Abstract

Chronic refractory central post-stroke pain (CPSP), one of the most disabling consequences of cerebral stroke, occurs in up to 10% of patients with CPSP. Because a considerable proportion of these patients with chronic pain remain resistant to pharmacological and behavioral therapies, adjunctive invasive and non-invasive brain stimulation therapies are needed. We performed a review of human studies applying burst and conventional motor cortex stimulation (burstMCS and cMCS, respectively) for chronic pain states, on the basis of data sources identified through searches of PubMed, MEDLINE/OVID, and SCOPUS, as well as manual searches of the bibliographies of known primary and review articles. Our aim was to review and discuss clinical data on the indications of burstMCS for various chronic pain states originating from central stroke (excluding trigeminal facial pain). In addition, we assessed the efficacy and safety of burst versus cMCS for central post-stroke pain with an extended follow-up of 5 years in a 60-year-old man. According to our review, uncontrolled observational human cohort studies and one RCT using cMCS waveforms have revealed a meaningful clinical response; however, these studies lacked placebo groups and extended observation periods. In our case report, we found that 3 months of adjunctive cMCS reduced pain levels [visual analog scale (VAS) pre: 9/10 versus VAS post 7/10], whereas the pain decreased further under burstMCS (VAS pre: 7/10 versus VAS post: 2/10); the study involved a follow-up of 5 years and the following parameters: burst rate 40 Hz (500 Hz), 1–1.75 mA, 1 ms, bipolar configuration. To date, only limited evidence exists for the efficacy and safety of burst motor cortex stimulation for the treatment of refractory chronic pain. BurstMCS resulted in significantly decreased post-stroke pain observed after 5 years of cMCS. The available literature suggests similar efficacy as that of conventional (tonic) motor cortex stimulation, although the results are preliminary. Mechanistically, the precise mechanism of action is not fully understood. However, burstMCS may interact with the nociceptive thalamic-cingulate and descending spinal pain networks. To determine the potential utility of this treatment, large-scale sham-controlled trials comparing cMCS and burstMCS are highly recommended.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Conventional motor cortex stimulation yielded meaningful pain suppression in refractory trigeminal facial pain and post-stroke pain. |

Preliminary clinical data indicate burst motor cortex stimulation to be safe and efficient. |

Novel waveforms such as burst motor cortex stimulation deserve enhanced attention. |

Comparative sham-controlled trials using conventional and burst stimulation are warranted. |

Electrical (transcranial magnetic stimulation) and pharmacological drugs (e.g. morphine, ketamine) may help to predict motor cortex stimulation outcome. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13235165.

Introduction

Pharmacological and behavioral interventions are the first-line treatments for chronic central pain (CPP), particularly for the post-stroke pain occurring in up to 10% of patients with cerebral stroke [1]. A substantial portion of patients with CPPs develop refractory pain with unfavorable responses to established conservative therapy. Brain stimulation, both non-invasive [transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), transcranial direct current stimulation, transcranial alternating stimulation, transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation], minimally invasive [motor cortex stimulation (MCS)], and invasive [deep brain stimulation (DBS)], has been reported to yield response rates ranging from 25 to 45%. Epidural MCS appears to be superior to DBS of the thalamus or brainstem, and it is used more frequently because of its easier and less invasive application and its wider range of indications [2,3,4,5]. A recent MCS study applying a conventional MCS (cMCS) pattern in a series of 16 patients with a mean follow-up of 28 months reported pain relief regardless of the type of stroke/location [6]. cMCS waveforms have been widely used for a broad variety of chronic pain conditions including post-stroke pain, facial pain, trigeminal neuralgia, and neuropathic pain of the limbs (different origin), and for some movement disorders, mainly tremor and Parkinson’s disease [1, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Preliminary clinical data indicate that epidural MCS and TMS are superior to DBS of the thalamus or brainstem, although randomized controlled comparative human studies have not been reported [5, 14, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. In general, adjunctive cMCS has been found to evoke substantial clinical pain suppression associated with a lower risk profile than more invasive neuromodulation approaches through DBS. Regardless of the applied minimally invasive and invasive brain stimulation therapies (MCS and DBS), non-invasive brain stimulation techniques (TMS, transcranial direct current stimulation, transcranial alternating stimulation, or vagus nerve stimulation) should be considered and explored before invasive brain stimulation [6, 17].

