Abstract

Microencapsulating a phase-change material (PCM) has become a prominent method of creating a stable environment in which the PCM can undergo its phase change without affecting the environment in which it is used. The method of encapsulation used in this study takes advantage of a new technology known as membrane emulsification and suspension polymerization. This study investigates the encapsulation of the paraffin wax RT21® in a poly(methyl methacrylate) shell, which could be used to increase the thermal mass of a building. The objectives of the study are: (1) to encapsulate RT21® through the use of membrane emulsification and (2) to test the mechanical properties of the microcapsules under nanocompression. Membrane emulsification was carried out using Shirasu porous glass hydrophilic membranes of pore sizes 10, 10.2, and 20 μm. Polymerization was conducted in a batch reactor with methyl methacrylate as the monomer in the temperature range 70–90 °C. The thermal properties (the latent heat of melting and melting temperature) of the microcapsules were tested using a differential scanning calorimeter. Particle size analysis was conducted to determine the average size distribution of the microcapsules produced. Membranes with pore sizes of 10, 10.2, and 20 μm produced microcapsules with average diameters of 22.40 ± 1.47, 25.38 ± 0.80, and 37.50 ± 1.69 μm, and average latent heats of 113.91 ± 12, 116.69 ± 1.40, and 109.89 ± 8.69 J/g, respectively. In order to determine the mechanical properties of these microcapsules, a modified nanoindentation compression technique was used to test the bursting force for individual microcapsules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Increasing the thermal inertia of buildings through the use of phase-change materials (PCMs) can be an effective method of reducing energy consumption [1–3]. An extensive review of PCMs can be found in [1, 4, 5].

The PCM RT21® has a melting temperature range of 20–22 °C, which is close to the human comfort temperature [6]. Due to the nature of PCMs, the bulk usage of PCM in buildings can become problematic. Microencapsulated PCMs can be advantageous for the thermal insulation of buildings [7].

The microencapsulation of PCMs (MPCM) is a technique that has received considerable attention recently. Microcapsules comprise of an internal core material and an external encapsulating shell material. MPCM allows the core material to undergo phase (and volume) changes without affecting the bulk structure or integrity of a building [7]. Comprehensive reviews of the microencapsulation of PCMs can be found in Tyagi et al. [7] and Zhao et al. [8].

There are two major ways in which microcapsule shells can be formed: via an out-inside process or an inside-out process. Examples of each method are provided in [9] and [10].

Membrane emulsification can be used as an alternative to traditional emulsification to create microcapsules. While traditional methods of emulsification via mechanical means are sometimes faster than membrane emulsification, a broad range of particle sizes are produced. Furthermore, as mentioned by Charcosset et al., the process of membrane emulsification utilizes less energy than traditional mechanical methods. The principle of membrane emulsification, much like traditional emulsification, is that a dispersed phase is created in a continuous phase. A key characteristic of membrane emulsification is that the droplet size is controlled primarily by the size of the pores of the membrane itself. This allows specific size droplets to be generated [11, 12]. Membrane emulsification was used in this study to create a colloidal mixture using Shirasu porous glass membranes (SPG) developed by Nakashima et al. [13].

Previous work by Omi et al. [14] proposed the production of poly(methyl methacrylate) microcapsules (PMMA) through the use of SPG membrane emulsification.

Elucidating the mechanical properties of microcapsules provides crucial information about the extent to which microcapsules can be implemented for different applications. MPCM are commonly mixed with with building materials, and are vulnerable to rupture during mixing or compaction. One requirement of the microcapsules is to maintain structural integrity in order to prevent the PCM from leaking out, which would drastically affect the efficiency of the PCM and lead to potential interactions of the PCM with other materials in the surrounding environment [1].

While some initial studies have been performed to determine the mechanical properties of microcapsules [15–17] and other materials of a similar size [18], a standard method of testing microcapsules is yet to be fully developed, although Rahman et al. [19] proposed a new standard method of measuring the mechanical properties of individual commercially available Micronal® DS5008 microcapsules.

The aim of this study was to encapsulate RT21® (core) in poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA, shell) by suspension polymerization, using hydrophilic SPG membranes with pore sizes of 10, 10.2, and 20 μm in the emulsification step. While membrane emulsification has been used in prior studies, to the author’s knowledge, the encapsulation of RT21® in a PMMA shell via membrane emulsification has not been mentioned elsewhere. This study also builds upon studies of the rupture of individual microcapsules using a nanomechanical setup. It is surprising that even commercially produced PCM microcapsules have not been widely tested for mechanical strength. An additional study of the mass loss of microcapsules under heating is also discussed in this paper.

