Abstract

Introduction

To elucidate the perceptions on eye care of patients affected by the disruption of outpatient and surgical ophthalmological services during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A cross-sectional questionnaire-based survey was conducted during the reopening of outpatient services at two tertiary eye care centres in Singapore and North India. Consecutive patients were recruited from general and specialist eye clinics in June 2020.

Results

A total of 326 patients were recruited, 200 patients from Singapore and 126 patients from New Delhi, India. The most common eye conditions were diabetic retinopathy and uveitis or ocular inflammatory conditions in the Indian centre, whereas the most common in the Singaporean centre were cataract in the pre- or postoperative stage and glaucoma. For patients from the Indian centre, 61.9% felt that COVID-19 had negatively impacted their eye disease, 58.7% were more distressed by their eye disease, 70.8% could not access appropriate eye care, 66.6% were afraid of contracting COVID-19 in the clinic, and 61.9% were accepting of teleconsultations. For patients from the Singaporean centre, 13.5% felt that COVID-19 had negatively impacted their eye disease, 19.5% were more distressed by their eye disease, 21.5% could not access appropriate eye care, 35% were afraid of contracting COVID-19 in the clinic, and only 31% were accepting of teleconsultations.

Conclusion

Patients from India appear to have been more negatively affected by the pandemic compared to patients from Singapore. This study highlights patients’ perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 on eye care, perceived risks, ease of access to care and attitudes towards eye care during the pandemic. Patients’ perceptions are integral in developing strategies for the best care possible. There were heterogeneous responses amongst our patients; hence, there may be a role for more individualized healthcare strategies in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Disruption of outpatient ophthalmological services by the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted patients’ eye care. We aim to explore patients' experiences and perceptions, and propose strategies for future pandemic response. |

What was learned from this study? |

Patients recruited from the Singaporean centre were of older age group, had lower disease burden and were less receptive to telehealth. Patients recruited from the Indian centre were more averse to contracting COVID-19, more distressed about their eye condition and less able to access care needed during lockdown. |

Strategies for future pandemic response may include triaging, decentralised ophthalmic care, teleophthalmology, improving medication access and education to improve patients’ receptiveness to novel eye care strategies. |

Varied responses to our survey signal a need to tailor healthcare strategies to suit patients’ preferences. Lessons learnt from COVID-19 can better prepare us for future pandemic response. |

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has significantly impacted the healthcare landscape throughout the world. On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic and a public health emergency [1]. Ophthalmological practices around the world took different strategies to cope with various lockdown measures and infection control protocols. This included the postponement of elective procedures, non-essential outpatient treatment and consultations, the use of personal protective equipment and heightened safety distancing measures.

According to a WHO survey [2], at least 30% of countries have disrupted services for non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. Singapore issued a nationwide lockdown or ‘circuit-breaker’ [3] where non-essential services were halted and staff were redirected to aid in pandemic response and relief [4]. Whilst in India, 72.5% [5] of ophthalmologists were not seeing any patients during the lockdown period and most of them had switched over to teleconsultations [5]. As such, many patients’ appointments and procedures were put on hold during lockdown until further notice.

