Abstract

This article aims to present an approach to enhance the firm performance of SMEs by understanding the dynamics between the elements of the transformational leadership style of the CEO and the agility of the supply network. The business environment among SMEs is marked by fierce rivalry, quick change, and tremendous instability. While an agile supply chain is seen as a winning option for manufacturing SMEs, a transformational leadership style of the CEO can be a source of competitive advantage to improve their performance. Thus, an attempt has been made to integrate transformational leadership and supply chain agility elements and delineate their structural relationship using the total interpretive structural modeling method. Results indicate that transformational leaders drive agile initiatives in the supply chain by setting and communicating a vision, encouraging supply chain members to think of innovative solutions for problems, and mentoring them individually to achieve high-performance standards. These practices will make the team members put in extra effort to accomplish the task, thereby establishing a committed and flexible workforce. Conclusions are drawn, and implications are discussed for enhancing firm performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are critical to the economic success of any country. In India, the SME sector has become an essential part of the economy, contributing considerably to job creation, innovation, exports, and inclusive growth (SME Chamber of India, 2020). Furthermore, as manufacturing from industrialized countries is outsourced to these economies, emerging economies such as India are likely to become more dynamic in the future (Govindarajan & Trimble, 2012), making the contexts of SMEs and emerging economies interesting to explore.

On the operational front, SMEs face challenges in efficiently managing the Supply Chain (SC). In India, for example, SMEs do not implement an SC because they perceive it as a customer exertion of power, a fear of losing business with other customers, and a lack of positivism toward the SC philosophy (Thakkar et al., 2012). Further, considering the current dynamic business environment, an agile SC is necessary for SMEs to compete (Braunscheidel & Suresh, 2009). However, an SC can be implemented by having support and commitment from the upper management, strategy creation, development of resources, risk and reward sharing, and the use of technology (Kumar et al., 2015). Therefore, in the case of SMEs, the assumption that organizations are reflections of their top managers may be valid. The upper echelons theory implies that top managers' managerial background and qualities can anticipate strategic decisions and organizational outcomes (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). According to Miller (1983), CEOs in SMEs have more decision-making autonomy than CEOs in large firms because they are less hampered by organizational inertia. The extant literature shows that top management's background, experience, knowledge, and personality attributes can impact a company's performance (Chen et al., 2015; Patiar & Wang, 2016; Ra’ed et al., 2016; Srinivas & Waheed, 2015). Given that leadership is the driving force behind SME activities, it may be worthwhile to examine the impact of the CEO's management style on the performance of a small business.

According to Bass et al. (2003), Transformational Leadership (TL) effectively delivers higher firm performance in today's dynamic and volatile business environment. Scholars in the past have explored the impact of TL and Supply Chain Agility (SCA) on firm performance in different contexts (Alzoubi & Gill, 2022; Chen et al., 2015; Eckstein et al., 2015; Marić & Opazo-Basáez, 2019; Patiar & Wang, 2016; Prabhu & Srivastava, 2022; Ra’ed et al., 2016; Settembre-Blundo et al., 2021; Srinivas & Waheed, 2015; Sundram et al., 2011; Wadhwa & Rao, 2004) separately. Researchers have also modeled the elements of agility for implementing a flexible system (Agarwal et al., 2007; Sharma & Bhat, 2014; Singh et al., 2020). However, there is no unified framework that has integrated the elements of TL and SCA to study ‘how’ they enhance firm performance. This study intends to fill this gap.

The study provides an overview of various elements of TL and SCA and their relative importance in enhancing firm performance. The firm's performance is modeled using the Total Interpretive Structural Modeling (TISM) method to establish a pyramid of enablers. In this study, the elements of TL and SCA are obtained from the literature. These enablers are constructed into dependent and independent variables, and a hierarchical model is thus developed. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 lists and describes TL, SCA, and firm performance elements. The development of the hierarchical TISM model and its validation is explained in Sect. 3. Section 4 deliberates the results. A detailed discussion of the results is presented in Sect. 5. Implications of the findings and Conclusions & Limitations are discussed in Sects. 6, And 7, respectively.

Literature Review

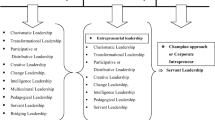

Plenty of literature is available on Supply Chain Management (SCM), leadership styles, and firm performance. Studies have deliberated on the right leadership style needed for improving firm performance and executing the change in the organization, viz., developing collaboration between members or implementing an SC (Wang et al., 2011). In the dynamic business environment, the agility of the SC plays a crucial role in meeting customer requirements and enhancing firm performance. Nonetheless, limited studies show how the CEO's leadership style ensures the implementation of an agile SC, thereby improving firm performance. Many frameworks are available in the extant literature that explains the impact of leadership style and SCA on firm performance, but there has been little attempt to integrate them. While SCA and leadership style are two extreme continuums, one cannot ignore leaders' impact on organizational activities and outcomes (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). Finally, only a few attempts have been made to clarify the structural linkages between the CEO's leadership style and SCA to improve business performance. This section identifies and reflects on leadership style and SCA constructs for attaining superior firm performance.

