Abstract

North America and select other Commonwealth jurisdictions have been experiencing unprecedented opioid epidemics characterized by excessive and persistently high levels of opioid misuse, morbidity and mortality, and related disease burden. Recent discussions have considered whether New Zealand might undergo or needs to expect a similar ‘opioid crisis’. Towards further informing these considerations, we examine and compare essential, publicly available indicators of opioid utilization and harms (mortality) from New Zealand and the Canadian province of Ontario, due to the fact that both operate public health care systems in similar socio-cultural settings. We find that the two jurisdictions have featured vastly different population levels of opioid exposure, opioid consumption patterns (e.g., high-dose/long-term/high-risk prescribing) known as key predictors of adverse outcomes, and levels of opioid mortality as evidenced by concrete epidemiological indicators and data. Specifically for opioid-related death rates, these were already approximately threefold higher in Ontario compared to New Zealand based on most recent comparison data (e.g., 2012); these differentials have likely further grown more recently given major and distinct changes in population-level opioid exposure and risks, and subsequent opioid-related deaths since then in Ontario. Based on the present data and related evidence, New Zealand does not seem to need to anticipate an opioid mortality epidemic similar to that experienced in North America; however, it would be of interest to establish more comprehensive and timely surveillance of key system-level indicators of opioid use and harms as are standard in North America. As such, this inter-jurisdictional comparison makes for a case study in starkly contrasting scenarios of opioid use and harms, the drivers behind which deserve further systematic examination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Canada, and other wealthy Commonwealth countries, have been experiencing severe opioid-related health crises (‘epidemic’) including high levels of mortality. |

We compare key available population-level indicators of opioid use and harm for New Zealand and Canada (Ontario). |

The two jurisdictions feature vast differences in population levels and trajectories of opioid exposure, risk patterns (e.g., high-dose/long-duration) of opioid utilization and opioid mortality. |

Ontario’s opioid mortality rate was already approximately threefold that of New Zealand before major changes in opioid exposure and fatalities; New Zealand is unlikely to experience an opioid crisis similar to North America. |

We present an instructive comparison study of opioid-related harm and policy indicators within socio-culturally similar systems. |

Digital features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13348127.

North America has been experiencing an unprecedented, severe public health crisis, or ‘epidemic’, related to opioid misuse and health harms for over a decade now; this crisis has been characterized in particular by excessively and persistently high levels of opioid-related fatalities and related disease burden [1,2,3]. In Canada, following persistent increases for over a decade, there were a record of 4398 opioid-related deaths in 2018; which, when translated into a population rate, has been similar to the mortality rate experienced in the United States ([US], 47,000 deaths) [4, 5]. In both countries, opioid-related mortality has been shown to slow gains in life expectancy in the general population [6,7,8,9]. Similar, while not as extreme, increases in opioid-related harms, including mortality, have been reported for other wealthy Commonwealth jurisdictions (e.g., the United Kingdom [UK], Australia) [10, 11]. On the basis of these experiences, recent discussions have considered whether New Zealand might undergo or need to expect a similar ‘opioid crisis’ [12, 13]. Towards further informing these considerations, we will briefly present and compare key, publicly available indicators on opioid use and mortality from New Zealand and Canada, with a main focus on Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, home to comprehensive population-level data on opioid utilization and related outcomes (e.g., morbidity, mortality). Canada, more so than the US, may serve as a meaningful comparator for New Zealand, given its single-payer public health care system and other socio-cultural similarities, combined with the availability of related population-based administrative health care and utilization data [14, 15].

