Abstract

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic pain condition characterized by impaired emotional regulation. This study explored the brain response to pain-related fear as a potential brain signature of FM.

Methods

We used a conditioned fear task and magnetoencephalography to record pain-related fear responses in patients with FM. Two blocks of 30 fear responses were collected to compute the response strength in the first block and the strength difference between the first and second blocks (fear habituation). These measurements were investigated for their clinical relevance and compared with measurements obtained from healthy controls and patients with chronic migraine (CM), a different chronic pain condition often comorbid with FM.

Results

Pain-related fear clearly activated the bilateral amygdala and anterior insula in patients with FM (n = 52), patients with CM (n = 50), and the controls (n = 30); the response strength in the first block was consistent across groups. However, fear habituation in the right amygdala decreased in the FM group (vs. CM and control groups, both p ≤ 0.001, no difference between CM and control groups). At the 3-month follow-up, the patients with FM reporting < 30% improvement in pain severity (n = 15) after pregabalin treatment exhibited lower fear habituation in the left amygdala at baseline (vs. ≥ 30% improvement, n = 22, p = 0.019). Receiver operating characteristic analysis confirmed that amygdala fear habituation is a suitable predictor of diagnosis and treatment outcomes of FM (area under the curve > 0.7).

Conclusions

Amygdala activation to pain-related fear is maladaptive and linked to treatment outcomes in patients with FM. Because the aberrant amygdala response was not observed in the CM group, this response is a potential brain signature of FM.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier, NCT02747940.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a disabling idiopathic chronic pain condition characterized by emotional dysregulation; however, few studies have explored the functional changes of the limbic system or neural substrates of emotional processing in patients with FM. |

Innovative methods involving magnetoencephalography and a conditioned fear task were used to obtain direct neural activity from the amygdala to advance current understanding of pain-related fear in FM and chronic migraine (CM); response to pregabalin treatment in patients with FM was followed to verify the amygdala fear response as a potential brain signature for FM diagnosis and prognosis. |

Pain-related fear clearly activated the bilateral amygdala and anterior insula in patients with FM, those with CM, and controls. Notably, fear habituation in the right amygdala decreased in the patients with FM (vs. those with CM and controls); no difference was detected between the patients with CM and controls. |

After 3 months of pregabalin treatment, the patients with FM patients who reported ≥ 30% improvement in pain severity exhibited a higher degree of fear habituation in the left amygdala relative to those who reported < 30% pain improvement. |

Receiver operating characteristic analysis confirmed that amygdala fear habituation is a suitable predictor of diagnosis and treatment outcomes of FM. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13033109.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a common chronic pain disorder of the central nervous system with an estimated prevalence of 2% in the general population [1]. FM is characterized by abnormal nociceptive sensory processing and the inability to modulate pain effectively; therefore, it results in chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain and clinical symptoms of centralized pain, including headache, fatigue, sleep disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, and depression [2]. To date, a biomarker for FM has not yet been identified. Therefore, FM diagnosis depends on clinical assessments and questionnaires.

Although FM pathophysiology remains elusive, a peripheral nerve component as well as cytokine and nerve growth factor involvement have been explored [3]. Psychological components such as stress can augment pain. Thus, several studies have highlighted the role of impaired emotional regulation in FM, particularly that of pain-related fear [4,5,6]. Clinically, pain-related fear is a risk factor for chronic pain development and persistence and a proposed target for interventive treatment [7]. In patients with FM, pain-related fear and resultant emotional distress may further affect disease severity, functional disability, pain threshold, and pain tolerance [8]. Similarly, the neural circuitry associated with emotional regulation, namely the limbic system, has also exhibited structural and functional changes in neuroimaging studies on FM [9,10,11,12]. Specifically, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional MRI (fMRI) have been used to gather evidence of changes in brain morphology (white and gray matter) and activity in patients with FM [13]. Moreover, symptoms of FM include sleep disturbance and emotional dysregulation, and amygdala activity is a key factor regulating both sleep and emotion [14]. Patients with FM have exhibited altered limbic functionality as well as reductions in gray matter volume within the amygdala in neural activity and connectivity studies [13, 15, 16]. Regarding prognosis, pregabalin can reduce chronic pain intensity as well as glutamatergic and neuronal activity within the posterior insula of patients with FM [17].

Fear conditioning is a standard paradigm for revealing the neural processing of pain-related fear [18]. In patients with chronic pain, fear conditioning induces emotion-related behavioral changes, such as impaired perceptual discrimination [19] and augmented fear generalization [4]. Patients with FM have been reported to show slower fear acquisition in a predictable context and faster fear acquisition in an unpredictable context [4] as well as a larger degree of change in heart rate [6], all compared with these factors in controls. However, the neural substrates, response patterns, pathophysiological links, and clinical relevance of aberrant emotional regulation in patients with FM remain unknown. Positron emission tomography (PET) and fMRI studies in healthy volunteers have indicated that the main brain regions mediating the learning and extinction of pain-related fear are the amygdala [20,21,22], anterior insula [23,24,25], and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) [26]. These three areas involved in emotional regulation have exhibited neuroplastic changes in patients with various types of chronic pain [27,28,29,30]. Whether neural responses underpinning pain-related fear exhibit identical spatiotemporal patterns across different types of chronic pain remains unresolved.

