Abstract

Fisher movement in the pursuit of fish is a well-established truism. In this paper, we explore the motivations and mechanisms deployed for internal migration within the fishing sector in coastal Tamil Nadu, rather than only on the seas, as a strategy for both economic and social mobility. Marine fisheries in India is a caste-based occupation, with its own social and political hierarchy, responsible for the governance and management of common resources. For those belonging to the subordinate fishing castes, excluded from decision-making processes, migration is an important strategy for gaining economic resources, social power and recognition as skilled and successful marine fishermen. Using qualitative research methods, the paper explores the migration of fishermen from Rajakuppam, a small fishing village in Cuddalore district, belonging to such a subordinate fishing caste, to Kasimedu, in the capital city of Chennai, the largest fishing harbour in the state of Tamil Nadu. We find that family and its social organization, in particular kinship and marriage ties, brokered by senior women, are significant factors in facilitating successful migration. Recognizing women’s contributions to the sector, both direct and through their social reproductive and networking activities, invisible in both the larger maritime literature and production-centric fisheries’ policy-making, is crucial for achieving wellbeing and sustainability outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The village is like an island. We are scared of another tsunami, as the landward side is fenced by industry, and we are surrounded by water on the other three. 20 years have passed, and despite protesting several times, with demands for a shelter and other infrastructure, nothing much has changed. The jetty constructed by the company has led to high levels of sea erosion; we have little docking space for our craft and have lost access to near-shore fishing grounds. The water in the village has turned saline (President, Ur Panchayat, RajakuppamFootnote 1).

The quote from a village leader points to the growing risks and uncertainties of life and livelihoods in a coastal village, here named Rajakuppam, in Cuddalore district of Tamil Nadu, India. Alongside protests, migration is now a recognized strategy for coping with poverty and risk, similar to other poor and natural resource-dependent communities globally (De Haan 1999; Kusakabe 2020). Migration takes various forms, from individual to family migration, and occurs at a variety of scales, a major one being rural to urban migration, the subject of this paper.

Central to the marine fisheries sector is movement and migration in search of better fishing grounds. Migration, however, is rapidly increasing, triggered now by a complex range of factors: the seasonal depletion of fish resources, climate change and environmental hazards, conflict, as well as changes in the global political economy (Islam and Herbeck 2013). The Blue Revolution agenda, starting in the 1950s and 1960s, with its focus on mechanization of smaller craft, introduction of bottom trawling and purse seining, alongside the development of necessary infrastructure, leading more recently to a push for ‘blue growth’, with its emphasis on export promotion, infrastructure development and technological advancement, has created a further driver for fisher movement to areas better resourced than their own (Immanuel and Narayanan 2015).

In this paper, we explore the migration of fishermen from Rajakuppam, belonging to a fishing caste perceived as subordinate in the region, to Kasimedu, Chennai, the largest fishing harbour in the state. Their physical movement for earning a living and livelihood security is also a struggle for social mobility, an attempt to establish their status as skilled and successful marine fishermen, within the hierarchy of fisher castes in Tamil Nadu’s Coromandel Coast. The process however was not easy, with intense resistance and opposition from the local fishers at the destination. They countered this opposition through hard work, and establishing a unique social organisation, the vagaira, based on bonds between siblings and their marital families. They have been able to build substantial physical and social capital, constructing good houses and providing quality higher education to their children, through the moral and financial support they have assured each other, especially in times of crisis.

This paper seeks to explore the meanings of ‘success’ in the context of voluntary fisher migration by asking three questions: (a) What are the key motivations and mechanisms of migration for fishers from Rajakuppam village to Chennai? (b) In what ways does family organization facilitate or hinder such migration? and (c) What impact does family organization have on the social identity and well-being of the fishers? Recognizing that fisher communities are not unified entities, but reflect social and economic hierarchies, we focus here primarily on the migration experiences of migrant settler households who while starting as labourers and crew members, have established themselves as mechanized boat-owners. Mobility strategies and wellbeing outcomes of women-headed households, largely immobile, have been discussed elsewhere (Azmi et al. 2021).

This paper is divided into seven sections. Following this introduction, which sets out our primary focus and research questions, we turn in the “Theoretical Framework” section to setting out our conceptual starting points. The “Methodology and context” section explains the methodology and an overview of contexts in both the origin and destination sites. The “Motivations for Migration” section details the motivations for migration, while the “Mechanisms for Successful Migration” section explores the mechanisms involved in the migration process including the forms of migration, the struggles to survive, and the role and contributions of the social organization represented by the family group (vagaira). The “Social organisation and wellbeing outcomes” section explores the impacts of these mechanisms, especially social organization, on the identity and wellbeing of the fishers as ‘successful’ migrants. The final “Conclusion” section concludes.

Theoretical framework

Migration is central to fisher livelihoods, yet the mechanisms are often not easy to navigate and outcomes not predictable. Mobile fishers encounter competition and at times conflict with residents in destination locations (Vanniasinkam et al. 2020), evident also in the current case study. Most established work on migrant labour, focuses largely on migrant crew, usually employed as ‘unfree labour’, and their exploitative working conditions (Vandergeest and Marschke 2019). Research on (voluntary) aspirational migration within the fishing sector in South and south-east Asia, its nature, drivers, and wellbeing outcomes, and how these are gendered, is only recently emerging (Lund et al. 2020). Men engage with such labour migration not just for their everyday survival, but as a pathway for accumulating capital for investments in their own boats (Rao and Manimohan 2020). Yet as men migrate, women involved in post-harvest fisheries activities may lose access to fish and be obliged to abandon their occupation (Aswathy and Kalpana 2018), with potential negative effects on gender relations. Women, nevertheless, continue to play a central role in the social reproduction of the fishing enterprise, and though this remains largely invisible and unacknowledged, provides them space for exercising agency and negotiating their own social positions. Migration in this context is not a single event of moving across a pre-defined border, but is, rather, a longer-term process of decision-making, execution, and integration (Erlinghagen et al. 2019).