Constructs of Transformational Leadership Style, Supply Chain Agility and Firm Performance

Competition due to globalization has made businesses improve their internal processes and concentrate on their SC. SCM is defined as controlling an organization's external and internal activities, including procurement, logistics, manufacturing, and distribution, involved in delivering products and services (Chen & Paulraj, 2004; Pagell, 2004; Prajogo et al., 2008). Suppliers play a vital role in building competitive capabilities and delivering value to the final customer. With 70% of manufacturing activities being outsourced (Ates & Bititci, 2011), the SC activities significantly impact the firm performance. There are many aspects of SCM that affect the firm’s performance, like integration, collaboration, and agility (Cao & Zhang, 2011; Eckstein et al., 2015; Huo et al., 2014; Pradabwong et al., 2017; Simatupang & Sridharan, 2008; Sundram et al., 2011; Wiengarten & Longoni, 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). However, considering the current dynamic and turbulent business environment, SCA plays a significant role in meeting customer requirements quickly (Tse et al., 2016).

SCA is the flexibility to absorb short-term changes in the business environment (Lee, 2004). Braunscheidel and Suresh (2009) elucidate SCA as “the capability of the firm, both internally and externally, in conjunction with its key suppliers and customers, to adapt and respond quickly to marketplace changes as well as to potential and actual disruptions.” Li et al. (2008) define an organization’s SCA as the result of integrating the SC’s alertness to changes (opportunities/challenges)-both internal and environmental—with the SC’s capability to use resources in responding (proactively/reactively) to such changes, all in a timely and flexible manner. The above definition of SCA embodies two key components—alertness to changes and response capability. The alertness component highlights agility as an opportunity-seeking capability from internal and external vantage points. In contrast, the response capability component emphasizes agility in change enabling capabilities embedded in organizational processes. Furthermore, Li et al. (2008) characterize SCA into the following dimensions, namely—‘strategic alertness’ (the capacity of the firm to detect changes in its business environment like competitor moves, etc.), ‘strategic response capability’ (The company's ability to incorporate a flexible supply chain to meet the needs of changing market dynamics), ‘operational alertness’ (the firm's ability to notice changes in its current demand and supply sources) and ‘operational response capability’ (ability to respond to changes in demand and supply promptly) (Dove, 2005; Holsapple & Jones, 2005).

Further, extant literature has always posited a positive relation between SCA and firm performance. Scholars widely acknowledge that practices like integrating members of the SC, sharing real-time information, good relations with suppliers and customers, and cellular manufacturing would increase visibility, thereby making the SC agile (Dubey et al., 2018; Eckstein et al., 2015; Tse et al., 2016; Um, 2017). In addition, they highlighted that top management support and commitment are extremely necessary for these activities. The agility thus developed would help firms absorb market fluctuations, enhancing their performance. Hence, it can be noted that to survive in today’s dynamic business environment, firms need to be agile not only internally but also along the SC. In addition, top management teams and transformational leaders play an important role in inducing agility in operations (Mesu et al., 2013; Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010).

Top management leadership is crucial for the success of any organizational activity. As they are idiosyncratic, it is not easy to imitate, and they often create a competitive advantage for the firms. Hambrick and Mason (1984) postulated in their upper-echelon theory that strategic choices and organizational outcomes could be predicted by managerial background and characteristics as organizations reflect their top managers. It is empirically recorded that features like age, tenure, educational background, flexibility, and locus of control of top management teams have a significant influence on the innovativeness and performance of the firm (Bantel & Jackson, 1989; Finkelstein & Hambrick, 1990; Miller & Toulouse, 1986). Further, Miller (1983) suggested that managerial effects are more intense in smaller firms as they are less constrained by organizational inertia. Weiner and Mahoney (1981) view leaders/chief executives as decision-makers who consciously choose among diverse courses of action and determine the fates of their organization.

Johns and Moser (2001) define leadership as an act of influence, a process, and a person’s trait qualities. Scholars have proposed many leadership theories, namely autocratic leadership, democratic leadership, laissez-faire, transformational and transactional leadership. However, Bass et al. (2003) suggest that TL is more effective in achieving higher firm performance considering the current dynamic and turbulent business environment. Transformational leaders motivate their subordinates to go beyond their regular course of work by nurturing a climate of trust and persuading them to prioritize organizational objectives over self-interest (Bass, 1985). Transformational leaders are competent in visualizing success and inspire subordinates to attain their objectives (Keller, 2006). They demonstrate faith in their subordinates' abilities to achieve goals and encourage subordinate coordination and cooperation to obtain superior results (Wang et al., 2011). Bass and Avolio (1994) have identified the following characteristics of transformational leaders: "inspirational motivation" (e.g., aiming to increase awareness and enthusiasm for their goal), "intellectual stimulation" (e.g., inspiring followers to think outside the box), and "individual consideration" (e.g., treating each person differently and helping them to develop their potential).

Furthermore, scholars have explored the influence transformational leaders have on their subordinates in various contexts like hotels, military research and development organization, manufacturing and service organizations and concluded that TL always leads to positive firm performance (Chen et al., 2015; Patiar & Wang, 2016; Raed et al., 2016; Srinivas & Waheed, 2015). They argued that transformational leaders increase firm performance by improving subordinate relations and enhancing individuals' psychological attachment to the team. These evidences help us conclude that leaders play an essential role in all organizational activities, and TL is best suited to enhance firm performance.

Firm performance is the process of quantifying the efficiency and effectiveness of the firm (Neely et al., 1995). Effectiveness is the extent to which a customer’s requirements are met, while efficiency measures how economically a firm’s resources are utilized to meet the customer’s needs. Performance evaluation, according to Kaplan and Norton (1995), is multi-faceted and includes both monetary and non-monetary metrics. A manager’s ability to generate good revenue, effectively use resources, and achieve target profits is measured by the financial dimension (Patiar et al., 2012; Sainaghi, 2010). Johnson and Kaplan (1991) and Sainaghi (2010) criticize for merely using financial measures as they are short-term and market-oriented, and suggest that non-financial measures like monitoring business process, customer and employee satisfaction, schedule attainment, and competitive performance, to name a few to be used along with financial measures while measuring a firm’s performance.