Notably, studies have investigated sensory processing in FM through somatosensory or auditory stimulation and have demonstrated that sensory habituation, which is a reduction in response to repeated stimuli, was reduced in the central neuropathology of chronic pain [31,32,33]. Although emotional regulation plays a central role in FM, the neural associations of pain-related fear habituation (i.e., the suppression of affective pain responses) have not yet been investigated. Therefore, by using an advanced neuroimaging technique with fine temporal and spatial resolution, this study first examined the dynamic neural activities underlying pain-related fear processing and hypothesized that FM is associated with aberrant brain habituation of pain-related fear. This association may be linked to the clinical profiles of FM. The present study used magnetoencephalography (MEG) to record neural responses to a conditioned fear acquisition task and the dynamic and temporospatial activation of neural substrates underpinning pain-related fear. Compared with conventional scalp electroencephalography, MEG exhibits superior localization and measurement of brain activities in the cortical as well as subcortical regions. Moreover, MEG outperforms fMRI in studies of temporal fluctuation in brain activity because of its high temporal resolution [34]. In addition, here, we enrolled patients with chronic migraine (CM), a different chronic pain condition, to explore whether the aberrant brain processing of pain-related fear is a distinct feature of FM or common across chronic pain disorders. We selected CM because it is a common comorbidity with FM, and the two chronic pain disorders have similar pathophysiology, disease severity, and prevalence in the general population [35,36,37].

The specific aims of the current study were to (a) characterize the dynamic brain activation of pain-related fear responses in patients with FM and compare activation and habituation patterns with those of healthy controls and patients with CM; (b) investigate the association of pain-related fear responses with the clinical profile of FM, including pain severity, emotion, stress, functional disability, and treatment outcome; and (c) explore the predictive value of pain-related fear response in FM diagnosis and treatment outcomes.

Methods

Participants

Patients with FM aged 20–60 years were enrolled consecutively from the Neurological Institute of Taipei Veterans General Hospital. All enrolled patients fulfilled the modified 2010 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for FM [2]. For data comparison, age- and sex-matched patients with CM and healthy controls were recruited. CM diagnoses met the International Classification of Headache Disorders-III criteria, beta version (code 1.3) [38]. Patients who met the criteria for both FM and CM were assigned to the FM group for simplicity because FM is a polysymptomatic syndrome and is often comorbid with migraine [1]. The control group did not have medical or family histories of FM or migraine. All participants denied having histories of systemic or major neuropsychiatric diseases. Participants who used any medication or hormone therapy on a daily basis were excluded. This study conformed to the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. The hospital’s institutional review board approved the study protocol (VGHTPE: IRB 2015-10-001BC), and all participants provided written informed consent. This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02747940).

Study Design

All patients with FM and CM completed a semistructured questionnaire for demographic information and FM and headache profiles during their first visit. Specifically, the FM profile included the distribution (widespread pain index) [2], intensity (0–10 on a numerical rating scale [NRS]), and duration (years) of bodily pain and accompanying somatic or psychiatric symptoms (symptom severity scale) [2]. In addition, the revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR) was administered to assess functional disability associated with FM. Notably, all participants were assessed for anxiety and depression by using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and the degree to which the participants appraised situations in their lives as stressful on the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS).

After enrollment, all patients were asked to maintain a diary to record their bodily pain (daily average severity on NRS, 0–10) or headache attacks (e.g., onset, intensity, duration, features, associated symptoms, and medication use). All participants underwent scheduled MEG recordings for the conditioned fear acquisition task (detailed in the subsequent section) and were instructed not to use any analgesics or other medications within 3 days before the recordings.

After MEG recording, all patients with FM were treated with 75 mg pregabalin. They maintained a diary of bodily pain severity for 3 months. The pregabalin dose was titrated up to 150 mg if patients reported no adverse effects and no improvement in bodily pain. At the 3-month follow-up, each patient with FM was allocated to the good or poor outcome group on the basis of their bodily pain severity (0–10, monthly averaged pain scores recorded in diaries) at baseline versus the third month of treatment. A good outcome was defined as a ≥ 30% reduction in bodily pain, whereas a reduction in pain of < 30% was regarded as a poor outcome.

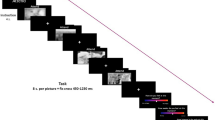

Conditioned Fear Acquisition Task

The acquisition phase of the fear conditioning paradigm used in the present study is illustrated in Fig. 1. The conditioned stimulus (CS) was a visual symbol of lightning (displayed for 200 ms), whereas the unconditioned (aversive) stimulus (UCS) was a moderately painful electrical shock (rated 5–6/10 on the NRS before the study) on the skin of the left lower leg delivered by a concentric electrode with a 0.2-ms constant-current square wave. Half of the CSs were immediately paired with UCS (paired CSs), and the other half were presented alone (unpaired CSs). Furthermore, to ensure participants’ vigilance during the recording, a visual symbol of the sun (displayed for 200 ms) was presented. All participants were asked to report the number of sun symbols at the end of each recording session. Participants who reported a difference of > 2 in the number of sun symbols presented were excluded from further analysis. In each recording session, paired CSs (probability, 45%), unpaired CSs (probability, 45%), and sun symbols (probability, 10%) were presented randomly, and the time interval between conditions was maintained at approximately 5.5–6.5 s.