We draw on the idea of ‘mobility’ as a form of ‘capital’ — a livelihood resource for people to get around the spatial and material constraints that bind them. Mobilities are diverse and signify a range of social relations, duties and obligations between people and families across space and time (Urry 2007). Mobility can compensate for other capital deprivations, whether economic, social or cultural, and in fact contribute to augmenting these other forms of capital, providing people with opportunities for diversification, but equally reshaping one’s sense of self in terms of everyday activities, interpersonal relations, as well as connections with the wider world (Rao 2014). In this case, physical or spatial mobility, as seen in different forms of migration, appears to have contributed both to wealth accumulation and an improvement in social standing for a group of people placed low in the caste hierarchy.

Mobility as a concept is useful for studying both the complex movements of people, objects and information across physical boundaries, and the meanings and representations attached to such movements (Urry 2007: 24). Cresswell and Merriman (2011) emphasize that mobility remains gender-differentiated, with women’s mobility not just circumscribed by discriminatory practices, but policy agendas also overlooking women’s needs, a point explored by Rao (2001) in the context of rural, forest-dependent women in India. Race and class inequalities, and caste in the case of India, are other crucial axes shaping the freedom to move and the right to stay and work in particular places. Marine fisheries in India are a caste-based profession, with community leaders mediating inclusion and exclusion, especially through their control over community resources (Weeratunge et al. 2014). While migrants may be admitted as labour, there is resistance to their becoming boat-owners, emphasizing the centrality of caste identity and wider social relations to mobility processes.

In this paper, we argue that mobility itself appears to have been facilitated by strong social bonds based on kinship and marriage ties, emphasizing the critical role of social relationships in mediating ‘success’. Social capital has been defined as the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual or group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992). For marginalized groups, with less access to formal institutions, family and community networks are key to accessing skills and resources needed to join the economic mainstream and enjoy higher returns (Moser 1996; Narayan 1995). Building on work by Granovetter (1973) on the strength of social ties, Gittell and Vidal (1998) recognize that strong intra community ties give families and communities a sense of identity and support, what they term “bonding” social capital. Apart from material resources, psychological, emotional and informational costs are also greatly reduced when migrants have access to family and friends at the destination (Bodvarsson et al. 2015). In their analysis of poor communities in rural areas of northern India, Kozel and Parker (2000) report that such social groups serve vitally important protection, risk management, and solidarity functions.

Both internal and international migration are facilitated by networks of family and friends, who provide the new migrants with food, a place to live, and contacts for securing work (McKenzie and Rapoport 2007; Munshi and Rosenzweig 2016). Such networks rely on principles of trust and expectations of reciprocity (Coleman 1988; Garip 2008). As we find in this paper, while key to ‘successful’ mobility of fishers perceived to be of lower status, these same strengths can also become burdensome for those who may be poorer, risk-averse or subject to other disabilities, constraining in turn their mobility strategies (Woolcock and Narayan 2000; Shelton 2017).

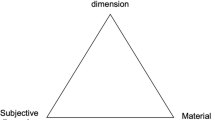

While mobility then embraces both spatial and social change, we deploy the concept of social wellbeing to assess notions of ‘success’. Wellbeing is broadly understood as a measure of human development (Sen 1999), including the pathways for negotiating and exiting from a life of poverty and vulnerability (Johnson et al. 2018). While we focus on boat-owning households as successful migrants, boat ownership alone is not a measure of success. White (2008) conceptualizes wellbeing as including three interconnected dimensions — the material, relational and subjective. In this approach, in addition to material assets, income and livelihood security, the quality of social relationships, the perceptions of happiness and of living a fulfilling life, are seen as important (White 2008; Johnson et al. 2018). Here, social status, education of the children, arranging hypergamous marriages, living amicably with family, are all dimensions of wellbeing that contribute to ‘success’. While this process is influenced by dynamic changes in individual and contextual determinants, forms of family and social organization appear to be key.

Methodology and context

This pilot study draws on a range of methods, mainly qualitative, to understand at a micro-scale the processes and mechanisms underlying the internal migration of fishers and the pathways to ‘success’ both in terms of social mobility and social wellbeing. Initially, we set out to study the dynamics of internal migration within the fishing sector and its links to coastal transformations. However, during the fieldwork, we found a near-universal attribution of success in the migration process to the formation and support of the vagairas. Finding little mention of such groups in the literature, we decided to focus on exploring the role and contribution of vagairas to the wellbeing of migrant fisher households and their mobility trajectories. Preliminary focus group discussions and key informant interviews revealed the existence of six vagairas amongst the 65 migrant settler households from Rajakuppam, the study village. We conducted an in-depth study of one of them, the Annamalai Vagaira, also representing the first migrants to Chennai from Rajakuppam. We had informal discussions with members of other groups and interviews with two fishers who had left their vagaira groups.

A total of 15 men and 10 women were interviewed, differentiated by boat ownership and labouring status, across households who were fully migrant/resident, with men and women at the same location, and those where the men were migrant and the women stayed in the village. Details of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Given our interest in the role of the vagaira on intra and intergenerational changes in social identity and well-being, 4 key informants were selected for in-depth interviews from three generations of the Annamalai vagaira: an elderly woman, founder of the group, belonging to the first generation, two men from the second generation, and one from the third. They represent the category of mechanized boat owners. Life histories with senior women and men helped understand the history of migration and its social organization. We also interviewed one male mechanized boat owner who was not a member of a vagaira, and one who had left the group and returned to the village, to understand the roles, and equally challenges arising from such social organization. Given the nature of the study, we conducted linked interviews across two locations, Rajakuppam and Chennai.

We also interviewed fishing labour across both sites to understand their perspective on the vagaira groups, and how these have impacted their lives as migrant workers, but equally their contributions to the development of the village. To understand this larger context of change in the village, we purposively interviewed 5 men and women from small scale fishing households and 3 fish vendors, women heading their own households.

All the interviews were conducted in the local language, Tamil, and recorded with permission of the respondents. They were transcribed, manually coded in line with the themes of interest, and analysed. In addition, secondary data from the CMFRI Census 2016 for Tamil Nadu was used to provide some context to the study, especially the socio-economic profile of the settlement, ownership of crafts and gear, fishing practices and gender participation in fisheries activities.

