Abstract

Background

There has been a proliferation of repeat prenatal ultrasound examinations per pregnancy in many developed countries over the past 20 years, yet few studies have examined the main determinants of the utilization of prenatal ultrasonography.

Objective

The objective of this study was to examine the influence of the type of provider, place of residence and a wide range of socioeconomic and demographic factors on the frequency of prenatal ultrasounds in Canada, while controlling for maternal risk profiles.

Methods

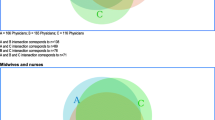

The study utilized the data set of the Maternity Experience Survey (MES) conducted by Statistics Canada in 2006. Using an appropriate count data regression model, the study assessed the influence of a wide range of socioeconomic, demographic, maternal risk factors and types of provider on the number of prenatal ultrasounds. The regression model was further extended by interacting providers with provinces to assess the differential influence of types of provider on the number of ultrasounds both across and within provinces.

Results

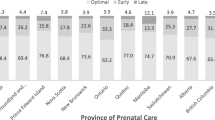

The results suggested that, in addition to maternal risk factors, the number of ultrasounds was also influenced by the type of healthcare provider and geographic regions. Obstetricians/gynaecologists were likely to recommend more ultrasounds than family physicians, midwives and nurse practitioners. Similarly, birthing women who received their care in Ontario were likely to have more ultrasounds than women who received their prenatal care in other provinces/territories. Additional analysis involving interactions between providers and provinces suggested that the inter-provincial variations were particularly more pronounced for family physicians/general practitioners than for obstetricians/gynaecologists. Similarly, the results for intra-provincial variations suggested that compared with obstetricians/gynaecologists, family physicians/GPs ordered fewer ultrasound examinations in Prince Edward Island, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Alberta and Newfoundland.

Conclusion

After controlling for a number of socioeconomic and demographic factors, as well as maternal risk factors, it was found that the type of provider and the province of prenatal care were statistically significant determinants of the frequency of use of ultrasounds. Additional analysis involving interactions between providers and provinces indicated wide intra- and inter-provincial variations in the use of prenatal ultrasounds. New policy measures are needed at the provincial and federal government levels to achieve more appropriate use of prenatal ultrasonography.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In 2005–2006, Canadian hospitals reported an estimated $2.2 billion for the operation of diagnostic imaging services; this was up from the $2.0 billion reported in 2004–2005 [18].

It should be noted here that the numbers of ultrasounds included in the data were those resulting from provider referrals and, as such, they were publicly funded. The data excluded non-referral ultrasounds performed at private diagnostic imaging centres at the request of birthing women. The latter were not publicly funded.

We applied the Poisson finite-mixture model to our data, using two-component Poisson finite-mixture models. The first class (the low-utilization rate group) accounted for 95 % of the sample population, and the second class (the high-utilization group) accounted for only 5 %. Moreover, comparison of the mean and variance of the two components indicated that the first component had a mean of around 2.9, which was close to the overall sample mean. Since the distinction between the two components becomes more blurred or fragile in such cases, we decided not to use this model [30].

In order to compare the performance of various count data models, we used the log-likelihood and AIC and BIC criterion. The model with larger values of log-likelihood and smaller values of AIC and BIC are preferred [30]. The results are available from the authors upon request.

The moments of the numbers of ultrasounds indicates that the distribution was moderately skewed right, with the skewness and kurtosis being 0.65 and 2.60, respectively.

Guidelines in Canada recommend one complete ultrasound in the second trimester (18–20 weeks’ gestation) in a normal pregnancy as a part of routine pregnancy care [33]. Although each province in Canada follows the national clinical guidelines, the administration and delivery of health care services is the responsibility of each province/territory, guided by the provisions of the Canada Health Act [34].

There were a few respondents who were reported to be immigrant and aboriginal. Since the focus was on Canadian Aboriginals, these cases were recorded as immigrants.

Testing for the equality of coefficients on the second and third trimesters indicated that they could be aggregated.

Initially, we created separate dummies for each type of provider. However, testing for the equality of coefficients on provider type indicated that certain types of provider could be aggregated.

Other types of provider (nurses, midwives and others) were not interacted with provinces, because of the small numbers of observations of these providers in some provinces.