MEG Recordings

The present study used a whole-scalp 306-channel neuromagnetometer (Vectorview; Elekta Neuromag, Helsinki, Finland) comprising 102 identical triple-sensor elements to record brain activity in all participants. Each sensor element consisted of one magnetometer and two orthogonal planar gradiometers. Four coils were placed on each participant’s scalp, and their positions on the head coordinate frame specified by the nasion and the two preauricular points were measured using a three-dimensional digitizer with Cartesian coordinates. Moreover, approximately 50 additional scalp points were digitized. These landmarks and points on the head allowed for further registration of MEG and MRI coordinate systems. One pair of electrodes was positioned and taped across each participant’s chest to capture synchronized electrocardiography with the MEG recording. Two electrodes were attached above and below one eye for electrooculography. During recordings, participants sat comfortably with the head supported against the helmet of the neuromagnetometer.

The signal digitization rate was 600 Hz. Moreover, the epoch length was 800 ms and included a prestimulus baseline 300 ms long, after which the CS onset occurred at 0 ms. At least 60 artifact-free epochs for both conditions (CS and UCS) were collected and subaveraged into first (epochs 1–30) and second (epochs 31–60) blocks. Epochs contaminated with prominent electrocardiogram signals, electrooculogram signals (> 300 μV), and MEG artifacts (> 3000 fT/cm) were automatically excluded from further analysis.

MEG Data Analysis

The present study analyzed only the 60 epochs of responses obtained from the UCSs to study the pain-anticipation fear process. Responses to paired CS stimuli were not analyzed because of interference from bottom-up nociceptive sensory processing and contamination of electrical artifacts from electrical stimulation.

During responses to UCSs, distributed source activities of MEG signals recorded from the entire head surface were estimated using depth-weighted minimum norm estimates (MNEs) [39,40,41], which accurately resolve source localizations even for the activities of deep generators [42, 43]. The neural dynamics of cortical and subcortical sources were calculated using a deep brain model that defines neural generators according to anatomical and electrophysiological priors for neocortex and subcortical structures [43]. The distributed source analysis of MEG data has two main steps.

First, the deep brain activity model was developed from the individual MRI-derived brain model to describe the signal pattern generated by a unit dipole, which realistically distributes current dipoles over the neocortex and subcortical structures [43]. Individual brain MRI images were acquired using a 3 T MR system (Siemens MAGNETOM Tim Trio) with the following parameters: repetition time, 9.4 ms; echo time, 4 ms; recording matrix, 256 × 256 pixels; field of view, 256 mm; and slice thickness, 1 mm. The shapes of surfaces separating the scalp, skull, and brain compartments were determined from T1-weighted anatomical MRI data by using FreeSurfer 5.0 (https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/), which was also used for the subcortical segmentation of a brain volume (Aseg atlas). This model explains how an electric current flowing in the brain is recorded at the sensor level with reasonable accuracy. Anatomical MRI, reconstructed cortical surface, and subcortical volume were subsequently co-registered with the corresponding MEG dataset.

Second, the inverse operator of MNE analysis was used to estimate the distribution of current sources that account for data recorded at the sensors. Data analysis for this part was performed using Brainstorm [44], which has been partly described in our previous studies [40, 41] and is summarized as follows: (a) the source orientations were constrained to be normal to surface regions (such as the cortex and hippocampus) but unconstrained to volume regions (such as the amygdala), (b) a depth weighting algorithm was used to compensate for any bias affecting the superficial source calculation, and (c) a regularization parameter of λ2 = 0.33 was used to minimize numerical instability, reduce the sensitivity of the MNE to noise, and obtain a spatially smoothed solution [42]. A noise covariance matrix was computed from 3-min empty-room recordings obtained before the tests.

The aforementioned MNE method resulted in distributed and dynamic brain activation maps that could be overlaid onto the reconstructed surface and volume for each participant. The regions of interest (ROIs), including the bilateral anterior insula, ACC, and amygdala, were selected from the Mindboggle and Aseg atlases. The activation dynamics of constrained cortical sources in the anterior insula and ACC were obtained from the averaged current density of each node within the area; in the amygdala, the norm of the vector resulting from unconstrained trihedral sources was computed at each volume grid. The mean time course of amygdala activity was then obtained by averaging all vector norms in the amygdala volume separately for the left and right amygdala. To increase the signal-to-noise ratio of the MNE maps, the time-resolved amplitude of each ROI was normalized to its baseline fluctuations, which were those measured from − 300 to − 100 ms. The z scores derived from this normalization represented the number of standard deviations with respect to baseline activity.

On the basis of the aforementioned computation of activation strength, this study obtained two MEG measures associated with the fear conditioning paradigm: (a) fear conditioning response strength, defined as the activation strength averaged from the first block of 30 epochs (hereafter, fear conditioning response) and (b) fear habituation, defined as the difference between the first and second blocks of 30 epochs (i.e., first-block activation strength − second-block activation strength). Fear habituation is a normal physiological phenomenon reflecting the suppression or habituation of the fear conditioning response in long-term stimulus repetition [18].

