Abstract

Introduction

Cluster headaches can occur with considerable clinical variability. The inter- and intra-individual variability could contribute to the fact that the clinical headache phenotype is not captured by too strict diagnostic criteria, and that the diagnosis and the effective therapy are thereby delayed. The aim of the study was to analyze the severity and extent of the clinical symptoms of episodic and chronic cluster headaches with regard to their variability and to compare them with the requirements of the International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition (ICHD-3) diagnostic criteria.

Methods

The study was carried out as a cross-sectional analysis of 825 patients who had been diagnosed with cluster headaches by their physician. Using an online questionnaire, standardized questions on sociodemographic variables, clinical features of the cluster headache according to ICHD-3, and accompanying clinical symptoms were recorded.

Results

The majority of patients with cluster headaches have clinical features that are mapped by the diagnostic criteria of ICHD-3. However, due to the variability of the symptoms, there is a significant proportion of clinical phenotypes that are not captured by the ICHD-3 criteria for cluster headaches. In addition, change in the side of the pain between the cluster episodes, pain location, as well as persisting pain between the attacks is not addressed in the ICHD-3 criteria. In the foreground of the comorbidities are psychological consequences in the form of depression, sleep disorders, and anxiety.

Conclusions

The variability of the phenotype of cluster headaches can preclude some patients from receiving an appropriate diagnosis and effective therapy if the diagnostic criteria applied are too strict. The occurrence of persisting pain between attacks should also be diagnostically evaluated due to its high prevalence and severity as well as psychological strain. When treating patients with cluster headaches, accompanying psychological illnesses should carefully be taken into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Cluster headaches can occur with considerable clinical variability. |

The inter- and intra-individual variability of the phenotype could contribute to the fact that the clinical headache phenotype is not captured by too strict diagnostic criteria, and that the diagnosis and the effective therapy are thereby delayed. |

The aim of the study was to analyze the severity of the clinical symptoms of episodic and chronic cluster headaches with regard to their variability and to compare them with the requirements of the ICHD-3 criteria. |

What was learned from the study? |

The majority of patients with cluster headaches have clinical features that are mapped by the diagnostic criteria of the ICHD-3. |

However, due to the variability of the symptoms, there is a significant proportion of clinical phenotypes that are not captured by the ICHD-3 criteria for cluster headaches. |

In addition, sequential change in the side of the pain, pain location, as well as persistent pain between the attacks is not addressed in the ICHD-3 criteria. |

The variability of the phenotype should be taken into account in the diagnostic criteria in order to allow a fast and targeted diagnosis as well as the initiation of an effective therapy. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14402471.

Introduction

Cluster headaches are among the most severely debilitating forms of headache [2, 12, 13, 35, 37, 38, 53]. The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition (ICHD-3) [21] offers operational criteria for the diagnosis and classification of cluster headaches. Cluster headaches are characterized by severe unilateral pain. The headache classification denotes the localization of the pain as orbital, supraorbital, and/or temporal. The pain lasts 15–180 min if the attack is left untreated. Conjunctival injection and/or lacrimation, nasal congestion and/or rhinorrhea, eyelid edema, forehead or facial sweating, as well as miosis and/or ptosis are listed as autonomous accompanying symptoms that manifest ipsilaterally to the side of the headache. Restlessness or agitation are grouped as accompanying psychomotor symptoms. At least one accompanying symptom from one or both groups is required for diagnosis. The attack is frequency defined as from once every other day to eight times a day by the International Headache Classification. The operationalized diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 1. The ICHD-3 distinguishes two forms, an episodic and a chronic cluster headache form. The episodic form is defined by the fact that at least two cluster periods occur lasting from 7 days to 1 year (when untreated) that are separated by pain-free remission periods of ≥ 3 months. In the chronic form, such a remission phase is absent or shorter than 3 months over the duration of at least 1 year [21].