Whilst lockdown measures may help curb the spread of COVID-19, they can have a negative impact on other acute non-communicable diseases. Numerous reports internationally have found delayed presentations of life-threatening conditions such as acute stroke [6] and myocardial infarction [7]. As such, we would expect that the pandemic might have a similar negative impact on patients with ophthalmic conditions and delayed presentation of sight-threatening diseases. We aimed to elicit the experiences, expectations and perceptions of patients who were affected by initial lockdown measures at two tertiary eye care centres in Asia, and to highlight areas where we could better tailor care for patients with ophthalmic conditions in the event of future lockdowns.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted during the initial reopening of outpatient services of two tertiary eye care centres in Asia—one in Singapore and the other in New Delhi, India. These two centres were chosen to represent contrasting perspectives on the impact the pandemic had in two very different countries across Asia. The study period was chosen to be immediately after patients had experienced acute unexpected lockdowns in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Consecutive patients were recruited from both general and specialist outpatient ophthalmology clinics via convenience sampling in the second and third week of June 2020. Each participant self-administered the pen-and-paper questionnaire in the waiting room after verbal informed consent was obtained by research staff. The study protocol was explained to each patient and based on our standardised participant information sheet found on the cover page of the questionnaire (Appendix 1 in the supplementary material). Participation was fully voluntary, all responses were anonymous and no identifiable data was collected. The questionnaire was conducted in English and patients who could understand the language were allowed to self-administer the survey form. In cases where patients could not understand English, the accompanying person or family member could assist to verbally translate the questionnaire into the respective local language that the patient spoke (e.g. Hindi, Tamil, Mandarin, Malay). The inclusion criteria were (1) Patients who have attended outpatient ophthalmological services during the second and third week of June 2020, including repeat visits or first visits; (2) Patients who are able to self-administer and understand the questionnaire, or if unable to for reasons such as poor vision or language barrier, has an accompanying person to assist. The exclusion criteria were (1) Patients who do not agree to participate in the study; (2) Patients who are not present in the outpatient clinics during the study period; (3) Patients who could not understand English and/or have no accompanying persons or family member who could understand English. The target number of patients was 400 but only 326 patients were recruited during the specified study period because of insufficient willing participants. The survey involved a 26-question self-administered form (Appendix 1 in the supplementary material) which collected data on demographics, past ocular history, current treatment and cancelled treatment. Questions on follow-up frequency and number of eye drop medications were designed to elicit the degree of reliance patients had on ophthalmological services and disease burden. The questionnaire also included 12 questions that were designed to elicit patients’ perceptions and experiences on a five-point Likert scale. On analysis of responses to the questionnaire, “agree” and “strongly agree” were determined as positive responses while “disagree” and “strongly disagree” were determined as negative responses to the questions. The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (NHG DSRB Ref. 2020/00384), and waiver of consent was obtained from the ethics committee for all participants.

Results

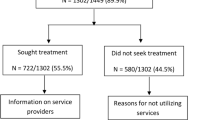

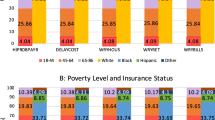

A total of 326 patients were recruited into the study, 200 (200/326, 61.3%) patients from Singapore and 126 (126/326, 38.7%) patients from New Delhi, India. The mean age of patients was 58.2 years (median age of 61 years, SD ± 17.9), with 169 (51.8%) patients being female. The youngest patient was 11 years old and the oldest patient was 93 years old. In terms of laterality, 169 (51.8%) patients had unilateral disease while 146 (44.8%) had bilateral disease, the remaining 11 (3.4%) were unknown. The survey inquired into the number of patients who had experienced cancellations or postponement of appointments. A total of 286 patients (286/326, 88%) of patients responded to this question. We found that a large proportion of patients (151/286, 52.8%) had appointments cancelled during the lockdown period; these appointments included outpatient reviews, surgeries, intravitreal injections and laser procedures. Some patients had more than one such appointment cancelled, resulting in a total of 186 reported cancellations amongst the 151 patients who responded. Cancellation of outpatient consultations (128/186, 68.8%) was the most common, followed by surgeries (19/186, 10.2%), intravitreal injections (25/186, 13.4%) and laser procedures (8/186, 4.3%), the rest were not specified (6/186, 3.2%). Most patients were on at least one eye drop medication (134/326, 41.1%), followed by no eye drop medications (122/326, 37.4%), two eye drop medications (47/326, 14.4%) and lastly three or more eye drop medications (23/326, 7.1%). Follow-up frequency was also recorded and found that the majority of patients recruited (175/326, 53.6%) were required to visit the eye clinic at a frequency shorter than 6-monthly, while patients who required annual follow-up or longer were less likely to be present during the initial reopening phase of outpatient services (55/326, 16.9%) and hence fewer such patients were recruited. Cataract (56/326 17.1%), diabetic retinopathy (34/326, 10.4%) and glaucoma (25/326, 7.7%) were amongst the most common eye conditions. Table 1 describes the demographics of the patients, their follow-up status and treatment received. Table 2 describes the ophthalmic conditions faced by the patients from both centres. Patients from each centre demonstrated distinct responses to the survey and hence results will be reported and compared in the sections below. Survey responses could be broadly classified into four main themes of patients’ perceptions: (1) impact on eye care, (2) access to care, (3) risk of transmission of COVID-19 and (4) non-contact telehealth strategies. Table 3 captures all patients’ responses to the questionnaire. Figure 1 describes the combined responses of patients from both Singapore and India. Figure 2 describes the responses of patients from Singapore while Fig. 3 describes the responses of patients from India.

