Abstract

Privatized fishery management schemes, alongside other cultural and social changes, have led to a high average age in some fisheries, where youth and newcomers are not meaningfully present in the industry. This research explored the current and future opportunities and constraints for youth and newcomers in Icelandic fisheries, which are managed by an Individual Transferable Quota system. Data were collected through participant observation and 25 semi-structured interviews with key individuals in fisheries. Inductive qualitative analysis of interview data determined recurrent themes that illustrate how rural outmigration, cost, and changing social expectations have led to a decrease of youth and newcomers in Icelandic fisheries. Results show that the perception of fishers in Iceland by the general society fluctuates as the economic and cultural climate of the country changes. The ageing of the fleet in small-scale fisheries is explained by the limited access to consolidated fisheries rights, and the inability for youth to secure capital and invest in a fishery operation. Large-scale fisheries, on the other hand, have a different set of barriers for youth, such as lack of career advancement opportunities and a heavy workload. This research also documents how the absence of youth in small-scale fisheries is partially linked to a high turnover of youth in large-scale fisheries. Youth have more opportunities in large-scale fisheries, but over time, they do not receive adequate training or support to further an independent career, thereby creating a negative feedback loop leading to further reduction of recruitment in small-scale fisheries. Findings from the study support the continued call from academics and practitioners to include issues of access for newcomers in fishery management goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Market-based solutions as fishery management strategies have become common across the world through the marketization and commodification of marine resources (Garlock et al., 2022; Young et al., 2018). In commercial fisheries, privatization often takes the form of the allocation of fishing quotas to individuals, collectives, or communities (Carothers & Chambers, 2012; Olson, 2011). One common outcome of fishery privatization policies is the consolidation of quota which leads to the predictable and intended decrease of the fisheries workforce, and, at the same time, the cost of quota on the open market becomes more valuable as a limited commodity (Emery et al., 2016; Parlee & Foley, 2022; Pinkerton & Davis; 2015; Tolley & Hall-Arber, 2015; Young et al., 2018). Of note is the high average age of fishers, sometimes referred to as the “graying of the fleet,” where those individuals of the cohort who were initially allotted quota remain in the fishery, but several barriers prohibit newcomers (Coleman et al., 2019; Power et al., 2014; Ringer et al. 2018; Søvinsen, 2012; Szymkowiak et al., 2022). The combination of fisheries management changes, plus additional social factors and technological changes in the fisheries industry, can result in decreased access for newcomers in the fisheries and reduced training opportunities for youth on existing vessels (Coleman et al., 2019; Kokorsch & Benediktsson, 2018; Neis et al., 2013; Power et al., 2014; Tam et al., 2018).

The factors affecting job choice are complex, and research shows differing aspects affecting fishery recruitment around the world (Holland et al., 2020; Pollnac et al., 2012; White, 2015). In many places, the core aspects of fisheries have changed; what was once a family activity with intergenerational knowledge transmission has been replaced by capital-intensive large-scale fisheries (Karlsdóttir & Jungsberg, 2015; Neis et al., 2013; Power et al., 2014, White, 2015). Parents do not encourage the younger generations to fish (Chambers & Carothers, 2016; Power et al., 2014; Tam et al., 2018, White, 2015) and instead push them to pursue higher education to ensure economic stability in other careers (Tam, et al., 2018). For example, youth that live in current or former fishing towns in Canada recognize the importance of fisheries more than youth that live in communities with no fishing history, but they also do not believe that the fishing sector provides them with good job opportunities (Power et al., 2014). On the other hand, youth in Alaska, and in particular Indigenous youth, continue to actively push for increased access to traditional fishery livelihoods (Carothers, 2013; Ringer et al., 2018).

In Iceland, fishery privatization in the form of an Individual Transferable Quota (ITQ) system took place in the late 1980s (Chambers et al., 2017; Einarsson, 2015). Quota was sold away from small operations which in turn lead to a decrease in opportunities for work in fisheries and fish-processing plants (Chambers & Carothers, 2016; Karlsdóttir, 2008; Skaptadottir, 2000; Eythorsson, 2000). Since the 1990s, employment in fisheries has declined in Iceland; however, these changes were stronger in rural areas with a 38% decrease, compared to 27% in the capital area (Kokorsch & Benediktsson, 2018). The development and introduction of freezer trawlers meant that vessels also no longer needed to be attached to land-based operations. This caused many factories on land to become obsolete, further increasing loss of jobs not only catching fish but processing it, as well as all related livelihoods (Bjarnason & Thorlindsson, 2006) leaving many communities without other significant job opportunities.

Research has documented barriers to entry in Icelandic small-scale fisheries: small-boat fishers are on average 58 years old, and less than 5% are under 30 years old or have less than 5 years of experience (Chambers & Carothers, 2016). In 2009, the United Nations Human Rights Council deemed the Icelandic ITQ system a violation of the human right to work, according to Article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Einarsson, 2011; Symes & Phillipson, 2009). In response, the Icelandic government instituted an open small-boat jig fishery in the summer called strandveiðar (Chambers, et al., 2017; Einarsson, 2011). This and other attempts to fix the inequalities of the ITQ system, such as community quota and a long-line land-baiting concession, offer some support for fishing activities (Chambers et al., 2020). However, other societal, structural, and institutional changes have compounded the effects of the quota system, and many Icelandic rural communities continue to experience outmigration of youth who move away and do not return (Bjarnason & Thorlindsson, 2006).