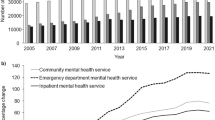

Relevant opioid-related data for New Zealand, unfortunately, are quite limited. New Zealand’s reported annual population levels of opioid consumption—based on International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) data in Defined Daily Doses [DDD]/day/1,000,000—gradually increased from 4930 DDD/1,000,000/day (2000-2002) to 10,164 DDD/1,000,000/day (2009-2011) to 12,469 DDD/1,000,000/day (2016-2018). Through the entire period, however, New Zealand’s opioid consumption levels were below those of North America, the UK, and Australia [16,17,18,19]. Over the past decade, about half of New Zealand’s reported opioid consumption was for methadone (mostly used for pharmacotherapeutic opioid-dependence treatment), with the analgesic products morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl further commonly used. The ‘Atlas on Health Care Variation’ provides some basic details on opioid utilization parameters and practices in New Zealand [20]. Between 2011 and 2017, the number (rate per 1000 population) of persons in the New Zealand general population receiving a weak opioid (codeine, tramadol) increased from 228,618 (83.6/1000) to 308,936 (101.4/1000); the corresponding number (rate) of those receiving a ‘strong opioid’ increased from 28,613 (14.4/1000) to 34,910 (16.6/1000). Of the total of strong opioids, formulation-specific prescriptions of oxycodone decreased from 15,534 persons in 2011 to 11,350 persons in 2017; conversely, the values for morphine increased from 13,750 (2011) to 23,973 (2017); and fentanyl from 1282 (2011) to 3802 (2017). For strong opioid prescriptions, a longer duration of 6 weeks or more was prescribed to a small proportion, specifically to 12.4% of all opioid prescription recipients in 2011 and 10.3% in 2017; the corresponding formulation-specific long-duration prescription rates were: morphine (12.5/10.3%), oxycodone (12.0/9.9%), and fentanyl (32.6/21.9%). Over time, the proportion of recipients of strong opioids aged 65 years or older, and those prescribed in the context of a public hospital event [from 14,434 (50.4%) in 2011 to 18,331 (52.5%) in 2017] remained steady at about half the case total.

Limited data only are available on opioid-related mortality in New Zealand. Deaths by external causes, including substances-related deaths, are examined by coroners in New Zealand, albeit reported only with substantial (multi-year) delay [12]. For most recent data, Shipton and colleagues (2017) reported the total number (and corresponding rates per 1,000,000 population) of annual opioid-related deaths to have slightly increased from 62 (14.56/1,000,000 (95% CI 11.16,18.66) in 2008 to 71 (16.11/1,000,000 (12.58, 20.31) in 2012; methadone (99), morphine (89), codeine (71), and oxycodone (26) were listed as the main cumulatively contributing formulations for the period [21]. Applying a slightly different methodology but presenting proportionally similar results, Fountain and colleagues (2019) reported annual opioid-related poisoning fatalities by formulation (methadone: 112; morphine: 81; codeine: 46 and oxycodone: 22) for the period 2008–2013 [22].

In contrast, Canada has long featured the globally second-highest levels of opioid consumption, more than tripling from 8713 DDD/1,000,000/day in 2000–2002 to 30,540 DDD/1,000,000/day in 2012-14 yet then—following a series of system-level measures and interventions (e.g., select opioid formulation delisting, implementation of prescription monitoring, revised prescription guidelines/standards) implemented to restrict rising opioid consumption and related harms—declining to 22402 DDD/1,000,000/day by 2016–2018 [16, 23]. This overall inflecting opioid consumption pattern for this period is mirrored for Ontario for the dispensing of specifically strong opioids (10.1 DDD/1000/day in 2005; 14.2 DDD/1000/day in 2011; 7.6 DDD/1000/day in 2018) with weak opioids (13.7 DDD/1000/day in 2005; 12.1 DDD/1000/day in 2011; 7.8 DDD/1000 /day in 2018) following a generally linear declining trend [24]. Strong opioid dispensing in Ontario has predominantly involved oxycodone, hydromorphone, and fentanyl products, i.e., high-potency opioid products, many of which are mainly used in extended-release formulations [25,26,27].