Patient Population

A total of 200 patients were recruited from the Singaporean centre. The majority of patients were female (126/200, 63.0%). The mean age was 65.7 years (SD ± 13.7 years) and the median age was 67 years old. The youngest patient was 19 years old and the oldest was 93 years old. In terms of laterality, 103 (103/200, 51.5%) patients have unilateral disease while 91 (91/200, 45.5%) had bilateral disease and 6 (6/200, 3.0%) were unknown. A total of 126 patients were recruited from the centre in New Delhi, India. The majority of patients were male (81/126, 64.3%). The mean age was 46.3 years (SD ± 17.4 years) and the median age was 50 years old. Similar in proportion to the Singaporean patients, approximately half (66/126, 52.4%) had unilateral disease while 55 (55/126, 43.7%) had bilateral disease and 5 (5/126, 4.0%) were unknown. In comparison, there were more female patients recruited from the Singaporean centre compared to the Indian centre (63.0% vs 35.7% female). The patients from the Singaporean centre were also older compared to those from the Indian centre (mean age of 65.7 vs 46.3 years).

Baseline Visit Frequency and Medication Burden

A total of 91 (91/200, 45.5%) patients from the Singaporean centre required follow-up frequency shorter than 6 months. This contrasts with patients from the Indian centre who required more frequent follow-ups, with two-thirds (84/126, 66.7%) of patients requiring visits shorter than 6-monthly, out of which 36 (36/126, 28.6%) patients had a visit frequency of at least once a month. Half (100/200, 50.0%) of patients from Singapore were not on any long-term eye drop medications while the other half were on at least one eye drop medication (100/200, 50.0%). As for the Indian centre, most patients were on at least one eye drop medication (104/126, 82.5%) and only a handful were not on any medications (22/126, 17.5%) (Table 1).

Eye Conditions

The two most common eye conditions experienced by patients from the Singaporean centre were cataract (46/200, 23.0%) in the pre- or postoperative stage and glaucoma (or glaucoma suspect) (25/200, 12.5%) (Table 2). As for patients from the Indian centre, the most common eye condition was diabetic retinopathy (26/126, 20.6%), followed by uveitis or ocular inflammatory conditions (11/126, 8.7%). The proportion of retinal and macular conditions seemed to be much higher in patients from the Indian centre (36/126, 28.6%) compared to those from Singapore (14/200, 7.0%) during the study period. More patients from the Singaporean centre presented to the clinic for routine screenings such as plaquenil toxicity, diabetic eye screening, glaucoma suspect screenings and routine eye check-ups. This contrasts with the Indian centre where such visits were absent.

Perceptions on Impact on Eye Care

Patients from India and Singapore had differing perspectives about the impact the pandemic had on their eye health. When asked if COVID-19 had negatively impacted their eye disease, 13.5% (12.5% agree, 1% strongly agree) of patients from the Singaporean centre agreed, whereas a large majority of 61.9% (46.8% agree, 15.1% strongly agree) of patients from the Indian centre agreed. Amongst the patients from Singapore, most felt that their eye conditions were stable (68.5%, 65% agree, 3.5% strongly agree), while only about a third (32.6%, 27% agree, 5.6% strongly agree) of patients from India felt their eye condition was stable.

Patients were also asked about the psychological impact of their eye disease during lockdown, e.g. if they were more distressed by their eye condition compared to regular days, or if it was the most important issue or least of their worries. The majority of patients from India were more distressed as compared to regular days (58.7%, 37.3% agree, 21.4% strongly agree), where 50% (27.8% agree 22.2% strongly agree) felt that their eye disease was the most important issue they faced during the lockdown and 47.6% (34.1% disagree, 13.5% strongly disagree) disagreed that their eye condition was the least of their worries. On the contrary, for patients in Singapore, only 19.5% (17% agree and 2.5% agree) felt more distressed, 31.5% (24.5% agree, 7% strongly agree) felt that their eye condition was the most important issue and 38% (36.5% agree and 1.5% strongly agree) agreed that their eye condition was the least of their worries.

