Abstract

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia is the most common tumour of the ocular surface. It is a spectrum of disease from intraepithelial dysplasia to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Recent years have seen an increase in the use of topical chemotherapeutic agents to treat this condition, often as primary treatment without full-thickness biopsy. This practical approach provides a critical appraisal of the evidence base with the goal being to aid the clinician in the management of these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) is controversial with no consensus as to its optimal management |

Topical chemotherapy agents are now routinely used in many centres as primary treatment for presumed OSSN |

This commentary aims to provide a guide to the clinical management of OSSN lesions |

What was learned from this study? |

Our clinical approach to OSSN lesions is outlined, in particular the importance of obtaining a surgical specimen to direct treatment is emphasized |

Introduction

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) is the most common non-pigmented tumour of the conjunctiva and cornea [1, 2]. Its incidence is 0.5 cases/million/year in the UK [3]. Risk factors for OSSN include smoking, exposure to ultraviolet light and systemic or local immunosuppression, which may be iatrogenic or pathological [4,5,6]. It comprises a spectrum of squamous epithelial change from dysplasia to invasive carcinoma [7, 8]. Its clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and outcomes have been the subject of many review articles [4,5,6,7]. The evidence base is composed of case series, with very few comparator studies and no prospective randomised controlled trials. In addition, there is significant variability in surgical technique (e.g. margin size, cryotherapy location) and chemotherapy regimen (e.g. intralesional versus topical interferon-α2b, mitomycin C strength and regimen) that makes comparing these case series fraught with difficulty. Unsurprisingly, reported recurrence rates vary widely, from 0 to 56% with surgical excision alone [9,10,11,12,13], 0–28% with surgical excision followed by topical interferon-α2b (IFNα2b) [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20], 10–15% with surgical excision followed by topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) [16, 21, 22] and 0–30% with surgical excision followed by topical mitomycin C (MMC) [23,24,25,26,27,28]. From this potpourri of evidence, the clinician must formulate treatment strategies for a diverse patient population, often with many medical comorbidities. This article will outline our approach to the key controversies faced in clinical practice rather than a further summary of the evidence. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Management Issues

Is Biopsy Necessary?

The mainstay for managing OSSN has been wide local excision using a ‘no-touch technique’ with alcohol epitheliectomy if the cornea is involved, and double freeze-thaw cryotherapy to the conjunctival margins [29]. In the past 15 years, there has been a shift to the use of topical chemotherapy, either as primary or neoadjuvant therapy, adjuvant in the presence of positive surgical margins, or for the treatment of recurrent disease [30]. In particular, topical IFNα2b is increasingly favoured owing to its low toxicity and similar rates of OSSN regression and recurrence as surgery [12]. A recent literature-based decision analysis on publications between 1983 and 2015 by Siedlecki et al. found tumour excision with adjuvant topical IFNα2b for management of positive margins to have the lowest rates of persistent or recurrent disease when compared to excision alone, empiric topical IFNα2b or incisional biopsy with adjuvant topical IFNα2b [31]. However, the rates of persistent or recurrent disease in patients treated with excisional biopsy followed by adjuvant topical IFNα2b and those treated with empiric topical IFNα2b were similar [31]. Should we then reserve biopsy for persistent or recurrent disease? To answer this, we need to address the following:

-

1.

Whether histopathological diagnosis alters management of patients

-

2.

Whether there is a difference in the real-world patient experience of these treatments