Despite these explicit and operationally specified criteria, there is a significant delay in cluster headache diagnosis in everyday clinical practice [9, 37, 51]. One reason for this is that cluster headaches are counted towards the rare forms of headaches. The 1-year prevalence is given as about one affected person per 1000 people [42,43,44, 54]. From a clinical standpoint, cluster headaches can also occur with considerable variability [46, 54]. The inter- and intra-individual variability of the phenotype could contribute to the fact that the clinical headache phenotype is not captured by too strict diagnostic criteria. Clinical features that occur in cluster headaches but that are not listed in the International Headache Classification could mean that the diagnosis of cluster headache is not made, and other diagnoses are considered more likely as part of the differential diagnosis [3, 17, 18, 20, 28, 32, 36, 37, 57].

In order to record the variability of the clinical picture of cluster headaches, we asked 825 patients, who had been diagnosed with episodic or chronic cluster headaches by their physician, about the clinical headache phenotype and compared it with the requirements of the ICHD-3 criteria. The aim of the study was to record the type of the clinical symptoms and to analyze their variability.

Methods

Study Design

The study was carried out as a cross-sectional observational cohort analysis of patients who had been diagnosed with cluster headaches by their physician. The survey took place between September and November 2019. An online questionnaire was developed for this purpose. The questionnaire contained standardized questions on sociodemographic variables, clinical features of cluster headache according to ICHD-3, and accompanying clinical symptoms. The patients were informed about the survey via social networks and motivated to participate. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Kiel (D 531/19). All study information and patient consent forms were approved by the ethics committee. The study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its subsequent revisions.

Study Population

A total of 825 patients who had been diagnosed with cluster headaches by their physician took part in the survey (for details on the sociodemographic variables see Table 2). The participants were 482 women (58.4%) and 343 (41.6%) men. The mean age was 44.98 ± 11.89 years. On average, the patients had suffered from cluster headaches for 16.31 ± 11.61 years, and 47.6% had been diagnosed with episodic and 52.4% with chronic cluster headache.

Data Collection

Data on the clinical features and corresponding variables were recorded using a standardized online questionnaire using multiple-choice questions, numerical data, or free text where appropriate. Participants were recruited via social networks of cluster headache self-help groups in cooperation with the German Association of the cluster headache self-help groups and via online social headache communities in Germany. Inclusion criterion was a medically diagnosed cluster headache disorder. Exclusion criteria were headache without a clear diagnosis. The questionnaire consisted of 77 individual questions. Answering the questions took about 20 min. Multiple participation was prevented by blocking the browser session ID and setting a cookie. The diagnosis of a cluster headache made by a physician was recorded using the questionnaire. The answers were collected in an online database. At the beginning of the questionnaire, subjects were informed that data were collected anonymously in compliance with the recommendations of the ethics committee. They were also informed that due to the anonymization, it was not possible to revoke participation in the study after any answers have been sent.

Bias and Missing Data

Patients without Internet access could not take part in this study. The study is unable to analyze cluster headache characteristics from people who did not voluntarily participate. Missing data were not assumed for this descriptive analysis. Complete data were not available for all variables, so the denominators differ between individual analyzes.

Statistics

Nominal variables are shown in absolute or relative (%) frequencies. Continuous variables are presented with the arithmetic mean and standard deviation. The Chi-square test was used to analyze the association between qualitative variables. The t test was used to statistically analyze continuous variables for significant differences. Correlations were calculated as the Pearson correlation coefficient and tested for significance (two-tailed). All statistical information was based on non-missing data. The 5% level of significance (alpha = 0.05) was considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 27.

Results

Figure 1 shows the frequency distribution of pain intensity; 35.1% and 58.1% of patients reported severe or very severe headache intensities, respectively; 6.7% of the patients reported a moderate pain intensity.

The localization of the pain (Fig. 2) was described by 40.5% as unilateral on the left and 45.2% unilateral on the right side. A sequential bilateral pain localization (cluster attacks alternating bilaterally) was reported by 14.3% of the patients.

