Abstract

Introduction

A modified Delphi strategy was implemented for obtaining recommendations that could be useful in the management of percutaneous radiofrequency treatment of lumbar facet joint syndrome, as the literature on the argument was poor in quality.

Methods

An Italian research team conducted a comprehensive literature search, defined the investigation topics (diagnosis, treatment, and outcome evaluation), and developed an explorative semi-structured questionnaire. They also selected the members of the panel. After an online meeting with the participants, the board developed a structured questionnaire of 15 closed statements (round 1). A five-point Likert scale was used and the cut-off for consensus was established at a minimum of 70% of the number of respondents (level of agreement ≥ 4, agree or strongly agree). The statements without consensus were rephrased (round 2).

Results

Forty-one clinicians were included in the panel and responded in both rounds. After the first round, consensus (≥ 70%) was obtained in 9 out of 15 statements. In the second round, only one out of six statements reached the threshold. The lack of consensus was observed for statements concerning the use of imaging for a diagnosis [54%, median 4, interquartile range (IQR) 3–5], number of diagnostic blocks (37%, median 4, IQR 2–4), bilateral denervation (59%, median 4, IQR 2–4), technique and number of lesions (66%, median 4, IQR 3–5), and strategy after denervation failure (68%, median 4, IQR 3–4).

Conclusion

Results of the Delphi investigations suggest that there is a need to define standardized protocols to address this clinical problem. This step is essential for designing high-quality studies and filling current gaps in scientific evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Lumbar facets radiofrequency neurolysis is a frequently used technique and represents one of the most debated interventions. For these reasons, we decided to provide an expert consensus to clarify the different processes of the technique and to contextualize the international recommendations to the Italian reality. |

Given the variability in the management approaches identified in this study, some important areas for future research were developed. |

Our results suggest that there is also a need to define standardized protocols when performing a radiofrequency procedure. |

The areas of expert agreement are summarized in the central illustration (Fig. 4), which we suggested as a leading element of this paper. |

Introduction

The diagnosis of lumbar facet joint disease is prevalent in up to 45% of patients with low back pain [1]. The disease is often treated with lumbar facet joint denervation with the use of continuous radiofrequency [lumbar facets radiofrequency neurolysis (LFRN)]. Notably, in the USA, LFRN represents the second most common procedure performed in interventional pain practice [2] and, from 2009 to 2018, costs for this treatment have more than doubled [3]. The technique of sensory branch ablation of the dorsal ramus to denervate the facet joint has significantly evolved with the improvements in pathophysiological understandings and surgical technology. In 1918, Vincent Nesfield described for the first time the denervation technique using an ophthalmic scalpel to directly cut the nerve [4]. The famous neurosurgeon Norman Shealy improved this technique with the use of fluoroscopy to target the medial branch of the facet joint. Eventually, Don Long modified Shealy’s technique into the form we still use today [5, 6].

Despite the increasing use of LFRN, it is one of the most debated interventions [2, 7] and all aspects of the technique, including diagnostic criteria, patient selection, technical methodology and postprocedural management, remain controversial [7].

Recently, a multispecialty international working group addressed the matter and released consensus-based guidelines [7]. The project involved 12 national and international societies and different government agencies. Nevertheless, the authors concluded that the evidence, although growing, is still insufficient to comprehensively address the procedure. They also stated that their “guidelines should not be misconstrued as unalterable standards, nor can they account for every possible variation in presentation or treatment circumstance.”

Therefore, this important gap in the available literature should be filled. The scientific literature on this topic is represented by monocentric studies with low sample sizes and an uncontrolled design. Moreover, the major limitation is that they provide results on different techniques.

The lack of high-quality evidence due to the realities of clinical practice represent serious obstacles to the standardization of the work procedure [8]. Furthermore, the cost of the disease and the distribution of resources for interventional procedures vary geographically [9]. Undoubtedly, these variables may impact the therapeutic pathways adopted.

On these premises, an Italian group of experts aims to define the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway for the treatment of LFRN. The final outcome would be to provide consensus and clarify the different processes of the technique, contextualizing the international recommendations to the Italian reality.

Methods

A two-round modified Delphi strategy was implemented. The Delphi method is a widely adopted group consensus strategy. It is applied to achieve agreement where there is no consensus or agreement on the interventions and/or solutions to be adopted [10]. After the identification of the topic, the board (research team) carried out a comprehensive literature search. A member of the research team (F.O.) was the moderator. He designated an expert in Delphi approaches and survey strategies for establishing the proper methodology to be followed (M.C.).

