Abstract

The concept of a Health Promoting School has been found to be effective to improve health and well-being of students as well as a help with teaching and learning in school. Effective implementation of Health Promoting School is a complex intervention involving multi-factorial and innovative activity in many domains such as curriculum, school environment and community. Many studies evaluating Health Promoting School do not include outcomes reflecting the organisational or structural change as many of those studies are quantitative in nature and the statistical assumptions are not valid reflecting the organisational structure changes. Recent global meetings of experts have reviewed the impact on student health from the perspectives of school environment, school policies on health, action competencies on healthy living and community linkage. The English Wessex Healthy School Award Scheme and the Hong Kong Healthy School Awards Scheme have developed detailed systems to analyse whether each individual school has reached the standard of a model Health Promoting School reflecting a more holistic appreciation and understanding of all the effects of school-based health promotion with positive award-related changes. However, not many schools are able to implement Health Promoting School in its entirety, so cores indicators are needed as a starting point for wider implementation. Hong Kong Healthy School Awards Scheme is still ongoing with data for analysis of indicators with significant correlation with better health and well-being. We identified the core indicators and substantiated the requirements for successful outcomes by supplementing the established award-scheme framework with a review of recent literature and documents. Framework of Health Promoting School would go beyond improvement of health literacy to enable a more efficient system for education and health on children, hence a good investment in children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This paper highlights: |

How a healthy school award scheme would provide a comprehensive framework for development of Health Promoting Schools with core indicators as inputs for implementation. |

The details for implementation and the outcome measures for evaluation of Health Promoting School. |

1 Need for Updating on Health Promoting Schools

1.1 Health Promoting School Framework to Tackle Triple Health Burden

A recent paper on school health has raised the question of what constitutes school health with wide debate depending on geographic location, morbidity and mortality pattern of children and adolescents in the area, existing infrastructure and resources, and culture [1]. Equipping schools with the capacity to tackle the ‘Triple Health Burdens’: the emergence of ‘new’ communicable diseases, the epidemics of non-communicable disease (NCD) and the global burden of mental health, should be the fundamental vision and mission of a school. The ‘Triple Health Burdens” are challenges for both developed and developing countries of the contemporary world. The emergence of ‘new’ communicable diseases (the unexpected outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS] in 2003 with more than 1800 patients in over a dozen countries worldwide within two months, with clustering of cases in Hong Kong and Toronto [2]. The recent COVID-19 with over 1.1 millions confirmed cases globally (82,930 confirmed cases in China, over 600,000 cases in Europe and over 300,000 in America as on 5 April 2020) in over 100 countries within less than 3 months since outbreak in China at the time of writing [3]. This reminds us of the dictum of public health practice, ‘prevention better than cure’ [2, 3]. This is true not only for infectious disease but also for NCD. In 2011, the United Nations adopted ‘The Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of NCD’ [4]. The key action is to reduce risk factors and create health-promoting environments [5]. NCD accounts for one-third of premature deaths [6] so it is important to reduce the risk factors for NCD early. World Health Organization (WHO) published a ‘Mental Health Global Action Program’ and a ‘Movement for Global Mental Health’ in 2007 [7]. The disease burden for mental illness is estimated to show that the global burden of mental illness accounts for 32.4% of years lived with disability (YLDs) and 13.0% of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), instead of the earlier estimates suggesting 21.2% of YLDs and 7.1% of DALYs [8]. Effective school health intervention should target preventive measures at primary and secondary levels at an early stage. Health Promoting School (HPS) framework can help to build up effective preventive strategies in school setting.

Young people ought to be involved in school and community-based intervention for NCD [9]. Effective school health promotion programs in changing health behaviours are more likely to be complex, multi-factorial and innovative activity in many domains (curriculum, school environment and community) [10, 11]. During the eighties, WHO initiated the concept of HPS moving beyond individual behavioural change to consider organizational structure changes for health improvement covering six key areas: healthy school policies, school physical environment, school social environment, action competencies for healthy living, school health care and promotion services, and community link [12, 13]. Evidence should be gathered extensively about what schools actually do in health promotion using the HPS framework with a detail system of analysis how each individual school has reached the standard of a model HPS [13,14,15,16,17].

1.2 Healthy School Award Scheme to Establish High Quality Standard of HPS: Hong Kong Experience

The HPS model has shaped school health promotion in different parts of the world including the low-income countries [18]. The WHO Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!) guidance reiterates that “every school should be a health promoting school”, and recommends that “Countries that do not have an institutionalised national school health programme should consider establishing one and countries that do have such programme should continuously improve them to ensure that they align with the evidence base on effective interventions and emerging priorities” [19]. The English Wessex Healthy School Award Scheme (WHSA) [15] and the Hong Kong Healthy School Awards Scheme (HKHSA) by Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CHEP) [16, 17, 20] have developed detailed systems to analyse whether each individual school has reached the standard of a model HPS, reflecting a more holistic appreciation and understanding of all the effects of school based health promotion with positive award-related changes. The schools will undergo evaluation of the performance and status in relation to the six key areas of HPS adapted from the WHO’s guidelines to be considered for award. The evaluative process for HKHSA included reviewing the documentations, conducting interviews with teachers, parents and students as well as observation of school physical and social environment. Schools with HKHSA are recognised in the Healthy School Forum and on the CHEP’s website.

