Abstract

Purpose of Review

The purpose of this review is to summarize some of the recent research studies on healthcare disparities across various subspecialties within otolaryngology. This review also highlights the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on disparities and proposes potential interventions to mitigate disparities.

Recent Findings

Significant healthcare disparities in care and treatment outcomes have been reported across all areas of otolaryngology. Notable differences in survival, disease recurrence, and overall mortality have been noted based on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), insurance status, etc. This is most well-researched in head and neck cancer (HNC) within otolaryngology.

Summary

Healthcare disparities have been identified by numerous research studies within otolaryngology for many vulnerable groups that include racial and ethnic minority groups, low-income populations, and individuals from rural areas among many others. These populations continue to experience suboptimal access to timely, quality otolaryngologic care that exacerbate disparities in health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health and healthcare disparities are pervasive in the USA and globally, leading to preventable morbidity and mortality. Importantly, these disparities are modifiable and therefore demand our urgent attention. Healthcare disparitiesare differences in access to healthcare for members of different groups that contribute to inequities in health outcomes [1]. This is distinct from health disparitiesthat refer to differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and overall disease burden among specific groups [2]. Innumerable studies have documented healthcare disparities in the USA based on patient race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status (SES), insurance status, education level, language, gender, sexual orientation, and geographic location among many others [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. “Social Determinants of Health (SDH)” are defined as the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, learn, and age that shape their daily life. SDH can be grouped into five domains: access to education, access to healthcare, financial stability, neighborhood, and community [10]. These factors are interconnected and collectively form the socioecological framework as shown in Fig. 1.

Research on healthcare disparities focuses on detecting, understanding, and ameliorating disparities [11, 12]. However, most of the research to date in otolaryngology has been on detecting disparities (showing that they exist) with a growing literature based on understanding mechanisms [11, 12]. Implementation research, trials, and health policy interventions are greatly needed within our field. This review article focuses on healthcare disparities in otolaryngology, including only recent and high impact articles despite the abundance of epidemiological literature in the setting of increased national focus on health disparities since 2020.

Disparities in Access to Healthcare

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement defines “access” as timely patient care in the right location with the right clinical team [13]. Disparities in access to care often underlie health inequities.

The “Voltage Drop” Framework of Access to Care

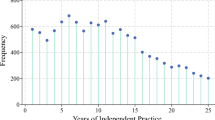

A “voltage drop” framework [14] can be used to show how patients may face multiple “resistance points” along the continuum of surgical care, as shown in Fig. 2 [15]. Patients may face barriers to initial presentation, referral to an otolaryngologist, and treatment; each may affect the patient’s outcome. Resistance points vary by disease, patient population, healthcare system, and public policy. Insurance, healthcare facilities in geographic proximity, affordability, and referral pathway support can help overcome resistance points [15].

Global Metrics for Disparities in Otolaryngology Care

Healthcare disparities are local, national, and global in scale. Globally, five billion people lack timely access to surgical and anesthesia care; the majority of these individuals are from low/middle-income countries (LMICs) [16]. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery (LCoGS) recommended six metrics to measure access to timely, high quality, and affordable surgical care (Table 1) [16]. These measures have informed national surgical action plans and can be applied to otolaryngology [17,18,19,20,21,22].

Healthcare Disparities Across Otolaryngology Subspecialities

In this section, we discuss the evidence-based healthcare disparities across otolaryngology subspecialities.

Disparities in Head and Neck Cancer

HNC is the seventh most common cancer in the world, accounting for 3% of cancer deaths globally [23]. There are severe disparities in HNC prevalence and outcomes compared to other cancers [24].

Race and Ethnicity

A systematic review on health disparities in HNC found that 77% of the 148 reviewed articles in HNC examined race/ethnicity [25••]. Risk of HNC differs by race/ethnicity because of modifiable risk factors such as systemic racism, occupational exposures such as asbestos [26, 27], and lack of preventative care such as HPV vaccination. HPV- oropharyngeal cancer was more common among Black individuals (55.3%) compared to White individuals (30.3%) [28]. The incidence of HPV + oropharyngeal cancer is declining among Black individuals [29], but oral HPV infection is higher in Black individuals (9.8%) versus White (7.5%), Hispanic (7.2%), and Asian American (3.0%) individuals [30]. This is likely due to disparities in HPV awareness [31] and vaccination rates, concerning for future cancer risk [32]. The incidence of laryngeal cancer among Black males is higher compared to White males [29]. Nationally, Black patients disproportionately present at a younger age with advanced-stage laryngeal cancer and have nodal metastases compared to other races [33]. For oral cavity cancer, there is a higher incidence in Native American and Asian American/Pacific Islander populations [29]. Laotian individuals have 18.04 times higher risk of developing this nasopharyngeal carcinoma than non-Hispanic White individuals [34]. Compared to White patients, American Indian patients had a greater risk of alcohol abuse (68% vs 42%), current smoking (67% vs 49%), living more than 1 h away from a cancer center (81% vs 30%), and delayed presentation with stages III and IV HNC (74% vs 55%) [35].

Significant racial and ethnic disparities also exist for HNC survival. A systematic review and meta-analysis reported that Black patients have inferior survival than White patients for HPV- oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma [36]. Another meta-analysis found that Black HNC patients have poorer survival versus White individuals with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.27 after controlling for socioeconomic factors [37]. In oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, Black patients had worse survival compared to White patients (HR 1.22), after controlling for age, stage, and treatment [28]. The 5-year overall survival for laryngeal cancer was also lower for Black patients (52.7%) compared to White (60.6%), Hispanic (59.5%), and Asian (65.7%) patients [33]. American Indian patients with HNC and nasopharyngeal cancer experience worse survival compared with White patients [35, 38]. These racial/ethnic disparities call for interventions to eliminate the underlying factors.

Insurance and Socioeconomic Status

Low SES increases risks of worse health outcomes for HNC through multiple mechanisms (Fig. 3). A systematic review found that the risk of oral cancer is over 200% higher in low-income countries compared to high-income countries [39]. In the USA, low income, low education level, minority status, and lack of health insurance were each associated with advanced stage at presentation for HNC, with poverty most predictive [40]. The incidence rate of HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer was higher among individuals with lower median household income [28]; lower SES was associated with worse survival [28]. Low SES is associated with advanced T-stage presentation and p16-negative status [41].

