Abstract

Introduction

Fremanezumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting calcitonin gene-related peptide, is indicated for preventive treatment of migraine in adults. Real-world evidence assessing the effect of fremanezumab on migraine-related medication use, health care resource utilization (HCRU), and costs in patient populations with comorbidities, acute medication overuse (AMO), and/or unsatisfactory prior migraine preventive response (UPMPR) is needed.

Methods

Data for this US, retrospective claims analysis were obtained from the Merative® MarketScan® Commercial and supplemental databases. Eligible adults with migraine initiated fremanezumab between 1 September 2018 and 30 June 2019 (date of earliest fremanezumab claim is the index date), had ≥ 12 months of continuous enrollment prior to initiation (preindex period) and ≥ 6 months of data following initiation (postindex period; variable follow-up after 6 months), and had certain preindex migraine comorbidities (depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease), potential AMO, or UPMPR. Changes in migraine-related concomitant acute and preventive medication use, HCRU, and costs were assessed pre- versus postindex.

Results

In total, 3193 patients met the eligibility criteria. From pre- to postindex, mean (SD) per patient per month (PPPM) number of migraine-related acute medication and preventive medication claims (excluding fremanezumab), respectively, decreased from 0.97 (0.90) to 0.86 (0.87) (P < 0.001) and 0.94 (0.74) to 0.81 (0.75) (P < 0.001). Migraine-related outpatient and neurologist office visits, emergency department visits, and other outpatient services PPPM decreased pre- versus postindex (P < 0.001 for all), resulting in a reduction in mean (SD) total health care costs PPPM from US$541 (US$858) to US$490 (US$974) (P = 0.003). Patients showed high adherence and persistence rates, with mean (SD) proportion of days covered of 0.71 (0.29), medication possession ratio of 0.74 (0.31), and persistence duration of 160.3 (33.2) days 6 months postindex.

Conclusions

Patients with certain migraine comorbidities, potential AMO, and/or UPMPR in a real-world setting had reduced migraine-related medication use, HCRU, and costs following initiation of fremanezumab.

Graphical abstract available for this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Fremanezumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that is indicated for the preventive treatment of migraine in adults. |

Real-world evidence on the effect of fremanezumab on migraine-related medication use, health care resource utilization (HCRU), and costs for patients with certain comorbidities, acute medication overuse (AMO), and/or an unsatisfactory prior migraine preventive response is lacking. |

This retrospective claims analysis used data from the Merative® MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters and Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits databases to evaluate changes in migraine-related concomitant acute and preventive medication use, HCRU, and costs pre- and postinitiation of fremanezumab in adult patients with migraine. |

What was learned from the study? |

Patients with certain migraine comorbidities (depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease), potential AMO, and/or an unsatisfactory response to prior migraine preventives in a real-world setting had reduced migraine-related medication use, HCRU, and costs following initiation of fremanezumab treatment. |

Additionally, these patients showed high adherence and persistence rates at > 6 months after fremanezumab initiation. |

These findings extend the existing clinical and real-world evidence in support of fremanezumab treatment for migraine prevention and its effectiveness for patients with migraine alone and those with the selected complications. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including graphical abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25133801.

Introduction

Migraine is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide with an estimated global prevalence of 14% [1] and is associated with a considerable burden on quality of life and daily function [2], as well as a substantial financial burden, with annual total costs estimated at US$27 billion in the USA alone [3]. Despite the availability of a variety of migraine preventive treatment classes, most people with migraine who are eligible for preventive therapy do not use it, and those who do may have unsatisfactory responses to multiple classes due to lack of efficacy and/or tolerability. Migraine has many comorbidities, including depression, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [4,5,6], and some evidence suggests that these can be associated with prior preventive treatment failures [7, 8]. Additionally, some commonly used acute medications, including triptans and dihydroergotamine, are contraindicated for patients with CVD [9], which may make finding a safe, effective treatment more challenging. Patients with more frequent migraine and/or without effective preventive therapy may overuse acute medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), simple analgesics, ergots, triptans, and opioids, for relief during a migraine attack or even preemptively due to anticipatory anxiety of attacks. Overuse of acute medications (AMO) is associated with more frequent migraine attacks, greater disability, and more anxiety [10] and can also lead to medication overuse headache [11, 12]. Patients who attempt sequential preventive treatments face more challenges due to the greater impact of migraine on their activities of daily living and emotional health, which increase further with increasing numbers of headache days, increasing number of prior preventive treatments [7, 13], and more comorbid diseases and conditions [14].

In addition to their clinical implications, comorbidities, AMO, and an unsatisfactory response to prior migraine preventives (URPMP) are associated with increased migraine-related health care resource utilization (HCRU) and costs [4, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Fremanezumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) that potently and selectively targets calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), is approved in the USA for the preventive treatment of episodic migraine (EM) and chronic migraine (CM) in adults and offers patients the choice of quarterly or monthly subcutaneous dosing [25]. Post hoc analyses of the phase 3 HALO CM study have demonstrated the efficacy of fremanezumab as a preventive treatment for CM regardless of the presence of comorbid depression or AMO [10, 26]. A phase 3b clinical trial, the FOCUS study, demonstrated the efficacy and tolerability of fremanezumab in patients with migraine who had multiple previous migraine preventive treatment attempts, based on documented failure [due to lack of efficacy and/or tolerability (as further defined in the study)] to two to four classes of migraine preventive medications [27]. Based on phase 3 efficacy and safety data supporting the use of CGRP or CGRP receptor mAbs (used herein as “CGRP pathway mAbs”) and their ease of use, the European Headache Federation guidelines (2022) stated that there was no reason on clinical grounds not to use CGRP pathway mAbs as a first-line treatment [28].