Statistical Analysis

Demographic information, clinical profiles, and MEG measures (strength of activation and degree of habituation) were compared between participant groups in an analysis of variance. A general linear model was used to examine the confounding effects of covariates (age, sex, and HADS) if necessary. To determine the effect of baseline activities on the calculation of z score amplitudes, the activation strength (without z transformation) at − 300 to − 100 ms was examined for the factor of participant groups. Pearson’s correlation was used to determine the clinical correlation of MEG measures in the FM and CM groups. Moreover, MEG measures were compared for the patients with FM who reported good and poor treatment outcomes. Finally, MEG measures that indicated group differences in the post hoc analysis were analyzed for their diagnostic (FM vs. CM vs. controls) and prognostic (good vs. poor FM treatment outcome) value in a logistic regression model (adjusted for age and sex) and a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Throughout the study, Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics and Clinical Profiles

This study included 132 participants (52 with FM, 50 with CM, and 30 controls). Age and sex did not differ among the three participant groups. However, differences were observed among groups in terms of anxiety (HADS-A), depression (HADS-D), and total HADS and PSS scores (all p < 0.01, Table 1). These scores were higher in the FM group than they were in the CM (all p < 0.05) and control (all p < 0.001) groups in the post hoc analysis.

All 52 patients with FM were treated with 75–150 mg of pregabalin, except for seven who reported intolerable adverse effects of the medication, mainly dizziness. Of the 45 patients with FM who received pregabalin treatment, 37 (82%) were successfully followed up after 3 months. Of them (n = 37), 22 were allocated to the good outcome group because they reported a > 30% reduction in their bodily pain severity; the remaining 15 were allocated to the poor outcome group.

Comparison of Fear Response Strength Between Participant Groups

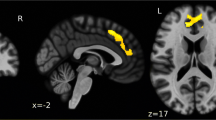

Dynamic brain activation during fear responses to UCSs is illustrated in Fig. 2 (healthy control #2 provided as an example). The visual lightning symbol elicited visual cortical activity that peaked at approximately 80 ms and subsequent activation of the inferior and lateral temporal and posterior parietal areas that peaked at 80–150 ms. In addition, fear conditioning activated the bilateral insula and amygdala, which peaked at 150–200 ms. Notably, no discernible activation was observed from the ACC.

Dynamic brain activation of fear responses in one participant (healthy control #2). Brain activation at − 300 to 500 ms was mapped onto the individual’s MRI images (two axial views and one sagittal view) to observe cortical and subcortical neural responses to pain-related fear. In response to UCSs, cortical activity peaked in the visual cortex at approximately 80 ms, followed by clear activation in the inferior and lateral temporal and posterior parietal areas at 80–150 ms. Subsequently, activation of the bilateral insula and amygdala peaked at 150–200 ms and ended at 200–250 ms. No clear activation was observed over the ACC in the corresponding time interval. The amplitudes of underlying neural activity were converted to z scores and color coded

Dynamic brain activation for the group-averaged fear responses of the three participant groups in the three ROIs are shown in Fig. 3. Clear responses were observed in the bilateral amygdala (Fig. 3a) and anterior insula (Fig. 3b) but not in the ACC (Fig. 3c). Because the control group exhibited clear activation in the left (152–195 ms) and right (142–208 ms) amygdala and the left (155–197 ms) and right (152–202 ms) anterior insula; thus, the time window for fear response extraction for further group comparison was determined to be 150–200 ms. Most activations of the amygdala and anterior insula observed in the FM and CM groups also peaked within this time window. Therefore, the average z score in this time window was regarded as the activation strength of the conditioned fear acquisition. Further comparisons of fear response strength did not reveal any group differences within this time window (FM vs. CM vs. controls, Fig. 3d, e) in the bilateral amygdala and anterior insula; similarly, no differences were observed between the groups in terms of activation strength (without z transformation) in the baseline period.

Grand-averaged dynamics of fear responses (first block) within the time window from − 300 to 500 ms in the bilateral a amygdala, b anterior insula, and c ACC obtained from healthy controls, patients with FM, and patients with CM. The gray shading represents the standard error of fear response activity. No discernible activation occurred in the ACC. Fear response strength was compared across participant groups in the bilateral d amygdala, e anterior insula, and f ACC. n.s. nonsignificant

Comparison of Fear Habituation Among Participant Groups

Fear habituation was computed as the difference between first- and second-block conditioning responses in the bilateral amygdala (Fig. 4a) and anterior insula (Fig. 4b). The degree of fear habituation differed among the three participant groups in the right amygdala [F(2, 129) = 10.6, p < 0.001] but not in the left amygdala [F(2, 129) = 2.1, p = 0.12]. In the post hoc analysis, fear habituation in the right amygdala was smaller in the patients with FM than in the patients with CM (p = 0.001) and the controls (p < 0.001). This group difference was further confirmed in a general linear model after adjustments for age, sex, anxiety, and depression (total HADS scores) [F(2, 129) = 6.1, p = 0.003]. Furthermore, fear habituation in the bilateral anterior insula differed among groups [right: F(2, 129) = 4.0, p = 0.020; left: F(2, 129) = 6.3, p = 0.002]. The post hoc analysis revealed a smaller habituation in the FM group than in the controls in the right (p = 0.022) and left (p = 0.002) anterior insula. However, no difference was observed after adjustments for anxiety and depression levels (all p > 0.05). No difference was observed between the CM and control groups in terms of fear habituation.