Study locations

Rajakuppam

Cuddalore district, with a coastline of 57.5 km, comprises of 43 fishing villages. Fishing, clustered around three urbanizing harbours, was the mainstay for a large proportion of the population till the establishment of the industrial estate (SIPCOT) in the district in 1975. The resulting growth of industries and power plants has had an impact on coastal land use and erosion, in addition to problems of pollution and the destruction of near-shore habitat (Menon et al. 2023). The construction of jetties and pipelines for importing raw materials and discharge of waste have not just occupied coastal lands and waters, but interfere physically with fishing operations, alongside affecting the health of fish stocks and marine ecosystems. Rajakuppam has lost about half its shoreline (250 m) following the establishment of the Nagarjuna Oil Corporation Ltd (NOCL), placing 20% of its area under the hazard line (Sriganesh et al. 2015; Saxena et al. 2013). As compensation, the local fisher councils have negotiated deals, whereby the industries make annual contributions to temple festivals and reserve a limited number of low-paying jobs for people from these hamlets.

Rajakuppam comprises of 230 fisher families, 94% classified as lying Below the Poverty Line (BPL) (CMFRI-DoF 2020). Compared to the district as a whole, a larger proportion of households lives in temporary (kutcha) houses and don’t have access to tapped drinking water or sanitation facilities. Almost 40% depend on bore wells, which according to the Panchayat President quoted at the start, have now turned saline (Appendix Table 2). Interestingly, the overall literacy rate of Rajakuppam at 71% is 13 percentage points higher than the district, driven perhaps by the threats to their traditional livelihood and the need to diversify, alongside the development of a host of educational institutions and commercial establishments in the district. Gender differences in education, in favour of girls, emerge beyond high school (Appendix Table 4), as relative poverty in the village compared to the district perhaps drives young men to employment earlier. At present over 30 young men have migrated to a range of destinations in the Gulf or South-east Asia to earn money.

The village has 37 fishing craft; over half of them non-motorised, owned by 44 families, and no mechanized boats (Appendix Table 3) (CMFRI-DoF 2020). Several households are however engaged in trawl fishing, most of them operating outside the district, from Chennai harbour, and are the focus of this study. In terms of participation in the fishing enterprise, 74% of active women are involved in marketing fish and 24% in processing, while a majority 86.4% of men are fishing, whether as small boat owners or fishing labour (Appendix Table 5). Of the 50 or so women involved in fisheries, a middle-aged woman, Suma, noted that it was mostly women like her who were involved in fresh fish vending, due to the non-availability of fish. Young widows and elderly women engage in dry fish vending for their survival. Migration and the improvement in both socio-economic status and education, has meant that many women have withdrawn from post-harvest fisheries activities.

Kasimedu, Chennai

The Royapuram fishing harbour, also known as Chennai or Kasimedu Fisheries Harbour, constructed in 1975 (commissioned in 1984), with a ground area of 24 hectares and a 495-m long jetty, is the largest mechanized boat fishing port in Tamil Nadu. Of the 1395 registered boats, approximately 800 are operational (Bavinck et al. 2015). Engaged in multi-day fishing voyages for both inshore and deep-sea trawling (for shrimps and lobsters) (Devaraj et al. 1996), the city contributes substantially to the export of marine products from India (Mohanraj et al. 2012).

Ownership of boats is however concentrated, with most owners possessing more than one boat (in 2014 the maximum that an owner could effectively handle was 6–7 boats). Kasimedu has now become a hub for migrant fishers from other parts of the State. Around 60 to 70 Rajakuppam fishers have moved to Kasimedu, of whom 25 families own 85 mechanized boats, constituting nearly 10% of the operational boats. Each boat employs at least 10 fishing labour and a driver per multi-day fishing trip. These migrant settlers live in a single hamlet and have constituted their own management group, similar to the Ur Panchayat (traditional village governance body), to negotiate resource access and resolve conflicts within and beyond the group.

Motivations for migration

A range of factors — biophysical, technological, economic and socio-cultural — have motivated the migration of fishers from Rajakuppam to Chennai (Fig. 1). While coastal erosion and frequent natural hazards exposed the fishers to risk (Bavinck 2020), the lack of infrastructure and poor marketing facilities made the situation in their home village precarious. In contrast, Chennai offered better facilities and prices, easy access to skilled fishing labour, a safe and protected place for berthing the mechanized boats, and scope for multiday fishing. Mr KV, 55, a key informant, noted: “In 1975 the only mechanized boat-owning family from Rajakuppam was ours. As there was no safe boat-berthing facility in Cuddalore, my father moved to Chennai”. Mr Kasi, 49, a mechanized boat owner settled in Kasimedu, added:

When mechanised fishery was picking up in Chennai, the scenario in our village and district was grim. Fishing was possible only at particular times; still the waves damaged our boats. We had to physically carry the Kattumaram on our shoulders to the sea and pull it back on our return. Fish catch too had to be transported as head loads to the market or selling point. At times, instead of landing in our own village, the boat was taken elsewhere by changes in wind directions. Now we have engines but those days our sailing boats were entirely dependent on the wind. Kasimedu did not have these problems; rather it offered better facilities for fishing and the prices were better too.

With the modernisation of fisheries, Chennai fishers were using advanced craft, gear, engines, and had gained knowledge and skills in deep–sea fishing. The Rajakuppam fishers were still using beach-landing boats for near-shore fishing (within 3 nautical miles). Mr. KV’s family, who bought the first mechanized boat, also found better transport and marketing facilities in Chennai and access to skilled labour enabled them to earn remunerative prices rather than ending up with distress sales, as they often did at home.

