Abstract

Chronic nonmalignant pain is recognized as a complex, dynamic, phenomenological interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors that are individual to the person suffering from it. Therefore, its management and treatment ought to entail the individual’s biopsychosocial aspects that are often addressed by collaborative, inter/multidisciplinary multimodal care, as there is no biologic treatment. In an effort to enhance inter/multidisciplinary multimodal care, a narrative review of arts therapy as a mind–body intervention and its efficacy in chronic pain populations has been conducted. Changes in emotional and physical symptoms, especially pain intensity, during arts therapy sessions have also been discussed in in the context of attention distraction strategy. Arts therapy (visual art, music, dance/movement therapy, etc.) have been investigated to summarize relevant findings and to highlight further potential benefits, limitations, and future directions in this area. We reviewed 16 studies of different design, and the majority reported beneficial effects of art therapy in patients’ management of chronic pain and improvement in pain, mood, stress, and quality of life. However, the results are inconsistent and unclear. It was discovered that there is a limited amount of high-quality research available on the implications of arts therapy in chronic nonmalignant pain management. Due to the reported limitations, low effectiveness, and inconclusive findings of arts therapy in the studies conducted so far, further research with improved methodological standards is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Chronic nonmalignant pain is recognized as a complex, dynamic, phenomenological interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors. |

There has been a growing interest in exploring arts therapy for chronic nonmalignant pain management and this area of study remains rather unexplored. |

The authors try to analyze the relevant literature in order to suggest the implication of arts therapy in multimodal chronic pain management. |

Visual art therapy, music, dance/movement therapy, and written emotional disclosure therapy have been analyzed. |

The work brings interesting ideas on what and how to incorporate arts therapy into the treatment of chronic nonmalignant pain, but when searching and analyzing the included studies and their results, they encountered deep methodological problems and other limitations including a small sample of available clinical trials. |

Based on the review, it is not possible to clearly demonstrate the effect of arts therapy in the treatment of chronic nonmalignant pain and more research is needed. |

Introduction

People experiencing chronic pain usually present a multitude of overlapping issues including affective disorders such as anxiety, depression, heightened anger, fatigue and sleep disorders, reduced mobility and/or disability, loss of social role, social isolation, overuse of medication, and subsequent decrease in quality of life [1,2,3,4]. Over the last three decades, chronic nonmalignant pain has been recognized as a significant and costly issue, with evidence pointing to the lack of long-term efficacy of biomedical interventions such as opioid medication. Persistent use of opioids is correlated with declining benefit [5, 6] and a review of over 26,000 medical records has revealed that long-term use is correlated with increased psychological distress of pain patients over time [7].

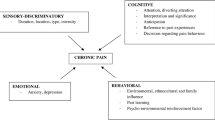

Given its complexity, chronic pain is now widely recognized as a phenomenological experience, whereby every individual’s pain perception is formed by one’s personal coping capacity, cultural notions of pain, quality of social relationships, and presence of other social stressors such as economic strain [3, 4, 8]. Therefore, the biopsychosocial model is now accepted as a comprehensive conceptualization for administering specialized pain management, as it draws upon the interactions of multiple factors associated with a person’s experience of pain [4, 9]. Needless to say, studies investigating implementation of the biopsychosocial model have largely been undertaken in interdisciplinary care settings (comprehensive programs with coordinated services provided in the same facility) [9]. Chronic pain mismanagement is contributed to by lack of education of health care providers [10]. The importance of remaining active when experiencing chronic pain is well known as that can lead to loss of strength and muscle tone [4]. Reduced fitness is associated with an increase in the experience of negative moods.

Arts Therapy as Psychotherapy and Mind–Body Intervention

An intervention that affects the mental and emotional state of an individual will also cause changes in the body. That is why these interventions are called "mind–body" [55].

Mind–body intervention is one aspect of a broad, holistic approach toward health and care, and it aims to promote overall health by focusing on interactions among brain, body, mind, emotion, and behavior [11]. Mind–body interventions have been widely used as a complementary and alternative intervention in special groups of participants with mental health issues [38, 44], chronically ill patients [37, 41, 61], and in cancer patients [36, 39, 52] showing positive effects in improvement of quality of life and symptom management and also for example in acute pain [11,12,13,14, 32, 36, 39, 52, 55]. Experiencing pain is not only on a somatic level [55], but also the brain, mind, body, emotions, and attention play important roles in the perception of pain. Pain is experienced through the centers of the brain that receive and process pain signals. They are brain centers where we know that attention, beliefs, emotions, distress, and cognitive tasks are processed.

We perceive arts therapy, or art-based therapy, in the use of creative therapies in the spectrum from art therapy, dance/movement therapy, writing therapy, bibliotherapy, drama therapy, music therapy, and others as described by authors Haen and Webb [53]. Arts therapy is one of the mind–body approaches, and it is based on engaging the senses and the body in therapy [15] and it provides a unique opportunity to benefit patients in improving their mental health [16, 56]. Arts therapy may help people cope with emotional suffering (to be less fearful, anxious or depressed), which enhances emotional awareness and acceptance and positively influences health [48]. Czamanski-Cohen and Weihs [48] synthesize the mind–body theory as it relates to art therapy. Art therapy can be beneficial in helping individuals with many problems. The body–mind model emphasizes and uses especially and above all the strengths of the individual. It also restores a sense of self, which is not necessarily related to any illness, chronic pain, cancer, or difficult life circumstances. Arts therapy is perceived as body–mind because the neuroscience describes the mechanisms of creation, description, and awareness of emotions in the brain. Emotions are evaluated in terms of meaning for individuals and context. Arts therapy is sensory experience and individual experience. For example, direct activity with materials activates the perception of structure, pressure, and temperature. Touch with the activation of muscle and joint movement makes it possible to understand, for example, the shape and weight of an object. Manipulation of objects or perception of motion is another phenomenon that activates emotional coloring before meaning is perceived [48].

