Abstract

Introduction

Treatment target goals for patients receiving preventive migraine treatment are complicated to assess and not achieved by most patients. A headache “number” could establish an understandable treatment target goal for patients with chronic migraine (CM). This study investigates the clinical impact of reduced headache frequency to ≤ 4 monthly headache days (MHDs) as a treatment-related migraine prevention target goal.

Methods

All treatment arms were pooled for analysis from the PROMISE-2 trial evaluating eptinezumab for the preventive treatment of CM. Patients (N = 1072) received eptinezumab 100 mg, 300 mg, or placebo. Data for the 6-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC), and acute medication use days were combined for all post-baseline assessments and analyzed by MHD frequency (≤ 4, 5–9, 10–15, > 15) in the 4 weeks preceding assessment.

Results

Based on pooled data, the percentage of patient-months with ≤ 4 MHDs associated with “very much improved” PGIC was 40.9% (515/1258) versus 22.9% (324/1415), 10.4% (158/1517), and 3.2% (62/1936) of patient-months with 5–9, 10–15, and > 15 MHDs, respectively. Rates of patient-months with ≥ 10 days of acute medication use were 1.9% (21/1111, ≤ 4 MHDs), 4.9% (63/1267, 5–9 MHDs), 49.5% (670/1351, 10–15 MHDs), and 74.1% (1232/1662, > 15 MHDs). Of patient-months with ≤ 4 MHDs, 37.1% (308/830) were associated with “little to none” HIT-6 impairment versus 19.9% (187/940), 10.1% (101/999), and 3.7% (49/1311) of patient-months with 5–9, 10–15, and > 15 MHDs, respectively.

Conclusion

Participants improving to ≤ 4 MHDs reported less acute medication use and improved patient-reported outcomes, suggesting that 4 MHDs may be a useful patient-centric treatment target when treating CM.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02974153) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02974153).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Data from this post hoc analysis of PROMISE-2 support the use of 4 or fewer monthly headache days as a targeted treatment goal for patients with chronic migraine. |

Patients who had ≤ 4 monthly headache days had a higher percentage of patient-months reporting “very much improved” and “much improved” on patient-reported outcomes. |

Treatment goals should be 4 or fewer headache days per month rather than 50% reduction in monthly migraine frequency, which for patients with high migraine frequency, may still be substantial. |

Having clearly articulated treatment goals will help improve communication between patients and health care providers and clarify meaningful treatment outcomes. |

Introduction

Headache disorders such as episodic (EM) and chronic migraine (CM) are major contributors to long-term disability and the global burden of disease [1, 2]. According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3), CM is defined as ≥ 15 headache days per month for at least 3 months, of which at least 8 headache days per month are phenotypically migraine [3]. CM, in particular, is associated with substantial migraine-related disability, including reduced productivity at work or school and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [4,5,6]. While the diagnosis and frequency of migraine attacks is often expected to be relatively stable for an individual patient, evidence suggests that headache frequency is quite variable over time, with some individuals oscillating between EM and CM [7].

The term “migraine chronification” is used when EM evolves into a CM disorder [8]. The likelihood of chronification may be influenced by inadequately managed migraine with sustained high frequency of migraine/headache attacks, familial factors, comorbidities, lifestyle, and poor optimization or excessive use of acute treatment [9]. Chronification and inadequately controlled migraine not only impacts headache severity, they also contribute to other migraine-related comorbidities, including depression, medication overuse, gastrointestinal complaints, sleep disorders, and muscle pain [8, 9]. Previous research has indicated a clear correlation between baseline headache frequency and the risk of transitioning from EM to CM, with risks lowest for those averaging ≤ 4 migraine headache days per month [9]. Those with CM report higher internal and enacted stigma than those with EM [10]. Additionally, many studies have demonstrated that patients with higher headache frequency report lower HRQoL and greater levels of disability on the Migraine Disability Assessment questionnaire and the 6-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) [6, 11].

The 2021 consensus statement from the American Headache Society (AHS) outlines specific criteria for the initiation of preventive migraine treatment, with the comprehensive treatment target of reducing overall disease burden. These guidelines for initiating preventive treatment include migraine attacks that significantly disrupt a patient’s daily routines despite acute treatment; frequent attacks (≥ 3 headache days/month with severe disability; ≥ 4 headache days/month with some disability; ≥ 6 headache days/month with any level of disability); contraindication to, failure, or overuse of acute treatments; adverse events with acute treatments; and patient preference [12].

