Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to present the course of a thermal cycle induced by welding in characteristic points in a joint and demonstrate the capabilities of simulation techniques with regard to thermal analysis of welding. Hybrid plasma-arc welding (HPAW) tests were conducted on samples of advanced high-strength steel (AHSS). Welding FEM analysis was carried out. Cooling time was determined for characteristic zones in the joint. The results of the simulation were then juxtaposed with the experimental data. Considerable diversification of the t8/5 and t8/3 times was observed for the analysed areas in the joint. The description of the thermal cycle presented in this paper questions the validity of analysing the changes occurring in the HAZ with the use of conventional TTT diagrams, extending the analysis of thermal conditions of a produced joint by new techniques of numerical prediction of thermal history of HPAW.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Numerical simulations provide information on physical phenomena which can be obtained in an experiment limited to the revision of calculations. This was confirmed by Stix et al. [1] who used in their research a specialist dedicated software—simufact.welding. Such applications have built-in functions responsible for defining heat sources, trajectories, fastening devices, multi-phase materials, etc. Methods of precise representation of different heat sources are still being researched. Wu et al. [2] proposed a new improved numerical model of a plasma heat source that encompassed the specificity of energy transfer within a stream of plasma gas.

Simulations in welding take into consideration every aspect of production of joints, along with their properties. It is possible to conduct an analysis of metal and heat dispersion in the weld pool during GMAW, which was done by Cheon et al. [3], or during HPAW (for heat sources aligned centrically along a single axis), which was done by Liu et al. [4]. Simulations of hybrid welding process focus mainly on the GMAW processes as well as the ones in which laser is used (hybrid laser-arc or arc-laser welding, depending on the order of heat sources). One example of such an experiment is the analysis of stresses and strains which was conducted by Zhan et al. [5], who were investigating the use of HALW process in terms of welding the Ni-Fe (invar36) alloy.

Simulations of the strength of welded joints that take into consideration the changes in the HAZ strength resulting from annealing and tempering are also conducted. Maurer, Panda, and Mochizuki et al. [6,7,8] performed quasi-static simulations of a HAZ with a diversified microstructure, which allowed them to determine the influence of a relative thickness of the tempered zone on the properties of the joints.

On the basis of a simulation, Goldak et al. [9] showed that when the amount of supplied heat is constant, one can find a correlation between welding speed and the thermal effect that can be observed in the HAZ.

Simulations can also be a source of data that can be used for training artificial neural networks. Yu and Krajewski et al. [10, 11] created such a network that was later used for the prediction of hardness on the basis of technological parameters.

The number of works dedicated to HPAW process simulations is scarce. So far, this issue has been taken up by Nowacki et al. [12] who made an attempt to determine thermal cycle conditions. There is a need to extend the knowledge concerning simulations of hybrid welding that makes use of a complex heat source, i.e. one that includes a plasma source and a classical one.

The subject area of high-efficiency welding of advanced high-strength steels is one of the mainstream issues in contemporary welding. It encompasses questions related to the weldability of advanced high-strength steel (AHSS) and the possibilities for employing innovative welding technologies in the process of joining thereof.

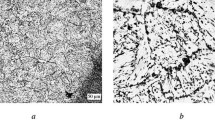

Specific processability and performance of such materials can be obtained by proper doping and complex heat and thermo-mechanical treatment (Fig. 1) [13].

AHSS can also include second-generation steels that are characterised not only by their high strength but also by their very high plasticity. The steels encompass duplex type ferritic-austenitic steels with the addition of manganese as an ingredient that stabilises austenite as well as steels with the TWIN and TRIP effects. The third-generation AHSSs that are currently being developed are characterised by a more advantageous strength-plasticity ratio than the first-generation steels and by a lower price than the second-generation AHSS [14,15,16,17,18].

AHSSs are used when the mass-loading capacity ratio is of high importance for the attractiveness of a construction. Welding is considered a natural method of joining in this area; however, the negative influence of supplied heat on the properties of steel prone to annealing constitutes a major disadvantage [19,20,21]. The parameter that characterises the amount of heat supplied into the joint is the cooling time in the temperature range between 800 and 500 °C, marked as t8/5. In the case of advanced high-strength steels, the span of t8/5 values becomes significantly limited, edging towards low values. The structure of AHSS—shaped in the complex process of thermo-mechanical treatment—should remain as unspoilt by the welding heat as possible (Fig. 2) [22,23,24,25,26,27].