As a result of conversations during participant observation (described in the “Methods” section), for this research, youth is defined as individuals who are younger than 35 years old, which is slightly older than other research that established youth as individuals younger than 30 years old (Neis et al., 2013; Power et al., 2014; Zurba & Trimble, 2014). Similarly, for the purposes of this research, a newcomer was considered as someone with less than 5 years of experience (Chambers & Carothers, 2017). Because youth are always newcomers, but newcomers are not always youth, the research also aimed to explore these different conceptualizations and how they apply to potential policy reforms. Previous research from rural communities in Iceland shows that there continues to be interest from a certain percentage of youth in partaking in fishery livelihoods (Karlsdóttir & Jungsberg, 2015; Bjarnason & Thorlindsson, 2006), and local governments continue to push for options for the renewal of the fishery workforce for youth and newcomers (Vestfjarðastofa, 2020). Although several countries around the world are addressing issues of access and aging of the fleet with policy reforms or new strategies for recruitment (Cullenberg et al., 2017; Neis et al., 2013; van Putten et al., 2012; Zurba & Trimble, 2014), there has not yet been a study specifically focused on newcomers in Icelandic fisheries. This research therefore focuses on documenting experiences and perceptions of access to fisheries from current youth and newcomers and exploring options access to fishery resources in light of growing scholarship on the social and equity aspects of sustainable fishery management (Bennett et al., 2021, Bennett et al., 2019; Crosman et al., 2022; Soliman, 2014; Österblom et al., 2020).

Methods

Scope and research ethics

Because of the relatively small population of Iceland in general and the small numbers of youth in fisheries discussed above, the major questions of this research apply to Icelandic fisheries nationwide. However, to narrow in on a manageable sub-set of potential interviewees, this research was carried mostly in the northerly Westfjords of Iceland. In later phases, interviews with fishers and related interested parties in other locations around Iceland were used to confirm or challenge the findings that came from the research in the Westfjords. The Westfjords have a rich history in fisheries, due to the proximity to important fishing grounds (Karlsson, 2006). The loss of job opportunities after introduction of the ITQ system, in addition to the financial crisis (Benediktsson & Karlsdottir, 2011), caused increased rates of youth outmigration, which in addition to the already steady decrease in the population of the Westfjords since the 1920s, impacting the resilience of these communities (Karlsdóttir & Jungsberg, 2015; Seyfrit et al., 2010). Because of project size constraints, several important aspects of fisheries are not included in this study. For example, although there was a diversity of informants regarding gender and nationality; interview questions were not tailored to explore in depth how gender and nationality affect newcomer experiences. There was not a focus on processing or other fishery-related industries (on-shore baiting, net supply and repair, aquaculture, etc.), which would have important implications for youth searching for career opportunities.

All research followed established human participants ethics protocols and the informed consent process. All participants in all stages of research were informed in advance about the aims and objectives of the research and were asked to give their consent to participate in the study. The results of the study are presented in a grouped manner and do not contain information that could direct to the identification of the interviewees.

Participant observation and semi-structured interviews

Participant observation and general observation were employed by first author Lebedef (see Lebedef, 2021) to build trust and gather knowledge and information on everyday life in fishing communities that would not be possible to obtain through formal interviews. This sort of informal data sampling, coupled with the long duration of observation, was random enough to ensure that observations were not biased. Participant observation was done throughout the whole research process, from the start of the project in May 2018, until its completion in August 2021, and involved assisting on vessels and working for a fishing company to land the catch. Being fully immersed in the research environment for 3 years makes it hard to quantify the number of participant observation and general observation activities, but on average, they occurred 2–10 times a week through the duration of the research.

Semi-structured interviews were employed to provide a deeper understanding of opinions and experiences. Potential interviewees were selected by different experiences in the fishery industry as possible and critical cases, such as families of fishers, youth who work as crew on large or small boats, businesses that employ youth and newcomers on trawlers, small boats that hire part-time crew, or other similar leaders in the fisheries industry. A total of 25 interviewees were selected from different types of fisheries, at different stages of their careers and with different backgrounds, to get the most comprehensive understanding of experiences in the fishing sector. Semi-structured interview questions focused on the interviewee’s background information such as family, early life, education, and access to financial support, as well as perceptions on fisheries, policies, and job experiences. Interviewees were also asked if they had ideas on how to make innovations in the fisheries to make them more attractive to youth or to facilitate access and opportunities for youth and newcomers.

Data analysis

Field notes from observations were recorded by hand in a field journal and later transcribed into a Word document for analysis. Recorded interviews were transcribed in Word. Transcripts were then printed and analyzed by color-coding text for recurrent sub-themes following inductive coding methods from Ryan and Bernard (2003). Sub-themes from interviews were linked into larger thematic groups (Bernard, 2006), and continued participant observation data were used to fill gaps in knowledge, confirm findings, continue to build the models, and ensure that no additional themes or information were missed inadvertently.

Closing the research loop: data validation

Finally, a series of interviews were conducted to confirm findings from participant observation and semi-structured interviews. “Closing the loop” in the research process can help to identify and define management issues from the eyes of the participant. Participatory research activities such as this also help empower communities, reinforce management, and rebuild trust between local interested parties and official bodies (Trimble & Berkes, 2013). Five key individuals were given the main findings in written format, and asked if the findings as presented matched their experiences and perceptions. Three of the five individuals had not been interviewed prior to the presentation of these results, in order to maximize the data saturation and ensure that the results were not biased, and that no new information was missed in the data collection.

Results and discussion

From the qualitative analysis of the 25 semi-structured, five validation interviews, and field notes from participant observation, five main thematic areas emerged, presented in depth in Lebedef (2021). Here, we focus on the following four themes: (1) youth exposure to fisheries, (2) aspects of entry to fisheries, (3) fishery lifepaths and careers, and (4) policy recommendations for newcomer support. Exemplar quotes are included to add in-depth meaning about the topics straight from the words of the interviewees, and results are discussed in the larger context of international research on similar topics.