Grand-averaged dynamics of fear responses (blue, first block; red, second block) in the bilateral a amygdala and b anterior insula obtained from healthy controls (HC), patients with FM, and patients with CM. The reduction in fear response strength from the first to the second block was computed as fear habituation and compared between participant groups in the bilateral c amygdala and d anterior insula. *Corrected p < 0.05; **corrected p < 0.01; ***corrected p < 0.001

Comparison Between Outcome Groups in Patients With FM

At the 3-month follow-up, patients with FM who reported good (n = 22) and poor (n = 15) outcomes differed in terms of fear habituation in the left amygdala at baseline [good: 0.649 ± 0.302, poor: − 0.576 ± 0.41; F(1, 67) = 6.05, p = 0.019; Fig. 5]. No difference was observed between the two outcome groups (good vs. poor) for fear habituation in other regions or for fear response strength in any region (all p > 0.05). In addition, the clinical profiles of FM at baseline (number of tender points, widespread pain index, symptom severity scale score, and FIQR score) did not differ between these outcome groups.

Clinical Relevance

In patients with FM, fear response strength was negatively correlated with PSS scores in the bilateral amygdala (left: r = − 0.472, p < 0.001; right: r = − 0.413, p = 0.002) but not in the bilateral anterior insula (all p > 0.05). Moreover, fear response strength in the right anterior insula was associated with FIQR scores (r = 0.44, p = 0.002). In healthy controls and patients with CM, no such correlations were observed.

Fear habituation was not correlated with any score or clinical parameter at baseline in any of the participant groups (all p > 0.05). However, in the right amygdala, fear habituation could predict FM diagnosis in a logistic regression model after adjustments for age and sex [FM vs. control: odds ratio (OR), 2.67 (95% CI 1.58–4.51), p < 0.001; FM vs. non-FM (CM and controls): OR 1.94 (95% CI 1.38–2.73), p < 0.001]. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.765 for the FM group versus the controls (95% CI 0.663–0.868) and 0.704 for the FM groups versus the non-FM groups (95% CI 0.614–0.794), indicating good discrimination. In the left amygdala, a similar logistic region model confirmed the predictive value of fear habituation in FM prognosis [good vs. poor treatment outcome; OR 1.9 (95% CI 1.03–3.49), p = 0.04]. The AUC for left amygdala habituation in differentiating between good and poor outcomes of FM was 0.733 (95% CI 0.563–0.9), also indicating good discrimination (Fig. 6).

Discussion

This MEG study used a conditioned fear acquisition task to activate the bilateral amygdala and anterior insula in patients with FM, patients with CM, and healthy controls. Fear responses (in the first block) in these brain regions did not differ in strength among the participant groups. However, fear habituation (the reduction of fear response strength between the first and second blocks) in the right amygdala was reduced and predicted FM diagnosis in the FM group (vs. CM group and controls). Moreover, a reduced fear habituation in the left amygdala was predictive of poor response to pregabalin treatment in patients with FM. Patients with CM did not differ from controls in any measurement of fear response except for reduced habituation in the left insula, and this difference was nonsignificant after adjustments for anxiety and depression.

Consistent with previous neuroimaging studies [20,21,22,23,24,25], the present study demonstrated clear activation in the bilateral amygdala and anterior insula in response to the conditioned fear acquisition task. In the fear conditioning task, the CS induced the aversive properties of the UCS (painful electrical shock); even when subsequently presented alone, the CS elicited a fear response without actual afferent nociception. The activation of the amygdala and anterior insula peaked 150–200 ms after CS onset, indicating that fear response involves rapid and synchronized cortical and subcortical activation [45, 46]. The anterior cingulate has been clearly activated in the conditioned fear tasks of previous PET and MRI studies [21,22,23, 25, 26] but not in the present study. This difference may be attributable to methodological variation because the aforementioned PET and MRI studies have obtained fear responses by using aversive stimuli. By contrast, the amygdala activities analyzed in the present study without the elicitation of aversive stimuli. Furthermore, fear responses obtained in other studies without aversive stimuli have not resulted in anterior cingulate activation [20, 24]. Therefore, anterior cingulate activation may reflect attentional allocation in response to aversive stimuli [47], rather than a true neural substrate underpinning fear conditioning.

The first main finding of this study is the reduced fear habituation in the amygdala in patients with FM. Because fear habituation reflects the habituation of the fear response to fear conditioning [18], this finding indicates a maladaptation or overexpectation of pain-related fear. Clinically, this finding is consistent with behavioral (e.g., perceptual discrimination deficit) [48] and cognitive (e.g., catastrophizing) [49] changes associated with pain-related fear in patients with FM. Another notable finding in the amygdala is the negative correlation between fear response and perceived stress in patients with FM. Studies have suggested that an increased stress level can downregulate amygdala activation in fear or cognitive processing. A behavioral study in patients with chronic pain demonstrated a link between stress and impaired fear processing [50]. Moreover, an fMRI study revealed a negative correlation between anxiety level and amygdala activation during pain encoding in healthy participants [51]. The combination of downregulation and reduced habituation may explain the consistent fear response strength across the groups.

