Abstract

Background and Objective

Whether benefits and risks of intravenous (IV) infliximab combotherapy with immunosuppressants versus infliximab monotherapy apply to subcutaneous (SC) infliximab is unknown. This post hoc analysis of a pivotal randomised CT-P13 SC 1.6 trial aimed to compare SC infliximab monotherapy with combotherapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Methods

Biologic-naïve patients with active Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis received CT-P13 IV 5 mg/kg at Week (W) 0 and 2 (dose-loading phase). At W6, patients were randomised (1:1) to receive CT-P13 SC 120 or 240 mg (patients < 80 or ≥ 80 kg) every 2 weeks until W54 (maintenance phase), or to continue CT-P13 IV every 8 weeks until switching to CT-P13 SC from W30. The primary endpoint—non-inferiority of trough serum concentrations—was assessed at W22. We report a post hoc analysis comparing pharmacokinetic, efficacy, safety and immunogenicity outcomes up to W54 for patients randomised to CT-P13 SC, stratified by concomitant immunosuppressant use.

Results

Sixty-six patients were randomised to CT-P13 SC (37 monotherapy, 29 combotherapy). At W54, there were no significant differences in the proportions of patients achieving target exposure (5 µg/mL; 96.6% monotherapy vs 95.8% combotherapy; p > 0.999) or meeting efficacy or biomarker outcomes including clinical remission (62.9% vs 74.1%; p = 0.418). Monotherapy and combotherapy groups had comparable immunogenicity (anti-drug antibodies [ADAs]: 65.5% vs 48.0% [p = 0.271], neutralising antibodies [in ADA-positive patients]: 10.5% vs 16.7% [p = 0.630], respectively).

Conclusions

Pharmacokinetics, efficacy and immunogenicity were potentially comparable between SC infliximab monotherapy and combotherapy in biologic-naïve IBD patients.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02883452.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intravenous infliximab combination with immunosuppressants (combotherapy) is more efficacious than monotherapy for biologic-naïve inflammatory bowel disease patients, but it is not known whether this applies to subcutaneous (SC) infliximab treatment. |

Clinical outcomes—comprising pharmacokinetics, efficacy and immunogenicity—were comparable with SC infliximab monotherapy and combotherapy in tumour necrosis factor inhibitor-naïve patients with inflammatory bowel disease. |

If corroborated by larger studies, this analysis could be regarded as initial evidence that SC infliximab combotherapy is not superior to SC infliximab monotherapy, paving the way to use potentially safer monotherapy treatment options for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. |

1 Introduction

The tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) infliximab is recommended in guidelines for first- or second-line biologic therapy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which comprises Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [1,2,3,4]. Although the prescribing information for reference infliximab does not contain specific recommendations on the concomitant use of immunosuppressants when treating patients with CD or UC [5, 6], infliximab may be used in combination with immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, or methotrexate [7, 8], in line with treatment guidelines [1,2,3,4]. Meta-analyses of clinical trial data and studies of real-life cohorts of patients with IBD have yielded conflicting results as to whether combotherapy with intravenous (IV) infliximab and an immunosuppressant offers clinical benefits in terms of efficacy compared with IV infliximab monotherapy [9,10,11,12,13]. However, in immunosuppressant- and biologic-/TNFi-naïve patients with moderate to severe CD or UC, randomised controlled trials and cohort studies have shown that initiating combotherapy is associated with improved outcomes, when compared with IV infliximab monotherapy [14,15,16,17], with the benefits of combotherapy related to increased serum infliximab levels [18]. In addition, combotherapy is associated with protection from developing immunogenicity to IV infliximab [17].

Subcutaneous (SC) CT-P13 (CT-P13 SC) is the first SC infliximab product to receive regulatory approval in Europe, which was initially obtained for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis [19, 20]. Regulatory approval was later extended to other rheumatic diseases and IBD indications on the basis of the pivotal randomised controlled CT-P13 SC 1.6 study (NCT02883452), which compared CT-P13 SC and CT-P13 IV treatment in patients with active CD or UC [21, 22]. Part 2 of this study demonstrated pharmacokinetic non-inferiority of CT-P13 SC to CT-P13 IV, and suggested comparability of efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity profiles between treatment arms [22]. CT-P13 SC also offered potential pharmacokinetic benefits compared with CT-P13 IV, with trough serum concentrations (Ctrough) relatively stable and consistently maintained above the generally accepted target exposure [22]. Consequently, SC infliximab has been perceived by an expert panel as a biobetter based on the potential clinical benefits over IV infliximab, particularly in terms of pharmacokinetics [23]. Subcutaneous infliximab was also shown to elicit similar, if not potentially slightly diminished, immunogenicity compared with IV infliximab [24, 25].