Construction steels and recommended values of t8/5 cooling time. Classical steels: interstitial free, if high strength, mild steels, bake hardenable, high-strength low-alloy/ferritic-bainitic. Stale AHSS: dual phase, transformation-induced plasticity, complex phase, twinning induced plasticity MnB + HF (doped with manganese and boron, hardened - hot forming), martensitic (MART)

Such a situation triggers the development of welding techniques, and it consists in decreasing the amount of supplied heat while keeping the weld metal fusion coefficient at a high level. In recent years, a lot of processes that maximise electrode fusion have emerged. In effect, high welding speeds can be obtained, which results in the production of more favourable properties of the joints. Another step on the way to improve the thermal balance is combining different welding processes within a single head. A combination of a high-energy laser or plasma heat source with a source that would ensure efficient filling of the weld groove in the GMAW process seems to be the only way to fulfil the increasingly strict requirements. In hybrid processes, it is possible to obtain extremely high welding speeds while at the same time reducing the number of runs to a single one, even when the thickness of a material exceeds 10 mm [28, 29]

2 Prediction of cooling time of a welded joint

The analysis of the capabilities of simulation methods in terms of prediction of cooling time of a HPAW joint was based on seven experiments that involved welding model joints and making an attempt at modelling the whole process.

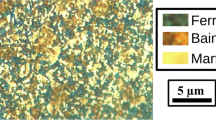

Model butt joints were made from S960QL and S1300QL steels (Table 1) and bevelled so as to produce a single 20° V groove. Nonlinear thermal characteristics of materials based on temperature and multi-phase composition were applied (Fig. 3).

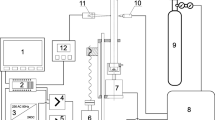

The joints were made at the robotized hybrid welding system shown in Fig. 4.

Schemes of the robotic welding station (a) and HPAW hybrid welding head (b) used in research. 1: HPAW welding head; 2: robotized manipulator; 3: plasma and shielding gas cylinders; 4: manipulator power source and control panel; 5: plasma power source; 6: welding table; 7: GMAW power source; 8: arcs positioning system (constant magnetic field generator); 9: plasma torch; 10: GMAW torch

In order to determine the thermal conditions necessary to ensure appropriate fusion, low range of welding parameters was employed, so that minimal amount of supplied heat was generated. The values of thermal heating T0 and welding speed vw and the amount of supplied heat Qc are shown in the table below (Table 2).

The simulation was conducted on the basis of the geometry obtained from microsections of welded joints. Temperature analysis was done within the area of cross-section divided into a mesh of reference points (Fig. 5).

The heat sources were defined as a well-known heat source models. First (used for GMAW process), double-ellipsoidal shaped Goldak’s and second, used for Plasma—two connected Pavelic’s disc shaped models [30] (Fig. 6).

For each sample series, a different heat source geometry was used; it corresponded to the thermal power of the arc and the geometry of the pool (Table 3). The parameters described in Table 3 have been selected experimentally. Their values reflect the thermal effect visible on cross-sections of welded joints.

3 Results

The simulations were carried out in accordance with the plan presented in the paper, taking into consideration the phenomenon of weld overlap (Fig. 7).

The result of the numerical simulation of welding the B9-180 sample. Isometric view of the welded fragment of the joint (a) and section view (b) showing the pool of molten metal and executed function “mesh refinement” increasing mesh density around the moving heat source (min. element size, 0.25 mm)

Fusion zone was represented as a diagram of maximum temperature value on the cross-section, located midway along the length of the joint. In this case, the white area representing the temperature that exceeds melting point marks the boundary of the weld (Fig. 8).

The simulation method made is possible to characterise thermal history in any given point in the joint. After delineating the fusion line for each sample, temperature changes in the HAZ were investigated. A point located 2 mm from fusion line and 3 mm beneath the surface of the plate was adopted as a representative spot (Fig. 9).

It is possible to determine the t8/5 time in the point analysed in Fig. 9 only for the B18-30 sample that was welded with twice as high heat input than the previous one. In order to make it possible to compare the processes, the t6/3 times were determined as well.

Depending on the amount of heat supplied, the maximum temperatures (660 – 1040 °C) change and so does the cooling dynamics in the temperature range of 600 – 300 °C (10 – 24.5 s). Consequently, the HAZ becomes narrower and moves towards the fusion line.

Figure 9 shows slight disparities between the A (S960QL) and B (S1300QL) samples resulting from their having different thicknesses, material properties, and interpolations made between the mesh nodes where the analysed point was located.

The thermal history of the following characteristic points in the joints was analysed:

-

FZ – point no. 1 located on the axis of the joint (fusion zone) above 1510 °C;

-

FL – fusion line of the temperature of 1510 °C;

-

SZ – annealed soft zone in the temperature range of 600 – 700 °C;

-

PM – an area of partly decrystallised parent material, located right outside the HAZ below 500 °C.