Proposed Mechanisms Underlying Arts Therapy

When it comes to physical symptoms, it has been previously suggested that arts therapy serves as an attention distraction from pain [17,18,19], given that based on an observation of patients, pain perception of patients was greater when unoccupied [20]. Nevertheless, recent research suggests several explanations otherwise [21]. Heightened levels of attention to pain result in attentional prioritization of pain over other competing information that decreases distraction efficacy [22, 23]. The central sensitization hypothesis suggests that dysfunction occurs in central nociceptive pathways [24]. Compared to healthy participants, dysfunction in descending inhibitor pathways may explain the lesser efficacy in attention-distraction strategies for attenuating pain. Most notably, the connection between one’s ability to control pain and executive functioning (including attention) may be impaired in chronic pain patients. A meta-analysis of executive functioning (including attention) and pain control ability indicated that patients with chronic pain have reduced executive functioning abilities [25]. In that meta-analysis, heterogeneous experimental designs were used and data were pooled regardless of a specific diagnosis. The consistent evidence for small-to-moderate impairments was found in people with chronic pain within all cognitive components examined in the study—response inhibition, complex executive function, and set-shifting. However, studies could not separate processes.

In agreement with the findings described above [25], other authors recently found medium-to-strong evidence that executive functioning performance is reduced in patients with chronic pain compared to those without [26]. Three components of executive functioning were identified (inhibition, shifting, and updating), and all of them were similarly affected in chronic pain patients. In contrast, the correlation between chronic pain and executive functioning performance was not significant. Lower executive functioning could be a risk factor for greater vulnerability to chronic pain [26]. The effect of chronic pain status has also been found to affect the overall cognitive performance in fibromyalgia patients, mostly in divided-attention tasks where their performance was poorer than in a pain-free group [27].

It is evident that additional mechanisms to distract from pain, such as arts therapy, should be considered. These mechanisms can involve emotional processing and engagement with uncomfortable aspects of life. The experience of stress and strong negative emotions (anxiety, depression, or fear) are common in the process of chronic pain perception. Emotional processing refers to how emotions are experienced, exteroceptively and interoceptively (i.e., what happens inside the body, such as breathing, heartbeat, digestion, or pain) which can produce from pleasant to unpleasant feelings [54]. This is also related to how emotions are understood and expressed by individuals with chronic pain. We cognitively estimate the meaning of internal and external sensory information, always based on our life experience. The basic aspects of emotional processing are emotional awareness (the ability of the individual to describe and label affective experiences) and acceptance of emotions (the individual accepts their emotions). If somatic sensations are consciously processed either through speech or symbols, such as arts therapy, heightened emotional awareness will occur. It is further argued that beyond cognitive demands, motivational and emotional factors associated with the task for the individual may increase or reduce the distraction efficacy [28, 29]. Arguably, the varying inclination of the individual towards artistic expressions may influence the distraction efficacy. Needless to say, the empirical evidence for this idea thus far is confounding.

Neuroscience and Arts Therapy

The mechanisms behind the effect of arts therapy are not fully available. In cooperation with neuroscientists, further investigation of biological mechanisms to provide evidence of the effect of arts therapy is proving beneficial [57]. The need to understand the biological relationships for the effect of arts therapy is a response to methods that have attempted to measure the effect of arts therapy by describing the process of arts therapy. Brain imaging techniques, for example, nowadays help quantitatively measure subjective emotional states during arts therapy [57,58,59]. Arts therapy is related to neuroplasticity and sensomotor involvement, which is appropriate for investigating using neuroscience research protocols [59]. Research is currently being conducted in the field of arts therapy on neurobiological changes detected through salivary markers, heart rate, electroencephalography (EEG), functional magnetic resonance imaging, and functional near-infrared spectroscopy [57, 59]. The need to understand the biological relationships for the effect of arts therapy is a response to methods that have attempted to measure the effect of arts therapy by describing the process of arts therapy.

Although we need research in the field of neuroscience in relation to the effectiveness of arts therapy, emotions are proven to have a physiological basis, behavior and habits can be changed, and learning provides a cognitive basis for arts therapy. The process of arts therapy is related to emotional expression and finding different possible ways of behaving. The question is how to describe subjective and creative process. Therefore, it is difficult to verify and measure the effect of arts therapy and to generalize this effect in different types of populations (healthy patients, patients with chronic pain, etc.).

Objective and Aims of this Narrative Review

The use of arts therapy in the treatment of pain is not sufficiently researched in the context of evidence-based therapy and its cost-effectiveness.

While arts therapy is commonly used as a therapeutic approach in the treatment of pain, the publications work more or less with a case report or cross-sectional study design rather than a randomized controlled trial. The aim of this review is to examine and synthesize available literature using arts therapy in the treatment of nonmalignant pain patients to focus on available outcomes and effects of arts therapy in pain management and the potential costs of such treatment.

Methods

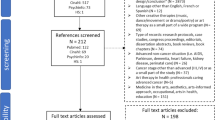

This review of relevant articles present in Google Scholar database, PubMed, and Cochran Database was completed on several occasions in June-November 2020 and was originally intended to be conducted according to the methods outlined in the PRISMA ScR guidelines extension for scoping reviews [30].