Alongside these push and pull factors, a primary motivation for migration came from their social position in the caste hierarchy within fishing communities. There are two major fishing castes in the district — the Pattinavar and the Paravatharajakulam. While the former inhabit the northern and southern parts of the district, the latter are concentrated in the central part and constitute the population of Rajakuppam (Bavinck 2020). The Parvatharajakulam, classified as a most backward caste (MBC), are seen by the dominant Pattinavars as inland, near shore and backwater fishers, hence lower in status and skills than the marine fishers (Thurston and Rangachari 1987). The Pattinavars control decision-making in the fishermen’s cooperative societies as well as the traditional coastal resource governance bodies (Ur panchayat). A local fisher leader commented: “While we are members of the fisheries cooperatives, we seek to identify ourselves as Pattinavars in the caste certificates. This is a marker of higher status”.

Constrained in their aspirations by caste-determined structures, the Rajakuppam fishers sought to prove through their migration that caste disparities had nothing to do with their fishing capabilities. While class and gender differentiation persist within the group, depending on the type of boat owned or not, or marital status, with widows and wives of disabled men often at the bottom of the social hierarchy, caste identity was perceived as the most significant driver of social mobility and status acquisition. In fact, sensitivity to their caste identity and the caste-based competition at their destination, contributed to shaping their strategy of building on family and kinship ties to confront challenges to their survival and indeed ‘success’.

Mechanisms for successful migration

Patterns of migration

Migration can take different forms — internal (rural to rural or rural to urban) or international (King et.al., 2008). In Rajakuppam, one sees both forms, with interconnections between them. Figure 2 reveals, first, a form of step migration, wherein migrants from the village moved to an urban setting within their own state, Chennai, before subsequent international migration to Singapore, the Gulf and Middle Eastern countries. The period spent in Chennai as fishing labour helped them save money and build the social linkages needed for international migration, validating Skeldon's (2004) view that internal and international migration are alternative strategies that depend upon the relative stages of long economic cycles.

Secondly, we also find patterns of circular migration; with some fishers directly migrating overseas from Rajakuppam, and others internally to Chennai. Mr. Raj, President of the Ur Panchayat, confirmed:

40 years ago, life was difficult in the village, there was no hospital or facility for education, and income from fishing was poor. While a few went to Chennai to work as fishing labour on trawl boats, many including myself went to Bahrain or other countries, working as labourers on cargo ships, loading and unloading goods. I returned to the village due to poor health.

Amongst the international migrants, some like Mr. Raj returned to the village and others to Kasimedu, especially those supported by their family groups to invest in mechanized fishing. In some cases, while the migrant was overseas, his immediate family moved internally with their kin-group, creating a favourable environment for the international migrant to return to Chennai. However, all of them maintained village homes and their rural roots.

Many of the boat owning settlers from Rajakuppam were first international migrants, working as fishing labour in Qatar, Saudi and Dubai. A few went to Bahrain and Singapore as construction labour – all of them earning between Rs. 20000 to Rs. 50000 per month. They faced many problems. In Kasimedu, many of their kin were earning higher incomes, more than a lakh per month. These migrants returned to Chennai and invested in fishing assets, boats and nets, with the support of their village kin (Mr KV, key informant).

With increasing levels of education amongst the youth, especially young men, and lack of remunerative local employment, many go overseas, a few gaining skilled jobs in shipping, but most working as labour in a range of companies. They see international migration as contributing to social status and mobility, but also a means of accumulating capital for investment in fishing assets at home (Rao and Manimohan 2020), as noted by Mr. KV. In fact, it is interesting to note that a large number of youth continue to be engaged in the fishing sector.

Boat owners from Rajakuppam in Chennai employ their village friends and kin as crew members on their boats, giving them a share from the fish catch (pangu) in addition to a wage, even helping them secure their own boats in a few years. Unlike international migration, while men may move first, they do eventually bring their wives and children too to stay in Chennai (Gmelch 1980), or if from labouring households, return to their village. In the words of a fishing labourer,

I was working as a fishing labour in Kasimedu from 1998 to 2004, going for multiday fishing in big trawler boats. As I was on sea a lot, my wife and children stayed in the village. When on shore, I used to stay with my fellow fishermen and the boat owner from our village provided us food. Once in three months I visited my family. I constructed a concrete house in Rajakuppam. After the tsunami in 2004, I bought a motorised boat and started fishing in the village itself. I earn a modest amount of Rs. 500 to Rs. 2000 daily from the fish catch.

Given the motivation to move was enhancing social status and social mobility alongside economic progress and the need to accumulate savings and wealth, the selection of a particular migration pathway was important in shaping the life-experiences of the migrants. The next section deals with another mechanism in the process of settlement and social mobility, garnering political support and internal solidarity, leading to the emergence of the vagaira.

Struggling to survive and the emergence of Vagairas

The first-generation migrants from Rajakuppam confronted a host of institutional barriers and everyday conflicts. Muniamma, 65, wife of one of the first migrants, noted:

My husband was the first to purchase a mechanized boat jointly with Mr. Subbu and Mr Chandran in 1975. But they could not get the boat registered in Chennai, hence returned to Rajakuppam. In 1977, leaving our children (3 boys and 4 girls) in the village, my husband and I along with his partners again moved to Chennai. We stayed with a family friend. The local fishermen’s association continued their opposition, but somehow with the help of friends we were able to register our boat. Without this, we could not have settled here.

Apart from these three boat owners, other migrants from the village started their careers as fishing labour in Chennai, given that the hurdles to boat ownership were immense. Local boat owners emphasized their territorial rights in not accepting migrants, except from the adjacent districts (Thiruvallur, Chengalpet and Kancheepuram), arguing that fishermen from the southern districts had their own harbours and ports. Apart from locality, caste and descent emerged as points of conflict between the migrants and the local fishers, as most of the Chennai fishers were Pattinavars, while those from Rajakuppam belonged to the numerically smaller and hierarchically subordinate Parvatharajakulam caste group. The crux of the issue was really about resource sharing — berthing space in the harbour, markets and marine resources — finding reasons for excluding those seen as ‘outsiders’ (Bavinck et al. 2015). As Mr KV noted:

In the beginning we encountered many issues on the basis of caste, nativity, class etc. In 1978, the Chennai fishers removed the winch from our boat and asked us to do hand peddling. They made us pay penalties when we went for fishing. We were always treated as outsiders. But we are basically hard workers. Owners themselves went for fishing, so income was high.