Recent retrospective chart reviews have demonstrated substantial clinical benefit of fremanezumab for patients with migraine and AMO, major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), or prior migraine preventive treatment failures [29, 30]. Such chart review studies are limited by the data available in the electronic medical record (i.e., HCRU and costs cannot be analyzed). Thus, there is limited real-world evidence (RWE) on the impact of CGRP pathway mAbs on migraine-related HCRU and costs in patient populations with CVD, depression or anxiety, potential AMO, and/or UPMPR. Prescribers and payors may gather insights from RWE that otherwise may not be available in controlled trials. Because of this, real-world data are important to provide the full context of fremanezumab use to help inform and guide prescribers and payors in treatment decisions, thereby enhancing patient care. The purpose of this real-world, retrospective claims analysis was to assess migraine-related medication use, migraine-related HCRU, migraine-related costs, and adherence in patients with certain comorbidities, AMO, or UPMPR during the 6–12 months after initiating first fremanezumab treatment.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

Data for this real-world, retrospective, pre-post claims analysis were drawn from the Merative MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database and the MarketScan Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits Database; permission was obtained to access both databases. The MarketScan Commercial database provides inpatient, outpatient, and outpatient prescription information for employees and their dependents who are covered under managed care health plans, preferred provider organizations (PPO), point of service (POS) plans, indemnity plans, and health maintenance organizations (HMO). The MarketScan Medicare supplemental database provides medical and pharmacy information for retirees with Medicare supplemental insurance provided by employers. The Medicare-covered portion of payment and employer-paid portion are included in the database.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical approval was not required for this study as only existing health care claims were used and therefore the data do not meet the definition of human subject research. As this study did not involve human participants or the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, Institutional Review Board approval was not required. All data recorded on the databases were de-identified and fully compliant with United States patient confidentiality requirements, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996.

Patient Eligibility

Eligible patients included those who were ≥ 18 years of age with greater than or equal to one pharmacy claim for fremanezumab during the identification period (1 September 2018 to 30 June 2019; first fremanezumab initiation date was considered the index date; Fig. 1); greater than or equal to one migraine diagnosis on or 12 months prior to the index date; continuous enrollment in the database ≥ 12 months before the index date (preindex period) and ≥ 6 months after the index date (postindex period), with variable follow-up after 6 months; and evidence of certain migraine comorbidities, potential AMO, or UPMPR during the preindex period. Migraine diagnosis was confirmed using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes G43.xx. For the identification of this population, the selected migraine comorbidities included MDD, GAD, or CVD, which were identified based on greater than or equal to one inpatient or greater than or equal to two outpatient medical claims (≥ 30 days apart) with an ICD-10 diagnosis code for MDD, GAD, or CVD during the 12-month preindex period. Potential AMO was considered as using ≥ 15 pills per month of NSAIDs, acetylsalicylic acid, or paracetamol; or ≥ 10 pills per month of ergots, triptans, nonopioid combination analgesics, opioids, or any combination of acute medications during the 90 days prior to the index date. UPMPR was identified based on claims for greater than or equal to two of migraine preventive medication classes during the 12-month preindex period. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant during the study period or were using a CGRP pathway mAb other than fremanezumab on the index date.

Data were analyzed for the overall eligible population of patients with the selected migraine comorbidities, potential AMO, and UPMPR. Select subgroups of interest within this population with MDD and/or GAD, potential AMO, and prior CGRP receptor-targeted mAb (erenumab) use were analyzed separately. These groups were not mutually exclusive.

Study Outcomes

Data were assessed during a 12-month preindex period and a 6-month postindex period, with 6 months of variable follow-up thereafter (Fig. 1). Data on patient demographic characteristics (subgroup, age, sex, and dosing schedule) were extracted from the databases, along with migraine-related medication use, HCRU, and health care cost data. For migraine-related medication use and associated costs, this analysis evaluated the proportions of patients using individual acute and preventive medications, as well as numbers of acute and preventive medication claims and costs overall. For migraine-related HCRU and costs, this analysis examined numbers and costs for inpatient visits, emergency department (ED) visits, and outpatient visits. Fremanezumab acquisition costs were excluded from this cost analysis due to US payor pricing variability, with pricing often determined by rebates and not wholesale acquisition cost pricing. Patient adherence to fremanezumab was assessed using proportion of days covered (PDC) and medication possession ratio (MPR). PDC was calculated using the number of days covered by fremanezumab divided by a fixed follow-up period of 6 or 12 months. MPR was calculated using the sum of the days’ supply from all index medication prescriptions divided by a fixed follow-up period of 6 or 12 months. Calculations of PDC and MPR at 12 months are based on patients who had ≥ 12 months of follow-up. In addition to the mean PDC and MPR, patients were categorized as adherent or nonadherent based on cutoffs of PDC ≥ 0.80 and MPR ≥ 0.80 [31, 32]; the proportion of adherent patients based on these PDC and MPR cutoffs was summarized over 6 months. Persistence was assessed based on the number of days from the index date until earliest discontinuation of fremanezumab or the end of the follow-up period. Persistence was defined in line with other studies of migraine preventive medications as no treatment gaps ≥ 60 days since the end of the last prescription fill [33, 34].