According to the United States Food and Drug Administration 2018 guidance for clinical trials, the primary outcome measure of acute migraine treatment should be freedom from pain and a reduction or resolution of the most bothersome symptom (i.e., nausea, phonophobia, or photophobia) at 2 h post dosing of a migraine headache of moderate to severe intensity [13]. In contrast, the treatment endpoints for patients in clinical trials of preventive migraine treatment have been more difficult to assess and implement, with current regulatory guidelines recommending a ≥ 50% or ≥ 75% reduction in monthly migraine days (MMDs) within 3 months for treatments delivered monthly or 6 months for treatments delivered quarterly [14,15,16]. Unfortunately, many patients with a history of frequent migraine do not achieve this target [16], and the target is often confusing for both patients and treating clinicians working to implement these clinical trial treatment targets into clinical practice.

In addition to having treatment targets that are difficult to communicate and assess, the attack frequency of migraine often varies over time within and between patients [7], making clinical decisions difficult without an accurate pre-treatment baseline or a placebo control. This challenge is further amplified when there is no clearly defined therapeutic clinical target established for acute preventive migraine therapeutics. Clinicians informing patients to expect the same degree of change in monthly headache days (MHDs) post treatment as exhibited in placebo-controlled clinical trials may lead to unrealistic treatment targets or expectations for each patient. It is common for patients with migraine to discontinue traditional preventive therapies because of an insufficient response and/or poor tolerability [17, 18], which may further complicate the treatment timeline and interpretation of success.

Furthermore, a patient’s reduction in MHDs is typically quantified through diary documentation often complicated by diary fatigue, poor compliance, and inaccurate recall [19]. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), such as HIT-6 and Migraine Disability Assessment, which assess the impact of disease on patient functioning and disability, are not consistently used in the clinical setting [12], and there is a lack of clarity regarding measurement aim and methodological quality (i.e., reliability and validity that impact data interpretation) [20, 21]. In addition, there is no consensus regarding which PRO measure best captures treatment efficacy from the patient’s perspective [20]. Similar to treatment target numbers that have been established in other therapeutic areas (e.g., diabetes HbA1c level, systolic/diastolic blood pressure treatment targets for hypertension, and serum cholesterol/lipoprotein levels for the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease) that promote shared treatment targets and a collaboration between health care providers and patients [22,23,24], a headache “number” could establish an easily understandable treatment target of prevention outcome for patients with CM and other high-risk migraine populations (e.g., high-frequency EM, CM with medication overuse headache [MOH]). While it may be argued that numbers used in other disease states have measurable metrics, they are often silent diseases with minimal symptomatology. Migraine, on the other hand, has, as its metric, severe and obvious symptomology; however, it is often unwitnessed by health care providers and requires clinicians to rely on patient histories.

Eptinezumab is a humanized immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) monoclonal antibody that inhibits calcitonin gene-related peptide and is approved for the preventive treatment of migraine in adult participants with episodic and chronic disease [25,26,27]. The two pivotal phase 3 trials, PROMISE-1 in participants with EM and PROMISE-2 in participants with CM, determined that intravenous (IV) injection of eptinezumab (100 mg or 300 mg) achieved the primary efficacy endpoint by significantly decreasing mean MMDs over weeks 1–12 [28, 29]. Given that previous research has indicated that those patients averaging ≤ 4 headache days per month have lower risk of chronification and lower need for preventive treatment, this post hoc analysis used pooled data from the PROMISE-2 clinical trial to investigate the clinical impact of reducing a patient’s headache frequency to ≤ 4 headache days per month as a treatment-related migraine prevention target for health care providers. Pooled treatment and placebo data were utilized because the focus here is on achieving a treatment target of no more than 4 headache days per month and not on the benefits of eptinezumab treatment specifically. This goal of no more than 4 headache days per month would then potentially serve as the point for sustained positive response and a minimal risk for chronification or acute medication overuse.

Methods

Data Source

The detailed methodology for PROMISE-2 has been published previously [29]. In brief, PROMISE-2 was a phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study conducted at 128 study sites in 13 countries from 30 November 2016 to 20 April 2018, that evaluated the efficacy and safety of eptinezumab [29]. This study was approved by the independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each study site (Supplemental Table 1). All clinical work was conducted in compliance with current good clinical practices, International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines, local regulatory requirements, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients enrolled in the study provided written informed consent before participating.