Data from the pre- and post-surveys of the 962 Primary 4 (P4) students and 1221 Secondary 3 (S3) students in five primary schools and four secondary schools presented to be audited for accreditation of HKHSA after 2 years of implementing the scheme were collected for analysis. Students from the schools which reached certain level of HPS standard as indicated by HKHSA, were compared with students whose schools did not receive the award, and the results showed significant improvement in self-reported health status and academic standings, certain health behaviours as well as satisfaction with life [21]. Primary 4 and Secondary 3 students were chosen to examine the changes for the cumulative impact of HPS at this mid-point of schooling. Another study adopted multi-stage random sampling among schools with awards and those schools not involved in the award scheme nor adopting the concept of HPS (non-HPS). For award group, 5 primary schools and 7 secondary schools were sampled for the study with 510 students and 789 students sampled respectively, and for the ‘Non-HPS’ group, there were 8 primary schools and 7 secondary schools sampled with 676 students and 725 students sampled respectively [22]. Students of the schools with award were found to be better with statistical significance in personal hygiene practice, knowledge on health and hygiene as well as access to health information [22]. Award schools were found to have better school health policy, higher degrees of community participation, and better hygienic environment [22]. CHEP was commissioned by Quality Education Fund of Hong Kong SAR Government to establish the Thematic Network of HPS aiming to sustain the HPS movement in 2010. The pattern of emotional health of students over years was analysed among 1204 primary 4 and 678 secondary 3 students of 17 primary schools and 5 secondary schools when they first joined the network in 2010. Similarly, to the rationale of previous study [21], students from those grades were chosen. The self-harm behaviours of students had dropped significantly among schools involved in the CHEP thematic network of HPS [23].

There are also numbers of papers analysing the data from the HKHSA as comprehensive system of monitoring and evaluation of performance of HPS [24,25,26,27,28]. Cochrane Review of WHO HPS framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement has been conducted [29]. The review was only based on 67 included cluster-randomised controlled trials (RCTs) taken place at the level of school, district or other geographical area. The RCT is not designed for testing organisational or structural change as the statistical assumptions underpinning RCT are not valid reflecting organisational or structural change because of the requirements of RCT such as blinding, randomisation, are needed for drawing statistical inference. Inchley et al. challenged whether HPS initiatives would lead to immediate change at the individual level, so one should study the potential markers of success associated with process [30]. Therefore, updating of HPS through scoping study is needed to identify the indicators of HPS to highlight the ways in which schools have adopted HPS principles successfully under the six key areas: healthy school policies, school physical environment, school social environment, action competencies for healthy living, school health care and promotion services, and community link [12, 13], and the conditions to be in place to flourish. There is also a need to review the evidence of HPS effectiveness on a boarder perspective dealing with complexity of the school system [31] to link education and health [18, 32]. The following sections report the findings from international forums, review of recent literature, documents and guidelines from international institutions on HPS and child and adolescent health to supplement and substantiate the core indicators and requirements evolved from HKHSA, an established award-scheme framework.

2 HPS and Better Health of Children and Adolescents: Reviewing Previous Studies/Research from International Consultation Meeting/Forum

Two global projects, (Global Consultation meeting on Emerging issues in Adolescent Health at Wingspread Conference Centre, USA [“Wingspread Consultation”]) in 2011 organised by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Stellenbosch Institute of Advanced Study on International Health Promoting School (HPS) Colloquium (“Stellenbosch Colloquium”) in South Africa in 2011 supported by Peter Wall Institute of Advanced Study of University of British Columbia, Canada); gathered leading scholars on child and adolescent health and HPS to shed further lights on HPS. They shared the recent science on different aspects of child and adolescent health to enlighten the direction of HPS development along the six key areas to improve health of children and adolescents more effectively.

The “Wingspread Consultation” explored the implications of recent research in the fields of epigenetics, adolescent neurodevelopment and neurobiology on adolescent health. Special journal issue reports the science challenging our thinking to place the individual adolescent within the context of both his/her environment, and within a life course perspective [33]. The linkage of policies and programmes to current understanding of science has added new insights on research on young people’s health [34]. Adolescent brain is associated with elevated activation of reward-relevant brain regions, and sensitivity to aversive stimuli may be attenuated [35]. Review of current biological models for addiction highlights the interactive influences of genetic and environmental contributions to addictive behaviours of adolescents supporting the evidence of preventive strategies targeting risk factors and enhancing protective factors at individual, familial and community levels [36]. Greater understanding of the epigenetic mechanism being dynamic in responding to both internal and external environmental stimuli has highlighted the new opportunities for development of early prediction and prevention paradigms with early intervention [33]. These new insights have led WHO to prioritise their interventions addressing the common social determinants of health risk behaviours of adolescents and the importance of the balance of action directed towards the policy and regulatory environment influencing individual behaviours [33].

