Abstract

First-principles molecular dynamics simulations have been employed to analyse the proton diffusion in cubic BaZrO\(_3\) perovskite at 1300 K. A non-linear effect on the proton diffusion coefficient arising from an applied isometric strain up to 2 \(\%\) of the lattice parameter, and an evident enhancement of proton diffusion under compressive conditions have been observed. The structural and electronic properties of BaZrO\(_3\) are analysed from Density Functional Theory calculations, and after an analysis of the electronic structure, we provide a possible explanation for an enhanced ionic conductivity of this bulk structure that can be caused by the formation of a preferential path for proton diffusion under compressive strain conditions. By means of Nudged Elastic Band calculations, diffusion barriers were also computed with results supporting our conclusions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The development of highly ionic conductive materials is of particular importance for the fabrication of high-performance solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) operating at intermediate temperatures (550–900 K). State-of-the-art SOFC technology requires the cell to operate at temperatures between 1000 and 1300 K, which makes both fabrication and operation costly because expensive materials need to be used for sealing and for inter-connectors [1, 2]. Therefore, to encourage widespread adoption of SOFCs, the development of highly conductive materials that can operate at intermediate temperatures is imperative.

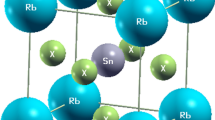

BaZrO\(_3\), similar to several other compounds that crystallize in a perovskite structure, shows high proton conductivity and is, therefore, a good candidate for an electrolyte material capable of operation at the desired operating temperature [3]. Ideally, in a perfect perovskite structure, a proton forms an O–H bond with one of the oxygen atoms, where the O–H group is characterized by its vibrational and rotational motion. The proton conduction mechanism has been described in terms of proton jumps from one oxygen site to another by H transfer and O–H reorientation [4, 5]. Because of the lattice geometry, the possible jumps are classified as intra-octahedral or inter-octahedral [6]. At its stable site, the hydrogen atom interacts strongly with the surrounding atoms; this interaction deforms the lattice by shortening the distance between the proton and the neighbouring oxygen. Migration occurs through a series of transitions between sites coordinated to different oxygens and sites coordinated to the same oxygen [7, 8]. The proton jump and O–H reorientation are schematically illustrated in Fig. 1.

It is also well known that ionic conductivity can be higher in doped perovskites where one or more cations of the host crystal is substituted with lower valence cations [2, 9]. A charge redistribution occurs after doping to balance the different oxidation states of the dopant and the substituted atom. This can create oxygen vacancies in the lattice. If the crystal is in contact with a humid environment, water molecules occupy the vacancies and dissociate, increasing the concentration of interstitial protons in the lattice and thereby the conductivity. This may, however, be reduced by traps produced by the dopants, as described by Yamazaki et al. [10] in Ref. 10. Furthermore, an additional and non-negligible effect of doping is a local distortion and the breaking of the lattice symmetry. This effect contributes to the creation of new oxygen transport pathways; the local distortion stretches the bond, affecting the activation barriers and the diffusivity of the species. First-principles molecular dynamics simulations have been widely used to calculate and predict the ion conduction properties of several bulk crystal structures, confirming this migration mechanism [11, 12].

In addition to describing a new class of compounds, the latest studies highlight the significant increase in conductivity that can be achieved by coupling metal oxide materials having different lattice parameters. This would create a so-called semi-coherent interface at which the two compounds are subjected to strain, although the role of strain on the ionic conductivity has been recently questioned [13, 14, 15]. A semi-coherent interface preserves the crystal structure of the original compound while creating a deformation of the cell, which, however, preserves its original volume. In the cubic perovskite structure, the deformation would result in an interface strain (epitaxial strain) that would produce a tetragonal structure with the same volume as the original cubic one. Within this framework, it is essential to study the effect of strain on ion diffusion to develop a new class of electrolyte materials with good chemical stability and high ion conductivity in the intermediate-/low-temperature range.