Select details on opioid prescription patterns and characteristics in the Ontario general population are available from administrative data-based systems and their analyses [28, 29]. Specifically, in 2015/2016 (fiscal year), 13.8 million people (or 14% of the general population) received a total of 9,152,247 opioid prescription in Ontario, translating to a population rate of 664/1000 opioid prescriptions [28]. Three-quarters (73%) of the prescriptions were for recipients ages < 65 years, with the large majority community-dispensed. In related analyses for 2016, a total of 1,663,181 individuals (12% of Ontarians) were reported to have been dispensed a prescription opioid to treat pain alone [29]. Among those receiving an immediate-release opioid (98%), half (52%) received a codeine (weak opioid) formulation; among those receiving a long-acting opioid (11%), most also received an immediate-release opioid, yet only 5% received a codeine (weak opioid) formulation. Notably, 37% of those receiving an opioid prescription were ‘ongoing’ users, i.e., persons who received multiple opioid prescription in 2016. Specifically, some 6,885,264 opioid prescriptions were dispensed for 613,270 ongoing users (i.e., an average of > 10 opioid prescriptions per person/year) in 2016. Furthermore, 2,256,158 (33%) of those prescriptions to ‘ongoing’ recipients were for ‘long-acting’ opioid formulations. Moreover, almost half (899,211/40%) of the long-acting opioid, and 5% of the immediate-release (233,863) opioid prescriptions were issued at a daily dose of > 90 mg of morphine or equivalent (MEQ)—a dose level currently considered ‘inappropriate’ prescribing due to high risk for adverse outcomes (e.g., dependence, overdose, injury) as well as in non-compliance with recent opioid prescribing standards [30,31,32]. This complements findings from previous analyses, where high and increasing levels (up to 40%) of high-dose opioid prescribing, then defined at 200 mg MEQ, and associations with hospitalization, had been documented for public drug beneficiaries in Ontario [33, 34].

For mortality, the numbers (population rates) of annual opioid-related fatalities has climbed persistently overtime in Ontario, initially from 571 (43.47/1,000,000) opioid-related deaths in 2010 to 585 (43.31) in 2012 to 728 (53.11/1,000,000) in 2015, and further steeply to 1473 (102.88/1,000,000) in 2018 [14, 35]. Initially in the observation period, the total of opioid-related deaths was predominantly attributed to contributions (~ 90%) from the various leading prescribed strong opioids (i.e., oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, methadone, morphine). This opioid mortality profile gradually changed when, starting around 2015 fentanyl formulations—and increasingly illicit/non-prescription fentanyl and other synthetic/fentanyl analogue products—began to emerge as the principal contributors to opioid fatalities in Ontario (rising to 69% of total opioid-related deaths in 2018) [36, 37].

In the above, we presented and compared select population-level indicators of opioid use and related harms (mortality) for New Zealand and Ontario (Canada). While the data, by natural availability constraints, are crude and limited, they present a useful and instructive ‘big picture’ comparison of two fundamentally different scenarios of opioid-related population exposure and outcome indicators in two wealthy Commonwealth jurisdictions. Both of those entities feature foundations of their medical system extending back to the same roots (originally the UK). The main comparative insights are as follows, beginning with indicators of opioid exposure. First, based on DDD-based measures, Ontario, compared to New Zealand, consistently dispensed twice to three times the total amounts of opioids (depending on year) into the general population over the observation period spanning across two decades; these disproportionalities are even greater when excluding methadone (mostly used for addiction treatment [38]). Several studies have documented strong correlations arising from population levels of opioid dispensing as systemic determinants of adverse (e.g., mortality, morbidity) outcomes [39,40,41]. Second, while the total rates of the subpopulations receiving an opioid prescription may be considered ‘similar’ in the New Zealand (12% in 2017) and Ontario (14% in 2016) general populations, the vast majority (> 80%) of recipients in New Zealand have been prescribed weak opioids (codeine); whereas the majority of prescriptions dispensed involve ‘strong opioids’ (and a large sub-proportion long-acting/slow-release) opioids in Ontario—i.e., opioid formulations featuring markedly higher potency and/or risk profiles for key severe adverse outcomes, including fatalities from acute poisonings [42, 43]. Moreover, while only a small sub-group (approximately 10%) of strong opioid recipients receive them for longer duration in New Zealand, almost 40% of opioid prescription recipients in Ontario are considered ‘recurring’ (long-term) users, with each receiving an average of ten opioid prescriptions/year; in addition, almost one-in-five of those prescriptions (mostly for long-acting formulations) are exceeding ‘high-dose’ thresholds. Both factors are documented as crucial predictors of adverse outcomes [44,45,46,47]. For comparative illustration: the total population rate (1.1%) of long-term recurring users receiving a long-acting opioid in Ontario in 2016—to be considered an ultra-high-risk group for adverse outcomes—is just somewhat smaller than the rate of all persons receiving a strong opioid (1.66%) in New Zealand in 2017 (even before consideration of age or dispensing setting).