“Stellenbosch Colloquium” was attended by 40 experts from 5 continents to share the global and regional experience surrounding HPS with Stellenbosch Consensus Statement [37]. There is agreement that both health promotion in school setting and HPS can have positive change in the lives of school children and the communities in which they live, and the capacity of HPS to:

-

reduce the burden of disease and improve the resilience of individuals and communities

-

be transformative for individuals, schools, and communities, enabling and empowering them to attain higher levels of function, and ultimately be stronger citizens with greater capacity for contribution to society

The other key areas of HPS, action competencies for healthy living and school health care and promotion services, need continuous enhancement to sustain those positive changes. Adopting the HPS model requires a change in mindset or a paradigm shift and refinement of educational investment and just provision of resources, engagement of non-government organisations (NGOs), or obtaining of international funding. The Consensus Statement has suggested some novel approaches including:

-

The opportunities that HPS create may provide common ground for alliance between government departments (particularly health and education), and between various disciplines, professionals and sectors. This “bridging” function may be one of the most powerful influences of successful HPS, and is likely to promote healthier public policy as well as more cost effective, equitable and higher quality collective action to promote wellness

-

Accreditation and rewards programmes that define commitment and recognise excellence may encourage schools to expand their health promoting programmes or to become HPS

-

Comprehensive evaluation methods are needed to adequately quantify the cost–benefit of health promoting programmes or HPS and their effectiveness.

There are not many accreditation and rewards programmes for recognising excellence in HPS. The WHSA [15] and HKHSA [16, 17, 20] have developed detailed systems to analyse whether each individual school has reached the standard of model HPS, reflecting a more holistic appreciation and understanding of all the effects of school-based health promotion with positive award-related changes. For HKHSA, based on the HPS Performance Indicators (PI) developed by CHEP, evaluation tool including sets of questions related to the PI were developed to assess the HPS status of the school. Stakeholders’ survey collected information from all teachers and non-teaching staff, 20% of all students and their parents. Additionally, the team would observe the school environment on the day of visit to evaluate the physical and social environment of the school. Individual interviews with the teachers and various posts of staff together with group interviews of parents and students were also conducted to retrieve information on the implementation of HPS and the health education and health promotion that had been conducted. WHSA scheme developed a set of indicators with a number of statements or targets relating to each area in which schools performed and the goals to achieve. Status of health education and promotion was assessed, and weaknesses and areas for development within the Award were identified as well as setting targets to be achieved. The tool was sent to schools for completion by a senior teacher and the co-ordinators of Physical Education (PE) and Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE) [14, 38].

WHSA was developed in the 1990s and HKHSA is still ongoing, and study has recently been conducted to identify core indicators with potential leading to better health and well-being [39]. Taiwan has taken reference from HKHSA to develop an award scheme for accreditation and awards [40]. “Wingspread Consultation” and “Stellenbosch Colloquium” have reinforced the importance of the six key areas of HPS being the main pillars for school health improvement. The existing established framework of HKHSA (Appendix 1) supplemented with review of recent literature and documents on HPS would identify the core requirements under the different key areas [school environment (physical and social), school policies on health, community links, action competencies, school health care and promotion services] to become an effective HPS.

3 Further Substantiation of Elements for Health Promoting School

3.1 Scoping Study

This update of HPS has taken reference from scoping reviews that are used to present a broad overview of the evidence related to the topic, irrespective of study quality, but useful to examine emerging areas to clarify concepts and identify gap [41, 42]. As explicit guidelines for scoping review are still emerging [41], this study makes use of scoping study which has included literature search and review of recent policies/guidelines/recommendations/reports/studies and other relevant documents on the current recommendation and implementation of HPS. The authors have already identified 20 indicators having significant impact on health-related outcomes [39], and the scoping study can provide detail standards of those core indicators under the five key areas (not including school health care and promotion services as explained later on) building on HKHSA framework based on WHO standard [11, 43] (Appendix 1). The sources of international documents come from leading global organisations such as WHO, UNESCO, World Bank, ASCD (Association of Superintendents and Curriculum Development) FRESH (Focusing Resource on Effective School Health) partnership and IUHPE (International Union for Health Promotion and Education) either as part of managerial practice or school health programme, were searched and reviewed as part of the scoping study. Literature search was also conducted from November to December 2018 using combination of literature search strategies to collect the research-based evidence, including electronic database queries (Global Health, Medline, PubMed), hand searching of key journals and consultation with experts and stakeholders with the following keywords: Healthy School or Healthy Schools or Health Promoting School or Health Promoting Schools. The grey literature was collected via Google and the leading academic/professional institutions on health promotion.

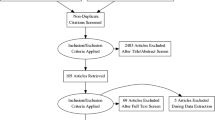

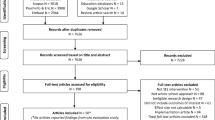

The documents included in the review are empirical studies describing health promotion action(s) in school (either managerial practice or school health programme) focused on student health, and based on a whole school approach, which committed to consider making change in HPS (either initiation or further development) and providing explicit information about the outcomes/impacts/opportunities/difficulties of the action(s) on a structural, organisational and/or individual level. A three-stage selection process has been conducted to screen out the included document for analysis. The selection process comprises:

-

review of the title and abstract by two researchers to determine the relevance for review. The document that does not fulfil the inclusion criteria (either not within the scope or insufficient information) will be excluded after reaching a consensus;

-

review of the full text of selected documents by two reviewers independently, based on a shared template to ensure internal validity and to further select the documents after discussion; and

-

analysis of the remaining documents by the researchers.