The total study duration was 32 weeks, with 10 scheduled visits (screening, day 0, and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 32), where 1072 adults with CM were randomly assigned to receive IV eptinezumab 100 mg, 300 mg, or placebo administered over 30 min on day 0 and week 12. Participants were 18–65 years old, inclusive, with a diagnosis of migraine at ≤ 50 years of age and a history of CM ≥ 12 months (ICHD-3 beta criteria) [30]. Patients completed the headache electronic diary (eDiary) on ≥ 24 of the 28 days after the screening visit and before randomization. During the 28-day screening period, patients experienced ≥ 15 to ≤ 26 headache days and ≥ 8 migraine days. Those participants taking prescription or over-the-counter medication for acute or preventive treatment of migraine were eligible only if the medications had been prescribed or recommended by a health care provider. In addition, migraine preventive medication use had to be stable for ≥ 3 months prior to screening. Participants using barbiturates or prescription opioids ≤ 4 days per month were eligible for participation if use was stable for ≥ 2 months prior to screening and through week 24 of the study. Use of other acute headache medications (e.g., triptans, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, simple analgesics) was not restricted.

Outcomes and Assessments

Participants completed a daily eDiary from the time of screening through week 24 regardless of whether a headache occurred and reported any headache events and acute medication use. A headache day was defined as any day with a participant-reported headache lasting more than 30 min. An MMD was a day with a headache that met the chronic migraine definition as outlined by ICHD-3 beta criteria, i.e., a headache that lasted 4 h or more or 30 min to 4 h and was believed by the participant to be a migraine and was relieved by migraine-specific medication; exhibited at least two of the following: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity; and had at least one of the following: nausea and/or vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia [30]. MHDs were used in this analysis, as they are typically easier for participants and clinicians to define. MHDs were determined based on the results of 4-week intervals—if the headache diary was completed for ≥ 21 days of a 4-week interval, the observed frequency was normalized to 28 days. Alternatively, if the diary was completed for < 21 days of a 4-week interval, the results were a weighted function of the observed data for the current interval and the results from the previous interval, with the weight proportional to how many days the diary had been completed in the current and prior month and imputed as described in the primary analysis [29]. For endpoints captured at a single time point (HIT-6, PGIC, MBS), all available data were used. For the acute medication days endpoint, if the eDiary was completed less than 14 days within a month, the data for that month were not used.

The primary efficacy endpoint for PROMISE-2 was the change from baseline in MMDs over weeks 1–12, quantified using eDiary data. The key secondary endpoints were ≥ 75% reduction in MMDs over weeks 1–4 (i.e., ≥ 75% migraine responder rate), ≥ 75% reduction in MMDs over weeks 1–12, ≥ 50% reduction in MMDs over weeks 1–12, the percentage of patients with a migraine on the day after dosing, change from baseline in daily migraine prevalence from baseline to week 4, and acute headache medication use during weeks 1–12.

To assess a participant’s impression of change in disease status since the start of the study, the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) was administered at weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 32. PGIC included a single question and incorporated multiple domains of health, including activity limitations, symptoms, emotions, and overall quality of life. Responses on the 7-point Likert scale ranged from “very much improved” to “very much worse.”

During the screening visit, participants were asked to verbally characterize the most bothersome symptom that they associated with CM [31]. This question was open-ended, and there were no limits about the type of migraine-associated symptom, the specific migraine attack (e.g., most recent), or the specific phase of migraine attack. From the patient’s description, the study investigator grouped the patient-identified most bothersome symptom (PI-MBS) into one of nine predefined categories: nausea, vomiting, photophobia, phonophobia, fatigue, pain with activity, mood changes, or other/specify. At baseline (day 0), the PI-MBS was confirmed and was reassessed at weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24, and 32 using a Likert scale ranging from very much improved to very much worse, a scale identical to that used for PGIC to assess change in their identified most bothersome symptom.

Acute headache medication days—defined as the number of days with any acute medication use (days with any triptan, ergotamine, simple analgesic, combination analgesic [combination of drugs of different classes acting as analgesics or adjuvants], or opioid use as documented in the eDiary)—were aggregated to establish a 4-week estimate for the screening phase for the two post-treatment intervals (weeks 1–12; weeks 13–24).