Based on the literature review and clinical experience, the research team defined the topics and developed an explorative semi-structured questionnaire.

The members of the panel were selected by the research team according to their specialty (pain medicine, anesthesiology, interventional radiology, neurosurgery), scientific background, and activity for scientific societies. In particular, the inclusion criteria were:

-

Active involvement in the management of patients with pain (have worked in a pain therapy center or performed pain relief procedures), for at least 5 years.

-

Used continuous radiofrequency, mainly for performing denervation of the lumbar joint facets, for at least 5 years.

-

Performed at least 50 cases/year of lumbar facet joint denervation.

-

Performed lumbar facet joint denervation for at least 5 years.

-

Active involvement in research project on facet joint denervation techniques or with previously published articles or abstracts on this topic.

Forty-one physicians were selected. All participants agreed to participate in the survey and signed an informed consent. An online meeting was held in June 2022. This first meeting was aimed at presenting the purpose of the investigation and at identifying the key topics.

Based on the discussion, the board developed a structured questionnaire according to the BRUSO (brief, relevant, unambiguous, specific, and objective) model [11]. The questionnaire encompassed 15 closed statements divided into three relevant areas of interest:

-

Diagnosis (5 statements),

-

Technical aspects (6 statements),

-

Outcome evaluation (4 statements).

The structured questionnaire is reported in Table 1.

Internet technologies were used to facilitate the Delphi procedure (e-Delphi) [12]. Consequently, the panelists received an email invitation to participate in the study and to complete rounds of the questionnaire. In each round, anonymous electronic surveys were used to collect the data via Google Form. The panelists received a link to access the questionnaires and Google Drive (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA) was used to store the experts’ answers. Non-responders were sent two electronic reminders.

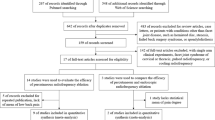

For the agreement, a five-point Likert scale (1: strongly disagree, 2: disagree, 3: partially agree, 4: agree, 5: strongly agree) was implemented. The cutoff for consensus was set at a minimum of 70% of the number of respondents with a level of agreement ≥ 4 (agree or strongly agree). Statements that reached the threshold were included in the final recommendations. The statements that did not reach the cutoff were rephrased, and a second Delphi round was started with the same rules as the first. As Diamond et al. [13] suggested, the stability criterion was not assumed as a closing rule. Thus, two rounds were fixed as a closing criterion. Finally, after the second round, an analysis of consensus with data processing was performed and a closing online meeting was held (Fig. 1).

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study. This Delphi survey did not investigate therapies or pathologies relating to the individual patient. It also did not collect sensitive, personal, or clinical data. For all these reasons, according to the Italian current legislation for non-interventional or observational studies (Ministerial Circular N. 6,2 September 2002), it is only necessary to submit a survey for approval by an Ethics Committee if the following criterion was met: “the study focused on problems or pathologies in the within which medicinal products are prescribed in the usual way in accordance with the conditions set out in the marketing authorization. The inclusion of the patient in a specific therapeutic strategy is not decided in advance by the trial protocol but is part of normal clinical practice and the decision to prescribe the medicine is completely independent from that of including the patient in the study.”

Results

The Delphi survey encompassing the preliminary step and two rounds (first and second Delphi rounds) was conducted between July and September 2022 and, as previously reported, a total of 41 clinicians were included in the panel. The respondent rate of the first and second round was 100% (41 physicians involved). The demographic data of the participants involved in the expert panel are reported in Table 2.

After the first Delphi round, 60% (9/15) of the statements reached the cutoff value for the consensus (70% agreement ≥ 4), (Fig. 2).

Consequently, the six statements that did not reach the consensus were reformulated for the second round (Table 3).

In the second round, four out of six statements increased the percentage of agreement, while the consensus was achieved for only statement number 7 (18G curved needle with 10 mm active tip). The lack of consensus was observed for the statement number 2 (radiological imaging), statement number 3 (number of diagnostic medial branch blocks), statement number 6 (bilateral denervation), statement number 11 (technique and number of lesions), and statement number 15 (strategy after denervation failure) (Fig. 3).

The comparative agreement rate in the first and second Delphi rounds with median and interquartile range are reported in the appendix (Appendix, Fig. 1) along with the statements table with agreement rates and confidence intervals (Appendix, Table 1).

Discussion

In this national Delphi consensus study, the diagnostic and therapeutic pathways for lumbar facet joint radiofrequency denervation were investigated. Notably, some areas of expert agreement (central illustration), along with some controversies, were identified.