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized using the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the mean, while categorical outcomes were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Changes in these outcomes from preindex to postindex were summarized using the mean difference and the 95% confidence interval. For HCRU, migraine medication use and health care costs paired t-tests were used for comparisons between the preindex and postindex periods. All costs were adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and standardized to 2019 US dollars. All continuous endpoints were reported per patient per month (PPPM) to account for the variable length of follow-up in the patient population. A McNemar’s chi-square test was used for comparisons of the proportion of patients using acute and preventive medications between the preindex and postindex periods. A P value of < 0.05 for preindex versus postindex was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

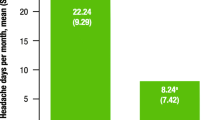

A total of 6082 patients were identified with ≥ 1 claim for fremanezumab between 1 September 2018 and 30 June 2019. Of those identified, 3193 patients met all inclusion criteria (Fig. 2). Baseline and demographic characteristics are summarized for the overall population and subgroups in Table 1. Most patients identified were female [n = 2759 (86.4%)], the mean (SD) age was 45.6 (11.6) years. of the preindex, 1466 patients (45.9%) had CM, 1863 (58.3%) had EM, and 21 (0.7%) had migraine of unidentified type. Most patients had initiated monthly fremanezumab dosing [n = 2761 (86.5%)]. The mean (SD) duration of follow-up among the total patient population was 307.1 (69.2) days. The most common comorbidities were back pain, obesity, neck pain, and hypertension, all reported in ≥ 30% of patients. For the subgroups, 1183 (37.0%) patients had MDD and/or GAD [MDD alone, 350 (11.0%); GAD alone, 468 (14.7%); or MDD and GAD, 365 (11.4%)], 1039 (32.5%) had CVD, 1458 (45.7%) had potential AMO, and 422 (13.2%) had prior erenumab use. Similar proportions of patients had CVD within the MDD and/or GAD [381/1183 (32.2%)], potential AMO [435/1458 (29.8%)], and prior erenumab use [119/422 (28.2%)] subgroups. Baseline characteristics were similar for those subgroups and the overall population, although the mean age was higher among the potential AMO and prior erenumab subgroups (Table 1).

Patient attrition diagram. AMO acute medication overuse, UPMPR unsatisfactory prior migraine preventive response, CGRP calcitonin gene-related peptide, MDD major depressive disorder, GAD generalized anxiety disorder, CVD cardiovascular disease, ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. aSelected comorbidities included MDD, GAD, or CVD and were defined by greater than or equal to one inpatient or greater than or equal to two outpatient medical claims (≥ 30 days apart) with an ICD-10 diagnosis code for MDD, GAD, or CVD during the 12-month preindex period. AMO was defined as ≥ 15 pills per month of paracetamol, NSAIDs, or acetylsalicylic acid; ≥ 10 pills per month of ergots, triptans, nonopioid combination analgesics, or opioids; or ≥ 10 pills per month of any combination of these acute medications. Patients were classified as having an UPMPR if they had claims greater than or equal to two of migraine preventive medication classes during the 12-months preindex

Adherence and Persistence

For assessment of adherence in the overall population, the mean (SD) PDC was 0.71 (0.29) at 6 months after follow-up and 0.58 (0.34) at 12 months after follow-up (in patients with ≥ 12 months of follow-up), and the mean (SD) MPR was 0.74 (0.31) at 6 months and 0.59 (0.35) at 12 months (Fig. 3). Based on a PDC ≥ 80% and MPR ≥ 80%, respectively, 53.6% (1713/3193) and 59.1% (1886/3193) of patients were categorized as adherent at 6 months postindex, and 37.5% (277/3193) and 40.7% (301/3193) of patients were categorized as adherent at 12 months postindex. The mean (SD) persistence duration was 160.3 (33.2) days over 6 months and 251.4 (115.2) days over 12 months, based on a 60-day gap of postindex continuous treatment. Adherence and persistence were comparable with the overall population for patients receiving quarterly and monthly fremanezumab (Table S1), as well as for subgroups of patients with MDD and/or GAD, potential AMO, and prior erenumab use (Fig. 3 and Table S1).

Migraine-Related Acute and Preventive Medication Use

Overall Population

In the overall population, use of migraine-related acute and preventive medications (excluding fremanezumab) decreased from preindex to postindex across all medication types, based on the proportion of patients using individual acute and preventive medications (Fig. 4A and B). Reductions were also observed in the mean number of claims PPPM for migraine-related acute medications [preindex, 0.97 (0.90) versus postindex, 0.86 (0.87); P < 0.001] and migraine preventive medications [excluding fremanezumab; preindex, 0.94 (0.74) versus postindex, 0.81 (0.75); P < 0.001]. Monthly and quarterly dosing of fremanezumab also resulted in reductions in migraine-related acute medication claims PPPM from preindex to postindex [preindex versus postindex: quarterly, 0.97 (0.88) versus 0.82 (0.84); monthly, 0.97 (0.90) versus 0.86 (0.87); both P < 0.001], as well as migraine preventive medication claims [excluding fremanezumab; preindex versus postindex: quarterly, 0.87 (0.71) versus 0.74 (0.73); monthly, 0.95 (0.74) versus 0.82 (0.75); both P < 0.001]. The proportion of patients using specific acute medications in the quarterly fremanezumab dose group decreased as follows from preindex to postindex: triptans, 65.1% (281/432) versus 57.6% (249/432; P = 0.165); NSAIDs, 57.2% (247/432) versus 46.5% (201/432; P = 0.030); opioids (including combinations), 54.9% (237/432) versus 45.8% (198/432; P = 0.061); and butalbital combinations, 26.2% (113/432) versus 18.1% (78/432; P = 0.011). Similar decreases were observed with monthly dosing: triptans, 66.6% (1840/2761) versus 58.0% (1601/2761; P < 0.001); NSAIDs, 56.0% (1546/2761) versus 46.5% (1283/2761; P < 0.001); opioids, 54.4% (1,502/2,761) versus 49.6% (1368/2761; P = 0.012); and butalbital combinations, 22.8% (630/2761) versus 16.8% (464/2761; P < 0.001). Reductions were also observed in the proportion of patients using migraine preventive medications from preindex to postindex with quarterly fremanezumab [antiepileptics, 62.5% (270/432) versus 50.0% (216/432); antidepressants, 50.0% (216/432) versus 39.6% (171/432); antihypertensives, 40.7% (176/432) versus 31.9% (138/432); onabotulinumtoxinA, 32.4% (140/432) versus 23.8% (103/432); all P ≤ 0.032] and monthly fremanezumab [antiepileptics, 64.6% (1784/2761) versus 51.2% (1414/2761); antidepressants, 51.1% (1410/2761) versus 41.4% (1144/2761); antihypertensives, 40.6% (1122/2761) versus 34.0% (938/2761); onabotulinumtoxinA, 30.5% (842/2761) versus 25.0% (691/2761); all P < 0.001].