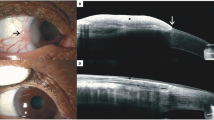

The gold standard to grade OSSN—from conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) through to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)—is histopathological analysis of a full-thickness biopsy [32]. Clinicians have used other techniques in order to avoid performing surgery, which requires a theatre admission. Potential complications of performing a biopsy include limbal stem cell failure (LCSF) if extensive or symblepharon formation with scarring leading to restricted eye movements. Clinical features suggestive of invasive disease are a papillomatous or nodular appearance, but diagnosis based on clinical features alone by experienced clinicians can have an accuracy of only 40% in distinguishing premalignant from invasive disease [7, 33]. Non-invasive pathological assessment consisting of impression or scrape cytology can identify the dysplastic epithelial cells characteristic of OSSN [7, 34,35,36]. Some features on impression cytology are suggestive of invasive disease, such as the presence of syncytial sheaths, macronucleoli and inflammatory cells [7, 21]. But these features are not diagnostic of invasive disease and further investigations are required if they are present. Imaging techniques such as confocal microscopy and high-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography (ASOCT) show promise at delineating the depth of invasion of a lesion [36,37,38]. These techniques are not yet widely used in routine clinical practice. The imaging capability of confocal microscopy is limited by its depth of penetration, which is only up to 1000 μm. In addition, confocal microscopy and ASOCT cannot determine the depth of invasion or distinguish regular conjunctival SCC from mucoepidermoid or spindle cell variants, which are more aggressive with greater rates of intraocular and orbital invasion [39, 40]. Accordingly, it remains that, in order to differentiate premalignant from invasive disease, including the highly malignant variants of SCC, full-thickness biopsy is required.

In addition to the difficulties in determining the grade of an OSSN based on clinical grounds, imaging and non-invasive pathology, it can also be impossible to differentiate tumours of epithelial origin from other forms of conjunctival neoplasms without full-thickness biopsy. The typical features of OSSN are a pale, gelatinous, leukoplakic, telangiectatic mass. Based on clinical appearance, misdiagnosis as OSSN as compared to other non-epithelial lesions can occur in 10.5% of cases [41]. The misdiagnosed lesions are not always benign. Most commonly OSSN can be mistaken for conjunctival melanoma, which requires different treatment, including the use of local radiotherapy. The experience at our centre mirrors this, where in the past year three patients with a pre-biopsy presumptive diagnosis of OSSN were found to have invasive conjunctival melanoma [42]. Without full-thickness biopsy, the clinician and patient accept a small chance that the clinical diagnosis is incorrect, which can result in under- or overtreatment, and the ensuing risks.

SCC of the conjunctiva has been thought to be more frequently locally invasive, rather than prone to metastasis. Large series have found rates of orbital invasion of approximately 10%, often requiring exenteration or modified enucleation, and rates of metastases of less than 1% [43,44,45]. Further, in a series of ten patients with metastatic disease in Saudi Arabia, only one patient died as a result of the disease at a mean follow-up time of 18 months [46]. These studies have been used as evidence that conjunctival SCC is a low-grade malignancy. There is, however, emerging literature that this disease may not be as benign as once thought. A case series of 26 patients with conjunctival SCC from Australia found a death due to metastatic disease rate of 8% [47]. Further, a case series of 1661 patients in the USA found that patients with conjunctival SCC had the same mortality rates as those with conjunctival melanoma, which has a reported tumour-related death rate of up to 24% [48, 49]. If SCC of the conjunctiva is indeed more aggressive than previously thought, early diagnosis is essential.

The treatment of conjunctival SCC is different to premalignant squamous disease. Surgical excision remains the mainstay of treatment for SCC [50, 51].