Diagnosis

In the field of diagnosis, expert agreement was high regarding the clinical presentation and physical examination of patients with suspected facet joint syndrome (statement 1: 98% agreement). Conversely, the need to perform a neuroimaging study only to exclude red flags and not make the diagnosis of lumbar facet joint syndrome did not reach an agreement among participants (statement 2: 61% first round agreement, 54% second round agreement). Instrumental examinations are not an essential step for the diagnosis of facet joint syndrome, since there are no effective correlations between clinical symptoms and degenerative spinal changes [14]. Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) was suggested as the best imaging modality to detect potentially painful facet joints since it can identify the presence of active inflammation affecting the facet joint and provides detailed physiological information [15]. In fact, as reported by Jain et al. [16], patients with inflammatory involvement of facet joints confirmed by positive SPECT had a positive facet joint nerve block in 71% of cases compared with 43% of negative SPECT. Unfortunately, SPECT involves the use of a radioactive tracer with possible allergic reactions along with radiation exposure (gamma rays) by radioactive isotopes. Weak evidence exists supporting the routine use of SPECT for identifying painful lumbar facet joints, and further studies are required to assess its cost-effectiveness.

In two previously published studies, no association was found between facet joint involvement on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and denervation results [17, 18]. However, our analysis shows that many pain physicians still require lumbar spine imaging for the diagnosis of low back pain without a clear indication, probably with the aim to reassure their patients and themselves or to meet patients’ expectations. In fact, the increased number of MRI investigations is associated with higher rates of spine surgery, without a clear improvement in patient outcome [19, 20].

The number of medial branch (MB) nerve blocks and the technical notes to perform the block did not reach agreement among participants (statement 3: 51% first round agreement, 37% second round agreement). In fact, the panel showed different and conflicting opinions regarding the type of local anesthetic to use, the number of diagnostic MB blocks to perform and the interval between each diagnostic block before the denervation. The accuracy of a diagnostic block depends on several technical and anatomical factors and the aim of the procedure is to provide a selective block of the MB of the dorsal rami [21]. Unfortunately, MB nerve blocks are unlikely to achieve this accuracy due to the proximity of the intermediate and lateral branches of the dorsal rami, resulting in a potential non-selective neural blockade [22]. Since the MB innervates both the multifidus, the interspinal muscle, the ligament and the periosteum of the neural arch [23], a more protective approach would be to offer dual diagnostic MB blocks. This approach is associated with a higher success rate for LFRN and the diagnostic accuracy is improved if lidocaine and bupivacaine are used in two separate blocks [7]. However, it is well known that diagnostic MB blocks are frequently associated with a high false-positive rate [24] and some studies supported the presence of aberrant facet joint innervation [25]. On the contrary, as it was recently proposed, even a single MB block could be sufficient before LFRN [26].

Theoretically, a diagnostic intraarticular (IA) facet joint block could be more specific to avoid other anatomical structures. However, the diagnostic IA facet joint block cannot be suggested since it is less predictive than MB block for the outcome of LRFN, as reported in the Facet Treatment Study (FACTS) [27] and it is characterized by a higher technical failure rate [22, 28]. Some panelists suggested the use of steroids when performing a diagnostic IA facet joint block to increase the pain relief of the block. In our opinion, IA facet joint block is useful only in select populations where inflammation can be considered as a key characteristic of the disease, such as in rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis. Therefore, the use of steroids is discouraged. On the contrary, some conditions should be treated with IA facet joint blocks since LFRN could be contraindicated. For example, in case of spondylolisthesis, the theoretical paravertebral muscle atrophy after LFRN can adversely impact this condition [29, 30]. Moreover, individuals with implantable cardioverter defibrillators or pacemaker-dependent patients can be at risk for complications during LFRN [31, 32], and a more conservative approach should be considered.

A substantial agreement was obtained for the use of ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance to perform MB blocks with a small volume (≤ 0.5 ml) of local anesthetic at a maximum of three vertebral levels to reduce the spread to adjacent structures (statement 4: 78% first round agreement). In fact, as it was previously reported, a selective block with a small amount of local anesthetic is mandatory to increase the specificity of the block and to avoid an aberrant spread to adjacent anatomical structures [33]. The panelists suggested a 70% pain reduction to designate the block as “positive” and to increase its specificity (statement 5: 80% first round agreement).

Technical Aspects

The panelists reached consensus on the technique of placing the needle for LFRN (statement 8: 80% first round agreement). The needle should be inserted tangentially along the course of the MB to allow a longitudinal contact between the cannula and nerve. Moreover, a proper anatomical confirmation should be obtained with cranial, caudal, and lateral fluoroscopic images as it was previously reported [34].