Details of the process are included in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) Flow Diagram (Fig. 1) [44]. As described earlier, literature search was conducted via electronic database queries (Global Health, Medline, PubMed) as well as hand searching of the key journals. A total of 1400 articles were retrieved using these methods. The research team underwent selection process of the papers and documents by their titles and abstracts. There were 183 full-text articles and documents being selected and assessed for eligibility by reviewing the abstracts. After reviewing the full text, reviewers excluded 71 papers that did not fit the criteria, and 112 papers were included. One researcher reviewed all the scientific papers, another reviewed all the selected international documents, and a third researcher reviewed the grey literature. During the review process, the researchers identified elements that would supplement the existing indicators of HKHSA. They categorised those elements and placed them under the related indicators as annotation to substantiate and/or expand the contents under each indicator. Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 provide substantive annotation of the different components and the respective elements of the five key areas of HPS. The key area, school health care and promotion services is not included, as this paper aims to focus more on educational investment particularly on bridging functions so school environment (physical and social), school polices on healthy school, community link and action competencies for healthy living are the key areas with greater significant impact. Children tend to learn their patterns of behaviours from the norms and values held by the school environment [45].

3.2 Findings

The scoping study provides detail standards of the core indicators (identified in another study [39]) under the five key area building on HKHSA framework based on WHO framework [11, 43].

With regard to Healthy School Policies, it is more applicable to define policy that would influence the behaviour of a manager or managed objects to influence and guide the school’s actions in promoting health and wellbeing of its students, staff, family and the wider community [46]. Table 1 shows how the position of health education and health promotion in school can be further substantiated [24, 31, 42, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58, 60,61,62,63,64, 84] and factors to be considered in reviewing existing policies related to health on four topics [50, 59, 65, 66] (healthy eating, safe school, harmonious school and student health care). School health profile should be created to reflect the needs responding to local priorities and the needs of all students, including marginalised children, and it should NOT be limited to narrowly defined health outcomes to be achieved through single health promotion. It should be articulation of the joint vision, mandate and framework for the HPS programme in a written policy to secure leadership and commitment, and should clarify resource allocation with strong and sustained integrated school health programming embedded within Education Sector Development Plan (Table 1). School should move towards “fostering coalescing leadership in combinations of leaders’ work together” to include students, and other educational personnel, parents and caregivers as well as outside service providers (Table 1). There should be re-orientation to new public health movement with emphasis on using structures and spaces to stimulate individual health-promoting behaviour, and schools need more-detailed guidelines related to physical structures, e.g. how to address hygienic standards and food safety (Table 1).

Safe and healthy conditions for the life and work of the whole school community can promote better teaching and learning, and also better interpersonal relationship. The school environment should be a place where students are free from danger, disease, physical harm or injury. Table 2 shows how school physical environment can be further enhanced under different elements to be more conducive for health and safety [13, 50, 67,68,69,70]. The eating environment should emphasise health in terms of nutrition and hygiene including food safety (Table 2). Children learn their patterns of behaviours either prosocial or antisocial from the norms and values held by the social environment in which they are bonded [45]. The school environment should be a place where all students are free from fear or exploitation, and codes against misconduct exist and are enforced with clear rules and procedures for responding to aggressive acts and ensuring that students, staff and parents are aware of and enforce these rules and procedures (Table 3). Different elements under different components of school social environment can be further substantiated to create the values conducive for desirable social behaviours (Table 3) [49, 50, 53,54,55, 59, 71,72,73,74,75,76]. Students should be engaged and empowered in planning and implementing school activities. School needs to cultivate socially supportive relationships giving people a sense of being valued and cared for with reciprocity. This can be promoted through a teaching curriculum and extra curricula activities that place the importance of opportunities for pupils (Table 3).

Information can improve people’s knowledge about the health consequences of their choices, but there is little evidence that information alone changes behaviour. Enhancement of action competencies on healthy living is needed with a comprehensive health education curriculum to enhance personal health skills and developed strategically with professional development of teachers. Table 4 shows how those perspectives can be further enhanced under different elements [26, 49, 50, 52,53,54, 56, 57, 59, 68, 69, 76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83]. For example, schools should ensure student participation in programme implementation to enhance their capacity and connectedness to the programme, using diverse learning and teaching strategies to account for different learning styles including and making use of real-life conditions as “life skills education” so students can gain insights into matters related to health (Table 4). The ethos of HPS should be part of the curriculum in teacher training and education to strengthen teachers’ understanding of student’s participation in class with paradigm shift of delegating school health promotion activities to lay school health counsellors not only relying education or health professionals together with improved system of monitoring and evaluation of health education needs in school setting (Table 4).

Community can synergise and synchronise with school initiatives and intended learning outcomes rather than adopting passive roles and even expressing hesitation. Community members can appreciate a balanced approach recognising the importance of academic and non-academic factors and values of developing social and human capitals to nurture young people. Schools would also develop deeper understanding of the needs of the community to enable schools acting as agents of change in the lives of students, families and communities. Table 5 shows how different elements under different components of community link can substantiate the effect of linkage with community [49,50,51, 53, 54, 57, 73, 84, 85, 86]. Strong linkage with community can ensure a consistent approach across the school and between the school, home and wider community, and the knowledge exchanged would enable the community-based partner to provide a better service to the school and the school benefits from receiving higher quality products (Table 5).