Whether the advantages of combining an immunosuppressant with IV infliximab are also true for combotherapy with SC infliximab and immunosuppressants has not hitherto been addressed. Therefore, we conducted a post hoc analysis to compare the efficacy of SC infliximab monotherapy versus combotherapy with immunosuppressants, using data from the pivotal trial.

2 Methods

The primary study was conducted according to International Council for Harmonisation guidelines and following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and all applicable national, state, and local laws [22]. The protocol and written study materials were approved by institutional review boards/independent ethics committees prior to study initiation [22]. All patients provided written informed consent [22]. Individual participant data are not available to be shared. The original study was pre-registered (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02883452) but this post hoc analysis was not.

Patients were enrolled in this open-label, randomised, multicentre, parallel-group Phase 1 study at 50 sites in 15 countries, as previously reported [22]. Full eligibility criteria have been reported; briefly, biologic-naïve patients (aged 18–75 years) with active CD or UC, who had a disease duration of ≥ 3 months and had not responded to an adequate course of conventional therapy, were enrolled in the study [22]. Patients received CT-P13 IV 5 mg/kg at Weeks 0 and 2 (dose-loading phase), and were then randomised (1:1) at Week 6 (maintenance phase) to continue therapy with CT-P13 IV every 8 weeks (until Week 30 when patients switched to receive CT-P13 SC) or CT-P13 SC 120 mg (patients weighing < 80 kg) or 240 mg (patients weighing ≥ 80 kg) every 2 weeks from Weeks 6 to 54 (Fig. 1) [22]. Randomisation was stratified by use of immunosuppressant treatment (yes vs no), disease type (UC vs CD), clinical response at Week 6 (yes vs no), and body weight at Week 6 (< 80 kg vs ≥ 80 kg) [22]. Patients could receive concomitant immunosuppressants provided the dose remained unchanged throughout the study and had been stable for ≥ 8 weeks (thiopurines) or ≥ 6 weeks (methotrexate) prior to first infliximab administration [22].

Patient disposition, updated from Schreiber et al [22]. aBased on body weight at Week 6, patients received CT-P13 SC 120 mg Q2W (for patients weighing < 80 kg) or CT-P13 SC 240 mg Q2W (for patients weighing ≥ 80 kg). CD Crohn’s disease, IV intravenous, SC subcutaneous, Q2W every 2 weeks, UC ulcerative colitis