In this work, we analysed the effect of external strain on proton diffusion in the cubic perovskite crystal structure of BaZrO\(_3\) to estimate the conditions under which proton conduction might be enhanced. Here, we considered only isotropic strains to avoid the existence of a preferential diffusion direction. We use a first-principles molecular dynamics approach, within the Car–Parrinello approximation, with a temperature of 1300 K. The choice of the temperature has been made to facilitate the diffusion process if compared to the typical intermediate temperature of a SOFC. For temperature between 550 and 1300 K, the physical properties of the lattice and proton diffusion would differ quantitatively, but there will be no difference in the mechanism. The elevated temperature was also chosen to increase the computational efficiency of the simulations, due to the increase in ion mobility and proton diffusion at this temperature, without affecting the significance of the results. In practical applications, barium zirconate is doped to facilitate the formation of the oxygen vacancies, which are necessary to allow proton incorporation and diffusion. However, in the present work, we analyse only the pure BaZrO\(_3\) crystal because we focus on analysing the effect of strain on proton diffusion. We focus in this study on the trapping-free conductivity by investigating undoped BaZrO\(_3\). Specifically, we want to analyse the effect of strain on the proton diffusivity, independently from trapping. Work on doped BaZrO\(_3\) forms the basis of a separate study outside the scope of this paper.

Schematic representation of proton diffusion, highlighting proton reorientation and proton transfer movements. The H atom bonded to the O atom migrates to the next oxygen atom, breaking a O–H bond and forming a new one. The proton can reorient on an oxygen site to facilitate the next jump. The picture shows the octahedron polyhedrons formed by oxygen atoms, and paths for proton diffusion through intra- and inter-octahedral jumps

Calculation methods

Conditions for electronic states calculations

We used plane-wave basis density functional theory (DFT) as implemented in the Car–Parrinello code of the Quantum-ESPRESSO distribution [16]. We used a Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional for the exchange-correlation term [17]. Ultrasoft pseudo-potentials were used to simulate the effect of the core electrons. Eight and twelve valence electrons in the 6s\(^2\)5p\(^6\)5s\(^2\) and 5s\(^2\)4d\(^2\)4p\(^6\)4s\(^2\) configurations were considered for barium and zirconium atoms, respectively, and six electrons in 2p\(^4\)2s\(^2\) were considered for oxygen atoms. \(\Gamma \) point sampling of the Brillouin zone was employed, while for Nudged Elastic Band calculation a (2 \(\times \) 2 \(\times \) 2) grid has been employed, and the cutoff energies for the wave function and charge density were 27.0 and 240 Ry, respectively [18].

The calculation was considered to be converged when the force on each ion was less than \(10^{-3}\) eV/Å with a convergence in the total energy of \(10^{-5}\) eV, while for Nudged Elastic Band calculation value of the norm of the forces orthogonal to the path is less than \(10^{-2}\) eV/Å.

Conditions for dynamics calculations

We performed Car–Parrinello molecular dynamics simulations. The simulations were performed in super-cells of BaZrO\(_3\) with 40 and 135 atoms (symmetry group Pm\(\overline{3}\)m) and in the canonical ensemble. To simulate the target temperature a Nosé–Hoover thermostat at 1300 K has been used. The runs, each lasting between 40 and 50 ps, were performed using a fictitious electron mass m = 150 a.u. and a time step dt \(=\) 0.21 fs. These choices allow for excellent conservation of the constant of motion (Fig. 2 a shows negligible dissipation during a typical 46 ps simulation) and negligible drift in the fictitious kinetic energy of the electrons for simulations of that duration. In addition, the ratio between the kinetic energies of ions and electrons was R < 1/20 for the entire simulation time, as shown in Fig. 2b. The separation between the ionic and wave function kinetic energies in Fig. 2b indicates a good approximation for the fictitious electron mass. We discarded from each trajectory the initial 4 ps, during which the ions reached their target kinetic energy. To calculate the BaZrO\(_3\) average lattice constant at T \(=\) 1300 K, variable cell simulations were performed in a 135-atom super-cell in isothermal–isobaric ensemble, with an external pressure imposed at 10\(^{-3}\) kbar.