4 Proposed Key Standards for HPS and Outcome Measures

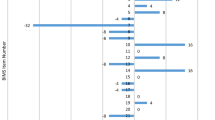

Tables 12, 3, 4 and 5 provide detail standards of the core indicators under the five key area building on HKHSA framework (Online Appendix 1). Study by Lee et al. has identified those indicators to have significant impact on health-related outcomes [39] and those core indicators can be good starting point for wider implementation of HPS because not many schools are able to implement in full scale [24, 87]. Table 6 lists 19 core indicators from 5 key areas reflecting the inputs of HPS performance. The outcome measurements of the different indicators can take reference from the Hong Kong Student Health Survey Questionnaire (HKSHQ) [23, 40] measuring the student health-related outcomes. HKSHQ incorporates the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth Risk Behavioural Surveillance [88] and WHSA [15] adapted by CHEP [20, 21] with continuous refinement as a tool for assessing student health status/health-related outcomes [23, 89]. K6 scale by Kessler and colleagues [90] has been used to assess emotional disturbance as well as the Life Satisfaction scale by Huebner and colleagues [91] as part of HKSHQ building up the student health profile. Table 6 provides the core indicators as inputs for HPS performance and also the possible outcome measurements. This should serve as a basic framework for HPS standard with outcome measures to evaluate the HPS effectiveness. Apart from providing a framework for holistic approach to improve health literacy [92], HPS can also provide a framework for holistic approach to improve school’s organisation and culture.

No detailed scoping study was conducted on the key area, school health care and promotion services and one would take reference from the “Forum for Investing in Young Children Globally” (iYCG) initiated by the Institute of Medicine (now renamed as National Academy of Medicine), USA during the period 2014–2016 [93]. Keynote by Dr Helia Molina, past Minister of Health in Chile described an integrated system in Chile based on an intersectoral public policy on childhood and social protection in one iYCG workshop in 2015 with the theme ‘Using existing platforms to integrate and co-ordinate investments for children’ [94].

5 Conclusion

The scoping study has enriched the contents of the core indicators under the five key areas. There are now more updated details of standards required under each core indicator taking reference from global experience in implementation of HPS (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). The findings of this paper can provide explicit information on ways to implement HPS under the different key elements (the core indicators) of different key areas, namely school environment (physical and social), school polices on healthy school, community link and action competencies for healthy living. This would enable and empower the school setting to integrate and co-ordinate a more efficient education, health and social system for healthy child development. HPS is good framework for inter-sectoral approach, and the findings of this paper would provide practical guidance for practitioners to learn how to make a start.

References

Lee A. School health programs in the Pacific Region. In: McQueen D, editor. Oxford Bibliographies in Public Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199756797-0173.

Lee A, Cheng FF, Yuen H, Ho M. How would schools step up public health measures to control spread of SARS? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(12):945–9.

WHO. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report - 76. Geneva: WHO. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200405-sitrep-76-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=6ecf0977_4. Accessed 6 Apr 2020.

United Nations General Assembly. Political declaration of the high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. New York: United Nations; 2011.

Mant D. Principle of Prevention. In: Jones R, Britten N, Culpeper L, et al., editors. Oxford textbook of primary medical care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004.

Norheim OF, Jha P, Admasu K, Godal T, Hum RJ, Kruk ME, Gómez-Dantés O, Mathers CD, Pan H, Sepúlveda J, Suraweera W. Avoiding 40% of the premature deaths in each country, 2010–30: review of national mortality trends to help quantify the UN Sustainable Development Goal for health. Lancet. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61591-9.

Patel V, Collins PY, Copeland J, Kakuma R, Katontoka S, Lamichhane J, Naik S, Skeen S. The movement for global mental health. Br J Psychiatry. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074518.

Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2.

Jourdan D, Christensen JH, Darlington E, Bonde AH, Bloch P, Jensen BB, Bentsen P. The involvement of young people in school-and community-based noncommunicable disease prevention interventions: a scoping review of designs and outcomes. BMC Public Health. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3779-1.

Nutbeam D, Clarkson J, Phillips K, Everett V, Hill A, Catford J. The health-promoting school: organisation and policy development in Welsh secondary schools. Health Educ J. 1987;46(3):109–15.

Peters LWH, Kok G, Ten Dam GT, Buijs GJ, Paulussen TG. Effective elements of school health promotion across behavioral domains: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-182.

WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Health-promoting schools series 5: regional guidelines. Development of health-promoting schools—a framework for action. WHO/WPRO; 1996.

Marshall BJ, Sheehan MM, Northfield JR, Maher S, Carlisle R, Leger LH. School-based health promotion across Australia. J Sch Health. 2000;70(6):251–2.

St Leger L, Nutbeam D. Research into health promoting schools. J School Health. 2000;70(6):257–9.

Moon AM, Mullee MA, Rogers L, Thompson RL, Speller V, Roderick P. Helping schools to become health-promoting environments—an evaluation of the Wessex Healthy Schools Award. Health Promot Int. 1999;14(2):111–22.