The primary endpoint of the original study was non-inferiority of Ctrough of CT-P13 at Week 22 for CT-P13 SC versus CT-P13 IV; this has been previously reported [22]. The present post hoc analysis included only patients who received CT-P13 SC from Week 6 onwards and compared pharmacokinetic, efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity endpoints up to Week 54 for patients who received CT-P13 SC alone (monotherapy group) versus patients who received CT-P13 SC in combination with immunosuppressants (combotherapy group). For pharmacokinetic assessment, infliximab pre-dose concentration at all study visits was measured using Meso Scale Discovery electrochemiluminescence (Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC, Rockville, MD, USA) [22, 26]. Bioanalytical methods were validated according to European Medicines Agency guidelines and assay performance for the measurement of infliximab was appropriately demonstrated [19]. The therapeutic target exposure of 5 µg/mL (as suggested by the American Gastroenterological Association) [27] was defined as an exploratory endpoint [22]. Efficacy assessments were performed prior to infliximab treatment at all study visits (other than the pharmacokinetic monitoring visit) and included Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score for patients with CD and partial Mayo score for patients with UC [22]. Colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy were performed at screening, Week 22, and Week 54 (or the end-of-study visit), and scored for Simplified Endoscopic Activity Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) in patients with CD or for Mayo endoscopic sub-score in patients with UC [22]. For patients with CD, CDAI-100 response was defined as a decrease in CDAI score of ≥ 100 points from baseline [22]. For patients with UC, partial Mayo response was defined as a decrease in partial Mayo score of ≥ 2 points compared with baseline, plus a decrease in the sub-score for rectal bleeding of ≥ 1 point, or an absolute sub-score for rectal bleeding of 0 or 1 [22]. In this analysis, mucosal healing in patients with CD was defined as achieving adjusted endoscopic remission by SES-CD, with an absolute overall SES-CD score of ≤ 2 points in patients who had confirmed mucosal abnormalities (overall SES-CD score > 0) at baseline. For patients with UC, mucosal healing was defined as an absolute Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0 or 1 [22]. C-reactive protein (CRP) and faecal calprotectin (FC) levels were evaluated at all study visits (apart from the pharmacokinetic monitoring visit) [22]. Safety outcomes evaluated were the number of patients experiencing an injection-site reaction, infection, or malignancy, which may have occurred during either CT-P13 IV induction or CT-P13 SC maintenance therapy. Serum samples that were obtained pre-dose at each treatment visit (except at Week 2) were also analysed for immunogenicity (anti-drug antibodies [ADAs] and neutralising antibodies [NAbs]) using drug-tolerant electrochemiluminescence assays with affinity capture elution steps (Celltrion, Inc., Incheon, Republic of Korea) [22]. Anti-drug antibody concentrations ≥ 25 ng/mL were detectable in the presence of 120 µg/mL serum infliximab; NAb concentrations ≥ 1000 ng/mL were detectable with 40 µg/mL serum infliximab [22].

The sample size for the primary study endpoint has been previously described [22]. For this post hoc analysis, patients with available data at relevant time points were included in each analysis. For Week 54 clinical response and remission analyses (determined by CDAI and partial Mayo scores) and pharmacodynamic outcomes (FC and CRP), missing values for patients who had discontinued the study due to lack of/or insufficient efficacy or due to disease progression were imputed as non-responders. Statistical comparisons between monotherapy and combotherapy groups used the Fisher exact test for categorical variables or the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Differences are reported in a descriptive manner. Statistical analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

3 Results

3.1 Patients

Overall, 136 patients were enrolled in the study after screening between 27 March 2018 and 8 August 2018, with follow-up concluding on 17 January 2020 [22]. Sixty-six of these patients were randomised to receive CT-P13 SC from Week 6 onwards and were included in the current analysis, comprising 37 patients in the monotherapy group and 29 patients in the combotherapy group (Fig. 1). Other than concomitant immunosuppressant use, demographics and baseline disease characteristics were comparable between the monotherapy and combotherapy groups (Table 1). Most patients (96.6%) in the combotherapy group were receiving concomitant thiopurines at Week 6 (the inception of the current post hoc analysis); only one patient was receiving methotrexate.

3.2 Pharmacokinetics

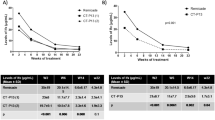

In both groups, mean pre-dose serum infliximab concentrations at or approaching peak values were reached at Week 2, with a slight decrease in concentrations observed at Week 6 (Fig. 2). For the remainder of the study period (from Week 14 to Week 54), mean pre-dose concentrations remained relatively consistent in both groups, within the bounds of 18.8 µg/mL to 23.7 µg/mL. Mean pre-dose concentrations exceeded the target exposure (5 μg/mL) throughout the study period (from Week 2 onwards), regardless of whether or not patients were receiving concomitant immunosuppressant therapy. Moreover, there was no significant difference between the monotherapy and combotherapy groups in terms of the proportion of patients with pre-dose concentration exceeding the target exposure at Week 54 (28/29 [96.6%] vs 23/24 [95.8%]; p > 0.999; Table 2).