Pain was most frequently felt in the orbital area by 69.9% of patients; 53.7% localized the pain to the temporal area, 42.3% supraorbital, and 32.8% in the upper jaw area; 27.8% localized it to the forehead, 25.2% to the neck, 21.5% to the back of the head, and 4.6% to other regions (Fig. 3).

As the most frequent typical duration of the pain attacks, untreated or treated unsuccessfully (Fig. 4), 19.2% of the patients stated a time of 30 min; 54.4% report a duration of between 15 to 60 min, 89.8% of the patients stated that the pain attacks lasted between 15 to 180 min; 10.2% of the patients described the duration of the pain attacks between 180 min and longer than 270 min (Fig. 4).

The most common accompanying symptom was lacrimation in 58.7% of patients. Nasal congestion was reported by 54.7%, restlessness by 54.6%, rhinorrhea by 46.4%, sweating by 41.8%, reddening of the eye by 40.4%, ptosis by 35.9%, eyelid edema by 25.5%, and miosis by 13.2% of the surveyed patients (Fig. 5).

Persisting pain in the cluster headache area between cluster headache attacks was reported by 47% of the surveyed patients (Fig. 6). The persisting pain between attacks occurred ipsilateral to the side that is affected by the cluster attacks in 37% of cases. On the contralateral side, only 1% of patients reported persistent pain. Persisting bilateral pain was reported by 9% of the patients.

Patients with chronic cluster headache significantly more frequently had persisting headaches than patients with an episodic headache form (Fig. 7; Chi-square test p = 0.002); 39.5% of the patients with chronic cluster headache reported permanent ipsilateral headache in the cluster area, 12% of these patients reported permanent bilateral headache in the cluster area. In comparison, 34.8% of those affected with episodic cluster headaches showed ipsilateral and 5.5% bilateral persisting headaches in the cluster headache area.

The intensity of the persisting pain between cluster attacks was stated as moderate in 44% of the patients, severe in 24.0%, and very severe in 6.7% (Fig. 8); 23.3% of the patients reported mild headaches. There were no significant differences in pain intensity between episodic and chronic forms.

The most frequently reported attack frequency was two attacks per day, reported by 19% of patients. Around 70% of patients had an attack frequency of between one and four attacks per day. More than eight attacks per day were found in 6.6% of the patients (Fig. 9).

The mean attack frequency was 3.98 ± 3.19 attacks per day. The minimum was one attack, and the maximum was 28 attacks per day. There were no significant differences between men and women with regard to the frequency of attacks (4.05 ± 3.30 versus 3.89 ± 3.04 attacks per day). In contrast, in the group of patients with a chronic form, there were significantly more attacks per day than in the group with an episodic form (4.31 ± 3.48 versus 3.63 ± 2.82 cluster attacks per day; t test: p = 0.005).

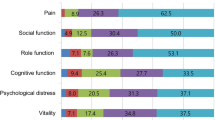

Psychiatric disorders such as depression (19.1%), sleep disorders (16.9%), and anxiety (12.3%) were most often comorbid with cluster headaches. Furthermore, a number of other disorders were found frequently, in particular allergies (16.4%), obesity (12.1%), orthopedic (11.2%), neurological (11.1%), as well as other disorders (Fig. 10).

The cluster attack duration was significantly longer in women than in men (138.14 ± 140.91 versus 103.90 ± 104.89 min; Table 3; p = 0.000). Patients with a chronic form showed significantly longer attack durations than patients with an episodic form (97.90 ± 99.84 versus 147.36 ± 145.23 min; p = 0.000; Table 4). The attack frequency, recorded as the average number of attacks per day, was also significantly higher in the chronic form than in the episodic form (3.63 ± 2.82 versus 4.31 ± 3.41; p = 0.000). Patients with the episodic form showed significantly lower attack intensities than patients with a chronic form (3.60 ± 0.59 versus 3.42 ± 0.64; p = 0.003). The duration of the cluster headache disorder was significantly longer in the chronic form than in the episodic form (15.09 ± 10.77 versus 17.40 ± 12.21 years; p = 0.004). Patients with a chronic form had a significantly later onset of cluster headache than patients with an episodic form (28.94 ± 11.75 versus 29.27 ± 12.44 years; p = 0.038; Table 4).