The points were selected considering the shifting maximum temperature fields (Fig. 10) that moved due to varying amount of supplied heat. Since only minor differences were observed in the cooling dynamics of the A and B samples (Fig. 9), it were the S1300QL (B) samples that underwent further analyses.

The determinable t8/5 time comprises the weld as well as a narrow adjacent zone. Figure 9 shows that in order to register a temperature exceeding 800 °C at a distance of 2 mm from the fusion line, it is necessary to supply a considerable amount of heat into the joint. In our case, it was possible when welding parameters generated the amount of heat that exceeded 9 kJ/cm. Obtaining such temperature in the soft zone seems difficult to achieve.

A temperature that is easier to obtain in the whole HAZ is the temperature of 600 °C. It is high enough to trigger the tempering of martensite which is the main structural ingredient in AHSS of MART type. In order to quantify cooling dynamics in the HAZ in martensitic steels, it is more accurate to consider cooling time in a lower range of temperatures, i.e. up to 300 °C which is the borderline temperature for low-temperature tempering that the steel underwent in the manufacturing process. The t6/3 time is more adequate for other AHSS presented in this paper, whose martensitic structure is prone to annealing (Fig. 1).

Obtaining a thorough joint penetration for the HPAW process when the t8/5 time is lower than 10 s (as it is recommended) proves impossible. It is only possible to obtain such a value in case of multi-pass GMAW. This process, however, is not recommended due to the destructive influence the complex thermal cycle has on the strength of a joint. It is important to determine welding parameters that guarantee obtaining an appropriate joint without supplying too much heat in a very precise way. The problem can be solved by computer simulations. Further research on hybrid heat source is needed in order to fully reproduce the actual welding conditions.

4 Summary

Having analysed the results of the experiments, the following conclusions were drawn:

-

(1)

Simulation methods allow to characterise the thermal cycle in any given point in the weld, with the use of any given geometry of the welded joint and a wide range of more or less complex heat sources. Therefore, it is possible to examine the complete thermal history of the joint area and to interpret the phenomena occurring in its structure correctly.

-

(2)

A parameter characterising the structure of the HAZ in MART steel and its proneness to tempering in a direct way is the t6/3 time. Contrary to the t8/5 time, the t6/3 time can be determined in the whole HAZ and has a more stable cooling dynamics.

-

(3)

The minimum range of welding parameters for the analysed joint geometry was established. The parameters generate slightly different cooling times when entered into the software than the cooling times observed in the experiment. It is due to the fact that it is difficult to estimate the amount of heat supplied solely on the basis of the values of voltage and current parameters registered by the welding devices. In order to determine the values of these parameters in an unambiguous way, it is necessary to establish the thermal characteristics of a hybrid heat source in an experiment, which will be the object of further research.

-

(4)

When appropriate material definitions are employed, i.e. ones including temperature characteristics of a multi-phase structure, it is possible to visualise such properties of a joint as phase composition, hardness, state of stresses, and strains, and to shape them depending on welding parameters. Due to specialist welding FEM software, it is possible to determine optimum parameters in welding advanced construction materials using modern, highly efficient methods.

References

Stix G, Buchmayr B (2015) Investigation of residual stresses and distortions produced in tubular. IIW Int Conf High-Strength Mater - Challenges Appl 1–5

Wu CS, Wang HG, Zhang YM (2006) A new heat source model for keyhole plasma arc welding in FEM analysis of the temperature profile. Weld J 85:284–291

Cheon J, Kiran DV, Na S-J (2016) CFD based visualization of the finger shaped evolution in the gas metal arc welding process. Int J Heat Mass Transf 97:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2016.01.067

Liu ZM, Cui SL, Luo Z, Zhang CZ, Wang ZM, Zhang YC (2016) Plasma arc welding: process variants and its recent developments of sensing, controlling and modeling. J Manuf Process 23:315–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2016.04.004

Zhan X, Li Y, Ou W, Yu F, Chen J, Wei Y (2016) Comparison between hybrid laser-MIG welding and MIG welding for the invar36 alloy. Opt Laser Technol 85:75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2016.06.001

Maurer W, Ernst W, Rauch R et al (2013) Numerical simulation on the effect of HAZ softening on static strength of HSLA steel welds. In: Sommitsch C, Enzinger N (eds) Math. Model. Weld Phenom, vol 10. Verlag der Technischen Universität Graz, Graz, pp 669–690

Panda SK, Kuntz ML, Zhou Y (2009) Finite element analysis of effects of soft zones on formability of laser welded advanced high strength steels. Sci Technol Weld Join 14:52–61. https://doi.org/10.1179/136217108X343920

Mochizuki M, Shintoni T, Hashimoto Y, Toyoda M (2004) Analytical study on deformation and strength in HAZ-softened welded joints of fine-grained steels. Weld world 48:2–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03263396