The top and the bottom panels represent, respectively, the potential energy and constant of motion (blue and green lines, respectively), and the ionic and wave function kinetic energy (red and black lines). The simulation was performed in a 40-atom super-cell where the temperature of the simulations was maintained at 1300 K by a Nosé–Hoover thermostat. The fictitious electron mass is 150 a.u. and the time step dt \(=\) 0.21 fs

Hydrogen charge treatment

Björketun et al. studied the charge state of the hydrogen atom [19]. Using DFT calculations, they estimated the interstitial hydrogen atom formation energy as a function of the Fermi energy. Their results showed that the hydrogen atom is stable in the charge state +1 (the proton) for every value of the Fermi energy within the band gap range [19]. Therefore, in this work we considered only the diffusion of the positive charge state of the hydrogen (the proton), and a compensating jellium background was inserted in the calculations to remove divergences due to the positive charged cell in the calculations. We calculate the hydrogen defect formation energy as follows:

where \(E^\mathrm{bulk}_\mathrm{H}\) and \(E^\mathrm{bulk}\) are the energy of the hydrogenated and stoichiometric BaZrO\(_3\), respectively, while q is the charge of the system, \(\mu _\mathrm{H}\) is the chemical potential of the hydrogen atom, \(\mu _\mathrm{e}\) is the chemical potential of the electrons (Fermi energy). We obtained a value of 0.18 eV in a relaxed super-cell (40 atoms) calculated when the Fermi level is at the valence band maximum, whereas \(\mu _\mathrm{H}\) is defined as one half of the total energy of a hydrogen molecule in vacuum. For BaZrO\(_3\) cubic perovskite, this value has been calculated in Ref. [19] in relaxed super-cells to be 0.05 eV (in a 2 \(\times \) 2 \(\times \) 2 super-cell) and 0.21 eV (in a 3 \(\times \) 3 \(\times \) 3 super-cell). Thus, our results are consistent with Ref. [19].

Results

We obtained a value of 4.21 Å for the relaxed lattice constant of the stoichiometric BaZrO\(_3\) bulk by cell optimization at T = 0 K; this is consistent with other DFT studies (4.20 Å) and with the experimental value (4.19 Å) [20, 21]. After a proton is introduced into the relaxed bulk 40-atom super-cell and for the cell under tensile strain and compression, relaxation yields an O–H bond distance of 0.98 Å. The positively charged region surrounding the proton produces a structural distortion compared to the stoichiometric BaZrO\(_3\) bulk with a Zr–O–Zr angle of 162.55\(^{\circ }\) (180.00\(^{\circ }\) in the stoichiometric bulk).

We analysed the effect of temperature on the lattice parameter expansion by calculating the average change in the cell parameter as a function of time at T = 1300 K, as illustrated in Fig. 3. We simulated the BaZrO\(_3\) stoichiometric bulk allowing a variable cell size, starting with a thermally expanded lattice parameter, as reported by experimental measurements, to estimate the effect of the temperature on the lattice parameter and the relative expansion coefficient [22]. The calculated average lattice constant in a variable cell simulation at T = 1300 K was 4.236 Å, and the calculated expansion coefficient was Ec = 5.4 \(\times \) 10\(^{-6}\) K\(^{-1}\); experimental data in the literature report a value of 7.8 \(\times \) 10\(^{-6}\) K\(^{-1}\), suggesting a 0.04 Å expansion of the lattice parameter [22]. To simulate an applied external strain (either tensile or compressive), we applied a variation of ±2 \(\%\) (0.10 Å) to the thermally expanded lattice parameters, which corresponds to a pressure of ca. ±5 Gpa. The simulations for proton diffusion were run at a constant lattice parameter for the relaxed bulk and under compressive or tensile strain.

For each condition, we calculated the mean square displacement (MSD) of the proton during simulations of 40–50 ps [23]. The MSD can be calculated from a single trajectory by only performing a time average. Each curve is, therefore, a time-average calculation over a single trajectory. Here, we considered the average value of the MSD of the proton during self-diffusion over different time lengths, as shown in Fig. 4 for the relaxed bulk. An average over N = 11,000 time steps yields a linear relationship between the MSD and time, which is consistent with other works in the literature [24, 25]. To have a measure of the accuracy when MSD averages were calculated, we compute the Haven ratio (\(H_\mathrm{R}\)) for MSD averages over different time length, where \(H_\mathrm{R}\) is defined as follows:

Here, \(D{_i}{^*}\) is the tracer diffusion coefficient and \(D{_i}(\sigma {_i})\) the conductivity diffusion coefficient of particle i. We calculated that the Haven ratio by averaging the MSD over 10,000 time steps is 1.46 times that by averaging over 7000 time steps, which increases significantly the precision of the calculations. The Haven ratio calculated by averaging over 11,000 time steps is 1.04 times of that calculated from 10,000 time steps.