If the tumour margins are involved after the primary excision, a further wide local excision is often performed. Alternatively, adjuvant topical therapy can be used. Topical MMC 0.04% is the preferred chemotherapeutic agent as SCC does not seem to respond to topical IFNα2b [18]. Similarly, although it may regress in 50% of patients treated with topical 5-FU, it recurs in 75% of these [21]. By contrast, Shields et al. reported a prospective series of patients with conjunctival SCC who demonstrated excellent response to topical MMC 0.04% [23]. In that series, all six patients with SCC (and four with extensive CIN) had complete resolution of disease and no recurrence at a mean follow-up of 22 months. Topical MMC is not, however, the panacea. A different series in the UK reported recurrent disease in two of three patients with conjunctival SCC treated with MMC [24]. It is particularly ineffective if the tumour is thick, or there is orbital extension, presumably due to failure of tissue penetration of topical drops. Radiation therapies have been employed for conjunctival SCC, particularly if scleral invasion is present or the lesion is unable to be surgically excised [7, 52,53,54,55,56,57]. There is, however, emerging evidence that radiotherapy may be a beneficial adjuvant for all patients with conjunctival SCC. Santoni et al. recently published a case series of 54 patients with minimally invasive or invasive SCC diagnosed by excisional biopsy [51]. Adjuvant proton beam radiotherapy (PBRT) was offered to patients with invasive SCC, defined as greater than 0.2 mm invasion of the substantia propria, and not to those with minimally invasive SCC [51]. Adjuvant PBRT was the only factor associated with a lower risk of local recurrence, with a hazard ratio of 0.25, and more patients with minimally invasive SCC had local recurrence than those with invasive SCC, 20% versus 12%, respectively [51]. These are encouraging results and, if validated by future studies, may herald an important role for adjuvant radiotherapy in all patients with conjunctival SCC. Early diagnosis of SCC, rather than a premalignant CIN, by full-thickness biopsy allows the clinician to adopt a more aggressive treatment regimen, which is required to control SCC.

The patient experience of surgical versus medical treatment for OSSN is yet to be examined in detail. Nanji et al. performed a cost analysis in the USA and found that the overall cost of surgical treatment was greater than medical, but that patients who underwent medical treatment had more office visits and more out-of-pocket costs for the IFNα2b drops [58]. A recent quality of life analysis found that surgical patients experience more pain, but less ocular symptoms such as tearing and itchiness [59]. Patients in both groups were highly satisfied with their treatment and functional recovery 1 year after completing it [59]. Those who elected medical management did so frequently because of a fear of surgery [59]. Compliance with prescribed treatment in the real-world setting, outside of clinical trials, is a further issue to consider. This is particularly important, as most patients with OSSN are elderly, often with multiple medical comorbidities, which may influence topical medication compliance especially when the duration of topical treatment (four times a day) may be over a year. Fortunately, intralesional injection of IFNα2b at a concentration of 3 million units/ml may be used to circumvent the issue of likely poor compliance. Flu-like symptoms are a significant side effect of intralesional injection of IFNα2b at this increased concentration; however, from our experience, it appears that both surgical and medical treatment is well tolerated by most patients.

Our preference is for full-thickness biopsy, excisional if possible, because it allows us to accurately establish the diagnosis and appropriately match treatment to the aggressiveness of the disease. Surgical treatment and topical interferon is well tolerated in our institution.

How Should Surgery be Performed?

The gold standard for treatment of OSSN has been surgical excision with no-touch technique, alcohol epitheliectomy and adjuvant cryotherapy to the conjunctival edges [29]. This is our preferred surgical technique. Much lower local recurrence rates have been reported for cryotherapy at the time of excision, such as 7% at 5 years with cryotherapy verses 39% with excision alone [9, 10].

What Local Chemotherapy Agent Should be Used?

In our department, the most common indications for local chemotherapy use are recurrent disease, patient factors that preclude performing excisional biopsy with cryotherapy or as chemoreduction (described below). The available agents are topical or intralesional injection of IFNα2b and topical 5-FU or MMC.

IFNα2b is an endogenous glycoprotein released by various immune cells with antiviral, antibacterial, immunomodulatory and antitumour activity [60]. As topical treatment it is given at a dose of 1 million units/ml qid for a minimum of 3 months and intralesionally at 3 million units/0.5 ml every week for 4–5 weeks [6]. It is the most widely used agent owing to its proven efficacy and limited side effects [12, 15, 61, 62]. It is expensive; a course of topical IFNα2b costs £1440, as compared to £140 for topical 5-FU and £210 for topical MMC, which can limit its use in developing countries.