Motor stimulation should be performed to identify multifidus or other paraspinal muscle stimulation, thus indicating the proper placement [35], and to avoid the position of the needle in close proximity to the ventral ramus or spinal nerve (statement 9: 85% first round agreement). Moreover, the presence of paravertebral muscle twitching while performing LFRN may be a reliable predictor of long-term efficacy [36].

An agreement regarding the use of a needle with adequate diameter (18G needle) with 10 mm active tip while performing a LRFN was obtained only in round two (statement 7: 61% first round agreement, 71% second round agreement). Conversely, a great controversy emerged regarding the opportunity of using a curved tip needle. The curved needle has some advantages since it allows to rotate the tip to further increase the lesion size and to hug the base of the superior articular process of the facet joint [37]. Unfortunately, the curved tip is used by only a few pain physicians in Italy and this drawback should be adequately improved.

The importance of needle diameter and the length of active tip is based on electrophysiological principles, along with technical and physical aspects of radiofrequency [21, 38, 39], as it was reported also for knee joint radiofrequency [40]. Moreover, the transverse diameter of lumbar MBs is < 2 mm and even smaller (0.5 mm) at L5 level [41]. Consequently, there is the need to enlarge the lesion size enough to increase the chance of reaching the target and to create a lesion that envelops this structure [42]. For this reason, it is suggested to use an 18G needle with 10 mm active tip, preferably with a curved tip [43].

In case of bilateral low back pain, the simultaneous denervation of both sides offers the theoretical advantage of rapidly reducing the pain. However, this advantage is counterbalanced by the potential atrophy of paravertebral muscles. Dreyfuss et al. [29], in a small observational study, found a diffuse atrophy of the lumbar multifidus when performing a lumbar MRI 17–26 months after the denervation, along with greater disc degeneration. The same findings were confirmed in a subsequent study by Smuck et al. [44], and a significant loss of paravertebral muscles, requiring stabilization, was observed after cervical MB radiofrequency denervation [45]. On the contrary, recently published articles did not confirm these findings [46]. This conflicting evidence seems related to the use of different methods to measure muscular atrophy and does not consider possible catabolic effects of injected steroids on muscle tissue [47]. New studies with adequate sample size, and especially adequate evaluation protocols for the measurement of muscular atrophy, should be developed. Despite the uncertainty of evidence and the absence of agreement among panelists, the bilateral denervation of lumbar facet joints remains an undefined topic and should be explored in appropriate studies.

A strong consensus was obtained for the injection of local anesthetic (2% lidocaine) before LRFN to reduce procedural pain (statement 10: 78% first round agreement). The panelists underlined that a specific volume of local anesthetic to prevent pain from LRFN is not definable since every patient could require a different volume. For this reason, the panelists suggested the use of 0.5 ml 2% lidocaine per level and to increase the volume by a 0.5 ml increment as required to ensure a non-painful LRFN.

No consensus was obtained for the number of lesions to perform for each MB denervation (statement 11: 51% first round agreement, 66% second round agreement). As it was previously reported, two lesions should be performed at each MB [43]. The panelists agreed to use 80 °C for 90 s to perform a LRFN, but no consensus was reached for the 90° rotation of the needle to maximize the chance of producing an effective denervation without significant risk. However, we recognize that this statement needs to be contextualized with the type of needle used (presence/absence of curved tip) and different manufacturers’ machines, which might perform differently.

Outcome Evaluation

A strong consensus was obtained for the outcome evaluation after LRFN (statement 12: 88% first round agreement) and for the 50–60% pain reduction cutoff to define the procedure as “successful” (statement 13: 88% first round agreement). In fact, the panelists agreed to consider that the evaluation of only pain intensity is insufficient to assess the patient’s outcome after LRFN, and a more comprehensive evaluation to explore the physical and social function along with the psychological distress should always be performed [48].

An adequate rehabilitation program should be implemented after LRFN since it improves the neuromuscular control, the endurance, and the strength of many muscles involved in maintenance of dynamic spinal stability [45]. Almost all the panelists considered the importance of rehabilitation programs after LRFN (statement 14: 95% first round agreement). In fact, as previously reported, the rehabilitation program can enhance the results obtained with LRFN [50].