Robust insurance and financial resources increase patients’ ability to prevent and present early with HNC. The Affordable Care Act decreased the number of uninsured Americans from 50 to 27 million, with improved access to surgical care due to Medicaid expansion [42]. Insurance coverage does not fully protect against out-of-pocket costs. Relative out-of-pocket expenses for HNC patients was found to be 3.93% of patients’ income compared to 3.07% of income for patients with other types of cancers [24]. Medicaid insurance is often not as robust as private coverage. HNC patients with Medicaid present at a later stage with larger tumor size, more distant metastases, and more lymph node involvement at diagnosis versus privately insured patients [43]. Medicaid patients are less likely to receive indicated surgical treatment [43]. Sittig et al. reported that 5-year overall survival for HNC patients with Medicaid, Medicare, or other government insurance was 50.6% compared to 65.5% for those with private insurance [44]. Within the USA, uninsured status was associated with higher mortality for HPV + oropharyngeal cancer (HR 3.12) [45]. Patients presenting with advanced-stage laryngeal cancer were more likely to be uninsured or have Medicaid [46]. Laryngectomy patients with Medicaid had increased length of stay and associated hospital charges compared to privately insured patients [47]. Insurance status also affects risk of mortality for laryngeal cancer. Among patients with advanced-stage laryngeal cancer, Medicaid patients have a 57% increased risk of mortality compared to those with private insurance [48].

Rurality

“Timely access to care” is challenging for rural areas in the USA and globally [16]. US otolaryngologists are disproportionately in high-income urban areas [49,50,51]. Rural counties therefore have fewer otolaryngologists per population [51]. The incidence and death rates from smoking-related cancers including laryngeal cancer are higher for rural residents [52]. Residence in a county with two or fewer otolaryngologists was found to be associated with poorer survival for HNC patients [40]. Rural individuals may have to travel much farther to see an otolaryngologist, making it harder to access specialty HNC care. Among HNC survivors, those in rural areas report lower health-related quality of life than those living in urban areas [53]. Moreover, the suicide rates for HNC patients living in rural areas are higher than the general population and those living in urban areas [54].

Sex and Gender

Disparities have been shown based on patient biological sex and gender identity. Males have a higher risk of HNC [55]. One study in Korea found that the incidence rate of HNC was 0.19 in males compared to 0.06 in females, even when controlled for smoking and alcohol use [55]. Female patients present with more advanced laryngeal cancer than male patients [46], but have lower mortality rates [56]. Women with non-oropharyngeal HNC had better 5-year overall survival than men (56.3% versus 54.4%, respectively) [57]. Gender also plays a role in clinical trial participation. Although women make up 26.2% of the HNC patients in the USA, they comprise only 17% of patients in HNC clinical trials [58].

Patient Language and Health Literacy

Patients with limited English language proficiency (LEP) and lower health literacy have reduced access to care and poorer outcomes. Patients may not understand risk factors, treatment recommendations, or instructions for recovery. Low education level was associated with an increased risk of HNC (OR 2.50) [39]. Approximately 13.8% of the HNC survivors have inadequate health literacy [59]. Patients with LEP were underrepresented in most outpatient specialty clinics including otolaryngology [60]. Morris et al. found that the incidence rate of papillary thyroid cancer were lower in the counties with non-English speaking individuals without a high school degree, showing reduced healthcare access for these individuals [61]. Language support resources can reduce these barriers.

Disparities in Otology

A recent systematic review on disparities in otology included 52 research articles. Publications most commonly focused on racial/ethnic disparities [62•].

Race and Ethnicity

Disparities in race/ethnicity in otologic disease severity at presentation are well described. Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations have larger vestibular schwannomas at diagnosis versus White patients [63]. In the all-African American Jackson Heart Study prospective cohort, 29.5% of participants had tinnitus, highlighting the high prevalence [64]. There are racial/ethnic disparities in undergoing otologic surgical treatment. Non-Hispanic White patients were more likely than non-White patients to undergo surgery for recurrent acute otitis media or chronic otitis media with effusion that provided significant improvement in quality of life [65]. Compared to White patients, patients who identified as a racial minority were half as likely to pursue cochlear implantation despite qualifying for the procedure [66]. This may be due to racism, patient-provider interactions, social stigma, financial cost, insurance status/type, or lack of educational outreach [67]. Postoperative complication rates are inequitable. African American patients had more skin-site complications after bone-anchored hearing aid implantation compared to other racial/ethnic groups [68].

Insurance and Socioeconomic Status

Better insurance coverage and higher SES both improve access to otologic treatments. Patients with Medicare who were also eligible for Medicaid were 41% less likely to use hearing care services such as visit to audiologists and hearing therapists and purchase of hearing aids, and twice as likely to report hearing issues with their hearing aids compared to high-income Medicare patients [69]. Nieman et al. conducted a successful community-delivered hearing care intervention for low-income and African American older adults with hearing loss in Baltimore. The intervention included training sessions to use a listening device, educational sessions on age-related hearing loss, counseling sessions on optimizing communication, and a brief aural rehabilitation session. After 3 months, they found improved outcomes [70].

Children with higher family income and parental education are more likely to receive cochlear implants at a younger age [71]. Similarly, adults with military insurance were 13 times more likely to receive cochlear implants than adults with Medicaid [66]. Medicaid-insured children receiving cochlear implants have fivefold greater odds of postoperative complications than those with private insurance [72]. This may be partly due to more missed follow-up appointments for children with Medicaid, which could serve as an intervention target. Education level and occupation have been found to influence timing of care for hearing loss [73]. Tran et al. found that patients with inadequate health literacy were more likely to present with more severe hearing loss [74]. Another study found that the is a higher incidence of chronic otitis media among patients that belong to a region with lower education level [75].

Rurality

Hearing loss and hearing impairment are more prevalent in residents of rural counties compared to urban counties, likely due to occupational and recreational noise exposure in rural areas where farming is a common source of income [76]. Rural residents described lack of geographic proximity to hearing care as a major barrier [76]. Rural residents have longer commutes to cochlear implantation centers versus urban residents [77, 78]. The time interval between onset of hearing loss and cochlear implantation was also greater for rural adult patients [77]. Children from rural regions with congenital hearing loss obtained hearing aids at the median age of 47.7 weeks after birth compared to only 26 weeks for urban children [79]. Similarly, rural children received cochlear implants at the median age of 182 weeks after birth compared to 104 weeks for urban children, highlighting the delayed care for the children in rural counties [79]. Rurality is also associated with lower income and Medicaid coverage which exacerbates geographic barriers [77, 78].

Disparities in Rhinology

Healthcare disparities in rhinology are well established in certain domains, such as with allergic fungal rhinosinusitis (AFRS) and exposures to allergens, fungus, and pollution that contribute to allergic rhinitis, upper airway disease, and asthma.