The study constructs have been operationalized based on the literature review presented above, as shown in Table 1.

Realizing relationships among the constructs

The literature review presented above has provided empirical evidence of the significant impact of TL and SCA on firm performance (Chen et al., 2015; Eckstein et al., 2015; Patiar & Wang, 2016; Tse et al., 2016) separately in different contexts. However, effective integration of TL to achieve SCA and lead to enhanced firm performance requires developing a framework that demonstrates the linkages among the study constructs. For example, quantifying and measuring the impact of schedule attainment and customer satisfaction on firm performance is insufficient. There is a strong relation between schedule attainment and customer satisfaction as there is a clear association between the rate and amount of schedule attainment and customer satisfaction. Therefore, to effectively implement the constructs, one needs to develop an insight into the association between the constructs. The isolated knowledge about the constructs might help delineate the impact on performance but will not contribute to implementing the same. Thus, the mere identification of the constructs of TL and SCA is incomplete support to the manager charged with implementation.

Identifying the study constructs and their connections reveals its strengths and limitations. This, if equated against the business rivals, can propose improvement prospects for firms and measures to overcome threats. As the accomplishment of one construct may lead to the attainment of another, it is always recommended to overlook the isolated measures and consider this holistic view. Thus, identifying the relative importance and the structural relationship among the constructs would enable effective management and implementation. For example, Sharma and Bhat (2014) developed a conceptual model of SCA showing the linkages between the enablers. They further classified the enablers into four categories by creating the driver-dependence diagram and suggesting that the enablers managers must focus on implementing an agile SC. Understanding the associations between the variables can demonstrate practical implications of academic concepts in real-world situations by taking feedback from professionals. Thus, the TISM modeling will enable academicians and practitioners to get a deeper understanding of the phenomenon, thereby assisting in implementing the same.

Research Questions and Objectives

While the extant literature has progressed well in identifying the drivers of firm performance in the domain of TL and SCA, the classification of these measures based on their relative importance to managers is lacking. Furthermore, there is little research that highlights the constructs' driver-dependence link, which can assist managers in managing the interactions that exist between them. After a thorough literature review and consultation with experts, the following research questions have been adopted for the study:

-

What constructs of TL and SCA lead to enhanced firm performance?

-

What is the relationship between these constructs?

-

What is the empirical soundness of the constructs' interconnections?

To answer the above research questions, the following objective has been formulated:

-

To construct a hierarchical model illustrating the dynamics between the elements of TL and SCA to enhance firm performance.

Methodology

While a thorough literature review was conducted to answer the first research question, in-depth interviews with production managers reporting to the CEO were conducted to assess the TL of the CEO, and the TISM technique was adopted to answer the second and third research questions. The Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM)/TISM approach helps enforce structure and direction on the complex relationships between system components (Sage, 1977), thus resulting in a complete hierarchical model. The model thus created reflects the structure of a complex problem using graphics and words in a carefully designed pattern. In the present context, several enablers can affect the firm's performance due to the leadership style of the CEO and SC practices followed by the firm. On the other hand, the direct and indirect linkages between the enablers represent the situation significantly more accurately than when the variables are independent. Thus, ISM/TISM provides insights into those relationships (Sharma & Bhat, 2014).

The study considers the majority of expert opinions to overcome the disadvantage of ISM, which is that expert opinions are not always consistent and transitive. The ISM and TISM techniques adopt graph theory's systematic, iterative application to provide practical interpretations of structural models (Asim & Nasim, 2022; Dwivedi et al., 2021; Sushil, 2012; Warfield, 1974; Yadav & Sagar, 2021). In ISM, only the nodes are interpreted, but links' interpretation is limited to the direction of the relation. The TISM technique addresses this flaw (Sushil, 2005). During the data-gathering phase, the experts (the production managers reporting to the CEO in the current study) explain how the constructs are related.

As the respondent's perceptions decide whether and how the variables are related, the TISM approach is interpretive. The procedure involved in the development of a model using the TISM approach are as discussed as follows:

-

A detailed analysis of the extant literature identifies the factors affecting the phenomenon.

-

The contextual relationship between identified factors is established by interviewing production managers at twelve SMEs and facilitating a pairwise comparison.

-

The outcome of the pairwise comparison between the factors is expressed as the aggregated matrix of expert responses.

-

The aggregated matrix is translated into a reachability matrix and tested for transitivity.

-

The matrix of reachability obtained above is split into levels.

-

Based on the relationship in the reachability matrix, a directed graph is drawn, and the transitive bonds are removed.

-

The resulting digraph is converted into a TISM model by converting the variable nodes into statements.

While the variable identification process for the current study happened through the literature review process, the next step is to delineate the relationship between the variables by interviewing SC managers at SMEs by facilitating pairwise comparisons between the identified variables. The variables identified for the TISM study are the operational constructs of TL, SCA, and firm performance, as shown in Table 1.

After developing the TISM model, in the second phase of the study, we decided to empirically validate the model by testing the strength of the linkages. According to Fine and Elsbach (2000), combining qualitative and quantitative research approaches produces a complete picture of a phenomenon and aids in developing a reliable, generalizable, and pragmatic theory (Shah & Corley, 2006). As a result, the TISM model of SCA is further validated in this study, increasing its acceptability and generality.