Next, we calculated the self-diffusion coefficient (D) from the MSD using the Einstein relation:

where r is the position of the proton at each time step t. In the relaxed bulk, the calculated diffusion coefficient was 2.3 ± 0.3 \(\times \) 10\(^{-5}\) cm\(^2\)/s. This value can be compared with other computational work in the literature [26, 10]. Although no explicit evaluation at 1300 K has been done, Ref. [10] uses a reactive force field approach to a calculated diffusion coefficient of ca. 1.5 \(\times \) 10\(^{-5}\) cm\(^2\)/s for the relaxed bulk at 1300 K [10]. Yamazaki et al. measured proton diffusion in yttrium-doped BaZrO\(_3\) by impedance spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis and they found a trapping mechanism, due to the yttrium atoms, to coexist with a trap-free diffusion mechanism. They were able to extrapolate the trap-free proton diffusion coefficient and they reported it to be 3 ± 2 \(\times \) 10\(^{-5}\) cm\(^2\)/s at 1000 K, which can be extrapolated to 1.0 ± 2.0 \(\times \) 10\(^{-5}\) cm\(^2\)/s at 1300 K, in line with our results [10].

The D values, calculated by extracting the coefficient of a linear regression of the MSD curves shown in Fig. 5, were 2.2 ± 0.3\(~\times \) 10\(^{-5}\) and 3.5 ± 0.3\(~\times \) 10\(^{-5}\) cm\(^2\)/s, respectively, for the bulk under tensile and compressive strain. Given the accuracy of the calculation of D, this change is significant, and the proton diffusivity under compressive strain is enhanced compared with the other two conditions, resulting in a total path-length of 9.16 \(\times \) 10\(^{-4}\) cm after 40 ps, where the same value is 7.43 \(\times \) 10\(^{-4}\) cm under relaxed conditions. These results show that the change in the lattice parameter under uniform compressive strain does not result in a linear variation of the proton diffusivity. By way of explanation, when a tensile strain is applied to the relaxed bulk, D does not change significantly, whereas a compression of the same length clearly increases D.

Power spectrum of calculated proton diffusion in the fully relaxed BaZrO\(_3\) bulk. The spectrum was obtained by Fourier transform of the velocity–velocity correlation function. The high wave number peak is consistent with that of the O–H bond in water at around 3600 cm\(^{-1}\), while the peak at low wave number resembles that measured by Karlsson et al in similar systems [28]

To understand the origin of this effect, we analysed the typical vibration frequencies of the proton, the typical O–H distances, and the electronic structure of the system under different strain conditions. We analysed the typical vibration frequency of the proton by performing a Fourier transform of the velocity–velocity correlation function (ACF), which was calculated in the x–y–z coordinates (Fig. 6). While the diffusion coefficient extrapolated from the MSD gives insights into the total displacement, the Fourier transform of the ACF shows two distinct peaks clearly corresponding to distinct diffusion mechanisms, which are attributed to rotation and transfer. The peak at 700–900 cm\(^{-1}\) represents the frustrated reorientation of the O–H axis, while that at 3500–3700 cm\(^{-1}\) represents the O–H stretching vibration (see Fig. 1). Interestingly, the frustrated reorientation peak splits into two parts, consistent with the crystal symmetry. Both peaks are in good agreement with infrared spectroscopy and inelastic neutron scattering analysis (see Refs. [29, 28, 30]), and in line with the one calculated with the same methodology in similar perovskites by Shimojo et al. (see Ref. [12]); however, no substantial change in the power spectrum was observed under tensile or compressive strain.

We calculated the pair correlation function (g(r)) to evaluate how the probability of finding an oxygen atom changes with the distance from the proton and with the distance from another oxygen atom. Considering the statistical error, which results in a broadening of the peaks, the three cases do not show qualitative differences in the oxygen–oxygen radial distribution, with a clear peak around 3.00 Å and a second peak around 4.10–4.30 Å (Fig. 7). We observe only minor differences in the peak positions arising from the effect of the applied strain that slightly modifies atomic distances. On the other hand, in the proton–oxygen distribution, a clear peak appears at around 1.00 Å, indicating binding of the proton to oxygen; a second peak appears at different distances in the three cases. When the bulk is fully relaxed, the pair correlation function shows a broad peak around 3.12–3.16 Å, and this peak is reduced under tensile strain. Under compressive strain, a pronounced peak appears around 3.12–3.16 Å, with a new peak appearing around 2.40 Å (Fig. 8). Since this feature is broad and shows a higher intensity, it indicates an enhanced probability of finding a second oxygen atom close to the proton, suggesting that there is a further interaction of the proton with a second oxygen atom (O\(_B\) in Fig. 9) in addition to the original O–H bond (O\(_A\) in Fig. 9), as supposed in experimental works [31]. In Ref. [31], it is stated that since the hopping rate decreased rapidly as the O–O separation is increased, the reduced diffusion of protons across the grain boundary may arise from the increased average distances between oxygen atoms in the interface. This confirm our results that link the magnitude of proton diffusion with the O–O, and the O–H distances calculated from the pair correlation function.