Considering fatalities, annual opioid mortality rates in Ontario were already about threefold higher than those of New Zealand (e.g., in 2012 for concrete numeric comparison) before experiencing major further changes in quantity and qualitative characteristics of population-level opioid exposure and subsequent steep increases in opioid-related deaths. While more recent, concrete data on opioid-related deaths for New Zealand are currently not available, it is reasonable to assume that the magnitude of differentials in opioid death rates between the two jurisdictions has further substantially expanded since then and they have been experiencing opioid death rates at even greater, vastly different scales. The vast majority of opioid-related deaths in Ontario, initially, were associated with potent, long-acting opioid formulations (e.g., oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl). These system-level opioid fatality profiles, overall, reflect both levels and over-time changes in opioid dispensing (such correlations previously have been demonstrated specifically for Ontario [39, 48]). Notably, beyond the pre-existing inter-jurisdictional differences in scale, the more recent, marked increases in opioid mortality in Ontario arose following the inflection from substantial growth to sudden decreases in opioid dispensing (beginning around 2013/14) following multiple system-level intervention measures [23, 49, 50]. Subsequent to these reductions, Ontario (similar to other Canadian provinces) experienced sharp increases and growing proportions of opioid-related fatalities mainly involving illicit/toxic opioid (mostly fentanyl) products [36, 51]. Commentators have interpreted these dynamics as a sort of ‘opioid supply shock’ in the face of persistent, high-level demand especially for non-medical opioid use, facilitating a consequential influx of illicit opioid products and consequential increases in related deaths [52, 53]. By all accounts and available indicators, such volatile supply dynamics have not been occurring, nor are realistically on the horizon, in New Zealand.

Considering the available basic data and indicator comparisons, New Zealand and Ontario feature quantitatively and qualitatively starkly different opioid use and harm profiles. While this assessment and related forecasting involves some informed and plausible speculation in the absence of empirical proof only the future can provide, in this context, New Zealand should find itself reasonably protected against a North American-type ‘opioid mortality crisis’ for multiple key factors: First, its population-level opioid exposure has been substantially lower; second, the occurrence of ‘high-risk’ opioid consumption (e.g., involving long-acting/long-duration and/or high-dose opioid use) is vastly more rare; third, its opioid dispensing rates have been far more steady, without the major inflections or oscillations that appear to have facilitated major increases in illicit opioid toxicity supply and harms in Canada. In addition, the differences in main target populations (i.e., older age recipients) and settings (i.e., more hospitals) for opioid dispensing likely add further protection from population-level risks (e.g., diversion, non-medical use, overdose) for possible harm outcomes. While most recent opioid mortality data for New Zealand date back to several years ago, it appears unlikely, based on our examination and related key evidence, that dramatic changes would plausibly be expected in the near future. Nonetheless, it would be in New Zealand’s interest to establish more comprehensive and timely surveillance of key system-level indicators of opioid use and harms (e.g., focusing on opioid dispensing, morbidity/hospitalization and mortality) for monitoring and ‘early warning’ purposes as have become standard in North America [4, 35, 54, 55].

