Abstract

Introduction

Controversy exists regarding the indication of beta-blockers (BB) in different scenarios in patients with cardiovascular disease. We sought to evaluate the effect of BB on survival and heart failure (HF) hospitalizations in a sample of pacemaker-dependent patients after AV node ablation to control ventricular rate for atrial tachyarrhythmias.

Methods

A retrospective study including consecutive patients that underwent AV node ablation was conducted in a single center between 2011 and 2019. The study's primary endpoints were the incidence of all-cause mortality, first HF hospitalization and the cumulative incidence of subsequent hospitalizations for HF. Competing risk analyses were employed.

Results

A total of 111 patients with a mean age of 73.9 years were included in the study. After a median follow-up of 45.5 months, 43 patients had died (38.7%) and 31 had been hospitalized for HF (27.9%). The recurrent HF hospitalization rate was 74/1000 patients/year. Patients treated with BB had a non-significant trend to higher mortality rates and a higher risk of recurrent HF hospitalizations (incidence rate ratio 2.23, 95% confidence interval 1.12–4.44; p = 0.023).

Conclusion

After an AV node ablation, the use of BB is associated with an increased risk of HF hospitalizations in a cohort of elderly patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In patients with pacemaker and AV node ablation, beta-blockers use is associated with increased risk of heart failure hospitalization. |

Chronotropic effects appear to be largely responsible for the benefits of beta-blockers in patients with heart failure. |

1 Introduction

Beta-blockers (BB) have been demonstrated to improve survival after myocardial infarction and in patients with heart failure (HF) and reduced ejection fraction, and are commonly used for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) for heart rate control [1,2,3]. But the benefits of these drugs are restricted to a limited number of patients, i.e., BB have proven symptom relief and survival improvement in patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), but these benefits do not seem to translate to patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [4]. In the setting of AF, BB are the first-line therapy for rate control, but surprisingly, in patients with coexisting AF and HFrEF, two pathologies where BB are indicated, their benefits have been questioned [5].

BB exert a complex effect on the cardiovascular system, which includes chronotropic, inotropic, lusotropic and bathmotropic effects on the heart, as well as vasodilation and/or vasoconstriction at the vascular level. In clinical practice, dose titration is mainly driven by two factors, hypotensive effects and principally bradycardic effects, the target being for most patients a resting heart rate between 60 and 70 beats per minute.

Pacemaker dependency is defined as the absence of an adequate intrinsic rhythm. It includes several cardiac conditions like high-degree or complete AV block with sinus rhythm or AF, and some cases of sinus node disease or bradycardic AF [6]. Some of these conditions may have occasional intrinsic rhythm and even tachycardic episodes, and most patients with AV block and sinus rhythm have dual-chamber pacemakers that preserve the patient’s intrinsic rhythm. In order to select a population of patients in whom the heart rate is completely dependent on the pacemaker, we decided to study patients with an AV node ablation and programming of the pacemaker in VVI or VVIR mode, most of them with permanent AF. This population does not respond to chronotropic effects, limiting the effect of BB to vascular effects, and at the cardiac level to inotropic effects, and to a lesser extent bathmotropic and lusotropic effects. In some centers, it is common practice to withdraw BB after AV node ablation. However, this is not universal practice, and overlooks the possible beneficial effects independent of heart rate control.

We sought to evaluate the effect of BB on survival and HF events in a sample of pacemaker-dependent patients after AV node ablation to control ventricular rate for atrial tachyarrhythmias.

2 Methods

This was a retrospective study including all consecutive patients that underwent AV node ablation in a single center between 2011 and 2019. The study’s primary endpoints were the incidence of all-cause mortality, first HF hospitalization and the cumulative incidence of subsequent hospitalizations for HF. The diagnosis of HF was codified if patients had at least one hospitalization with such main diagnosis on a discharge medical report and those with typical signs and symptoms of HF that had a compatible imaging diagnosis (echocardiogram) or pro brain natriuretic peptide (proBNP) result [2]. Patients with reduced, mildly reduced and preserved ejection fraction were included in the study. Risk factors, clinical antecedents, treatments and complementary tests were registered from all patients by trained medical staff after the AV node ablation.

Patient follow-up was performed under a well-established protocol via outpatient clinics, phone calls, review of electronic medical reports and institutional databases. The vital status was assured by phone calls in the absence of medical reports.