A turning point for the Rajakuppam migrants was the election of Mr. SV from Cuddalore district as a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) from 1984 to 1989. SV held a high position in the party and often invited the Rajakuppam fishers to discuss their needs and problems. Alongside local fishers, they too received what were called ‘federation boats’, and through his intervention, were made eligible for all government schemes and entitlements. Considered outsiders and therefore denied membership in existing boatowner associations, they now formed their own association and enrolled as members in Fishermen Cooperative Societies. Muniamma added, “enrolling in local fishermen societies not only enabled us to avail benefits, it provided us security. We now hold membership in Fishermen Cooperative Societies in Kasimedu as well as our native village”. While enabling them to seek redress if threatened by local owners or prevented from using the harbour, their dual membership has been important for their sense of identity. They continue to pay taxes and make voluntary contributions to their village panchayat for the organization of temples festivals. Though settled in Chennai for over 40 years, cremation and death rituals are performed in the village.

This first decade of struggle made the Rajakuppam fishers recognize the importance of political connections, but equally the strength of their family and kin-group in supporting their enterprise, directly as labour or indirectly through capital and other forms of support. We turn next to a deeper exploration of the social organizational mechanisms in practice.

Vagaira as social capital

The early migrants recognized the role of their family, their kith and kin, as a safety net, to confront the conflicts and crisis-like situations they encountered in Kasimedu, to resolve disputes (Varshney 2000) and take advantage of new opportunities (Isham 1999). As their children grew up, and their daughters married, they formalized a family support group known as ‘vagaira’ — literally a collective of members tied together through kinship and marriage.

The Vagaira group is an informal family collective, constituted over a period of time, bringing together generations for a common goal. Unlike other social organisations, it does not have a defined structure, though roles are predefined. Drawing primarily on the narrative of Muniammal, we describe here the dynamics of forming a Vagaira group as a form of bonding social capital (Gittell and Vidal 1998), and its role and significance in the social and economic mobility of Rajakuppam fishers.

My husband and I were both not educated, but he always emphasized three principles - work hard, don’t cheat and don’t lie. This helped us make honest earnings and educate our children. I got them married one by one to suitable partners from the families in our own and neighbouring villages. Initially, after marriage, my daughters stayed in Rajakuppam, but gradually, to support their social and economic development, I helped settle their families in Chennai. All my sons-in law were working abroad when they got married to my daughters. When they returned, however, they all came straight to Chennai. As parents, we helped them invest the money they had earned abroad in new mechanized boats, providing additional funds if required.

As a senior woman, Muniammal was central to this social organisation, negotiating with different members of the family their respective roles, contributions and entitlements. While initiated by her and her husband, the next level of the vagaira includes her 7 children, both sons and daughters, and their families. Brothers of both her sons-in-law and daughters-in-law constituted the third level. Over time, other relatives such as her sister’s son joined the group (Fig. 3).

This vagaira now has 13 families owning 26 boats. While two of her sons are not actively engaged in fishing, her daughters’ families all now own boats and are dependent on fisheries for their livelihood. Interestingly, while her sister’s son and son-in-laws’ brothers have joined the vagaira, she noted that “my husband’s brothers never showed any interest in joining us”. While pointing perhaps to her central role in building and strengthening the group, it is also evident that it has evolved over time, not all aspects pre-designed.

From Muniammal’s perspective, the most important function of the vagaira was to address the possible economic imbalances amongst the siblings.

Once my children were well-settled and self-sufficient, we expanded the group to include others. After my fourth daughter was well established, two of her husband’s brothers were invited to join our vagaira and supported to acquire assets. They each own one boat. The group expansion is closely linked to marriage ties. The vagaira provides its new members financial support for investing in boats and gear. When two of my second son-in-law’s brothers came to Chennai, my daughter mobilised money from her siblings for them to start the fishing business. Gradually after stabilizing their business, they repaid the amount to my daughter. But it is more than money. The group continues to provide moral support till they are self-sufficient.

Rapport and trust within the Vagaira is strong. The group members depend on each other for emergency cash and capital, technical knowledge, marketing support and conflict resolution to start and expand their business. Transparency in sharing information about their fishing assets like crafts, gear and other equipment, creates a team spirit. One of Muniammal’s sons, Murugan said:

If an engine or a gearbox on a boat is faulty, other members share their spare engine or gearbox to overcome this situation. Secondly, if a boat lands with less catch, four to five fishers from the Vagaira group come together to analyse its causes – is it due to the mistake of the driver, a damaged net or something else. They then suggest different ideas, but also provide support to fix the problem.

Marketing is another key area where the Vagaira members work collectively, sharing responsibilities to fetch a better price. Murugan continued:

One boat may bring 15 tons of fish, but as a single person, it will be hard for him to dispose of it. We divide the catch, and this helps us sell it quickly and efficiently. If there are delays in sale, there will also be losses in terms of price.

In practice, while being a member of the vagaira group, each family maintains a clear division between the domestic and productive spheres. Mainly women take family level decisions relating to education, health, savings, etc. But those relating to the purchase of boats, nets, other equipment, fixing traders and auctioneers for selling their fish, are taken collectively. With practical experience, new members learn to take informed decisions, yet the collective and the bonding social capital it reflects, plays a significant role in both sharing the burden of risk, and monitoring emergent threats and opportunities, beyond providing support during times of crisis.

The key elements that keep the group together are the strong relationships between siblings and kin, financial give and take, knowledge and asset sharing, collective decision-making and the exchange of suggestions/advisories. Despite these positive features, conflicts do arise, mostly related to finances and the number of boats owned. Women may get jealous of each other if their monetary expectations are not met. It is usually some of the older men, or women like Muniammal, who talk to the conflicting parties and help arrive at an amicable resolution. As KV noted, “my mother is an accomplisher, and she now plays the role of an advisor to many. She helps maintain a smooth growth curve by facilitating the resolution of the small ups and downs among and between the families of our Vagaira”. The other early migrants too established family groups which are doing well in Kasimedu. These groups provide hand-holding support to the Rajakuppam migrants if they wish to establish themselves in the sector.