Perceptions on Access to Care

There was a significant difference between patients from each centre in terms of access to care and medications. The majority of patients from the Indian centre were affected such that 70.8% (48.4% agree, 22.2% strongly agree) agreed that they were unable to access the appropriate care for their eye condition, in contrast to only 21.5% (20.5% agree, 1.0% strongly agree) of patients from the Singaporean centre. Similarly, 42.0% (35.7% agree, 6.3% strongly agree) of patients from India were unable to obtain medications, in contrast to only 7% (6.0% agree, 1.0% strongly agree) of patients from Singapore. In addition, patients from India felt more strongly that their eye care centre could have done more for their eye disease during the lockdown, with 50.8% (38.9% agree, 11.9% strongly agree) agreeing, compared to 29% (27.5% agree, 1.5% strongly agree) of patients from Singapore. When asked about reasons for treatment being affected during the lockdown, 72 patients from the Indian centre responded. The most cited reason is the lack of transport (76.4%, 55/72), unavailability of the hospital or healthcare staff (43.1%, 31/126), travel restrictions (6.9%, 5/72) and financial constraints (1.4% 1/72) (Fig. 4).

Perceptions on Risk of Transmission

Risk of exposure to COVID-19 was more of a deterrent to visit eye care centres for patients in India than it was for patients in Singapore. Two-thirds of patients from the Indian centre (66.6%, 45.2% agree, 21.4% strongly agree) were afraid of being infected with COVID-19 if they were to visit the clinic or hospital. As for the Singaporean centre, only 35% (25.5% agree, 9.5% strongly agree) agreed.

Perceptions on Non-contact Telehealth Strategies

Most patients found that the medication delivery service was a convenient way to obtain medications, with 61.1% (50.0% agree, 11.1% strongly agree) of patients from India and 58% (44.5% agree, 13.5% strongly agree) of patients from Singapore who agree. Patients from the Indian centre were more receptive to teleconsultation and non-contact healthcare strategies such that the majority (61.9%, 50.0% agree, 11.9% strongly agree) of patients felt that being able to contact their doctor during the lockdown via teleconsultation could help with their eye condition. On the other hand, more patients from the Singaporean centre disagreed (43.0%, 41.0% disagree, 2.0% strongly disagree) with teleconsultation services than those who agreed (31.0%, 29.5% agree, 1.5% strongly agree).

Discussion

Our survey has explored the impact of the pandemic lockdown measures on patients with ophthalmological conditions and their perceptions regarding eye care during the pandemic. We believe that findings from our study may aid in future pandemic preparedness measures in ophthalmological practice. In general, we found a stark contrast in the perceptions of patients from India and Singapore. Patients from the Indian centre seemed to be more affected by the lockdown, in terms of access to care and disability from their eye conditions. This is likely related to the differences in severity of eye conditions, socio-political and economic climate in the two patient populations. As such, there may not be a “one size fits all” approach in pandemic response. This underscores the importance of early patient involvement and engagement in healthcare decisions and policies as patients’ needs change dynamically.

Impact on Patients’ Eye Care and Access to Care During the Pandemic

Lockdown measures have no doubt affected patients’ access to eye care during the pandemic. Both patient-initiated no-shows and active postponement by eye care institutions contributed to the reduction in elective outpatient attendance. According to a survey by Nair et al. amongst Indian ophthalmologists, there was near total cessation of elective surgeries and ophthalmology practice in 72.5% of respondents during the nationwide lockdown in early 2020 [5]. No-show rates at outpatient ophthalmological services in the Singaporean centre also increased to 33% during the initial lockdown period [4]. Similarly in Hong Kong, elective patient attendance was reduced by 24.6% through active screening and postponement of non-urgent visits [8]. A survey amongst oculoplastic surgeons in the Asia–Pacific also revealed that 85% of them ceased elective lacrimal procedures presumably because of the associated risk of COVID-19 transmission [9]. The results from our survey show similar trends such that half of our survey respondents had experienced cancellations or postponement of appointments. These cancellations included outpatient reviews, surgeries, intravitreal injections and laser procedures. There was also a lack of routine screenings and non-emergent visits especially in the Indian centre. This is evident in the low number of visits for Plaquenil toxicity screening, diabetic eye screening, glaucoma suspect screenings and routine eye check-ups during the study period. This meant that a good number of patients could not obtain the care that they would have if not for the lockdown measures and, as such, it may be worthwhile to explore alternate strategies that may prevent such patients from being lost to follow-up in a pandemic.

Lack of transport was the most cited reason for the inability to obtain the appropriate care for patients from the Indian centre. This is consistent with the fact that transport services were lacking during the lockdown in India [10]. In contrast, Singapore is a small island nation where access to healthcare during the pandemic was logistically easier and transport services were still available during the circuit-breaker. Lack of eye care staff was also another important factor that prevented patients from accessing appropriate eye care. In India, there was significant cessation in ophthalmological services and surgeries [5]. Whilst in the Singaporean centre, 20–30% of manpower from ophthalmological services was redirected to emergency and COVID-19 response [11].