Mean (95% CI) pre-dose concentration for CT-P13 SC up to Week 54. Patients with available data at the respective week were analysed. Concentrations below the lower limit of quantification before Week 0 were set to zero; other concentrations below the lower limit of quantification were set to the lower limit of quantification. CI confidence interval, IV intravenous, SC subcutaneous

3.3 Efficacy

There was no significant difference between the monotherapy and combotherapy groups in terms of clinical response rates at Week 54, assessed by CDAI-100 response and partial Mayo score for patients with CD and UC, respectively (p = 0.673 and p = 0.628, respectively; Table 2; Fig. S1a, b in the Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). There were no significant differences between groups in the proportions of patients achieving clinical remission (monotherapy: 22/35 [62.9%] vs 20/27 [74.1%]; p = 0.418; Table 2; Fig S1c in the ESM), mucosal healing (20/25 [80.0%] vs 16/22 [72.7%]; p = 0.732; Table 2; Fig. S1d), normal CRP levels (26/35 [74.3%] vs 22/27 [81.5%]; p = 0.555; Table 2; Fig. S1e), and normal FC levels (10/33 [30.3%] vs 5/24 [20.8%]; p = 0.547; Table 2; Fig. S1f) at Week 54.

Mean absolute values and changes from baseline in CDAI and partial Mayo scores were also comparable between monotherapy and combotherapy groups throughout the study (Fig. 3).

Efficacy outcomes up to Week 54. a Mean CDAI score, b CDAI change from baseline, c mean partial Mayo score, d partial Mayo score change from baseline. Patients with available data at the respective week were analysed. CDAI Crohn’s Disease Activity Index, CI confidence interval, IV intravenous, SC subcutaneous

3.4 Safety

There were no significant differences between the monotherapy and combotherapy groups in terms of the incidence of injection-site reactions (p = 0.555), infections (p = 0.607), or malignancy (p > 0.999) (Table 2). However, there were numerical differences between groups in the proportion of patients experiencing injection-site reactions (monotherapy: 7/37 [18.9%] vs combotherapy: 8/29 [27.6%]) and infection (12/37 [32.4%] vs 12/29 [41.4%]).

3.5 Immunogenicity

Despite the use of concomitant immunosuppressants in the combotherapy group, the incidence of immunogenicity did not differ between groups when assessed using a drug-tolerant assay (Table 2; Fig. S2 in the ESM). Specifically, the proportion of ADA-positive patients was 65.5% (19/29) in the monotherapy group and 48.0% (12/25) in the combotherapy group (p = 0.271). The proportion of NAb positivity among ADA-positive patients was 10.5% (2/19) in the monotherapy group and 16.7% (2/12) in the combotherapy group (p = 0.630).

4 Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of patients in the CT-P13 SC arm of Part 2 of the pivotal CT-P13 SC 1.6 study, pharmacokinetic, efficacy, and immunogenicity outcomes were comparable between patients with CD or UC who received either CT-P13 SC monotherapy or CT-P13 SC in combination with an immunosuppressant. To our knowledge, the present analysis provides the first insights into the potential clinical comparability of SC infliximab monotherapy and combotherapy with immunosuppressants.

Previous research has demonstrated that combotherapy with IV infliximab and an immunosuppressant can improve outcomes for immunosuppressant- and biologic-/TNFi-naïve patients with IBD, relative to infliximab monotherapy [12, 14,15,16,17]. However, some studies have reported that combotherapy may not improve clinical effectiveness compared with monotherapy [9,10,11], including specifically for patients who have had an inadequate response to immunosuppressant treatment [9, 10]. The association between higher infliximab Ctrough and combotherapy (vs IV infliximab monotherapy) is well established [17, 18, 28,29,30], although not all analyses have found differences in Ctrough values between patients receiving combotherapy and those receiving monotherapy [31]. There is also strong evidence, including from the PANTS study, for a link between combotherapy and reduced immunogenicity of IV infliximab [17, 18, 28, 30]. In turn, this is associated with an improved pharmacokinetic profile and efficacy outcomes [13, 18]. A post hoc analysis of the SONIC study showed that, among patients who achieved high trough drug levels with IV infliximab, there were no significant differences in efficacy outcomes between those who did and did not receive concomitant immunosuppressants [18]. Our current results are in line with and extend these observations by showing that the pharmacokinetic profile and higher pre-dose concentrations achieved with SC infliximab therapy (compared with IV infliximab [22, 23]) may potentially translate into comparable efficacy for SC infliximab-treated patients, regardless of whether they receive concomitant immunosuppressants [22, 23].