Race and Ethnicity

White patients are significantly more likely to have seen a physician for their sinonasal symptoms compared to patients who identify as Hispanic and Native American [80]. From a language perspective, English-speaking patients were more likely to see a physician for their sinonasal symptoms compared to Spanish-speaking patients [80]. A study in South Florida found that Hispanic individuals tend to have a higher risk of severe chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and longer sinonasal symptom duration compared to non-Hispanic individuals [81]. Another study found that disproportionately fewer Black patients seek tertiary rhinology care than Black residents in southeast Wisconsin (9.3% vs. 13.8%) [82]. A retrospective study on AFRS consisted of significantly more African American patients with Medicaid or no insurance than expected [83]. Patients with AFRS were more likely to be residing in counties with higher poverty level, lower income level, and higher number of African American individuals than CRS [83]. Patients who identified as Black or Hispanic and were hospitalized for epistaxis had increased incidence of complications, longer length of stay, and consequently higher hospital charges compared to White patients [84].

Patients from minority racial and ethnic groups are underrepresented in endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) outcome studies and CRS clinical trials. A cohort study investigating ESS outcomes reported that only 18% of the CRS patients electing ESS belonged to minority groups compared to the national average of 35% [85]. A systematic review found that among patients enrolled in prospective CRS clinical trials between 2010 and 2020 in the USA, 81.67% identified as White, 5.35% as Black, 1.27% as Asian, and 0.12% as American Indian [86]. Additionally, patient reported outcome metrics are often not implemented in non-academic centers or with patients with limited English proficiency [87]. Patients with increased healthcare access are more likely to be diagnosed with rhinologic conditions, therefore leading to inadequate data regarding true disease burden.

Insurance and Socioeconomic Status

Patients with CRS had longer wait times for ESS at public hospitals compared to private hospitals (68 days versus 45 days) and were more likely to be lost to follow-up [88]. Most (86%) public hospital patients with CRS in one local New York City study had Medicaid or no insurance compared to only 4% of CRS patients at private hospitals with better quality [88]. Another study reported that 60% of patients receiving tertiary rhinology care for CRS at an academic medical center in southeast Wisconsin had private insurance compared to only 49.8% of patients generally seen at the medical center [82]. Medicaid and self-pay insurance status were associated with ED presentation for acute rhinosinusitis among adult and pediatric patient population [89], likely reflecting poor access to primary care. Among patients with CRS electing ESS, patients with higher household income were more than twice as likely to experience a clinically meaningful quality of life improvement after ESS compared to patients with lower income level [90].

Climate Change

Climate change is exacerbating rhinologic disparities and is a growing focus in rhinology. Weather extremes induced by global warming have changed pollination patterns and may exacerbate allergic rhinitis and asthma. Worsening air pollution affects allergen-mediated respiratory diseases such as CRS [91]. This will disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minority groups and individuals with low SES, exacerbating disparities.

Disparities in Laryngology

A systematic review in adult laryngology found that disparities based on race/ethnicity were most frequently studied while the most commonly examined condition was laryngeal cancer [92•]. We have included laryngeal cancer in the head and neck cancer section and summarize other disparities below.

Race and Ethnicity

Individuals who identify as African American, Hispanic, or other minority race or ethnicity are less likely to report voice problems compared to White individuals [93], highlighting barriers to presentation. Additionally, Hispanic patients with voice disorders are more likely to delay care because they could not reach a medical office by telephone and due to long wait times at the doctor’s office compared to White patients [93]. These disparities also exist for complication rates. Black patients are more likely to have iatrogenic laryngotracheal stenosis compared to White patients [94]. Moreover, among patients with laryngotracheal stenosis, Black patients are more likely to have a temporary tracheostomy as well as be dependent on tracheostomy compared to White patients [94]. After stroke, Asian patients are more likely to experience poststroke dysphagia (OR 1.73) compared to Caucasian individuals [95].

Biologic Sex, Gender, and Gender Affirming Voice Treatment

Men are less likely to report voice disorders compared to women. 63.9% of women report voice disorders compared to only 36.1% men [96]. However, women are less likely to be referred to an otolaryngologist for their voice disorder compared to men [97]. On the other hand, women are more likely to receive treatment for their voice disorders compared to men [98].

Transgender voice care is a rapidly growing area of focus in laryngology. Transgender and nonbinary (TGNB) individuals have historically been marginalized in society and are vulnerable to healthcare access limitations [99]. About 27% of TGNB people living in rural areas travel more than 75 miles to access gender affirming medical care [100]. Travel is a barrier to gender-affirming healthcare needs such as voice therapy that requires frequent sessions. A 2015 US transgender survey revealed that 46% of transfeminine respondents who want to pursue behavioral voice therapy have not received it yet [100]. Roblee et al. suggested that the use of telehealth may be beneficial in mitigating barriers to voice therapy care, particularly for TGNB people living in rural counties.

Disparities in Pediatric Otolaryngology

Several systematic reviews describe the incidence, prevalence, management, and outcomes of various pediatric otolaryngologic diseases [101,102,103]. A systematic review on disparities reported that pediatric otologic diseases were most frequently studied and the most cited disparities include race and ethnicity, insurance status, and SES [101].

Race and Ethnicity

Numerous studies have reported differences in the prevalence and management of pediatric otolaryngologic diseases based on race and ethnicity [103]. A 2011 systematic review reported that Black children may have greater risk and higher prevalence for sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) compared to non-Black children [104, 105]. Black and Hispanic children are less likely to be diagnosed with frequent ear infections, hay fever, streptococcal pharyngitis, and sinusitis compared to White children, highlighting lack of access to care and underdiagnosis in children from racial and ethnic minority groups [106]. Hispanic children with thyroid cancer present with 27-mm tumor compared to 20 mm for White children [107]. Racial disparities in surgical interventions are well described. White children are more likely to undergo adenotonsillectomy compared to Black or Hispanic children [104, 108]. According to the 2014 National Health Interview Survey, 12.6% White children received tympanostomy tubes for ear infections compared to only 4.8% of Black children and 4.4% of Hispanic children [109]. Black and Hispanic children are less likely to receive cochlear implantation early compared to White children [110]. Children from minority groups suffer more complications. Hispanic children have been found to have a higher mortality rate (28%) following tracheostomy than non-Hispanic White (7.9%) and non-Hispanic Black (8.7%) children [111]. Black children are more likely to have laryngeal stenosis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and an extended length of hospital stay following tracheostomies compared to White children [112].