Goldak J, Asadi M, Alena RG (2010) Why power per unit length of weld does not characterize a weld? Comput Mater Sci 48:390–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2010.01.030

Yu L, Kameyama M, Hirano S, et al (2015) Neural network-based hardness and toughness prediction in HAZ of temper bead welding repair technology. IIW Int Conf High-Strength Mater - Challenges Appl 1–7

Krajewski S, Nowacki J (2014) Dual-phase steels microstructure and properties consideration based on artificial intelligence techniques. Arch Civ Mech Eng 14:278–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acme.2013.10.002

Nowacki J, Sajek A (2016) Numerical simulation of the thermal cycle of the PAW-MAG hybrid welding of advanced high strength steels heat distribution in PAW-MAG. Inst Weld Bull 60:13–19. https://doi.org/10.17729/ebis.2016.6/2

Spindler H, Klein M, Rauch R et al (2012) High strength and ultra high strength hot rolled steel grades – products for advanced applications. BHM Berg- und Hüttenmännische Monatshefte 157:108–112

Sohn SS, Choi K, Kwak J et al (2014) Novel ferrite-austenite duplex lightweight steel with 77% ductility by transformation induced plasticity and twinning induced plasticity mechanisms. Acta Mater 78:181–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2014.06.059

Grajcar A, Kuziak R, Zalecki W (2012) Third generation of AHSS with increased fraction of retained austenite for the automotive industry. Arch Civ Mech Eng 12:334–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acme.2012.06.011

Martis CJ, Putatunda SK, Boileau J (2013) Processing of a new high strength high toughness steel with duplex microstructure (ferrite+austenite). Mater Des 46:168–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2012.10.017

Aydin H, Essadiqi E, Jung I-H, Yue S (2013) Development of 3rd generation AHSS with medium Mn content alloying compositions. Mater Sci Eng A 564:501–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2012.11.113

Herrera C, Ponge D, Raabe D (2011) Design of a novel Mn-based 1 GPa duplex stainless TRIP steel with 60% ductility by a reduction of austenite stability. Acta Mater 59:4653–4664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2011.04.011

Keeler S, Kimchi M (2014) Advanced high strength steels for automotive industry. WorldAutoSteel 5:200–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1644-9665(12)60197-6

Fiedler M, Rauch R, Schnitzer R, et al (2015) The alform® welding system. The world’s first system for high-strength welded structures. IIW Int Conf High-Strength Mater - Challenges Appl 1–5

Porter DA (2015) Weldable high-strength steels: challenges and engineering applications. IIW Int Conf High-Strength Mater - Challenges Appl:1–13

Schneider C, Ernst W, Schnitzer R et al (2016) Influence of different welding processes on the mechanical properties of structural steel S960MC. Thermec Graz 1

Banerjee K (2016) Improving weldability of an advanced high strength steel by design of base metal microstructure. J Mater Process Technol 229:596–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2015.09.026

Matlock DK, Speer JG (2008) Third generation of AHSS: microstructure design concepts. In: Haldar A, Suwas S, Bhattacharjee D (eds) Int. Conf. Microstruct. Texture Steels Other Mater. Springer, Jamshedpur, India, pp 187–205

Billur E, Cetin B, Gurleyik M (2016) New generation advanced high strength steels: developments , trends and constraints. Int J Sci Technol Res 2:50–62

Fydrych D, Łabanowski J, Rogalski G (2013) Weldability of high strength steels in wet welding conditions. Polish Marit Res 20:67–73. https://doi.org/10.2478/pomr-2013-0018

Certilas Nederland BV (2015) Cooling times (Delta T8/5) S355 till S960 | Certilas. http://www.certilas.nl/en/content/cooling-times-delta-t85-s355-till-s960. Accessed 21 Jun 2015

Yurtisik K, Tirkes S, Dykhno I, Gur CH, Gurbuz R (2013) Characterization of duplex stainless steel weld metals obtained by hybrid plasma-gas metal arc welding. Soldag Inspeção 18:207–216. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-92242013000300003

Fiedler M, Plozer A, Rutzinger B, Scherleitner W (2016) Control of mechanical properties of high strength steels through optimized welding processes. Inst Weld Bull 60:31–37. https://doi.org/10.17729/ebis.2016.5/4

Goldak J, Chakravarti A, Bibby M (1984) A new finite element model for welding heat sources. Metall Trans B 15:299–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02667333

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Recommended for publication by Commission IX - Behaviour of Metals Subjected to Welding

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sajek, A. Application of FEM simulation method in area of the dynamics of cooling AHSS steel with a complex hybrid welding process. Weld World 63, 1065–1073 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-019-00718-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40194-019-00718-z