In our analysis, overall immunogenicity was comparable between groups. Specifically, rates of total ADAs were numerically higher in the monotherapy group versus the combotherapy group but were not significantly different. Moreover, the rate of NAb positivity, which is more instrumental in mediating clinically relevant immunogenicity [32] and can impact efficacy more directly [33, 34], was similar or even numerically lower in the monotherapy compared with the combotherapy group (6.9% vs 8.0% of the overall group, respectively). It may be hypothesised that the high and stable serum infliximab (antigen) concentrations mediated by SC infliximab administration inhibit the induction of ADAs through high-zone tolerance, or a favourable infliximab-to-TNF ratio may reduce the formation of immune complexes and, consequently, ADAs [22]. This may reduce immune activation towards the drug, thereby dampening production of high-affinity ADAs or NAbs [22, 34], resulting in the observed comparability of immunogenicity between groups, even when assessed using a drug-tolerant assay.

Although the modest cohort size and limited exposure time preclude firm conclusions about safety, SC infliximab monotherapy may conceivably be associated with reduced risks of infection and malignancy relative to combotherapy with immunosuppressants as was previously reported in studies considering the IV infliximab formulation [9, 35, 36]. While it is debatable whether TNFi monotherapy is associated with an increased risk of lymphoproliferative disease in patients with IBD [37], it will be important to collect further data on this topic in patients with IBD receiving infliximab SC monotherapy. In addition, monotherapy may offer additional advantages by reducing the pill burden that has been associated with non-adherence to treatments for IBD [38, 39]. Avoiding combotherapy with thiopurines may also lead to a reduced risk of developing severe COVID-19 [40], further incentivising to explore ways to optimise monotherapy strategies.

The current findings are limited by the exploratory nature of the post hoc analyses conducted and the modest sample size that may render it underpowered to detect small differences; as such, the findings should be interpreted with caution. In addition, since all but one patient included in the combotherapy group received a thiopurine, results may not be representative for patients receiving other immunosuppressants, such as methotrexate; while this is well aligned with immunosuppressant usage in routine clinical practice, future studies should aim to enrol more patients receiving methotrexate as a component of combotherapy. The generalisability of our findings to clinical practice could be impacted by the TNFi-naïve study population [22], as prior biologic exposure may be associated with reduced efficacy due to the development of immunogenicity [33]. Finally, while no histological outcomes were included in the present post hoc analysis, the endpoint definitions employed were consistent with those used in the primary analysis of the study [22]. Acknowledging these limitations, our study provides valuable initial insights into the pharmacokinetics, efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of CT-P13 SC monotherapy versus immunosuppressant combotherapy, opening up avenues for further investigation. However, larger comparative studies are warranted.

5 Conclusion

Subcutaneous infliximab monotherapy may provide comparable clinical efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and immunogenicity to combotherapy with immunosuppressants in TNFi-naïve patients with active CD or UC. Larger comparative studies are needed to confirm these observations.

References

Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV, Isaacs KL, Regueiro MD, Gerson LB, Sands BE. ACG clinical guideline: management of Crohn’s disease in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(4):481–517. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2018.27.

Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, Kucharzik T, Gisbert JP, Raine T, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn’s disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(1):4–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz180.

Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, Sauer BG, Long MD. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384–413. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000152.

Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, Karmiris K, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(7):769–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx009.

European Medicines Agency. Remicade: summary of product characteristics. 2022. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/remicade-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Mar 2022.

US Food and Drug Administration. Remicade prescribing information. 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/103772s5401lbl.pdf. Accessed 24 Mar 2022.

Duchesne C, Faure P, Kohler F, Pingannaud MP, Bonnaud G, Devulder F, et al. Management of inflammatory bowel disease in France: a nationwide survey among private gastroenterologists. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46(8):675–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2014.04.004.

Brady JE, Stott-Miller M, Mu G, Perera S. Treatment patterns and sequencing in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Ther. 2018;40(9):1509–21.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.07.013.

Osterman MT, Haynes K, Delzell E, Zhang J, Bewtra M, Brensinger CM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of immunomodulators with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(7):1293–301.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.017.

Jones JL, Kaplan GG, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Baidoo L, Devlin S, Melmed GY, et al. Effects of concomitant immunomodulator therapy on efficacy and safety of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(13):2233–40.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.06.034.