To this aim, we decided to empirically validate the developed TISM model by testing the strength of the linkages. Hence, a structured questionnaire was developed and circulated among production and SC managers of small-scale manufacturing industries and academic experts. The responses were recorded on a five-point Likert scale where one indicated ‘strongly disagree’ and five indicated ‘strongly agree.’ A total of 53 responses were collected. Managers from 46 different small-scale firms with rich experience in SC activities and seven academic experts specializing in the Operations and SCM domain responded to the survey.

The descriptive statistics that support the TISM framework's causal linkages, such as a higher mean (greater than 3) of the distribution, provide a reasonable basis for recognizing the framework as accurate (Srivastava & Sushil, 2013, 2017). The average value of each relationship in the framework was compared to a test value, which was taken to be a mean value > 3 (mean test value = 3), using the one-sample t-test. A mean value of more than 3 appears to be an acceptable test value for hypothesis testing because respondents' replies range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The primary hypotheses for validating the framework are as follows:

Null Hypothesis (H0): there is no significant difference between the observed mean and the specified mean value to accept the linkages among the factors in the model.

Alternate Hypothesis (H1): there is a significant difference between the observed mean and the specified mean value to accept the linkages among the factors in the model.

Thus, the linkages in the TISM model will be accepted if the value of the t statistic is significant, i.e., < 0.05 (95% confidence interval), showing greater acceptability of the linkages.

Research Context

Manufacturing SMEs in India was selected as the context of the research. They account for roughly 80% of India's industrial population, contributing to about 35% of gross industrial production and 40% of total exports in the manufacturing sector. They also employ many people across the country as they operate from semi-urban and rural areas. Hence, they are called the backbone of the Indian economy (SME Chamber of India, 2020). Global trends in classifying Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) reveal that classification varies significantly among jurisdictions and depends on the country's government regulations. Though a comparison of certain nations found that most of them use the number of employees to describe MSMEs, MSMEs in India are now defined based on the investment in plant and machinery/equipment. To promote ease of doing business, the government has implemented new turnover-based criteria for micro, small, and medium companies that will be beneficial to MSMEs beginning July 1, 2020.

Furthermore, issues such as resource scarcity, financial constraints, management and employee attitudes, and a lack of skill and expertise have made Indian SMEs record relatively slow progress toward global market challenges, new technology adoption, and gaining a competitive advantage through the adoption of modern operations strategies (Majumdar & Manohar, 2016). It is also noted that SMEs encounter difficulties managing their SC successfully. SMEs have an organizational structure primarily based on ownership. Few partners' or owners' attitudes and visions play critical roles in governance, strategic decision-making, and corporate growth (Thanki & Thakkar, 2019). Hence, it would be interesting to explore how the TL of the CEO would enable SCA among SMEs, thereby impacting firm performance (Table 2).

Results

Aggregated Matrix and Reachability Matrix

After operationalizing the study constructs, a pair-wise comparison was facilitated by interviewing production managers at twelve manufacturing SMEs. SMEs make up 95 percent of India’s total industrial units. The average experience of the interviewees was seven years in the production and SC domain. The profile of respondents and the firm considered for the study are shown in Table 3. Each interview lasted for a minimum of two hours, and the aggregated matrix is developed by summating the number of ‘Yes’ responses for the pair-wise comparison. The aggregated matrix is shown in Table 4. The reachability matrix is generated from the aggregated matrix if two-thirds of the experts have confirmed the relation between the pairs. Therefore, if two-thirds of the experts have established the relationship, we code such a pair as 1 in the reachability matrix; otherwise, it is codified as 0. The reachability matrix is then checked for transitivity, and the final reachability matrix is developed, as shown in Table 5. The procedure involved in developing the aggregated matrix, reachability matrix, development, and checking the correctness of the TISM model thus developed is outlined in Sushil (2018).

Level Partitions

The final reachability matrix is used to identify each factor's reachability set and antecedent set (Warfield, 1974). The reachability set consists of the factor itself and the other factors it may impact. In contrast, the antecedent set consists of the element itself and the different elements that will affect it. Finally, the intersection set is derived as the common factor in reachability and antecedent.

The top level of the TISM hierarchy comprises enablers with the same reachability and intersection set. Once the top-level element is identified (Table 6), it is separated from the other components, and the procedure is repeated to identify the element at the next level. This procedure is repeated until all the enablers present in the study are placed in the hierarchy (Table 7). The TISM digraph is developed from these level partitions (Fig. 1).

Further, the t-test discloses a higher mean score for the linkages (Table 8), and most of the associations have a p-value lesser than 0.05, making these relationships statistically significant. The higher mean values signify the importance of the TL of the CEO in establishing an agile SC among SMEs and attaining enhanced firm performance through the delivery schedule and customer satisfaction.

Discussions: TISM Model of Supply Chain Agility

According to Kaplan and Norton (1995), performance review is multi-faceted and includes monetary and non-monetary variables. This study contends that implementing an agile SC with the involvement of leaders is the key to attaining firm performance. The TISM framework supports the idea that factors related to TL (Inspirational Motivation, Intellectual Stimulation, and Individual Consideration) and SCA (Strategic Alertness, Strategic Response Capability, Operational Alertness, and Operational Response Capability) together contribute to firm performance (Schedule Attainment, Customer Satisfaction, and Financial Performance). All the constructs discussed above are modeled using TISM to depict the logical and hierarchical relations (Fig. 1). The model thus developed indicates that the elements of TL are driving forces for organizational activities that enhance outcomes. The hierarchical model built in this research appears like a ladder where an intermediate stage is SCA. Agility helps the SC adjust to dynamic market conditions by identifying competitor movements, current demand and supply fluctuations, and timely response. Firms incorporating agility in their SC will promptly meet customer requirements, thereby increasing customer satisfaction. The following sub-section discusses every construct and its association with another construct. The highly dependent construct is discussed first, followed by the construct with high driving power to show how one affects another.