To measure the impact of migraine on the ability to function normally in daily life, HIT-6 was administered at screening, on day 0, and at weeks 4, 12, 16, 24, and 32. HIT-6 includes six items—severe pain, social limitations, role limitations, cognitive functioning (4-week recall), psychological distress (4-week recall), and vitality (4-week recall)—using a Likert scale of frequency: never (6), rarely (8), sometimes (10), very often (11), and always (13). The specific questions were as follows: (1) “When you have headaches, how often is the pain severe?”; (2) “How often do headaches limit your ability to do usual daily activities including household work, work, school, or social activities?”; (3) “When you have a headache, how often do you wish you could lie down?”; (4) “In the past 4 weeks, how often have you felt too tired to do work or daily activities because of your headaches?”; (5) “In the past 4 weeks, how often have you felt fed up or irritated because of your headaches?”; and (6) “In the past 4 weeks, how often did your headaches limit your ability to concentrate on work or daily activities?” The total score for the HIT-6 is calculated from summing individual items (score range of 36–78 points), with score ranges representing severe impact = ≥ 60, substantial impact = 56–59, some impact = 50–55, and little to no impact = ≤ 49; a 6-point decrease is considered clinically meaningful in patients with CM [29, 32].

Statistical Analysis

While differences in reductions of MHD exist between treatment groups, the purpose of this post hoc analysis was to evaluate a threshold of headache days to act as a clinically meaningful treatment target rather than to examine treatment differences when that threshold is achieved; thus, all patients receiving eptinezumab 100 mg, 300 mg, or placebo were pooled for this analysis. All available data points for HIT-6 total score, PGIC, PI-MBS, and days of acute medication use were combined for weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 (i.e., post-baseline) and analyzed by the following subgroups after their first study dose based on their MHDs in the previous 4 weeks: 0–4 (super response); 5–9 (moderate response); 10–15 (marginal response); > 15 (poor response). A “patient-month” corresponded to the 4-week study intervals (months 1–6). All analyses were conducted using SAS software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) version 9.2 or higher. No statistical power calculations were conducted, and all available data were used for this analysis. Due to the post hoc nature of this analysis, no formal statistical testing was performed.

Results

Study Population

A total of 1072 participants received treatment in PROMISE-2 (eptinezumab 100 mg, n = 356; eptinezumab 300 mg, n = 350; placebo, n = 366) and were included in the pooled analysis population. The majority of participants included in this analysis received two study infusions (eptinezumab 100 mg 95.5% [340/356], 300 mg 96.6% [338/350], placebo 93.4% [342/366]). Patient disposition, as well as detailed demographic and baseline clinical characteristics, has been published previously [29]. The mean age of patients at migraine diagnosis was 22.5 years, and the mean duration of chronic migraine was 18.1 years. Forty-five percent of the cohort (479/1072) had stable concomitant prophylactic medication use; the most frequently reported medication used in > 10% of patients was topiramate (14.5%). Overall, the use of concomitant prophylactic medication was well balanced across treatment groups, with no clinically relevant differences regarding the drug dosing level, likely because the current use of prophylactic medication in these patients was not effective in reducing headache frequency below 15 days per month. In addition, 40.2% (431/1072) were dually diagnosed with CM and MOH at baseline. Because results from multiple post-baseline weeks were used for patients, the number of 4-week study intervals used in this analysis varied from 4080 for HIT-6 to just over 6100 for the PI-MBS and PGIC endpoints.

Percentage of Patients with ≤ 4 MHDs by Study Month

The percentage of patients reporting ≤ 4 MHDs at month 1 was 12.9% (46/356) and 16.3% (57/350) for patients treated with 100 mg and 300 mg eptinezumab compared to 3.8% (14/366) receiving placebo (Fig. 1). By month 6, 24.7% (88/356) and 34.9% (122/350) of patients treated with eptinezumab reported ≤ 4 MHDs, compared to 21.9% receiving placebo (Fig. 1).

Patient Global Impression of Change by Monthly Headache and Migraine Day Groups

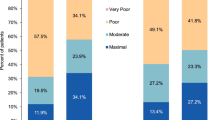

Of the patient-months (months 1–6) with ≤ 4 MHDs, on average, 40.9% (515/1258) and 44.8% (564/1258) were associated with very much improved or much improved PGIC, respectively (Fig. 2A, B). In contrast, on average, 22.9% (324/1415), 10.4% (158/1517), and 3.2% (62/1936) of patient-months with 5–9, 10–15, and > 15 MHDs, respectively, reported very much improved PGIC, and 47.0% (665/1415), 36.5% (553/1517), and 16.2% (314/1936) reported much improved PGIC (Fig. 2A, B). Patient-months with ≤ 4 MMDs followed a similar pattern, where more patients in this group were associated with very much or much improved PGIC responses (31.6% [747/2366] or 46.4% [1098/2366]).