There were no significant correlations between the duration of the attacks and the attack frequency (Pearson correlation (two-tailed) − 0.027, p = 0.490). In contrast, there were significant positive correlations between the frequency of attacks per day and the age of the patient (Pearson correlation (two-tailed) 0.092, p = 0.016) and the pain intensity of the attacks (Pearson correlation (two-tailed) 0.108, p = 0.005).

Figures 11 and 12 show the frequency distributions of the medications taken for acute therapy and for preventive treatment. At the time of the survey, 67.7% of patients had no active episode.

Discussion

This study is unique in that it evaluated a homogeneous large group of cluster headache patients, well defined by a self-help organization, who regard themselves as cluster headache patients and for whom a diagnosis of a cluster headache was made by their physician. The results confirm that the majority of patients with cluster headaches have clinical features that are mapped by the diagnostic criteria of ICHD-3 [21]. However, due to the variability of the symptoms, there is a significant proportion of clinical phenotypes that are not captured by the ICHD-3 criteria. Severe or very severe pain intensity (criterion B of the ICHD-3) applies to 93.2% of patients. However, 6.8% showed mild or moderate pain; 85.7% of the patients showed unilateral pain, 14.3% showed a sequential change of side meaning that cluster attacks can alternate bilaterally. This phenomenon is not explicitly listed in the diagnostic criteria and can therefore lead to delays and incorrect diagnoses in patients with cluster headaches [1, 9, 46, 53]. The change of side is not specifically referred to in the diagnostic criteria and in the notes of the ICHD-3. The most common pain location was orbital, supraorbital, and/or temporal. However, around a third of patients also experienced pain in the upper jaw, neck, and back of the head. These pain locations have not yet been considered in the ICHD-3 criteria. The duration of the headache was 15–180 min in 89.8% of patients. There were, however, 10.2% of patients with a longer duration of pain. Patients with this attack duration are not included in the current headache classification. The autonomic symptoms lacrimation, nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, sweating, reddening of the eye, ptosis, eyelid edema, and miosis are found in high frequency as accompanying symptoms, particularly lacrimation, nasal congestion and rhinorrhea. Lacrimation was the most common accompanying symptom in 58.7% of our patients. In other current analyses, lacrimation was also found as the most common accompanying symptom in 58.8% [50]. Psychomotor accompanying symptoms such as restlessness and agitation were found in 54.6% of our patients. The data support the special consideration of these psychomotor symptoms in addition to the autonomic symptoms as an independent diagnostic criterion that alone can justify the diagnosis of a cluster headache within the framework of criterion C in the ICHD-3 criteria [21].

Persisting pain between individual cluster attacks has not yet been explicitly mentioned in ICHD-3. These were found in 47% of patients between attacks. Persisting pain occurred ipsilaterally in 37%, bilaterally in 9%, and contralaterally in 1% of patients. They are more common in chronic cluster headache than in episodic cluster headache. They can contribute to a further increase in the level of suffering. Since persisting pain was reported by almost half of those affected, it could lead to other headache and facial pain being considered as a diagnosis delaying the correct diagnosis of cluster headache [9, 14,15,16, 19, 46,47,48, 51]. The intensity of the persisting pain was mild or moderate in 67.3%. However, 24% reported severe and 6.7% even very severe persisting pain. If the persisting pain in the interval between attacks is severe or very severe, it can delay and make a correct diagnosis more difficult [10, 11, 30, 31, 56]. Persisting pain may not respond to the prophylactic treatment effective for cluster headache attacks and requires further therapeutic considerations [9, 33, 45, 46, 48]. Little attention has been paid to this situation so far, and further studies are required.