First, clinical uncontrolled case series data have suggested that the application of burst waveforms for MCS along with a tonic MCS pattern is reasonably safe [19]. Currently available neurostimulation devices would facilitate this approach and notably enable assessment of the efficacy of different MCS paradigms in sham-controlled studies, as previously reported for burst SCS targeting drug-resistant chronic pain and movement disorders [30,31,32] (see Table 1).

BurstDR™, a relatively novel stimulation waveform, has been approved and is mainly used for spinal cord stimulation treatment of various pain conditions [30,31,32]. Here, we present our long-term comparative findings in a single patient with CPP treated with an MCS approach, assessing the effects of cMCS versus burstMCS waveforms on the neuropathic pain levels observed over a 5-year period. Furthermore, we provide a comprehensive overview of the state of the art and existing evidence of the therapeutic effects of MCS (cMCS and/or burstMCS) as an adjunctive treatment for CPP (excluding trigeminal facial pain). In addition, we describe the relevant literature providing insights into the mechanism of action of MCS on pain neural transmission. Our aim in this review is to highlight the capabilities of currently available MCS modalities that can deliver different waveforms relevant for chronic pain control.

Methods

We performed a narrative review with searches of PubMed, MEDLINE/OVID, and SCOPUS, as well as manual searches of the bibliographies of known primary and review articles, from the years 1990–2020. Other data comprised manual searches of publications, including concepts of burst stimulation waveforms targeting the sensorimotor cortex, with an emphasis on clinical studies, on the basis of the following search terms: motor cortex stimulation, burst waveform, tonic stimulation, chronic central pain, neuropathic pain, post-stroke pain, prediction, non-invasive brain stimulation, and randomized controlled trials. Clinical studies focused on results for various parameters including visual analog scale (VAS) scores as well as individual functional outcomes. Trigeminal facial pain was excluded as a potential indication for MCS. This narrative review is accompanied by a single-case report of burstMCS applied over a long-term period of 5 years in a patient with post-stroke pain. Owing to the limited scope of studies with meta-analysis, and to the clinical heterogeneity and methodological diversity across studies, we believed that a large-scale meta-analysis would have limited scope and value. The patient consented to publication of his data. The case report was written in accordance with Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) guidelines, and it complies with the CARE statement.

Results

Patient History and Neurological State

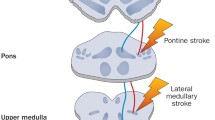

A 60-year-old man had chronic refractory neuropathic CPP due to a right-side posterior thalamic stroke of cardio-embolic origin (stroke onset at the age of 55 years). Over 2 years, the patient developed progressive, persistent, and painful hemi-dysesthesia along with allodynia of the upper limbs. Before MCS implantation, routinely performed MRI scans (5 years post-stroke) showed an irregularly shaped T2-hyperintense embolic lesion at the dorsal thalamic area (sensory nuclei, pulvinar). Additionally, diffusion tensor imaging MR data confirmed diffusion restriction and damage to the white matter structures due to the ischemic lesion in this area (Fig. 1a–d). Neurological examination indicated no functional impairment beyond mild ataxia. Neuropathic pain affected the left-side upper and lower extremities, and manifested as sharp, burning paresthesia and more pronounced allodynia in the upper limb. Multimodal pain therapy administered at the university pain center (neurology and anesthesiology), including pharmacological/behavioral and non-invasive brain stimulation (TMS) approaches, achieved limited response. Baseline pain medication included pregabalin 100 mg/day and tilidate 100 mg/day. Because the thalamic lesion was located in the sensory nuclei of the thalamus, DBS of the thalamic nuclei was not considered; hence, the patient was referred for epidural brain stimulation by MCS. Invasive MCS was applied on the basis of interdisciplinary pain board approval for use of cMCS and burstMCS paradigms. Ethical review board approval was not applicable, because MCS was considered the last treatment option. The patient was not notified about the time of stimulation mode change, because he had provided written informed consent before the implantation.