Materials and methods

Two separate solutions were prepared: the aqueous phase and the organic phase. Emulsification was carried out first, followed by polymerization, washing steps, and drying. The chemicals used in this study (unless otherwise stated) were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Aqueous phase

Polyvinylalcohol (PVA; 5.70 g) and sodium nitrite (polymerization inhibitor; 0.21 g) were dissolved in 150 ml of distilled water.

Organic phase

The organic phase consisted of 7.20 g methyl methacrylate (MMA), 2.87 g ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EDMA, crosslinker), 0.19 g benzoyl peroxide (BPO, initiator), and 24.95 g of RT21® (PCM, Rubitherm GmbH, Berlin, Germany). BPO was dissolved in EDMA first, and then MMA was added, followed by the RT21®.

Emulsification

The SPG hydrophilic membranes are tubular, with the continuous phase passing through the interior of the tube and the dispersed phase entering the interior of the tube through the membrane pores from the shell side. This study used membranes with pore sizes of 10, 10.2, and 20 μm (part numbers: SPG: PJN03D25, PJN08C03, and PJN03K20, respectively), which were pre-soaked in the aqueous phase (continuous phase) for 10 min prior to emulsification [12].

Due to the complex nature of the membrane emulsification step, a diagram that better explains the process is provided (see Fig. 1). The organic phase (dispersed phase) was loaded into vessel D and sealed. A 500 ml beaker under the outlet from the membrane section contained the aqueous phase. Dispersion of the organic phase through the pores of the membrane and into the aqueous phase allowed the formation of an emulsion. Vessel B was subjected to 10 kPa of N2 to ensure the organic phase was completely dispersed in the aqueous phase.

Schematic of a SPG Technology (Miyazaki, Japan) fast mini-kit (adapted from the SPG Technology manual). 1 Needle valve, 2 vessel vent valve, 3 pressure valve, 4 module vent valve, 5 valve controlling flow into SPG module, 6 valve controlling flow exiting SPG module, A digital pressure gauge, B pressure vessel, C vessel vent, D SPG module, E pump, F beaker, G module vent

Polymerization

The emulsification product was transferred to a 400 ml glass reactor (6.5 cm diameter, 12.05 cm height) in a pre-warmed water bath (80 °C initial temperature), and agitation was set to 240 rpm. The temperature of the water bath was maintained at 80 °C for 2 h, increased to 90 °C for 4 h, and then set to ambient room temperature. The process that was used to produce PMMA is known as free radical vinyl polymerization. This method utilizes BPO as the radical initiator and MMA as the monomer. The advantage of BPO is that it is a relatively nonpolar molecule and thus dissolves easily when mixed with other nonpolar molecules such as paraffin waxes.

Extraction of microcapsules

After polymerization, the microcapsules were washed three times with deionized water to remove impurities. The purified microcapsules were dried at room temperature for 24 h.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

DSC (DSC-60, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used to determine the melting range and latent heat of the microcapsules. DSC was carried out within the temperature range of −20 to 60 °C at a heating rate of 3 °C/min or less. At 60 °C, the temperature was held constant for 10 min. Air was used to purge the system at 100 ml/min and liquid nitrogen was used as the refrigerant. Calibration of the DSC was conducted with n-octadecane (GC grade 99 %, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Each 4–6 mg sample of microcapsules was weighed in an aluminum DSC pan. An aluminum reference pan was used in the DSC. Each sample of microcapsules was examined twice, and the resulting melting temperatures and latent heats were averaged. The latent heat was calculated from a plot of power versus temperature (°C), and integration was carried out using the DSC software package. The amount of RT21® encapsulated was calculated using:

where ΔHmicrocapsule is the latent heat of the microcapsule and ΔHpure paraffin is the latent heat of pure paraffin wax [10].

Particle size analysis (PSA)

A particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 2000, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) was used to determine the sizes of the microcapsules. The microcapsules were dispersed in distilled water, and the refractive index of MMA was used (1.412 at 25 °C) [20].

Mass loss

To simulate real-life applications of MPCM in buildings, a simple mass loss analysis was conducted. Samples of microcapsules (0.5 g each sample) were weighed out and spread into labeled aluminum pans (53.5 mm in diameter). Each pan was fully covered with microcapsules to give a constant surface area. The pans were loaded onto a tray in a drying oven pre-set to 50 °C. Every 24 h, for a period of one week, the samples were removed from the drying oven and weighed.

