Abstract

Background

Despite the benefits offered by biosimilars in terms of cost savings and improved patient access to biological therapies, and an established regulatory pathway in Europe, biosimilar adoption is challenged by a lack of knowledge and understanding among stakeholders such as healthcare professionals and patients about biosimilars, impacting their trust and willingness to use them. In addition, stakeholders are faced with questions about clinical implementation aspects such as switching.

Objective

This study aims to provide recommendations on how to improve biosimilar understanding and adoption among stakeholders based on insights of healthcare professionals (physicians, hospital pharmacists, nurses), patient(s) (representatives) and regulators across Europe.

Method

The study consists of a structured literature review gathering original research data on stakeholder knowledge about biosimilars, followed by semi-structured interviews across five stakeholder groups including physicians, hospital pharmacists, nurses, patient(s) (representatives) and regulators across Europe.

Results

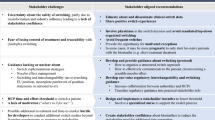

Although improvement in knowledge was observed over time, generally low to moderate levels of awareness, knowledge and trust towards biosimilars among healthcare professionals and patients are identified in literature (N studies = 106). Based on the provided insights from interviews with European experts (N = 44), a number of challenges regarding biosimilar stakeholder understanding are identified, including a lack of practical information about biosimilars and their use, a lack of understanding about biosimilar concepts and a lack of knowledge about biologicals in general. Misinformation by originator industry is also believed to have impacted stakeholder trust. In terms of possible solutions and actions to improve stakeholder understanding, broad support exists to (1) organize initiatives focussed on explaining the rationale behind biosimilar concepts and the approval pathway, (2) invest in education about biologicals in general, (3) develop clear and one-voice regulatory guidance about biosimilar interchangeability and switching across Europe, (4) disseminate real-world clinical biosimilar (switch) data, (5) share biosimilar experiences by key opinion leaders and among peers, (6) provide practical biosimilar product information, (7) provide guidance about biosimilar use, (8) actively counterbalance misinformation and organize information initiatives by neutral entities, (9) organize multi-stakeholder informational and educational efforts, aligning information between involved stakeholder groups and (10) design initiatives in a way that ensures active information uptake. Furthermore, interviewees argue that governments should be proactive in these regards.

Conclusions

This study argues in favour of a structural, multi-stakeholder framework at both European and national level to improve stakeholder biosimilar understanding and acceptance. It proposes a number of actionable recommendations that can inform policy making and guide stakeholders, which can contribute to realizing healthcare system benefits offered by biosimilar competition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Healthcare professionals and patients have shown low to moderate awareness, knowledge and trust towards biosimilars in previous research; this underlines the need for continued efforts to improve biosimilar understanding among stakeholders. |

This article proposes a structural, multi-stakeholder framework with actionable recommendations aimed at informing policymakers and guiding stakeholders to improve biosimilar understanding. |

A coordination of efforts between the different involved stakeholders is needed to capture the societal and patient benefits offered by biosimilars. |

1 Introduction

Following loss of exclusivity of original biological medicines, highly similar versions—biosimilars—can enter the market. Biosimilars are approved according to the same standards of quality, safety and efficacy as any biological and need to demonstrate that any differences to their reference product are not clinically meaningful [1]. Biosimilars can partly rely on data that have been gathered for the reference product, allowing tailoring of their clinical development, leading to lower development costs and subsequent prices [2]. Biosimilars pose a timely opportunity to relieve budgetary pressured healthcare systems, as the price competition introduced by biosimilars has been recognized to significantly impact overall medicine expenditure. Further, biosimilar market access has shown to increase patient access to these formerly expensive biological therapies [3, 4].

Since the establishment of a regulatory approval pathway in 2004 and the first biosimilar approval in 2006 in Europe [2], more than 55 biosimilars for 15 distinct reference products have been approved, accumulating to more than 15 years of regulatory and clinical experience with biosimilars [5]. Although the arrival of biosimilars has shown to provide benefits on a societal and patient level, so far biosimilar market shares have varied across European countries and products, and were in some cases limited. Gaps in knowledge and understanding about biosimilars and their regulatory approval process among healthcare professionals (HCPs) and patients may limit biosimilar acceptance and curb their use [6, 7].

In addition to improving stakeholder understanding, other measures may be needed to fully capture the potential of biosimilars, as uptake has also been challenged by discouraging procurement processes, lack of stakeholder motivation and stakeholder uncertainties about interchangeability and switching [6, 7].

This study, the first in a series of two, aims to provide recommendations on how to improve biosimilar understanding and acceptance based on a structured literature review and insights from expert interviewees (physicians, hospital pharmacists, nurses, patient[s] [representatives] and regulators) across Europe.

The second article in this series assesses multi-stakeholder insights on how to improve biosimilar use in clinical practice [8].

2 Methods

This study consists of a structured literature review and semi-structured interviews with expert stakeholders.

2.1 Structured Literature Review

A structured literature review was carried out to identify HCPs’ and patients’ knowledge about biosimilars. PubMed was searched up to the 4th of January 2020 by combining search terms on biosimilars, HCPs, patients and knowledge (see Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] 1). Search results were screened based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (see ESM 2). The inclusions were further supplemented by grey literature.

Original research studies describing the knowledge and understanding of HCPs or patients about biosimilars and biosimilar-related concepts were included. Articles describing expert opinions or position statements were excluded. Study parameters and results were systematically extracted.

2.2 Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews with experts were conducted across five stakeholder groups (physicians, hospital pharmacists, nurses, patients and regulators) to obtain multi-stakeholder insights on how to improve knowledge and understanding about biosimilars among HCPs and patients. Experts were recruited across Europe and where possible from European organizations or institutions (e.g. representatives of European stakeholder associations) to capture pan-European perspectives. HCPs and patients were recruited across disease domains currently relevant for biosimilars. Participants were identified by screening websites of stakeholder associations and regulatory authorities, conference speakers, authors of biosimilar literature and the research group’s network.

The interview questions were based on topics identified in the literature (see ESM 3). The interview questions were tested in three pilot interviews.

The interviews were carried out between October 2017 and June 2018. Interviews were conducted in English, with the exception of a few interviews in Dutch based on the interviewee’s preference. The interviews were conducted by Skype®, phone or in person and digitally audio-recorded. Participation was voluntary and interviewees did not receive any remuneration.