Exposure to fisheries

In the past, working in fisheries was very often the only career opportunity available to youth in rural communities, whether it was working on a fishing boat or processing the fish on land in factories. Minimal regulations allowed youth to be exposed and start working in the fisheries as young teenagers, or sometimes even earlier. As one informant noted:

“You know, all the kids went to the shrimp factory in the summertime or sometimes on weekends, if sometimes the factory needed. So, this was kids 13 and up at least. And you know, I always worked in fish and sea related [trades] when I was a kid, when I was in high school.”

Through a combination of technological, economic, and social changes as reviewed above, the fishing industry employed fewer people overall and became less visible in daily life. In many ways, fishing activities have simply moved somewhere else, as evidenced in several interviews where informants noted that a considerable number of youth with fishery career dreams move from smaller communities to larger towns, or commute in between vessel tours. This causes a negative feedback loop for recruitment; while the youth have followed their career dreams of being engaged in fisheries, the physical presence of the vessel and support industries in communities is lacking. Because recruitment is partially linked to exposure to fishing (see Ringer et al., 2018 for more examples of negative exposure feedback loops), it follows that youth would not see viable career options in an industry which is not meaningfully present.

However, although overall exposure to fisheries has declined, there is a paradox where the identity of fisheries and coastal communities remains strong and ever-present for some individuals. The obvious family connection to fisheries was a strong thread in all interviews. Having family in fisheries means having already been exposed to the industry, and exposure becomes experience. Most interviewees got a job on board thanks to a relative that recommended them to the captain. In addition, where someone was born and grew up is important; individuals that come from fishing communities may find a job in fisheries more easily than someone that comes from a town that has no active fisheries. As several interviewees explained, most of the fish is landed in the greater Reykjavík area, mainly by the big fishing companies with large trawlers, but because the Reykjavík area is big and the economy so diverse, the fishing industry is not what a young person growing up in the capital area sees the most in their everyday life. One young interviewee explained:

“Ja, I lived in Reykjavik, for more than 10 years. But I think it’s always kind of… in Reykjavik they don’t know what [fisheries are]… I think I always got a like ‘that’s cool’ [when I told people I worked in fisheries]…. Not knowing really why [fisheries are cool] or how… and they probably just see all the cliches put together. Even though the cliches are good for fishermen, you know, they sound cool, they sound great, you are a ‘hero of the sea’, you are a ‘strong man’ and it’s all those things. So I think in Reykjavík they know less, but they still don’t disrespect or don’t look down on it; because they don’t really know what it is…”

In this quote, the paradox of exposure is illustrated. Because of consolidation, fisheries moved to the capital area, but at the same time, because it is a larger city, fisheries still do not remain visible in everyday life for residents of the capital area. In fact, throughout this study, a major theme emerged about location and identity of fisheries in Iceland. In Iceland, the decrease in exposure to fisheries appears to be also linked to decrease in the interest to pursue fisheries. Informants noted than in the communities where fishing is still a prevalent economic activity, exposure and therefore possible recruitment or positive perception of fisheries are greater than in communities where fisheries are not as prevalent or visible.

Societal perceptions of fisheries

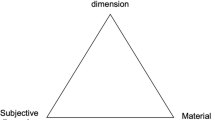

The decrease in fishery exposure also seems to have an impact on the perception of the general society towards the fishing sector. For many people, fishing is an activity belonging to the past that has been glamorized and romanticized. These perceptions are linked with the way fishers are described and add to the factors that pull youth into fisheries or push them away. One interviewee noted that parents often talk negatively about fisheries and push their children into other job paths. The mechanisms behind changes in Icelandic society is beyond the scope of this research; however, it is evident that values stemming from work in the primary industries of farming and fishing (Magnússon, 1989) still play a role in the interviewees’ perceptions of self, value, and future related to fisheries. Interviewees suggested that younger generations are pushed to follow what are perceived to be more noble or prestigious pathways, and fisheries is quite often viewed as a remnant of the past. Through interviews and participant observation, the most common descriptors of “fishers in the past” compared to “fishers these days” showed the common perceptions of negative qualities of current fishers (Fig. 1). For example, the common idea that fishers are often un-educated goes deeper into the perception that they have no agency in their lives, and fisheries are a last resort for employment. However, for other informants, the feeling about the “un-educated” aspect would be more neutral or even positive, as individuals would comment that for a job that does not require higher education, the salary from fisheries is very good, and it is an honorable job that allows for independence from the general push in society of formal education that leads to office jobs.

An interesting caveat to the trends of public perceptions of fisheries is that the public’s image of fisheries appears to fluctuate depending on the political and economic climate of the country. Various large events in the history of modern Iceland have related to fisheries, such as independence from Denmark in 1944, the Cod Wars in the 1970s, the introduction of the quota system in the 1980s, the banking crisis of 2008, and most recently the Covid-19 pandemic. Throughout these various events, the economic climate had an impact on the value of the Icelandic currency which directly impacts fisheries. As one interviewee said “if the krona is weak... we're on the other side of society. When the people who live here […] have it good, then we have it shitty. It's pretty weird.” This feeling is evidenced through experiences after the 2008 economic crisis (Benediktsson & Karlsdottir, 2011) and is echoed by another interviewee, who explained how, pre-2008, “everybody wanted to come out at sea because there was so much good money in it. Now not so much.”