5-FU is an antimetabolite, a pyrimidine analogue that inhibits thymidylate synthase, and therefore the nucleosides for DNA synthesis [63]. Topically it is given at a concentration of 1% and our preferred regimen is qid for 1 week, then 3 weeks off treatment for four cycles [22]. It must be stored at room temperature, in contrast to IFNα2b drops which must be refrigerated. Patients experience more side effects with this treatment [64, 65], the most common being conjunctival and lid hyperaemia, ocular surface irritation and filamentary keratitis. Occasionally corneal stromal melting has occurred, but we have not noticed this since increasing the interval between treatment cycles from 1 to 3 weeks.

MMC is an alkylating agent that acts in all phases of the cell cycle including RNA and protein synthesis [66]. It can be given at concentrations of 0.02% or 0.04%. In our department, our regimen is MMC 0.04% qid 1 week on, 1 week off for 6 weeks with concurrent dexamethasone 1% qid for the full 6-week duration. Common complications after MMC are keratopathy, ocular irritation and LCSF, although reported rates of long-term complications vary from zero to up to 80% [67, 68].

When Should Chemoreduction be Considered?

Chemoreduction with topical IFNα2b, 5-FU or MMC is an important tool in the armamentarium to treat large OSSN lesions. Our practice is to employ it when the expected morbidity from surgical excision is high; this can be due to extensive limbal disease or diffuse forniceal, tarsal or carcuncular disease. Excessive limbal surgery can lead to LCSF causing corneal conjunctivalisation and scarring. Limbal involvement of an OSSN lesion of greater than 3 or 4 clock hours is an indication for chemoreduction [5, 32]. Kim et al. reported a case series of 18 patients with giant OSSN, classified clinically as at least 6 clock hours of limbal involvement and/or greatest basal diameter at least 15 mm, who were treated with topical or intralesional injection of IFNα2b neoadjuvantally [69]. Thirteen of 18 (72%) patients had complete regression of disease and the remaining five had a 74% reduction in the size of the OSSN allowing adjuvant surgical or laser treatment [69]. A potential alternative to chemoreduction to prevent LCSF is autologous simple limbal epithalial transplant at the time of excisional biopsy. The few reports of this technique have encouraging results [70, 71]. For multifocal or diffuse forniceal, tarsal or carcuncular disease, chemoreduction can shrink these tumours to a size that can be surgically excised, including invasive SCC using topical MMC 0.04% [72]. It is important, however, to rule out orbital invasion of these lesions, which may require more extensive surgery, including modified enucleation or exenteration.

What to do Prior to Intraocular Surgery for a Patient with OSSN?

OSSN is an uncommon condition in the UK [3]. However, if unrecognised, or if there is residual disease after treatment, it can be become invasive to the deeper tissues of the eye via a tract opened by intraocular surgery [73]. Intraocular spread of OSSN can present as a corneal opacity due to invasion of the corneal stroma, an intraocular mass or cells in the aqueous or vitreous. If there is extensive invasion of squamous cell carcinoma, management by lid-sparing exenteration should be considered [73]. If the spread is limited to the cornea, topical chemotherapy or radiotherapy can be attempted.

We recommend all patients who have a prior history of OSSN have mapping biopsies before proceeding to intraocular surgery. If the biopsy is positive, we recommend at least 3 months of topical IFNα2b qid prior to intraocular surgery.

What is the Role of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Classification of Conjunctival Squamous Neoplasia?

The AJCC recently released the revised, 8th edition of the classification of conjunctival squamous neoplasia [74]. The two main features used to define the primary tumour are depth of invasion and the size and extent of involvement of adjoining structures [74]. CIN is classified as Tis and SCC is T1–T4 depending on lesion size (T1, ≤ 5 mm; T2, > 5 mm), invasion of adjoining structures (T3, any structure [cornea, eyelid, sclera] except the orbit; T4, orbital invasion with or without further extension) [74]. To accurately grade a tumour, histopathological evaluation is required. A significant difficulty in interpreting studies that have assessed outcomes based on AJCC grading is that most have based their assessments of AJCC grade on clinical features and not histopathological evaluation [11, 12, 20, 75]. Despite this, in the largest study in which all patients had histopathological evaluation, AJCC grade does appear to be correlated with local recurrence [45]. AJCC grade does not, however, influence initial management and the T3 classification contains a very broad group of tumours, from extension onto the corneal surface, which is unlikely to require any additional treatment, to surgical excision and cryotherapy, through to scleral invasion which often require adjuvant brachytherapy [50]. Future studies are required to better define the role of the AJCC grading of OSSN in clinical practice.