The recordings were transcribed ad verbatim. The transcripts were pseudonymized and analysed according to the thematic framework method using NVivo software® [9].

3 Results

3.1 Literature Review—Mapping Knowledge and Trust Levels of Healthcare Professionals and Patients

The screening and selection of 383 identified records led to the inclusion of 100 studies. Additionally, six studies were identified in grey literature, resulting in a total of 106 studies reporting original research on HCPs’ and/or patients’ biosimilar perceptions. With the exception of a few studies involving focus group discussions, interviews or expert panels, studies consisted of a survey. The perspectives of physicians and patients were surveyed the most (N = 37, 35% and N = 32, 30%, respectively, versus pharmacists: N = 10, 10%; nurses: N = 1, 1%; across stakeholder groups: N = 26, 25%). Approximately one third of the studies were either industry sponsored (N = 8, 8%) or conducted by industry (N = 28, 26%). The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Fig. 1.

Structured literature review—characteristics of studies on stakeholder knowledge and perceptions about biosimilars (N = 106). a Studies categorized per stakeholder group, b Studies categorized per region, c Studies categorized per therapeutic area, d Studies categorized per publication year, e Studies categorized per reported conflict of interest/funding type. A: no declared conflict of interest, B: declared author conflict of interest (or disclosure of interest) (e.g. HCPs/academics providing advice/paid consultancy to industry), C: industry sponsoring/educational grant from industry to support independent research declared, D: research conducted by industry/lobby organization/consultancy, E: potential funding/conflict of interest not specified, f Studies categorized per number of participants. Derm dermatology, Endocr endocrinology, Gastro-ent gastro-enterology, GP general practice, N number, Onco/hemato oncology, haematology, Rheum Rheumatology, ROW rest of the world, US United States

Although improvements were observed over time, gaps in knowledge and understanding about biosimilars and regulatory concepts were generally identified across regions, therapeutic areas and stakeholder groups. Overall, voiced concerns across studies included questions about biosimilar immunogenicity, safety, efficacy, interchangeability, (automatic) substitution and extrapolation of indications [6, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Various studies identified that, if presented with a choice, patients would object to being switched or physicians would object to switching their patients to a biosimilar [19, 20]. In contrast, patients who were switched generally reported a positive experience, suggesting that experience with biosimilars leads to increased trust [21, 22]. Additionally, concerns existed among stakeholders about being forced to switch or being limited in prescription choice [23,24,25,26].

In several studies, physicians showed willingness to use biosimilars if this would result in increased patient access to treatment or in reduced healthcare costs [27, 28]. A survey among Hungarian oncologists and haematologists showed that prescribers would increase rituximab use if a biosimilar were available, as 40% considered patient access to rituximab an issue [29].

Patients appear to heavily rely on the physician’s decision to use a biosimilar, as identified across multiple studies [16, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Among suggested solutions to improve patients’ biosimilar acceptance, communication and reassurance from HCPs, together with involvement in decision making, were mentioned [37]. A New Zealand survey identified the need among physicians for guidance on how to explain biosimilar treatment to patients [38].

Although earlier reports and the overall literature identified relatively low to moderate levels of knowledge and acceptability of biosimilars among stakeholders, improvements over time were identified. A survey conducted in 2013 among European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) members reported that the majority of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) specialists had little or no confidence about biosimilar use, expressing various concerns [10]. In 2015, ECCO repeated the survey, reporting fewer concerns and more confidence about biosimilar use among participants. IBD specialists were generally well informed and educated about biosimilars compared with the 2013 data [39]. Although improvements in stakeholder knowledge were mentioned in some studies, recent studies such as the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Association patient member survey published in 2019 signalled that awareness remains limited and stakeholders, in this case patients, continue to have concerns [40].

Recommendations on how to improve stakeholder acceptance mentioned in the literature included adapting clinical guidelines to reflect biosimilar use, implementing clear communication between physicians and patients, sharing real-world data with HCPs and educating prescribers about switch study data [41,42,43,44]. A few studies demonstrated that training stakeholders considerably improved their understanding and confidence in biosimilars [45, 46].

A structured overview of the original research studies about HCPs’ and patients’ biosimilar perspectives, including study parameters and main results, is given in the ESM 4.

3.2 Semi-Structured Interviews—Identifying Challenges and Actions to Improve HCP and Patient Understanding and Trust in Biosimilars

In total, 44 interviews were carried out. Participant characteristics are shown in ESM 5 and 6.

Overarching identified stakeholder challenges and proposed actions to improve stakeholder understanding and acceptance of biosimilars are shown in Fig. 2.

3.2.1 Improving Stakeholder Understanding About Regulatory Biosimilar Concepts

A lack of stakeholder knowledge and understanding of regulatory biosimilar concepts was identified as an important hurdle by most interviewees. Communication about the biosimilar regulatory approval pathway, reducing misconceptions about the biosimilarity concept, was deemed essential. Regulators emphasized that they have undertaken actions to improve stakeholder understanding about biosimilars, including the development and dissemination of informational materials in lay language for HCPs and patients, and the publication of biosimilar concept papers. Several interviewees mentioned that the robustness of the regulatory approval procedure should be emphasized in biosimilar stakeholder information.

3.2.1.1 Explaining the Rationale Behind Regulatory Biosimilar Evaluation to Address the Perceived Lack of Clinical Data

Across physician, pharmacist and regulator interviewees, it was generally recognized that the physicians’ understanding about the reduced role of clinical studies in biosimilar development and evaluation needs to be improved. “The gold standard of clinical trials does not hold true for biosimilars, where the focus is on analytical techniques that allow to obtain a high level of understanding about how the molecule works”. It was argued that this requires a mindset shift, as physicians are accustomed to the approval of new medicines, which undergo extensive clinical testing in phase I, II and III trials. Interviewees mentioned that many physicians are still arguing that there are too few clinical trials conducted for biosimilars, demonstrating that the concept of biosimilar development is not clear to all involved. “Doctors are trained to say: they don’t have the clinical trials, they didn’t do the effort”. Awareness and understanding about the development steps prior to the clinical part was deemed lacking: “Physicians need to learn that the clinical trial is the cherry on the cake, a confirmatory step of biosimilarity demonstrated in earlier development steps”.