No consensus was obtained for the management of patients with inadequate pain relief after LRFN (statement 15: 66% first round agreement, 68% second round agreement). Regarding this topic, the panelists considered it vital to promptly reconsider the diagnosis looking for other pain generators after an ineffective LRFN. However, if the facet joint pain generator is confirmed, they did not agree whether to wait 3 months before repeating the denervation, or to use a different denervation technique. The 3-month cutoff to define the success of LRFN is based on a study by Cohen et al. [51]. In fact, in that study, the patients who underwent a new LRFN before the 3-months cutoff after the first LRFN, reported a less successful outcome. In another study, Son et al. [52] performed a retrospective analysis in patients who received more than one LRFN. Even if the authors found no difference in the pain reduction of the repeated LRFN; the mean duration of the first LRFN was 10.9 months. Consequently, it is possible to argue that after a successful LRFN lasting at least 3 months it is possible to repeat the LRFN without losing its efficacy. On the contrary, if the pain reduction was insignificant or the duration of the pain relief was limited, and the reevaluation of the patient leads to a decision to repeat the treatment, a new prognostic block is discouraged since it does not play a role in the decision to repeat the LRFN [53]. It is likely that the many panelists did not completely understand statement 15, and therefore uncertainties emerged.

Study Limitations

The selection bias is a potential limitation of this study; for example, the panel was mainly composed of male participants. This is common since several prior studies highlighted that male physicians account for the majority of health-care providers in the field of pain medicine [54, 55]. Moreover, most of the included physicians were anesthesiologist (85%) from the north of Italy (53.7%). In our national context, pain therapy is a branch of anesthesia, furthermore the distribution of pain therapy centers is not uniform [56, 57].

This study used a small sample size; therefore, findings should be interpreted with caution and validated by a larger study, even though the literature suggests there is no standardized number of participants [58]. On the contrary, well-defined inclusion criteria, and especially the degree of experience of the participants, are fundamental elements for the success of a survey [59].

The results would have been more comprehensive with the inclusion of experts from other geographic domains. Nevertheless, this study was able to provide an evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the LRFN procedure in an Italian context, which is useful for planning uniform and controlled clinical pathways.

Other important limitations of the survey include the threshold (≥ 70%) and the lack of the stability rule of responses between rounds. According to the guidelines for the Delphi survey methodology, there is not a definite threshold for agreement. It depends on the number of experts, number and type of levels of agreement adopted (Likert scale) and, above all, on the topic analyzed [60]. In our investigation, the heterogeneity of diagnostic and therapeutic approaches and the lack of directives and guidelines led us to choose a threshold of 70%. Pertaining to the absence of the stability criterion, as described in Delphi literature, the balance can be established through the aggregate of judgements (analysis of individual judgements) for proceeding from a subjective level to a central tendency [61]. Another limitation of this Delphi-based study is that many of the conclusions are based on expert opinion and consistent with international guidelines.

Perspectives

This paper presents the results of the first Italian Delphi consensus study to investigate the current practices for the management of lumbar facet joint syndrome, along with the need to improve a correct use of LRFN. From our discussions with the panelists, a lack of homogeneity in diagnostic and therapeutic approaches was observed in Italy’s different pain units. In fact, the education in pain management and interventional approaches are provided by only a limited number of pain centers and universities in Italy, and this topic should be adequately improved. However, this Delphi study revealed a strong interest and a widespread use of radiofrequency among pain physicians in Italy. For this reason, it is important to systematically analyze all the denervation techniques used in our country and to develop national clinical registries to ensure quality and to improve outcomes.

Finally, a possible role of the facet joint capsule denervation should be adequately investigated as a new, possible, safe, and effective target.

Conclusions

We describe expert consensus recommendations for the management of patients with lumbar facet joint syndrome. Given the variability in the management approaches identified in this study, some important areas for future research were developed. Our results suggest that there is also a need to define standardized protocols when performing a radiofrequency procedure. The areas of expert agreement are summarized in the central illustration (Fig. 4), which we suggested as a leading element of this paper.

Change history

29 July 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00536-8

References

Starr JB, Gold L, McCormick Z, Suri P, Friedly J. Trends in lumbar radiofrequency ablation utilization from 2007 to 2016. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. 2019;19(6):1019–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2019.01.001.

Lee DW, Pritzlaff S, Jung MJ, et al. Latest Evidence-Based Application for Radiofrequency Neurotomy (LEARN): best practice guidelines from the American Society of Pain and Neuroscience (ASPN). J Pain Res. 2021;14:2807–31. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S325665.

Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Soin A, et al. Trends of expenditures and utilization of facet joint interventions in fee-for-service (FFS) medicare population from 2009–2018. Pain Physician. 2020;23(3S):S129–47.

Russo M, Santarelli D, Wright R, Gilligan C. A history of the development of radiofrequency neurotomy. J Pain Res. 2021;14:3897–907. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S334862.