Nanoindentation

Nanoindentation of individual microcapsules was carried out as described in Rahman et al. [19]. The microcapsules were fixed onto the surface of an epoxy substrate and indentation testing was carried out using an MTS nanoindenter system (MTS, TN, USA) equipped with a 10 μm, 60° conospherical diamond tip, as well as an optical microscope with a 40× objective.

Results and discussion

Microencapsulation experiments were carried out in triplicate. The results for the microcapsules generated using 10 and 20 μm pore membranes are discussed in detail below as examples of the analysis conducted (see the section “Microencapsulation experiments involving 10 and 20 µm pore size membranes” below), although the section “Summary of the microencapsulation experiments performed using 10, 10.2, and 20 µm pore size membranes” summarizes the results for all of the samples carried out in this study. The “Nanoindentation” section discusses the use of nanocompression.

Pure RT21®

Prior to the encapsulation of RT21®, the properties of a pure sample of RT21® were verified in duplicate. Approximately 5–10 mg of RT21® were used in each DSC run. A sample of the DSC curve generated by the software is shown in Fig. 2. Integration was also performed using the DSC software package, which gave an average latent heat value of 132.75 J/g, as compared to the value of 134 J/g reported by the manufacturer, and an average peak melting temperature of 23.12 °C. The average temperature corresponding to the onset of melting in the two runs was 17.09 °C, and the average endset temperature was 27.26 °C.

Microencapsulation experiments involving 10 and 20 μm pore size membranes

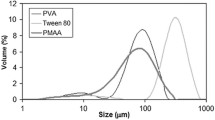

Microscopic images of the two samples are shown in Fig. 3. The microscopic images show that the microcapsules produced using the 10 μm membrane are smaller than those produced with the 20 μm membrane. This is confirmed by particle size analysis (Fig. 4): microcapsules produced with the 10 μm membrane had an average diameter of 25.65 μm, while microcapsules produced with the 20 μm membrane had an average diameter of 43.52 μm. Comparing the size distributions for the two curves in Fig. 3, the volume percentages of the samples are seen to be quite similar (approximately 9.5 and 9.0 % at their respective average microcapsule diameters). This is an indication that membranes with different pore sizes produce microcapsules with similar size distributions when the membrane emulsification method is used.

Sample particle size distributions for microcapsules produced using SPG membranes with 10 and 20 μm pores, respectively. The average diameters of the microcapsules produced using the 10 and 20 μm pore size membranes were 25.65 and 43.52 μm, respectively. The volume percentages were 9.0 and 9.5 % at these average diameters. Solid and dashed lines indicate 10 and 20 μm pore size membranes, respectively

It is important to have a narrow size distribution, and also important that the thermal properties of the microcapsules produced are acceptable for use in buildings. The DSC thermographs of microcapsules produced using the 10 and 20 μm pore size membranes showed peak melting temperatures of 21.24 and 21.16 °C, and their latent heats of melting were 112.27 and 117.19 J/g, respectively (Figs. 5, 6). These latent heat values indicate that the thermal properties of the microcapsules are appropriate for use in buildings.

Figure 7 shows the mass loss from microcapsules over a period of one week when placed in an oven at 50 °C. Microcapsules produced using the 10 and 20 μm pore size membranes lost 0.71 and 4.2 % of their initial masses, respectively. The larger microcapsules lost more mass than the smaller microcapsules over the same time period. This is due to the fact that, even though both sets of microcapsules had the same temperature profile for polymerization, the larger droplets of organic phase material had less polymer deposited on the surface of the droplet and thus did not form a sufficiently thick shell. This is also apparent from the DSC result, as microcapsules produced from the 20 μm pore size membrane had a higher latent heat of melting than microcapsules produced from the 10 μm pore size membrane. Using Eq. 1, the microcapsules produced using the 10 and 20 μm pore size membranes were calculated to have core:shell ratio of 0.84:0.16 and 0.88:0.12, respectively.

Summary of the microencapsulation experiments performed using the 10, 10.2, and 20 μm pore size membranes

The previous section described an example of the successful encapsulation of RT21® using membrane emulsification with 10 and 20 μm pore size hydrophilic membranes. To demonstrate the results reported in that section were reproducible, triplicate studies were carried out on microcapsules produced using the 10, 10.2, and 20 μm pore size hydrophilic membranes. These results are summarized in Table 1.