PGIC by monthly headache day subgroupsa (A) and 0–28 monthly headache days (B) based on pooled treatment arms (eptinezumab 100 mg, eptinezumab 300 mg, and placebo for weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 combined). PGIC Patient Global Impression of Change. aMonthly headache days were stratified into subgroups after the first dose of eptinezumab based on their monthly headache days in the previous 4 weeks; a patient-month corresponded to the 4-week study intervals

Patient-Identified Most Bothersome Symptom by Monthly Headache and Migraine Day Groups

Of the patient-months (months 1–6) with ≤ 4 MHDs post-baseline (weeks 1–24), on average, 41.5% (523/ 1260) and 43.6% (549/1260) were associated with very much improved and much improved PI-MBS, respectively (Fig. 3A, B). In contrast, on average, 23.4% (331/1416), 10.8% (164/1515), and 3.5% (67/1937) of patient-months with 5–9, 10–15, and > 15 MHDs, respectively, reported very much improved PI-MBS, and 44.3% (627/1416), 33.1% (502/1515), and 14.0% (271/1937) reported much improved PI-MBS (Fig. 3A, B). Patient-months with ≤ 4 MMDs followed a similar pattern, where more patients in this group were associated with very much or much improved PI-MBS (32.9% [780/2368] or 43.4% [1028/2368]).

PI-MBS by monthly headache day subgroupsa (A) and 0–28 monthly headache days (B) based on pooled treatment arms (eptinezumab 100 mg, eptinezumab 300 mg, and placebo for weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 combined). PI-MBS patient-identified most bothersome symptom. aMonthly headache days were stratified into subgroups after the first dose of eptinezumab based on their monthly headache days in the previous 4 weeks; a patient-month corresponded to the 4-week study intervals

Acute Medication Use Days by Monthly Headache and Migraine Day Groups

During the baseline period, 50.2% (9291/18,504) and 48.1% (4594/9560) of eDiary days in the eptinezumab (100 mg and 300 mg combined) and placebo groups, respectively, reported headache with acute medication use, compared to 25.1% (25,245/100,390, eptinezumab) and 31.1% (15,755/50,632, placebo) of eDiary days post-baseline with both headache and acute medication use (Fig. 4A). Similarly, 41.9% (7744/18,504) of patients receiving eptinezumab reported migraine with acute medication use compared to 18.4% (18,447/100,390) post-baseline. Patient-months with patients reporting ≤ 4, 5–9, 10–15, and > 15 MHDs reported acute medication use for ≥ 10 days in, on average, 1.9% (21/1111), 4.9% (63/1267), 49.5% (670/1351), and 74.1% (1232/1662) of patient-months, respectively (Fig. 4B, C). Comparatively, patients reporting ≤ 4 MMDs reported acute medication use for ≥ 10 days in 10.9% (228/2109) of patient-months.

Distribution of days with and without headache and acute medication by treatment (A), by monthly headache day subgroupsa (B), and by 0–28 monthly headache days (c). AHM acute headache medication use. aMonthly headache days were stratified into subgroups after the first dose of eptinezumab based on their monthly headache days in the previous 4 weeks; a patient-month corresponded to the 4-week study intervals. Data for weeks 4, 8, 12, 20, and 24 are combined

Importantly, on average, 96.1% (1068/1111) of patients with ≤ 4 MHDs reported ≤ 4 acute medication use days, compared to 13.7% (227/1662) of patients with > 15 MHDs. Similarly, a large proportion (69.0% [1456/2011]) of patients with ≤ 4 MMDs reported ≤ 4 acute medication use days. Overall, there were very few days on which patients in either treatment group did not take acute medication for a headache (1.7% [313/18,504] for eptinezumab and 2.9% [1483/50,632] for placebo); thus, patients with few headache days had few acute medication use days.

Headache Impact Test Score by Monthly Headache and Migraine Day Groups

Of the post-baseline patient-months with ≤ 4 MHDs, on average, 37.1% (308/830) and 30.5% (253/830) were associated with little to none or some HIT-6 impairment, respectively (Fig. 5A, B). In contrast, on average, 19.9% (187/940), 10.1% (101/999), and 3.7% (49/1311) of patient-months with 5–9, 10–15, and > 15 MHDs, respectively, reported little to none HIT-6 impairment, and 27.7% (260/940), 18.1% (181/999), and 9.1% (119/1311) reported some HIT-6 impairment (Fig. 5A, B). Similarly, 31.5% (494/1566) and 30.5% (478/1566) of patients with ≤ 4 MMDs were associated with little to none or some HIT-6 impairment.