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The keywords applied were as follows: “chronic pain” and “arts therapy”. These were delimited to the last 20 years (from 2000 to November 2020) to English-language literature with studies on adult participants only. The article referred to nonmalignant chronic pain and randomized or cross-sectional design. Using these inclusion criteria, only three articles were found. Since we did not find enough studies to conduct scoping review, we decided to include other types of study design and to describe the results more narratively, as a narrative review only. This narrative review is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Therefore, all types of articles were included, i.e., reviews, clinical studies of different design, and case studies were set as the enhanced inclusion criteria for type of study design. We added other keyword terms such as “creative arts”, “pain management”, “visual art therapy”, “music therapy”, “dance therapy”, and “written therapy”. All articles were screened by title, abstract, and full text. We accepted full-text articles only in the English language. We focused on the utilization of arts therapy in treating nonmalignant pain among adults.

Results

Data Extraction and Synthesis

We identified 365 records through a database search. After removing duplicates and irrelevant topics, we found 51 articles concerning the topic and assessed the abstracts for eligibility. We excluded the abstract of 27 articles. Finally, we reviewed 24 eligible articles, which were in full-text format and different clinical design (review, clinical study, case study, and self-description). Eight more articles did not meet inclusion criteria and were excluded (cancer population n = 3; no chronic pain population n = 3; children population n = 1; acute pain population n = 1). At the end, we included 16 articles in the narrative review. The selection process of the referred articles is presented in Fig. 1. Table 1 shows characteristics and results of selected arts therapy studies in chronic pain management (visual art, music, written expression, and dance/movement therapy).

Data Analysis

We described the results only narratively because the studies found and included in the narrative review were not uniform in terms of study design, population, intervention, nor tools to measure pain and emotional state or other variables.

Thematically, we divided arts therapy into visual art therapy, music, dance/movement therapy, and written expression area.

Of the 16 studies found, eight dealt with visual art therapy [4, 20, 31, 33,34,35, 50, 51], one with music therapy [40], four with dance/movement therapy [42, 43, 49, 60], and three with written expression [45,46,47]. The representation of individual types of arts therapy was not uniform; the least in the field of music was one and the most in the field of visual art therapy were eight. Regarding the type of study design in the included 16 studies, there were five literature reviews [4, 20, 40, 49, 51], four nonrandomized clinical studies [31, 34, 42, 60], three self-reported evaluation and case studies [33, 35, 43], and four randomized designs [45,46,47, 50]. Overall, with regard to the type of design in the included studies, no type of study design (literature review, nonrandomized clinical study, self-reported evaluation and case study, randomization in design) predominated.

Six studies were supported by grants, specifically they were from the Foundation for Art and Healing [20], Johnson and Johnson and the Society for Arts in Healthcare [50], FEDER POCI-01–0145-FEDER-007746 [43], Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation; Arthritis Foundation; NIH grant R01 AR049059 [46], American Psychological Association; Stony Brook University; NIH Grant R01HD39753 [47] and Marian Chace Foundation, Columbia 170333-6754; Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine, Stratford, NJ; KIDaF Arts and Culture Foundation, Seoul, Korea [60]. Most of the included articles, ten, stated non funding [4, 31, 33,34,35, 40, 42, 45, 49, 51].

The majority of studies included in the narrative review, namely 12, were from the USA [20, 31, 33, 35, 40, 45,46,47, 49,50,51, 60]. Another smaller number, four studies, were conducted in Canada [4], Sweden [42], Israel [34], and Portugal [43]. Variables that were measured and targeted for analysis in 16 included studies of arts therapy were following: pain intensity [4, 20, 31, 34, 35, 40, 42, 43, 45,46,47, 50, 51, 60], emotional distress, mood, or wellbeing [4, 20, 31, 33, 34, 42, 43, 45,46,47, 49,50,51, 60], social support [20] and quality of life (QoL) [20, 35]. The included articles were published between 2004 and 2020 in this layout: 2004 [51], 2005 [45], 2006 [40, 46], 2008 [47], 2009 [33, 50], 2010 [20, 42], 2011 [4], 2012 [35], 2014 [34], 2017 [60], 2018 [31], 2019 [49], and 2020 [43].

Only one study [43] out of all 16 included in the review was registered, namely by registration in ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03493308 [43].

Of the total number of 16 included arts therapy studies, 12 were related to chronic nonmalignant diseases and chronic nonmalignant pain [4, 33, 35, 42, 43, 45,46,47, 49,50,51, 60], four studies mixed chronic diseases and chronic pain with cancer problems [20, 31, 34, 40], and in one study [40], a smaller part of the participants included in the analysis also had acute pain. All of the included studies worked with an adult population. Only in one study [40] was a smaller part of the participants included in the analysis children, with the majority being adults. Most of the studies worked with unevenly classified gender of the participants; five studies [33,34,35, 42, 45] included only females.

Visual Art

In the field of visual art therapy, eight included studies, we can find these types of designs included in the studies: three literature reviews [4, 20, 51], two nonrandomized clinical studies [31, 34], two self-reported evaluation and case studies [33, 35], and one randomized study [50].

For those eight studies included in the article in the field of visual art therapy, three studies of literature review design predominated [4, 20, 51] and two studies of nonrandomized clinical design [33, 35] at the expense of one study with randomized design [50] and two of case study design [33, 35].