The local institutional ethics committee approved the study, which conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.1 Statistical Analyses

The distribution of continuous variables was analyzed using the Kolmogorov Smirnov test and the stem-and-leaf plot. Normally distributed variables were presented as mean (standard deviation [SD]), and differences were assessed by t Student and Chi-square tests. Variables with a non-normal distribution were expressed as median (interquartile range) and compared by Mann Whitney U test if they were not normally distributed. Qualitative variables are presented as percentages, and differences were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. Survival analyses were performed after verifying the proportional risk assumption by the Schoenfeld residuals test.

The risk estimates for post-discharge HF could be affected by patients’ survival status. Therefore, the usual techniques for time-to-event analysis would provide biased or un-interpretable results due to competing risks, and the Kaplan-Meier estimation will overestimate the HF incidence. To avoid such effects, we applied the model introduced by Fine and Gray [7] to test the competing events. The incidence of HF is presented in cumulative incidence function graphs and results of the multivariate analysis as sub-hazard ratio (sHR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Harrell’s C-statistic test was used to assess the model’s discrimination. Calibration was tested by the Gronnesby and Borgan test. Patients lost during follow-up were categorized as missing, as well as those who lacked any of the main variables for the analyses, although these were < 5%.

Recurrent hospitalizations were evaluated by determining the incidence rate ratio (IRR) by a negative binomial regression. Because an increase in HF hospitalizations is associated with an increased risk of subsequent death, it has been suggested that any analysis of recurrent admissions should also account for death as a terminal event. Thus, coefficients from this method were estimated by accounting for the positive correlation between the recurrent outcome and death as a terminal event by linking the two simultaneous equations (rehospitalization count and death) with shared frailty [8]. Thus, within the same model, we obtained estimates of risk for both endpoints. Covariate selection was performed based on previous medical knowledge. The covariates included in the final predictive model for both endpoints were age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, previous coronary artery disease, HF, stroke, revascularization, left ventricle ejection fraction, glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin, and medical treatments at discharge. Harrell’s C-statistics and calibration of the model were 0.701 (95% CI 0.600–0.791) and 0.873, respectively.

A two-tailed p value of < 0.05 was statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA 15.1. (StataCorp, 2017, Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX).

3 Results

3.1 Study Population

The final study sample consisted of 111 patients. The mean age was 73.9 ± 9.6 years, and 50 patients (45%) were women. A total of 74 (66.7%) were on BB, and the other 37 patients (33.3%) were not on BB treatment.

At the time of AVN ablation, 95.5% of the patients had current or previous AF, 37.8% typical or atypical atrial flutter and eight (7.2%) had other supraventricular tachycardia. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 44.8 ± 16.14%. Eighty patients (72.1%) had previous HF. Previous HF hospitalization was more frequent among patients with reduced ejection fraction (97.3%) than in those with mildly reduced (85.7%) or preserved ejection fraction (70.7%).

Fifty patients had a single-chamber pacemaker (45.0%), 21 a dual-chamber pacemaker (18.9%) and 36 a cardiac resynchronization device (32.4%). In all cases, the programming was set in VVI or VVIR modes. Eighty-five had a pacemaker (76.6%) and 26 an implantable defibrillator device (23.4%).

3.2 Differences Between Patients on and off Beta-Blockers (BB)

Table 1 describes baseline characteristics of the study population stratified by BB therapy. Patients on BB had a higher proportion of previous coronary artery disease (36.5% vs 10.8%, p = 0.003), HF (83.8% vs 48.6%, p < 0.001), cancer (18.9% vs 5.4%, p = 0.040) and lower mean left ventricular ejection fraction (42.36% vs 51.9, p = 0.018). The medical treatment did not differ significantly, except for a higher proportion of statins (56.8% vs 29.7%, p = 0.007) and diuretics (68.9% vs 45.9%, p = 0.019).

There were no significant differences according to the type of device: 27.0% of Implantable cardioverter defibrillators among patients on BB versus 16.2% patients off BB (p = 0.205) and 39.2% resynchronization versus 16.2% patients off BB (p = 0.066).

3.3 Events

Follow-up was available for all patients, and after a median follow-up of 45.5 months (interquartile range 19.4–70.1), 43 patients had died (38.7%) and 31 (27.9%) had had an HF episode requiring hospital admission—14 patients just one HF hospitalization and the remaining 17 had recurrent hospitalizations. The number of HF hospitalizations ranged from 0 to 12, and the number of days hospitalized ranged from 0 to 99.