Lichtenstein GR, Diamond RH, Wagner CL, Fasanmade AA, Olson AD, Marano CW, et al. Clinical trial: benefits and risks of immunomodulators and maintenance infliximab for IBD-subgroup analyses across four randomized trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30(3):210–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04027.x.

Sokol H, Seksik P, Carrat F, Nion-Larmurier I, Vienne A, Beaugerie L, et al. Usefulness of co-treatment with immunomodulators in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with scheduled infliximab maintenance therapy. Gut. 2010;59(10):1363–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.212712.

Ungar B, Chowers Y, Yavzori M, Picard O, Fudim E, Har-Noy O, et al. The temporal evolution of antidrug antibodies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with infliximab. Gut. 2014;63(8):1258–64. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305259.

Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(15):1383–95. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0904492.

Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rutgeerts P, Tang KL, et al. Randomised clinical trial: deep remission in biologic and immunomodulator naïve patients with Crohn’s disease—a SONIC post hoc analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(8):734–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13139.

Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, Márquez JR, Scott BB, Flint L, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(2):392–400.e3. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.052.

Kennedy NA, Heap GA, Green HD, Hamilton B, Bewshea C, Walker GJ, et al. Predictors of anti-TNF treatment failure in anti-TNF-naive patients with active luminal Crohn’s disease: a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(5):341–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-1253(19)30012-3.

Colombel JF, Adedokun OJ, Gasink C, Gao LL, Cornillie FJ, D’Haens GR, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine improves infliximab pharmacokinetic features and efficacy: a post hoc analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(8):1525–32.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.09.033.

European Medicines Agency. Remsima: assessment report on extension(s) of marketing authorisation. 2019. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/remsima-h-c-2576-x-0062-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Mar 2022.

BusinessWire. Celltrion Healthcare receives EU marketing authorisation for world’s first subcutaneous formulation of infliximab, Remsima SC™, for the treatment of people with rheumatoid arthritis. 2019. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20191125005867/en/Celltrion-Healthcare-receives-EU-marketing-authorisation-for-world%E2%80%99s-first-subcutaneous-formulation-of-infliximab-Remsima-SC%E2%84%A2-for-the-treatment-of-people-with-rheumatoid-arthritis. Accessed 24 Mar 2022.

European Medicines Agency. Remsima: extension of indication variation assessment report. 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/variation-report/remsima-h-c-2576-ii-0082-epar-assessment-report-variation_en.pdf. Accessed 24 Mar 2022.

Schreiber S, Ben-Horin S, Leszczyszyn J, Dudkowiak R, Lahat A, Gawdis-Wojnarska B, et al. Randomized controlled trial: subcutaneous vs intravenous infliximab CT-P13 maintenance in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(7):2340–53. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.02.068.

D’Amico F, Solitano V, Aletaha D, Hart A, Magro F, Selmi C, et al. Biobetters in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory disorders: an international Delphi consensus. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20(7):102849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102849.

Kim H, Alten R, Cummings F, Danese S, D’Haens G, Emery P, et al. Innovative approaches to biologic development on the trail of CT-P13: biosimilars, value-added medicines, and biobetters. MAbs. 2021;13(1):1868078. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2020.1868078.

Ben-Horin S, Reinisch W, Ye BD, Westhovens R, Yoo DH, Lee SJ, et al. OP234—development of a subcutaneous formulation of CT-P13 (infliximab): maintenance subcutaneous administration may elicit lower immunogenicity compared to intravenous treatment. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(8S):A90–1.

Stefura WP, Graham C, Lotoski L, HayGlass KT. Improved methods for quantifying human chemokine and cytokine biomarker responses: ultrasensitive ELISA and Meso Scale electrochemiluminescence assays. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;2020:91–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-9591-2_7.

Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S, Gerson L, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute guideline on therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(3):827–34. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.032.

Drobne D, Bossuyt P, Breynaert C, Cattaert T, Vande Casteele N, Compernolle G, et al. Withdrawal of immunomodulators after co-treatment does not reduce trough level of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(3):514–21.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.027.

Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Adedokun OJ, et al. Factors associated with short- and long-term outcomes of therapy for Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(3):539–47.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2014.09.031.