a–d Axial T2-weighted MRI image on admission demonstrated an ischemic lesion in the dorsal part of the thalamus, located between the sensory thalamic nuclei and the pulvinar of the thalamus. b Axial T1-weighted with Gd contrast-enhanced MRI sequence showing the ischemic lesion in the dorsal part of the thalamus. c Axial FLAIR (fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) MRI image on admission demonstrated an ischemic lesion in the dorsal part of the right-side thalamus. d Axial diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) MR data, evaluated as a color-coded water diffusion directionality map, demonstrate destruction of white matter fiber tracts in the right-side dorsal part of the thalamus, as indicated by the ellipse. (Color code: blue, feet-to-head direction; green, anterior-to-posterior direction; and red, left-to-right direction)

Operative Procedure

Under general anesthesia (without relaxation), a 16-contact paddle lead (5-column array 46 mm × 11 mm × 2 mm; PENTA, Abbott Inc., Plano, TX, USA) was implanted in the patient. The burst stimulation device/pattern was applied and marked for spinal cord stimulation. Target accuracy was determined in a frame-based manner (Leksell frame; Elekta AB, Sweden) that accurately revealed the appropriate entry and target zones with MR/CT-fusion (T1 contrast-enhanced, T2, FLAIR), and the procedure was performed under guidance by electrophysiological mapping (motor-evoked potential MEP; somato-sensory evoked potential SSEP phase reversal). Subsequently, the paddle lead was connected via an extension wire (Abbott Inc. Plano, TX, USA) to a subcutaneous subclavicularly implanted, rechargeable IPG (Prodigy IPG; Abbott Inc., Plano, TX, USA) able to perform cMCS and burstMCS patterns. On the basis of the patient’s relatively greater upper limb-associated pain, and the hemibody neuropathic pain, we decided where on the motor homunculus to center a perpendicularly placed electrode, given that the upper and lower extremities were unlikely to be covered by a single paddle-like electrode. Postoperative sequential CT scans indicated that the perpendicularly placed electrode was slightly anterior to the central strip.

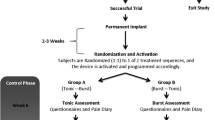

Postoperative Stimulation Protocol and MCS Responsiveness

Phase 1 (cMCS) was administered for the first 3 months with the following stimulation parameters: 1–2.75 mA intensity (stimulation intensity starting at 20% of the motor threshold and subsequently increased to 80% of the motor threshold), 4−, 6+ , 8+ , 10−, bipolar configuration, 90–180 μs, and 40–50 Hz. The activated contacts were chosen according to the anatomical locations to ensure sufficient stimulation of the arm motor strip. After 3 months of cMCS, the stimulation mode was switched to phase 2 (burstMCS) in a single-blinded fashion with the following parameters: burst rate 40 Hz, intra-burst 500 Hz, 1–1.75 mA intensity (stimulation parameters were adjusted once per month), pulse width 1 ms, and unchanged polarities (fixed active contact).

Adjunctive cMCS ameliorated the patient’s pain levels, as quantified by the VAS after 3 months [arm pain: baseline VAS 9/10 versus 7/10 (22% reduction); leg pain: VAS 9/10 to VAS 8/10 (11% reduction)]. After switching to burstMCS for an additional 60 months, we observed an increase in pain suppression (arm pain: baseline VAS 7/10 versus 2/10; leg pain: VAS 8/10 to VAS 1/10) along with discontinuation of the pre-implantation pain medication (Fig. 2). No implantation- and/or stimulation-associated adverse events occurred. While the stimulation intensities increased under both MCS patterns, no MCS-evoked seizures were observed.

Discussion

-

1.