Shealy CN. Facets in back and sciatic pain. A new approach to a major pain syndrome. Minn Med. 1974;57(3):199–203.

Shealy CN. Percutaneous radiofrequency denervation of spinal facets. Treatment for chronic back pain and sciatica. J Neurosurg. 1975;43(4):448–51. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1975.43.4.0448.

Cohen SP, Bhaskar A, Bhatia A, et al. Consensus practice guidelines on interventions for lumbar facet joint pain from a multispecialty, international working group. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2020;45(6):424–67. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2019-101243.

Finlayson RJ, Curatolo M. Consensus practice guidelines on interventions for lumbar facet joint pain: finding a path through troubled waters. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2020;45(6):397–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2020-101597.

Zemedikun DT, Kigozi J, Wynne-Jones G, Guariglia A, Roberts T. Methodological considerations in the assessment of direct and indirect costs of back pain: a systematic scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5): e0251406. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251406.

Nasa P, Jain R, Juneja D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: How to decide its appropriateness. World J Methodol. 2021;11(4):116–29. https://doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v11.i4.116.

Peterson R. Constructing effective questionnaires. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2000. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483349022.

Cole ZD, Donohoe HM, Stellefson ML. Internet-based Delphi research: case based discussion. Environ Manage. 2013;51(3):511–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-012-0005-5.

Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(4):401–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002.

Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, Deyo RA. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2009;373(9662):463–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60172-0.

Tender GC, Davidson C, Shields J, et al. Primary pain generator identification by CT-SPECT in patients with degenerative spinal disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2019;47(6):E18. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.9.FOCUS19608.

Jain A, Jain S, Agarwal A, Gambhir S, Shamshery C, Agarwal A. Evaluation of efficacy of bone scan with SPECT/CT in the management of low back pain: a study supported by differential diagnostic local Anesthetic blocks. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(12):1054–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000212.

Cohen SP, Hurley RW, Christo PJ, Winkley J, Mohiuddin MM, Stojanovic MP. Clinical predictors of success and failure for lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(1):45–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ajp.0000210941.04182.ea.

Cohen SP, Bajwa ZH, Kraemer JJ, et al. Factors predicting success and failure for cervical facet radiofrequency denervation: a multi-center analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32(6):495–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rapm.2007.05.009.

Djurasovic M, Carreon LY, Crawford CH, Zook JD, Bratcher KR, Glassman SD. The influence of preoperative MRI findings on lumbar fusion clinical outcomes. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(8):1616–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-012-2244-9.

Shreibati JB, Baker LC. The relationship between low back magnetic resonance imaging, surgery, and spending: impact of physician self-referral status. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(5):1362–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01265.x.

Cohen SP, Huang JHY, Brummett C. Facet joint pain–advances in patient selection and treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(2):101–16. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2012.198.

Dreyfuss P, Schwarzer AC, Lau P, Bogduk N. Specificity of lumbar medial branch and L5 dorsal ramus blocks. A computed tomography study. Spine. 1997;22(8):895–902. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199704150-00013.

Saito T, Steinke H, Miyaki T, et al. Analysis of the posterior ramus of the lumbar spinal nerve: the structure of the posterior ramus of the spinal nerve. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(1):88–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e318272f40a.

Perolat R, Kastler A, Nicot B, et al. Facet joint syndrome: from diagnosis to interventional management. Insights Imaging. 2018;9(5):773–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13244-018-0638-x.

Auteroche P. Innervation of the zygapophyseal joints of the lumbar spine. Anat Clin. 1983;5(1):17–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01798869.

Abd-Elsayed A, Narel E, Loebertman M. Is a one prognostic block sufficient to proceed with radiofrequency ablation? A single center experience. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2020;24(6):23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-020-00858-8.

Cohen SP, Doshi TL, Constantinescu OC, et al. Effectiveness of lumbar facet joint blocks and predictive value before radiofrequency denervation: the facet treatment study (FACTS), a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(3):517–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000002274.

Derby R, Melnik I, Lee JE, Lee SH. Correlation of lumbar medial branch neurotomy results with diagnostic medial branch block cutoff values to optimize therapeutic outcome. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2012;13(12):1533–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01500.x.

Dreyfuss P, Stout A, Aprill C, Pollei S, Johnson B, Bogduk N. The significance of multifidus atrophy after successful radiofrequency neurotomy for low back pain. PM R. 2009;1(8):719–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.05.014.

Wu PB, Date ES, Kingery WS. The lumbar multifidus muscle in polysegmentally innervated. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;40(8):483–5.