HIT-6 score by monthly headache day subgroupsa (A) and 0–28 monthly headache days (B) based on pooled treatment arms (eptinezumab 100 mg, eptinezumab 300 mg, and placebo for weeks 4, 12, 16, and 24 combined). HIT-6 6-Item Headache Impact Test. aMonthly headache days were stratified into subgroups after the first dose of eptinezumab based on their monthly headache days in the previous 4 weeks; a patient-month corresponded to the 4-week study intervals

Discussion

Overall, migraine is a heterogeneous disease with a substantial burden of illness having the greatest impact during prime-earning and family-building years [7, 33, 34]. However, current standards take a time-consuming, one-size-fits-all approach to target treatment and disease prevention and are often difficult to consistently implement clinically. Further, these abstruse treatment targets impede a clear and collaborative dialogue between patients and clinicians. Specifically, the current care paradigm incorporates multiple variables that are often difficult for patients to track, potentially impeding a clinician’s ability to individualize, set, reach, and maintain treatment goals or targets. Together, the current treatment paradigm often leaves patients and clinicians confused and often dissatisfied with clinical outcomes [12]. Although the AHS defines a migraine preventive goal as a ≥ 50% reduction in MMDs [12], a 50% reduction in MMDs to a patient with a high or variable number of migraine days is still associated with significant migraine-related burden, as well as burden related to non-migraine headache [16]. For example, a patient initiating treatment with 14 MMDs and reporting a 50% reduction in MMDs is still experiencing 7 MMDs with an unknown change in overall headache burden. This burden also may preclude patients from keeping accurate headache diaries, such as recording each headache or migraine event, distinguishing headache and migraine characteristics, or characterizing other burden associated with headache and migraine. In addition, unlike clinical trials, a baseline number of headache / migraine days is rarely established by clinicians before preventive treatment is initiated, and rarer yet, reestablished before new treatments are initiated. Percentage-based treatment targets are often difficult to verify and assess if they are a result of treatment. Thus, there is a need to develop a standardized treatment target for patients with CM that is easily understood and simple to measure.

Overall, data from this post hoc pooled analysis of PROMISE-2 support the use of ≤ 4 MHDs as a treatment target for patients with CM. Specifically, participants in PROMISE-2 who achieved 0–4 MHDs in the prior 4 weeks had a higher percentage of patients reporting very much improved and much improved on the PI-MBS, little to none or some HIT-6 impairment, and very much improved PGIC. While there was no major inflection point differentiating PGIC scores of the ≤ 4 MHD subgroup relative to the 5–9 subgroup, there is an overall clear relationship between headache frequency and PGIC score, demonstrating the clinical usefulness of this measure. These data support the idea that no individual PRO measure captures the full embodiment of a patient’s migraine disease [20]. Further, participants in the ≤ 4 MHD subgroup reported the lowest percentages of patient-months with > 15 acute headache medication days. Finally, the use of acute medication paralleled headache frequency, suggesting additional benefits to helping patients reach ≤ 4 MHDs. MHDs were selected for this analysis, as MHDs are easier for patients and clinicians to define; MMD data exhibited similar trends in PRO outcomes to those described for MHDs.

Moving forward, a preventive treatment target needs to include guidance to help patients reach ≤ 4 MHDs rather than focusing solely on a 50% reduction in MMDs. Having clearly articulated treatment targets that are easier to define (e.g., assessing headache days vs. migraine days) will help improve communication between patients and health care providers and clarify meaningful treatment outcomes. Overall, having a more clearly defined treatment target will aid the clinical care of patients and simplify an increasingly burdensome process, particularly for non-headache specialists, in terms of a diagnostic definition for CM and MOH.

Limitations

Ultimately, treatment targets in practice will be determined by a cost–benefit analysis for an individual patient. When we examine the relationship of MHD frequency to outcome measures, there is a clear gradient and not an absolute cut-score. If a patient’s headache burden decreases from 20 to 5 MHDs, they respond well to acute treatment and are functioning well, adding another preventive medication may produce side effects that outweigh the benefits of a 1-day reduction in MHDs. The treatment target of 4 MHDs is a target, but patient outcomes, as always, need to be individualized.

Because questions 1, 2, and 3 of the HIT-6 are general questions not time-bound to the previous 4 weeks, these responses may impact interpretation of the impact of MHDs on HIT-6 [32]. Specifically, in the MHD 0–4 patient-response group, 53%, 44%, and 84% of participants responded very often or always to questions 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Question 1 asks the patient to rate pain severity, when they have a headache; question 2 asks how often headaches limit usual activities; and question 3 asks when they have a headache, how often the patient wishes to lie down.