Evidently, tangible factors have maintained or restricted opioid utilization and related harms at paradigmatically more moderate levels in New Zealand, compared to Ontario (Canada). Even in comparison with its neighbor jurisdiction, Australia, New Zealand fares more moderately and better in these respects [10, 56,57,58]. On this basis, the present inter-jurisdictional comparison of opioid-related indicators lays out a compelling case study of two contrasting scenarios of population-level opioid utilization parameters and consequential adverse outcomes, both rooted in Commonwealth and public health system settings. In line with other previous comparison efforts in this realm, the concrete drivers or determinants (e.g., opioid policy/regulation tools, interventions, medical culture) for the marked differences observed should be further systematically examined and better understood [59, 60].

References

Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. The burden of opioid-related mortality in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(2):e180217-e.

Saloner B, McGinty EE, Beletsky L, Bluthenthal R, Beyrer C, Botticelli M, et al. (2018) A public health strategy for the opioid crisis. Public Health Rep. 133(1_suppl):24S-34S.

Fischer B, Pang M, Tyndall M. The opioid death crisis in Canada: crucial lessons for public health. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(2):e81–2.

Vojtila L, Pang M, Goldman B, Kurdyak P, Fischer B. Non-medical opioid use, harms, and interventions in Canada—a 10-year update on an unprecedented substance use-related public health crisis. Drugs Educ Prev Policy. 2020;27(2):118–22.

Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith HI, Davis N. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2017–2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:290–7.

Orpana HM, Lang JJ, George D, Halverson J. At-a-glance—the impact of poisoning-related mortality on life expectancy at birth in Canada, 2000 to 2016. Public Health Agency Can. 2019;39(2):56–60.

Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959–2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996–2016.

Ye X, Sutherland J, Henry B, Tyndall M, Kendall PRW. At-a-glance—impact of drug overdose-related deaths on life expectancy at birth in British Columbia. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can Res Policy Pract. 2018;38(6):248–51.

Dowell D, Arias E, Kochanek K, Anderson R, Guy GP Jr, Losby JL, et al. Contribution of opioid-involved poisoning to the change in life expectancy in the United States, 2000–2015. JAMA. 2017;318(11):1065–7.

Larance B, Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Gisev N, Mattick R, Colledge S, et al. Pharmaceutical opioid use and harm in Australia: the need for proactive and preventative responses. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37(S1):S203–5.

EMCDDA. Drug-related deaths and mortality in Europe: Update from the EMCDDA expert network. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2019.

Morrow PL. The American opioid death epidemic—lessons for New Zealand? N Z Med J. 2018;131(1469):59–63.

Shipton EA. The opioid epidemic—a fast developing public health crisis in the first world. N Z Med J. 2018;131(1469):7–9.

Gomes T, Greaves S, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Measuring the burden of opioid-related mortality in Ontario. Can J Addict Med. 2018;12(5):418–9.

Braithwaite J, Hibbert P, Blakely B, Plumb J, Hannaford N, Long JC, et al. Health system frameworks and performance indicators in eight countries: a comparative international analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2017;5:2050312116686516.

INCB. Narcotic drugs—technical report Austria: United Nations Publication; 2020. Available from: https://www.incb.org/incb/en/narcotic-drugs/Technical_Reports/narcotic_drugs_reports.html. Accessed 30 Aug 2020

INCB. Narcotic drugs: estimated world requirements for 2020—statistics for 2018. New York: United Nations Publication; 2020. p. 2019.

INCB. Narcotic drugs: estimated world requirements for 2013—statistics for 2011. New York: United Nations Publication; 2013. p. 2013.

INCB. Narcotic drugs: estimated world requirements for 2004—statistics for 2002. New York: United Nations Publication; 2004. p. 2003.

Health Quality and Safety Commission. Atlas of healthcare variation: Opioids 2019. Available from: https://public.tableau.com/profile/hqi2803#!/vizhome/Opioidssinglemap/AtlasofHealthcareVariationOpioids. Accessed 30 Aug 2020

Shipton EE, Shipton AJ, Williman JA, Shipton EA. Deaths from opioid overdosing: Implications of coroners’ inquest reports 2008–2012 and annual rise in opioid prescription rates: a population-based cohort study. Pain Ther. 2017;6(2):203–15.