Fishers from many parts of Tamil Nadu migrate to Chennai for fishing, but in the absence of a support system, during times of crisis or conflict, they see no option but to return to their home villages. Rajakuppam fishers, belonging to a homogenous but marginalised caste group, confronted many challenges they faced, by supporting each other through their family groups. This strong family cohesion played a key role in making them ‘successful’ settlers in Kasimedu. KV, eldest son of Muniammal, said:

We were the first to become boat owners in Chennai, and we then expanded our team by constituting a family group. None of the 44 fishing villages of Cuddalore has the system of Vagaira; it is we from Rajakuppam who created, demonstrated and sustained this model. Now amongst us, there are 6 Vagaira groups, each owning a minimum of 10 to maximum 30 boats.

Trust and a commitment to support each other through the exchange of goods, money and ideas in pursuit of their common interest is perhaps one of the most important factors driving the success and wellbeing of the Rajakuppam fishers in Kasimedu.

Social organisation and wellbeing outcomes

Wellbeing, as noted in the “Theoretical Framework” section, is multidimensional, encompassing elements of both materiality and sociality. This section sets out the perceptions of migrant households, those who have established themselves as mechanized boat owners. We draw out the concept of identity as a thread that runs through the relational and subjective components of social wellbeing.

While improvements in practical welfare and standards of living such as income, wealth, movable and immovable physical assets, environmental quality, physical health and livelihoods are the major elements of material wellbeing discussed by the migrant households, networks of support, care, social, cultural and political identities that determine the scope for personal action and influence in the community are perceived as relational wellbeing. Aspirations, trust and confidence, shared hopes, and levels of satisfaction were considered key aspects of subjective wellbeing.

Amongst the migrant settlers from Rajakuppam, a majority mechanized boat owners, 80% attributed their material prosperity to their membership in family groups. Due to their tireless efforts, the second-generation boat owners have created a strong asset base, with technical and human capabilities for the pursuit of modern fisheries. The value of each boat is about Rs.5 million. These owners, on an average, provide employment to around 10 fishing labour per boat per trip. Except for the seasonal ban period, they can access marine resources and earn a good income throughout the year. Mr KV observed that if a Vagaira member is willing to invest in a new boat, the family group could mobilise 10 million rupees in cash in a dayFootnote 2, such is their current economic standing. The family group was exporting fish to China. They own concrete houses in Kasimedu with all amenities and comforts. Their children have received higher and technical education, pursuing white-collar jobs in the fields of IT and engineering. Yet given their investments in the sector, they expect at least some of their children to maintain the business. Mr KV however spoke of the challenges confronting the next generation: the rising per unit costs of catch, global recession following the covid-19 pandemic, and rising fuel costs.

Material prosperity has transformed the social relationships encountered by the migrant settlers from one of conflict with and exploitation by local fishers, to those of respect and mutuality. Enrolling in local fishermen societies, establishing a separate boat owners association, building political affiliation and importantly formation of the vagaira groups, have all contributed to their relational wellbeing. A member of the traditional Ur panchayat commented that “their unity, willingness to help and care for each other and hard work has enabled them to become a source of energy and power in Chennai”. Both their economic security and educational attainment have led to the loosening of rigid cultural practices, enabling social mobility, through for example, entering into hypergamous, inter-caste marriages with both fishing and non-fishing castes. The marriage of a young woman from their community (Parvatharajakulam) to the Minister’s son (Pattinavar), for instance, has legitimized their social, economic and political status as an important and powerful group in their place of settlement.

The migrants also see an improvement in their social status through maintaining a link with their village, contributing collectively to the village festival, investing in infrastructure or extending support during times of emergency. While the same level of prosperity has not been achieved by the small-scale fishers in Rajakuppam or the fishing labour households in both sites, 40 years of migration, and the strong social ties it has nurtured, has nevertheless transformed the village too.

In terms of subjective wellbeing, the mechanized boat owners’ perceive their quality of life as highly satisfactory, as the primary purpose of their migration, both economic growth and social mobility, has been achieved. They are now seen at par with the dominant marine fishing Pattinavar caste; local conflicts replaced by a position of mutual respect if not dominance. At the same time their bonds with their family groups, fellow fishers and fishing labour have also become stronger. As Muniammal clarified, “wives of boat owners, especially senior women, have played a central role in building and maintaining social ties, both within the family and vis-à-vis the wider society”. Women’s social reproduction roles are often ignored in studies of gender relations and divisions of work in the fisheries sector (Dunaway 2013; Gopal et al. 2014). The experience of vagairas, explored in this paper, makes visible women’s central roles in ensuring the success of migrant fishers’ enterprise.

Conclusion

Fishing remains an important industry in the coastal villages of Cuddalore district, yet the problems created by industrial development in the region have been exacerbated by poor infrastructure, transport and marketing facilities, all constraining fisher livelihoods. Policies for fisheries development too, including the recent ‘blue growth’ agenda, with a focus on technological improvements and export promotion, have led to the need for large-scale capital investments in the marine fisheries sector. Small-scale fishers find it hard to make this transition, so end up migrating to major harbours such as Chennai that offer opportunities for work. Unlike migrant workers from other parts of the country who move due to distress, internal migration for these small-scale fishers is a route to both economic and social mobility, gaining status as fishers rather than labour. There is however scant understanding of the nature of such internal migration within marine fisheries in India, its drivers, mechanisms and wellbeing outcomes. This paper has sought to fill this gap, further exploring the factors contributing to the ‘success’ of such internal migration, both in terms of livelihood security and fulfilling social aspirations.

The migration trajectories for small-scale fishers have not been straightforward. Some Rajakuppam fishers first migrated overseas, others went overseas via Chennai, working initially as labourers, seeking to return with capital to invest in mechanized boats and gear. They encountered resistance from the local fishers to counter which they built a unique family-based social organisation, the vagaira. Trust was key, as financial transactions were involved, in addition to sharing key information on fish catch and markets, and emotional handholding during times of crises. At the same time, this internal solidarity enabled them to reach out to political leaders for support.