Firm Performance (Financial and Non-Financial)

The performance factors are the financial and non-financial outputs of the strategic plan. As described by Kaplan and Norton (1995) in Balanced Score Card (BSC) and as observed from the developed TISM model, these factors are “lag factors” and get impacted by “lead factors.” While the essential economic measures are the return on investment, average profit, profit growth, return on sales, and operating ratio, the non-financial metrics include schedule attainment, customer satisfaction, competitive performance, etc., to name a few. While financial indicators are crucial, non-financial measures are typically more practical for day-to-day operations monitoring (Maskell, 1991). The TISM study illustrates that the TL of the CEO leads to the development of an agile SC that would absorb the uncertainty, thereby enhancing the firm's performance. For example, effective leadership may serve as a driver for SCA as they foresee the need to be adaptable to grasp market opportunities. A transformational leader emphasizes the need for agility by explaining the vision, assisting subordinates in developing a solution to problems innovatively, and using their strengths to address the challenge (Oliveira et al., 2012). The resulting flexibility may help absorb short-term market volatility and improve business performance (Eckstein et al., 2015). These are the impact of TL and SCA on the organization’s economic condition.

Supply Chain Agility

According to the current literature, SCA helps a company minimize production costs, improve customer satisfaction, eliminate non-value-added tasks, and maintain a competitive position in the market (Braunscheidel & Suresh, 2009; Li et al., 2008, 2009). To support more predictable upstream demand, this always involves lowering SC uncertainty to the maximum extent possible (Mason-Jones et al., 1999). On the other hand, uncertainty is impossible to eradicate from the SC. As a result, SC is faced with the challenge of accepting uncertainty while developing a plan that allows them to balance supply and demand. However, uncertainty can be reduced by being alert to changes and developing response capability (Li et al., 2008). Li et al. (2008) contend that SC can be agile by being attentive to changes and creating response capability at strategic and operational levels. While alertness at the strategic level is to be able to detect changes in the macroeconomic environment like political and social change, demographic shifts, and technological advancements, at the operational level, alertness is the ability to detect changes in demand and supply by assessing market trends, listening to customers, and tracking real-time order using point-of-sale data. Likewise, changes in supply can be detected by sharing real-time information with all the partners. Response capability is the ability of the firm to respond to change in distinctive ways (Teece et al., 1997). In terms of strategy, intelligent firms develop the agility to distinguish themselves from competitors by developing skills to rearrange SC capabilities quickly and flexibly to adapt to macroeconomic changes. At the operational level, however, response capability refers to the chain's ability to respond (preemptively or retrospectively) to shifts in supply and demand by developing new work management rules, reallocating resources for work in progress, and monitoring the timing and duration of work cycles appropriately and elastically (Li et al., 2009). Lastly, large organizations achieve agility by investing in infrastructural resources, and small firms can achieve it by having simple IT systems, close relationships with SC partners, and attentive leadership (Ngai et al., 2011).

Transformational Leadership Style

Leadership has always been the focus of organizational research, with scholars primarily exploring the impact leaders have on firm performance. However, extant literature comprises limited studies investigating the underlying reason for the performance outcome. This TISM analysis demonstrates that TL elements have the highest driving power influencing the other factors. Further, TL is most suited to managing operations in the current dynamic business environment (Bass et al., 2003). For example, in the dynamic business environment, firms must be agile to absorb fluctuations in demand. As leadership effects are higher in smaller firms (Miller, 1983), TL practiced by the CEO can act as a source of competitive advantage. Transformational leaders achieve agility by setting and communicating a vision, establishing strong values, and formulating guidelines to be followed in the face of a crisis. They exhibit confidence and power and make sound judgments in the interest of SC (Bruch & Walter, 2007). They foresee the uncertainty in the business environment and motivate SC members to adapt to the change by demonstrating great perseverance and commitment, upholding strong ethical ideals and moral conduct, sacrificing personal gain for the benefit of SC members, prioritizing the needs of SC members over their own, and share success and risk with SC members (Limsila & Ogunlana, 2008). These leaders develop a beautiful picture of the future and reinforce the need to be agile among SC members (Bi et al., 2012). Further, a transformational leader encourages SC members to be innovative and persuades them to be flexible by solving old problems in new ways (Erkutlu, 2008). Lastly, these leaders consider each SC member a unique firm and help them develop their capabilities by considering their maturity levels (Bi et al., 2012).

To put it another way, leaders establish meaningful relationships with each individual of the SC, pay attention to their growth and success needs, and act as a coach or mentors to help SC members reach their full potential in a supportive environment (Limsila & Ogunlana, 2008). These practices of the leader create an environment where SC members exhibit “extra effort” and commitment, thereby enabling the absorption of uncertainty (Blau, 1964; Mesu et al., 2013). While the established models measure firm performance, they do not assist managers in controlling and implementing the practices to enhance firm performance. However, the proposed TISM model assists managers in implementing the procedures for enhanced performance and elucidates what is happening along with why it is happening.