a Schematic representation of proton equilibrium position before diffusion. During diffusion, the H atom bonded to the O\(_A\) atom migrates to the next oxygen atom, breaking the O\(_A\)–H bond and forming a new O\(_B\)–H bond. b, c Energy configuration during proton diffusion, calculated by using the Nudged Elastic Band method, as a function of the reaction coordinate under tensile and compressed conditions, respectively. For these calculations, the 40-atom super-cell has been used

Projected density of states (PDOS) of BaZrO\(_3\) a under relaxed stoichiometric conditions, b after introduction of a proton under relaxed conditions, and after introduction of a proton under c compressive and d tensile strain. In the plots, the Fermi energy is positioned at 0 eV. The valence band maximum lies below E\(_\mathrm{F}\) and conduction band minimum lies above E\(_\mathrm{F}\)

We found a substantial difference in the electronic structure of the relaxed, compressed, and strained bulk BaZrO\(_3\). In the absence of a proton, all oxygen atoms are structurally and chemically identical. The introduction of the proton then breaks the local symmetry of the oxygen sites, giving a modified electronic structure when compared to pure BaZrO\(_3\). The projected density of states (PDOS) shows a strong O\(_A\)–H bond (Fig. 10b) formed by hybridization of the H\(_{1s}\) and O\(_{2p}\) states that peaks around −8.3 eV. In addition, a second peak representing the oxygen 2p state of O\(_A\) around −6.3 eV and some contribution to the upper valence band appears. When the bulk is under compressive strain, the PDOS shows the interaction of the H\(_{1s}\) with a second (next-nearest O\(_B\) in Fig. 10c) oxygen atom around \(-7.9\) eV, suggesting the origin of a hybridization of the proton with another oxygen atom, consistent with the pair correlation function of the proton. In the bulk under tensile strain, this type of hybridization does not appear (Fig. 10d). This analysis suggests that lattice compression induces an interaction between H and a second O that is not present in the original structure or with the tensile strain. The electronic structure analysis, together with the analysis of the g(r), suggests the formation of a favourable path for proton diffusion under compressed conditions that facilitates proton migration.

The appearance a proton–oxygen interaction is also suggested by the O\(_B\)–H distances for the next-nearest oxygen atom O\(_B\) in the relaxed, compressed and strained structures. Using GGA-DFT calculations, we optimized these structures and found an O\(_B\)–H distance of 2.13 Å in the fully relaxed bulk and in the bulk under tensile strain. Thus, the geometry of the structure under tensile strain is qualitatively similar to that of the relaxed bulk. The same distance is 1.63 Å under compression, which is comparable to the typical O–H hydrogen bond distance in liquid water and appears due to the compressive strain allowing an interaction between proton and O\(_B\). In addition, under compression, the two oxygen atoms O\(_A\) and O\(_B\) show a shorter O–O distance (of 2.51 Å) if compared with the other two conditions. However, this is a purely local effect due to the positive charge of the proton, which is not reflected in the average O–O distance shown in Fig. 7.

Finally, we analysed the charge redistribution after protonation of the bulk structures. We calculated the charge redistribution by taking the difference between the charge distributions of the stoichiometric and protonated bulk. In the compressed bulk, we found a quasi-symmetric charge distribution around the proton in the direction of two neighbouring oxygens, suggesting the presence of a second (weaker) O–H interaction discussed above, in addition to the structural O–H bond (Figs. 11b, d). The quasi-symmetrical charge distribution and the resemblance of the O\(_B\)–H to the O\(_A\)–H bond did not appear in the relaxed or tensile strained structure (Figs. 11a, c) and confirm the formation of a natural pathway in the compressed structure that facilitates proton diffusion. The change of the electronic structure and the appearance of a new O–H interaction suggests a lower activation energy of the proton jump if compared with the tensile or no strain conditions.