The results of inhomogeneous design of the studies included in this part of visual art therapy were mainly concerned with improvement of pain intensity [4, 20, 31, 33,34,35, 50, 51], emotional distress, mood or wellbeing [4, 20, 31, 33, 34, 50, 51], social support [20], and quality of life (QoL) [20, 35].

It is necessary to note that the results were measured by different methods and instruments in each study of different design.

There has been growing evidence that visual art therapy sessions containing art-making (i.e., making of art) raise the efficiency of art therapy and contribute to better pain management [31, 33, 50]. One of the qualitative studies, where a protocol combined art and cognitive-behavioral interventions (CB-ART) was used to help women manage pain, anxiety, and depressive symptoms [34], and one [50], anxiety, connected to pain. Passive art therapy [4] (when participants do not make art actively) can also especially improve emotional suffering connected with pain. Results, although coming from studies of different design, showed a reduction of distress in all participants, and they also acknowledge the possibility of using participants’ art products for further examination of maladaptive cognitions and behaviors. As opposed to the art therapy intervention design in the studies above, another study used an entirely spontaneous and self-directed design in art-making [35]. They identified two additional themes associated with the therapeutic use of art-making: quality of life and giving back to others. Unfortunately, studies in this research area focused on different designs from literature reviews to clinical studies, on limited range of participants, mainly individual diagnostic groups composed of women [4, 31, 34, 35], and limited variance of study designs, typically pre-intervention and post-intervention comparison within the treated groups [20, 33, 35, 50].

Music

One of the studies related to music therapy is a review of randomized controlled trials [40]. It is the only study of this kind included in our review.

In the field of music therapy, we included only one study with a literature review of randomized controlled trials design.

The results of one study included in this part of therapy were mainly concerned with improvement of pain intensity and on reducing of opioid requirements [40]. Although it is clear from the literature that one of the most accessible and most researched media of art and healing is music [4, 20, 51], we did not find more than one study [40] that would fulfill the inclusive criteria, especially nonmalignant adult pain population. Therefore, we decided to discuss it with similar studies, which were not investigated primarily on the population with chronic nonmalignant pain. Effect of music was studied in one systematic review [37], where studies ranged from older adult participants, war veterans, and prison inmates. Employment of music therapy as an intervention helped and improved mood, socialization, and problem-solving abilities [38]. A significant effect of music therapy was found in all categories except in people with schizophrenia [37, 38]; however, more randomized controlled trials are necessary to verify the effect. Moreover, art therapy sessions, including music therapy, indicate improvement in mood, enhanced social and emotional wellbeing, improved quality of life, and reduced fatigue in that studies [37, 38]. In contrast, publications on the effectiveness of art therapy and music for pain patients do not show significant results in pain reduction [40]. The authors concluded that listening to music can reduce pain intensity levels and opioid requirements in a mixed pain population, but positive effects were rather small [40]. Since only one study was found, we cannot draw any conclusions for chronic pain management.

Dance and Movement Therapy

In the field of dance and movement therapy (four included studies), it may be found: one literature review [49], two nonrandomized clinical studies [42, 60], and one case study [43]. For those four studies included in the article in the field of dance and movement therapy, two studies with nonrandomized clinical study design at the expense of studies with case study design and literature review design. The results of inhomogeneous design of the studies included in this part of art therapy were mainly concerned with improvement of pain intensity [42, 43, 60] and emotional distress, mood, or wellbeing [42, 43, 49, 60]. The results were measured by different methods and instruments in each study of different design. The growing interest in this area of research is a result of recent evidence indicating that several health benefits can be achieved through the creative movement of mind and body. For instance, stress and anxiety can be relieved, and one’s quality of life can improve [20, 41, 43, 49]. In one included study, participants cooperated with professional actors and dance movement therapists [42]. Each participant recorded three different video films, and afterwards, self-rate scales of the intensity of emotional expressions were completed. Measuring was repeated at 3 and 6-month follow-ups. Increase in self-rated health and decrease in pain was observed. Moreover, there was a correlation between strong emotional expression and a decrease in pain when engaging in dance and movement therapy. The effect of dance and movement therapy on various biopsychosocial issues associated with chronic pain and resilience was also confirmed in the chronic pain population [43, 60]. Because cardiovascular activity and movement are welcome in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain (who typically avoid exercise), this form of arts therapy appears to be another possible offering to enhance activity. Studies in this research area of arts therapy focused on different designs from literature reviews to clinical studies and to case studies on a limited range of participants, mainly individual diagnostic groups composed of women [42] and limited variance of study designs [42, 43, 60].