Barbieri M, Bellini M. Radiofrequency neurotomy for the treatment of chronic pain: interference with implantable medical devices. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2014;46(3):162–5. https://doi.org/10.5603/AIT.2014.0029.

Osborne MD. Radiofrequency neurotomy for a patient with deep brain stimulators: proposed safety guidelines. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2009;10(6):1046–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00686.x.

Wahezi SE, Alexeev E, Georgy JS, et al. Lumbar medial branch block volume-dependent dispersion patterns as a predictor for ablation success: a cadaveric study. PM R. 2018;10(6):616–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.11.011.

Tran J, Peng P, Loh E. Anatomical study of the medial branches of the lumbar dorsal rami: implications for image-guided intervention. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2022-103653. (Published online May 19).

Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, Pauza K, Joshi A, McLarty J, Bogduk N. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophysial joint pain. Spine. 2000;25(10):1270–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200005150-00012.

Koh JC, Kim DH, Lee YW, Choi JB, Ha DH, An JW. Relationship between paravertebral muscle twitching and long-term effects of radiofrequency medial branch neurotomy. Korean J Pain. 2017;30(4):296–303. https://doi.org/10.3344/kjp.2017.30.4.296.

Gofeld M, Faclier G. Radiofrequency denervation of the lumbar zygapophysial joints–targeting the best practice. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2008;9(2):204–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00345.x.

Ball RD. The science of conventional and water-cooled monopolar lumbar radiofrequency rhizotomy: an electrical engineering point of view. Pain Physician. 2014;17(2):E175-211.

Provenzano DA. Think before you inject: understanding electrophysiological radiofrequency principles and the importance of the local tissue environment. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2014;39(4):269–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/AAP.0000000000000114.

Leoni MLG, Schatman ME, Demartini L, Lo Bianco G, Terranova G. Genicular nerve pulsed dose radiofrequency (PDRF) compared to intra-articular and genicular nerve PDRF in knee osteoarthritis pain: a propensity score-matched analysis. J Pain Res. 2020;13:1315–21. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S240138.

Giles LG, Taylor JR. Human zygapophyseal joint capsule and synovial fold innervation. Br J Rheumatol. 1987;26(2):93–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/26.2.93.

Zhou L, Schneck CD, Shao Z. The anatomy of dorsal ramus nerves and its implications in lower back pain. Neurosci Med. 2012;3(2):192–201. https://doi.org/10.4236/nm.2012.32025.

Eldabe S, Tariq A, Nath S, et al. Best practice in radiofrequency denervation of the lumbar facet joints: a consensus technique. Br J Pain. 2020;14(1):47–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463719840053.

Smuck M, Crisostomo RA, Demirjian R, Fitch DS, Kennedy DJ, Geisser ME. Morphologic changes in the lumbar spine after lumbar medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy: a quantitative radiological study. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc. 2015;15(6):1415–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2013.06.096.

Bajaj HS, Chapman AW. Dropped head syndrome: report of a rare complication after multilevel bilateral cervical radiofrequency neurotomy. Pain Rep. 2022;7(5): e1037. https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000001037.

Oswald KAC, Ekengele IV, Hoppe IS, Streitberger IK, Harnik IM, Albers ICE. Radiofrequency Neurotomy does not cause fatty degeneration of the lumbar paraspinal musculature in patients with chronic lumbar pain-a retrospective 3D-computer-assisted MRI analysis using iSix software. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnac103. (Published online July 1).

Schakman O, Kalista S, Barbé C, Loumaye A, Thissen JP. Glucocorticoid-induced skeletal muscle atrophy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45(10):2163–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2013.05.036.

Bogduk N. Criteria for determining if a treatment for pain works. Interv Pain Med. 2022;1: 100125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpm.2022.100125.

Barr KP, Griggs M, Cadby T. Lumbar stabilization: a review of core concepts and current literature, part 2. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(1):72–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.phm.0000250566.44629.a0.

Cetin H, Kose N, Turkmen C, Dulger E, Bilgin S, Sahin A. Do stabilization exercises increase the effects of lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation? Turk Neurosurg. 2019;29(4):576–83. https://doi.org/10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.24946-18.2.

Cohen SP, Williams KA, Kurihara C, et al. Multicenter, randomized, comparative cost-effectiveness study comparing 0, 1, and 2 diagnostic medial branch (facet joint nerve) block treatment paradigms before lumbar facet radiofrequency denervation. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(2):395–405. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e33ae5.

Son JH, Kim SD, Kim SH, Lim DJ, Park JY. The efficacy of repeated radiofrequency medial branch neurotomy for lumbar facet syndrome. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2010;48(3):240–3. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2010.48.3.240.