According to the results presented in Table 1, the thermal properties of RT21® are conserved upon microencapsulation in membranes with different pore sizes. The average peak melting temperatures of the RT21® encapsulated in 10, 10.2, and 20 μm pore size membranes were 20.73 ± 0.13, 21.10 ± 0.14, and 20.72 ± 0.20 °C, respectively, which are close to that seen for unencapsulated RT21®. The lower melting temperatures of the microencapsulated RT21® samples can be attributed to the presence of impurities in the final product.

The latent heats of melting for the microcapsules produced using the 10, 10.2, and 20 μm pore size membranes were 113.91 ± 12.0, 116.69 ± 1.40, and 109.89 ± 8.69 J/g, respectively. These high values for the latent heat of each sample demonstrate that microcapsules can be produced using this method without any significant loss of the thermal properties of the PCM RT21®.

The level of encapsulation of the PCM RT21® was above 82 % for all of the samples prepared using the 10, 10.2, and 20 μm membranes. This is significant, as it means that the majority of the PCM is encapsulated, showing that the polymerization and crosslinking are successful. Regardless of the size of the microcapsules created, at least 82 % of the PCM RT21® will be encapsulated. Minimizing the percentage of PCM lost during the encapsulation processes will be vital when scaling up this process.

The diameters of the microcapsules produced using the 10, 10.2, and 20 μm pore size membranes were 22.40 ± 1.47, 25.38 ± 0.80, and 37.50 ± 1.69 μm, respectively. The size of the microcapsules produced was linearly dependent on the pore size of the membrane used during emulsification—the larger the pore size, the larger the microcapsules produced. This is advantageous, as different microcapsule sizes may be required for different MPCM applications.

In addition, this study demonstrates that membrane emulsification using SPG membranes can be used not only for Thermal energy storage in PCMs but also for other applications requiring microencapsulation.

Nanoindentation

In order to validate this test method, initial nanocompression tests were conducted on commercially available samples (Microtek MPCM-18D and Microtek MPCM-24D; Microtek Laboratories, Inc., Dayton, OH, USA), and then on the microcapsules created in this study.

The average size of the tested microcapsules from MPCM-18D was measured optically as 24.64 μm. Care was taken to select microcapsules with diameters close to 20 μm, as it was assumed that they would have similar shapes and sizes, facilitating comparisons between the tests.

Microscopic images were taken before and after the nanocompression of a microcapsule (Fig. 8). The images showed that the microcapsule ruptured during testing. The microcapsule shown in the images had an initial diameter of 18.75 μm, and the ruptured shell diameter was measured as 28.11 μm. In addition to optical images, load–displacement curves from the compression test were used to calculate the force required to rupture the microcapsule. To ensure that the whole microcapsule had been compressed, a force larger than that required to collapse the microcapsule was used, producing a loading curve with two slopes. The initial slope corresponded to microcapsule compression. The second slope corresponded to indentation of the underlying substrate. The point at which the initial slope changed into the second slope is indicated by an arrow labeled “A” in Fig. 9. Indentation tests were carried out on blank substrate samples as a reference, and these loading curves were used to confirm that the microcapsule had been fully compressed and the substrate was being indented (when the secondary loading slope is the same as the substrate loading slope, it can be assumed that the secondary slope is due to substrate indentation, as shown in the upper left plot of Fig. 9).

Force versus displacement curve for the nanoindentation of MPCM-18D run 20 and blank substrate samples. Point A indicates the microcapsule rupture point at a displacement (D) of 2,503 nm and a force (F) of 0.67 mN. The upper left curve is an enhanced view of the regions of graph between 0 and 6,000 nm, demonstrating that both the blank and microcapsule curves have similar slopes

The microcapsules made in this study using RT21® as the core material and MMA shells were dried in the laboratory. However, some samples agglomerated, which made it difficult to test individual microcapsules. Therefore, we decided only to test samples that did not have agglomerated microcapsules (sample numbers 17, 18, 20, and 28) to ensure that the test protocols were being followed precisely.

Table 2 displays the results from nanocompressing all of the microcapsule samples tested in this study, where each run number corresponds to a different microcapsule in the same sample set. According to these preliminary experiments, the microcapsules produced in this study via membrane emulsification are comparable to commercially available microcapsules (MPCM-18D and MPCM24D).

Conclusions

This study demonstrated a new process for microencapsulating a paraffin wax, RT21®, with poly(methyl methacrylate) via membrane emulsification and suspension polymerization. Membrane emulsification was carried out with hydrophilic SPG membranes with pore sizes of 10, 10.2, and 20 μm, producing microcapsules with average diameters of 22.40 ± 1.47, 25.38 ± 0.80, and 37.50 ± 1.69 μm and average latent heats of 113.91 ± 12, 116.69 ± 1.40, and 109.89 ± 8.69 J/g, respectively. The thermal characteristics of the microcapsules produced in this study indicate that they can be used to increase the thermal capacity of buildings.