Patients’ Perceived Eye Health and Psychological Impact

Patients' perceived eye health is a product of multiple factors including disease burden and degree of disruption to eye care during the pandemic. Our results show that the majority (61.9%) of patients from the Indian centre felt that COVID-19 had negatively impacted their eye disease, while only a third felt that their eye condition was stable. A large proportion (30–50%) of our patients felt that their eye disease was the most important issue they faced during the lockdown. Patients from the Indian centre seemed to have a higher disease burden as evidenced by the higher medication burden and higher baseline visit frequency which may be indirect indicators of disease burden. They were also of a younger age group and hence sight-threatening complications may have a greater impact on their lifestyle and livelihood. On the other hand, the patient population in Singapore seemed to have less debilitating eye conditions such as cataracts in the pre- or postoperative phase. Only a minority (13.5%) from the Singaporean centre felt that COVID-19 had negatively impacted their eye disease and about half of the patients felt that their eye condition was stable. A similar study on patients’ perceptions of impact on eye health revealed that 47% of patients with age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy were ‘very concerned’ or ‘moderately concerned’ that their eye condition was affected because of missed treatment during the pandemic [12]. This resonates with our patients from the Indian centre as they had more debilitating eye conditions, and a large proportion of patients were unable to obtain their usual eye medications or access the appropriate care needed during the lockdown.

Perceived Risks of Transmission and Aversion to Seeking Eye Care During the Pandemic

Risk of transmission of COVID-19 is potentially high in outpatient ophthalmology practice because of close proximity, multiple tests and long visit duration [8, 13]. A survey conducted in two tertiary eye centres in the USA revealed that fear of COVID-19 exposure was associated with a fourfold increase in the odds of loss to follow-up [12]. Even in life-threatening illnesses, reports have shown that patient reluctance to have direct contact with healthcare workers possibly contributed to delayed presentations [6, 7]. Our study found that our patients’ perceived risk of COVID-19 transmission is potentially higher than that of patients from other parts of the world. A survey conducted in the USA found that only 14% of their patients perceived that routine eye visits were risky [12], whilst in the UK 83.3% of patients were still willing to attend routine visits for cataract surgery [14]. This contrasts with our results where two-thirds of patients from the Indian centre and a third of patients from the Singaporean centre were afraid to come for clinic visits for fear of being exposed to COVID-19. As such, it is useful to elicit patients’ concerns on their particular risk of exposure as it may affect their willingness to seek treatment. Identifying particular patient groups that are more risk-averse to seeking eye care during a pandemic could be a first step, followed by education and reassurance. For example, patients with autoimmune conditions requiring immunosuppression may be at a particularly higher risk of contracting COVID-19. Surveys conducted on patients with rheumatic disease [15] and celiac disease [16] found that the majority were concerned of being at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19. This concern could similarly be present in patients with uveitic conditions requiring immunosuppressive therapy, who may perceive themselves to be at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19. Reassuringly, many retrospective reports on patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy do not show that they are at an increased risk of COVID-19 infection [17]. As such, it is important to identify and address patients’ concerns on their particular risk of exposure through education and reassurance of these more risk-averse groups in order to prevent such patients from being lost to follow-up. In addition, cultural differences in our Asian patients could also have contributed to greater aversion towards COVID-19 transmission as compared to our Western counterparts.

Perceptions on Teleconsultation and Non-contact Strategies During the Pandemic

Receptiveness to telehealth could depend on patients’ age, familiarity with technology and the nature of their eye disease. Our study revealed that patients from the Singaporean centre were less receptive to teleconsultations as compared to those from the Indian centre. The older age group and disease demographic of patients from the Singaporean centre could contributed to this result. A survey on patients from the Singapore Epidemiology of Eye Diseases (SEED) cohort study [18] found that older and lower income patients were less likely to use digital health services. Although most patients view telemedicine as an acceptable alternative to face-to-face consultation, in-person interaction is still preferred under non-pandemic circumstances [19]. A survey done by Sorensen et al. elicited patients’ attitudes toward virtual surgical consultations and revealed that 73% of patients felt it was important that the surgeon examined them prior to the day of surgery [19]. This is especially relevant to our patients from the Singaporean centre where a large majority had cataracts in the perioperative period and might have preferred a face-to-face consultation as compared to a virtual one. As such, teleconsultations may not be the best modality of care for older patients and those requiring surgery during a pandemic.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study presents new data on patients’ perceptions of eye care in two different Asian countries: Singapore and India. We also captured the patients’ perceptions at the initial reopening phase of the eye clinics, where acute disruptions in eye care were recently experienced. A limitation of our study is that minimal medical data was collected as it was a patient-administered survey and no identifiable records were kept. We were hence not able to access medical records retrospectively to detail the eye conditions they were facing. There may also be a selection bias as we have inadvertently excluded all patients who were not physically present at outpatient services. Those who sought consultation at the initial reopening phase could also have faced more pressing eye conditions, hence presenting to the eye clinics earlier despite the pandemic. Our study was also not able to fully capture socio-economic factors that may have affected patients’ perceptions towards eye care during the pandemic.