Insurance and Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic disadvantage is the most studied factor contributing to healthcare disparities within pediatric otolaryngology. Spilsbury et al. found that children living in neighborhoods with severe socioeconomic disadvantage are more likely to be diagnosed with pediatric obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), even after controlling for premature birth, obesity, and race [113]. Children with public insurance have lower access to specialty care than those with private insurance. One study measured children’s access to specialty care including otolaryngology care for common health conditions such as OSA and chronic bilateral otitis media [114]. They found that 66% of children with Medicaid were denied an appointment at specialty clinics, compared to 11% of children with private insurance [114]. Among 89 specialty clinics that accepted both insurance types, the average wait time for children with Medicaid was 22 days longer than that for privately insured children [114]. Children with Medicaid waited longer to be referred to an otolaryngologist for acute otitis media versus those with private insurance [115]. As mentioned in the otology section, children with public insurance are diagnosed with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) later than those with private insurance (20 versus 4 months age) and wait longer after diagnosis to receive cochlear implantation (25.5 versus 11 months) [116]. Children with Medicaid and self-pay insurance status are more likely to present to the ED for acute rhinosinusitis, highlighting problems accessing primary care [89, 117]. Among pediatric patients with acute bacterial sinusitis, those with Medicaid or no insurance had higher rates of complications compared to those with private insurance [100].

Other

Some studies have highlighted family factors contributing to disparities among children within otolaryngology. Children with SNHL referred for cochlear implantation were more likely to have married parents (91% versus 70%)[118]. Another study found that children were less likely to attend their appointment at otologic medical clinics if their parents were younger with lower education level [119].

Disparities in Comprehensive Otolaryngology and Sleep Otolaryngology

Healthcare disparities also exist for conditions seen mostly by general otolaryngologists such as adult obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and adult tonsillar diseases. A case–control study found that African American patients with sleep disordered breathing (SDB) are younger than Caucasian patients, suggesting that young African American individuals may have an increased risk of sleep apnea compared to young White individuals [120]. Black female patients with OSA are significantly younger at the time of diagnosis than White female patients and Black male patients with OSA have significantly lower oxygen saturation levels than White male patients [121]. Black male patients also present with more severe OSA at diagnosis with mean apnea hypopnea index of 52.4 ± 39.4 events/h compared with 39.0 ± 28.9 in White male patients, suggesting delayed diagnosis [122]. This study also found that Black male patients were 1.61 times more likely to have witnessed apneas and 1.56 times more likely to have drowsy driving at the time of OSA diagnosis compared to White male patients [122]. Black patients have decreased rates of surgery for OSA [123]. Lower household income, female sex, and Black and Hispanic race were associated with increased revisits for acute pain after adult tonsillectomy [124].

Disparities in Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

Healthcare disparities in aesthetic and reconstructive surgery are less well studied. One of the most serious complications of reconstructive flap surgery is postoperative sepsis. Sparenberg et al. found that African American race and male gender were significantly associated with sepsis following a reconstructive flap surgey [125]. Among HNC patients receiving free flap reconstruction, patients with Medicaid or no insurance were more likely to experience wound-related complications such as flap failure, fistula formation, donor site or primary site breakdown, and infection [126]. Another study reported that age over 55 years is associated with major medical complications following free flap reconstruction of the head and neck [127]. Other areas with significant attention include cultural and racial/ethnic differences in desired cosmetic surgery outcomes such as facial rejuvenation and appropriate dermatologic care for different skin tones. Keloid formation has been another topic of study with differences based on race/ethnicity [128, 129].

Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Healthcare Disparities in Otolaryngology

The USA has significant healthcare disparities despite having the world’s most expensive healthcare system [130]. This is partly due to underinvestment in a social safety net and public health. The COVID-19 pandemic focused efforts on SDH.

The COVID-19 pandemic further compromised access to care and exacerbated disparities. Otolaryngology had among the most severe reductions in surgical volume and outpatient visits in the USA [131]. Massachusetts noted a 63% decrease in otolaryngology office visits and a greater decrease in operative procedures [132]. Consequently, there was an increase in the number of advanced presentations such as orbital emergencies due to acute sinusitis [133]. Black and Hispanic children and those with Medicaid were disproportionately less likely to attend otolaryngology appointments [134]. During the pandemic, patients with Medicaid and lower income presented with higher disease severity for CRS and SNHL compared to those with private insurance and higher income [135]. An equity approach is needed to transform how we recover from the pandemic and improve access to healthcare.

Otolaryngology Workforce

The diversity of the otolaryngology workforce significantly influences access to affordable, high value otolaryngologic care. Racial and ethnic concordance between providers and patients leads to improved communication, increased patient satisfaction, and greater healthcare utilization which minimizes delays in care [136, 137]. Moreover, physicians from minority racial and ethnic groups are more likely to provide care to patients in medically underserved areas who may be low-income, uninsured, or insured with Medicaid [138, 139]. However, the demographics of the otolaryngology workforce in the USA do not match those of the general population. In 2016, African American individuals comprised 12.6% of the US population but made up only 2.1% of otolaryngology residents and 2.4% of otolaryngology faculty [140]. Similarly, Hispanic individuals are underrepresented at all levels in otolaryngology compared to the general US population. Only 5.5% of otolaryngology residents self-identified as Hispanic compared to 17% of the US population in 2016 [140]. Women are also a minority in the field of otolaryngology, accounting for only 17.1% of practicing otolaryngologists in the USA in 2020 [141]. It is pertinent to implement strategies nationwide to create a diverse otolaryngologic workforce to help mitigate healthcare disparities.

Achieving Health Equity in Otolaryngology

The field of otolaryngology has focused on detecting disparities and identifying potential factors involved, but progress can be made in identifying actionable targets for intervention to eliminate these disparities [12, 142]. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education reported that less than 5% of participating institutions had a systematic approach in place to address healthcare disparities within their organizations between 2017 and 2020 [143]. Therefore, there must be an urgent call to action to focus on identifying solutions and implementing strategies to reduce and eventually eliminate healthcare disparities (Table 2).

Conclusions

The need to eliminate healthcare disparities in otolaryngology has been recognized through the abundance of research studies in the field. These studies have identified disparities across all areas in otolaryngology for many vulnerable groups that include racial and ethnic minority groups, low-income populations, and individuals from rural areas among many others. However, there have been little effort in developing and implementing interventions to reduce these disparities.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Disparities | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Agency for healthcare research and quality. Accessed 31 Jan 2023. https://www.ahrq.gov/topics/disparities.html.

National Academies of Sciences E, Division H and M, Practice B on PH and PH, et al. The State of health disparities in the United States. In: The State of Health Disparities in the United States. National Academies Press (US); 2017. Accessed January 31, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425844/.

Hernandez SM, Sparks PJ. Barriers to health care among adults with minoritized identities in the United States, 2013–2017. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(6):857–62. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305598.

Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q. 2019;97(2):407–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12390.