As the value of fishing fluctuates, so does the value of the fishers in society’s eyes. When fishers are doing well, they are criticized and told that they get too much money from the nation’s commonly held natural resources. As recalled by an interviewee, when fishers went on strike in 2016, the “media turned on them,” because, as he explained, the media is influenced by the big fishing companies, the owners of the boats. The interviewee felt that the media portrayed the fishermen in a way that made it so that the public did not back the strike. On the reverse angle, more recently, there were incidents of Covid-19 outbreaks onboard fishing vessels leading to very visible public discourse describing fishers as modern-day slaves and questioning the working conditions of crew at sea.

New entry in fisheries

Although there is a common belief regarding fisheries that, as worded by one interviewee, “Everybody is allowed to be a fisherman. Doesn’t matter who you are,” it is also clear that there are certain factors that influence access to fisheries. The relationship between these factors is complex for newcomers as well as for established fishers, but several important aspects emerged through the research process. Many interviewees discussed that an important factor determining whether a person will pursue a career in fisheries is the individual’s personality, as one interviews said, “You can almost see when you leave the harbor who has what it takes and who doesn’t.” Interviewees explained how in many instances, if a potential new crewmember had no prior experience on board of a fishing vessel but was known to be a hard worker on land-based jobs, they were likely to be given a chance to try out a few tours on a vessel. Eagerness to work hard and to learn will also help the newcomers to climb the career ladder, as interviewees noted that there are not many or even any seminars that will teach the skills of the trade that could help newcomers get a better position on the boat hierarchy and shares.

Around the world, fishing is an occupation deeply embedded in experiential knowledge and learning by doing. Although there is an understandable push for formal education and training, most interviewees agreed that there is a considerable amount of fisher’s knowledge that cannot be learned in books but only comes through practice and experience and that “some people never get it.” In terms of official training, everyone working at sea must complete the safety at sea class, which needs to be renewed every 5 years. Newcomers have a special exemption, with which they can be out at sea for 170 h, allowing new people to try fishing first before committing. Depending on the company or the captain of the boat, the cost of the renewal of the safety certificate may be covered by the fishing company, although this is not necessarily common practice. On large-scale trawlers, the next level after a general deckhand is the net specialist, responsible for opening and closing the nets when fishing and mending any rips. The only way to learn how to mend nets is to go to seminars on land or ask someone to teach you on board of the ship. However, the obstacles that individuals face when deciding whether to learn this skill can dissuade them from ever trying, as individuals most often need to learn on their own free time. The highest position without formal education is the shift manager, or as one interviewee put it, the “highest of the lows.”

Special schooling exists for engineers and other trades needed specifically onboard large vessels, and there is additional schooling for larger vessels, passenger vessels, and coast guard ships. A positive aspect of this schooling process is that students are not required to attend all classes in person; they can do distance learning and then attend the class physically occasionally. The reasoning behind this is that individuals can study for the captain licenses without having to stop working or having to move to Reykjavik, where the school is located. However, completing education does not guarantee a higher spot on the hierarchy of a fishing vessel. One must be a general crew member for 2 years before advancing, and even changing from one fishing vessel to another one, in a different town or company, might mean having to start the “ladder” from the beginning.

A major aspect of fisheries addressed by many informants as a barrier to newcomers is bookkeeping. One interviewee explained how his mother oversaw all his finances, and without her, he would probably be lost. Being able to understand how salary and finances work is of major importance when owning a fishery company, especially when owning one’s own small boat. Crew on large-scale boats does not need to think about repair costs, oil price, and quota costs. Most of the younger informants agreed that money management was an acquired skill that was mostly taught through personal connections rather than in training, but financial training was something that could be easily updated in the formalized schooling programs.

Access rights for small companies

For those striving to own their own fishing business, the cost of schooling, good boats, gear, and so on are all necessary, but in the eyes of the informants, the largest barrier was access to the right to fish. On this topic, several interviewees talked about how in other countries access to quota was facilitated for people who wanted to become independent fishers, for example, the Norwegian youth lottery system (Søvinsen, 2012). Most of the interviewees described how the quota system was the main barrier and how impossible it was to hold any quota, because it is so expensive and consolidated in larger companies. The next best option is to rent quota, although the general feeling about renting quota was also that the price is too high.

If neither buying nor renting quota is feasible, then the only fishery an individual can enter is the summer cod jig fishery called strandveiðar. The profit made from the strandveiðar fishing season is often not enough for an individual to live off for a whole year without one or more additional seasonal jobs in the wintertime. The opinions about strandveiðar seemed to fluctuate depending on the interviewee’s financial situation. Those who were financially stable and could afford to buy a boat and participate in strandveiðar viewed this system positively, while those who relied on strandveiðar as means to make ends meet expressed their frustration at how this was not a solution to the issues of privatization of fisheries and the obstacles to acquiring quota. Furthermore, as has been shown in previous research, the goals of strandveiðar are unclear (Chambers et al., 2017). There are individuals in the system that sold quota and now fish solely in the strandveiðar system. These individuals would count as newcomers in the specific system, but not to fisheries overall. Furthermore, the cost of a boat and gear can be prohibitive for young entrants without much savings. The difference here between access for youth and/or newcomers highlights the importance of definitions in fishery polices in general, and clear and measurable goals for any future policies supporting youth and/or newcomers.

Important to this discussion is also the difference between fishery types. Strandveiðar supports independent owner-operator newcomers, since strandveiðar is by-and-large carried out with only one person on board. Outside of strandveiðar, there is also a community quota system which can support independent fishers and smaller companies. The general feeling from the interviewees about the community quota system was that it is good because it can support fisheries, but that it tends to go to already well-established fishery companies. Furthermore, the few that decide to pursue owning their own small boat operation with little capital need to find ways to finance their expenses through the means of bank loans or shareholders. Most banks do not want to loan out money to individuals to buy boats and quota; therefore, fishers that want to have their own independent company often must resort to private loans from relatives or find investors.