Strategies for Future Pandemic Response

Our study has identified several concerns faced by patients during the lockdown that may affect their eye care. Infection control strategies are integral to the resumption of ophthalmological services during a pandemic. In addition to that, we have consolidated a few supplementary strategies that may help improve eye care for patients who are at risk of loss to follow-up or have difficulty accessing care during a lockdown. This includes but is not limited to the following patient groups: patients with stable eye diseases; patients who are risk-averse towards transmission of infectious disease; patients who are unfamiliar with technology; and patients who have difficulty attending in-person consultations because of logistical issues e.g. lack of transport services.

Screening and Triaging

Screening and triaging patients prior to cancellation of appointments and procedures could be a safe way to prevent those in need of urgent care from being lost to follow-up. This strategy was adopted in a Hong Kong [8] centre during the lockdown where medical staff rescheduled outpatient appointments on the basis of screening of medical records. This was also done in our Singaporean centre. Identifying patients with more pressing eye diseases can help them in receiving proper care despite the pandemic, and at the same time alleviate healthcare burden by postponing non-urgent appointments. This ensures care is given where it is most needed.

Decentralised Ophthalmic Care and Teleophthalmology

Although it is largely accepted that non-urgent appointments and elective procedures are cancelled during a pandemic, patients with such conditions should not be completely neglected. Whilst tertiary centres may be overburdened by pandemic response, eye care could be decentralised to other institutions such as primary care doctors, optometrists or satellite ophthalmology clinics. Patients with stable eye conditions may also be taught to monitor their eye health through various means especially with the advent of many home monitoring devices such as home tonometers or tablet perimetry applications [20, 21]. Imaging conducted at primary healthcare centres or satellite clinics such as those conducted for diabetic retinopathy screening programmes [22] may be useful to pick up other retinal diseases, although anterior segment assessment may be limited [23]. Leveraging on existing infrastructure may therefore help in screening for eye diseases especially when it cannot be done in a tertiary centre. A study conducted in Pakistan during the pandemic showed that teleconsultation could maintain about a tenth of weekly pre-lockdown ophthalmological services [24]. Indian optometrists also shifted towards teleconsultations during the pandemic [25]. In Singapore, some eye care institutions have adopted a model where community optometrists are empowered to follow up with patients with eye diseases, thereby reducing patient traffic at tertiary eye centres [13]. Our study revealed that there were limited screenings done for Plaquenil toxicity, diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma in the Indian centre during the lockdown. As such, these patients may benefit from routine screening at such satellite clinics with retinal imaging capabilities. In addition, empowering primary care physicians and optometrists to manage general eye conditions may help alleviate patient burden at the tertiary centre.

Improving Access to Medications

Inability to obtain medications is a major issue faced by patients during a lockdown especially if transport services are ceased. Many countries took to instituting delivery services [26,27,28] and this has become a widely accepted practice during the lockdown [29]. Most of the patients in our study agreed that medication delivery is convenient; however, a significant proportion (at least a third) of our patients did not agree. In addition, older patients may still prefer to go to a pharmacy to obtain medications [30]. Elderly patients or those with cognitive impairment may instead benefit from in-person dispensing methods rather than non-contact methods [31]. As such, strategies to improve access to medications need to cater to a wide range of patients. Such strategies may include home delivery [32, 33], medication lockers [34], teleconsultations, or face-to-face dispensing by community pharmacists [35].