Kullgren JT, McLaughlin CG, Mitra N, Armstrong K. Nonfinancial barriers and access to care for U.S. adults. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1 Pt 2):462–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01308.x.

Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK. Traveling towards disease: transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health. 2013;38(5):976–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9681-1.

Caraballo C, Ndumele CD, Roy B, et al. Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in barriers to timely medical care among adults in the US, 1999 to 2018. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(10):e223856. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3856.

Cheung PT, Wiler JL, Lowe RA, Ginde AA. National study of barriers to timely primary care and emergency department utilization among Medicaid beneficiaries. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):4-10.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.01.035.

Jackson CL, Agénor M, Johnson DA, Austin SB, Kawachi I. Sexual orientation identity disparities in health behaviors, outcomes, and services use among men and women in the United States: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):807. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3467-1.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social Determinants of Health. Healthy People 2030. Accessed 9 Feb 2023. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health.

Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2113–21. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.077628.

Bowe SN, Megwalu UC, Bergmark RW, Balakrishnan K. Moving beyond detection: charting a path to eliminate health care disparities in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1013–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221094460.

Rutherford PA, Provost LP, Kotagal UR, Luther K, Anderson A. Achieving hospital-wide patient flow | IHI - Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Accessed 7 Sep 2022. https://www.ihi.org:443/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/Achieving-Hospital-wide-Patient-Flow.aspx.

Eisenberg JM, Power EJ. Transforming insurance coverage into quality health care: voltage drops from potential to delivered quality. JAMA. 2000;284(16):2100–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.16.2100.

Bergmark RW, Burks CA, Schnipper JL, Weissman JS. Understanding and investigating access to surgical care. Ann Surg. 2022;275(3):492–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005212.

Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. The Lancet. 2015;386(9993):569–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X.

Guest GD, McLeod E, Perry WRG, et al. Collecting data for global surgical indicators: a collaborative approach in the Pacific Region. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(4):e000376. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000376.

Dahir S, Cotache-Condor CF, Concepcion T, et al. Interpreting the Lancet surgical indicators in Somaliland: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e042968. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042968.

Bergmark RW, Shaye DA, Shrime MG. Surgical care and otolaryngology in global health. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018;51(3):501–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2018.01.001.

Shrime MG, Dare AJ, Alkire BC, O’Neill K, Meara JG. Catastrophic expenditure to pay for surgery: a global estimate. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(02):S38-S44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70085-9.

Alkire BC, Raykar NP, Shrime MG, et al. Global access to surgical care: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(6):e316-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)70115-4.

Patterson RH, Fischman VG, Wasserman I, et al. Global burden of head and neck cancer: economic consequences, health, and the role of surgery. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2020;162(3):296–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599819897265.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21654.

Massa ST, Osazuwa-Peters N, Adjei Boakye E, Walker RJ, Ward GM. Comparison of the financial burden of survivors of head and neck cancer with other cancer survivors. JAMA Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2019;145(3):239–249. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.3982.

•• Nallani R, Subramanian TL, Ferguson-Square KM, et al. A systematic review of head and neck cancer health disparities: a call for innovative research. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1238–1248. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221077197. This systemic review summarizes the existing healthcare disparities in Head and Neck Cancer by reviewing 148 articles and identifies gaps in this research area.

Bravi F, Lee YCA, Hashibe M, et al. Lessons learned from the INHANCE consortium: an overview of recent results on head and neck cancer. Oral Dis. 2021;27(1):73–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13502.

Juon HS, Hong A, Pimpinelli M, Rojulpote M, McIntire R, Barta JA. Racial disparities in occupational risks and lung cancer incidence: analysis of the National Lung Screening Trial. Prev Med. 2021;143:106355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106355.

Rotsides JM, Oliver JR, Moses LE, et al. Socioeconomic and racial disparities and survival of human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(1):131–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820935853.

Mazul AL, Chidambaram S, Zevallos JP, Massa ST. Disparities in head and neck cancer incidence and trends by race/ethnicity and sex. Head Neck. 2023;45(1):75–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.27209.

Choi JS, Tang L, Yu AJ, et al. Prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infections by race in the United States: an association with sexual behavior. Oral Dis. 2020;26(5):930–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/odi.13292.

Ojeaga A, Alema-Mensah E, Rivers D, Azonobi I, Rivers B. Racial disparities in HPV-related knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among African American and white women in the U.S. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2019;34(1):66–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-017-1268-6.

Harrington N, Chen Y, O’Reilly AM, Fang CY. The role of trust in HPV vaccine uptake among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States: a narrative review. AIMS Public Health. 2021;8(2):352–68. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2021027.

Shin JY, Truong MT. Racial disparities in laryngeal cancer treatment and outcome: a population-based analysis of 24,069 patients. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(7):1667–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25212.

Wang Q, Xie H, Li Y, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in nasopharyngeal cancer with an emphasis among Asian Americans. Int J Cancer. 2022;151(8):1291–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34154.

Dwojak SM, Finkelstein DM, Emerick KS, Lee JH, Petereit DG, Deschler DG. Poor survival for American Indians with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(2):265–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599814533083.

Stein E, Lenze NR, Yarbrough WG, Hayes DN, Mazul A, Sheth S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of racial survival disparities among oropharyngeal cancer cases by HPV status. Head Neck. 2020;42(10):2985–3001. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26328.

Russo DP, Tham T, Bardash Y, Kraus D. The effect of race in head and neck cancer: a meta-analysis controlling for socioeconomic status. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(6):102624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102624.

Challapalli SD, Simpson MC, Adjei Boakye E, et al. Survival differences in nasopharyngeal carcinoma among racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol Off J ENT-UK Off J Neth Soc Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Cervico-Facial Surg. 2019;44(1):14–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13225.

Conway DI, Petticrew M, Marlborough H, Berthiller J, Hashibe M, Macpherson LMD. Socioeconomic inequalities and oral cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(12):2811–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.23430.

Pagedar NA, Davis AB, Sperry SM, Charlton ME, Lynch CF. Population analysis of socioeconomic status and otolaryngologist distribution on head and neck cancer outcomes. Head Neck. 2019;41(4):1046–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25521.

Emerson MA, Farquhar DR, Lenze NR, et al. Socioeconomic status, access to care, risk factor patterns, and stage at diagnosis for head and neck cancer among black and white patients. Head Neck. 2022;44(4):823–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26977.

Dickman SL, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Inequality and the health-care system in the USA. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017;389(10077):1431–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30398-7.

Agarwal P, Agrawal RR, Jones EA, Devaiah AK. Social determinants of health and oral cavity cancer treatment and survival: a competing risk analysis. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(9):2160–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28321.