Data for this post hoc analysis were pooled across treatment arms (eptinezumab-treated and placebo) and included repeat measures from individuals; additional prospectively designed trials are required to confirm these findings. In addition, based on the demographic characteristics that were reported in the full study population (i.e., predominantly white and non-Hispanic), the results may not be generalizable to all patients with CM, with further research warranted in more racially and ethnically diverse patient groups. To increase diversity in clinical trials, several approaches—including utilizing focused patient inclusion criteria, ensuring diversity of clinical trial sites and investigators, removing barriers that could impede the participation of certain groups in clinical trials, and using real-world data to improve the understanding of diseases—can be used. Ensuring care equity will help increase quality of life for all of those who suffer from migraine. Finally, because this current analysis is limited to clinical data from PROMISE 2, additional analyses are required to further understand the clinical utility of a headache number threshold in improving patient–clinician dialogue and patient outcomes.

Conclusion

In this post hoc analysis, participants improving to ≤ 4 MHDs achieved superior patient-reported outcomes with the least acute medication use, suggesting that 4 MHDs may be a useful therapeutic target to be used by health care providers and patients with CM. Implementation of a therapeutic target number into clinical practice may aid clinicians (especially non-headache specialists) manage their headache population by providing a single simple-to-communicate treatment target for chronic migraine in addition to improving understanding and communication between patients and health care providers.

References

GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:954–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30322-3.

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417738202.

Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Lipton RB, et al. Assessment of migraine disability using the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire: a comparison of chronic migraine with episodic migraine. Headache. 2003;43:336–42. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03068.x.

Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine in the population: burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology. 2008;71:559–66. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000323925.29520.e7.

Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31:301–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102410381145.

Serrano D, Lipton RB, Scher AI, et al. Fluctuations in episodic and chronic migraine status over the course of 1 year: implications for diagnosis, treatment and clinical trial design. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:101. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0787-1.

Cady RK, Schreiber CP, Farmer KU. Understanding the patient with migraine: the evolution from episodic headache to chronic neurologic disease. a proposed classification of patients with headache. Headache. 2004;44:426–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04094.x.

Buse DC, Greisman JD, Baigi K, Lipton RB. Migraine progression: a systematic review. Headache. 2019;59:306–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13459.

Young WB, Park JE, Tian IX, Kempner J. The stigma of migraine. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e54074. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0054074.

Houts CR, McGinley JS, Wirth RJ, et al. Reliability and validity of the 6-item Headache Impact Test in chronic migraine from the PROMISE-2 study. Qual Life Res. 2021;30:931–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-020-02668-2.

Ailani J, Burch RC, Robbins MS. The American Headache Society Consensus Statement: update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2021;61:1021–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14153.

US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration (2018) Migraine: Developing Drugs for Acute Treatment Guidance for Industry. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/default.htm. Accessed 27 Mar 2022

American Headache Society. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13456.

Silberstein SD. Preventive migraine treatment. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21:973–89. https://doi.org/10.1212/CON.0000000000000199.

Cady R, Lipton RB. Qualitative change in migraine prevention? Headache. 2018;58:1092–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13354.

Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second international burden of migraine study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013;53:644–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12055.

Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37:470–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102416678382.

van Casteren DS, Verhagen IE, de Boer I, et al. E-diary use in clinical headache practice: a prospective observational study. Cephalalgia. 2021;41:1161–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/03331024211010306.

Alpuente A, Gallardo VJ, Caronna E, et al. In search of a gold standard patient-reported outcome measure to use in the evaluation and treatment-decision making in migraine prevention. A real-world evidence study. J Headache Pain. 2021;22:151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01366-9.

Haywood KL, Mars TS, Potter R, et al. Assessing the impact of headaches and the outcomes of treatment: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1374–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102417731348.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–79. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0413.

Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: a Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:E1082–143. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000625.

Al-Makki A, DiPette D, Whelton PK, et al. Hypertension pharmacological treatment in adults: a world health organization guideline executive summary. Hypertension. 2022;79:293–301. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18192.

(2022) Vyepti [package insert]. Bothell, WA, Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals, Inc.

Lundbeck A/S Valby D (2021) Vyepti [EMA Authorization]. Valby, Denmark

Lundbeck Canada Inc. (2021) Product Monograph Including Patient Medication Information: Vyepti (Eptinezumab for injection)

Ashina M, Saper J, Cady R, et al. Eptinezumab in episodic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (PROMISE-1). Cephalalgia. 2020;40:241–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102420905132.