Our calculated activation barriers (\({E_\mathrm{b}}\)) for proton migration (O\(_A\)–H to O\(_B\)–H in Fig. 9 a), whose correlation with the bond length has been confirmed in other computational works (see Refs. [32, 33, 34]), support these findings: under relaxed condition \({{E_\mathrm{b}}}=\)0.60 eV, while under tensile strain condition \({{E_\mathrm{b}}}=\)0.62 eV and compressive stain conditions \({E_\mathrm{b}}=\)0.50 eV (Fig. 9b, c). The diffusion barrier measured by Yamazaki et al. at low temperature is 0.46 eV, while the extrapolated value at indefinitely high temperature (associated to a trap-free diffusion) is 0.17 eV [10]. Our calculated trap-free diffusion barriers are relatively higher then the one extrapolated by Yamazaki et al.; however, here we intend to show the relative change in proton diffusion under different conditions; therefore, the main focus is the relative change rather than the absolute value. In addition, the proton migration barrier values calculated for the relaxed conditions in the present work lie in the range of values found in the literature, with reported values between 0.20 and 0.83 eV [35, 6, 8, 20, 20]. Such a large range might be due to the different setup used in different works (e.g. Björketun et al. in Ref. [35] use a different GGA functional), to which NEB calculations are very sensitive.

We also calculate the barriers for a 90\(^{\circ }\) rotation of the proton around oxygen ions, and we find these to be 0.06, 0.04 and 0.12 eV for the relaxed, tensile strained and compressed conditions, respectively. While these barriers do show an opposite trend compared to the trend for proton migration, their magnitude is significantly lower and they will not result in any significant decrease in proton diffusion.

Our conclusion may appear to contradict the experimental evidence of Chen et al., which shows an enhanced proton mobility in hydrated conditions, where a BaZr\(_{0.9}\)Y\(_{0.1}\)O\(_3\) shows larger lattice parameter due to the hydrostatic pressure induced by the syntheses route [36]. The discrepancies may be due to several differences in the system and the environmental conditions, such as the hydrated conditions, under which the experiment has been performed, which means that water is present and hydroxyls can form, do not resemble our simulated conditions [37, 38]. However, Ottochan et al. analysed proton conduction in Yttrium-doped BaZrO\(_3\) under biaxial compressive conditions through the use of reactive molecular dynamics simulations. They conclude that compressive pressure should lead to an increase in the proton diffusion coefficient by shortening the oxygen–oxygen distance, which confirm our results supporting our conclusions [39].

Conclusions

We applied Car–Parrinello Molecular Dynamics to investigate proton diffusion in the undoped BaZrO\(_3\) cubic perovskite bulk crystal under fully relaxed, isometric tensile strain and compressive strain conditions. The analysis of the MSD indicates that an applied external strain has a non-linear effect on the proton diffusion constant, and we found that there is an evident enhancement of proton diffusion under compressive strain, whereas there is no difference between the relaxed bulk crystal and that under tensile strain. The power spectrum obtained by a Fourier transform of the velocity–velocity autocorrelation function showed two main peaks, one of which (ca. 3600 cm\(^{-1}\)) is likely to indicate the O–H stretching mode, while the other (ca. 700–900 cm\(^{-1}\)) indicates the frustrated rotational mode. However, no obvious differences appeared under either tensile or compressive strain.

We calculated the oxygen–oxygen and proton–oxygen pair correlation functions and found a significant difference in the latter under compression compared to the other two conditions, which suggests the origin of a second O–H interaction, in addition to the original O–H bond. The PDOS show a significant difference between the electronic structure of the protonated compressed bulk when compared to other systems, where there is an evident overlap of the H\(_{1s}\) with two neighbouring O\(_{2p}\) confirming the formation of a second O–H interaction. Finally, the analysis of the charge redistribution after the introduction of a proton into the structures also supports this hypothesis indicating the formation of a pathway that facilitates proton diffusion only in compressed BaZrO\(_3\) bulk.