Our Clinical Approach to Suspected OSSN

-

1.

First-line treatment for OSSN: complete excision with double freeze–thaw cryotherapy to conjunctival margins

-

If complete excision is not possible because of disease factors (extent or location) or patient factors, either consider incisional biopsy and adjuvant topical chemotherapy or chemoreduction of the tumour prior to complete excision.

-

-

2.

Adjuvant therapy for OSSN

-

CIN

-

First line: topical IFNα2b 1 million units/ml qid for 3 months minimum [12, 15, 61, 62].

-

Second line: intralesional injection of IFNα2b 3 million units/ml once every week until regression or futility for a maximum of 4–5 injections [17].

-

Third line: topical 5-FU 1% qid 1 week on, 3 weeks off for 16 weeks (four cycles) [22] or topical MMC 0.04% qid 1 week on, 1 week off for 6 weeks (three cycles) [23, 27, 72].

-

-

SCC: topical mitomycin 0.04% qid 1 week on, 1 week off for 6 weeks (three cycles) [23], local radiotherapy with strontium-90 beta application, or ruthenium-106 episcleral plaque [52,53,54,55].

-

Conclusions

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia is an uncommon condition of the ocular surface that can be successfully controlled with surgery and/or topical chemotherapy in the vast majority of patients. This article examines the literature and provides guidance for the clinician managing these patients. Despite the increasing use of topical chemotherapy as primary therapy for this condition, we advocate full-thickness biopsy in order to establish the diagnosis and appropriately pitch the aggressiveness of the adjuvant therapies.

Change history

22 December 2021

The license text was incorrectly structured. The article has been corrected.

References

Shields CL, Demirci H, Karatza E, Shields JA. Clinical survey of 1643 melanocytic and nonmelanocytic conjunctival tumors. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(9):1747–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.02.013.

Shields CL, Alset AE, Boal NS, et al. Conjunctival tumors in 5002 cases. Comparative analysis of benign versus malignant counterparts. The 2016 James D. Allen Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;173:106–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2016.09.034.

Kiire CA, Stewart RMK, Srinivasan S, Heimann H, Kaye SB, Dhillon B. A prospective study of the incidence, associations and outcomes of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in the United Kingdom. Eye Lond Engl. 2019;33(2):283–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-018-0217-x.

Honavar SG, Manjandavida FP. Tumors of the ocular surface: a review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63(3):187–203. https://doi.org/10.4103/0301-4738.156912.

Shields CL, Shields JA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49(1):3–24.

Sayed-Ahmed IO, Palioura S, Galor A, Karp CL. Diagnosis and medical management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Expert Rev Ophthalmol. 2017;12(1):11–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17469899.2017.1263567.

Lee GA, Hirst LW. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39(6):429–50.

Edge SE, Byrd DR, Carducci M, Compton CC, editors. AJCC ophthalmic oncology task force. Carcinoma of the conjunctiva. In: AJC cancer staging manual. 7th edn. New York: Springer; 2009, pp 531–8.

Li AS, Shih CY, Rosen L, Steiner A, Milman T, Udell IJ. Recurrence of ocular surface squamous neoplasia treated with excisional biopsy and cryotherapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;160(2):213–219.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2015.04.027.

Tabin G, Levin S, Snibson G, Loughnan M, Taylor H. Late recurrences and the necessity for long-term follow-up in corneal and conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(3):485–92.

Galor A, Karp CL, Oellers P, et al. Predictors of ocular surface squamous neoplasia recurrence after excisional surgery. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(10):1974–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.04.022.

Nanji AA, Moon CS, Galor A, Sein J, Oellers P, Karp CL. Surgical versus medical treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a comparison of recurrences and complications. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(5):994–1000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.017.