Lipton RB, Goadsby PJ, Smith J, et al. Efficacy and safety of eptinezumab in patients with chronic migraine: PROMISE-2. Neurology. 2020;94:e1365–77. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009169.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102413485658.

Lipton RB, Dodick DW, Ailani J, et al. Patient-identified most bothersome symptom in preventive migraine treatment with eptinezumab: a novel patient-centered outcome. Headache. 2021;61:766–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14120.

Houts CR, Wirth RJ, McGinley JS, et al. Determining thresholds for meaningful change for the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) total and item-specific scores in chronic migraine. Headache. 2020;60:2003–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13946.

Agosti R. Migraine burden of disease: from the patient’s experience to a socio-economic view. Headache. 2018;58:17–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13301.

Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML, et al. Life with migraine: effects on relationships, career, and finances from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) Study. Headache. 2019;59:1286–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13613.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants included in the study.

Funding

This analysis and journals fees were sponsored and funded by Lundbeck LLC. The sponsor participated in the design and conduct of the study; data collection, management, analysis, and interpretation; and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. All statistical analyses were performed by a contracted research organization and were directed or designed by Pacific Northwest Statistical Consulting under contractual agreement with Lundbeck Seattle BioPharmaceuticals, Inc. All authors and Lundbeck LLC reviewed and approved the manuscript and made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Editorial support for the development of this manuscript was funded by Lundbeck LLC.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors thank Beth Reichard, PhD, Philip Sjostedt, BPharm, and Nicole Coolbaugh, CMPP, of The Medicine Group, LLC (New Hope, PA, USA) for providing medical writing support, which was funded by Lundbeck LLC (Deerfield, IL, USA) in accordance with good publication practice guidelines. In addition, the authors would like to thank Richard Lipton, MD, for contributing to data interpretation and manuscript development.

Author Contributions

Robert G. Kaniecki, Deborah I. Friedman, Divya Asher, and Roger Cady contributed to the conception and design of the study. Joe Hirman performed the statistical analyses, and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. All authors reviewed and provided critical revision of all manuscript drafts for important intellectual content, and read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Prior Presentation

While findings from this manuscript have been presented in part at scientific congresses, none of the pooled outcomes that are covered in this manuscript have been previously published or posted.

Disclosures

Robert G. Kaniecki has no disclosures to report. Deborah I. Friedman serves on advisory boards for AbbVie, Axsome, Eli Lilly, Impel, Lundbeck, Revance, Theranica, and Satsuma. She serves on the speakers’ bureau for Impel and AbbVie. She received grant support from Allergan, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Zosano. She is a consultant for Supernus, Linpharma Inc., and Lundbeck. She receives honoraria for serving as a contributing author to MedLink Neurology and Medscape and as a member of the Editorial Board of Neurology Reviews and Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. She is no longer affiliated with the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Divya Asher is a full-time employee of Lundbeck LLC. Joe Hirman is an employee of Pacific Northwest Statistical Consulting, Inc., a contracted service provider of biostatistical resources for H. Lundbeck A/S. Roger Cady was a full-time employee of Lundbeck or one of its subsidiary companies at the time of the original study.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Approval for this study was provided by the independent ethics committee or institutional review board of each of the 145 study sites (Supplemental Table 1). The PROMISE-2 study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, standards of Good Clinical Practice as defined by the International Conference on Harmonisation, and all applicable federal and local regulations. All study documentation was approved by the local review board at each site or by a central institutional review board or ethics committee. Patients provided written informed consent prior to initiation of any study procedures. Consent for publication is not applicable.

Data Availability

In accordance with EFPIA’s and PhRMA’s Principles for Responsible Clinical Trial Data Sharing guidelines, Lundbeck is committed to responsible sharing of clinical trial data in a manner that is consistent with safeguarding the privacy of patients, respecting the integrity of national regulatory systems, and protecting the intellectual property of the sponsor. The protection of intellectual property ensures continued research and innovation in the pharmaceutical industry. Deidentified data are available to those whose request has been viewed and approved through an application submitted to https://www.lundbeck.com/global/our-science/clinical-data-sharing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaniecki, R.G., Friedman, D.I., Asher, D. et al. Improving to Four or Fewer Monthly Headache Days Per Month Provides a Clinically Meaningful Therapeutic Target for Patients with Chronic Migraine. Pain Ther 12, 1179–1194 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00525-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00525-x