Summary of Our Long-Term Observations and Comparison with Published Human Studies Addressed to Different MCS Waveforms for Post-Stroke Pain

We first determined the long-term effects of burstMCS for refractory CPP adjunctive to cMCS and pharmacological therapy. Meaningful pain suppression was achieved after combined cMCS/burstMCS without stimulation-related side effects (e.g., seizure).

Our findings confirmed those of a small-scale MCS study reporting similar results despite a shorter observation period [8]. In addition, adjunctive pain medication (pregabalin) was removed after 7 months; this medication is usually prescribed as adjunctive pharmacological seizure treatment. The results during the observation period (60 months) should be interpreted with caution, because the effects of MCS are well known to deteriorate over longer time frames. In general, the lack of a sham treatment period (MCS “off”) limits our findings, because our patient was not blinded to the activation of the device. Furthermore, a trial period was not performed, because MCS responsiveness in general appears to occur over relatively long time periods of weeks rather than days. To date, no evidence exists either in favor of or against the true value of MCS trials, particularly in view of the long-term responsiveness to MCS. The lead location may explain the clinical observations and support an enhanced response in the upper limb.

The concept of applying electrical stimulation targeting the motor cortex dates to the early 1970s, and was an incidental consequence of observations made by Penfield and colleagues in epilepsy surgery resecting the postcentral gyrus. In later years, extension of the resection area toward the precentral strip was found to promote sufficient pain suppression [4]. Although cMCS has been applied in a broad variety of chronic pain disorders, trigeminal facial pain and post-stroke pain exhibit the highest degree of responsiveness and are classified as the two major indications for cMCS [14, 15].

Since the pioneering work of Yamamoto and colleagues, several uncontrolled cohort studies have confirmed that cMCS is safe and efficient for the treatment of post-stroke pain and trigeminal facial pain. Notably, among hardware-related failures or dysfunction, seizure, implant infection, and rarely post-implant hematomas have been observed after MCS surgery. Despite several recommendations, MCS therapy has been performed with heterogeneous implantation techniques, because some physicians prefer to perform MCS surgery according to intraoperative neurophysiologic recordings, whereas others use neuroimaging (functional sequences). In addition, some surgeons approach the central cortex area via a burrhole rather than performing more invasive craniotomy, and assess trial test stimulations before permanent MCS implantation; however, consensus is lacking regarding the usefulness and predictive value of a trial period for MCS treatment [6, 7, 9,10,11, 13, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Velasco et al. performed the only existing randomized sham-controlled study in a heterogeneous, small cohort of patients with chronic neuropathic pain, with an observation period of 12 months [13]. Most enrolled patients with pain had postherpetic neuralgia, and one patient had post-stroke pain (thalamic infarct). However, after 1 year, the participants with post-stroke pain perceived a significant reduction in pain (69%) with respect to allodynia and hyperalgesia, whereas pre-MCS hypesthesia remained unchanged, with the following MCS parameters: 40 Hz, 90 µsec, and 2.0–6.5 V [13].

In general, in view of the invasiveness of cMCS, efforts have been made to provide potential predictive measures for cMCS responsiveness [5, 29]. Yamamoto and co-workers have determined the predictive potential of pre-implantation pharmacological drugs such as morphine, thiamylal, and ketamine, and have demonstrated that patients with neuropathic pain who are sensitive to thiamylal and ketamine, and insensitive to morphine, display pronounced long-lasting cMCS responsiveness, thus indicating the potential utility of analgesic drugs in predicting cMCS outcome. However, these remarkable findings have not been further re-examined on a systemic evidence-based level [29].

TMS is a non-invasive first-line neuromodulation treatment in different drug-resistant chronic pain disorders; its response rate depends on parameters such as TMS frequency and the location of the lesion. In contrast to MCS treatment, previously performed TMS did not elicit a response in our patient; however, the available published literature indicates controversial findings regarding the predictive value of TMS before MCS implantation [1, 3]. MCS parameters for central post-stroke pain (CPSP) have usually been kept at frequencies between 1 and 20 Hz, and resulted in a broad response rate of 30–50% in CPSP [1, 6].