Fishing lifepaths—entry/exit and horizontal/vertical movement

Youth and newcomer recruitment in fisheries around the world may not be affected the same way in small-boat fisheries as in large-boat fisheries. In Iceland, large-boat fisheries appear to have more opportunities for newcomers. In many ways, larger boats are the easier path for youth or newcomers to start working in fisheries as they do not need to buy their own gear or access rights. After entry however, vertical movement, or upward mobility, within this type of fishery can be difficult as it requires specialized training as well as an initiative to take on more responsibilities. Horizontal movement, or going between large and small fishery systems, introduces the aspects of different cultural connotations of the lifepaths in fisheries: does one start on small boats and work their way up to larger boats, or work on large vessels and “retire” to smaller vessels? Should fisheries be a year-round occupation, or is it better to be combined with other income? Answers to these questions vary by country, region, and even within families, but are important in considering the design of fishery management schemes and measurable goals.

The interviewees highlighted the various incentives for individuals to move horizontally or vertically in fisheries, i.e., climbing the hierarchy of a boat, exiting the fishery, or changing from large scale to small scale and vice versa. The quote below summarizes particularly the way salary plays a role in the decision-making processes that each individual makes when considering a career in fisheries:

“And now he has like a big house where he lives, he owns it, and he has a beautiful car and has like two snowmobiles and has family and children. He just decided to be a fisherman. And you know he could actually stop now and decide to start studying something and he would have the best ground under him so there are lots of people that see… like people learn for 10 years to become a lawyer to get a certain salary. Or you could go out in the ocean at 16 and get that salary until then, and then decide what you want to do with your life then. That’s the thing.”

Horizontal movement is limited due to the small number of small-scale boats left in Iceland. Interviewees discussed the differences in opportunities in large and small scale, as one expressed:

“There is no competition between some guys fishing maybe 3 tonnes per month on a small boat and a giant boat fishing about 1000 tonnes a month. [...but it looks like there is competition] because of the quota system, how it’s built up.”

With continual economic diversification, working in fisheries can also be a steppingstone for many youth to achieve different goals outside of fisheries, rather than an investment in a future career. Informants noted that many youth make the calculated decision to partake in a fishery with a planned early exit. Fishing for a larger company can be a quick way to make money that will cover costs of higher education and housing. This high turnover and constant flow of newcomers has interesting implications for company operations and also for fishery management. A general feeling from the interviewees was that becoming a fisher today is a choice rather than an inevitable fate for youth in coastal communities and that many are in it for the money. Interviewees noted that those who chose fisheries over higher education have no debts and can afford everything they want as well as meet their family’s needs: “Look at me now, I didn’t go to school, I’m not being proud of that, but I don’t owe anything[to the banks].”

Not being able to move vertically in a company or horizontally between fisheries can force participants to retire early from the sector (see Szymkowiak et al., 2022 for examples from Alaska). As an interviewee explained, for a fisher working on a large boat, the salary is enough to cover the expenses of buying a good small boat, but quota is almost impossible to buy. Therefore, because of the quota system, youth have more opportunities in large-scale fisheries, but, over time, do not receive adequate training or support to further an independent career, thereby creating a negative feedback loop leading to even further reduced recruitment in small-scale fisheries (Fig. 2). So, it could be said that there is a high average age in small-scale fisheries, caused by the limited access to fishing rights and the inability for youth to secure capital and invest into fishing operations; however, in large-scale fisheries, there is instead a high turnover of youth, with individuals exiting after a short time.

Feedback loops in Icelandic fisheries. After first barriers to entry, there are secondary barriers that limit job satisfaction and growth in a fishing career, creating an early or forced exit. The experience of the “forced” exit also deters future recruits to the industry, creating a negative feedback cycle; however, early exits can also be by design, where the individual never intended to establish a long-term career in fisheries

Newcomer support options

Several future options emerged from the results of the participant observation and interviews. First, the idea of a community-owned, youth fishing cooperative came up from several informants when discussing how to make such an innovation attractive both for the community and individual fishers. The cooperative would help youth enter small-scale fisheries, while being mentored by experienced fishermen. The cooperative would hold quota and own the boats which would be leased to recruits or allow new recruits to work onboard, thereby minimizing the risks associated with investing personal capital into gear and fishing rights.

Informants were very aware of similar community efforts in Norway and Alaska to increase access to fisheries. In Norway, the government has tried to increase recruitment through programs that facilitate the access of fisheries to youth, but even so, it is difficult for young fishers to move to high positions and eventually own their own companies (Søvinsen, 2012). Norway has also attempted to mitigate the effects of the quota system on youth recruitment by opening summer fisheries for youth and by establishing a youth recruitment quota (Søvisen, 2012; Neis et al., 2013). In Alaska, various policies have been implemented that aim to address economic barriers, with loan programs such as the Alaska Commercial Fishing Loan Program, the CFAB (Commercial Fishing and Agriculture Bank) Participation Loan, and the CFAB Vessel Operation Loan Over Time, which grant applicants with government and privately funded loans aimed to help fishers to buy gear and/or fishing rights (Cullenberg et al., 2017).