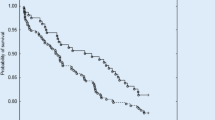

Patients treated with BB had a non-significant trend to higher mortality rates (Fig. 1). Cumulative incidence of first HF hospitalization was statistically higher in patients treated with BB (Fig. 2). Recurrent HF hospitalization rate was 74/1000 patients/year, and it was almost 2.5-fold higher in patients treated with BB (Fig. 3). The multivariate analysis, adjusted by age, sex, creatinine, left ventricle ejection fraction, coronary artery disease and previous HF, revealed a higher risk of recurrent HF hospitalizations in patients treated with BB (IRR 2.23, 95% CI 1.12–4.44; p = 0.023) (Table 2).

4 Discussion

In this retrospective observational study, we selected a sample of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices and AV node ablation, in whom heart rate was independent of the intrinsic rhythm and of the mediation. In this population, BB use was associated with a significant increase of HF hospitalizations. This is the first study evaluating the effects of BB in such a population, and thus discriminating the chronotropic effects from the rest of the cardiovascular effects of the BB.

4.1 BB and Heart Failure (HF)

The effects of BB in HF vary depending on the type of patient. In patients in sinus rhythm and with left ventricular dysfunction, there is solid evidence of the benefits of their use, whereas in patients with AF or in those with preserved ventricular function, their benefits are more questionable. The Beta-blockers in Heart Failure Collaborative Group, in a meta-analysis with individual patient data, showed that while BB use was associated with a 27% relative reduction in all-cause mortality in patients with sinus rhythm, patients with AF did not show any benefit from being treated with BB. These results were similar when cardiovascular mortality or readmissions for HF were evaluated [5]. In our study, most patients had AF, and as opposed to patients in sinus rhythm, those in AF have no better prognosis when heart rate is lower [9].

Interestingly, in patients with paroxysmal AF, pulmonary vein isolation ablation seems to restore BB benefits in patients with HF [10].

In the setting of HFpEF, the benefits of BB are even less clear. Although most studies show benefits of BB for patients with mildly reduced ejection fraction, most report lack of benefits for patients with ejection fraction above 50% [4]. Despite this lack of solid evidence, most patients with HFpEF are currently being treated with BB [11, 12]. There is not a unique explanation for this fact, but we speculate that the main reasons are the lack of a pharmacological treatment for these patients and the efficacy of BB for prevention and treatment of the main triggers of HF: hypertension, AF, and coronary artery disease.

Hospital admissions for HF are a major health problem. They affect both patients with HF and with AF, and are associated with a marked reduction in survival and quality of life and an increase in healthcare costs [13,14,15].

4.2 BB in Pacemaker Patients

Pacemaker dependence is defined as the absence of an adequate intrinsic heart rhythm. It is a complex phenomenon that includes a variety of heart rhythm diseases: patients with sinus bradycardia or sinus arrest, bradycardic AF, complete or high degree AV block.

Patients may take up to 10 years to develop pacemaker dependency [16], but it is variable among patients and studies, and in most patients, we should expect to find progressive disease of the conduction system. Pacemaker dependence has also been estimated in cohorts of patients with defibrillators, and it is estimated that between 10 and 20% of patients receiving an implantable defibrillator will become pacemaker dependent in the follow-up [17, 18].

Although most patients are dependent or not, there are some with intermittent pacemaker dependency [6, 16]. In some cases, the heart rate is driven by the pacemaker, but in others, it is mainly driven by the patient’s intrinsic rhythm.

Pacemaker dependency has been associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [19], highlighting the importance of appropriate pharmacological therapy.

BB have proven to reduce intraventricular dyssynchrony in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy and normal QRS [20], but theoretically it could increase the percentage of ventricular pacing in patients with conventional pacemakers and thus produce paced-induced cardiomyopathy [21].

Previous studies that have evaluated heart rhythm in HF patients have excluded those with pacemakers, and when they have considered them, they have done so as if they were a homogeneous group. Patients with cardiac pacing devices have different percentages of pacing dependence, and many patients with bi- or tri-chamber devices may have sinus rhythm that is perfectly sensitive to the effects of the BB and use the pacemaker to assure the transmission of AV conduction. In this study, all patients had any type of atrial tachycardia and AV node ablation, nullifying the chronotropic effects of the drugs.

4.3 Biological Effects of BB

BB have proven benefits in terms of ventricular function, ventricular remodeling, HF symptoms, morbidity and mortality [4, 22]. However, the mechanisms behind these effects are not fully understood. Possible explanations are the reduction of heart rate, reduction of cardiac afterload, the alleviation of neurohormonal effects, the reduction of intraventricular dyssynchrony, improvement of coronary flow reserve, antiapoptotic effects or the ability to counteract metabolic disturbances caused by adrenergic hyperactivation [20, 23,24,25]. Although we mainly use heart rate as the reference for BB indication, titration and follow-up, it is only one of the multiple effects these drugs have on the circulatory system.