Regarding the attack frequency, it was found that 6.6% of the patients had more than eight attacks per day. The most common attack frequency was between one and four attacks per day. If more than eight attacks occur per day, criterion D of the ICHD-3 criteria for cluster headache is not fulfilled [21] and the diagnosis cannot be made. When using the classification for making a diagnosis, it should therefore also be taken into account that some of the patients can experience more than eight attacks per day. With chronic cluster headache, significantly more and longer attacks occur than with episodic cluster headache. This fact, besides chronicity itself, is another cause of increased suffering in patients with chronic cluster headache [34, 45, 47].

The most frequent comorbidities shown by this study were psychiatric disorders in the form of depression, sleep disorders, and anxiety. Comorbidities were recorded as they were known to the patients based on their medical diagnosis and treatment initiated by their physician(s). These comorbidities can significantly increase the level of suffering. Psychiatric disorders should receive careful attention in the care of patients with cluster headaches [7, 22,23,24,25, 39, 40, 47].

The analysis shows that the participants in the study received treatment for acute therapy and prevention of cluster headaches largely in line with existing guidelines. This positive finding may be related to the involvement of the patient in specialized self-help groups for cluster headaches with extensive exchange about therapeutic options. In addition to acute and prophylactic pharmacological treatment of cluster headaches, the focus should also be on providing education, psychotherapeutic intervention and the involvement of relatives.

The age at the onset of the cluster headache disorder differed between men and women (28.69 ± 12.3 versus 29.67 ± 11.73 years). Cluster headache occurs later in life than migraine. On the other hand, women suffer significantly longer cluster headache attacks than men, so that there are significant gender differences analogous to other studies [26, 27, 29, 41, 52]. The intensity of the attacks is also reported to be higher in women than in men. These data indicate an increased level of suffering in women with cluster headaches. Perhaps this is one reason why the proportion of women in our study was relatively high. The high proportion of female participants could also be related to a higher affinity of women to social networks [49]. Overlap with other headache disorders such as migraine or medication-overuse headache is also possible. However, since these headache phenotypes differ markedly, a potential confound is unlikely. The ICHD-3 specifies a male: female gender ratio of 3:1. This is not reflected in the participating population. The study was not designed to analyze prevalence in an epidemiological sense. The aim was to record the headache phenotype in an existing cohort of patients who were diagnosed as cluster headaches in the healthcare setting and who are organized in cluster headache self-help groups.

In the chronic form, the duration and frequency of the attack were significantly higher than in the episodic form. It is therefore important to formulate the correct diagnosis quickly in order to initiate an effective therapy, especially in the chronic form. The frequency of attacks was positively correlated with the age of the patient and the intensity of the pain. This also emphasizes the importance of making a correct diagnosis as well as initiating therapy in a timely manner.

The difficulties in diagnosing cluster headaches are manifold. They include the relative rarity of the disorder compared to other forms of headache, the episodic course and the neglected training in the diagnosis and treatment of headaches [4, 6, 9, 51, 53, 55]. The variable clinical picture, as the results of this study show, is a further contributing factor. The very strict explicit criteria of ICHD-3 may exclude some of the patients from the diagnosis. For the pain criteria (criterion B), this applies to pain intensity, pain localization, and pain duration. In particular, the sequential change of side between active periods should be taken into account in the diagnosis and should not be an argument against the diagnosis of a cluster headache. The accompanying symptoms of criterion C of the ICHD-3 comprehensively describe the most important diagnostic criteria. This also applies to restlessness and agitation, which have been given a separate number under the accompanying criteria and are highly relevant for the differentiation from migraine forms. The occurrence of persisting pain between cluster attacks should also be enquired about with regard to their high prevalence and intensity as well as the effect on the level of suffering in cluster headache patients [5, 8, 12]. When devising the therapeutic plan, it should be checked whether such persisting pain also requires a specific treatment; the therapy should not focus solely on the cluster headache attacks [51]. Criterion D covers the frequency of attacks per day. It turns out that 6.6% of the patients have more than eight attacks per day. If this situation is not taken into account, misdiagnoses may result. In the foreground of comorbidities in cluster headache are psychiatric disorders such as depression, sleep disorders, and anxiety. When treating patients with cluster headaches, these comorbidities should also be taken into account carefully. They should not result in cluster headache being regarded as a psychosomatic illness in the event of diagnostic uncertainty [23].