Fountain JS, Reith DM, Tomlin AM, Smith AJ, Tilyard MW. Deaths by poisoning in New Zealand, 2008–2013. Clin Toxicol. 2019;57(11):1087–94.

Fischer B, Rehm J, Tyndall M. Effective Canadian policy to reduce harms from prescription opioids: learning from past failures. Can Med Assoc J. 2016;188(17–18):1240–4.

Fischer B, Jones W, Vojtila L, Kurdyak P. Patterns, changes, and trends in prescription opioid dispensing in Canada, 2005–2016. Pain Phys. 2018;21(3):219–28.

Webster LR, Fine PG. Review and critique of opioid rotation practices and associated risks of toxicity. Pain Med. 2012;13(4):562–70.

Nielsen S, Degenhardt L, Hoban B, Gisev N (2014) Comparing opioids: a guide to estimating oral morphine equivalents (OME) in research. Sidney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, University of NSW. Contract No.: 329

Stanos S. Evolution of opioid risk management and review of the classwide REMS for extended-release/long-acting opioids. Phys Sportsmed. 2012;40(4):12–20.

Health Quality Ontario. 9 Million prescriptions: what we know about the growing use of prescription opioids in Ontario. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2017.

Gomes T, Pasricha S, Martins D, Greaves S, Tadrous M, Bandola D, et al. Behind the prescriptions: a snapshot of opioid use across all Ontarians. Toronto: Ontario Drug Policy Research Network; 2017 August 22. p. 2017.

Dhalla IA, Persaud N, Juurlink DN. Facing up to the prescription opioid crisis. BMJ. 2011;343:d5142.

Coyle DT, Pratt C-Y, Ocran-Appiah J, Secora A, Kornegay C, Staffa J. Opioid analgesic dose and the risk of misuse, overdose, and death: a narrative review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2018;27(5):464–72.

Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley DN, Wang L, Couban RJ, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. Can Med Assoc J. 2017;189(18):E659–66.

Spooner L, Fernandes K, Martins D, Juurlink D, Mamdani M, Paterson JM, et al. High-dose opioid prescribing and opioid-related hospitalization: a population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0167479.

Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Dhalla IA, Mailis-Gagnon A, Paterson JM, Mamdani MM. Trends in opioid use and dosing among socio-economically disadvantaged patients. Open Med. 2011;5(1):e13–22.

Public Health Ontario. Interactive Opioid Tool: Opioid-related morbidity and mortality in Ontario Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion; 2020. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/substance-use/interactive-opioid-tool. Accessed 30 Aug 2020

Gomes T, Khuu W, Martins D, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, et al. Contributions of prescribed and non-prescribed opioids to opioid related deaths: population-based cohort study in Ontario. Can BMJ. 2018;362:k3207.

Fischer B, Jones W, Murphy Y, Ialomiteanu A, Rehm J. Recent developments in prescription opioid-related dispensing and harm indicators in Ontario. Can Pain Phys. 2015;18(4):E659–62.

Ali S, Tahir B, Jabeen S, Malik M. Methadone treatment of opiate addiction: a systematic review of comparative studies. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2017;14(7–8):8–19.

Fischer B, Jones W, Varatharajan T, Malta M, Kurdyak P. Correlations between population-levels of prescription opioid dispensing and related deaths in Ontario (Canada), 2005–2016. Prev Med. 2018;116:112–8.

King NB, Fraser V, Boikos C, Richardson R, Harper S. Determinants of increased opioid-related mortality in the United States and Canada, 1990–2013: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):e32–42.

Sauber-Schatz EK, Mack KA, Diekman ST, Paulozzi LJ. Associations between pain clinic density and distributions of opioid pain relievers, drug-related deaths, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and neonatal abstinence syndrome in Florida. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):161–6.

Heyward J, Olson L, Sharfstein JM, Stuart EA, Lurie P, Alexander GC. Evaluation of the extended-release/long-acting opioid prescribing risk evaluation and mitigation strategy program by the US food and drug administration: a review. JAMA Internal Med. 2020;180(2):301–9.

Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, Hall K, Stein CM. Prescription of long-acting opioids and mortality in patients with chronic noncancer pain. JAMA. 2016;315(22):2415–23.

Els C, Jackson TD, Kunyk D, Lappi VG, Sonnenberg B, Hagtvedt R, et al. Adverse events associated with medium- and long-term use of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;1(10):1.

Dasgupta N, Funk MJ, Proescholdbell S, Hirsch A, Ribisl KM, Marshall S. Cohort study of the impact of high-dose opioid analgesics on overdose mortality. Pain Med. 2016;17(1):85–98.

Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a national institutes of health pathways to prevention workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):276–86.

Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, Banta-Green CJ, Merrill JO, Sullivan MD, et al. Opioid prescriptions for chronic pain and overdose. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(2):85–92.

Fischer B, Jones W, Urbanoski K, Skinner R, Rehm J. Correlations between prescription opioid analgesic dispensing levels and related mortality and morbidity in Ontario, Canada, 2005–2011. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2014;33(1):19–26.

Gomes T, Juurlink D, Yao Z, Camacho X, Paterson JM, Singh S, et al. Impact of legislation and a prescription monitoring program on the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions for monitored drugs in Ontario: a time series analysis. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(4):E256–61.

Fischer B, Jones W, Rehm J. Trends and changes in prescription opioid analgesic dispensing in Canada 2005–2012: an update with a focus on recent interventions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):90.

Fischer B, Jones W, Tyndall M, Kurdyak P. Correlations between opioid mortality increases related to illicit/synthetic opioids and reductions of medical opioid dispensing—exploratory analyses from Canada. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):143.

Mars SG, Rosenblum D, Ciccarone D. Illicit fentanyls in the opioid street market: desired or imposed? Addiction. 2019;114(5):774–80.

Fischer B, Pang M, Jones W. The opioid mortality epidemic in North America: do we understand the supply side dynamics of this unprecedented crisis? Substance abuse treatment. Prev Policy. 2020;15(1):14.

Government of Canada. Opioid-related harms in Canada. Ottawa: Public Health Agency Can; 2020. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/problematic-prescription-drug-use/opioids/data-surveillance-research.html. Accessed 30 Aug 2020.

Belzak L, Halverson J. The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38(6):224–33.

Gisev N, Campbell G, Lalic S, Larney S, Peacock A, Nielsen S, et al. Current opioid access, use, and problems in Australasian jurisdictions. Curr Addict Rep. 2018;5(4):464–72.

Lam T, Kuhn L, Hayman J, Middleton M, Wilson J, Scott D, et al. Recent trends in heroin and pharmaceutical opioid-related harms in Victoria, Australia up to 2018. Addiction. 2020;115(2):261–9.

Roxburgh A, Hall WD, Dobbins T, Gisev N, Burns L, Pearson S, et al. Trends in heroin and pharmaceutical opioid overdose deaths in Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;179:291–8.

Berterame S, Erthal J, Thomas J, Fellner S, Vosse B, Clare P, et al. Use of and barriers to access to opioid analgesics: a worldwide, regional, and national study. Lancet (London, England). 2016;387(10028):1644–56.

Fischer B, Keates A, Bühringer G, Reimer J, Rehm J. Non-medical use of prescription opioids and prescription opioid-related harms: Why so markedly higher in North America compared to the rest of the world? Addiction. 2014;109(2):177–81.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Benedikt Fischer acknowledges research support from the endowed Hugh Green Foundation Chair in Addiction Research, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, New Zealand. This work was further partially supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grant #SAF-94814, which also covered the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Benedikt Fischer, Dimitri Daldegan-Bueno, and Wayne Jones have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fischer, B., Daldegan-Bueno, D. & Jones, W. Comparison of Crude Population-Level Indicators of Opioid Use and Related Harm in New Zealand and Ontario (Canada). Pain Ther 10, 15–23 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00229-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00229-6