Sittig MP, Luu M, Yoshida EJ, et al. Impact of insurance on survival in patients < 65 with head & neck cancer treated with radiotherapy. Clin Otolaryngol Off J Ent-UK Off J Neth Soc Oto-Rhino-Laryngol Cervico-Facial Surg. 2020;45(1):63–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13467.

Pike LRG, Royce TJ, Mahal AR, et al. Outcomes of HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: impact of race and socioeconomic status. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw JNCCN. 2020;18(2):177–84. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2019.7356.

Chen AY, Schrag NM, Halpern M, Stewart A, Ward EM. Health insurance and stage at diagnosis of laryngeal cancer: does insurance type predict stage at diagnosis? Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(8):784–90. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.133.8.784.

Mehta V, Flores JM, Thompson RW, Nathan CA. Primary payer status, individual patient characteristics, and hospital-level factors affecting length of stay and total cost of hospitalization in total laryngectomy. Head Neck. 2017;39(2):311–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24585.

Chen AY, Halpern M. Factors predictive of survival in advanced laryngeal cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(12):1270–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.133.12.1270.

Liu DH, Ge M, Smith SS, Park C, Ference EH. Geographic distribution of otolaryngology advance practice providers and physicians. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2022;167(1):48–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998211040408.

Vickery TW, Weterings R, Cabrera-Muffly C. Geographic distribution of otolaryngologists in the United States. Ear Nose Throat J. 2016;95(6):218–23.

Gadkaree SK, McCarty JC, Siu J, et al. Variation in the geographic distribution of the otolaryngology workforce: a national geospatial analysis. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2020;162(5):649–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820908860.

Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Thomas CC, Massetti GM, Peaker B, Richardson LC. Invasive Cancer incidence, 2004–2013, and deaths, 2006–2015, in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties - United States. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ Wash DC 2002. 2017;66(14):1–13. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6614a1.

Adamowicz JL, Christensen A, Howren MB, et al. Health-related quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors: evaluating the rural disadvantage. J Rural Health Off J Am Rural Health Assoc Natl Rural Health Care Assoc. 2022;38(1):54–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12571.

Osazuwa-Peters N, Barnes JM, Okafor SI, et al. Incidence and risk of suicide among patients with head and neck cancer in rural, urban, and metropolitan areas. JAMA Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2021;147(12):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2021.1728.

Park JO, Nam IC, Kim CS, et al. Sex differences in the prevalence of head and neck cancers: a 10-year follow-up study of 10 million healthy people. Cancers. 2022;14(10):2521. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14102521.

Chen S, Dee EC, Muralidhar V, Nguyen PL, Amin MR, Givi B. Disparities in mortality from larynx cancer: implications for reducing racial differences. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(4):E1147–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29046.

Mazul AL, Naik AN, Zhan KY, et al. Gender and race interact to influence survival disparities in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2021;112:105093. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.105093.

Benchetrit L, Torabi SJ, Tate JP, et al. Gender disparities in head and neck cancer chemotherapy clinical trials participation and treatment. Oral Oncol. 2019;94:32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.05.009.

Nilsen ML, Moskovitz J, Lyu L, et al. Health literacy: Impact on quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(10):2354–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28360.

Himmelstein J, Cai C, Himmelstein DU, et al. Specialty care utilization among adults with limited English proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(16):4130–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07477-6.

Morris LGT, Sikora AG, Tosteson TD, Davies L. The increasing incidence of thyroid cancer: the influence of access to care. Thyroid Off J Am Thyroid Assoc. 2013;23(7):885–91. https://doi.org/10.1089/thy.2013.0045.

• Lovett B, Welschmeyer A, Johns JD, Mowry S, Hoa M. Health Disparities in Otology: A PRISMA-Based Systematic Review. Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1229–1237. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998211039490. This systemic review includes 52 articles on healthcare disparities in otology and identifies the lack of robust data on the effect of social determinants of health on otologic care.

Carlson ML, Marston AP, Glasgow AE, et al. Racial differences in vestibular schwannoma. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(9):2128–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25892.

House L, Bishop CE, Spankovich C, Su D, Valle K, Schweinfurth J. Tinnitus and its risk factors in African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(7):1668–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26964.

Ambrosio A, Brigger MT. Surgery for otitis media in a universal health care model: socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity effects. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2014;151(1):137–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599814525570.

Tolisano AM, Schauwecker N, Baumgart B, et al. Identifying disadvantaged groups for cochlear implantation: demographics from a large cochlear implant program. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2020;129(4):347–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489419888232.

Sims S, Houston L, Schweinzger I, Samy RN. Closing the gap in cochlear implant access for African-Americans: a story of outreach and collaboration by our cochlear implant program. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;25(5):365–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0000000000000399.

Zeitler DM, Herman BS, Snapp HA, Telischi FF, Angeli SI. Ethnic disparity in skin complications following bone-anchored hearing aid implantation. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121(8):549–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348941212100809.

Willink A, Reed NS, Lin FR. Access to hearing care services among older Medicare beneficiaries using hearing aids. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2019;38(1):124–31. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05217.

Nieman CL, Marrone N, Mamo SK, et al. The Baltimore HEARS pilot study: an affordable, accessible, community-delivered hearing care intervention. Gerontologist. 2017;57(6):1173–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw153.

Sharma S, Bhatia K, Singh S, Lahiri AK, Aggarwal A. Impact of socioeconomic factors on paediatric cochlear implant outcomes. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;102:90–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2017.09.010.

Chang DT, Ko AB, Murray GS, Arnold JE, Megerian CA. Lack of financial barriers to pediatric cochlear implantation: impact of socioeconomic status on access and outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136(7):648–57. https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2010.90.

Dagan E, Wolf M, Migirov L. Less education and blue collar employment are related to longer time to admission of patients presenting with unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(12):2417–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.20639.

Tran ED, Vaisbuch Y, Qian ZJ, Fitzgerald MB, Megwalu UC. Health literacy and hearing healthcare use. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(5):E1688–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29313.

Nash R, Fox R, Srinivasan R, Majithia A, Singh A. Demographic factors associated with loss to follow up in the management of chronic otitis media: case-control study. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(2):166–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215115003266.

Powell W, Jacobs JA, Noble W, Bush ML, Snell-Rood C. Rural adult perspectives on impact of hearing loss and barriers to care. J Community Health. 2019;44(4):668–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-019-00656-3.

Hixon B, Chan S, Adkins M, Shinn JB, Bush ML. Timing and impact of hearing healthcare in adult cochlear implant recipients: a rural-urban comparison. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(9):1320–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000001197.