The reimbursement rates for different types of provider vary across provinces/territories in Canada. The National Physician Database published by the Canadian Institute of Health information suggests that family physicians, on average, are paid $40.51 per service for total consultation and visits, and that obstetricians/gynaecologists are paid $49.72 per service. However, there are quite a lot of variations across provinces. For family physicians, the costs per service for consultations and visits range from $28.90 in Newfound and Labrador to $54.06 in Alberta, whereas for obstetricians/gynaecologists, they vary from $37.16 in Newfoundland and Labrador to $80.45 in British Colombia [49].

References

Ewigman B, Crane J, Frigoletto F, et al. Effect of prenatal ultrasound screening on perinatal outcome. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:821–7.

Kongnyuy E, Broek N. The use of ultrasonography in obstetrics in developing countries. Trop Doct. 2007;37(2):70–2.

Saari-Kemppainen A, Karjalainen O, Ylostalo P, et al. Ultrasound screening and perinatal mortality: controlled trial of systematic one-stage screening in pregnancy (Helsinki trial). Lancet. 1990;336:387–91.

Thompson E, Freake D, Worrall G. Are rural general practitioner–obstetricians performing too many prenatal ultrasound examinations? Evidence from western Labrador. CMAJ. 1998;158:307–13.

You J, Alter D, Stukel T, et al. Proliferation of prenatal ultrasonography. CMAJ. 2010;182(2):143–51.

Garcia J, Bicker L, Henderson J, et al. Women’s views of pregnancy ultrasound: a systematic review. Birth. 2002;29:225–50.

Marinac-Dabic D, Krulewitch C, Moore R. The safety of prenatal ultrasound exposure in human studies. Radiology. 2002;13(3 Suppl):19S–22S.

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). What mothers say: the Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey (2009). http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/rhs-ssg/survey-eng.php. Accessed 6 Jul 2013.

Youngblood J. Should ultrasound be used routinely during pregnancy? An affirmative view. J Fam Pract. 1989;29:657–60.

Wellesley D, Vigan C, Baena N, et al. Contribution of ultrasonographic examination to the prenatal detection of trisomy 21: experience from 19 European registers. Ann Genet. 2004;47(4):373–80.

Jorgensen F. An epidemiological study of obstetric ultrasound examinations in Denmark 1989–1990. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1992;71(7):513–9.

Yates J, Lumley J, Bell R. The prevalence and timing of obstetric ultrasound in Victoria 1991–1992: a population-based study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;35(4):375–9.

You J, Alter D, Iron K, et al. Diagnostic services in Ontario: descriptive analysis and jurisdiction review (2007). http://www.ices.on.ca/file/Diagnostic_Services_Ontario_Oct16.pdf. Accessed 6 Jul 2013.

Iglehart J. The new era of medical imaging—progress and pitfalls. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2822–8.

Newnham J, Evans S, Michael C, et al. Effects of frequent ultrasound during pregnancy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1993;342:887–91.

Bucher H, Schmidt J. Does routine ultrasound improve outcome in pregnancy? Meta-analysis of various outcome measures. BMJ. 1993;307:13–7.

Bricker L, Garcia J, Henderson J, et al. Ultrasound screening in pregnancy: a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and women’s views. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4(16):i-vi, 1-193.

Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Medical imaging in Canada, 2007 (2008). http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/products/MIT_2007_e.pdf. Accessed 6 Jul 2013.

Filly R, Crane J. Routine obstetric sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:713–8.

Raynor B. Routine ultrasound in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;46:882–9.

Bethune M. Time to reconsider our approach to echogenic intracardiac focus and choroid plexus cysts. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48(2):137–41. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00826.x.

Canada Health. Canadian perinatal health report, 2003. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2003.

Bly S, Van den Hof M. Obstetric ultrasound biological effects and safety. SOGC Clinical Practice Guideline 160. Diagnostic Imaging Committee, Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. JOGC. 2005;27(6):572–5.

Campbell J, Elford R, Brant R. Case–control study of prenatal ultrasonography exposure in children with delayed speech. CMAJ. 1993;149:1435–40.

Salvesen K, Vatten L, Eik-Nes S, et al. Routine ultrasonography in utero and subsequent handedness and neurological development. BMJ. 1993;307:159–64.

Anderson G. Use of prenatal ultrasound examination in Ontario and British Colombia in the 1980s. JSOGC. 1994;16:1329–38.

Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, et al. Regional variations in diagnostic practices. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):45–53.

Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti D, Larson E. Rising use of diagnostic medical imaging in a large integrated health system. Health Aff. 2008;27(6):1491–502.