According to several human studies, non-invasive TMS targeting the motor cortex has used different frequencies (1 Hz–20 Hz), and better outcomes have been reported for 20 Hz-driven TMS. Notably, in some cases, 1 Hz TMS has been reported to increase pain intension/perception, whereas treatment with 20 Hz TMS elicits a sufficient response; more interestingly, cMCS implantation later in the course of pain treatment has achieved sustained cMCS outcomes [3, 5].

-

2.

Mechanistic Insights into the Effects of Tonic and BurstMCS on Brain Pain Circuits Originating from Central Stroke

Along with observational cohort studies supporting the use of cMCS for chronic pain—in which trigeminal facial pain and post-stroke pain are classified as the most suitable disorders—neuroimaging studies (PET) and electrophysiological measures have shown that several brain areas are relevant to the mechanism of action of cMCS, including the thalamus, cingulate cortex, brainstem, orbitofrontal cortex, and, via descending pain-inhibiting pathways, the corticospinal tract [4].

Electrophysiological studies have shown that irregular burst discharges are often encountered in the posterolateral thalamus in patients with central thalamic pain after stroke. The more often irregular burst discharges are encountered, the greater the decrease in sensory response in the posterolateral thalamus. Decreased activity with abnormal burst discharge in the posterolateral sensory thalamus has been suggested to be associated with changes in cortical activity adjacent to the central sulcus, which might contribute to the generation of central thalamic pain [4]. The ischemic lesion in our case report occurred between the ventral posterolateral nucleus and the pulvinar of the thalamus. In addition, because of thalamic stroke affecting the sensory nuclei–pulvinar zone of the thalamus, MCS appears likely to modulate parts of the medial thalamic pain pathway, which was not affected after stroke in our case. In addition, the cingulate cortex, brainstem, and corticospinal tracts have been suspected to play a key role in neural pain transmission and processing [8].

Although the precise mechanism of action of MCS remains to be established, experimental studies have provided valuable insights. Through behavioral tasks, immunohistochemistry (c-fos and serotonin expression), micro-PET, and electrophysiological recording, MCS has been found to alter c-fos/serotonin expression and activity in the thalamus, the periaqueductal grey, and the cerebellum. In addition, neuronal activity in the thalamic nuclei, which are responsible for sensory processing (nucleus ventralis posterolateralis), was induced by mechanical stimulation but was reversed by MCS treatment. These interesting experimental findings may partly explain the effects of MCS observed in humans, involving ascending and descending central circuits relevant to neural pain transmission [33]. MCS using a burst stimulation pattern may interact with thalamo-cingulate plasticity, particularly with the intra-laminar nuclei of the thalamus, a key relay structure associated with pain attention [4, 34]. A burst-firing pattern of the thalamus (burst hyperactivity) may evoke short- and/or long-term plasticity in connected circuits such as the nociceptive thalamic-anterior cingulate pathway. The medial thalamic complex, for instance, is believed to potentiate anterior cingulate cortex neuronal activity through its burst-firing pattern. Such neuronal transmission enables temporal response and processing of peripheral persisting noxious stimuli (e.g., pain). The transition from acute to chronic pain may be a result of the dysrhythmicity of the thalamic-cingulate network responsible for pain attention and pain-induced fear/anxiety behavior [34, 35]. Of note, previously applied cMCS may have evoked a priming effect for further pain reduction, as observed under secondarily applied burstMCS in our report. Therefore, both MCS patterns (conventional and burst) may interact and induce changes in the neural transmission from the thalamus to the anterior cingulate cortex and back [4]. Beyond its effects on the sensory brain and spinal cord pathways, MCS has been suggested to modulate pain attention by affecting orbitofrontal areas [36].

-

3.