Informing physicians about the framework through which biosimilars are evaluated was seen as key in increasing their and by extension also their patients’ trust in biosimilars. Regulators argued that stakeholders must be informed that “phase III trials are a rather blunt tool to detect potential differences, and more attention is paid towards the more sensitive PK/PD trial” and that the clinical programme is tailored towards the goal of the biosimilarity exercise, not a shortcut for developers, which may not be well understood by all. It should be explained that tailoring allows avoiding unnecessary delays, patient participation and development costs.

3.2.1.2 Extrapolation of Indications—Conveying Trust in the European Medicines Agency (EMA)’s Evaluation

It was mentioned that the concept of extrapolation of indications, albeit an imperative part of biosimilar development, is often misunderstood by stakeholders. Overall, it was stressed that extrapolation should be trusted as a scientifically valid part of a rigorous registration procedure. “Trust in the approval pathway also means applying the concept of extrapolation of indication.” One pharmacist mentioned that the decision regarding extrapolation is the regulator’s expertise field and should not be further questioned: “As a pharmacist, I rely at what the EMA decides. I trust that what is decided is based on decent evidence.” Although several nurses expressed some hesitations, the overall concept and application was accepted. “Someone else has decided that it is OK, so I don’t think any of us can say that more needs to be done”. Among patients, opinions varied about the application of extrapolation, ranging from trusting the EMA’s evaluation and mentioning that doing more than what scientifically would be needed should be avoided, to considering it as shortcut for developers.

Regulators indicated that it should be explained to stakeholders that extrapolation is not granted automatically and that exceptions can be applied if the studied indication would not be clinically representative or if questions about the mechanism of action across indications exist. A few pharmacists argued that regulators could “speak louder” about what extrapolation of indications entails. Interviewees generally believed that education on the biosimilar regulatory approval pathway is needed to further instil trust in extrapolation among stakeholders.

3.2.1.3 Interchangeability—A Need For One-Voice Guidance From Regulators

Table 1 provides definitions and considerations on interchangeability, switching and substitution in Europe.

Most pharmacists opined that a registered biosimilar could be considered interchangeable with its reference product. “If you establish this level of analytical similarity, together with a clinical study in a reference indication, with the same mechanism of action, then for me, there is no discussion about interchangeability.” Most physicians corroborated this opinion and believed that interchangeability between biosimilars and reference products is supported by the accumulated body of switch studies. Opinions of patients varied, ranging from a need for more data to agreeing with the physician’s decision. Regulators explained that additional clinical data, besides those requested in the registration procedure, are not needed from a scientific perspective, explaining why an interchangeability designation route imposing additional regulatory requirements as employed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [47] was not chosen in Europe. Although regulators explained that the mandate to regulate substitution lies outside the EMA’s remit and therefore the EMA does not provide guidance on interchangeability, approved biosimilars are considered interchangeable. It was mentioned that individual members of the Biosimilar Medicinal Products Working Party (BMWP) published a position paper about interchangeability [48], striving to provide guidance on a European level.

Some interviewees argued that the current divergent approach regarding interchangeability between the FDA and the EMA creates distrust among stakeholders. The FDA framework was believed to imply that some biosimilars are more similar to the reference product than others. Further, heterogeneity between the positions of National Competent Authorities (NCAs) regarding interchangeability was believed to lead to confusion.

Several physicians and pharmacists mentioned that it would be preferable for the EMA to address interchangeability by providing a clear position or by requesting switch studies as part of the registration procedure, similar to the FDA’s approach. A few physicians advocated that this would encourage developers to conduct one methodologically robust study, which would be preferred over the scattered landscape of smaller, real-world switch studies. One interviewee argued that this would settle the switch discussion before biosimilar market entry.

Regulators deemed interchangeability studies to require unnecessary time (delay in access) and financial investments, imposing additional challenges for biosimilar developers. Further, some regulators questioned how the FDA will address interchangeability over the product’s life cycle. Echoing the regulators’ viewpoint, some pharmacists deemed interchangeability studies a loss of time and resources, whereas others were in favour of extra data about sequential switching. Some interviewees believed that it is up to the physician to decide if they are comfortable with multiple exchanges. Some patients voiced concerns and argued that there is a lack of evidence to ensure the safety and efficacy of sequential switching.

Overall, interviewees deemed it important that robust records are maintained that allow adequate traceability in case any signals would emerge and that random switches are avoided. Regulators emphasized that existing pharmacovigilance systems should be able to capture any adverse drug reactions. It was mentioned that more attention needs to be paid to batch number recording.

3.2.1.4 Immunogenicity—Not a Biosimilar-Specific Concern

Many pharmacists and physicians emphasized that stakeholders should learn that immunogenicity is not a biosimilar-specific topic, as it could occur with any biological. “We need to explain what a biological is.” The immunogenicity topic is believed to have been fuelled by originator industry as an argument to instil fear and slow down biosimilar acceptance, as mentioned by several physician and pharmacist interviewees. “No one talked about immunogenicity issues before biosimilars arrived to the market”.

Further, some regulators and physicians argued that immunogenicity’s relevance depends on the molecule and that a risk-based assessment should be applied based on knowledge about the reference product. “I think that for the majority of biologicals immunogenicity is not so much a problem and definitely we shouldn’t make it one.”

Although immunogenicity assessment was believed to be addressed by the combination of a rigorous registration procedure and pharmacovigilance measures that allow longer-term monitoring, several interviewees suggested that improved traceability is needed to be able to attribute any possible immunogenicity signals to the involved product and batch. A few regulators mentioned that awareness of the importance of batch number reporting should be raised. Regulators also explained that stakeholders would benefit from knowing that immunogenicity is considered during biosimilar evaluation. A few interviewees anticipated that there could be an increase in immunogenicity reporting for biosimilars, as stakeholders tend to report more for ‘new’ products.

3.2.2 A Need for Education on Biological Medicines in General

In addition to continuing educating stakeholders about the scientific rationale behind the biosimilar regulatory approval process, several interviewees mentioned that educating stakeholders about biological medicines in general is necessary. Creating awareness among HCPs about the existence of manufacturing changes over the lifecycle of any biological and knowledge about their inherent variability was believed to provide perspective that the reference product is also not identical over time and to be pivotal in helping stakeholders understand the concepts behind biosimilarity. Increasing awareness about these aspects among clinicians could generate understanding about variability between products and provide insight into the evaluation of these differences.