This study has several limitations. By voluntarily participating in the study, it is possible that participants with particularly pronounced headaches preferentially participated. The resulting clinical headache phenotype could thus represent particularly severe forms. We have tried to capture the headache phenotype in the most precise way possible by recruiting a large number of participants. The analysis could not capture the diagnostic criteria according to which the patients' headaches were classified and diagnosed by their physicians. The diagnosis could have been made by the physician using to the ICHD-3 criteria, but this could not be verified as part of the study. The patients were active in cluster headache self-help groups. It can therefore be assumed that their headache picture corresponded to the ICHD-3 criteria for cluster headaches, including probable cluster headache or a broader cluster headache-like disorder, which led to the diagnosis of cluster headache. The basis of the survey was the headache phenotype, which is treated as cluster headache in the real-world healthcare setting. It is possible that some of the cluster headaches explicitly met the ICHD-3 criteria over certain periods of time. Others might not meet the ICHD-3 criteria due to the inter- and intra-individual variability. In particular, the possible intra-individual variability should be examined in further studies. The analyses are based on the answers given in the questionnaire. False-positive medical diagnoses cannot therefore be ruled out. However, this seems unlikely, as the patients were actively participating in cluster headache support groups with extensive experience with the condition. A large proportion of the patients reported the phenotype from memory; at the time of the survey, 67.7% had no active cluster episode. A recall bias can therefore also be assumed. In view of the very long course of the disorder, however, the influence of such a bias can be assumed to be minor.

Conclusions

This analysis provides evidence that the majority of patients with cluster headaches have clinical features that are mapped by the diagnostic criteria of the ICHD-3. However, due to the variability of the symptoms, there is a significant proportion of clinical phenotypes that are not captured by the ICHD-3 criteria for cluster headaches. In addition, sequential change in the side of the pain, pain location, as well as persistent pain between the attacks should be considered in the diagnosis and classification of cluster headaches. The variability of the phenotype should be taken into account in order to allow a fast and targeted diagnosis as well as the initiation of an effective therapy.

References

Bahra A, Goadsby PJ. Diagnostic delays and mis-management in cluster headache. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;109:175–9.

Barloese MCJ, Beske RP, Petersen AS, et al. Episodic and Chronic cluster headache: differences in family history, traumatic head injury, and chronorisk. Headache. 2020;60:515–25.

Burish M. Cluster headache and other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2018;24:1137–56.

Buture A, Ahmed F, Dikomitis L, et al. Systematic literature review on the delays in the diagnosis and misdiagnosis of cluster headache. Neurol Sci. 2019;40:25–39.

Choong CK, Ford JH, Nyhuis AW, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment patterns among patients diagnosed with cluster headache in U.S. Healthc Claims Data Headache. 2017;57:1359–74.

Chung PW, Cho SJ, Kim BK, et al. Development and validation of the cluster headache screening questionnaire. J Clin Neurol. 2019;15:90–6.

Donnet A, Lanteri-Minet M, Guegan-Massardier E, et al. Chronic cluster headache: a French clinical descriptive study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1354–8.

Ford JH, Nero D, Kim G, et al. Societal burden of cluster headache in the United States: a descriptive economic analysis. J Med Econ. 2018;21:107–11.

Frederiksen HH, Lund NL, Barloese MC, et al. Diagnostic delay of cluster headache: a cohort study from the Danish Cluster Headache Survey. Cephalalgia. 2020;40:49–56.