Written Expression

In the field of written expression (three included studies), we can find these types of design included in the studies: randomized studies [45,46,47]. All included studies in the field of written expression were designated as randomized design. Variables that were measured and targeted for analysis in that art therapy were the following: pain intensity [45,46,47], emotional distress, mood or wellbeing [45,46,47]. The results were measured by different methods and instruments in each study. Expressive writing has been used with a broad range of patients in one-to-one interventions and formal and informal groups [44]. This encourages people with mental or physical problems to enjoy and express themselves and develop creativity and empowerment. The written expression of traumatic experiences is also an effective intervention; for example in fibromyalgia patients who suffer from pain. The study, where patients were randomized into two writing groups, aimed to observe three main variables: psychological wellbeing, pain, and fatigue. In the context of short-term results, the written expression had a significant effect in reducing pain and fatigue, however, benefits did not last until the 10-month follow-up [45]. The efficacy of written emotional disclosure about stressful experiences was also studied when conducted at home [46]. Despite the significant results of the previously mentioned study [45], immediate increase in negative mood and a nonsignificant reduction in pain was observed with writing disclosure at home [46]. Patients with chronic pain further profit from written anger expression, since it helps them to improve perceived control over pain and depressed mood and to achieve more significant improvement in pain severity [47]. Because in patients with chronic nonmalignant pain we often encounter traumas, which they bring to therapy, this form of arts therapy is shown to be one of the possibilities for managing traumas with patients. Although the three included studies had a randomized design, each measured variables with different methods and instruments and also had a different program of arts therapy. Also, the setting of individual or group forms of therapy was different in each study. Although the health problems of all three studies were similar (fibromyalgia and chronic pain), the results from these three studies are also difficult to generalize, but the group with this type of arts therapy and included studies seems the most suitable for data analysis, however the number of studies (three) is very small. Studies in this research area of arts therapy focused on the limited range of participants; one composed study was only on women [45].

Discussion

In all four areas of arts therapy addressed in this narrative review (visual art, music, dance/movement therapy, and written expression) there is reasonable evidence that artistic involvement (i.e., arts therapy) is associated with a positive effect on health [31, 35, 37, 42, 43, 47, 49]. Frequently identified benefits were: improvement in mood, distress or wellbeing [4, 20, 31, 33, 34, 42, 43, 45,46,47, 49,50,51, 60], overall quality of life [20, 35], and decrease in pain intensity [4, 20, 31, 34, 35, 40, 42, 43, 45,46,47, 50, 51, 60]. However, there are design limitations to many of the studies included in this review and randomized controlled trials are needed to assess efficacy. The sample of studies included in this review was often limited to reviews [4, 20, 40, 49, 51], case studies [33, 35, 43], or individual and specific diagnostic groups of chronic illnesses related to pain (low back pain, fibromyalgia, HIV, etc.) or included in a mixed-sample cancer population [20, 31, 34]; therefore, a generalization of results cannot be made yet. Furthermore, many of the studies were confined only to pre-intervention and post-intervention comparison within the treated group [20, 31, 34, 42, 49, 60]. There are only four included randomized studies in our review: one [50] deals with the effect of visual art and the other three [45,46,47] with the effect of written expression on pain and emotion. The number of cases is insufficient, and they are not equally distributed across all four areas of art therapy, making it challenging to draw consistent conclusions.

In regards to the results of most studies in this review, the biopsychosocial model, which has been widely accepted among art therapists, appears to be a workable conceptualization of chronic pain, since multiple factors are included. The literature appeared to emphasize treating the psychological aspects of chronic pain; however, some findings suggest that arts therapy could also reduce the physical symptoms in some patients [31] or decrease the pain intensity [4, 20, 31, 34, 35, 40, 42, 43, 45,46,47, 50, 51, 60]. Changes in pain symptoms during arts therapy intervention were discussed in the context of providing an efficient attention distraction from pain and related emotion [31, 33,34,35, 42, 43, 45,46,47, 50, 60]. It is evident that additional mechanisms to distract from pain might include emotional processing and other approaches.

The results from the included studies are described narratively; we did not synthesize or critically evaluate the results due to their inconsistency, which made it impractical. That is why most studies did not focus on the cost-effectiveness of therapy, as there is no way to evaluate it. Only one study [40] which looked at the effectiveness of music in arts therapy on pain intensity, not on emotion, attempted to address this in line with the pharmacological reduction of opioid therapy use. A further study investigated on the effects of dance therapy [42]. In conclusion, it states that inclusion of expression therapy could reduce health care costs in individuals with pain. It does describe how this could be obtained, and does not provide evidence of the cost-efficacy of the method.

Although there are limitations in arts therapy, the importance of this kind of management in patients affected by chronic pain has been described in many studies [31, 33,34,35, 42, 43, 45,46,47, 50, 60]. Improvement in chronic pain management was also observed in art-making sessions. However, in this review the findings were inconsistent within the design of cited studies [4, 20, 31, 33,34,35, 50, 51]. Especially in music therapy, arts therapy used in chronic nonmalignant pain population has provided good results on emotions and QoL of the patients [40]. It is known that listening to music or performing music can be controlled and have a strong capacity to capture attention, shifting it away from the unpleasant sensation of pain. This is why it is interesting to check the effect of this arts therapy in future studies. The written emotional disclosure benefited people in managing the pain and perceiving control over it in included studies in our review [45,46,47, 50]. We found only a limited number of studies on dance and movement therapy due to methodological shortcomings and heterogeneity of outcome measures in research within this area [42, 43, 60].