Cameron A, Trivedi P. Regression analysis of count data. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998.

Cameron A, Trivedi P. Microeconometrics using stata: revised edition. College Station: STATA Press; 2010.

Rao J, Wu C. Resampling inference with complex survey data. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83(401):231–41.

Rao J, Wu C, Yue K. Some recent work on resampling methods for complex surveys. Surv Methodol. 1992;18:209–17.

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC). Guidelines for ultrasound as a part of routine prenatal care. J SOGC. 1999;78:1–6.

Health Canada. Health care system: provincial/territorial role in health (2009). http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/delivery-prestation/ptrole/index-eng.php. Accessed 6 Jul 2013.

Cleary-Goldman J, Malone F, Vidaver J, et al. Impact of maternal age on obstetric outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5):983–90.

Newburn-Cook C, Onyskiw JE. Is older maternal age a risk factor for preterm birth and fetal growth restriction? A systematic review. Health Care Women Int. 2005;26(9):852–75.

Stafford R, Misra B. Variations in routine electrocardiogram use in academic primary care practice. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2351–5.

Sirovich B, Gallagher P, Wennberg D, et al. Discretionary decision making by primary care physicians and cost of US health care. Health Aff. 2008;27:813–23.

Roos N, Roos L. High and low surgical rates: risk factors for area residents. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(6):591–600.

Wennberg J, Gittelsohn A. Variations in medical care among small areas. Sci Am. 1982;1982(246):120–34.

Chan B, Austin P. Patient, physician, and community factors affecting referrals to specialists in Ontario, Canada: a population-based, multi-level modelling approach. Med Care. 2003;41(4):500–11.

Zuckerman S, Waidmann T, Berenson R, et al. Clarifying sources of geographic differences in Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):54–62.

Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Giving birth in Canada: providers of maternity and infant care. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2004.

British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health (BCCEWH). Solving the maternity care crisis: making way for midwifery’s contribution. Policy series. Vancouver: British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health; 2003.

Ikegami N, Campbell J. Health care reform in Japan: the virtues of muddling through. Health Aff. 1999;18:26–36.

Fraser W, Hatem-Asmar M, Krauss I, et al. Comparison of midwifery care to medical care in hospitals in the Quebec pilot projects study: clinical indicators. Can J Public Health. 2000;91(1):5–11.

Rosenblatt R, Dobie S, Gary Hart L. Interspecialty differences in obstetric care of low-risk women. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(3):344–51.

Siddique J, Diane S, Tyler J, et al. Trends in prenatal ultrasound use in the United States 1995 to 2006. Med Care. 2009;47(11):1129–35.

Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI). National physician database, 2010–11 data release. http://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?pf=PFC2032&lang=en&media=0. Accessed 6 Jul 2013.

Gudex C, Nielsen B, Madsen M. Why women want prenatal ultrasound in normal pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:145–50.

Meire H. Ultrasound-related litigation in obstetrics and gynecology: the need for defensive scanning. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;7:233–5.

Studdert D, Mello M, Sage W, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialist physicians in a volatile malpractice environment. JAMA. 2005;293(21):2660–2.

Baldwin L, Hart L, Lloyd M, et al. Defensive medicine and obstetrics. JAMA. 1995;274:1606–10.

Goyert G, Bottoms S, Treadwell M, et al. The physician factor in cesarean birth rates. New Eng J Med. 1989;320:706–9.

Rock S. Malpractice premiums and primary cesarean section rates in New York and Illinois. Public Health Rep. 1988;103:459–63.

Dobie S, Hart G, Fordyce M, et al. Do women choose their obstetric providers based on risks at entry into prenatal care? A study of women in Washington State. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84(4):557–64.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author duly acknowledges funding from the Manitoba Research and Data Center for preparation of this article. The authors have no conflict of interest that are directly relevant to the content of the article. The authors would like to thank anonymous reviewers and editor for their invaluable comments and suggestions on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Harminder Guliani contributed to the study design, statistical analysis and preparation of the manuscript; Ardeshir Sepehri contributed to the study design, statistical analysis and review of the results; John Serieux assisted with review and interpretation of the results. All authors made critical revisions of the final manuscript. The corresponding author takes responsibility for the overall content.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Guliani, H., Sepehri, A. & Serieux, J. Does the Type of Provider and the Place of Residence Matter in the Utilization of Prenatal Ultrasonography? Evidence from Canada. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 11, 471–484 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-013-0046-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-013-0046-9