Proportion of patients using individual A acute medicationsa and B preventive medicationsb in the overall population and subgroups. NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, MDD major depressive disorder, GAD generalized anxiety disorder, AMO acute medication overuse. a < 6% of patients were using the following acute medications preindex: ergots, paracetamol, and nonopioid combination analgesics. b < 5% of patients were using antihistamines preindex. cIncluding acetylsalicylic acid. dIncluding combinations; preindex versus postindex: strong opioids: overall population, 42.7% versus 37.5% (P = 0.001), AMO subgroup, 55.8% versus 50.6% (P = 0.054), prior erenumab exposure subgroup, 43.6% versus 38.4% (P = 0.237); weak opioids: overall population, 27.8% versus 23.4% (P < 0.001), AMO subgroup, 38.6% versus 30.7% (P < 0.001), prior erenumab exposure subgroup, 23.7% versus 23.7% (P = 1.000). eAntiepileptics and anticonvulsants. fAntihypertensives, antianginals, antiarrhythmics, and alpha agonists

MDD and/or GAD

In the subgroup with MDD and/or GAD (n = 1183), the proportion of patients using migraine-related acute medications decreased across all individual treatments from the preindex to the postindex period, as did the proportion of patients using migraine preventive medications (Fig. 4A and B). The mean (SD) number of claims PPPM preindex versus postindex decreased from 0.98 (0.91) versus 0.89 (0.92) for acute medications and from 1.05 (0.82) versus 0.92 (0.82) for preventive medications (both P < 0.001).

Potential AMO

The subgroup of patients with potential AMO (n = 1458) also showed reductions in migraine-related acute and preventive medication use. The proportion of patients using migraine-related acute medications decreased across all individual treatments in the postindex compared with the preindex period; the proportion of patients using individual migraine preventive medications also showed a statistically significant decrease (Fig. 4A and B). The mean (SD) number of acute medication claims PPPM was 1.50 (0.99) preindex versus 1.33 (0.98) postindex, and the mean (SD) number of preventive medication claims PPPM was 0.93 (0.79) preindex versus 0.84 (0.79) postindex (both P < 0.001).

Prior Erenumab Use

In the subgroup of patients who had previously used erenumab for migraine preventive treatment (n = 422), the proportion of patients using individual acute and preventive medications also decreased across all treatments from the preindex compared with the postindex period (Fig. 4A and B). Migraine-related acute and preventive medication claims also decreased in this subgroup. The mean (SD) number of acute medication claims PPPM was 1.15 (0.97) preindex versus 1.03 (0.96) postindex; the mean (SD) number of preventive medication claims PPPM was 1.20 (0.78) preindex versus 0.91 (0.76) postindex (both P < 0.001).

Migraine-Related HCRU

Overall Population

Compared with the 12-month preindex period, this study showed that migraine-related HCRU PPPM generally decreased slightly or remained stable in the overall population 6 months after fremanezumab initiation (Fig. 5A). From preindex to postindex, statistically significant reductions were observed in the mean (SD) number of overall outpatient visits PPPM [0.35 (0.31) versus 0.32 (0.35); P < 0.001], outpatient neurologist visits PPPM [0.15 (0.18) preindex versus 0.14 (0.17); P < 0.001], and other outpatient services (e.g., laboratory assessments, radiology, or administration of medication in office) PPPM [0.30 (0.51) versus 0.26 (0.53); P < 0.001]. Mean (SD) ED visits PPPM remained relatively stable from the pre- to the postindex period, although the difference was statistically significant due to the high variability of the dataset (P = 0.009). In the quarterly and monthly dosing subgroups, changes in HCRU were comparable with the overall population.

MDD and/or GAD

Like the overall population, patients with MDD and/or GAD demonstrated a decrease or remained stable for migraine-related HCRU PPPM after initiating fremanezumab treatment (Fig. 5B). The mean number of outpatient visits, outpatient neurologist visits, and other outpatient services PPPM decreased from the preindex period to the postindex period (all P ≤ 0.003). Mean emergency department (ED) visits PPPM remained stable from the preindex to the postindex period.

Potential AMO

Patients identified with potential AMO also demonstrated a decrease in migraine-related HCRU PPPM after initiating fremanezumab treatment, although the differences were not statistically significant in most studied outpatient settings (Fig. 5C). The mean number of general outpatient office visits decreased from the preindex to the postindex period (P = 0.013). The mean number of ED visits was relatively stable in the preindex compared with the postindex period, as was the mean number of neurologist visits and other outpatient-related services.

Prior Erenumab Use

Patients who had prior erenumab exposure showed statistically significant reductions in migraine-related HCRU PPPM in various outpatient settings after initiating fremanezumab, including the number of outpatient visits overall, outpatient neurologist visits, and other outpatient services (all P ≤ 0.003; Fig. 5D). The mean (SD) number of ED visits did not change from preindex [0.03 (0.10)] to post-index [0.04 (0.18); P = 0.294].