Gaul C, Christmann N, Schroder D, et al. Differences in clinical characteristics and frequency of accompanying migraine features in episodic and chronic cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:571–7.

Gil-Martinez A, Navarro-Fernandez G, Mangas-Guijarro MA, et al. Hyperalgesia and central sensitization signs in patients with cluster headache: a cross-sectional study. Pain Med. 2019;20:2562–70.

Goadsby PJ, Cittadini E, Burns B, et al. Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias: diagnostic and therapeutic developments. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21:323–30.

Goadsby PJ, Cittadini E, Cohen AS. Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias: paroxysmal hemicrania, SUNCT/SUNA, and hemicrania continua. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:186–91.

Göbel A, Göbel CH, Göbel H. Phenotype of migraine headache and migraine aura of Richard Wagner. Cephalalgia. 2014;34:1004–11.

Göbel CH, Karstedt SC, Münte TF, Göbel H, Wolfrum S, Lebedeva ER, Olesen J, Royl G. Explicit diagnostic criteria for transient ischemic attacks used in the emergency department are highly sensitive and specific. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;50(1):62–7. https://doi.org/10.1159/000512182.

Göbel CH, Karstedt SC, Münte TF, et al. ICHD-3 is significantly more specific than ICHD-3 beta for diagnosis of migraine with aura and with typical aura. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:2.

Göbel H. Classification of headaches. Cephalalgia. 2001;21:770–3.

Göbel H, Heinze-Kuhn K, Petersen I, et al. Classification and therapy of medication-overuse headache: impact of the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders. Schmerz. 2014;28:191–204.

Göbel H, Heinze A, Heinze-Kuhn K, et al. Modern migraine therapy-interdisciplinary long-term care. Internist (Berl). 2020;61:326–32.

Headache Classification C, Olesen J, Bousser MG, et al. New appendix criteria open for a broader concept of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:742–6.

Headache Classification Committee. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1–211.

Joshi S, Rizzoli P, Loder E. The comorbidity burden of patients with cluster headache: a population-based study. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:76.

Kim BS, Chung PW, Kim BK, et al. The impact of remission and coexisting migraine on anxiety and depression in cluster headache. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:58.

Liang JF, Chen YT, Fuh JL, et al. Cluster headache is associated with an increased risk of depression: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:182–9.

Louter MA, Wilbrink LA, Haan J, et al. Cluster headache and depression. Neurology. 2016;87:1899–906.

Lund N, Barloese M, Petersen A, et al. Chronobiology differs between men and women with cluster headache, clinical phenotype does not. Neurology. 2017;88:1069–76.

Lund NLT, Snoer AH, Jensen RH. The influence of lifestyle and gender on cluster headache. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32:443–8.

Mainardi F, Trucco M, Maggioni F, et al. Cluster-like headache. A comprehensive reappraisal. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:399–412.

Manzoni GC, Camarda C, Genovese A, et al. Cluster headache in relation to different age groups. Neurol Sci. 2019;40:9–13.

Marmura MJ, Abbas M, Ashkenazi A. Dynamic mechanical (brush) allodynia in cluster headache: a prevalence study in a tertiary headache clinic. J Headache Pain. 2009;10:255–8.

Marmura MJ, Pello SJ, Young WB. Interictal pain in cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:1531–4.

Matharu MS, Goadsby PJ. Cluster headache: focus on emerging therapies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004;4:895–907.

Moon HS, Cho SJ, Kim BK, et al. Field testing the diagnostic criteria of cluster headache in the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders: a cross-sectional multicentre study. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:900–7.

Negro A, Sciattella P, Spuntarelli V, et al. Direct and indirect costs of cluster headache: a prospective analysis in a tertiary level headache centre. J Headache Pain. 2020;21:44.

Olesen J. International Classification of Headache Disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:396–7.

Olesen J, Steiner T, Bousser MG, et al. Proposals for new standardized general diagnostic criteria for the secondary headaches. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:1331–6.