Smuck M, Crisostomo RA, Trivedi K, Agrawal D. Success of initial and repeated medial branch neurotomy for zygapophysial joint pain: a systematic review. PM R. 2012;4(9):686–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.06.007.

D’Souza RS, Langford B, Moeschler S. Gender representation in fellowship program director positions in ACGME-accredited chronic pain and acute pain fellowship programs. Pain Med Malden Mass. 2021;22(6):1360–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnab041.

D’Souza RS, King R, Strand N, Barman R, Olatoye O. Sex disparity persists in pain medicine: a cross-sectional study of chairpersons within ACGME-accredited chronic pain fellowship programs in the United States. J Educ Perioper Med JEPM. 2022;24(1):E680. https://doi.org/10.46374/volxxiv_issue1_dsouza.

Vittori A, Petrucci E, Cascella M, et al. Pursuing the recovery of severe chronic musculoskeletal pain in Italy: clinical and organizational perspectives from a SIAARTI survey. J Pain Res. 2021;14:3401–10. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S328434.

Cascella M, Vittori A, Petrucci E, et al. Strengths and weaknesses of cancer pain management in Italy: findings from a nationwide SIAARTI survey. Healthc Basel Switz. 2022;10(3):441. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030441.

Santaguida P, Dolovich L, Oliver D, et al. Protocol for a Delphi consensus exercise to identify a core set of criteria for selecting health related outcome measures (HROM) to be used in primary health care. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):152. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0831-5.

Wahezi SE, Duarte RA, Yerra S, et al. Telemedicine during COVID-19 and beyond: a practical guide and best practices multidisciplinary approach for the orthopedic and neurologic pain physical examination. Pain Physician. 2020;23(4S):S205–38.

Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(4):1008–15.

Niederberger M, Spranger J. Delphi technique in health sciences: a map. Front Public Health. 2020;8:457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00457.

Acknowledgements

Compain Research Group members are: Amato Francesco, Amorizzo Ezio, Angelini Lucia, Angelini Carlo, Baciarello Marco, Baldi Claudio, Barbieri Massimo, Bellelli Alberto, Bertini Laura, Bonezzi Cesare, Buonanno Pasquale, Calcarella Giuseppe, Cassini Fabrizio, Ciliberto Giuseppe, Demartini Laura, De Negri Pasquale, Enea Pasquale, Erovigni Emanuela, Gazzeri Roberto, Grossi Paolo, Guardamagna Vittorio, Innamorato Massimo, Lippiello Antonietta, Maniglia Paolo, Masala Salvatore, Mercieri Marco, Micheli Fabrizio, Muto Mario, Natoli Silvia, Nocerino Davide, Nosella Paola, Pais Paolo, Papa Alfonso, Pasquariello Lorenzo, Piraccini Emanuele, Petrone Edoardo, Puntillo Filomena, Sbalzer Nicola, Spinelli Alessio, Tinnirello Andrea, Violini Alessia.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The rapid service fee was funded by the authors. No financial benefits were provided to the authors.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

We thank David Michael Abbott for English revision and editing and the Compain Research Group for promoting the discussions about pain management and its appropriate management. We also thank the Paolo Procacci Foundation for the support in the publication process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization was provided by F.O., methodology was decided by M.C., data curation and formal analysis was performed by M.L.G.L., original draft preparation was performed by M.C., and M.L.G.L., writing review and editing was performed by F.O., R.C., M.L.G.L., G.V., E.C, and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Felice Occhigrossia, Roberta Carpenedob, Matteo Luigi Giuseppe Leonic, Giustino Varrassid, Elisabetta Chinèb, and Marco Cascellae have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study. This Delphi survey did not investigate therapies or pathologies relating to the individual patient. It also did not collect sensitive, personal, or clinical data. For all these reasons, according to the Italian current legislation for non-interventional or observational studies (Ministerial Circular N. 6,2 September 2002), it is only necessary to submit a survey for approval by an Ethics Committee if the following criterion was met: All participants agreed to participate in the survey and signed informed consent.

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

The members of the Compain Research Group are listed in "Acknowledgements".

The original online version of this article was revised to include the Compain Research Group members name.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Occhigrossi, F., Carpenedo, R., Leoni, M.L.G. et al. Delphi-Based Expert Consensus Statements for the Management of Percutaneous Radiofrequency Neurotomy in the Treatment of Lumbar Facet Joint Syndrome. Pain Ther 12, 863–877 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00512-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-023-00512-2