Chan S, Hixon B, Adkins M, Shinn JB, Bush ML. Rurality and determinants of hearing healthcare in adult hearing aid recipients. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(10):2362–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26490.

Bush ML, Burton M, Loan A, Shinn JB. Timing discrepancies of early intervention hearing services in urban and rural cochlear implant recipients. Otol Neurotol Off Publ Am Otol Soc Am Neurotol Soc Eur Acad Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(9):1630–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e31829e83ad.

Hagedorn R, Sumsion J, Alt JA, Gill AS. Disparities in access to health care: a survey-based, pilot investigation of sinonasal complaints in the community care setting. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2023;13(1):76–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.23055.

Levine CG, Casiano RR, Lee DJ, Mantero A, Liu XZ, Palacio AM. Chronic rhinosinusitis disease disparity in the South Florida Hispanic population. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(12):2659–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29664.

Poetker DM, Friedland DR, Adams JA, Tong L, Osinski K, Luo J. Socioeconomic determinants of tertiary rhinology care utilization. OTO Open. 2021;5(2):2473974X211009830. https://doi.org/10.1177/2473974X211009830.

Wise SK, Ghegan MD, Gorham E, Schlosser RJ. Socioeconomic factors in the diagnosis of allergic fungal rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2008;138(1):38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2007.10.020.

Randhawa A, Randhawa KS, Tseng CC, Fang CH, Baredes S, Eloy JA. Racial disparities in charges, length of stay, and complications following adult inpatient epistaxis treatment. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2023;37(1):51–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/19458924221130880.

Soler ZM, Mace JC, Litvack JR, Smith TL. Chronic rhinosinusitis, race, and ethnicity. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26(2):110–6. https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3741.

Spielman DB, Liebowitz A, Kelebeyev S, et al. Race in Rhinology Clinical Trials: A Decade of Disparity. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(8):1722–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29371.

Allar BG, Eruchalu CN, Rahman S, et al. Lost in translation: a qualitative analysis of facilitators and barriers to collecting patient reported outcome measures for surgical patients with limited English proficiency. Am J Surg. 2022;224(1 Pt B):514–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.03.005.

Duerson W, Lafer M, Ahmed O, et al. Health care disparities in patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: differences in disease presentation and access to care. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2019;128(7):608–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003489419834947.

Bergmark RW, Ishman SL, Phillips KM, Cunningham MJ, Sedaghat AR. Emergency department use for acute rhinosinusitis: insurance dependent for children and adults. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(2):299–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26671.

Beswick DM, Mace JC, Rudmik L, et al. Socioeconomic factors impact quality of life outcomes and olfactory measures in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019;9(3):231–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22256.

Kim J, Waugh DW, Zaitchik BF, et al. Climate change, the environment, and rhinologic disease. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. Published online December 28, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.23128.

• Feit NZ, Wang Z, Demetres MR, Drenis S, Andreadis K, Rameau A. Healthcare disparities in laryngology:. a scoping review. Laryngoscope. 2022;132(2):375–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.29325. Findings from this scoping review highlights the sources of healthcare disparities in Laryngology and emphasizes the need for more disparities research in this field.

Hur K, Zhou S, Bertelsen C, Johns MM. Health disparities among adults with voice problems in the United States. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(4):915–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26947.

Plocienniczak M, Sambhu KM, Noordzij JP, Tracy L. Impact of socioeconomic demographics and race on laryngotracheal stenosis etiology and outcomes. Laryngoscope. Published online July 30, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.30321.

Bussell SA, González-Fernández M. Racial disparities in the development of dysphagia after stroke: further evidence from the Medicare database. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(5):737–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.005.

Bertelsen C, Zhou S, Hapner ER, Johns MM. Sociodemographic characteristics and treatment response among aging adults with voice disorders in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngol - Head Neck Surg. 2018;144(8):719–726. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.0980.

Cohen S, Kim J, Roy N, Courey M. Factors influencing referral of patients with voice disorders from primary care to otolaryngology. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(1):https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24280.

Marmor S, Misono S. Treatment receipt and outcomes of self-reported voice problems in the US population aged ≥65 years. OTO Open. 2018;2(2):2473974X18774023. https://doi.org/10.1177/2473974X18774023.

Thompson HM, Clement AM, Ortiz R, et al. Community engagement to improve access to healthcare: a comparative case study to advance implementation science for transgender health equity. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21:104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-022-01702-8.

Roblee CV, Mendes C, Horen SR, Hamidian JA. Remote voice treatment with transgender individuals: a health care equity opportunity. J Voice. 2022;36(4):443–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2022.01.012.

Jabbour J, Robey T, Cunningham MJ. Healthcare disparities in pediatric otolaryngology: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(7):1699–713. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26995.

Pattisapu P, Raol NP. Healthcare equity in pediatric otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2022;55(6):1287–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2022.07.006.

Pritchett CV, Johnson RF. Racial disparities in pediatric otolaryngology: current state and future hope. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;29(6):492–503. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0000000000000759.

Boss EF, Smith DF, Ishman SL. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of sleep-disordered breathing in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(3):299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.11.006.

Morton S, Rosen C, Larkin E, Tishler P, Aylor J, Redline S. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in children with a history of tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy. Sleep. 2001;24(7):823–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/24.7.823.

Shay S, Shapiro NL, Bhattacharyya N. Pediatric otolaryngologic conditions: racial and socioeconomic disparities in the United States. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(3):746–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26240.

Sharma RK, Patel S, Gallant JN, et al. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the presentation and management of pediatric thyroid cancer. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;162:111331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2022.111331.

Cooper JN, Koppera S, Boss EF, Lind MN. Differences in tonsillectomy utilization by race/ethnicity, type of health insurance, and rurality. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(6):1031–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.11.007.

Simon AE, Boss EF, Zelaya CE, Hoffman HJ. Racial and ethnic differences in receipt of pressure equalization tubes among US children, 2014. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(1):88–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.07.004.

Liu X, Rosa-Lugo LI, Cosby JL, Pritchett CV. Racial and insurance inequalities in access to early pediatric cochlear implantation. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(3):667–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820953381.

Watters K, O’Neill M, Zhu H, Graham RJ, Hall M, Berry J. Two-year mortality, complications, and healthcare use in children with medicaid following tracheostomy. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(11):2611–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25972.

Brown C, Shah GB, Mitchell RB, Lenes-Voit F, Johnson RF. The incidence of pediatric tracheostomy and its association among Black children. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(1):206–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820947016.

Spilsbury JC, Storfer-Isser A, Kirchner HL, et al. Neighborhood disadvantage as a risk factor for pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J Pediatr. 2006;149(3):342–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.061.

Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing access to specialty care for children with public insurance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(24):2324–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1013285.

Patel S, Schroeder JW. Disparities in children with otitis media: the effect of insurance status. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1):73–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599810391428.

Armstrong M, Maresh A, Buxton C, et al. Barriers to early pediatric cochlear implantation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77(11):1869–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.08.031.

Bergmark RW, Ishman SL, Scangas GA, Cunningham MJ, Sedaghat AR. Socioeconomic determinants of overnight and weekend emergency department use for acute rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(11):2441–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25390.

Wiley S, Meinzen-Derr J. Access to cochlear implant candidacy evaluations: who is not making it to the team evaluations? Int J Audiol. 2009;48(2):74–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020802475227.

Kavanagh KT, Smith TR, Golden GS, Tate NP, Hinkle WG. Multivariate analysis of family risk factors in predicting appointment attendance in a pediatric otology and communication clinic. J Health Soc Policy. 1991;2(3):85–102. https://doi.org/10.1300/J045v02n03_06.

Redline S, Tishler PV, Hans MG, Tosteson TD, Strohl KP, Spry K. Racial differences in sleep-disordered breathing in African-Americans and Caucasians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(1):186–92. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001310.

Meetze K, Gillespie MB, Lee FS. Obstructive sleep apnea: a comparison of black and white subjects. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(7 Pt 1):1271–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200207000-00024.

Thornton JD, Dudley KA, Saeed GJ, et al. Differences in symptoms and severity of obstructive sleep apnea between black and white patients. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19(2):272–8. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202012-1483OC.

Cohen SM, Howard JJM, Jin MC, Qian J, Capasso R. Racial disparities in surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. OTO Open. 2022;6(1):2473974X221088870. https://doi.org/10.1177/2473974X221088870.

Bhattacharyya N. Healthcare disparities in revisits for complications after adult tonsillectomy. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36(2):249–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2014.11.004.

Sparenberg S, Blankensteijn LL, Ibrahim AM, Peymani A, Lin SJ. Risk factors associated with the development of sepsis after reconstructive flap surgery. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2019;53(6):328–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/2000656X.2019.1626738.

Rohlfing ML, Mays AC, Isom S, Waltonen JD. Insurance status as a predictor of mortality in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(12):2784–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26713.

Haughey BH, Wilson E, Kluwe L, et al. Free flap reconstruction of the head and neck: analysis of 241 cases. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2001;125(1):10–7. https://doi.org/10.1067/mhn.2001.116788.

Brissett AE, Naylor MC. The aging African-American face. Facial Plast Surg FPS. 2010;26(2):154–63. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1253501.

Margiotta E, Ramras S, Shteynberg A. Recurrence of primary and secondary keloids in a select African American and Afro-Caribbean population. Ann Plast Surg. 2022;88(3 Suppl 3):S194–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000003173.

Health - OECD Data. Accessed 7 Sep 2022. https://data.oecd.org/health.htm.

Losenegger T, Urban MJ, Jagasia AJ. Challenges in the Delivery of Rural Otolaryngology Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2021;165(1):5–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599821995146.

Fan T, Workman AD, Miller LE, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on otolaryngology community practice in Massachusetts. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2021;165(3):424–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820983732.

Fastenberg JH, Bottalico D, Kennedy WA, Sheikh A, Setzen M, Rodgers R. The impact of the pandemic on otolaryngology patients with negative COVID-19 status: commentary and insights from orbital emergencies. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(3):444–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820931082.

Adigwu Y, Osterbauer B, Hochstim C. Disparities in access to pediatric otolaryngology care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2022;131(9):971–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/00034894211048790.

Kim M, Park JA, Cha H, Lee WH, Hong SN, Kim DW. Impact of the COVID-19 and socioeconomic status on access to care for otorhinolaryngology patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(19):11875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911875.

Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282(6):583–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.6.583.

LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A, Jones KE. The association of doctor-patient race concordance with health services utilization. J Public Health Policy. 2003;24(3–4):312–23.

Komaromy M, Grumbach K, Drake M, et al. The role of black and Hispanic physicians in providing health care for underserved populations. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(20):1305–10. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199605163342006.

Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Veloski JJ, Gayle JA. The impact of multiple predictors on generalist physicians’ care of underserved populations. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1225–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.90.8.1225.

Ukatu CC, Welby Berra L, Wu Q, Franzese C. The state of diversity based on race, ethnicity, and sex in otolaryngology in 2016. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(12):E795–800. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.28447.

Cass LM, Smith JB. The current state of the otolaryngology workforce. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2020;53(5):915–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2020.05.016.

Megwalu UC, Raol NP, Bergmark R, Osazuwa-Peters N, Brenner MJ. Evidence-based medicine in otolaryngology, part XIII: health disparities research and advancing health equity. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1249–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221087138.

Koh N, Wagner R, Newton R, Kuhn C. CLER National Report of Findings 2021. Published online 2021.

Haas JS, Linder JA, Park ER, et al. Proactive tobacco cessation outreach to smokers of low socioeconomic status: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):218–26. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6674.

Grubbs SS, Polite BN, Carney J, et al. Eliminating racial disparities in colorectal cancer in the real world: it took a village. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31(16):1928–30. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.47.8412.

Smith DH, Case HF, Quereshy HA, et al. Geographic distribution of otolaryngology training programs and potential opportunities for strategic program growth. Laryngoscope. Published online August 23, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.30361.

Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, et al. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(4):e3–28. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302987.

Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x.

Karmali K, Grobovsky L, Levy J, Keatings M. Enhancing cultural competence for improved access to quality care. Healthc Q Tor Ont. 2011;14 Spec No 3:52–57. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcq.2011.22578.

FitzGerald C, Martin A, Berner D, Hurst S. Interventions designed to reduce implicit prejudices and implicit stereotypes in real world contexts: a systematic review. BMC Psychol. 2019;7(1):29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0299-7.

Burks CA, Russell TI, Goss D, et al. Strategies to increase racial and ethnic diversity in the surgical workforce: a state of the art review. Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg Off J Am Acad Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2022;166(6):1182–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/01945998221094461.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Sana Batool has nothing to disclose. Ciersten A. Burks reports United Against Racism Subspeciality Grant, Mass General Brigham. Regan W. Bergmark reports Nesson Fellow, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Institutional faculty grant funding and salary support for research on disparities in timely access to high quality surgical care); United Against Racism Subspeciality Grant, Mass General Brigham; Grant funding, I-Mab Biopharma.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Batool, S., Burks, C.A. & Bergmark, R.W. Healthcare Disparities in Otolaryngology. Curr Otorhinolaryngol Rep 11, 95–108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-023-00459-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-023-00459-0