Pros and Cons of Minimally Invasive and Invasive Central Neurostimulation Therapies for Chronic Pain through MCS And DBS

Although consensus is lacking regarding standardized implantation techniques, stimulation parameters and outcome assessment, minimally invasive MCS and invasive DBS have been widely used to treat chronic pain conditions of different origins, leading to limited evidence, acceptance, comparability, recommendation, and interpretation of positive and negative outcomes of MCS and DBS. Various DBS targets have been explored, such as the thalamic sensory nuclei (ventralis posterolateralis), thalamic affective nuclei (centrum medianum parafascicularis), anterior cingulate cortex, periaqueductal grey, and most recently the posterior limb of the internal capsule [37,38,39]. Preliminary data from a study assessing thalamic DBS and MCS in neuropathic patients found similar effectiveness for brain stimulation modalities in a small cohort [39]. However, the results have led to several concerns and promoted an ongoing debate regarding simultaneous combined MCS–DBS approaches instead of performing less invasive MCS before DBS [40, 41].

-

4.

Proposal for Future Targeted MCS Clinical Trial Protocol

In the past, the main criticism in neurostimulation trials has been the lack of control groups (sham stimulation) to exclude and/or characterize the placebo effect, which is known to promote pain suppression in a substantial portion of treated people [42, 43]. Although, for various reasons, some difficulties have arisen with the inclusion of sham-surgery/-stimulation, currently available MCS systems allow for easily performed sham stimulation and should be considered in further MCS trials comparing different waveforms (e.g., tonic versus burst). Hence, future targeted MCS clinical research should seek to classify and include potentially valuable predictive methodologies, such as TMS, to further investigate the effects of analgesic drugs, and to explore placebo control groups. All the described strategies would contribute to and extend current knowledge of relevant MCS induced changes in chronic pain pathways [3, 5, 29, 42, 43].

Conclusions

cMCS has been found to effectively decrease neuropathic chronic pain associated with central stroke in many uncontrolled observational studies, with fewer complications than more invasive DBS procedures for various targets. Preliminary data derived from small-scale studies support the extension of MCS treatment to novel waveforms, particularly BurstDR MCS. The principal limitation of this study is that we report observations in a single patient, and therefore the results are difficult to generalize. BurstMCS appears to have a potentially clinically meaningful effect. This comparative case report did not provide clear evidence against or in favor of each applied MCS mode, but was intended to serve as a basis for future targeted clinical trials to determine the potential utility of this method. We recommend re-visiting this open question in large-scale sham-controlled comparative MCS trials (burst versus tonic versus sham) and to quantify the possible effects on deeper brain circuits using functional/structural neuroimaging and electrophysiological strategies.

References

Hosomi K, Seymour B, Saitoh Y. Modulating the pain network-neurostimulation for central poststroke pain. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):290–9.

Nguyen JP, Nizard J, Keravel Y, Lefaucheur JP. Invasive brain stimulation for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7(12):699–709.

Lefaucheur JP, Drouot X, Kéravel Y, Nguyen JP. Pain relief induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of precentral cortex. NeuroReport. 2001;12:2963–5.

Brown JA, Barbaro NM. Motor cortex stimulation for central and neuropathic pain: current status. Pain. 2003;104:431–5.

Andre-Obadia N, Peyron R, Mertens P, Mauguière F, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for pain control. Double-blind study of different frequencies against placebo, and correlation with motor cortex stimulation efficacy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:1536–44.

Zhang X, Hu Y, Tao W, Zhu H, Xiao D, Li Y. The effect of motor cortex stimulation on central poststroke pain in a series of 16 patients with a mean follow-up of 28 months. Neuromodulation. 2017;20(5):492–6.

Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Yamamoto T, Hirayama T, Koyama S. Chronic motor cortex stimulation in patients with thalamic pain. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(3):393–401. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1993.78.3.0393.

Peyron R, Garcia-Larrea L, Petal DM. Electrical stimulation of precentral cortical area in the treatment of central pain: electrophysiological and PET study. Pain. 1995;62(3):275–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(94)00211-V].

Nguyen JP, Lefaucher JP, Le Guerinel C, et al. Motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of central and neuropathic pain. Arch Med Res. 2000;31(3):263–5.