3.2.3 The Request for Regulatory Guidance About Switching

Most HCP interviewees indicated that information about considerations for biosimilar use, such as guidance about switching, is needed. To address questions regarding switching, it was argued that governments needs to take up a more active role in informing, educating and providing guidance about biosimilars to HCPs and patients. To this end, several physicians and pharmacists voiced that NCAs need to formulate clear statements about biosimilar use. The existing NCA guidance was generally considered too cautiously formulated and “not fully in touch” with practical realities by several HCPs. Some regulators also mentioned that most NCAs only address reference product to biosimilar switching, arguing that guidance needs to be deepened and broadened. Several interviewees argued that guidance about switching on an overarching European regulatory level would be preferred, as it is now left open to the individual NCAs, leading to differences in recommendations, impacting stakeholder trust and confidence. A regulator counterargued that trust in biosimilar use essentially has to be created by stakeholder education. A few interviewees cautioned that overarching guidance should not translate into forced switching and that the decision making should remain with the physician.

3.2.4 Real-World Clinical Data Gathering to Instil Trust Among Stakeholders

Some physicians and nurses argued that real-world data could answer physicians’ demands for more clinical data, as it was argued to be reflective of clinical practice and often accompanied by expert opinion insights. Physicians and regulators indicated that switch study results can reassure physicians about switching. The NOR-switch trial [49] was raised as an example of such a post-approval initiative that increased physician confidence in biosimilars.

Clinical data gathering via registries was also considered to be helpful in increasing stakeholder confidence and reassuring stakeholders that the product performs well in every indication, instilling trust in extrapolation of indications. Further, registries were mentioned as gathering useful evidence about the long-term safety and efficacy of switching. In addition to clinical data, communication about real-life switch experiences was argued to be reassuring for stakeholders.

Several regulators cautioned that additional data-gathering expectations from HCPs could pose a barrier for biosimilar developers, as it requires sponsors to conduct expensive clinical studies beyond the licensing requirements and could also delay timely product uptake.

3.2.5 The Need for Practical and Stakeholder-Oriented Information

Interviewees across stakeholder groups emphasized the need for practical information about biosimilar products and biosimilar use.

Nurses believed that the information gap about biosimilars among fellow nurses is high. Nurses mentioned the need for specific biosimilar training to increase their knowledge to be able to correctly address potential patient questions. Most nurses also wanted to receive training about switch management: “What does it mean for the patient, why are we switching, what are the benefits?”

Several nurses also indicated the need for timely information about biosimilars entering the hospital. Organizing a product briefing session when a new product enters the hospital was suggested. Several interviewees mentioned that lessons should be derived from previous experiences, where switches were implemented without providing HCPs with necessary information. “One day we got the new medicine and we had to use it, change patients quickly without the right information, without a good answer why we needed to change”.

Several physicians also indicated that information should be tailored to the context in which the product is dispensed, that is, to the hospital or ambulatory setting and to the product category.

In addition to information about practical use, pharmacists asked for practical product-specific information, such as information about differences and similarities in approved indications, presentations, packaging and, if applicable, injection devices between the reference product and its biosimilar(s). Additionally, information about the expected biosimilar pipeline was considered necessary to allow for timely procurement planning. Guidance about the construction of award criteria was also believed to be useful to support their work. A nurse mentioned that the number of different products that are available for the same medicine, with potential differences in names, devices and indications, can confuse patients and HCPs, also expressing the need for a clear overview of product characteristics.

Patients argued that information should be provided in a simple, understandable and accessible way, tailored to basic health literacy levels. Providing written information with graphics or video material were suggestions to improve patient information. Several patients mentioned that information overshooting should be avoided, as not every patient is interested (“for many patients, it’s not an issue if it’s a biosimilar or a regular biological”) and it could instill concerns among patients (“why is there so much attention about this?”).

Several patients explained that patient information should be tailored to “inform about what the patient actually needs and wants to know”, that is, informing about the implications for the patient. Further, it was emphasized that patients wish to be informed about any adverse event risk.

Several HCPs mentioned specific initiatives that helped to generate practical biosimilar guidance, such as the Dutch Association of Hospital Pharmacists (NVZA) toolbox [50] that provides practical switch guidance and the European Specialist Nurses Organisations (ESNO) biosimilar booklet [51] providing communication and information guidance for nurses.

3.2.6 The Need For Impartial and Homogenous Information

Across interviews, the importance of impartial information regarding biosimilars, originating from independent bodies such as the EMA and NCAs, was stressed. Also, regulators believed that they are best suited to provide information about biosimilars, acting from a neutral position with knowledge from actual biosimilar assessments. The EMA/European Commission biosimilar stakeholder guidance documents [2, 52] were often mentioned during interviews as important and unbiased stakeholder information sources. One physician argued that awareness should be increased about the European Public Assessment Report, as it provides insights into regulatory evaluation and decision making.

Several interviewees across stakeholder groups considered that measures to actively counter misconceptions about biosimilars are necessary. Misconceptions were attributed by some to deceptive or commercially biased messaging by originator pharmaceutical industry protecting their market shares. “The issue is not so much the lack of information, but how the information is framed and presented”, “Companies have been successfully casting doubts about biosimilars”, “I don’t only need to educate, I have to dispel the angled information that has been presented. I’m already fighting against the tide, before I start.” Patients and nurses also indicated that misconceptions about biosimilars, including considerations about inferiority, should be tackled. Several regulators indicated that biosimilar regulatory concepts are misrepresented in an effort to set back stakeholder trust. Several interviewees advocated that existing sources should be interpreted with caution “to distinguish facts from nonsense”.

Convincing physicians who have been working with reference products for years appears to be challenging due to established relations with pharmaceutical companies, as mentioned by some interviewees. In contrast to most interviewees, several nurses identified pharmaceutical companies and their umbrella organizations as potential biosimilar educators.

Additionally, most regulators believed that “it’s not the lack of information, but the multitude and heterogeneity of information” that contributes to stakeholder misunderstanding about biosimilars. This argument was also made by several physicians, who mentioned that informational initiatives are scattered, leading to confusion, emphasizing the need for homogenous information.