Implications

Large firms develop agile capabilities to compete in the dynamic business environment (Tse et al., 2016) by investing in infrastructure, sharing real-time information, and collaborating with SC members. On the other hand, small firms can develop SCA by having a simple IT infrastructure, close relations with suppliers, and good leadership (Ngai et al., 2011). Further, the importance of leadership in attaining agility and resulting performance has garnered attention from scholars. Thus, this study adopted an interpretive technique, integrated the factors of leadership style, SCA, and firm performance, and tested the same empirically in the context of Indian manufacturing SMEs. The study has implications for theory and practice. Theoretically, the study is among the earliest to integrate the concepts of TL, SCA, and firm performance and bring out the associations between them by capturing the expert thought process.

Practically, the developed TISM model helps management at three levels: leadership practices, and strategic and operational SC practices. On the leadership practices front, the model suggests that CEOs of small firms lead by example as leaders are at the heart of operations in SMEs and drive every process and SC activity. Leaders can induce agility in SME SC by setting and communicating a vision that is to be attained by SC members collectively. By convincing SC members that the vision is achievable and mentoring them individually by considering their abilities, the CEO could motivate them to achieve the target. These practices by the CEO would lead to “extra effort” by the SC members to go beyond their regular course of work, thereby establishing a committed and flexible workforce (Mesu et al., 2013; Organ, 1988). At the strategic level, visionary leaders can envision shifts in the macroeconomic environment and develop capabilities better than competitors to absorb the changes; at the operational level, leaders must motivate managers to monitor changes in the operating environment and encourage innovative response techniques. The agile capability thus developed along with a flexible and committed workforce would enable firms to absorb changes in demand and supply, enhancing delivery performance and consequently affecting the firm performance. Lastly, the model would assist the management in allocating adequate time and resources to essential factors that drive implementing an agile chain and enhanced performance.

Conclusions and Limitations

Several studies in extant literature have explored the impact of TL and SCA on firm performance (Eckstein et al., 2015; Patiar & Wang, 2016; Ra’ed et al., 2016; Srinivas & Waheed, 2015). However, there is a shortage of studies that present a framework for comprehending the criticality of the constructs of TL and SCA and their interconnections that would impede the implementation by managers. This study identifies the elements of TL, SCA, and firm performance through a thorough literature review and imposes order and direction on the same using the TISM technique. A hierarchical model is developed by capturing the expert thought process and is empirically validated in the context of manufacturing SMEs in India. The model portrays a method using which manufacturing SMEs can enhance their performance by inducing agility in SC through a transformative leader’s vision. The developed TISM model assists managers in assessing, monitoring, controlling, and updating the implementation process. In addition to the interpretive tool, the study provides methodological value through triangulation. The TISM framework's interpretation of nodes and links is a unique exercise that explains not only the "what" and "how" but also the "why" of theorization.

The study developed a framework by modeling the elements of TL and SCA to enhance firm performance among SMEs, but the results are not without limitations. Future researchers can further validate the framework in large organizations for generalizability. To strengthen the acceptability and application index of the research findings, a second qualitative or quantitative study with expert feedback could be done. While a one-sample t-test validated the model in the current research, scholars in the future can perform correlation analysis to identify and understand the overlapping variables. Finally, while respondents to the ISM survey may have various perspectives, the framework was developed with the predominant position in mind. This response constraint can be improved through multiple interactions with the respondents.

References

Agarwal, A., Shankar, R., & Tiwari, M. K. (2007). Modeling agility of supply chain. Industrial Marketing Management, 36(4), 443–457.

Alzoubi, Y. I., & Gill, A. Q. (2022). Can agile enterprise architecture be implemented successfully in distributed agile development? empirical findings. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 23(2), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-022-00298-w.

Asim, M., & Nasim, S. (2022). Modeling enterprise flexibility and competitiveness for Indian pharmaceutical firms: A qualitative study. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 23(4), 551–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-022-00318-9.

Ates, A., & Bititci, U. (2011). Change process: A key enabler for building resilient SMEs. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18), 5601–5618.

Bantel, K. A., & Jackson, S. E. (1989). Top management and innovations in banking: Does the composition of the top team make a difference? Strategic Management Journal, 10(S1), 107–124.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. The Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Sage Publication.

Bass, B. M., Avolio, B. J., Jung, D. I., & Berson, Y. (2003). Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(2), 207.

Bi, L., Ehrich, J., & Ehrich, L. (2012). Confucius as transformational leader: Lessons for ESL leadership. International Journal of Educational Management, 26(4), 391–402.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

Braunscheidel, M. J., & Suresh, N. C. (2009). The organizational antecedents of a firm’s supply chain agility for risk mitigation and response. Journal of Operations Management, 27(2), 119.

Bruch, H., & Walter, F. (2007). Leadership in Context: Investigating hierarchical impacts on transformational leadership. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 28(8), 710–726.

Cao, M., & Zhang, Q. (2011). Supply chain collaboration: Impact on collaborative advantage and firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 29(3), 163–180.

Chen, I. J., & Paulraj, A. (2004). Understanding supply chain management: Critical research and a theoretical framework. International Journal of Production Research, 42(1), 131–163.

Chen, A. S. Y., Bian, M. D., & Hou, Y. H. (2015). Impact of transformational leadership on subordinate’s EI and work performance. Personnel Review, 44(4), 438–453.

de Oliveira, M. A., Possamai, O., Dalla Valentina, L. V., & Flesch, C. A. (2012). Applying Bayesian networks to performance forecast of innovation projects: A case study of transformational leadership influence in organizations oriented by projects. Expert Systems with Applications, 39(5), 5061–5070.