Velasco M, Velasco F, Brito F, et al. Motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of differentiation pain. I. Localization of the motor cortex. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2002;79:146–67.

Rasche D, Ruppolt M, Stippich C, Unterberg A, Tronnier VM. Motor cortex stimulation for long-term relief of chronic neuropathic pain: a 10 year experience. Pain. 2006;121(1–2):43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.006.

Zabek M, Slawek J, Harat M, et al. Stimulation of the brain and spinal cord to treat movement disorders and pain syndromes - theoretical and practical recommendations. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2006;40(1):1–9.

Velasco F, Arguelles C, Carrillo-Ruiz JD, et al. Efficacy of motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of neuropathic pain: a randomized double-blind trial. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(4):698–706. https://doi.org/10.3171/JNS/2008/108/4/0698.

Levy R, Deer TR, Henderson J. Intracranial neurostimulation for pain control. Pain Physician. 2010;13(2):157–65.

Rasche D, Tronnier VM. Clinical significance of invasive motor cortex stimulation for trigeminal facial neuropathic pain syndromes. Neurosurgery. 2016;79(5):655–66.

De Ridder D, Vanneste S, Van Laere K, Menovsky T. Chasing map plasticity in neuropathic pain. World Neurosurg. 2013;80(6):e901–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2012.12.009.

Sokal P, Harat M, Zielinski P, Furtak J, Paczkowski D, Rusinek M. Motor cortex stimulation in patients with chronic central pain. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2015;24(2):289–96.

Henssen DJHA, Kurt E, van Walsum AMVC, et al. Long-term effect of motor cortex stimulation in patients suffering from chronic neuropathic pain: an observational study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0191774. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191774.

Sokal P, Harat M, Malukiewicz A, Switonska M, Jablonska R. Effectiveness of tonic and burst motor cortex stimulation in chronic neuropathic pain. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1863–9.

Brown JA. Motor cortex stimulation. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;11(3):E5.

Kurt E, Henssen DJHA, Steegers M, Staal M, Beese U, Maarrawi J, et al. Motor cortex stimulation in patients suffering from chronic neuropathic pain: summary of expert meeting and premeeting questionnaire, combined with literature review. World Neurosurg. 2017;108:254–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.08.168.

Cioni B, Meglio M. Motor cortex stimulation for chronic non-malignant pain: current state and future prospects. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97(Pt 2):45–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-211-33081-4_5.

Lazorthes Y, Sol JC, Fowo S, Roux FE, Verdié JC. Motor cortex stimulation for neuropathic pain. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97(Pt 2):37–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-211-33081-4_4.

Nguyen JP, Lefaucheur JP, Decq P, Uchiyama T, Carpentier A, Fontaine D, et al. Chronic motor cortex stimulation in the treatment of central and neuropathic pain. Correlations between clinical, electrophysiological and anatomical data. Pain. 1999;82(3):245–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00062-7.

Nguyen JP, Lefaucheur JP, Le Guerinel C, Fontaine D, Nakano N, Sakka L, et al. Treatment of central and neuropathic facial pain by chronic stimulation of the motor cortex: value of neuronavigation guidance systems for the localization of the motor cortex. Neurochirurgie. 2000;46(5):483–91.

Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Yamamoto T, Hirayama T, Koyama S. Chronic motor cortex stimulation for the treatment of central pain. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1991a;52:137–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7091-9160-6_37.

Tsubokawa T, Katayama Y, Yamamoto T, Hirayama T, Koyama S. Treatment of thalamic pain by chronic motor cortex stimulation pacing. Clin Electrophysiol. 1991b;14(1):131–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.1991.tb04058.x.

Katayama Y, Tsubokawa T, Yamamoto T. Chronic motor cortex stimulation for central deafferentation pain: experience with bulbar pain secondary to Wallenberg syndrome. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1994;62(1–4):295–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000098635.

Yamamoto T, Katayama Y, Hirayama T, Tsubokawa T. Pharmacological classification of central post-stroke pain: comparison with the results of chronic motor cortex stimulation therapy. Pain. 1997;72(1–2):5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00028-6.