Nanocompression of microcapsules produced in this study, in addition to commercially available microcapsules, was also conducted. Based on the preliminary results, it is clear that there is a further need to investigate the nanocompression of individual microcapsules and to develop a correlation between microcapsule size and the force required for rupture.

References

Khudhair, A.M., Farid, M.M.: A review on energy conservation in building applications with thermal storage by latent heat using phase change materials. Energy Convers. Manag. 45, 263–275 (2004)

Cabeza, L.F., Castell, A., Barreneche, C., De Gracia, A., Fernández, A.I.: Materials used as PCM in thermal energy storage in buildings: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15, 1675–1695 (2011)

Zhou, D., Zhao, C.Y., Tian, Y.: Review on thermal energy storage with phase change materials (PCMs) in building applications. Appl. Energy 92, 593–605 (2012)

Zalba, B., Maran, J.M., Cabeza, L.F., Mehling, H.: Review on thermal energy storage with phase change: materials, heat transfer analysis and applications. Appl. Thermal Eng. 23, 251–283 (2003)

Farid, M.M., Khudhair, A.M., Razack, S.A.K., Al-Hallaj, S.: A review on phase change energy storage: materials and applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 45, 1597–1615 (2004)

Behzadi, S., Farid, M.M.: Experimental and numerical investigations on the effect of using phase change materials for energy conservation in residential buildings. HVAC R Res. 17, 366–376 (2011)

Tyagi, V.V., Kaushik, S.C., Tyagi, S.K., Akiyama, T.: Development of phase change materials based microencapsulated technology for buildings: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15, 1373–1391 (2011)

Zhao, C.Y., Zhang, G.H.: Review on microencapsulated phase change materials (MEPCMs): fabrication, characterization and applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15, 3813–3832 (2011)

Bayés-García, L., Ventolà, L., Cordobilla, R., Benages, R., Calvet, T., Cuevas-Diarte, M.A.: Phase change materials (PCM) microcapsules with different shell compositions: preparation, characterization and thermal stability. Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells 94, 1235–1240 (2010)

Sánchez-Silva, L., Rodríguez, J.F., Romero, A., Borreguero, A.M., Carmona, M., Sánchez, P.: Microencapsulation of PCMs with a styrene-methyl methacrylate copolymer shell by suspension-like polymerisation. Chem. Eng. J. 157, 216–222 (2010)

Charcosset, C., Limayem, I., Fessi, H.: The membrane emulsification process—a review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 79, 209–218 (2004)

Joscelyne, S.M., Trägårdh, G.: Membrane emulsification—a literature review. J. Membr. Sci. 169, 107–117 (2000)

Nakashima, T., Shimizu, M., Kukizaki, M.: Membrane emulsification by microporous glass. Key Eng. Mater. 61–62, 513–516 (1991)

Omi, S., Katami, K., Taguchi, T., Kaneko, K., Iso, M.: Synthesis of uniform PMMA microspheres employing modified SPG (Shirasu porous glass) emulsification technique. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 57, 1013–1024 (1995)

Sun, G., Zhang, Z.: Mechanical strength of microcapsules made of different wall materials. Int. J. Pharm. 242, 307–311 (2002)

Zhang, Z., Sun, G.: Mechanical properties of melamine-formaldehyde microcapsules. J. Microencapsul. 18, 593–602 (2001)

Su, J., Ren, L., Wang, L.: Preparation and mechanical properties of thermal energy storage microcapsules. Colloid Polym. Sci. 284, 224–228 (2005)

Arfsten, J., Bradtmoller, C., Kampen, I., Kwade, A.: Compressive testing of single yeast cells in liquid environment using a nanoindentation system. J. Mater. Res. 23, 3153–3160 (2008)

Rahman, A., Dickinson, M., Farid, M.: Microindentation of microencapsulated phase change materials. Adv. Mater. Res. 275, 85–88 (2011)

Yaws, C.L. (ed.): Yaws’ handbook of thermodynamic and physical properties of chemical compounds. Knovel, Beaumont; 2003

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Rahman, A., Dickinson, M.E. & Farid, M.M. Microencapsulation of a PCM through membrane emulsification and nanocompression-based determination of microcapsule strength. Mater Renew Sustain Energy 1, 4 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40243-012-0004-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40243-012-0004-8