3.2.7 Leading by Example—the Role of Key Opinion Leaders and Position Statements From Stakeholder Associations

Across all HCP stakeholder groups, interviewees mentioned that colleague key opinion leaders could play an important role in translating regulatory information into clear, concise statements, focused on practical considerations for biosimilar use. Generally, information from within their own stakeholder group (peer-to-peer information) was considered best suited and impactful to improve trust.

Several physician, regulator and patient interviewees advocated that key opinion leaders are likely to be considered as a trustworthy information source. “Prominent physicians who have experience are the best ones to deliver the experience to their colleagues”. Biosimilar ambassadors could actively guide biosimilar implementation and inform colleagues. The conception of dedicated biologics/biosimilar expert offices on a local level was proposed as an alternative route to help pave the way. Additionally, physicians considered that experience sharing by clinical disciplines that are already exposed to biosimilars could be leveraged to inform the next generation of stakeholders that will be confronted with biosimilars. Building from previous positive biosimilar experiences was argued to be an approach to increase trust by several interviewees. “It is a domino effect, when a few big hospitals are doing the switch, the others will follow.” “Once somebody else has done it, it takes some of the fear-factor away.”

Further, position statements by national and European scientific stakeholder associations were recognized as a lever to increase understanding among peers. It was remarked that continuous updating of position statements to reflect increasing experience and knowledge about biosimilars is needed. The increasing endorsement of regulatory concepts, such as extrapolation of indications, by medical stakeholder associations was mentioned as a positive evolution in this context.

3.2.8 The Importance of Multi-Stakeholder Aligned Efforts

Most interviewees across stakeholder groups advised that information and education should be a multi-stakeholder effort, ensuring that all stakeholders are able to communicate in the same way and can implement aligned decisions. Informing HCPs about biosimilars requires orchestrated action, initiated at regulatory approval, followed by information and guidance from the NCA and national scientific stakeholder associations upon national market entry. Specifically, regulators discussed that a more active collaboration between the EU and national regulatory authorities should be established, ensuring homogenous biosimilar information and targeted education streams. Further, a fostered collaboration between stakeholder groups was deemed necessary to translate regulatory information to stakeholder needs. Regulators and stakeholder organizations could write joint position papers, or information produced by the EMA could, after tailoring to the therapeutic area and stakeholder needs, be used at a local level. Governmental support was deemed desirable and NCAs were believed to be best suited to organize neutral education events locally. Several physicians emphasized that NCAs, together with medical/scientific societies, should take up a more active role.

It was argued that communication should also be an orchestrated multi-stakeholder effort at a hospital level. This multidisciplinary approach was deemed especially necessary in the context of switch management. Several interviewees argued that hospital pharmacists would be best suited to guide these multi-stakeholder initiatives for HCP colleagues (e.g. via Drug & Therapeutics Committees), acting as ‘biosimilar educators’ and guiding biosimilar use in hospitals. Specialized nurses could in turn support patients when switching.

3.2.9 Ensuring Active Uptake of Information

Several interviewees mentioned that approaches to ensure active uptake of the provided information should be explored, as the existing information is believed to penetrate the wider HCP and patient populations only slowly. Incorporating education on biosimilars in the stakeholder curricula was strongly supported across stakeholder groups. Suggestions were made to include biosimilar education as an obligatory part of the HCP accreditation system.

Gaining own practical experience with biosimilars in clinical practice (including switching) was also believed to establish trust among HCPs and patients by several interviewees. “It is not very scientific, but that is how it works for physicians”. Gaining experience with switching to a biosimilar was also argued to improve patient trust by some nurse interviewees: “Patients who tried the switch now accept it. They don’t think it is such a big thing anymore.”

4 Discussion

First, this study presented a structured review of the existing research on HCP and patient perceptions about biosimilars, identifying a clear need for continued evidence-based information and education initiatives to improve biosimilar understanding among HCPs and patients as knowledge about and acceptance of biosimilars is still variable and mostly unsatisfactory. Second, multi-stakeholder learnings and proposed solutions on how to improve stakeholder understanding and acceptance of biosimilars in Europe were gathered in semi-structured interviews with experts across stakeholder groups, reflecting the considerations of different stakeholders involved. In contrast to the studies identified in the literature review that mostly focussed on measuring stakeholders’ biosimilar knowledge, the qualitative part of this study identified expert insights on how to overcome stakeholder challenges to improve biosimilar understanding and adoption. This study also captured insights of nurses, whose perspective generally has been underreported so far.

As discussed during the interviews, increasing biosimilar understanding and acceptance among stakeholders requires a multifactorial and interdisciplinary approach. No silver bullet solution exists; rather, a coordination of efforts of different stakeholder levels is needed. Based on the synthesized study findings, we propose actions to be centred around ten actionable multi-stakeholder recommendations, which are presented in Table 2. These recommendations can inform policy making and other stakeholder initiatives to increase biosimilar understanding.

As recognized by the interviewees, extensive efforts have been made by European regulators to provide clear information regarding biosimilars and the science behind the regulatory evaluation to the public [2, 52,53,54,55,56,57]. Investments in providing unbiased biosimilar information and conveying trust in the regulatory evaluation must be continued (recommendation 1) to further improve stakeholder understanding. In particular, efforts to make this information more widely known to the target audience and to stimulate its active uptake are necessary (recommendation 10). To this end, biosimilar education should be included in both the curricula of future HCPs and in mandatory continuous learning programmes of practicing HCPs. Further, solution-oriented information programmes could be offered to HCPs to support them with biosimilar implementation at a local level. In the Netherlands, the Ministry of Health has subsidized such a biosimilar implementation programme that provides tailor-made support to hospitals [58, 59].

The basic training of HCPs should also focus on strengthening HCPs’ knowledge regarding biologics in general (recommendation 2), as some misconceptions regarding biosimilars may stem from a limited understanding about biologics. Further, HCP training should be enhanced by courses on drug development.

In addition to including biosimilar education in continuous learning programmes, sharing real-world clinical data about biosimilar use and switching may be effective to increase trust and acceptance among practicing HCPs (recommendation 4). Stakeholders indicated being reassured with regard to the safety of switching by the considerable number of switch studies that have been conducted over the last few years [60, 61]. Also, stakeholder experiences with biosimilar use should be actively disseminated via university or non-commercial-based educational outreach, key opinion leaders, and peer-to-peer communication to build trust (recommendation 5).