To strengthen recruitment, interviewees expressed the need to increase exposure and training opportunities starting from a younger age. Interviewees expressed the need for opportunities to experience fisheries starting in primary school, when youth start to think about what their interests are and what career they would like to pursue. As most interviewees explained, learning by doing rather than by reading is one important aspect in fisheries, and at the primary school level, this could be an important inspiration for children in a controlled manner. This has interesting comparisons with programs in Alaska that aim to strengthen the positive feedback loop in fishery recruitment, with exposure and training programs such as the Limited Entry Educational Permits that have both classroom and at-sea components, allowing students to work on a vessel for a season, gathering knowledge in fisheries, while also providing family and local facilities with the product of their harvest. These programs aim to involve and support young fishers through policy and decision-making processes, in addition to mentorship and training on the factors associated with owning a fishing operation such as business and risk management, as well as environmental education to better understand the science behind the policies (Coleman, et al., 2019; Cullenberg et al., 2017; Donkersloot & Carothers, 2016; Donkersloot et al., 2020).

Furthermore, infrastructure development such as harbor expansions and retrofitted abandoned facilities were thought to give a significant boost to rural communities, which would in turn support newcomers in fisheries, creating jobs and positive exposure loops. Many historical fishing communities already have significant infrastructures that are unused, and attracting fisheries to these areas could mean resuming activities and boosting employment. Support for innovation and value-added companies were also thought to further encourage the positive feedback loop, where careers in fisheries should be celebrated as not only the capture sector, but other innovative companies that rely on raw materials from capture fisheries and aquaculture.

Finally, many interviewees also noted that larger companies should take the initiative to cover the costs of some training as common practice rather than exceptions, especially for basic courses. Many thought that companies should also take the responsibility for the economic losses and the physical and mental labor that seasoned fishers’ experience when having to train newcomers on board. If the company has a high turnover, the hidden costs of training newcomers should not fall onto existing crew.

Conclusion: beyond simplified narratives of fishery systems

This research has documented that systematic obstacles have led to misconceptions of the will or intentions of youth and newcomers to be involved in fisheries. A negative exposure loop means that youth do not see viable options to be engaged in fisheries, even if the will exists. During the course of the research, several informants expressed the concern that this study was going to romanticize fisheries—telling stories of idyllic fishing communities as agentless victims harmed by external forces. Such narratives have been shaping decision-making in fisheries and come from many angles. Neo-liberal theories of human behavior also form the narrative of the greedy fisherman, which oversimplifies a complex system (Carothers & Chambers 2012; Ringer et al. 2018; Young et al., 2018). Romanticization of the fisheries means portraying fisheries as something that is ideal, which takes out the complexity and diversity of human systems. There is nothing romantic or ideal about fisheries in the past, where there was overfishing and dangerous working conditions; there is similarly nothing romantic or ideal about Icelandic fisheries in the present, where many aspiring fishers find it difficult to make career advancement move in a culturally important livelihood. Informants agreed that not everyone could be in fisheries, and they similarly did not want to look towards the past, rather they look towards the future of a modern fishery system with space for the next generation of fishers, benefit sharing of resource rent created in the fishing industries, and equitable access to Iceland’s commonly held marine resources.

Fisheries remain an important economic and cultural activity in coastal communities around the world, and as such, it may not be appropriate to consider fisheries as having a 1:1 replacement value in the work force. There are practical concerns for the connection between fishery management and the future of coastal communities, as outmigration of youth is shown to be an indicator of future population decline (Bjarnason & Thorlindsson, 2006; Ounanian, 2019) which can further threaten the resilience of rural communities (Kokorsch & Benediktsson, 2018). Care should be taken not to over-simplify the linkages between assumed inevitable trends in globalized processes and national policies that lead to rural depopulation. As other research has shown, by maintaining jobs and opportunities especially in rural communities closest to the fishing grounds, there is a strengthening and diversification of sustainable local economies which can aid in future development efforts (Drakopulos & Poe, 2023; Haugen et al., 2021).

Although there are a variety of non-fishery livelihood options available for youth and a general decrease in primary industry employment, this research has shown that there are obvious economic and cultural benefits in supporting youth and newcomers in both large- and small-scale fisheries. Important questions for decision-makers in Iceland remain. How exactly does the value of fisheries for community development play out in a changing economy? What options exist for skilled trade jobs when fisheries are not available? How do we manage and/or prioritize for the range of individuals involved in fisheries (different ages, nationalities, genders, educational backgrounds, lifepath goals, etc.)? The advances in scholarship of sustainable natural resource management call for the need to move beyond the rhetoric of natural resource management as a zero-sum game (Bennett et al., 2021; Berkes, 2009; Crosman et al., 2022; Engen, 2021; Garlock et al., 2022; Hadjimichael, 2018; Ostrom 2009; Oostdijk & Carpenter, 2022; Ovitz & Johnson, 2019; Österblom et al., 2020). If designed with specific and diverse goals in mind, fishery management systems could contain measures that address consolidation of quota, access for youth and newcomers, and support for the next generation of fishers and fishing communities in both large and small fishery systems.

References

Benediktsson, K., and A. Karlsdottir. 2011. Iceland: crisis and regional development—thanks for all the fish? European Urban and Regional Studies 18 (2): 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776411402282.

Bennett, N.J., J. Blythe, A.M. Cisneros-Montemayor, G.G. Singh, and U.R. Sumaila. 2019. Just transformations to sustainability. Sustainability 11 (14): 3881. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143881.

Bennett, N.J., J. Blythe, C.S. White, and C. Campero. 2021. Blue growth and blue justice: ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Marine policy 125: 104387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104387.

Berkes, F. 2009. Evolution of co-management: role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management 90: 1692–1702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.12.001.

Bernard, H.R. 2006. Research Methods in Anthropology: qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 4th ed. Oxford: AltaMira Press.

Bjarnason, T., and T. Thorlindsson. 2006. Should I stay or should I go? Migration expectations among youth in Icelandic fishing and farming communities. Journal of Rural Studies 22: 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.09.004.