Migraine-Related Health Care Costs

Overall Population

Compared with the 12-month preindex period, migraine-related acute medication and nonfremanezumab preventive medication costs demonstrated statistically significant decreases between the pre- and postindex periods (Fig. 6). Mean (SD) acute medication costs PPPM [in US dollars (USD)] decreased from US$93 (US$224) preindex to US$74 (US$219) postindex (P < 0.001). Mean (SD) preventive medication costs (excluding fremanezumab) also decreased from preindex [US$202 (US$297)] to postindex [US$186 (US$307); P < 0.001]. Similarly, migraine-related health care costs showed decreases. Mean (SD) total migraine-related health care costs PPPM (excluding fremanezumab) decreased from US$541 (US$858) preindex to US$490 (US$974) postindex (mean difference, US$51; P = 0.003; Fig. 7). For individual migraine-related health care costs, migraine-related outpatient office costs decreased from preindex [mean (SD), US$46 (US$46)] to postindex [US$38 (US$45)], as did migraine-related outpatient neurologist costs [US$21 (US$28) versus US$17 (US$24); both P < 0.001; Table S2]. Mean ED and outpatient costs decreased numerically from preindex to postindex, but the changes were not statistically significant (Table S2).

Migraine-related A acute and B preventivea medication costs PPPM in overall patients, and those with MDD and/or GAD, potential AMO, or prior erenumab use. PPPM per patient per month, USD US dollars, MDD major depressive disorder, GAD generalized anxiety disorder, AMO acute medication overuse. aPreventive medication costs excluding fremanezumab

MDD and/or GAD

In the subgroup with MDD and/or GAD, mean (SD) migraine-related acute migraine costs decreased from US$96 (US$242) preindex to US$75 (US$220) postindex (P < 0.001; Fig. 6). Mean (SD) preventive medication costs (excluding fremanezumab) did not show a statistically significant change: US$212 (US$317) preindex to US$198 (US$334) postindex (P = 0.071; Fig. 6). Mean overall health care costs decreased numerically from preindex to postindex (mean difference, US$45), although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.109; Fig. 7). Mean (SD) ED costs and other outpatient-related costs remained relatively constant from preindex to postindex (Table S2). Migraine-related overall outpatient costs and outpatient neurologist costs decreased from preindex to postindex (both P < 0.001; Table S2).

Potential AMO

The subgroup with potential AMO demonstrated similar results to the overall population.

Mean (SD) migraine-related acute medication costs decreased from US$139 (US$287) preindex to US$114 (US$287) postindex (P < 0.001; Fig. 6). Mean (SD) preventive medication costs (excluding fremanezumab) also decreased numerically, although not statistically significantly, from US$202 (US$295) preindex to US$192 (US$310) postindex (P = 0.125; Fig. 6). Overall health care costs showed a nonstatistically significant decrease from preindex to postindex (mean difference, US$41; P = 0.156; Fig. 7). For overall outpatient costs and costs related to outpatient neurologist visits, decreases were observed from preindex to postindex (both P < 0.001; Table S2). Mean (SD) ED costs and costs for other outpatient-related services showed slight, nonstatistically significant decreases from preindex to postindex (Table S2).

Prior Erenumab Use

In this subgroup with prior erenumab use, mean (SD) migraine-related acute medication costs decreased from preindex [US$143 (US$327)] to postindex [US$126 (US$325)], but the changes were not statistically significant (P = 0.061; Fig. 6). Mean (SD) preventive medication costs (excluding fremanezumab) demonstrated a reduction from US$433 (US$391) preindex to US$282 (US$399) postindex (P < 0.001; Fig. 6). Overall health care costs decreased from preindex to postindex (mean change, US$189; P = 0.001; Fig. 7). Mean overall outpatient costs and costs related to outpatient neurologist visits decreased from preindex to postindex (both P < 0.001; Table S2). No statistically significant differences were observed in mean (SD) ED costs, inpatient admission costs, or other outpatient costs from preindex to postindex (Table S2).

Discussion

In this real-world study, patients with migraine and the selected comorbidities, potential AMO, and/or UPMPR who received fremanezumab had reductions in the use of migraine-related acute and preventive medications and incurrence of less migraine-related HCRU and costs. Moreover, high adherence and persistence rates were observed > 6 months after initiating fremanezumab treatment, even in subgroups with MDD/GAD, potential AMO, and/or previous erenumab use. Comparable reductions in migraine-related acute and preventive medication use, HCRU, and health care costs were observed among the subgroups of patients with MDD and/or GAD, potential AMO, and prior erenumab use. There has been a longstanding belief that patients with psychiatric comorbidities may not achieve equal benefits or adhere to preventive migraine treatments, although the evidence to support this belief is mixed [7, 8]. The current findings show that patients with GAD, as well as CVD, can achieve benefits from preventive therapies. For this patient population, reductions in migraine-related acute and preventive medication use other than fremanezumab may represent improved management of migraine symptoms and their associated burden without excess additional medication, reducing the potential risks, costs, and side effects associated with polypharmacy [35, 36]. Reduced use of migraine-related acute medications, in particular, could render patients less susceptible to develop AMO or allow patients to revert from AMO, therefore lowering their risk for medication overuse headache (MOH) [37]. The reductions observed across subgroups in migraine-related HCRU, though modest, further demonstrate amelioration of migraine-related burden for this patient population, as patients on average required fewer outpatient, ED, and neurologist office visits with fremanezumab treatment. Patients with migraine typically have greater utilization of outpatient health care resources compared with inpatient or ED visits [38,39,40,41]; the statistically significant reductions in outpatient HCRU observed in the current study may result in reduced stress on the health care system and greater availability of resources for additional patients awaiting diagnosis and treatment.