The EMA has no official position on interchangeability as prescribing practices and advice to prescribers fall under the responsibility of Member States [2]. Several Member States have released clear statements regarding interchangeability and switching [62]. An official, harmonized European regulatory position regarding interchangeability is believed to be needed, however, to provide clear and one-voice guidance to stakeholders across Member States. This will require a coordinated initiative and action between Member States and the EMA (recommendation 3).

On a practical level, stakeholders should be supported with product horizon scanning and structured product overviews to ensure timely and efficient biosimilar implementation (recommendation 6). Guidance materials, such as switch protocols, should be provided to support hospitals and HCPs at a local level (recommendation 7). Existing materials [50, 51, 58, 59, 63] could serve as examples and be tailored to the specific context.

The knowledge gap and misunderstanding among HCPs and patients has likely been amplified by the (in some cases intentional) dissemination of misinformation on biosimilars. Biosimilar misinformation exists in many forms, ranging from presenting factually incorrect information to negatively framing factually correct statements [64]. As shown in this study, industry involvement (from both originator and biosimilar manufacturers) in biosimilar stakeholder-related research is common (about one third of biosimilar stakeholder studies were either industry sponsored or conducted by industry). At times, originator industry involvement may have resulted in a more cautious or misleading representation of results to discourage biosimilar use. The originator industry’s reach may further trickle down via relations with or by actively involving opinion leaders and prescribers to amplify misconceptions and concerns, and as such creating uncertainty among their peers. In addition to providing accurate and unbiased information to stakeholders, biosimilar misinformation should be actively countered. Independent governmental bodies can act as designated entities to monitor and correct biosimilar misinformation, and address stakeholder queries in this regard (recommendation 8). Further, position statements from medical societies regarding biosimilar use should be regularly updated to reflect the evolving knowledge and experience with biosimilars. Continuing to foster the collaboration and dialogue between regulatory authorities and medical stakeholders can support this (recommendation 9) [65].

The second article of this series provides recommendations on how to improve biosimilar use in clinical practice and focusses on elements such as switching [8].

Whereas this study specifically aims to inform the European context, recommendations may be applicable on a wider scale, taking necessary tailoring to regional, cultural and policy specificities into account. Results from studies conducted in different regions of the world (Fig. 1) show that the main challenges with biosimilar stakeholder understanding are generally similar across jurisdictions. As most interviewed participants represent a Western European perspective, some findings may not be reflective of the needs of regions where, for example, accessibility is more challenging and therefore of greater concern. Shared expert insights mainly related to the experience with and considerations for anti-tumour necrosis factor products. Further, as most biological medicines are administered in or dispensed via the hospital, interview discussions predominately focussed on the hospital context and as such no public pharmacists were interviewed. Future research aimed at identifying specific learnings applicable to biosimilar use in ambulatory care would be useful as, in contrast with the hospital setting where decisions are generally driven by tenders and involve a drug formulary committee, here the decision to use biosimilars is generally based on individual prescriber perceptions. Tailoring of strategies to the treatment setting (hospital vs ambulatory care, chronic vs shorter term treatment), product type (more simple biologicals vs complex monoclonal antibodies) and patient’s needs is desirable.

Realising the structural, multi-stakeholder recommendations outlined in this study to improve biosimilar acceptance will require a proactive approach and a combination of governmental actions and policy measures on both a national and pan-European level.

5 Conclusion

Measures are needed to improve understanding and willingness to use biosimilars among stakeholders, in order to capture the biosimilar competition potential and its societal and patient benefits. The actionable recommendations proposed in this article can guide policy making and multi-stakeholder initiatives to improve stakeholder understanding about biosimilars. Providing stakeholders with objective information about the biosimilar approval pathway, ensuring active information uptake, dispelling biosimilar misinformation, providing product horizon scanning and communicating biosimilar implementation experiences are among the suggested actions.

References

European Medicines Agency. Guideline on similar biological medicinal products. 2014. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/similar-biological-medicinal-products.

European Medicines Agency and the European Commission. Biosimilars in the EU - Information guide for healthcare professionals. 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/leaflet/biosimilars-eu-information-guide-healthcare-professionals_en.pdf.

IQVIA. The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe. 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/31642/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

IQVIA. Advancing Biosimilar Sustainability in Europe—a Multi-Stakeholder Assessment. 2018https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/advancing-biosimilar-sustainability-in-europe.

European Medicines Agency. Biosimilar medicines. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/search_api_aggregation_ema_medicine_types/field_ema_med_biosimilar. Accessed 3 Jan 2020.

Dylst P, Vulto A, Simoens S. Barriers to the uptake of biosimilars and possible solutions: a Belgian case study. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32:681–91.

Moorkens E, Jonker-exler C, Huys I, Declerck PEMCJ_E, et al. Overcoming barriers to the market access of biosimilars in the European union: The case of biosimilar monoclonal antibodies. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:1–9.

Barbier L, Simoens S, Vulto AG, Huys I. European stakeholder learnings regarding biosimilars: part II—improving biosimilar use in clinical practice. BioDrugs. 2020;. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00440-z.

Lacey A, Luff D. Qualitative data analysis. The NIHR RDS for the East Midlands / Yorkshire & the Humber. 2007. https://web.rds-yh.shef.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/9_Qualitative_Data_Analysis_Revision_2009.pdf.

Danese S, Fiorino G, Michetti P. Viewpoint: Knowledge and viewpoints on biosimilar monoclonal antibodies among members of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2014;8:1548–50.

Attara G, Bressler B, Bailey R, Marshall J, Panaccione R, Aumais G. Canadian patient and caregiver perspectives on subsequent entry biologics/ biosimilars for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:S443–4.

Pasina L, Casadei G, Nobili A. A survey among hospital specialists and pharmacists about biosimilars. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;35:e31–3.

Sidikou O, Mondoloni P, Leroy B, Renzullo C, Coutet J, Penaud JF. Biosimilars: What do clinicians actually think? Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2016;23:A47–8.

Beck M, Michel B, Rybarczyk-Vigouret M-C, Leveque D, Sordet C, Sibilia J, et al. Knowledge, behaviors and practices of community and hospital pharmacists towards biosimilar medicines: Results of a French web-based survey. MAbs. 2017;9:384–91.