Carothers, C. 2013. A survey of US halibut IFQ holders: market participation, attitudes, and impacts. Marine Policy 38: 515–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2012.08.007.

Carothers, C., and C. Chambers. 2012. Fisheries privatization and the remaking of fishery systems. Environment and Society: Advances in Research 3: 39–59. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2012.030104.

Chambers, C., and C. Carothers. 2016. Thirty years after privatization: a survey of icelandic small-boat fishermen. Marine Policy 80: 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.02.026.

Chambers, C., N. Einarsson, and A. Karlsdóttir. 2020. Small-scale fisheries in Iceland: Local voices and global complexities. In Small Scale Fisheries in Europe, ed. C. Pita, J. Pascuel, and M. Bavinck. Amsterdam: Springer.

Chambers, C., G. Helgadóttir, and C. Carothers. 2017. “Little kings”: community, change and conflict in Icelandic fisheries. Maritime Studies 16 (1): 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40152-017-0064-6.

Coleman, J., C. Carothers, R. Donkersloot, D. Ringer, P. Cullenberg, and B. Alexandra. 2019. Alaska’s next generation of potential fishermen: a survey of youth attitudes towards fishing and community in Bristol Bay and the Kodiak Archipelago. Maritime Studies 18: 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-018-0109-5.

Crosman, K.M., E.H. Allison, Y. Ota, et al. 2022. Social equity is key to sustainable ocean governance. npj Ocean Sustain 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-022-00001-7.

Cullenberg, P., Donkersloot, R., Carothers, C., Coleman, J., & Ringer, D. (2017). Turning the Tide: how can Alaska address the “graying of the fleet” and loss of rural fisheries access? http://fishermen.alaska.edu/turning-the-tide. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Drakopulos, L., and M. Poe. 2023. Facing change: individual and institutional adaptation pathways in West Coast fishing communities. Marine Policy 147: 105363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105363.

Donkersloot, R., and C. Carothers. 2016. The graying of the Alaskan fishing fleet. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 58 (3): 30–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2016.1162011.

Donkersloot, R., J. Coleman, C. Carothers, D. Ringer, and P. Cullenberg. 2020. Kin, Community, and diverse rural economies: rethinking resource governance for Alaska rural fisheries. Marine Policy 117: 103966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103966.

Einarsson, N. 2011. Fisheries governance and social discourse in post-crisis iceland: responses to the UN Human Rights Committee’s views in case 1306/2004. The Yearbook of Polar Law Online 3 (1): 479–515. https://doi.org/10.1163/22116427-91000068.

Einarsson, N. 2015. Marine governance, fishing and property rights in light of the constitutional debate in Iceland. Vol. 91-98. Polar Law and Resources. https://doi.org/10.6027/TN2015-533.

Emery, T.J., C. Gardner, K. Hartmann, and I. Cartwright. 2016. The role of government and industry in resolving assignment problems in fisheries with individual transferable quotas. Marine Policy 73: 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.07.028.

Engen, S., V.H. Hausner, G.G. Gurney, E.G. Broderstad, R. Keller, A.K. Lundberg, et al. 2021. Blue justice: a survey for eliciting perceptions of environmental justice among coastal planners’ and small-scale fishers in Northern-Norway. PLoS ONE 16 (5): e0251467. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251467.

Eythorsson, E. 2000. A decade of ITQ-management in Icelandic fisheries: consolidation without consensus. Marine Policy 24: 438–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-597X(00)00021-X.

Garlock, T., J.L. Anderson, F. Asche, M.D. Smith, E. Camp, J. Chu, K. Lorenzen, and S. Vannuccini. 2022. Global insights on managing fishery systems for the three pillars of sustainability. Fish and Fisheries 23: 899–909. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12660.

Hadjimichael, M. 2018. A call for a blue degrowth: unravelling the European Union's fisheries and maritime policies. Marine Policy 94: 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.05.007.

Haugen, B.I., L.A. Cramer, G.H. Waldbusser, and F.D.L. Conway. 2021. Resilience and adaptive capacity of Oregon’s fishing community: cumulative impacts of climate change and the graying of the fleet. Marine Policy 126: 104424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104424.

Holland, D.S., J.K. Abbott, and K.E. Norman. 2020. Fishing to live or living to fish: job satisfaction and identity of west coast fishermen. Ambio 49: 628–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01206-w.

Karlsdóttir, A. 2008. Not Sure about the Shore! Transformation effects of individual transferrable quotas on Iceland's fishing economy and communities. Enclosing the Fisheries: People Places and Power 68: 99–117.

Karlsdóttir, A. & Jungsberg, L.,. (2015). Nordic Arctic Youth Future Perspectives, Nordregio Working Paper 2015:2 Stockholm. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:843858/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Karlsson, G. 2006. A Brief History of Iceland. Edda Uk.

Kokorsch, M., and K. Benediktsson. 2018. Prosper or perish? The development of Icelandic fishing villages after the privatisation of fishing rights. Maritime Studies 17 (1): 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-018-0089-5.

Lebedef, E. 2021. Youth and newcomers in Icelandic Fisheries. MRM (Master of Resource Management) thesis. University Centre of the Westfjords.

Magnússon, F. 1989. Work and the identity of the poor: work load, work discipline, and self-respect. In The Anthropology of Iceland, ed. E. Durrenberg and G. Pálsson, 140–156. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt20fw942.

Neis, B., S. Gerrard, and N.G. Power. 2013. Women and children first: the gendered and generational socialecology of smaller-scale fisheries in Newfoundland and Labrador and Northern Norway. Ecology and Society 18 (4): 13. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06010-180464.

Olson, J. 2011. Understanding and contextualizing social impacts from the privatization of fisheries: an overview. Ocean and Coastal Management 54: 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.02.002.