Dubey, R., Altay, N., Gunasekaran, A., Blome, C., Papadopoulos, T., & Childe, S. J. (2018). Supply chain agility, adaptability and alignment. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 38(1), 129–148.

Dove, R. (2005). Agile enterprise cornerstones: Knowledge, values, and response-ability. In R. Baskerville (Ed.), Business agility and information technology diffusion. Springer.

Dwivedi, A., Agrawal, D., Jha, A., Gastaldi, M., Paul, S. K., & D’Adamo, I. (2021). Addressing the challenges to sustainable initiatives in value chain flexibility: Implications for sustainable development goals. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22(Suppl 2), S179-S197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-021-00288-4.

Eckstein, D., Goellner, M., Blome, C., & Henke, M. (2015). The performance impact of supply chain agility and supply chain adaptability: The moderating effect of product complexity. International Journal of Production Research, 53(10), 3028–3046.

Erkutlu, H. (2008). The impact of transformational leadership on organizational and leadership effectiveness. Journal of Management Development, 27(7), 708–726.

Fine, G. A., & Elsbach, K. D. (2000). Ethnography and experiment in social psychological theory-building: Tactics for integrating qualitative field data with quantitative lab data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36(1), 51–76.

Finkelstein, S., & Hambrick, D. C. (1990). Top-management-team tenure and organizational outcomes: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Administrative Science Quarterly, pp. 484–503.

Govindarajan, V., & Trimble, C. (2012). Reverse innovation: Create far from home, win everywhere. Harvard Business Press.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193.

Holsapple, C., & Jones, K. (2005). Exploring secondary activities of the knowledge chain. Knowledge and Process Management, 12(1), 3–31.

Huo, B., Qi, Y., Wang, Z., & Zhao, X. (2014). The impact of supply chain integration on firm performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 19(4), 369–384.

Johns, H. E., & Moser, H. R. (2001). From trait to transformation: The evolution of leadership theories. Education, 110(1), 115–122.

Johnson, H. J., & Kaplan, R. S. (1991). Relevance lost: The rise and fall of management accounting. Harvard Business School Press.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1995). Putting the balanced scorecard to work. Performance Measurement, Management, and Appraisal Sourcebook, 66(17511), 68.

Keller, R. T. (2006). Transformational leadership, initiating structure, and substitutes for leadership: A longitudinal study of research and development project team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(1), 202–214.

Kumar, R., Singh, R. K., & Shankar, R. (2015). Critical success factors for implementation of supply chain management in Indian SMEs and their impact on performance. IIMB Management Review, 27(2), 92–104.

Lee, H. L. (2004). The triple—A supply chain. Harvard Business Review, 82(10), 102.

Li, X., Chung, C., Goldsby, T. J., & Holsapple, C. W. (2008). A unified model of supply chain agility: The work-design perspective. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 19(3), 408–435.

Li, X., Goldsby, T. J., & Holsapple, C. W. (2009). Supply chain agility: Scale development. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 20(3), 408–424.

Limsila, K., & Ogunlana, S. (2008). Performance and leadership outcome correlates of leadership styles and subordinate commitment. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 15(2), 164–184.

Majumdar, J. P., & Manohar, B. M. (2016). Why Indian manufacturing SMEs are still reluctant in adopting total quality management. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 17(1), 16–35.

Marić, J., & Opazo-Basáez, M. (2019). Green servitization for flexible and sustainable supply chain operations: A review of reverse logistics services in manufacturing. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 20(Suppl 1), S65–S80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-019-00225-6.

Maskell, B. H. (1991). Performance measurement for world class manufacturing. Productivity Press Inc.

Mason-Jones, R., Naylor, B., & Towill, D. R. (1999). Lean, agile, or leagile-matching your supply chain to the marketplace. In Proc. 15th int. conf. prod. res., Limerick (pp. 593–596).

Mesu, J., Van Riemsdijk, M., & Sanders, K. (2013). Labour flexibility in SMEs: The impact of leadership. Employee Relations, 35(2), 120.

Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770.

Miller, D., & Toulouse, J. M. (1986). Chief executive personality and corporate strategy and structure in small firms. Management Science, 32(11), 1389–1409.

Nadkarni, S., & Herrmann, P. O. L. (2010). CEO personality, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: The case of the Indian business process outsourcing industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5), 1050.

Neely, A., Gregory, M., & Platts, K. (1995). Performance measurement systems design: A literature review and research agenda. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 15(4), 80–116.

Ngai, E. W., Chau, D. C., & Chan, T. L. A. (2011). Information technology, operational, and management competencies for supply chain agility: Findings from case studies. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 20(3), 232–249.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior. Lexington Books.

Overstreet, R.E., Hanna, J.B., Byrd, T.A., Cegielski, C.G. & Hazen, B.T. (2013). Leadership style and organizational innovativeness drive motor carriers toward sustained performance. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 24(2), pp. 247–270.

Pagell, M. (2004). Understanding the factors that enable and inhibit the integration of operations, purchasing and logistics. Journal of Operations Management, 22(5), 459–487.

Pandiyan Kaliani Sundram, V., Razak Ibrahim, A., & Chandran Govindaraju, V. G. R. (2011). Supply chain management practices in the electronics industry in Malaysia: Consequences for supply chain performance. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 18(6), 834–855.