Prior studies have demonstrated the real-world clinical benefit of fremanezumab for patients within this patient population. Driessen et al. found that fremanezumab treatment demonstrated sustained reductions in monthly migraine days over 6 months in a subgroup of patients with MDD or GAD, a subgroup with AMO, and subgroups with an unsatisfactory response to multiple migraine preventive treatments in a retrospective online, clinician panel-based chart review [29, 30]. The current study expands upon those findings to demonstrate reductions in migraine-related acute and preventive migraine medication use and migraine-related inpatient and outpatient office visits, as would be expected to follow with reductions in migraine symptoms. Associated reductions in migraine-related health care costs were modest due to low baseline values and the relatively low costs of migraine-related medications in comparison with the drug acquisition costs of fremanezumab; nonetheless, these results were statistically significant when the costs of fremanezumab itself were excluded from the analyses. Clinical and health-related quality of life outcomes are key attributes of value to not only patients but payors as well [42]; improvement in those outcomes may also contribute to reduced absenteeism and improved productivity that could lead to reductions in the indirect costs of migraine [43]. Despite the modest magnitude of the reductions in migraine-related HCRU and costs observed here, these findings alongside the previously demonstrated clinical and real-world benefit of fremanezumab supports its overall value.

Historically, adherence and persistence to traditional oral migraine preventive medications have been low, and those low adherence rates may contribute to poor clinical outcomes and high health care costs [44]. Effectiveness of migraine medication has been shown to impact patient adherence [45]. In the current study, patients initiating fremanezumab demonstrated adherence and persistence rates at 6 months (adherence: PDC ≥ 0.80, 53.6%; MPR ≥ 0.80, 59.1%; persistence: 67.9%) that are comparable with those reported in other, similar studies, despite the complicating clinical factors for these migraine patients, including the presence of comorbidities, potential AMO, and UPMPR. A claims analysis using IQVIA databases found that for patients initiating erenumab, 30.8% of patients had a PDC ≥ 0.80, 41.7% had an MPR ≥ 0.80, and 58.5% were persistent after 6 months [34]. Another study of patients initiating erenumab identified in the Merative MarketScan Database found that 47.3% of patients were persistent after 6 months of follow-up; however, that study used a 45-day gap as opposed to the 60-day gap used in the current study [46]. In a chart review of patients initiating erenumab within 11 months postapproval, the average PDC at 6 months was 79% [47]; here the average PDC at 6 months was 71% for the overall population.

Among patients with continuous enrollment ≥ 12 months postindex, 37.5% of patients had a PDC ≥ 0.80, 40.7% had an MPR ≥ 0.80, and 42.9% were persistent. These findings are comparable with a different Merative MarketScan claims analysis in which patients using a CGRP pathway mAb (erenumab, fremanezumab, or galcanezumab) had superior adherence and persistence than those receiving standard of care preventive treatment; 32.7% of patients had a PDC ≥ 80%, 36.7% had an MPR ≥ 80%, and 41.2% of patients were persistent based on a 60-day gap after 12 months of treatment [48]. In the same study, patients using galcanezumab had slightly better adherence and persistence rates (PDC ≥ 80%, 44.2%; MPR ≥ 80%, 48.7%; persistence, 56.8%) [48].

Quarterly and monthly fremanezumab showed comparable effectiveness in reducing migraine-related HCRU and costs, as well as comparable adherence and persistence, in the current study. Patients have previously reported a preference for quarterly fremanezumab dosing [49], and nearly half of clinicians in recent German and UK studies preferred quarterly fremanezumab dosing [50, 51].

This retrospective claims analysis has several strengths in its methodology. Using real-world data allows for insights into the clinical use of fremanezumab in patients with migraine. Further, the claims data used in this analysis provide migraine-related HCRU and costs, which are not available in clinical studies. Moreover, the large sample size allowed for a broader and more diverse study population and provided sufficient data for multiple subgroup analyses, which permit the assessment of different migraine patient populations with treatment challenges. The duration of follow-up (> 300 days on average) is an additional strength of this study; most comparable real-world claims analyses are limited to 3 or 6 months of follow-up.

This real-world study was also subject to certain limitations. The identifying criteria used for the patient subgroup analyzed within this study were inherently limited to the data accessible in the Merative MarketScan databases. Presence of the selected comorbidities (MDD, GAD, or CVD) was evaluated based on ICD-10 diagnosis codes on inpatient and outpatient claims during the 12-month preindex period. Patients were classified as having UPMPR if they had claims greater than or equal to two of migraine preventive medication classes during the 12-months preindex. Potential AMO was defined as ≥ 15 pills per month of paracetamol, NSAIDs, or acetylsalicylic acid; ≥ 10 pills per month of ergots, triptans, nonopioid combination analgesics, or opioids; or ≥ 10 pills per month of any combination of these acute medications; these cutoffs are based on thresholds used in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version) (ICHD-3) for the diagnosis of MOH [52]. While the ICHD-3 classifies AMO as at least 10 or 15 days per month with acute medication use, depending on the medication, these data were not captured in the database. Therefore, the definition of AMO used here focused on the number of pills taken per month.

More or less stringent identification criteria may have impacted the results of these analyses; additionally, this classification does not identify whether these medications are being used to treat migraine or another diagnosis. Nevertheless, the treatment benefits identified here were observed in a patient population whose migraine may be relatively more challenging to treat effectively.