In addition to the amygdala, the anterior insula exhibited decreased fear habituation in the present study. However, this change seemed to be associated with the patients’ mental health because it did not reach significance after adjustments for depression and anxiety. In addition to mood, the anterior insula was associated with functional disability in FM, as indicated by the correlation between fear response and FIQR scores in this study. Moreover, our previous study that used resting-state MEG revealed an association between insula activity and functional disability in FM [39]. Thus, the aforementioned findings highlight a complex role of the anterior insula in chronic pain that involves not only affective factors [52] but also higher-order pain processing [53].

The second main finding of this study is the predictive value of amygdala fear habituation for the diagnosis and treatment outcomes of FM. Differentiation between FM and CM in pathophysiology is beyond the scope of the present study. Nevertheless, the diagnostic value of amygdala fear habituation in the present study implies that these two chronic pain conditions have different pathophysiologies, at least in terms of pain-related fear. Moreover, some findings from previous imaging studies have suggested that FM and CM are separate clinical entities. In gray matter volume studies, FM has been reported to significantly reduce gray matter volume in the amygdala [10] and exhibit an age-associated reduction in gray matter volume by 3.3 times compared with healthy controls [12], whereas gray matter volume exhibited structural plasticity that was nonlinearly linked to headache frequency in CM [54]. In functional connectivity studies, FM has been associated with reduced amygdala–ACC connectivity [11]; by contrast, increased connectivity between the amygdala and other pain-related regions has been observed in CM [55, 56]. Additional studies directly comparing patients with FM and CM (without comorbidity with each other) in terms of limbic structural and functional changes and thus elucidating the reasons of the discrepancies in fear habituation are warranted.

Amygdala fear habituation predicted pregabalin treatment outcomes in patients with FM. Previous studies indicating an association between the amygdala and sensory areas [55, 56] have provided a theoretical basis for the intermediation of amygdala activity on bodily pain in FM. Some interventional studies have further demonstrated the modulatory effect of pregabalin on amygdala activity. In a pharmaco-fMRI study [57], left amygdala activation when emotional stimuli were anticipated decreased in healthy participants with pregabalin administration. In an animal study, pregabalin downregulated the activity of the amygdala and related corticosubcortical networks after a fear-inducing stimulus, resulting in an anxiolytic effect [58]. Moreover, duloxetine, another standard treatment for FM, had a modulatory effect on the bottom-up processing of biologically salient information in extended amygdala circuitry in an fMRI study of healthy participants [59]. The amygdala may be a pharmacological target for standard FM treatments such as pregabalin and duloxetin; hence, a link between amygdala fear habituation and pregabalin treatment outcomes was established in the present study. In the era of precision medicine, studies must elucidate whether amygdala fear habituation can be used as a brain signature for pregabalin efficacy in patients with FM.

This study has limitations. First, painful electric stimulation was delivered to the lower leg of the participants rather than around the head (to mimic headache) to prevent unwanted artifacts during MEG recording. The different pain experiences and pain distributions between patients with FM and those with CM may partially account for the difference in their fear response patterns. Second, the present study design could not elucidate causal relationships between amygdala fear responses and the clinical parameters. Additional longitudinal studies would be particularly valuable to elucidate these relationships. Third, depression is a common comorbidity of chronic pain that may alter amygdala activity [9]. Thus, this study excluded patients who had major depression and adjusted the severity of depressive symptoms in the statistical analyses of patients with FM and CM. Moreover, we did not enroll patients with major depression as an isolated disease control group because of unwanted confounding due to antidepressant use. Finally, there are different types of fear-conditioned behavior that are mediated by the nuclei within the amygdala [60]. This study focused on pain-related fear; therefore, whether the aforementioned changes can be generalized to other types of fear remains unknown.

Conclusions

Here, patients with FM were characterized by reduced response habituation to pain-related fear in the amygdala. This abnormal neuromodulation in the amygdala was absent in patients with CM and reduced in the FM subgroup with good treatment outcomes. Amygdala fear response may be a brain signature of FM that can predict FM diagnosis and treatment outcomes; however, longitudinal studies with large patient samples is required for further confirmation these results.

References

Hauser W, Ablin J, Fitzcharles MA, Littlejohn G, Luciano JV, Usui C, et al. Fibromyalgia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15022.

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Hauser W, Katz RS, et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(6):1113–22.

Sluka KA, Clauw DJ. Neurobiology of fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain. Neuroscience. 2016;338:114–29.

Meulders A, Jans A, Vlaeyen JW. Differences in pain-related fear acquisition and generalization: an experimental study comparing patients with fibromyalgia and healthy controls. Pain. 2015;156(1):108–22.

Meulders A, Meulders M, Stouten I, De Bie J, Vlaeyen JW. Extinction of fear generalization: a comparison between fibromyalgia patients and healthy control participants. J Pain. 2017;18(1):79–95.

Jenewein J, Moergeli H, Sprott H, Honegger D, Brunner L, Ettlin D, et al. Fear-learning deficits in subjects with fibromyalgia syndrome? Eur J Pain. 2013;17(9):1374–84.

Turk DC, Wilson HD. Fear of pain as a prognostic factor in chronic pain: conceptual models, assessment, and treatment implications. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14(2):88–95.