Pintea B, de Boni L, Kinfe TM. Subperceptional burst versus perceptional tonic spinal cord stimulation waveforms for drug-resistant orthostatic tremor: comparative data of 2 cases. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2017;4(4):612–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/mdc3.12485.

Chakravarthy KV, Chaturvedi R, Agari T, Iwamuro H, Reddy R, Matsui A. Single arm prospective multicenter case series on the use of burst stimulation to improve pain and motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Bioelectron Med. 2020;6:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42234-020-00055-3 ((eCollection 2020)).

Chakravarthy K, Kent A, Raza A, Fang X, Kinfe TM. Burst spinal cord stimulation: Review of preclinical studies and comments on clinical outcomes. Neuromodulation. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/ner.12756.

Kim J, Ryu SB, Lee SE, et al. Motor cortex stimulation and neuropathic pain: how does motor cortex stimulation affect pain-signaling pathways? J Neurosurg. 2016;124(3):866–76. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.1.JNS14891.

Bliss TV, Collingridge GL, Kaang BK, Zhuo M. Synaptic plasticity in the anterior cingulate cortex in acute and chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(8):485–96.

Shyu B-C, Vogt BA. Short-term synaptic plasticity in the nociceptive thalamic-anterior cingulate pathway. Mol Pain. 2009;5:51. https://doi.org/10.1186/17744-8069-5-51.

Garcia-Larrea L, Peyron R. Motor cortex stimulation for neuropathic pain: from phenomenology to mechanisms. Neuroimage. 2007;37(Suppl):S71–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.062.

Honey CM, Tronnier VM, Honey CR. Deep brain stimulation versus motor cortex stimulation for neuropathic pain: A minireview of the literature and proposal for future research. Comput Struct Biotech. 2016;14:234–7.

Franzini A, Messina G, Levi V, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the posterior limb of the internal capsule in the treatment of central poststroke neuropathic pain of the lower limb: case series with long-term follow-up and literature review. Neurosurg. 2019;16:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.5.JNS19227.

Son BC, Kim DR, Kim HS, Lee SW. Simultaneous trial of deep brain and motor cortex stimulation in chronic intractable neuropathic pain. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2014;92(4):218–26. https://doi.org/10.1159/000362933.

Lévêque M, Weil AG, Nguyen JP. Simultaneous deep brain stimulation/motor cortex stimulation trial for neuropathic pain: fishing with dynamite? Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93(3):219. https://doi.org/10.1159/000368198.

Son BC. Reply to the letter by Lévêque et al. Entitled ’simultaneous deep brain stimulation/motor cortex stimulation trial for neuropathic pain: fishing with dynamite? Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2015;93(3):220–1. https://doi.org/10.1159/000375436.

Kjaer SW, Rice ASC, Wartolowski K, Vase L. Neuromodulation: more than a placebo effect? Pain. 2020;161:491–5.

Banik RK. Therapeutic benefits of placebo surgery and challenges in neuromodulation research. Pain. 2020;161(8):1937–9.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participant in the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

TMK conducted the study, drafted the manuscript, and edited and approved the final version. MB, AS, MN, AM, SC, and MH edited the manuscript.

Disclosures

Thomas Kinfe, MD, PhD, works as a consultant for Medtronic Inc., Abbott Inc. and has been paid for presentation and received conference travel support from Abbott Inc. Martin Nüssel, Melanie Hamperl, Anna Maslarova, Shafqat R. Chaudhry, Julia Köhn, Andreas Stadlbauer and Michael Buchfelder have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The patient consented to publication of his data. The case report was written in accordance with COPE guidelines, and it complies with the CARE statement.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nüssel, M., Hamperl, M., Maslarova, A. et al. Burst Motor Cortex Stimulation Evokes Sustained Suppression of Thalamic Stroke Pain: A Narrative Review and Single-Case Overview. Pain Ther 10, 101–114 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00221-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00221-0