Sturges A, Butt AL, Lai JE, Chodosh J. Topical interferon or surgical excision for the management of primary ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1297–302.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.01.006.

Schechter BA, Koreishi AF, Karp CL, Feuer W. Long-term follow-up of conjunctival and corneal intraepithelial neoplasia treated with topical interferon alfa-2b. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1291–6.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.10.039.

Boehm MD, Huang AJW. Treatment of recurrent corneal and conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia with topical interferon alfa 2b. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(9):1755–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.01.034.

Venkateswaran N, Mercado C, Galor A, Karp CL. Comparison of topical 5-fluorouracil and interferon alfa-2b as primary treatment modalities for ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;199:216–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2018.11.007.

Karp CL, Galor A, Chhabra S, Barnes SD, Alfonso EC. Subconjunctival/perilesional recombinant interferon α2b for ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a 10-year review. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(12):2241–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.052.

Galor A, Karp CL, Chhabra S, Barnes S, Alfonso EC. Topical interferon alpha 2b eye-drops for treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a dose comparison study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(5):551–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2008.153197.

Muñoz de Escalona Rojas JE, García Serrano JL, Cantero Hinojosa J, Padilla Torres JF, Bellido Muñoz RM. Application of interferon alpha 2b in conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia: predictors and prognostic factors. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2014;30(6):489–94. https://doi.org/10.1089/jop.2013.0084.

Shields CL, Kaliki S, Kim HJ, et al. Interferon for ocular surface squamous neoplasia in 81 cases: outcomes based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Cornea. 2013;32(3):248–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182523f61.

Parrozzani R, Frizziero L, Trainiti S, et al. Topical 1% 5-fluoruracil as a sole treatment of corneoconjunctival ocular surface squamous neoplasia: long-term study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(8):1094–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2016-309219.

Joag MG, Sise A, Murillo JC, et al. Topical 5-fluorouracil 1% as primary treatment for ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(7):1442–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.02.034.

Shields CL, Naseripour M, Shields JA. Topical mitomycin C for extensive, recurrent conjunctival-corneal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(5):601–6.

Russell HC, Chadha V, Lockington D, Kemp EG. Topical mitomycin C chemotherapy in the management of ocular surface neoplasia: a 10-year review of treatment outcomes and complications. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(10):1316–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2009.176099.

Daniell M, Maini R, Tole D. Use of mitomycin C in the treatment of corneal conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2002;30(2):94–8.

Ballalai PL, Erwenne CM, Martins MC, Lowen MS, Barros JN. Long-term results of topical mitomycin C 0.02% for primary and recurrent conjunctival-corneal intraepithelial neoplasia. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25(4):296–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/iop.0b013e3181ac4c39.

Gupta A, Muecke J. Treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia with mitomycin C. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(5):555–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2009.168294.

Besley J, Pappalardo J, Lee GA, Hirst LW, Vincent SJ. Risk factors for ocular surface squamous neoplasia recurrence after treatment with topical mitomycin C and interferon alpha-2b. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(2):287–293.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2013.10.012.

Shields JA, Shields CL, De Potter P. Surgical management of conjunctival tumors. The 1994 Lynn B McMahan Lecture. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(6):808–15.

Adler E, Turner JR, Stone DU. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a survey of changes in the standard of care from 2003 to 2012. Cornea. 2013;32(12):1558–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182a6ea6c.

Siedlecki AN, Tapp S, Tosteson ANA, et al. Surgery versus interferon alpha-2b treatment strategies for ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a literature-based decision analysis. Cornea. 2016;35(5):613–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000000766.

Basti S, Macsai MS. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a review. Cornea. 2003;22(7):687–704.

Kao AA, Galor A, Karp CL, Abdelaziz A, Feuer WJ, Dubovy SR. Clinicopathologic correlation of ocular surface squamous neoplasms at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute: 2001 to 2010. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(9):1773–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.049.