Lee A, Cheng F, Yuen H, Ho M, Lo A, Fung Y, Leung T. Achieving good standards in health promoting schools: preliminary analysis one year after the implementation of the Hong Kong Healthy Schools Award scheme. Public Health. 2007;121(10):752–60.

Lee A, St Leger L, Cheng F, Hong Kong Healthy School Team. The status of health-promoting schools in Hong Kong and implications for further development. Health Promot Int. 2007;22(4):316–26.

Heesch KC, Hepple E, Dingle K, Freeman N. Establishing and implementing a health promoting school in rural Cambodia. Health Promot Int. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day114.

World Health Organization. Introduction to Global Accelerated Action for the Health of Adolescents (AA-HA!): Guidance to Support Country Implementation. 2017. https://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/framework-accelerated-action/background/en/. Accessed 1 June 2019.

Lee A. Helping schools to promote healthy educational environments as new initiatives for school based management: the Hong Kong Healthy Schools Award Scheme. Promot Educ. 2002;9(1_suppl):29–32 (Renamed as Global Health Promotion).

Lee A, Cheng FF, Fung Y, St Leger L. Can Health Promoting Schools contribute to the better health and wellbeing of young people? The Hong Kong experience. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(6):530–6.

Lee A, Wong MCS, Keung VMW, Yuen HSK, Cheng F, Mok JSY. Can the concept of Health Promoting Schools help to improve students’ health knowledge and practices to combat the challenge of communicable diseases: case study in Hong Kong? BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):42.

Lee A, Keung V, Lo A, Kwong A. Healthy School environment to tackle youth mental health crisis. Hong Kong J Paediatr. 2016;21(2):134–5.

Joyce A, Dabrowski A, Aston R, Carey G. Evaluating for impact: what type of data can assist a health promoting school approach? Health Promot Int. 2017;32(2):403–10.

Moynihan S, Jourdan D, Mannix McNamara P. An examination of health promoting schools in Ireland. Health Educ. 2016;116(1):16–33.

Macnab AJ, Gagnon FA, Stewart D. Health promoting schools: consensus, strategies, and potential. Health Educ. 2014;114(3):170–85.

Macnab AJ, Stewart D, Gagnon FA. Health promoting schools: initiatives in Africa. Health Educ. 2014;114(4):246–59.

St Leger L, Young IM. Creating the document ‘Promoting health in schools: from evidence to action’. Glob Health Promot. 2009;16(4):69–71.

Langford R, Bonell CP, Jones HE, Pouliou T, Murphy SM, Waters E, Komro KA, Gibbs LF, Magnus D, Campbell R. The WHO Health Promoting School framework for improving the health and well-being of students and their academic achievement. Cochrane Database systematic Rev. 2014;4:CD008958.

Inchley J, Muldoon J, Currie C. Becoming a health promoting school: evaluating the process of effective implementation in Scotland. Health Promot Int. 2006;22(1):65–71.

Rowling L. Strengthening, “school” in school mental health promotion. Health Educ. 2009;109(4):357–68.

Turunen H, Sormunen M, Jourdan D, Von Seelen J, Buijs G. Health promoting schools—a complex approach and a major means to health improvement. Health Promot Int. 2017;32(2):177–84.

Bustreo F, Chestnov O. Emerging issues in adolescent health and the positions and priorities of the world health organization. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:S4.

Blum R, Dick B. Strengthening global programs and policies for youth based on the emerging science. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2):S1–3.

Spear LP. Adolescent neurodevelopment. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(2):S7–13.

Potenza MN. Biological contributions to addictions in adolescents and adults: prevention, treatment, and policy implication. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:S22–32.

Macnab A. The Stellenbosch consensus statement on health promoting schools. Glob Health Promot. 2013;20(1):78–81.

Moon AM, Mullee MA, Rogers L, Thompson RL, Speller V, Roderick Moon AM, Mullee MA, Thompson RL, Speller V, Roderick P. Health-related research and evaluation in schools. Health Educ. 1999;99(1):27–34.

Lee A, Lo ASC, Keung MW, Kwong CM, Wong KK. Effective Health Promoting School for better health of children and adolescents: indicators for success. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1088. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7425-6.

Chen FL, Lee A. Health-promoting educational settings in Taiwan: development and evaluation of the Health-Promoting School Accreditation System. Glob Health Promot. 2016;23(1_suppl):18-25.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Kastner M, Levac D, Ng C, Sharpe JP, Wilson K, Kenny M. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16(1):15.

McIsaac JLD, Mumtaz Z, Veugelers PJ, Kirk SF. Providing context to the implementation of health promoting schools: a case study. Eval Progr Plan. 2015;53:65–71.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Catalano RF, Oesterle S, Fleming CB, Hawkins JD. The importance of bonding to school for healthy development: findings from the Social Development Research Group. J Sch Health. 2004;74(7):252–61.

Wies R. Policy definition and classification: aspects, criteria and examples. In: Proceedings of the IFIP/IEEE international workshop on distributed systems: operation and management; 1994. pp. 10–12.

Simovska V. What do health-promoting schools promote? Processes and outcomes in school health promotion. Health Educ. 2012;112(2):84–8.

Babazadeh T, Fathi B, Shaghaghi A, Allahverdipour H. Lessons learnt from pilot field test of a comprehensive advocacy program to support health promoting schools’ project in Iran. Health Promot Perspect. 2017;7(1):14.