Pergolizzi JV Jr, Magnusson P, Lequang JA, et al. Exploring the connection between sleep and cluster headache: a narrative review. Pain Ther. 2020;9:359–71.

Ravishankar K. Classification of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgia: what has changed in International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 beta? Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2018;21:S45–50.

Robbins MS. The psychiatric comorbidities of cluster headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17:313.

Robbins MS, Bronheim R, Lipton RB, et al. Depression and anxiety in episodic and chronic cluster headache: a pilot study. Headache. 2012;52:600–11.

Rozen TD, Fishman RS. Female cluster headache in the United States of America: what are the gender differences? Results from the United States Cluster Headache Survey. J Neurol Sci. 2012;317:17–28.

Russell MB. Epidemiology and genetics of cluster headache. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:279–83.

Russell MB. Genetic epidemiology of migraine and cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 1997;17:683–701.

Sjaastad O, Bakketeig LS. Cluster headache prevalence. Vaga study of headache epidemiology. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:528–33.

Sjostrand C, Alexanderson K, Josefsson P, et al. Sickness absence and disability pension days in patients with cluster headache and matched references. Neurology. 2020;94:e2213–21.

Snoer AH, Lund N, Jensen RH, et al. More precise phenotyping of cluster headache using prospective attack reports. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:1303-e1385.

Sohn JH, Park JW, Lee MJ, et al. Clinical factors influencing the impact of cluster headache from a prospective multicenter study. Sci Rep. 2020;10:2428.

Steinberg A, Josefsson P, Alexanderson K, et al. Cluster headache: Prevalence, sickness absence, and disability pension in working ages in Sweden. Neurology. 2019;93:e404–13.

Tufekci Z. Grooming, gossip, facebook and myspace. Inf Commun Soc. 2008;11:544–64.

Uluduz D, Ayta S, Ozge A, et al. Cranial autonomic features in migraine and migrainous features in cluster headache. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2018;55:220–4.

Van Vliet JA, Eekers PJ, Haan J, et al. Features involved in the diagnostic delay of cluster headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1123–5.

Viganò A, Savastano E, Petolicchio B, et al. A study of clinical features and risk factors of self-referring emergency department headache patients: a comparison with headache center outpatients. Eur Neurol. 2020;83:34–40.

Vikelis M, Rapoport AM. Cluster headache in Greece: an observational clinical and demographic study of 302 patients. J Headache Pain. 2016;17:88.

Wei DY, Yuan Ong JJ, Goadsby PJ. Cluster headache: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2018;21:S3–8.

Wheeler SD, Carrazana EJ. Delayed diagnosis of cluster headache in African-American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2001;93:31–6.

Wilbrink LA, Louter MA, Teernstra OPM, et al. Allodynia in cluster headache. Pain. 2017;158:1113–7.

Zidverc-Trajkovic J, Podgorac A, Radojicic A, et al. Migraine-like accompanying features in patients with cluster headache. How important are they? Headache. 2013;53:1464–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Dr. Carl Göbel – design and conceptualization of the study, interpretation of the results, contributed to statistical analysis, writing of the first draft of the manuscript.

Dr. Axel Heinze – contribution to interpretation and analysis.

Sarah Karstedt - contribution to interpretation and analysis.

Britta Koch – contribution to interpretation and analysis.

Prof. Dr. Hartmut Göbel – design and conceptualization of the study, co-writing of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Carl H. Göbel, Sarah Karstedt, Axel Heinze, Britta Koch, and Hartmut Göbel declare no financial conflicts and no competing interests.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The ethics committee of the medical faculty of the Christian-Albrechts University Kiel approved the study (D 531/19). All subjects gave their informed consent prior to participation. The study was performed in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Göbel, C.H., Karstedt, S., Heinze, A. et al. Phenotype of Cluster Headache: Clinical Variability, Persisting Pain Between Attacks, and Comorbidities—An Observational Cohort Study in 825 Patients. Pain Ther 10, 1121–1137 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-021-00267-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-021-00267-8