Tole DM, McKelvie PA, Daniell M. Reliability of impression cytology for the diagnosis of ocular surface squamous neoplasia employing the Biopore membrane. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(2):154–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.85.2.154.

Nolan GR, Hirst LW, Bancroft BJ. The cytomorphology of ocular surface squamous neoplasia by using impression cytology. Cancer. 2001;93(1):60–7.

Kieval JZ, Karp CL, Abou Shousha M, et al. Ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography for differentiation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia and pterygia. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(3):481–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.08.028.

Thomas BJ, Galor A, Nanji AA, et al. Ultra high-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis and management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ocul Surf. 2014;12(1):46–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2013.11.001.

Parrozzani R, Lazzarini D, Dario A, Midena E. In vivo confocal microscopy of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Eye Lond Engl. 2011;25(4):455–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2011.11.

Cohen BH, Green WR, Iliff NT, Taxy JB, Schwab LT, de la Cruz Z. Spindle cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98(10):1809–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1980.01020040661014.

Rao NA, Font RL. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the conjunctiva: a clinicopathologic study of five cases. Cancer. 1976;38(4):1699–709. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(197610)38:4%3c1699:aid-cncr2820380443%3e3.0.co;2-4.

Rudkin AK, Dodd T, Muecke JS. The differential diagnosis of localised amelanotic limbal lesions: a review of 162 consecutive excisions. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(3):350–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2009.172189.

Gallo B, Thuang C, Arora A, Cohen VML, Damato B, Sagoo MS. Invasive conjunctival malignant melanoma mimicking ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a case series. Paper presented at the OOG Spring Meeting; London; 11–13 Apr 2019.

Cervantes G, Rodríguez AA, Leal AG. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: clinicopathological features in 287 cases. Can J Ophthalmol. 2002;37(1):14–9 (discussion 19–20).

Tunc M, Char D, Crawford B, Miller T. Intraepithelial and invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: analysis of 60 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83(1):98–103.

Yousef YA, Finger PT. Squamous carcinoma and dysplasia of the conjunctiva and cornea: an analysis of 101 cases. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):233–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.08.005.

Tabbara KF, Kersten R, Daouk N, Blodi FC. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 1988;95(3):318–21.

McKelvie PA, Daniell M, McNab A, Loughnan M, Santamaria JD. Squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva: a series of 26 cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(2):168–73. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.86.2.168.

Abt NB, Zhao J, Huang Y, Eghrari AO. Prognostic factors and survival for malignant conjunctival melanoma and squamous cell carcinoma over four decades. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40(4):577–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2019.05.013.

Missotten GS, Keijser S, De Keizer RJW, De Wolff-Rouendaal D. Conjunctival melanoma in the Netherlands: a nationwide study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(1):75–82. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.04-0344.

Bellerive C, Berry JL, Polski A, Singh AD. Conjunctival squamous neoplasia: staging and initial treatment. Cornea. 2018;37(10):1287–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000001651.

Santoni A, Thariat J, Maschi C, et al. Management of invasive squamous cell carcinomas of the conjunctiva. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019;200:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2018.11.024.

Arepalli S, Kaliki S, Shields CL, Emrich J, Komarnicky L, Shields JA. Plaque radiotherapy in the management of scleral-invasive conjunctival squamous cell carcinoma: an analysis of 15 eyes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(6):691–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.86.

Laskar S, Gurram L, Laskar SG, Chaudhari S, Khanna N, Upreti R. Superficial ocular malignancies treated with strontium-90 brachytherapy: long term outcomes. J Contemp Brachytherapy. 2015;7(5):369–73. https://doi.org/10.5114/jcb.2014.55003.

Kenawy N, Garrick A, Heimann H, Coupland SE, Damato BE. Conjunctival squamous cell neoplasia: the Liverpool Ocular Oncology Centre experience. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;253(1):143–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-014-2860-7.

Lecuona K, Stannard C, Hart G, et al. The treatment of carcinoma in situ and squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva with fractionated strontium-90 radiation in a population with a high prevalence of HIV. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(9):1158–61. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306327.