While migration is a complex process, embedded in unequal power relations, with outcomes uncertain, this case study provides us some lessons on how processes of internal migration can work more productively for marginalized groups, in this case, of fishers. First, the migrants never forgot their skills as ‘fishers’, so struggled to get these recognized, rather than seeking employment as ‘unskilled labour’, as most migrant workers do. Second, they focused on building strong social bonds, establishing a family group that was both loyal and trustworthy, willing to support each other in times of adversity, as a conscious mobility strategy. Rather than taking family solidarity for granted, building social capital has been an intentional process, requiring planning and risk-taking. Their steadfast commitment to both their fisher identity and sociality ultimately paid off, making for the aspirational transition from workers to boat-owners.

Over the past four decades, the migrant settlers from Rajakuppam, now owning almost one-tenth of the boats operating out of Chennai harbour, their children in higher education, have achieved both economic and social mobility. They belong to the upper classes amongst fisher families, with a high standard of living, and have broken caste barriers between themselves and the dominant Pattinavars. Theirs is a story not of exploitation, but of success, despite the many challenges they faced. Rather than looking at success and failure as binaries, we have deployed the concept of mobility to demonstrate the contextual nature of their life trajectories and their investments in social relations, especially marriage and kinship ties, as key mobility strategies. While marriage was initially a mechanism for recruiting workers who would be loyal to the boat-owners, over time there was a shift from individual to collective mobility strategies. through the sharing of resources. This enabled social recognition and political acceptance of the entire group rather than a particular individual. While boat ownership was important, social status and mutual respect became critical to their sense of ‘success’ or ‘life satisfaction’. Using a social wellbeing lens, helped us better understand the importance of attaining caste status and respectability vis-à-vis the dominant fisher community in their experience of mobilities.

What has often been overlooked in this process of mobility has been the silent though critical role of women in the growth of both the enterprise and the household unit. Women in boat owning households have withdrawn from active participation in fisheries, yet without their meticulous attention to sociality and social organization, the transformation in their lives over a generation would not have been possible. While their identities as fisher households are consolidated, and there is a general sense of wellbeing, gender relations, however, have not radically transformed. We leave a deeper gender analysis to a future paper.

Finally, while pointing to the diversity of mobilities, we do find in this instance that backed up by an intentional social support structure, migration and the openness to spatial mobility, serves as a key livelihood resource for fishers belonging to a marginal social group. Mobility here not just enables them to compensate for and overcome a range of social, economic and cultural constraints (c.f. Urry 2007), but achieve a trajectory signifying economic security and social status. Contrary to the stories of bare survival, or worse, exploitation, this paper has demonstrated the possibilities for positive wellbeing outcomes, in its varied dimensions, over time and space. We hope that this pilot study will open up space for further research on different forms of social organization and how they shape the lives and migration trajectories of coastal communities.

Notes

All names have been changed in line with ethical procedures of anonymity and confidentiality.

1 USD = 81.75 INR on 28th April 2023

References

Aswathy, P., and K. Kalpana. 2018. The ‘stigma’ of paid work: capital, state, patriarchy and women fish workers in South India. Journal of International Women's Studies 19 (5): 113–128.

Azmi, F., R. Lund, N. Rao, and R. Manimohan. 2021. Well-being and mobility of female-heads of households in a fishing village in South India. Gender, Place and Culture 28 (5): 627–648.

Bavinck, M. 2020. Implications of legal pluralism for socio-technical transition studies–scrutinizing the ascendancy of the ring seine fishery in India. The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law 52 (2): 134–153.

Bavinck, M., S. Karuppiah, and S. Jentoft. 2015. Contesting inclusiveness: the anxieties of mechanised fishers over social boundaries in Chennai, South India. The European Journal of Development Research 27 (4): 589–605.

Bodvarsson, Ö.B., N.B. Simpson, and C. Sparber. 2015. ‘Migration theory’ (Chapter 1). In Handbook of the economics of international migration, Volume 1, ed. B.R. Chiswick and P.W. Miller, 3–51. North-Holland Amsterdam. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53764-5.00001-3.

Bourdieu, P., and J.D. Wacquant. 1992. An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

CMFRI-DoF. 2020. Marine fisheries census 2016 - Tamil Nadu. Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Indian Council of Agricultural Research, Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, 308. Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry and Dairying, Government of India.

Coleman, J.S. 1988. Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120.

Cresswell, T., and P. Merriman. 2011. Geographies of mobilities: practices, spaces and subjects. London: Ashgate.

De Haan, A. 1999. Livelihoods and poverty: the role of migration – a critical review of the migration literature. The Journal of Development Studies. 36 (2): 1–47.

Devaraj, M., R. Paul Raj, E. Vivekanandan, K. Balan, R. Sathiadas, and M. Srinath. 1996. Coastal fisheries and aquaculture management in the east coast of India. Marine Fisheries Information Service Technical and Extension Series 141: 1–9.

Dunaway, W.A. 2013. Gendered commodity chains: seeing women’s work and households in global production. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Erlinghagen, M., C. Kern, and P. Stein. 2019. Internal migration, social stratification and dynamic effects on subjective well being. SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research No. 1046. DIW Berlin.

Garip, F. 2008. Social capital and migration: how do similar resources lead to divergent outcomes? Demography. 45 (3): 591–617.

Gittell, R., and A. Vidal. 1998. Community organizing: building social capital as a development strategy. Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Gmelch, G. 1980. Return migration. Annual Review of Anthropology 9 (1): 135–159.

Gopal, N., L. Edwin, and B. Meenakumari. 2014. Transformation in gender roles with changes in traditional fisheries in Kerala, India. Asian Fisheries Science Special Issue 27S: 67–78.

Granovetter, M. 1973. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78: 1360–1380.

Immanuel, J.J., and N.C. Narayanan. 2015. A brief history of Blue Revolution 2.0. Economic and Political Weekly 57 (24): 7–8.

Isham, J. 1999. The effect of social capital on technology adoption: evidence from rural Tanzania. In Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association. New York: Processed.