Shahhosseini Z, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Female adolescents’ perspective about reproductive health education needs: a mixed methods study with explanatory sequential design. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;27(1):57–63.

FRESH M&E Coordinating Group. Monitoring and Evaluation Guidance for School Health Programs. FRESH M&E Coordinating Group. 2014. https://hivhealthclearinghouse.unesco.org/sites/default/files/resources/FRESH_M&E_CORE_INDICATORS.pdf. Accessed 30 Aug 2019.

Lee A, Cheung MB. School as setting to create a healthy learning environment for teaching and learning using the model of health promoting school to foster school-health partnership. J Profess Capac Community. 2017;2(4):200–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-05-2017-0013.

World Health Organization. Health Promoting School: experiences from the Western Pacific Region. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2017. http://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/13551/9789290617884-eng.pdf. Accessed 30 Aug 2019.

International Union for Health Promotion and Education (IUHPE). Achieving Health Promoting Schools: Guidelines for promoting health in schools. IUHPE. 2009. https://www.iuhpe.org/images/PUBLICATIONS/THEMATIC/SCHOOL/FacilitatingDialogueHE_EN.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

IUHPE. Promoting health in school: From evidence to action. IUHPE. 2010. https://www.iuhpe.org/images/PUBLICATIONS/THEMATIC/HPS/Evidence-Action_ENG.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

ASCD. Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child (WSCC). A collaborative approach to learning and health. ASCD. 2014. http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/siteASCD/publications/wholechild/wscc-a-collaborative-approach.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

IUHPE. Facilitating Dialogue between the Health and Education Sectors to advance School Health Promotion and Education. IUHPE. 2012. https://www.iuhpe.org/images/PUBLICATIONS/THEMATIC/HPS/Evidence-Action_ENG.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

Safarjan E, Buijis G, de Ruiter S. School action planner: A companion document for the SHE online school manual. SHE. 2013. http://www.schoolsforhealth.eu/for-schools/. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

Global Partnership for Education and World Bank Group. School Health Integrated Programming (SHIP) Extension: final report. Global Partnership for Education and World Bank Group. 2018. https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/school-health-integrated-programming-ship-extension. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

Barnekow V, Buijs G, Clift S, Jensen BB, Paulus P, Rivett, D, Young I. Health-promoting schools: a resource for developing indicators. International Planning Committee, European Network of Health Promoting Schools; 2006.

Kam CM, Greenberg MT, Walls CT. Examining the role of implementation quality in school-based prevention using the PATHS curriculum. Prev Sci. 2003;4(1):55–63.

Stewart-Brown S. What is the evidence on school health promotion in improving health or preventing disease and, specifically, what is the effectiveness of the Health Promoting Schools approach? Geneva: World Health Organization. 2006. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/74653/E88185.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

Weare K, Markham W. What do we know about promoting mental health through schools?. Promot Educ. 2005;12(3–4):118–22 (renamed as Global Health Promotion).

West P. School effects research provide new and stronger evidence in support of the health-promoting school idea. Health Educ. 2006;106(6):421–4.

Hoyle TB, Samek BB, Valois RF. Building capacity for the continuous improvement of health-promoting schools. J Sch Health. 2008;78(1):1–8.

Lee A, Lo A. Keung V, Kwong A. Healthy school policies. Theory and practice of health promoting school: getting started. Hong Kong: Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2018.

Saewyc DM. School health services: fulfilling the promise for prevention: background document for a global expert consultation. Geneva: WHO Maternal Neonatal Child and Adolescent Health Branch; 2017.

Bellomo AJ. Emergency management. In: Frumkin H, Geller RJ, Rubin IL, Nodvin J, editors. Safe and healthy school environments. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. p. 270–94.

Phaitrakoon J, Powwattana A, Lagampan S, Klaewkla J. The diamond level health promoting schools (DLHPS) program for reduced child obesity in Thailand: lessons learned from interviews and focus groups. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2014;23(2):293–300.

UNESCO. UNESCO Strategy on Education for Health and Well-being: Contributing to the sustainable development goals. UNESCO. 2016. https://hivhealthclearinghouse.unesco.org/sites/default/files/resources/FRESH_M&E_CORE_INDICATORS.pdf. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

Cohen DA, Scribner RA, Farley TA. A structural model of health behavior: a pragmatic approach to explain and influence health behaviors at the population level. Prev Med. 2000;30(2):146–54.

Gordon J, Turner K. School staff as exemplars–where is the potential? Health Educ. 2001;101(6):283–91.

Ministry of Education, Denmark. The Folkeskole (Consolidation) Act, Consolidation Act No. 730 of 21 July 2000 as amended by section 64 of Act No. 145 of 25 March 2002, section 2 of Act No. 274 of 8 May 2002, section 1 of Act No. 412 of 6 June 2002, section 54 of Act No. 1050 of 17 December 2002, section 8 of Act No. 297 of 30 April 2003, section 1 of Act No. 299 of 30 April 2003 and by Act No. 300 of 30 April 2003. Copenhagen: Ministry of Education. 2003. http://eng.uvm.dk/publications/laws/folkeskole.htm?menuid=2010.