References

Steele, B.C., Heinzel, A.: Materials for fuel-cell technologies. Nature 414, 345 (2001)

Aguadero, A., Fawcett, L., Taub, S., Woolley, R., Wu, K.-T., Xu, N., Kilner, J.A., Skinner, S.J.: Materials development for intermediate-temperature solid oxide electrochemical devices. J. Mater. Sci. 47, 3925 (2012)

Fabbri, E., Pergolesi, D., Traversa, E.: Materials challenges toward proton-conducting oxide fuel cells: a critical review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 4355 (2009)

Zhang, Q., Wahnström, G., Björketun, M.E., Gao, S., Wang, E.: Path Integral Treatment of Proton Transport Processes in BaZrO\(_3\). Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 215902 (2008)

Sundell, P.G., Björketun, M.E., Wahnström, G.: Density-functional calculations of prefactors and activation energies for H diffusion in BaZrO\(_3\). Phys. Rev. B. 76, 094301 (2007)

Munch, W., Kreuer, K.D., Seifert, G., Maier, J.: Proton diffusion in perovskites: comparison between O\(_3\), BaZrO\(_3\), SrTiO\(_3\) and CaTiO\(_3\) using quantum molecular dynamics. Solid State Ion. 136, 183 (2000)

Cherry, M., Islam, M.S., Gale, J.D., Catlow, C.: Computational studies of proton migration in perovskite oxides. Solid State Ion. 77, 207 (1995)

Gomez, M.A., Griffin, M.A., Jindal, S., Rule, K.D., Cooper, V.R.J.: The effect of octahedral tilting on proton binding sites and transition states in pseudo-cubic perovskite oxides. Chem. Phys. 123, 094703 (2005)

Madhavanand, B., Ashok, A.: Review on nanoperovskites: materials, synthesis, and applications for proton and oxide ion conductivity. Ionics 21, 601 (2015)

Yamazaki, Y., Blanc, F., Okuyama, Y., Buannic, L., Lucio-Vega, J.C., Grey, C.P., Haile, S.M.: Proton trapping in yttrium-doped barium zirconate. Nat. Mat. 12, 647 (2013)

Marrocchelli, D., Madden, P.A., Norberg, S.T., Hull, S.: Cation composition effects on oxide conductivity in the Zr\(_2\)Y\(_2\)O\(_7\)–Y\(_3\)NbO\(_7\) system. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 405403 (2009)

Shimojoand, F., Hoshino, K.: Microscopic mechanism of proton conduction in perovskite oxides from ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. Solid State Ion. 145, 421 (2001)

Garcia-Barriocanal, J., Rivera-Calzada, A., Varela, M., Sefrioui, Z., Iborra, E., Leon, C., Pennycook, S.J., Santamaria, J.: Colossal ionic conductivity at interfaces of epitaxial ZrO\(_2\):Y\(_2\)O\(_3\)/SrTiO\(_3\). Science 321, 676 (2008)

Korte, C., Peters, A., Janek, J., Hesse, D., Zakharov, N.: Ionic conductivity and activation energy for oxygen ion transport in superlattices—the semicoherent multilayer system YSZ (ZrO\(_2\) \(+\) 9.5 mol% \(Y_2O_3)/Y_2O_3\) (2008)

Pergolesi, D., Fabbri, E., Cook, S., Roddatis, V., Traversa, E., Kilner, J.: Tensile lattice distortion does not affect oxygen transport in yttria-stabilized zirconia-CeO\(_2\). ACS Nano 6, 10524 (2012)

Giannozzi, P., Baroni, S., Bonini, N., Calandra, M., Car, R., Cavazzoni, C., Ceresoli, D., Chiarotti, G.L., Cococcioni, M., Dabo, I.: QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantumsimulations of materials. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009)

Perdew, J.P., Burke, K., Ernzerhof, M.: Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett 77, 3865 (1996)

Bilić, A., Gale, J.D.: Ground state structure of BaZrO\(_3\): a comparative first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 79, 174107 (2009)

Björketun, M.E., Sundell, P.G., Wahnström, G.: Structure and thermodynamic stability of hydrogen interstitials in BaZrO\(_3\) perovskite oxide from density functional calculations. Faraday Discuss. 134, 247 (2007)

Shi, C., Yoshino, M., Morinaga, M.: First-principles study of protonic conduction in In-doped AZrO\(_3\) (A = Ca, Sr, Ba). Solid State Ion. 176, 1091 (2005)