Education

A major challenge ahead in pandemic response is catering to a wide variety of patients with differing attitudes and perspectives. Appropriate health-seeking behaviour is important to achieve equity during a pandemic. It is important to find balance between minimising unnecessary visits and ensuring appropriate care for those who need it most. Patients who are averse to attending outpatient visits because of risk of contracting diseases need to be reassured that infection control protocols are sufficient to keep them safe. On the other hand, patients who have stable conditions need to have enough confidence that non-contact strategies and teleophthalmology are sufficiently sophisticated to monitor their eye health. In addition, the elderly population may have difficulties with utilising technology and may prefer face-to-face consultations instead [36]. These patients should receive help to familiarise them with technology, so that they can better access telehealth services in the event of future lockdowns. As such, educational and awareness programmes can help both patients and eye care staff achieve a good balance during a pandemic.

Conclusion

Our patients had varied responses to the survey and differing attitudes towards eye care during the pandemic. As such, there may indeed be a role for individualised and flexible healthcare strategies to meet the needs and preferences of patients. Each country should tailor pandemic response measures to their own population, and this starts with understanding patients’ perceptions and receptiveness to healthcare during the pandemic. This is, however, not just limited to initial pandemic response but also to everyday practice where healthcare providers should aim to strike a balance between safety and efficacy in the mode via which care is provided for patients. As healthcare services evolve during these unprecedented times, patients’ experiences and preferences are crucial in developing methods to adapt to the ‘new normal’. The future of remote healthcare is on the horizon. The lessons learnt from pandemic response can be put into good use beyond COVID-19 and prepare us for when the next wave hits.

References

WHO. WHO Director-General’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020. Accessed 6 Nov 2021.

WHO. Rapid assessment of service delivery for NCDs during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/rapid-assessment-of-service-delivery-for-ncds-during-the-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 16 Jun 2020.

Ministry of Health, Singapore. Circuit breaker to minimise further spread of COVID-19. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/circuit-breaker-to-minimise-further-spread-of-covid-19. Accessed 6 Nov 2021.

Lim LW, Yip LW, Tay HW, et al. Sustainable practice of ophthalmology during COVID-19: challenges and solutions. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(7):1427–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-020-04682-z.

Nair AG, Gandhi RA, Natarajan S. Effect of COVID-19 related lockdown on ophthalmic practice and patient care in India: results of a survey. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(5):725–30. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_797_20.

Schirmer CM, Ringer AJ, Arthur AS, et al. Delayed presentation of acute ischemic strokes during the COVID-19 crisis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2020;12(7):639–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016299.

Tam C-CF, Cheung K-S, Lam S, et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 209 (COVID-19) outbreak on ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction care in Hong Kong China. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13(4):e006631. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006631.

Lai THT, Tang EWH, Chau SKY, Fung KSC, Li KKW. Stepping up infection control measures in ophthalmology during the novel coronavirus outbreak: an experience from Hong Kong. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020;258(5):1049–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-020-04641-8.

Nair AG, Narayanan N, Ali MJ. A survey on the impact of COVID-19 on lacrimal surgery: the Asia–Pacific perspective. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:3789–99. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S279728.

Dore B. COVID-19: collateral damage of lockdown in India. BMJ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1711.

Khor WB, Yip L, Zhao P, et al. Evolving practice patterns in Singapore’s public sector ophthalmology centers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila). 2020;9(4):285. https://doi.org/10.1097/APO.0000000000000306.

Lindeke-Myers A, Zhao PYC, Meyer BI, et al. Patient perceptions of SARS-CoV-2 exposure risk and association with continuity of ophthalmic care. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.0114.

Tham Y-C, Husain R, Teo KYC, et al. New digital models of care in ophthalmology, during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Ophthalmol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317683.

Sii SSZ, Chean CS, Sandland-Taylor LE, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cataract surgery- patients’ perceptions while waiting for cataract surgery and their willingness to attend hospital for cataract surgery during the easing of lockdown period. Eye. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01229-8.

Antony A, Connelly K, De Silva T, et al. Perspectives of patients with rheumatic diseases in the early phase of COVID-19. Arthritis Care Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24347.

Siniscalchi M, Zingone F, Savarino EV, Dodorico A, Ciacci C. COVID-19 pandemic perception in adults with celiac disease: an impulse to implement the use of telemedicine: COVID-19 and CeD. Dig Liver Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2020.05.014.

Thng ZX, De Smet MD, Lee CS, et al. COVID-19 and immunosuppression: a review of current clinical experiences and implications for ophthalmology patients taking immunosuppressive drugs. Br J Ophthalmol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-316586.