Schmidt-Wilcke T, Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: from pathophysiology to therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(9):518–27.

Dalgleish T. The emotional brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(7):583–9.

Burgmer M, Gaubitz M, Konrad C, Wrenger M, Hilgart S, Heuft G, et al. Decreased gray matter volumes in the cingulo-frontal cortex and the amygdala in patients with fibromyalgia. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(5):566–73.

Jensen KB, Loitoile R, Kosek E, Petzke F, Carville S, Fransson P, et al. Patients with fibromyalgia display less functional connectivity in the brain's pain inhibitory network. Mol Pain. 2012;8:32.

Kuchinad A, Schweinhardt P, Seminowicz DA, Wood PB, Chizh BA, Bushnell MC. Accelerated brain gray matter loss in fibromyalgia patients: premature aging of the brain? J Neurosci. 2007;27(15):4004–7.

Cagnie B, Coppieters I, Denecker S, Six J, Danneels L, Meeus M. Central sensitization in fibromyalgia? A systematic review on structural and functional brain MRI. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(1):68–75.

Williams DA, Gracely RH. Biology and therapy of fibromyalgia. Functional magnetic resonance imaging findings in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(6):224.

Lutz J, Jager L, de Quervain D, Krauseneck T, Padberg F, Wichnalek M, et al. White and gray matter abnormalities in the brain of patients with fibromyalgia: a diffusion-tensor and volumetric imaging study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(12):3960–9.

Pujol J, Lopez-Sola M, Ortiz H, Vilanova JC, Harrison BJ, Yucel M, et al. Mapping brain response to pain in fibromyalgia patients using temporal analysis of FMRI. PLoS One. 2009;4(4):e5224.

Harris RE, Napadow V, Huggins JP, Pauer L, Kim J, Hampson J, et al. Pregabalin rectifies aberrant brain chemistry, connectivity, and functional response in chronic pain patients. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(6):1453–64.

Maren S. Neurobiology of Pavlovian fear conditioning. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:897–931.

Zaman J, Vlaeyen JW, Van Oudenhove L, Wiech K, Van Diest I. Associative fear learning and perceptual discrimination: a perceptual pathway in the development of chronic pain. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;51:118–25.

LaBar KS, Gatenby JC, Gore JC, LeDoux JE, Phelps EA. Human amygdala activation during conditioned fear acquisition and extinction: a mixed-trial fMRI study. Neuron. 1998;20(5):937–45.

Morris JS, Dolan RJ. Dissociable amygdala and orbitofrontal responses during reversal fear conditioning. Neuroimage. 2004;22(1):372–80.

Buchel C, Dolan RJ, Armony JL, Friston KJ. Amygdala-hippocampal involvement in human aversive trace conditioning revealed through event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 1999;19(24):10869–76.

Jensen J, McIntosh AR, Crawley AP, Mikulis DJ, Remington G, Kapur S. Direct activation of the ventral striatum in anticipation of aversive stimuli. Neuron. 2003;40(6):1251–7.

Ploghaus A, Tracey I, Gati JS, Clare S, Menon RS, Matthews PM, et al. Dissociating pain from its anticipation in the human brain. Science. 1999;284(5422):1979–81.

Schiller D, Levy I, Niv Y, LeDoux JE, Phelps EA. From fear to safety and back: reversal of fear in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2008;28(45):11517–25.

Blaxton TA, Zeffiro TA, Gabrieli JD, Bookheimer SY, Carrillo MC, Theodore WH, et al. Functional mapping of human learning: a positron emission tomography activation study of eyeblink conditioning. J Neurosci. 1996;16(12):4032–40.

Ossipov MH, Dussor GO, Porreca F. Central modulation of pain. J Clin Investig. 2010;120(11):3779–877.

Smallwood RF, Laird AR, Ramage AE, Parkinson AL, Lewis J, Clauw DJ, et al. Structural brain anomalies and chronic pain: a quantitative meta-analysis of gray matter volume. J Pain. 2013;14(7):663–75.

Chen WT, Chou KH, Lee PL, Hsiao FJ, Niddam DM, Lai KL, et al. Comparison of gray matter volume between migraine and "strict-criteria" tension-type headache. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):4.

Giesecke T, Gracely RH, Williams DA, Geisser ME, Petzke FW, Clauw DJ. The relationship between depression, clinical pain, and experimental pain in a chronic pain cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(5):1577–84.

de Tommaso M, Federici A, Santostasi R, Calabrese R, Vecchio E, Lapadula G, et al. Laser-evoked potentials habituation in fibromyalgia. J Pain. 2011;12(1):116–24.

Montoya P, Sitges C, Garcia-Herrera M, Rodriguez-Cotes A, Izquierdo R, Truyols M, et al. Reduced brain habituation to somatosensory stimulation in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(6):1995–2003.

Smith BW, Tooley EM, Montague EQ, Robinson AE, Cosper CJ, Mullins PG. Habituation and sensitization to heat and cold pain in women with fibromyalgia and healthy controls. Pain. 2008;140(3):420–8.

Hämäläinen M, Hari R, Ilmoniemi RJ, Knuutila J, Lounasmaa OV. Magnetoencephalography: theory, instrumentation, and applications to noninvasive studies of the working human brain. Rev Mod Phys. 1993;65(2):413.