Walsh-Conway N, Conway RM. Plaque brachytherapy for the management of ocular surface malignancies with corneoscleral invasion. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2009;37(6):577–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9071.2009.02092.x.

Graue GF, Tena LB, Finger PT. Electron beam radiation for conjunctival squamous carcinoma. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27(4):277–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/IOP.0b013e31820d872f.

Moon CS, Nanji AA, Galor A, McCollister KE, Karp CL. Surgical versus medical treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a cost comparison. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(3):497–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.10.043.

Mercado CL, Pole C, Wong J, et al. Surgical versus medical treatment for ocular surface squamous neoplasia: a quality of life comparison. Ocul Surf. 2019;17(1):60–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtos.2018.09.001.

Baron S, Tyring SK, Fleischmann WR, et al. The interferons. Mechanisms of action and clinical applications. JAMA. 1991;266(10):1375–83.

Karp CL, Moore JK, Rosa RH. Treatment of conjunctival and corneal intraepithelial neoplasia with topical interferon alpha-2b. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(6):1093–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00577-2.

Schechter BA, Schrier A, Nagler RS, Smith EF, Velasquez GE. Regression of presumed primary conjunctival and corneal intraepithelial neoplasia with topical interferon alpha-2b. Cornea. 2002;21(1):6–11.

Abraham LM, Selva D, Casson R, Leibovitch I. The clinical applications of fluorouracil in ophthalmic practice. Drugs. 2007;67(2):237–55. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200767020-00005.

Rudkin AK, Dempster L, Muecke JS. Management of diffuse ocular surface squamous neoplasia: efficacy and complications of topical chemotherapy. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2015;43(1):20–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/ceo.12377.

Rudkin AK, Muecke JS. Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of localised ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(7):947–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2010.186171.

Abraham LM, Selva D, Casson R, Leibovitch I. Mitomycin: clinical applications in ophthalmic practice. Drugs. 2006;66(3):321–40. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200666030-00005.

Ditta LC, Shildkrot Y, Wilson MW. Outcomes in 15 patients with conjunctival melanoma treated with adjuvant topical mitomycin C: complications and recurrences. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(9):1754–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.01.060.

Khong JJ, Muecke J. Complications of mitomycin C therapy in 100 eyes with ocular surface neoplasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(7):819–22. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2005.086850.

Kim HJ, Shields CL, Shah SU, Kaliki S, Lally SE. Giant ocular surface squamous neoplasia managed with interferon alpha-2b as immunotherapy or immunoreduction. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(5):938–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.11.035.

Mittal V, Narang P, Menon V, Mittal R, Honavar S. Primary simple limbal epithelial transplantation along with excisional biopsy in the management of extensive ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Cornea. 2016;35(12):1650–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000000953.

Kaliki S, Mohammad FA, Tahiliani P, Sangwan VS. Concomitant simple limbal epithelial transplantation after surgical excision of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;174:68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2016.10.021.

Shields CL, Demirci H, Marr BP, Masheyekhi A, Materin M, Shields JA. Chemoreduction with topical mitomycin C prior to resection of extensive squamous cell carcinoma of the conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(1):109–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.123.1.109.

Murillo JC, Galor A, Wu MC, et al. Intracorneal and intraocular invasion of ocular surface squamous neoplasia after intraocular surgery: report of two cases and review of the literature. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2017;3(1):66–72. https://doi.org/10.1159/000450752.

Conway RM, Graue GF, Pelayes D. Conjunctival carcinoma. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual 8th Ed. New York: Springer; 2017.

Singh S, Mohamed A, Kaliki S. Ocular surface squamous neoplasia: analysis based on the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Int Ophthalmol. 2019;39(6):1283–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-018-0943-x.

Acknowledgments

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Victoria Cohen and Roderick O’Day have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10298465.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, V.M.L., O’Day, R.F. Management Issues in Conjunctival Tumours: Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. Ophthalmol Ther 9, 181–190 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-019-00225-w

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40123-019-00225-w