Chi LY, Zitomersky NL, Liu E, Tollefson S, Bender-Stern J, Naik S, et al. The impact of combination therapy on infliximab levels and antibodies in children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(6):1344–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izy010.

Razanskaite V, Bettey M, Downey L, Wright J, Callaghan J, Rush M, et al. Biosimilar infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: outcomes of a managed switching programme. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(6):690–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw216.

El Amrani M, Gobel C, Egas AC, Nierkens S, Hack CE, Huitema ADR, et al. Quantification of neutralizing anti-drug antibodies and their neutralizing capacity using competitive displacement and tandem mass spectrometry: infliximab as proof of principle. J Transl Autoimmun. 2019;1:100004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtauto.2019.100004.

Vermeire S, Gils A, Accossato P, Lula S, Marren A. Immunogenicity of biologics in inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756283X17750355. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756283X17750355.

Atiqi S, Hooijberg F, Loeff FC, Rispens T, Wolbink GJ. Immunogenicity of TNF-inhibitors. Front Immunol. 2020;11:312. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00312.

Lemaitre M, Kirchgesner J, Rudnichi A, Carrat F, Zureik M, Carbonnel F, et al. Association between use of thiopurines or tumor necrosis factor antagonists alone or in combination and risk of lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1679–86. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.16071.

Kirchgesner J, Lemaitre M, Carrat F, Zureik M, Carbonnel F, Dray-Spira R. Risk of serious and opportunistic infections associated with treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):337–46.e10. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.012.

Dahmus J, Rosario M, Clarke K. Risk of lymphoma associated with anti-TNF therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: implications for therapy. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2020;13:339–50. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEG.S237646.

Kane SV. Strategies to improve adherence and outcomes in patients with ulcerative colitis. Drugs. 2008;68(18):2601–9. https://doi.org/10.2165/0003495-200868180-00006.

Casellas F, Ginard D, Riestra S. Patient satisfaction in the management of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis: results of a Delphi study among patients and physicians. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48(10):1172–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2016.06.036.

Ungaro RC, Brenner EJ, Gearry RB, Kaplan GG, Kissous-Hunt M, Lewis JD, et al. Effect of IBD medications on COVID-19 outcomes: results from an international registry. Gut. 2021;70(4):725–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322539.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support, including development of article drafts in consultation with the authors, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking, and referencing, was provided by Beatrice Tyrrell, DPhil, CMPP, at Aspire Scientific Limited (Bollington, UK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This post hoc analysis was funded in full by Celltrion Healthcare Co., Ltd (Incheon, Republic of Korea). Medical writing support for this article was funded by Celltrion Healthcare Co., Ltd. Open access funding was provided by Celltrion Healthcare Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of interest