Teo CL, Chee ML, Koh KH, et al. COVID-19 awareness, knowledge and perception towards digital health in an urban multi-ethnic Asian population. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90098-6.

Sorensen MJ, Bessen S, Danford J, Fleischer C, Wong SL. Telemedicine for surgical consultations—pandemic response or here to stay?: A report of public perceptions. Ann Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004125.

Kong YXG, He M, Crowston JG, Vingrys AJ. A comparison of perimetric results from a tablet perimeter and humphrey field analyzer in glaucoma patients. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2016;5(6):2–2. https://doi.org/10.1167/tvst.5.6.2.

Gunasekeran DV, Low R, Gunasekeran R, et al. Population eye health education using augmented reality and virtual reality: scalable tools during and beyond COVID-19. BMJ Innov. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjinnov-2020-000522.

Tozer K, Woodward MA, Newman-Casey PA. Telemedicine and diabetic retinopathy: review of published screening programs. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1526/2374-6890/2/4/00131.

Nagra M, Vianya-Estopa M, Wolffsohn JS. Could telehealth help eye care practitioners adapt contact lens services during the COVID-19 pandemic? Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2020;43(3):204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2020.04.002.

Mansoor H, Khan SA, Afghani T, Assir MZ, Ali M, Khan WA. Utility of teleconsultation in accessing eye care in a developing country during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1): e0245343. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245343.

Karthikeyan SK, Nandagopal P, Suganthan RV, Nayak A. Challenges and impact of COVID-19 lockdown on Indian optometry practice: a survey-based study. J Optom. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optom.2020.10.006.

Thong KS, Selvaratanam M, Tan CP, et al. Pharmacy preparedness in handling COVID-19 pandemic: a sharing experience from a Malaysian tertiary hospital. J Pharma Policy Pract. 2021;14(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-021-00343-6.

Ministry of Health, Singapore. Parliamentary QA highlights. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/medication-delivery. Accessed 25 Nov 2021.

Al-Zaidan M, Ibrahim MIM, Al-Kuwari MG, Mohammed AM, Mohammed MN, Al AS. Qatar’s primary health care medication home delivery service: a response toward COVID-19. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:651. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S282079.

Alhamad H, Abu-Farha R, Albahar F, Jaber D. Public perceptions about pharmacists’ role in prescribing, providing education and delivering medications during COVID-19 pandemic era. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(4):e13890. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.13890.

Vordenberg SE, Zikmund-Fisher BJ. Older adults’ strategies for obtaining medication refills in hypothetical scenarios in the face of COVID-19 risk. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2020;60(6):915–922.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2020.06.016.

Taitel M, Jiang J, Rudkin K, Ewing S, Duncan I. The impact of pharmacist face-to-face counseling to improve medication adherence among patients initiating statin therapy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:323–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S29353.

Ministry of Health, Singapore. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/medication-delivery. Accessed 25 Nov 2021.

Tan Tock Seng Hospital. TTSH Medication Delivery Service. https://www.ttsh.com.sg/Patients-and-Visitors/Medical-Services/Pharmacy/Medication-Delivery-Service/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed 25 Nov 2021.

Yeo Y-L, Chang C-T, Chew C-C, Rama S. Contactless medicine lockers in outpatient pharmacy: a safe dispensing system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(5):1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.11.011.

Lim RH, Shalhoub R, Sridharan BK. The experiences of the community pharmacy team in supporting people with dementia and family carers with medication management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1825–1831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.10.005.

Golash V, Athwal S, Khandwala M. Teleophthalmology and COVID-19: the patient perspective. Fut Healthc J. 2021;8(1): e54. https://doi.org/10.7861/fhj.2020-0139.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Rebecca Low, Lee Jia Min, Lai Ser Sei, Andrés Rousselot, Manisha Agarwal and Rupesh Agrawal all made substantial contributions to the study conception and design.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from the National Healthcare Group Domain Specific Review Board (NHG-DSRB), reference number 2020/00384.

Disclosures

Rebecca Low, Lee Jia Min, Lai Ser Sei, Andrés Rousselot, Manisha Agarwal and Rupesh Agrawal all confirm that they have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Data Availability

The original data set was made available to all authors.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Consent for publication: All participants consented to use of data for research and publication purposes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Low, R., Lee, J.M., Lai, S.S. et al. Eye Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Report on Patients’ Perceptions and Experiences, an Asian Perspective. Ophthalmol Ther 11, 403–419 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-021-00444-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-021-00444-0