Brown KM, Elliott SJ, Robertson-Wilson J, Vine MM, Leatherdale ST. Can knowledge exchange support the implementation of a health-promoting schools approach? Perceived outcomes of knowledge exchange in the COMPASS study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):351.

Resnick MD, Harris LJ, Blum RW. The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well-being. J Paediatr Child Health. 1993;29:S3–9.

Blum RW, McNeely CA, Rinehart PM. Improving the odds: the untapped power of schools to improve the health of teens. U.S.A: Center for Adolescent Health and Development, University of Minnesota; 2002.

Duckett P, Kagan C, Sixsmith J. Consultation and participation with children in healthy schools: choice, conflict and context. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;46(1–2):167–78.

Nyberg G, Sundblom E, Norman Å, Elinder LS. A healthy school start-Parental support to promote healthy dietary habits and physical activity in children: design and evaluation of a cluster-randomised intervention. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):185.

St Leger LH. The opportunities and effectiveness of the health promoting primary school in improving child health—a review of the claims and evidence. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(1):51–69.

Simovska V. Student participation: a democratic education perspective—experience from the health-promoting schools in Macedonia. Health Educ Res. 2004;19(2):198–207.

World Health Organization. European framework for quality standards in school health services and competencies for school health professionals. World Health Organization. 2014. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/246981/European-framework-for-quality-standards-in-school-health-services-and-competences-for-school-health-professionals.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

Speller V, Byrne J, Dewhirst S, Almond P, Mohebati L, Norman M, Polack S, Memon A, Grace M, Margetts B, Roderick P. Developing trainee school teachers’ expertise as health promoters. Health Educ. 2010;110(6):490–507.

Gugglberger L. Support for health promoting schools: a typology of supporting strategies in Austrian provinces. Health Promot Int. 2011;26(4):447–56.

Rajaraman D, Travasso S, Chatterjee A, Bhat B, Andrew G, Parab S, Patel V. The acceptability, feasibility and impact of a lay health counsellor delivered health promoting schools programme in India: a case study evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):127.

Khatib IM, Hijazi SS. Adaptation of the school health index to assess the healthy school environment in Jordan. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17(1):62–8.

Nkamba EM, Tilford S, Williams SA. Components of Health Promoting Schools in Ugandan primary schools: a pilot study. Int J Health Promot Educ. 2008;46(3):84–93.

Himmelman AT. Collaboration for a change. Definitions, models, roles and a guide for collaborative process. Minneapolis: Hubert Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota. 2002.

Adamowitsch M, Gugglberger L, Dür W. Implementation practices in school health promotion: findings from an Austrian multiple-case study. Health Promot Int. 2017;32(2):218–30.

Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI, Ross JG, Lowry R, Grunbaum JA, Kolbe LJ. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 1999. J Sch Health. 2000;70(7):271–85.

Lee A, Keung VM, Lo AS, Kwong AC, Armstrong ES. Framework for evaluating efficacy in health promoting schools. Health Educ. 2014;114(3):225–42.

Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Bromet E, Cuitan M, Furukawa TA, Gureje O, Hinkov H, Hu CY, Lara C. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(S1):4–22.

Huebner ES, Seligson JL, Valois RF, Suldo SM. A review of the brief multidimensional students’ life satisfaction scale. Soc Indic Res. 2006;79(3):477–84.

Lee A. Health Promoting Schools: evidence for a holistic approach in promoting health and improvement of health literacy. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2009;7(1):11–7.

National Academy of Medicine. CONCEPT NOTE: Forum on Investing in Young Children Globally. An activity of the Board on Children, Youth, and Families and Board on Global Health at Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of The National Academy of Sciences. Washington, DC. The National Academy of Medicine, 2017. http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Activity%20Files/Children/iYCG/iYCG%20Concept%20Paper.pdf. Accessed 2 Sep 2019.

Molina H. Integrated and Co-ordinated Programme in Chile. iYCG Workshop. Institute of Medicine, Centre for Health Education and Health Promotion and Wu Yee Sun College of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. March 14-15, 2015, Hong Kong. In National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (2015). Using existing platforms to integrate and co-ordinate investments for children: Summary of a joint workshop. Chapter 3: A collaborative Multiplier Approach To Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC. The National Academic Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.17226/23637.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere thanks to Ceci HY Chan for her assistance in literature search at the early stage of the project. The authors would like to thank Quality Education Fund of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Government to support the Hong Kong Healthy School Award Scheme and Thematic Network of Health Promoting School.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lee is responsible for overall design of the review, reviewing literature to be included, and analysing literature to identify elements substantiating the indicators for HPS, and responsible to summarise all findings in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 and developed the key standards of HPS and outcome measures. Lo is responsible for searching documents and grey literature to be included and analysing documents, grey literature and literature. Li is responsible to search for literature, documents and grey literature, and organization of findings from the analysis. Keung and Kwong are responsible for checking of findings.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding has been received for preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors want to express sincere thanks to Quality Education Fund of Hong Kong SAR Government for supporting the Hong Kong Healthy School Award and Thematic Network of Health Promoting School. There is no conflict of interests in preparing this manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, A., Lo, A., Li, Q. et al. Health Promoting Schools: An Update. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 18, 605–623 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-020-00575-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-020-00575-8