Oostdijk, M., and G. Carpenter. 2022. Which attributes of fishing opportunities are linked to sustainable fishing? Fish and Fisheries 23: 1469–1484. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12706.

Ostrom, E. 2009. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 325 (5940): 419. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1172133.

Ounanian, K. 2019. Existential fisheries dependence: remaining on the map through fishing. Sociologia Ruralis 59 (4): 810–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12248.

Österblom, H., C.C. Wabnitz, and D. Tladi. 2020. Towards Ocean Equity. Washington, DC: World Resource Institute. https://oceanpanel.org/publication/towards-ocean-equity/. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Ovitz, K.L., and T.R. Johnson. 2019. Seeking sustainability: employing Ostrom’s SESF to explore spatial fit in Maine’s sea urchin fishery. International Journal of the Commons 13 (1): 276–302. https://doi.org/10.18352/ijc.866.

Parlee, C., and P. Foley. 2022. Neo-liberal or not? Creeping enclosures and openings in the making of fisheries governance. Maritime Studies 21: 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-021-00255-w.

Pinkerton, E., and R. Davis. 2015. Neoliberalism and the politics of enclosure in North American small-scale fisheries. Marine Policy 61: 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.025.

Pollnac, R., M. Bavinick, and I. Monnereau. 2012. Job satisfaction in fisheries compared. Social Indicators Research 109: 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0059-z.

Power, N.G., M.E. Norman, and K. Dupré. 2014. “The fishery went away”: the impacts of long-term fishery closures on young people's experience and perception of fisheries employment in Newfoundland coastal communities. Ecology and Society 19 (3): na. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06693-190306.

Ringer, D., C. Carothers, R. Donkersloot, J. Coleman, and P. Cullenberg. 2018. For generations to come? The privatization paradigm and shifting social baselines in Kodiak, Alaska's commercial fisheries. Marine Policy 98: 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.09.009.

Ryan, G.W., and H.R. Bernard. 2003. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 15: 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569.

Seyfrit, C.L., T. Bjarnason, and K. Olafsson. 2010. Migration intentions of rural youth in iceland: can a large-scale development project stem the tide of out-migration? Society & Natural Resources: An International Journal 23 (12): 1201–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920903278152.

Skaptadottir, U.D. 2000. Women coping with change in an Icelandic fishing community: a case study. Women's Studies International Forum 23 (3): 311–321.

Soliman, A. 2014. Using individual transferable quotas (ITQs) to achieve social policy objectives: a proposed intervention. Marine Policy 45: 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.11.021.

Søvinsen, S.A. 2012. The recruitment paradox: recruitment to the Norwegian fishing fleet. In Fishing People of the North: Cultures, Economies, and Management Responding to Change, vol. 97-116. Anchorage, Alaska: Alaska Sea Grant, University of Alaska Fairbanks. https://doi.org/10.4027/fpncemrc.2012.09.

Symes, D., and J. Phillipson. 2009. Whatever became of social objective in fisheries policy? Fisheries Research 95: 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2008.08.001.

Szymkowiak, M., A. Steinkruger, M. Melissa Rhodes-Reese, and D.K. Lew. 2022. Upward mobility in Alaska fisheries: a case study of permit acquisition for crewmembers. Ocean & Coastal Management 228: 106327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106327.

Tam, J., K. Chan, T. Satterfield, G. Singh, and S. Gelcich. 2018. Gone fishing? Intergenerational cultural shifts can undermine common property co-managed fisheries. Marine Policy 90: 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.01.025.

Tolley, B., and M. Hall-Arber. 2015. Tipping the scale away from privatization and toward community-based fisheries: policy and market alternatives in New England. Marine Policy 61: 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2014.11.010.

Trimble, M., and F. Berkes. 2013. Participatory research towards co-management: lessons from artisanal fisheries in coastal Uruguay. Journal of Environmental Management 128: 768–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.06.032.

van Putten, I.E., E. Quillérou, and O. Guyader. 2012. How constrained? Entry into the French Atlantic fishery through second-hand vessel purchase. Ocean & Coastal Management 69: 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.07.023.

Vestfjarðastofa. (2020). Áfram Árneshreppur! Retrieved from Vestfirðir.is: https://www.vestfirdir.is/is/verkefni/aframarneshreppur. Accessed 15 May 2023.

White, C.S. 2015. Getting into fishing: recruitment and social resilience in North Norfolk's 'Cromer Crab' Fishery, UK. Sociologia Ruralis 55: 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12101.

Young, O.R., D.G. Webster, M.E. Cox, J. Raakjær, L.Ø. Blaxekjær, N. Einarsson, and R.S. Wilson. 2018. Moving beyond panaceas in fisheries governance. PNAS 115 (37): 9065–9073. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1716545115.

Zurba, M., and M. Trimble. 2014. Youth as the inheritors of collaboration: crises and factors that influence participation of the next generation in natural resource management. Environmental Science & Policy 42: 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.05.009.

Acknowledgements

The authors are immensely grateful for the time and patience of the interviewees who took part in this research. We thank Níels Einarsson and Unnur Dís Skaptadóttir for comments on earlier versions of the work which greatly improved the manuscript.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 869327, “Toward Just, Ethical and Sustainable Arctic Economies, Environments and Societies (JUSTNORTH).”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, CC; methodology, CC and EL; data collection, EL; data analysis, EL; draft preparation, EL and CC; review and editing, CC; funding acquisition, CC. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lebedef, E.A., Chambers, C. Youth and newcomers in Icelandic fisheries: opportunities and obstacles. Maritime Studies 22, 34 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-023-00326-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-023-00326-0