SSc, MS, or NMOSD, treatment with inebilizumab effectively depleted peripheral B cells by > 99%. In subjects with NMOSD who received intravenous inebilizumab 300 mg on day 1 and day 15 during the 28-week randomized controlled period, the risk of NMOSD attack was significantly lower than in those receiving placebo [4]. Inebilizumab treatment also led to significant reductions of Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) worsening from baseline, cumulative total active magnetic resonance imaging lesions, and number of NMOSD-related in-patient hospitalizations. [4]

The pharmacokinetics of inebilizumab were evaluated in two phase I studies in subjects with SSc or MS and a pivotal phase II/III study in subjects with NMOSD. The weight-based (mg/kg) dosing method was used in the first-in-human study in subjects with SSc, whereas fixed doses (milligrams) were administered to subjects with MS and NMOSD. Except the six subjects with MS who received a single subcutaneous administration, all other 213 subjects in these three studies received inebilizumab via intravenous infusion(s). To fully characterize the pharmacokinetic properties of inebilizumab and to assess the clinical relevance of demographic/pathological covariate effects, pharmacokinetic data from these clinical studies were pooled for a population meta-analysis.

Prior analysis of data from phase I studies using the noncompartmental method indicated more than dose-proportional increases in pharmacokinetic exposure. When the drug concentration greatly exceeds the target level and binding affinity, the Michaelis–Menten approach reasonably describes the asymptotic, target-mediated drug clearance typically observed for mAbs against cell-membrane-associated receptors [16]. Inebilizumab is an affinity-optimized IgG that binds to and depletes CD19-expressing B cells. During population pharmacokinetic model development, the inclusion of a nonlinear elimination pathway (Michaelis–Menten parameterization) significantly improved the overall fit of the data (model 2, ∆OFV = − 123.7 with 2 df). Furthermore, as B cells greatly depleted upon inebilizumab administration, an empirical first-order decay function was added to the Vmax of the nonlinear elimination pathway to account for the shrinking target antigen pool (model 3, ∆OFV = − 23.9 with 2 df). A similar approach of having a time-dependent clearance for the nonlinear elimination pathway was previously used to describe the pharmacokinetics of rituximab, a chimeric IgG against CD20, in subjects with chronic lymphocytic leukemia [17] or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [11]. This approach was evaluated for inebilizumab (model 4) but was inferior to the Michaelis–Menten approach with time-dependent Vmax (model 3).

As for other therapeutic antibodies [20,21,22,23,24], body weight influences the clearance and distribution of inebilizumab. The effects of body weight were incorporated in the model during base model development. Although the default allometric exponents of body weight on clearance and volume terms are 0.75 and 1, respectively, fixing the exponents to such default values substantially increased OFV (model 1a, Table 4). Except body weight, the only covariate influencing the pharmacokinetics of inebilizumab were study CP200 on Vmax. The estimate of Vmax in subjects with SSc was 2.1-fold higher than in subjects with MS or NMOSD (model 5, ∆OFV = − 50.7 with 1 df), even though the baseline B-cell count in subjects with SSc was somewhat lower than in those with MS or NMOSD (Table 2). Furthermore, no correlation was found for baseline B-cell count and Vmax (r < 0.01). Each study enrolled subjects with different types of diseases, which confounds the interpretation of the effect on Vmax. Nevertheless, at the therapeutic dose level, when the nonlinear target-mediated elimination pathway is saturated, the difference in Vmax is not expected to be clinically relevant.

Inebilizumab is primarily eliminated through the reticuloendothelial system by the widely expressed proteolytic enzyme. In the final pharmacokinetic model (model 5, Table 4), the estimated typical CL for a 66-kg adult was 188 mL/day. Distribution of mAbs is usually restricted to extracellular fluid. The estimated Vc and Vp for inebilizumab was 2.95 L and 2.57 L, respectively, typical for therapeutic IgG. At the therapeutic dose level, when the nonlinear pathway is saturated, the elimination half-life of inebilizumab is approximately 18 days.