Cohen H, Beydoun D, Chien D, Lessor T, McCabe D, Muenzberg M, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv Ther. 2017;33:2160–72.

van Overbeeke E, De Beleyr B, de Hoon J, Westhovens R, Huys I. Perception of originator biologics and biosimilars: a survey among Belgian Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients and Rheumatologists. BioDrugs. 2017;31:447–59.

Schwartz Z, Schulz J, Vinther A, Kuklinski A, Saa K. Uncovering clinicians’ gaps and attitudes toward biosimilars: Impact of a 2-phase educational program. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Supplement 9):2814–5.

Giuliani R, Tabernero J, Cardoso F, McGregor KH, Vyas M, De Vries EGE. Knowledge and use of biosimilars in oncology: a survey by the European Society for Medical Oncology. ESMO Open. 2019;4:1–9.

Wong-Rieger D. Naive and expert patients’ knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about biosimilars. Value Healh. 2017;20:A17.

Aladul MI, Fitzpatrick RW, Chapman SR. Differences in UK healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude and practice towards infliximab and insulin glargine biosimilars. Int J Pharm Pract. 2019;27:214–7.

Robinson S, Mekkayil B, Hall T, Heslop P, Walker D. Patient experience of switching from Enbrel to Benapali. Rheumatology. 2019;58(Supplement):3.

Scherlinger M, Langlois E, Germain V, Schaeverbeke T. Acceptance rate and sociological factors involved in the switch from originator to biosimilar etanercept (SB4). Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:927–32.

Ighani A, Wang JY, Manolson MF. Biosimilar viewpoints from the perspective of psoriasis patients who use either biologic or systemic treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(Supplement 1):AB57.

Robinson K, Esgro R. Revealing and addressing knowledge gaps regarding biosimilars in rheumatology practice with targeted continuing education and patient surveys. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(Supplement 9):2808–9.

Karateev D, Belokoneva N. Evaluation of physicians’ knowledge and attitudes towards biosimilars in Russia and issues associated with their prescribing. Biomolecules. 2019;9:57.

Karki C, Baskett A, Baynton E, Lu Y, Shah-Manek B. Perceptions of cost pressure associated with biosimilars among physicians in Europe. Value Heal. 2018;21(Supplement 1):S253.

Baji P, Gulácsi L, Golovics PA, Lovász BD, Péntek M, Brodszky V, et al. Perceived risks contra benefits of using biosimilar drugs in ulcerative colitis: discrete choice experiment among gastroenterologists. Value Heal Reg Issues. 2016;10:85–90.

Azevedo A, Bettencourt A, Selores M, Torres T. Biosimilar agents for psoriasis treatment: the perspective of Portuguese patients. Acta Med Port. 2018;31:496–500.

Baer WH, Maini A, Jacobs I. Barriers to the access and use of rituximab in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a physician survey. Pharmaceuticals. 2014;7:530–44.

Berghea F, Popescu C, Ionescu R, Damjanov N, Singh G. Biosimilars use in rheumatology-the patient perspective. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1148.

Sekhon S, Rai R, McClory D, Whiskin C, Deamude M, Mech C, et al. Patient perspectives on the introduction of subsequent entry biologics in Canada. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:S663.

Badley E, Gignac M, Bowlby D, Gagnon K. Factors associated with decisions to transition to a different biologic, including biosimilar: The patients’ perspective. J Rheumatol. 2017;44:864.

Funahashi K, Yoshitama T, Tetsu Oyama T, Sagawa A, Katayama K, Matsubara T, et al. Survey on generic drugs (GE) and bio-similar drugs (BIO-S) of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and their doctors-cohort study of the Japanese clinician biologics research group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1471.

Kovitwanichkanont T, Wang D, Wapola N, Raghunath S, Kyi L, Pignataro S, et al. Biosimilar medicine is acceptable to patients if recommended by a rheumatologist in an Australian tertiary ra cohort. Intern Med J. 2018;48(Supplement 4):46.

Claudia C, Opris-Belinski D, Codreanu C. IR. Patient state of knowledge on biosimilars-do physicians need to improve education skills? Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(Supplement 2):1446–7.

Gary C, De Jodar SA, Deljehier T, Xuereb F, Bouabdallah K, Pigneux A, et al. Are patients and healthcare professionals willing to exchange the price of treatments to choose a biosimilar? experience based on the delphi method. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2019;26:A194.

Aladul MI, Fitzpatrick RW, Chapman SR. Patients’ understanding and attitudes towards infliximab and etanercept biosimilars: result of a UK Web-Based Survey. BioDrugs. 2017;31:439–46.

Hemmington A, Dalbeth N, Jarrett P, Fraser AG, Broom R, Browett P, et al. Medical specialists’ attitudes to prescribing biosimilars. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:570–7.

Danese S, Fiorino G, Michetti P. Changes in biosimilar knowledge among European Crohn’s Colitis Organization [ECCO] members: an updated survey. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2016;10:1362–5.

Peyrin-Biroulet L, Lönnfors S, Avedano L, Danese S. Changes in inflammatory bowel disease patients’ perspectives on biosimilars: a follow-up survey. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2019;7:1345–52.

Gavan S, Daker-White G, Barton A, Payne K. Exploring factors which influence anti-TNF treatment decisions for rheumatoid arthritis in England-a qualitative analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:131–2.

Jorgensen TS, Skougaard M, Asmussen HC, Lee A, Taylor PC, Gudbergsen H, et al. Communication strategies are highly important to avoid nocebo effect when performing non-medical switch from originator product to biosimilar product: Danish results from applying the Parker model a qualitative 3-step research model. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:2260.

Aladul MI, Fitzpatrick RW, Chapman SR. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions and perspectives on biosimilar medicines and the barriers and facilitators to their prescribing in UK: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:1–8.

Greene L, Singh RM, Carden MJ, Pardo CO, Lichtenstein GR, Care JM, et al. Strategies for overcoming barriers to adopting biosimilars. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25:904–12.

Murphy P, Amin V, Bill T, Candy I, Cheesman S, De Gavre T, et al. Impact of education programme on biosimilar attitudes and beliefs. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2017;23:59–60.

Willis L, Tanzola M. Biosimilars in oncology: An online activity has a significant educational impact on pharmacists. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019;25:19.