Patiar, A., Davidson, M., & Wang, Y. (2012). The interactive effect of market competition and total management practices on hotel department performance. Tourism Analysis, 17(2), 195–211.

Patiar, A., & Wang, Y. (2016). The effects of transformational leadership and organizational commitment on hotel departmental performance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(3), 586–608.

Prabhu, M., & Srivastava, A. K. (2022). Leadership and supply chain management: A systematic literature review. Journal of Modelling in Management (Ahead of Print). https://doi.org/10.1108/JM2-03-2021-0079

Pradabwong, J., Braziotis, C., Tannock, J. D., & Pawar, K. S. (2017). Business process management and supply chain collaboration: Effects on performance and competitiveness. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 22(2), 107–121.

Prajogo, D. I., Mcdermott, P., & Goh, M. (2008). Impact of value chain activities on quality and innovation. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 28(7), 615–635.

Ra'ed, M., Obeidat, B. Y., Tarhini, A. (2016). A Jordanian empirical study of the associations among transformational leadership, transactional leadership, knowledge sharing, job performance, and firm performance: A structural equation modeling approach, Journal of Management Development, 35(5).

Sage, A. (1977). Interpretive structural modeling: Methodology for large-scale systems. McGraw-Hill.

Sainaghi, R. (2010). Hotel performance: State of the art. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(7), 920–952.

Settembre-Blundo, D., González-Sánchez, R., Medina-Salgado, S., & García-Muiña, F. E. (2021). Flexibility and resilience in corporate decision making: a new sustainability-based risk management system in uncertain times. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22(Suppl 2), S107-S132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-021-00277-7.

Shah, S. K., & Corley, G. K. (2006). Building better theory by bridging the quantitative-qualitative divide. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 2322–2380.

Sharma, S. K., & Bhat, A. (2014). Modeling supply chain agility enablers using ISM. Journal of Modelling in Management, 9(2), 200–214.

Simatupang, T. M., & Sridharan, R. (2008). Design for supply chain collaboration. Business Process Management Journal, 14(3), 401–418.

Singh, R. K., Joshi, S., & Sharma, M. (2020). Modeling supply chain flexibility in the Indian personal hygiene industry: An ISM-Fuzzy MICMAC approach. Global Business Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150920923075

SME Chamber of India. (2020). Retrieved September 08, 2022, from https://www.smechamberofindia.com/about-msme-in-india.php

Rao, S., & Abdul, W. K. (2015). Impact of transformational leadership on team performance: An empirical study in UAE. Measuring Business Excellence, 19(4), 30–56.

Srivastava, A. K., & Sushil. (2013). Modeling strategic performance factors for effective strategy execution. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 62(6), 554–582.

Srivastava, A. K., & Sushil,. (2017). Alignment: The foundation of effective strategy execution. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 66(8), 1043–1063.

Sushil,. (2005). Interpretive matrix: A tool to aid interpretation of management and social research. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 6(2), 27–30.

Sushil,. (2012). Interpreting the interpretive structural model. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 13(2), 87–106.

Sushil. (2018). How to check the correctness of total interpretive structural models? Annals of Operations Research, 270(1–2), 473–487.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capability and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533.

Thakkar, J., Kanda, A., & Deshmukh, S. G. (2012). Supply chain issues in Indian manufacturing SMEs: Insights from six case studies. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 23(5), 634–664.

Thanki, S., & Thakkar, J. J. (2019). An investigation on lean–green performance of Indian manufacturing SMEs. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 69(3), 4879–5517.

Tse, Y. K., Zhang, M., Akhtar, P., & MacBryde, J. (2016). Embracing supply chain agility: An investigation in the electronics industry. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 21(1), 140–156.

Um, J. (2017). Improving supply chain flexibility and agility through variety management. The International Journal of Logistics Management, 28(2), 464–487.

Wadhwa, S., & Rao, K. S. (2004). A unified framework for manufacturing and supply chain flexibility. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 5(1), 29–36.

Wang, G., Oh, I.-S., Courtright, S. H., & Colbert, A. E. (2011). Transformational leadership and performance across criteria and levels: A meta-Analytic review of 25 years of research. Group and Organization Management, 36(2), 223–270.

Warfield, J. (1974). Developing interconnected matrices in structural modeling. IEEE Transcription Systems, Men and Cybernetics, 4(1), 51–81.

Weiner, N., & Mahoney, T. A. (1981). A model of corporate performance as a function of environmental, organizational, and leadership influences. Academy of Management Journal, 24(3), 453–470.

Wiengarten, F., & Longoni, A. (2015). A nuanced view on supply chain integration: A coordinative and collaborative approach to operational and sustainability performance improvement. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 20(2), 139–150.

Yadav, A., & Sagar, M. (2021). Modified total interpretive structural modeling of marketing flexibility factors for Indian telecommunications service providers. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 22(4), 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-021-00278-6.

Zhang, X., Van Donk, D. P., & van der Vaart, T. (2016). The different impact of inter-organizational and intra-organizational ICT on supply chain performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 36(7), 803–824.

Zhao, L., Huo, B., Sun, L., & Zhao, X. (2013). The impact of supply chain risk on supply chain integration and company performance: a global investigation. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 18(2), 115–131.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal. We received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Prabhu, H.M., Srivastava, A.K. CEO Transformational Leadership, Supply Chain Agility and Firm Performance: A TISM Modeling among SMEs. Glob J Flex Syst Manag 24, 51–65 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-022-00323-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-022-00323-y