This study was limited to patients with commercial health care coverage or Medicare supplemental insurance, which excludes patients with Medicaid or no insurance coverage and reflected a relatively higher proportion of patients from the southern USA. These claims data do not provide information on disease severity, pain intensity, or duration of symptoms, which can provide valuable insights into medication use, adherence, and persistence data. Finally, claims data do not capture the reasons that patients discontinue prior treatments. Patients may choose to discontinue medications due to poor tolerability or poor response; however, they may also switch due to changes in reimbursement criteria or drug availability. Inability to differentiate between these circumstances using claims data could affect the interpretation of the discontinuation rate.

Conclusions

The results of this study showed decreased migraine-related medication use, migraine-related HCRU, and costs in patients with selected comorbidities, potential AMO, or UPMPR. Additionally, patients showed high adherence and persistence rates at > 6 months after fremanezumab initiation. These findings extend the existing clinical and RWE in support of fremanezumab treatment for migraine prevention and its effectiveness for patients with migraine with or without the selected comorbidities.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the MarketScan Commercial and Claims and Medicare databases; however, restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study and therefore are not publicly available. Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission, including appropriate data use agreements and potential licenses, of the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Medicare databases.

References

Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Linde M, et al. The global prevalence of headache: an update, with analysis of the influences of methodological factors on prevalence estimates. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):34.

GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954–76.

American Headache Society. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59(1):1–18.

Buse DC, Reed ML, Fanning KM, et al. Comorbid and co-occurring conditions in migraine and associated risk of increasing headache pain intensity and headache frequency: results of the migraine in America symptoms and treatment (MAST) study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):23.

Alwhaibi M, Alhawassi TM. Humanistic and economic burden of depression and anxiety among adults with migraine: a systematic review. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37(11):1146–59.

Caponnetto V, Deodato M, Robotti M, et al. Comorbidities of primary headache disorders: a literature review with meta-analysis. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):71.

Pozo-Rosich P, Lucas C, Watson DPB, et al. Burden of migraine in patients with preventive treatment failure attending European headache specialist centers: real-world evidence from the BECOME study. Pain Ther. 2021;10(2):1691–708.

Seng EK, Holroyd KA. Psychiatric comorbidity and response to preventative therapy in the treatment of severe migraine trial. Cephalalgia. 2012;32(5):390–400.

Dodick DW, Shewale AS, Lipton RB, et al. Migraine patients with cardiovascular disease and contraindications: an analysis of real-world claims data. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720963680.

Silberstein SD, Cohen JM, Seminerio MJ, et al. The impact of fremanezumab on medication overuse in patients with chronic migraine: subgroup analysis of the HALO CM study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):114.

Lipton RB, Turner I, Cohen JM, et al. Long-term impact of fremanezumab on response rate, acute headache medication use, and disability in episodic migraine patients with acute medication overuse at baseline: results of a 1-year study. 2019: Presented at: The American Headache Society 61st Annual Scientific Meeting; July 11–14, 2019; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Brandes JL, Kudrow D, Yeung PP, et al. Effects of fremanezumab on the use of acute headache medication and associated symptoms of migraine in patients with episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(5):470–7.

Martelletti P, Schwedt TJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. My Migraine Voice survey: a global study of disease burden among individuals with migraine for whom preventive treatments have failed. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):115.

Foster SA, Hoyt M, Ye W, et al. Direct cost and healthcare resource utilization of patients with migraine before treatment initiation with calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies by the number of prior preventive migraine medication classes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2021.2003127.

Wu J, Davis-Ajami ML, Kevin Lu Z. Impact of depression on health and medical care utilization and expenses in US adults with migraine: a retrospective cross sectional study. Headache. 2016;56(7):1147–60.

Alwhaibi M, Meraya AM, AlRuthia Y. Healthcare expenditures associated with comorbid anxiety and depression among adults with migraine. Front Neurol. 2021;12:658697.

Buse DC, Yugrakh MS, Lee LK, et al. Burden of illness among people with migraine and ≥ 4 monthly headache days while using acute and/or preventive prescription medications for migraine. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(10):1334–43.

Lipton RB, Seng EK, Chu MK, et al. The effect of psychiatric comorbidities on headache-related disability in migraine: results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache. 2020;60(8):1683–96.

Schwedt TJ, Buse DC, Argoff CE, et al. Medication overuse and headache burden: results from the CaMEO study. Neurol Clin Pract. 2021;11(3):216–26.

Bonafede M, Cai Q, Cappell K, et al. Factors associated with direct health care costs among patients with migraine. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(11):1169–76.

Ashina M, Cohen JM, Galic M, et al. Efficacy and safety of fremanezumab in patients with episodic and chronic migraine with documented inadequate response to 2 to 4 classes of migraine preventive medications over 6 months of treatment in the phase 3b FOCUS study. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):68.

Newman L, Vo P, Zhou L, et al. Health care utilization and costs in patients with migraine who have failed previous preventive treatments. Neurology. 2021;11(3):206–15.

Ford JH, Schroeder K, Nyhuis AW, et al. Cycling through migraine preventive treatments: implications for all-cause total direct costs and disease-specific costs. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(1):46–59.

Lipton RB, Cohen JM, Bibeau K, et al. Reversion from chronic migraine to episodic migraine in patients treated with fremanezumab: post hoc analysis from HALO CM study. Headache. 2020;60(10):2444–53.

AJOVY. AJOVY® (fremanezumab-vfrm) [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Teva Pharmaceuticals. 2022.

Lipton RB, Cohen JM, Galic M, et al. Effects of fremanezumab in patients with chronic migraine and comorbid depression: subgroup analysis of the randomized HALO CM study. Headache. 2021;61(4):662–72.

Ferrari MD, Diener HC, Ning X, et al. Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10203):1030–40.

Sacco S, Amin FM, Ashina M, et al. European Headache Federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene related peptide pathway for migraine prevention—2022 update. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):67.