The estimated Vmax and Km of the nonlinear elimination pathway were 832 µg/day (MS and NMOSD) and 5.89 µg/mL, respectively, corresponding to a maximum nonlinear clearance of 141 mL/day when inebilizumab concentration is much lower than Km. Likely associated with the depletion of B cells, including plasmablasts and some plasma cells upon inebilizumab administration, Vmax decreases with time, with an estimated half-life of 236 days. At the end of the 28-week randomized controlled period, Vmax in subjects with NMOSD decreased to 56% of the original value.

Although the CL of inebilizumab in ADA-positive subjects appeared higher than that in ADA-negative subjects, population analysis showed no statistically significant effect of the presence of ADA on CL. Since mAbs are not primarily cleared via the hepatic pathway, change in hepatic function is not expected to influence inebilizumab CL. None of the liver function or liver damage markers (total bilirubin, ALP, AST) showed any correlation with CL. Given the large molecular weight and hydrodynamic size of an mAb, inebilizumab is not expected to be filtered through the glomerulus. There was no correlation between creatinine clearance or estimated glomerular filtration rate and CL of inebilizumab. Further assessments demonstrated similar CL of inebilizumab in subjects with both normal and impaired hepatic or renal function. Similarly, inebilizumab pharmacokinetics were not influenced by the baseline pathophysiological covariates AQP4-IgG serostatus, EDSS, number of prior NMOSD attacks, or disease duration. Furthermore, age, sex, and race had no significant effect on inebilizumab CL.

Cytochrome P450 enzymes, efflux pumps, and protein-binding mechanisms are not involved in the clearance of inebilizumab, a humanized IgG1κ mAb. The potential risk of pharmacokinetic interactions between inebilizumab and other drugs is low. Based on the population pharmacokinetic analysis, small-molecule drugs commonly used by subjects with NMOSD (paracetamol, diphenhydramine, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone) had no effect on inebilizumab pharmacokinetics. However, as with other B-cell-depleting drugs (rituximab [18], ocrelizumab [19]), concomitant usage of inebilizumab and other immunosuppressant drugs may result in an increased risk of infection.

Given the orphan disease indication, inebilizumab was evaluated in one pivotal study, in which only one dose level (300 mg) was tested. The population pharmacokinetic modeling relied on the pooled data from early studies in subjects with SSc or MS. Furthermore, the small sample size (n = 6) of subjects with MS receiving subcutaneous administration of inebilizumab meant we could not reliably estimate the absolute subcutaneous bioavailability.

5 Conclusion

Pharmacokinetic data of inebilizumab from early-stage studies in patients with SSc or MS and a phase II/III study in adult subjects with NMOSD were pooled and analyzed using a population approach. Inebilizumab pharmacokinetics were described by a two-compartment model with parallel first-order and asymptotic nonlinear elimination pathways. The Vmax of the target-mediated elimination pathway decreased with time, likely because of the depletion of B cells upon inebilizumab administration. The estimated disposition parameter values of inebilizumab were typical for a human IgG. The presence of ADA, age, sex, race, hepatic and renal function markers, baseline CD20+ B-cell count, baseline NMOSD-related pathological variables, and commonly used small-molecule drugs had no impact on inebilizumab pharmacokinetics.

References

Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(9):810–5.

Jarius S, Wildemann B. AQP4 antibodies in neuromyelitis optica: diagnostic and pathogenetic relevance. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(7):383–92.

Chihara N, Aranami T, Sato W, Miyazaki Y, Miyake S, Okamoto T, et al. Interleukin 6 signaling promotes anti-aquaporin 4 autoantibody production from plasmablasts in neuromyelitis optica. Nat Acad Sci USA. 2010;108(9):3701–6.

Cree BAC, Bennett J, Kim HJ, Weinshenker BG, Pittock SJ, Wingerchuk DM, et al. Inebilizumab for the treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (N-MOmentum): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1352–63.

SAS Software version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, United States. 2020.

Byon W, Smith MK, Chan P, Tortorici MA, Riley S, Dai H, et al. Establishing best practices and guidance in population modeling: an experience with an internal population pharmacokinetic analysis guidance. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2013;2(7):e51.