Limitations and Positives

In addition to the small number of studies of arts therapy in chronic nonmalignant pain population found (only 16), methodological problems must be mentioned first. The representation of individual types of arts therapy was not uniform, with only one study found in the field of music therapy. A limitation of this narrative review is that we pooled inhomogeneous study design studies and thus reported the results only narratively without bias. The review does not synthesize and critically evaluate the results of the studies, which is not even possible due to their inconsistency. A second limitation is the focus on English-language studies only, and restriction of the authors’ search strategy to only three databases (Google Scholar, PubMed, and Cochran Database). Another limitation is that we were not able to assess risk or prevention of pain experience and related problems and how arts therapy affects the experience of pain over time. This would require longitudinal studies; and to verify the effect, it would be more appropriate to use only randomized study designs. Another limit of the review of arts therapy can be in mixing a chronic nonmalignant pain population with various clinical diseases that accompany pain and the mixing of cancer and nonmalignant pain participants. The experience can be different, and there may be different emotional and behavioral problems associated with pain in these two types of pain (cancer and nonmalignant pain). Mixed clinical diseases included in reviewed articles can influence the specific manifestations of individual diseases associated with pain. Although this applies to only a few included studies, and it was noticeable only after deep review [20, 31, 34, 40], this limitation should be mentioned. Further, the studies involved in this review were composed partly or completely [33,34,35, 42, 45] of women participants only. Generally, included clinical studies contained only a small sample of participants. In the included studies, we also did not find information on whether arts therapy approaches were less expensive than traditional approaches involved in multidisciplinary chronic pain management. This will need to be done in a systematic review and meta-analysis. We would also like to mention the limitations regarding the arts therapist. The certified art therapist in the treatment of pain is a specially trained mental health worker, usually a psychotherapist, with several years of training and supervision. These costs should also be taken into account in further studies and the possible reason why there are not many such studies. It is also necessary to focus on the fact of who performed arts therapy in the studies; for example, the only study [42] clearly stated that it was an arts therapist, not described in the other studies. Who has performed the therapy should represent an important aspect. In the examined studies, just one provided a clear indication on the fact that therapy had been performed by a certified arts therapist [42]. In fact, there are clear differences between recreational or professional art therapists, also for ethical reasons. The professional art therapists have a solid psychotherapeutic background, not present in people interested in recreational art therapy. Art therapy has shown promise in treating chronic pain and related emotion in some individuals and chronic diseases related to chronic pain, but the effects were not consistent across studies. In a recent study, it also resulted useful in the management of acute pain [62]. For arts therapy studies to be meaningful, researchers must specify precisely what kind of arts therapy was being conducted and not to use multiple types of arts therapy. The use of the term "arts therapy" was also in included studies too flexible, as it often included different modalities of arts therapy.

It can be summed up as a positive, we perceive arts therapy as an integral part of the body–mind approach in chronic pain treatment and tried in that narrative review to summarize what is known about arts therapy in the literature, analyze it, and prove its effectiveness on the complex experience of chronic pain. Arts therapy has potential, but its effectiveness and cost-effectiveness compared to other more expensive approaches in treatment of chronic pain need to be proven. However, it provides clinicians with a holistic view of chronic nonmalignant pain therapy that can be individualized as a non-pharmacological method that has minimal side effects.

Conclusions

At the moment, there is too little high-quality research on the implications of arts therapy in chronic nonmalignant pain management; however, it seems a promising area of study. Finding effective mechanisms and their effectiveness could inspire further research into possible mechanisms at work in arts therapy and its types and in chronic nonmalignant pain management. There are several issues that should be considered in future studies to acquire methodological standards. Researchers should seek to establish meaningful control groups and to quantify outcome variables at higher levels. In addition, more precise findings regarding treatment characteristics could provide new hypotheses for especially future randomized studies. For example, the effectiveness of certain types of arts therapy for specific treatment indications. Furthermore, there is a challenge in finding evidence for the long-term effects of arts therapy. Although there has been a growing interest in exploring arts therapy for chronic pain management, this area of study remains rather unexplored and more research is needed. It remains an important topic for future research.

Currently, it appears that most studies investigating arts therapy in chronic nonmalignant pain management are focused on exploring a new approach to deliver more holistic treatment. So far, the results of this narrative review do not allow drawing any general conclusions.

However, if we also had the results from randomized studies and meta-analyses, we could recommend arts therapy as part of a holistic approach to the treatment of chronic non-malignant pain. Yet, current hybrid forms and multi-media of art-making such as performance art, body art, and collaborative open forms may promise even more intensive effects and use in the medical field of art therapy in the future. In this area, a creative grasp of established practices is definitely offered and innovative practice can also be expected in mixed teams of psychotherapists, artists, and pain specialists.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Camilloni A, Nati G, Maggiolini P, et al. Chronic non-cancer pain in primary care: an Italian cross-sectional study. Signa Vitae. 2021;17(2):54–62. https://doi.org/10.22514/sv.2020.16.0111.

Latina R, De Marinis MG, Giordano F, et al. Epidemiology of chronic pain in the Latium Region, Italy: a cross-sectional study on the clinical characteristics of patients attending pain clinics. Pain Man Nurs. 2019;20(4):373–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2019.01.005.

Paterniani A, Sperati F, Esposito G, et al. Quality of life and disability of chronic non-cancer pain in adult patients attending pain clinics: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. App Nurs Res. 2020;56: 151332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151332.

Angheluta AM, Lee BK. Art therapy for chronic pain: applications and future directions. Can J Couns Psychother [Internet]. 2011;45(2):112–131. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ930794.pdf Accessed Oct 5.

Chou R. Steering patients to relief from chronic low back pain: opioids' role. J Fam Pract [Internet]. 2013;62(3 Suppl):S8-S13. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84879526044&partnerID=40&md5=cdd9b83790fc98b8dfe066aa5bd5e397. Accessed Oct 15.

Krashin D, Sullivan M, Ballantyne J. What are we treating with chronic opioid therapy? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15(3):311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-012-0311-1.

Von Korff M, Kolodny A, Deyo RA, Chou R. Long-term opioid therapy reconsidered. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(5):325–8. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-155-5-201109060-00011.

Collen M. Life of pain, life of pleasure: pain from the patients’ perspective—the evolution of the PAIN exhibit. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2005;19(4):45–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/J354v19n04_08.