US Food & Drug Administration. Biosimilar and Interchangeable Products. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/biosimilars/biosimilar-and-interchangeable-products. Accessed 21 Aug 2020.

Kurki P, van Aerts L, Wolff-Holz E, Giezen T, Skibeli V, Weise M, et al. Interchangeability of biosimilars: a european perspective. BioDrugs. 2017;31:83–91.

Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, Lorentzen M, Bolstad N, Haavardsholm EA, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2304–16.

NVZA. NVZA Toolbox Biosimilars-Een praktische handleiding voor succesvolle implementatie van biosimilars in de medisch specialistische zorg. 2017. https://nvza.nl/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/NVZA-Toolbox-biosimilars_7-april-2017.pdf.

European Specialist Nurses Organisation. Switch management between similar biological medicines. https://www.esno.org/assets/files/biosimilar-nurses-guideline-final_EN-lo.pdf.

European Commission. Biosimilar medicines—information for patients. 2016. https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/26643.

Weise M, Bielsky M-C, De Smet K, Ehmann F, Ekman N, Giezen TJ, et al. Biosimilars: what clinicians should know. Blood. 2012;120:5111–7.

Weise M, Kurki P, Wolff-Holz E, Bielsky MC, Schneider CK. Biosimilars: the science of extrapolation. Blood. 2014;124:3191–6.

European Medicines Agency. Biosimilar medicines: overview. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview. Accessed 21 Aug 2020.

Wolff-Holz E, Garcia Burgos J, Giuliani R, Befrits G, De Munter J, Avedano L, et al. Preparing for the incoming wave of biosimilars in oncology. ESMO Open. 2018;3:e000420.

Gonzalez-Quevedo R, Wolff-Holz E, Carr M, Garcia BJ. Biosimilar medicines: why the science matters. Heal Policy Technol. 2020;9:129–33.

Instituut Verantwoord Medicijngebruik. Implementatie Biosimilars op Maat in ziekenhuizen (BOM). https://www.medicijngebruik.nl/projecten/informatiepagina/3749/totale-aanbod-gratis-materialen-en-scholingen-biosimilars-op-maat. Accessed 21 Aug 2020.

Biosimilars Nederland. Het Biosimilars-Nederland / IVM project: Biosimilars op Maat (BOM). https://www.biosimilars-nederland.nl/het-biosimilars-nederland-ivm-project-biosimilars-op-maat-bom/. Accessed 21 Aug 2020.

Barbier L, Ebbers H, Declerck P, Simoens S, Vulto A, Huys I. The efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of switching between reference biopharmaceuticals and biosimilars: a systematic review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108:734–55.

Cohen HP, Blauvelt A, Rifkin RM, Danese S, Gokhale SB, Woollett G, et al. Switching reference medicines to biosimilars: a systematic literature review of clinical outcomes. Drugs. 2018;78:463–78.

Medicines for Europe. Positioning Statements on Physician-led Switching for Biosimilar Medicines. 2019. https://www.medicinesforeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/M-Biosimilars-Overview-of-positions-on-physician-led-switching.pdf.

Cancer Vanguard Project Lead. CV pharma challenge: biosimilars ‘getting it right 1st time’. 2018. https://cancervanguard.nhs.uk/biosimilars-getting-it-right-first-time/.

Cohen HP, McCabe D. The Importance of Countering Biosimilar Disparagement and Misinformation. BioDrugs. 2020;34:407–14.

Annese V, Avendaño-Solá C, Breedveld F, Ekman N, Giezen TJ, Gomollón F, et al. Roundtable on biosimilars with European regulators and medical societies, Brussels, Belgium, 12 January 2016. GaBI J. 2016;5:74–83.

Barbier L, Mbuaki A, Simoens S, Vulto A, Huys I. PNS151 The role of regulatory guidance and information dissemination for biosimilar medicines—the perspective of healthcare professionals and industry. Value Heal. 2019;22:S786–7.

FDA. Biosimilar and Interchangeable Biologics: More Treatment Choices. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/biosimilar-and-interchangeable-biologics-more-treatment-choices. Accessed 6 Aug 2020.

Mehr S. Interchangeability, Switching, and What Happens Next. BR&R. 2020.https://biosimilarsrr.com/2020/07/24/interchangeability-switching-and-what-happens-next/. Accessed 6 Aug 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Funding

This manuscript is funded by the KU Leuven Fund on Market Analysis of Biologics and Biosimilars following Loss of Exclusivity (MABEL Fund).

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

IH, SS and AGV are founders of the KU Leuven Fund on Market Analysis of Biologics and Biosimilars following Loss of Exclusivity (MABEL Fund). AGV is involved in consulting, advisory work and speaking engagements for a number of companies, i.e., AbbVie, Accord, Amgen, Biogen, EGA, Pfizer/Hospira, Mundipharma, Roche, Novartis, Sandoz and Boehringer Ingelheim. SS was involved in a stakeholder roundtable on biologics and biosimilars sponsored by Amgen, Pfizer and MSD. He has participated in advisory board meetings for Pfizer and Amgen; and he has contributed to studies on biologics and biosimilars for Hospira, Celltrion, Mundipharma and Pfizer. IH and LB declare no conflict of interest. LB declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationship that could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Education-Guidance Committee for Medical Ethics in delegation of the Ethics Committee of UZ/KU Leuven (MP001375, Belgium).

Consent to participate

All interviewees provided their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

All interviewees provided their written informed consent for using the encoded and anonymized data from their interview for publication in scientific journals.

Availability of data and material

The interview data are not publicly available as they contain information that could compromise interviewees’ privacy and consent.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author’s contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. LB conducted the structured literature review. LB together with four pharmacy students conducted and coded the interviews. LB analysed the literature and interview data and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. No data, figures or tables have been published previously and the manuscript is not under consideration elsewhere.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the interviewees for their participation and willingness to share their insights. The authors also thank S. Ozcicek, S. Pinoy, L. Stragier and C. Vanneste for their help with conducting and processing interviews.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barbier, L., Simoens, S., Vulto, A.G. et al. European Stakeholder Learnings Regarding Biosimilars: Part I—Improving Biosimilar Understanding and Adoption. BioDrugs 34, 783–796 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00452-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00452-9