Islam, M.M., and J. Herbeck. 2013. Migration and translocal livelihoods of coastal small-scale fishers in Bangladesh. Journal of Development Studies 49 (6): 832–845.

Johnson, D.S., T.G. Acott, N. Stacey, and J. Urquhart, eds. 2018. Social wellbeing and the values of small-scale fisheries. Cham: Springer International.

Kozel, V., and B. Parker. 2000. Integrated approaches to poverty assessment in India. In Integrating quantitative and qualitative research in development projects, ed. Michael Bamberger. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Kusakabe, K P. Sereyvath (2020). Adapting to diminishing fish resources in Cambodia: fisheries on the shoulders of women and migrating adult children in fishing communities. Lund, R., Kusakabe, K., Rao, N., N. Weeratenge Fisherfolk in Cambodia, India and Sri Lanka: migration, gender and wellbeing. New Delhi. Routledge.

Lund, R., K. Kusakabe, N. Rao, and N. Weeratenge, eds. 2020. Fisherfolk in Cambodia, India and Sri Lanka: migration, gender and wellbeing. New Delhi: Routledge.

McKenzie, D., and H. Rapoport. 2007. Network effects and the dynamics of migration and inequality: theory and evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics 84 (1): 1–24.

Menon, Ajit, Maarten Bavinck, Tara N. Lawrence, Nitya Rao, G. Muthusankar, D. Balasubramanian, A.S. Arunkumar, Singh A. Bhagath, Babu D. Senthil, and Nicolas Bautès. 2023. Coastal transformation and fisher wellbeing: perspectives from Cuddalore District, Tamil Nadu, India. Chennai: Madras Institute of Development Studies. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7503034.

Mohanraj, G., S.J. Kizhakudan, E. Vivekanandan, H.M. Kasim, S.L. Pillai, J.K. Kizhakudan, and P. Vasu. 2012. Quantitative changes in bottom trawl landings at Kasimedu, Chennai during 1998-2007. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of India 54 (2): 46–51.

Moser, C. 1996. Confronting crisis: a comparative study of household responses to poverty and vulnerability in four poor urban communities. In Environmentally sustainable development studies and monographs Series 8. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Munshi, Kaivan, and Mark Rosenzweig. 2016. Networks and misallocation: insurance, migration, and the rural-urban wage gap. American Economic Review 106 (1): 46–98.

Narayan, D. 1995. Designing community-based development. In Social Development Paper 7. World Bank, Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Network. Washington, D.C.: Processed.

Rao, N. 2001. Enhancing women’s mobility in a forest economy: transport and gender relations in the Santal Parganas, Jharkhand. Indian. Journal of Gender Studies 8 (2).

Rao, N. 2014. Migration, mobility and changing power relations: aspirations and praxis of Bangladeshi migrants. Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 21 (7): 872–887.

Rao, N., and R. Manimohan. 2020. (Re-)Negotiating gender and class: new forms of cooperation among small-scale fishers in Tamil Nadu. In UNRISD Occasional Paper 11, 32. https://www.unrisd.org/UNRISD/website/document.nsf/(httpPublications)/8D96D7A1CEB545DB802585D1002E326E?OpenDocument. Accessed 15/7/23

Saxena, S., R. Purvaja, G.M.D. Suganya, and R. Ramesh. 2013. Coastal hazard mapping in the Cuddalore region, South India. Natural Hazards 66 (3): 1519–1536.

Sen, A. 1999. Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shelton, C. 2017. The role of culture in adaptive responses to climate and environmental change in a Fijian village. Unpublished PhD thesis. University of East Anglia. Norwich. UK

Skeldon, R. (2004). More than remittances: other aspects of the relationship between migration and development. Population Division of the United Nations. [En línea]. New York, disponible en: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publication s/thirdcoord2004/P23_AnnexIV. pdf. Accesado el día 30 de agosto de 2006

Sriganesh, J., P. Saravanan, and V.R. Mohan. 2015. Remote sensing and GIS analysis on Cuddalore Coast of Tamil Nadu. India, Journal of Advanced Research in Geo Sciences & Remote Sensing 2.

Thurston, E., and K. Rangachari. 1987. Castes and tribes of Southern India. Vol. 6. New Delhi, India: Asian Educational Services.

Urry, J. 2007. Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Vandergeest, P., and M. Marschke. 2019. Modern slavery and freedom: exploring contradictions through labour scandals in the Thai fisheries. Antipode. 52 (1): 291–315.

Vanniasinkam, N., M. Faslan, and N. Weeratunge. 2020. Seasonal migration, resource access, contestation, and conflict among fishers on the west and east coasts of Sri Lanka. In Fisherfolk in Cambodia, India and Sri Lanka: migration, gender and wellbeing, ed. R. Lund, K. Kusakabe, N. Rao, and N. Weeratenge, 58–74. New Delhi: Routledge.

Varshney, A. 2000. Ethnic conflict and civic life: Hindus and Muslims in India. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press.

Weeratunge, N., C.B. Bene, R. Siriwardene, A. Charles, D. Johnson, E.H. Allison, P.K. Nayak, and M.C. Badjeck. 2014. Small-scale fisheries through the wellbeing lens. Fish and Fisheries 15: 255–279.

White, S.C. 2008. Relational wellbeing: recentering the politics of happiness, policy and the self. Policy and Politics 45 (2): 121–136.

Woolcock, M., and D. Narayan. 2000. Social capital: implications for development theory, research, and policy. The World Bank Research Observer 15 (2): 225–249.

Acknowledgements

We thank the men and women in both the home village and the destination who gave their time to share their life stories with us. Finally, we are very grateful for the anonymous reviewers and editor of Maritime Studies for their constructive comments on the paper.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge the funding support for the project ‘Coastal transformations and fisher wellbeing’ from the Economic and Social Research Council Grant No. ES/R010404/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rao, N., Sophia, J.D. Identity, sociality and mobility: understanding internal fisher migration along India’s east coast. Maritime Studies 22, 42 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-023-00333-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-023-00333-1