Pagnier, T., Charrier-Cougoulic, I., Ritter, C., Lucazeau, G.: A neutron diffraction study of BaCe\(_x\) \({\rm Zr}_{1-x}O_3\). Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 9, 1 (2000)

Zhaoand, Y., Weidner, D.J.: Thermal expansion of SrZrO\(_3\) and BaZrO\(_3\) perovskites. Phys. Chem. Miner. 18, 294 (1991)

Ebeling, W.: Nonlinear Brownian motion-mean square displacement. Condens. Matter Phys. 7, 539 (2004)

Wangand, J., Hou, T.: Application of molecular dynamics simulations in molecular property prediction II: diffusion coefficient. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 3505 (2011)

Sitand, P.H.-L., Marzari, N.: Static and dynamical properties of heavy water at ambient conditions from first-principles molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 204510 (2005)

Kitamura, N., Akoala, J., Kohara, S., Fujimoto, K., Idemoto, Y.: Proton Distribution and Dynamics in Y- and Zn-Doped BaZrO\(_3\). J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 18846 (2014)

Raiteri, P., Gale, J.D., Bussi, G.: Reactive force field simulation of proton diffusion inBaZrO\(_3\) using an empirical valence bond approach. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 23, 334213 (2011)

Karlsson, M., Matic, A., Parker, S.F., Ahmed, I., örjesson, L.B., Eriksson, S.: O–H wag vibrations in hydrated \({\rm Baln}_x\) \({\rm Zr}_{1-x}O_{3-x/2}\) investigated with inelastic neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. B 77:104302 (2008)

Kreuer, K.D.: Aspects of the formation and mobility of protonic charge carriers and the stability of perovskite-type oxides. Solid State Ion. 125, 285 (1999)

Karlsson, M., Björketun, M.E., Sundell, P.G., Matic, A., Wahnström, G., Engberg, D., Börjesson, L.: Vibrational properties of protons in hydrated \({\rm Baln}_x\) \(Zr_{1-x}O_{3-x/2}\). Phys. Rev. B 72:094303 (2005)

van Duin, A.C.T., Merinov, B.V., Han, S.S., Dorso, C.O., Goddard III, W.A.: ReaxFF reactive force field for the Y-doped BaZrO\(_3\) proton conductor with applications to diffusion rates for multigranular systems. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 11414 (2008)

Kreuer, K.D.: Proton conductivity: materials and applications. Chem. Mater. 8, 610 (1996)

Kreuer, K.D.: Proton-conducting oxides. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 33, 333 (2003)

Merinov, B., Goddard III, W.: Proton diffusion pathways and rates in Y-doped BaZrO\(_3\) solid oxide electrolyte from quantum mechanics. J. Chem. Phys. 130, 194707 (2009)

Sundell, P.G., Björketun, M.E., Wahnström, G.: Density-functional calculations of prefactors and activation energies for H diffusion in BaZrO\(_3\). Phys. Rev. B. 76, 0543.7 (2007)

Chen, Q., Braun, A., Ovalle, A., Savaniu, C.-D., Graule, T., Bagdassarov, N.: Hydrostatic pressure decreases the proton mobility in the hydrated BaZr\(_{0.9}\)Y\(_{0.1}\)O\(_3\). Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 041902 (2010)

Shu, D.-J., Ge, S.-T., Wang, M., Ming, N.-B.: Interplay between external strain and oxygen vacancies on a rutile TiO\(_2\)(110). Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 116102 (2008)

Cammarata, A., Ordejón, P., Emanuele, A., Duca, D.: Y:BaZrO\(_3\) Perovskite compounds I: DFT study on the unprotonated and protonated local structures. Chem. Asian J. 7, 1827 (2012)

Ottochian, A., Dezanneau, G., Gilles, C., Raiteri, P., Knight, C., Gale, J.: Influence of isotropic and biaxial strain on proton conduction in Y-doped BaZrO\(_3\): a reactive molecular dynamics study. J. Mater. Them. A 2, 3127 (2014)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fronzi, M., Tateyama, Y., Marzari, N. et al. First-principles molecular dynamics simulations of proton diffusion in cubic BaZrO\(_3\) perovskite under strain conditions. Mater Renew Sustain Energy 5, 14 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40243-016-0078-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40243-016-0078-9