Some studies have demonstrated an increase in the central blood pressure associated with the BB use, which increases cardiac afterload, and an additional increase in the ventricular load caused by the augmentation of the ventricular volume and pressure secondary to the increased filling interval caused by the bradycardic effects [26, 27].

The effect of BB on circulating brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal-pro brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) levels is again complex, as BB have proven to markedly reduce natriuretic peptide levels in HFrEF [28], while it increases them in patients with HFpEF [29].

In addition, and probably with more effect in this specific population, bradycardia is not associated with a better prognosis in AF patients, as it is in patients in sinus rhythm [9, 30], and it has been speculated that BB treatment may favor the appearance of significant pauses and pause-dependent ventricular tachycardias [31].

With the analysis of the published evidence and our own results, we hypothesize that patients with HF and AF with a pacemaker-dependent heart rate do not benefit from BB therapy for the following reasons: First, the chronotropic action of the drugs has no effect in these patients. Second, the hypotensive effect of BB may not be well tolerated in patients with HF and may limit the use of other drugs with proven benefit, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers or neprilysin inhibitors. Third, although BB have shown benefit in patients with AF and also in patients with HF, interestingly, this benefit seems to disappear when both conditions are combined, as is the case of our patients, and the addition of the AV node ablation makes the use of bradycardia drugs even more futile. Last, in polymedicated patients, any drug that does not provide significant benefit may exert a negative effect in terms of drug interactions, side effects and reduced therapeutic adherence to other drugs with proven benefits.

4.4 Strengths and Limitations

This study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First is the inherent limitations of retrospective studies, which are prone to selection bias and confounders that may not be sufficiently adjusted with the multivariate analysis. The selection of symptomatic patients who have required AV node ablation may have excluded those patients medical treatment with BB has managed to stabilize. In addition, some relevant variables such as body mass index were not available for inclusion in the multivariate analysis. Second, another limitation is the lack of continuous evaluation of BB therapy, type of BB and doses, as well as ejection fraction after the AV node ablation. Third, the small sample size constrains statistical power, which may both reduce the probability of finding an effect and exaggerate the magnitude of the effect found. And last, our highly selected population restricts the extrapolation of our results. On the contrary, the study of this peculiar population allows us to differentiate the chronotropic effects from the rest of the cardiovascular effects of BB.

5 Conclusions

These results demonstrate that the use of BB in patients with a pacemaker rhythm after an AV node ablation is associated with an increased risk of hospitalizations for HF. More studies are needed to clarify the precise role of BB in patients with different types of HF and of cardiac rhythm disturbances.

References

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHX393.

McDongagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3599–726. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab368.

Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612.

Cleland JGF, Bunting KV, Flather MD, et al. Beta-blockers for heart failure with reduced, mid-range, and preserved ejection fraction: an individual patient-level analysis of double-blind randomized trials. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(1):26–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/EURHEARTJ/EHX564.

Koteka D, Holmes J, Krum H, et al. Efficacy of β blockers in patients with heart failure plus atrial fibrillation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis. Lancet (London, England). 2014;384(9961):2235–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61373-8.

Korantzopoulos P, Letsas KP, Grekas G, Goudevenos JA. Pacemaker dependency after implantation of electrophysiological devices. Europace. 2009;11(9):1151–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/eup195.

Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496. https://doi.org/10.2307/2670170.

Famoye F. On the bivariate negative binomial regression model. J Appl Stat. 2010;37(6):969–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664760902984618.

Bertomeu-González V, Núñez J, Núñez E, et al. Heart rate in acute heart failure, lower is not always better. Int J Cardiol. 2010;145(3):592–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.05.076.

Bunch TJ, May HT, Afshar K, Alharethi R, Day JD. Mechanisms of improved mortality following ablation: does ablation restore beta-blocker benefit in atrial fibrillation/heart failure? Cardiol Clin. 2019;37(2):177–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2019.01.011.].

Silverman DN, Plante TB, Infeld M, et al. Association of β-Blocker use with heart failure hospitalizations and cardiovascular disease mortality among patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction: a secondary analysis of the TOPCAT trial. JAMA Netw open. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2019.16598.

Borlaug BA, Anstrom KJ, Lewis GD, et al. Effect of inorganic nitrite vs placebo on exercise capacity among patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the INDIE-HfpEF randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(17):1764–73. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2018.14852.

Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Rehospitalization for heart failure: predict or prevent? Circulation. 2012;126(4):501–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.125435.

Amin AN, Jhaveri M, Lin J. Hospital readmissions in US atrial fibrillation patients: occurrence and costs. Am J Ther. 2013;20(2):143–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0B013E3182512C7E.

Braunschweig F, Cowie MR, Auricchio A. What are the costs of heart failure? Europace. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/EUROPACE/EUR081.

Nagatomo T, Abe H, Kikuchi K, Nakashima Y. New onset of pacemaker dependency after permanent pacemaker implantation. PACE Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2004;27(4):475–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00466.x.

Sood N, Crespo E, Friedman M, et al. Predictors of pacemaker dependence and pacemaker dependence as a predictor of mortality in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator. PACE Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2013;36(8):945–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/pace.12164.

Barsheshet A, Moss AJ, McNitt S, et al. Long-term implications of cumulative right ventricular pacing among patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Hear Rhythm. 2011;8(2):212–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HRTHM.2010.10.035.

Tang ASL, Roberts RS, Kerr C, et al. Relationship between pacemaker dependency and the effect of pacing mode on cardiovascular outcomes. Circulation. 2001;103(25):3081–5. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.103.25.3081.

Takemoto Y, Hozumi T, Sugioka K, et al. Beta-blocker therapy induces ventricular resynchronization in dilated cardiomyopathy with narrow QRS complex. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(7):778–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.081.

Tops LF, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ. The effects of right ventricular apical pacing on ventricular function and dyssynchrony. Implications for therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(9):764–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.006.

Packer M, Coats AJS, Fowler MB, et al. Effect of carvedilol on survival in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(22):1651–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200105313442201.

Wang Y, Wang Y, Yang D, et al. β1-adrenoceptor stimulation promotes LPS-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through activating PKA and enhancing CaMKII and IκBα phosphorylation. Crit Care. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0820-1.

Sugioka K, Hozumi T, Takemoto Y, et al. Early recovery of impaired coronary flow reserve by carvedilol therapy in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: a serial transthoracic Doppler echocardiographic study [1]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(2):318–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.019.

Ciccarelli M, Sorriento D, Coscioni E, Iaccarino E, Santulli G. Adrenergic receptors (chapter 11). In: Schisler JC, Lang CH, Willis MS, editors. Endocrinology of the heart in health and disease. New York: Academic Press; 2017. p. 285–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803111-7.00011-7.

Williams B, Lacy PS, Thom SM, et al. Differential impact of blood pressure-lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes: principal results of the Conduit Artery Function Evaluation (café) study. Circulation. 2006;113(9):1213–25. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595496.

Nambiar L, Meyer M. β-Blockers in myocardial infarction and coronary artery disease with a preserved ejection fraction: recommendations, mechanisms, and concerns. Coron Artery Dis. 2018;29(3):262–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCA.0000000000000610.

Stanek B, Frey B, Hülsmann M, et al. Prognostic evaluation of neurohumoral plasma levels before and during beta-blocker therapy in advanced left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(2):436–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01383-3.

Myhre PL, Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, et al. Association of natriuretic peptides with cardiovascular prognosis in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: secondary analysis of the TOPCAT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(10):1000–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMACARDIO.2018.2568.

Kotecha D, Flather MD, Altman DG, et al. BetaBlockers in Heart Failure Collaborative Group. Heart rate and rhythm and the benefit of beta-blockers in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2885–96.

Mareev Y, Cleland JG. Should β-blockers be used in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation? Clin Ther. 2015;37(10):2215–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.08.017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. No external funding was used in the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interests/competing interest

Vicente Bertomeu-Gonzalez, Jose Moreno-Arribas, Santiago Heras, Nerea Fernandez-Ortiz, Diego Cazorla, María Amparo Quintanilla, Jose Maria Lopez-Ayala, Lorenzo Facila, Pilar Zuazola and Alberto Cordero declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this article.

Ethics approval

The local institutional ethics committee approved the study, which conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

VB-G: conceived and designed the analysis. JM-A: collected. SH: collected the data. NF-O: contributed data or analysis tools. DC: contributed data or analysis tools. MAQ: wrote the paper. JML-A: wrote the paper. LF: conceived and designed the analysis. PZ: conceived and designed the analysis. AC: performed the analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertomeu-Gonzalez, V., Moreno-Arribas, J., Heras, S. et al. Increased Risk of Heart Failure in Elderly Patients Treated with Beta-Blockers After AV Node Ablation. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 23, 157–164 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-022-00566-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-022-00566-1