Driessen MT, Cohen JM, Patterson-Lomba O, et al. Real-world effectiveness of fremanezumab in migraine patients initiating treatment in the United States: results from a retrospective chart study. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):47.

Driessen MT, Cohen JM, Thompson SF, et al. Real-world effectiveness of fremanezumab treatment for patients with episodic and chronic migraine or difficult-to-treat migraine. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):56.

Prieto-Merino D, Mulick A, Armstrong C, et al. Estimating proportion of days covered (PDC) using real-world online medicine suppliers’ datasets. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2021;14(1):113.

Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11(1):44–7.

Foster SA, Manjelievskaia J, Ford JH, et al. Adherence and persistence associated with calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) compared to non-CGRP mAb treatments for prevention of migraine. 2021: Poster presented at: American Headache Society Annual Meeting; June 3–6, 2021; virtual 2021.

Hines DM, Shah S, Multani JK, et al. Erenumab patient characteristics, medication adherence, and treatment patterns in the United States. Headache. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14068.

D’Amico D, Sansone E, Grazzi L, et al. Multimorbidity in patients with chronic migraine and medication overuse headache. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;138(6):515–22.

Alex A, Armand CE. Rational polypharmacy for migraine. Pract Neurol. 2022;30–4.

Diener HC, Holle D, Solbach K, et al. Medication-overuse headache: risk factors, pathophysiology and management. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(10):575–83.

Tepper SJ, Fang J, Vo P, et al. Impact of erenumab on acute medication usage and health care resource utilization among migraine patients: a US claims database study. J Headache Pain. 2021;22(1):27.

Ford JH, Foster SA, Stauffer VL, et al. Patient satisfaction, health care resource utilization, and acute headache medication use with galcanezumab: results from a 12-month open-label study in patients with migraine. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2018;12:2413–24.

Sumelahti ML, Sumanen M, Sumanen MS, et al. My Migraine Voice survey: disease impact on healthcare resource utilization, personal and working life in Finland. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):118.

Ambrosini A, Estemalik E, Pascual J, et al. Changes in acute headache medication use and health care resource utilization: Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating galcanezumab in adults with treatment-resistant migraine (CONQUER). J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(6):645–56.

Saldarriaga EM, Hauber B, Carlson JJ, et al. Assessing payers’ preferences for real-world evidence in the United States: a discrete choice experiment. Value Health. 2022;25(3):443–50.

Lipton RB, Lee L, Saikali NP, et al. Effect of headache-free days on disability, productivity, quality of life, and costs among individuals with migraine. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(10):1344–52.

Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF. Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(1):22–33.

Kardas P, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M. Determinants of patient adherence: a review of systematic reviews. Front Pharmacol. 2013;4:91.

Chandler D, Szekely C, Aggarwal S, et al. Migraine characteristics, comorbidities, healthcare resource utilization, and associated costs of early users of erenumab in the USA: a retrospective cohort study using administrative claims data. Pain Ther. 2021;10(2):1551–66.

Bogdanov A, Chia V, Bensink M, et al. Early use of erenumab in US real-world practice. Cephalalgia Reports. 2021;4:251581632110204.

Varnado OJ, Manjelievskaia J, Ye W, et al. Treatment patterns for calcitonin gene-related peptide monoclonal antibodies including galcanezumab versus conventional preventive treatments for migraine: a retrospective US claims study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:821–39.

Buse DC, Gandhi SK, Cohen JM, et al. Improvements across a range of patient-reported domains with fremanezumab treatment: results from a patient survey study. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):109.

Heinze A, Totev TI, Krasenbaum LJ, et al. Real-world reductions in migraine and headache days for patients with migraine initiating fremanezumab in Germany. Presented at: 8th Annual European Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting; 25–28 June 2022; Vienna, Austria.

Afridi S, Totev TI, Krasenbaum LJ et al. Real-world reductions in monthly migraine days and migraine-related health care resource utilization in UK patients with migraine who initiated fremanezumab treatment. 2022: Presented at: the Migraine Trust International Symposium (MTIS); 8–11 September 2022; London, UK. Poster number MTIS22-PO-031.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33(9):629–808.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Kiley Margolis, PharmD, of Lumanity Communications Inc. and Cassidy Bailey, PhD, of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio company, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and were funded by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.

Funding

This study and publication fees were funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dawn C. Buse, Lynda J. Krasenbaum, Michael J. Seminerio, Elizabeth R. Packnett, Karen Carr, Mario Ortega, and Maurice T. Driessen contributed to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual concepts. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dawn C. Buse has received research and/or consulting funding from Allergan/Abbvie, Amgen, Biohaven, Collegium, Lilly, Lundbeck, and Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. Maurice T. Driessen, Lynda J. Krasenbaum, and Mario Ortega are employees of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries. Elizabeth R. Packnett is an employee of Merative (IBM Watson Health at the time the study was conducted), which was contracted by Teva Pharmaceutical Industries to conduct this study. Michael J. Seminerio and Karen Carr were employees of Teva Pharmaceutical Industries at the time of the study but have since left the company; they are currently employees of AbbVie.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study, as only existing health care claims were used, and therefore, the data do not meet the definition of human subject research. As this study did not involve human participants or the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, institutional review board approval was not required. All data recorded on the databases were deidentified and fully compliant with US patient confidentiality requirements, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buse, D.C., Krasenbaum, L.J., Seminerio, M.J. et al. Real-world Impact of Fremanezumab on Migraine-Related Health Care Resource Utilization in Patients with Comorbidities, Acute Medication Overuse, and/or Unsatisfactory Prior Migraine Preventive Response. Pain Ther 13, 511–532 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-024-00583-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-024-00583-9