Geert D’Haens has served as a speaker for AbbVie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Galapagos, Immunic, Johnson and Johnson, and Pfizer; served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for AbbVie, Ablynx, Allergan, AstraZeneca, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline, and Seres Health; served as a consultant for AbbVie, Agomab, AM Pharma, AMT, Arena Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Exeliom Biosciences, Exo Biologics, Galapagos, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Gossamerbio, Immunic, Index Pharmaceuticals, Johnson and Johnson, Kaleido, Origo, Pfizer, Polpharma, Procise Diagnostics, Progenity, Prometheus Biosciences, Prometheus Laboratories, Protagonist, and Roche; and received grants or contracts from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Helmsley Foundation, Pfizer, and Takeda. Walter Reinisch has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from AbbVie, Celltrion, Falk Pharma, Ferring, Janssen, Medice, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, PLS Education, Roche, Shire, Takeda, Therakos, and Vifor; served as a consultant for AbbVie, Algernon, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bioclinica, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Calyx, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Ernst & Young, Falk Pharma, Ferring, Fresenius, Galapagos, Gatehouse Bio, Genentech, Gilead, Grünenthal, ICON, Index Pharma, Inova, Intrinsic Imaging, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Landos Biopharma, LivaNova, Mallinckrodt, Medahead, MedImmune, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD, Nash Pharmaceuticals, Nestle, Novartis, OMass, Otsuka, Parexel, Periconsulting, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, Prometheus, Protagonist, Provention, Quell Therapeutics, Robarts Clinical Trial, Roche, Sandoz, Schering-Plough, Second Genome, Seres Therapeutics, Setpoint Medical, Sigmoid, Sublimity, Takeda, Teva Pharma, Therakos, Theravance, Vifor, and Zealand; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from AbbVie, Janssen, and Takeda; and served on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or advisory board for OSE Pharma. Stefan Schreiber has served as a consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Bristol Myers Squibb, Biogen, Celltrion, Celgene, Falk, Ferring, Fresenius, Galapagos, Gilead, IMAB, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Pfizer, Protagonist, Provention Bio, Sandoz/Hexal, Takeda, Theravance, and UCB. Fraser Cummings has served as a consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Galapagos, Janssen, Samsung Bioepis, and Tillots; received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Dr Falk, Galapagos, Janssen, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, and Tillots; received support for attending meetings and/or travel from Janssen and Tillots; received grants for conducting investigator-initiated studies from Biogen, Celltrion, and Janssen; and is a member of the British Society of Gastroenterology IBD section (unpaid) and is the UK IBD registry clinical lead (paid). Peter M. Irving has served as a consultant for AbbVie and Bristol Myers Squibb; received lecture fees from AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Falk Pharma, Galapagos, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer, and Takeda; served on Data Safety Monitoring Boards or advisory boards for AbbVie, Arena, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Celltrion, Genentech, Gilead, Hospira, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Pfizer, Prometheus, Roche, Sandoz, Samsung Bioepis, and Takeda; and received financial support for research from Celltrion, Galapagos, Pfizer, and Takeda. Byong Duk Ye has served on advisory boards for AbbVie Korea, Celltrion, Daewoong Pharma, Ferring Korea, Janssen Korea, Organoid Sciences Ltd, Pfizer Korea, Takeda, and Takeda Korea; served as a consultant for Chong Kun Dang Pharm., CJ Red BIO, Daewoong Pharma, Kangstem Biotech, Korea Otsuka Pharm, Korea United Pharm. Inc., Medtronic Korea, NanoEntek, Organoid Sciences Ltd, and Takeda; received speaker fees from AbbVie Korea, Celltrion, Curacle, Ferring Korea, IQVIA, Janssen Korea, Pfizer Korea, Takeda, and Takeda Korea; and received research grants from Celltrion and Pfizer Korea. Dong-Hyeon Kim and SangWook Yoon are employees of and hold stock or stock options in Celltrion Healthcare Co., Ltd. Shomron Ben-Horin has served as a consultant or advisory board member for AbbVie, Celltrion, Falk, Ferring, Galmed, GSK, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Takeda; and received research support from AbbVie, Celltrion, Galmed, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material. The individual participant data cannot be shared publicly for the privacy of individuals.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

This post hoc analysis is based on the primary study (NCT02883452) that was conducted according to International Council for Harmonisation guidelines and following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and all applicable national, state, and local laws. The protocol and written study materials were approved by institutional review boards/independent ethics committees prior to study initiation.

Consent to Participate

All patients provided written informed consent.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

GD’H: Conceptualisation (lead), methodology (lead), supervision (lead), visualisation (equal), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—reviewing and editing (equal). WR: conceptualisation (equal), methodology (equal), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—reviewing and editing (equal). SS: conceptualisation (equal), methodology (equal), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—reviewing and editing (equal). FC: conceptualisation (equal), methodology (equal), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—reviewing and editing (equal). PMI: conceptualisation (equal), methodology (equal), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—reviewing and editing (equal). BDY: conceptualisation (equal), methodology (equal), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—reviewing and editing (equal). D-HK: conceptualisation (equal), formal analysis (lead), methodology (equal), validation (lead), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—reviewing and editing (equal). SWY: conceptualisation (equal), formal analysis (lead), methodology (equal), validation (lead), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—reviewing and editing (equal). SB-H: conceptualisation (lead), methodology (lead), supervision (lead), visualisation (equal), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—reviewing and editing (equal). All authors had access to the post hoc analysis data and contributed to manuscript drafting, critical review, and revision. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

D’Haens, G., Reinisch, W., Schreiber, S. et al. Subcutaneous Infliximab Monotherapy Versus Combination Therapy with Immunosuppressants in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomised Clinical Trial. Clin Drug Investig 43, 277–288 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-023-01252-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-023-01252-z