Beal S, Boeckmann A, Bauer R, Sheiner LB. NONMEM User's Guides. (1989–2009) Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA. 2009

Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO (1999) Xpose—an S-PLUS based population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model building aid for NONMEM. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 58(1):51–64

Lindbom L, Ribbing J, Jonsson EN. Perl-speaks-NONMEM (PsN)–a Perl module for NONMEM related programming. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2004;75(2):85–94.

Yan L, Wang B, Chia YL, Roskos LK. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of benralizumab in adult and adolescent patients with asthma. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58:943–58.

Rozman S, Grabnar I, Novaković S, Mrhar A, Jezeršek NB. Population pharmacokinetics of rituximab in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and association with clinical outcome. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:1782–90.

Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(5):1763–8.

Bergstrand M, Hooker AC, Wallin JE, Karlsson MO. Prediction-corrected visual predictive checks for diagnosing nonlinear mixed-effects models. AAPS J. 2011;13(2):143–51.

Herbst R, Wang Y, Gallagher S, Mittereder N, Kuta E, et al. B-cell depletion in vitro and in vivo with an afucosylated anti-CD19 antibody. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335(1):213–22.

Gallagher S, Turman S, Yusuf I, Akhgar A, Wu Y, et al. Pharmacological profile of MEDI-551, a novel anti-CD19 antibody, in human CD19 transgenic mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2016;36:205–12.

Yan X, Mager DE, Krzyzanski W. Selection between Michaelis-Menten and target-mediated drug disposition pharmacokinetic models. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2010;37(1):25–47.

Li J, Zhi J, Wenger M, Valente N, Dmoszynska A, Robak T, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of rituximab in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52(12):1918–26.

Rituximab [package insert]. San Francisco, CA: Biogen Idec Inc. and Genentech, Inc.; 2012.

Ocrelizumab [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genetech, Inc.; 2020.

Wang B, Arends R, Roskos LK. A preliminary population pharmacokinetic analysis of panitumumab, a fully human IgG2 anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody. AAPS J. 2004;6(1):2375.

Baverel PG, Jain M, Stelmach I, She D, Agoram B, Sandbach S, et al. Pharmacokinetics of tralokinumab in adolescents with asthma: implications for future dosing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(6):1337–49.

Oh CK, Faggioni R, Jin F, Roskos LK, Wang B, Birrell C, et al. An open-label, single-dose bioavailability study of the pharmacokinetics of CAT-354 after subcutaneous and intravenous administration in healthy males. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69(6):645–55.

Wang B, Wu CY, Jin D, Vicini P, Roskos L. Model-based discovery and development of biopharmaceuticals: a case study of mavrilimumab, DModel based discovery and development of biopharmaceuticals: a case study of mavrilimumab. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2018;7(1):5–15.

Zheng Y, Narwal R, Jin C, Baverel PG, Jin X, Gupta A, et al. Population modeling of tumor kinetics and overall survival to identify prognostic and predictive biomarkers of efficacy for durvalumab in patients with urothelial carcinoma. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2018;103(4):643–52.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: population pharmacokinetics. Rockville, MD: US FDA; 1999.

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on reporting the results of population pharmacokinetic analyses. London: EMA. 2007. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/reporting-results-population-pharmacokinetic-analyses.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Ben Mitchell, PhD; Kamille O’Connor, BS, PMP; and Ryan Criste, PharmD, of Amador Bioscience (Pleasanton, CA, USA), for clinical data programming and preparation and submission of this manuscript. The research was funded by Viela Bio.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This analysis was funded by Viela Bio.

Conflicts of interest

Li Yan, Daniel Cimbora, Eliezer Katz and William A. Rees are employees of Viela Bio. Holly Kimko and Bing Wang received financial assistance from Viela Bio.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data and material that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Some data may not be made available because of privacy or ethical restrictions.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

LY and BW wrote the manuscript. EK, WAR, DC and LY designed the research. LY, HK, BW, WAR, EK and DC interpreted the data. HK, BW and LY analyzed the data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, L., Kimko, H., Wang, B. et al. Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Inebilizumab in Subjects with Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders, Systemic Sclerosis, or Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. Clin Pharmacokinet 61, 387–400 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-021-01071-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-021-01071-5