Liampas A, Hadjigeorgiou L, Nteveros A, et al. Adjuvant physical exercise for the management of painful polyneuropathy. Postgrad Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2021.2004733.

Phillips C. The real cost of pain management: editorial. Anaesthesia. 2008;56(11):1031–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2001.02367.x.

Elkins G, Fisher W, Johnson A. Mind–body therapies in integrative oncology. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2010;11(3–4):128–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-010-0129-x.

Morone NE, Greco CM. Mind–body interventions for chronic pain in older adults: a structured review. Pain Med. 2007;8(4):359–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00312.x.

Antonucci LA, Taurino A, Laera D, et al. An ensemble of psychological and physical health indices discriminates between individuals with chronic pain and healthy controls with high reliability: a machine learning study. Pain Ther. 2020;9(2):601–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00191-3.

Mayden KD. Mind–body therapies: evidence and implications in advanced oncology practice. J Adv Pract Oncol [Internet]. 2012;3(6):357–373. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4093363/. Acessed Oct 18, 2020.

Monti DA, Sufian M, Peterson C. Potential role of mind–body therapies in cancer survivorship. Cancer. 2008;112(S11):2607–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23443.

Geue K, Goetze H, Buttstaedt M, Kleinert E, Richter D, Singer S. An overview of art therapy interventions for cancer patients and the results of research. Complement Ther Med. 2010;18(3–4):160–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2010.04.001.

Dannecker K. Body and expression: art therapy with rheumatoid patients. Am J Art Ther. 1991;29(4):110–117. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.is.cuni.cz/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=asn&AN=961031351 9&lang=cs&site=eds-live&scope=site. Accessed Oct 25, 2021

Reynolds F, Prior S. ‘A lifestyle coat-hanger’: a phenomenological study of the meanings of artwork for women coping with chronic illness and disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(14):785–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963828031000093486.

Shapiro B. “All I have is the pain”: Art therapy in an inpatient chronic pain relief unit. Am J Art Therapy. 1985;24(2):44–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2015.1091642.

Stuckey HL, Nobel J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: a review of current literature. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):254–63. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497.

Verhoeven K, Van Damme S, Eccleston C, Van Ryckeghem D, Legrain V, Crombez G. Distraction from pain and executive functioning: an experimental investigation of the role of inhibition, task switching and working memory. Eur J Pain. 2011;15(8):866–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.01.009.

Crombez G, Viane I, Eccleston C, Devulder J, Goubert L. Attention to pain and fear of pain in patients with chronic pain. J Behav Med. 2013;36(4):371–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-012-9433-1.

Vlaeyen JWS, Morley S, Crombez G. The experimental analysis of the interruptive, interfering, and identity-distorting effects of chronic pain. Behav Res Ther. 2016;86:23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.08.016.

Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain. 2011;152(3):S2-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.030.

Berryman C, Stanton TR, Bowering KJ, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Moseley GL. Do people with chronic pain have impaired executive function? A meta-analytical review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(7):563–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.08.003.

Bunk S, Preis L, Zuidema S, Lautenbacher S, Kunz M. Executive functions and pain. Z Neuropsychol. 2019;30(3):169–96. https://doi.org/10.1024/1016-264X/a000264.

Moore DJ, Meints SM, Lazaridou A, Johnson D, Franceschelli O, Cornelius M, et al. The effect of induced and chronic pain on attention. J Pain. 2019;20(11):1353–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.05.004.

Schrooten MG, Van Damme S, Crombez G, Peters ML, Vogt J, Vlaeyen JW. Nonpain goal pursuit inhibits attentional bias to pain. Pain. 2012;153(6):1180–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2012.01.025.

Eccleston C, Crombez G. Advancing psychological therapies for chronic pain. F1000Res. 2017;6:461. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.10612.1.

Tricc AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters M, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Shella TA. Art therapy improves mood, and reduces pain and anxiety when offered at bedside during acute hospital treatment. Arts Psychother. 2018;57:59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.10.003.

Stinley NE, Norris DO, Hinds PS. Creating mandalas for the management of acute pain symptoms in pediatric patients. Art Ther. 2015;32(2):46–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2015.1028871.

Hass-Cohen N, Findlay JC. Pain, attachment, and meaning making: report on an art therapy relational neuroscience assessment protocol. Arts Psychother. 2009;36(4):175–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2009.02.003.

Czamanski-Cohen J, Sarid O, Huss E, Ifergane A, Niego L, Cwikel J. CB-ART—the use of a hybrid cognitive behavioral and art based protocol for treating pain and symptoms accompanying coping with chronic illness. Arts Psychother. 2014;41(4):320–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.05.002.

Kelly CG, Cudney S, Weinert C. Use of creative arts as a complementary therapy by rural women coping with chronic illness. J Holist Nurs. 2012;30(1):48–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010111423418.

Nainis N, Paice JA, Ratner J, Wirth JH, Lai J, Shott S. Relieving symptoms in cancer: innovative use of art therapy. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2006;31(2):162–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.006.

Maujean A, Pepping CA, Kendall E. A systematic review of randomized controlled studies of art therapy. Art Ther. 2014;31(1):37–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2014.873696.

Gussak D. The effects of art therapy on male and female inmates: advancing the research base. Arts Psychother. 2009;36(1):5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2008.10.002.

Ennis GM, Kirshbaum M, Waheed N. The energy-enhancing potential of participatory performance-based arts activities in the care of people with a diagnosis of cancer: an integrative review. Arts Health. 2019;11(2):87–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2018.1443951.

Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Lau J, Alvarez H. Music for pain relief. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD004843. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004843.pub2.

Kiepe MS, Stöckigt B, Keil T. Effects of dance therapy and ballroom dances on physical and mental illnesses: a systematic review. Arts Psychother. 2012;39(5):404–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.06.001.

Horwitz EB, Kowalski J, Anderberg UM. Theater for, by and with fibromyalgia patients – evaluation of emotional expression using video interpretation. Arts Psychother. 2010;37(1):13–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2009.11.003.

Simões P, Andias R, Simões D, Silva AG. Group pain neuroscience education and dance in institutionalized older adults with chronic pain: a case series study. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;15:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2020.1728794.

Mcardle S, Byrt R. Fiction, poetry and mental health: expressive and therapeutic uses of literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2001;8(6):517–24. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1351-0126.2001.00428.x.

Broderick JE, Junghaenel DU, Schwartz JE. Written emotional expression produces health benefits in fibromyalgia patients. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(2):326–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000156933.04566.bd.

Gillis ME, Lumley MA, Mosley-Williams A, Leisen JC, Roehrs T. The health effects of at-home written emotional disclosure in fibromyalgia: a randomized trial. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32(2):135–46. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3202_11.

Graham JE, Lobel M, Glass P, Lokshina I. Effects of written anger expression in chronic pain patients: making meaning from pain. J Behav Med. 2008;31(3):201–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-008-9149-4.

Czamanski-Cohen J, Weihs KL. The bodymind model: a platform for studying the mechanisms of change induced by art therapy. Arts Psychother. 2016;51:63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2016.08.006.

Shim M, Goodill S, Bradt J. Mechanisms of dance/movement therapy for building resilience in people experiencing chronic pain. Am J Dance Ther. 2019;41(1):87–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-019-09294-7.

Rao D, Nainis N, Williams L, Langner D, Eisin A, Paice J. Art therapy for relief of symptoms associated with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):64–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120802068795.

Pratt RR. Art, dance, and music therapy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2004;15(4):82–41, vi–vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2004.03.004.

Puig A, Min Lee S, Goodwin L, Sherrard PAD. The efficacy of creative arts therapies to enhance emotional expression, spirituality, and psychological well-being of newly diagnosed Stage I and Stage II breast cancer patients: A preliminary study. Arts Psychother. 2006;33(3):218–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2006.02.004.

Haen C, Webb NB, editor. Creative arts-based group therapy with adolescents theory and practice. New York: Routledge; 2018. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203702000.

Czamanski-Cohen J, Wiley JF, Sela N, Caspi O, Weihs K. The role of emotional processing in art therapy (REPAT) for breast cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(5):586–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2019.1590491.

Hassed C. Mind–body therapies–use in chronic pain management. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(3):112–7 (PMID: 23529519).

Angheluta AM, Lee BK. Art Therapy for Chronic Pain: Applications and Future Directions. Can J Couns Psychother. 2011;45(2). https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/article/view/59289.

King JL, Kaimal G, Konopka L, Belkofer C, Strang CE. Practical applications of neuroscience-informed art therapy. ArtTherapy. 2019;36(3):149–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2019.1649549.

Walker MS, Stamper AM, Nathan DE, Riedy G. Art therapy and underlying fMRI brain patterns In military TBI: a case series. Int J Art Ther. 2018;23(4):180–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2018.1473453.

King JL, Kaimal G. Approaches to research in art therapy using imaging technologies. Front Hum Neurosci. 2019;13:159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00159.

Shim M, Johnson RB, Gasson S, Goodill S, Jermyn R, Bradt J. A model of dance/movement therapy for resilience-building in people living with chronic pain. Eur J Integr Med. 2017;9:27–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2017.01.011.

Koch SC, Riege RFF, Tisborn K, Biondo J, Martin L, Beelmann A. Effects of dance movement therapy and dance on health-related psychological outcomes. a meta-analysis update. Front Psychol. 2019;10:186. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01806.

Giordano F, Giglio M, Sorrentino I, Dell'Olio F, Lorusso P, Massaro M, Tempesta A, Limongelli L, Selicato L, Favia G, Varrassi G, Puntillo F. Effect of preoperative music therapy versus intravenous midazolam on anxiety, sedation and stress in stomatology surgery: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Med. 2023;12(9):3215. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093215.

Acknowledgements

The opinions expressed in article by the authors are those of the authors only.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Funding

This study is partially supported by the grant HORIZON 2020, No. 870621/AMASS—Acting on the Margin—Arts as a Social Sculpture. The authors are also grateful to the Paolo Procacci Foundation for its support on the editorial activities for the publication. No funding was received for publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jaroslava Raudenska processed the main concept and design of article. Jaroslava Raudenska, Alena Javurkova, and Veronika Steinerova carried out most of the selection of the articles. Jaroslava Raudenska, Alena Javurkova, and Sarka Vodickova drafted the initial manuscript. All the authors contributed to the review and provided critical revisions to enhance the quality of the paper. All of the authors reviewed and approved the final draft of the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Jaroslava Raudenska, Veronika Šteinerova, Šárka Vodičková, Martin Raudensky, Marie Fulkova, Ivan Urits, Omar Viswanath, Magdi Hanna, Giustino Varrassi, and Alena Javurkova have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Raudenská, J., Šteinerová, V., Vodičková, Š. et al. Arts Therapy and Its Implications in Chronic Pain Management: A Narrative Review. Pain Ther 12, 1309–1337 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00542-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00542-w