Sarchielli P, Mancini ML, Floridi A, Coppola F, Rossi C, Nardi K, et al. Increased levels of neurotrophins are not specific for chronic migraine: evidence from primary fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2007;8(9):737–45.

Valenca MM, Medeiros FL, Martins HA, Massaud RM, Peres MF. Neuroendocrine dysfunction in fibromyalgia and migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009;13(5):358–64.

Vij B, Whipple MO, Tepper SJ, Mohabbat AB, Stillman M, Vincent A. Frequency of migraine headaches in patients with fibromyalgia. Headache. 2015;55(6):860–5.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211.

Hsiao FJ, Wang SJ, Lin YY, Fuh JL, Ko YC, Wang PN, et al. Altered insula-default mode network connectivity in fibromyalgia: a resting-state magnetoencephalographic study. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):89.

Hsiao FJ, Wang SJ, Lin YY, Fuh JL, Ko YC, Wang PN, et al. Somatosensory gating is altered and associated with migraine chronification: a magnetoencephalographic study. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(4):744–53.

Chen WT, Hsiao FJ, Ko YC, Liu HY, Wang PN, Fuh JL, et al. Comparison of somatosensory cortex excitability between migraine and "strict-criteria" tension-type headache: a magnetoencephalographic study. Pain. 2018;159(4):793–803.

Hamalainen MS, Ilmoniemi RJ. Interpreting magnetic fields of the brain: minimum norm estimates. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1994;32(1):35–42.

Attal Y, Schwartz D. Assessment of subcortical source localization using deep brain activity imaging model with minimum norm operators: a MEG study. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59856.

Tadel F, Baillet S, Mosher JC, Pantazis D, Leahy RM. Brainstorm: a user-friendly application for MEG/EEG analysis. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2011;2011:879716.

Sato W, Kochiyama T, Uono S, Yoshikawa S, Toichi M. Direction of amygdala-neocortex interaction during dynamic facial expression processing. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27(3):1878–90.

Balderston NL, Schultz DH, Baillet S, Helmstetter FJ. Rapid amygdala responses during trace fear conditioning without awareness. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96803.

Bush G, Whalen PJ, Rosen BR, Jenike MA, McInerney SC, Rauch SL. The Counting Stroop: an interference task specialized for functional neuroimaging–validation study with functional MRI. Hum Brain Mapp. 1998;6(4):270–82.

Laufer O, Paz R. Monetary loss alters perceptual thresholds and compromises future decisions via amygdala and prefrontal networks. J Neurosci. 2012;32(18):6304–11.

Harvie DS, Moseley GL, Hillier SL, Meulders A. Classical conditioning differences associated with chronic pain: a systematic review. J Pain. 2017;18(8):889–98.

Elsenbruch S, Wolf OT. Could stress contribute to pain-related fear in chronic pain? Front Behav Neurosci. 2015;9:340.

Tseng MT, Kong Y, Eippert F, Tracey I. Determining the neural substrate for encoding a memory of human pain and the influence of anxiety. J Neurosci. 2017;37(49):11806–17.

Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(8):655–66.

Williams M, Ng M, Ashworth M. What is the incidence of inadvertent hypothermia in elderly hip fracture patients and is this associated with increased readmissions and mortality? J Orthop. 2018;15(2):624–9.

Liu HY, Chou KH, Lee PL, Fuh JL, Niddam DM, Lai KL, et al. Hippocampus and amygdala volume in relation to migraine frequency and prognosis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(14):1329–36.

Hadjikhani N, Ward N, Boshyan J, Napadow V, Maeda Y, Truini A, et al. The missing link: enhanced functional connectivity between amygdala and visceroceptive cortex in migraine. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(15):1264–8.

Schwedt TJ, Schlaggar BL, Mar S, Nolan T, Coalson RS, Nardos B, et al. Atypical resting-state functional connectivity of affective pain regions in chronic migraine. Headache. 2013;53(5):737–51.

Aupperle RL, Ravindran L, Tankersley D, Flagan T, Stein NR, Simmons AN, et al. Pregabalin influences insula and amygdala activation during anticipation of emotional images. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(7):1466–77.

Wang Z, Pang RD, Hernandez M, Ocampo MA, Holschneider DP. Anxiolytic-like effect of pregabalin on unconditioned fear in the rat: an autoradiographic brain perfusion mapping and functional connectivity study. Neuroimage. 2012;59(4):4168–88.

van Marle HJ, Tendolkar I, Urner M, Verkes RJ, Fernandez G, van Wingen G. Subchronic duloxetine administration alters the extended amygdala circuitry in healthy individuals. Neuroimage. 2011;55(2):825–31.

Killcross S, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Different types of fear-conditioned behaviour mediated by separate nuclei within amygdala. Nature. 1997;388(6640):377–80.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients, study participants, and associated staff for their contributions and participation.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 107-2314-B-075-015-MY2-2 to WT Chen, 108-2321-B-010-001 and 108-2321-B-010-014-MY2 to SJ Wang, 107-2221-E-010-007, 108-2221-E-010-004 to FJ Hsiao), Taipei-Veterans General Hospital (V108C-129, V107C-091 to WT Chen), Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation (CI-109-1 to FJ Hsiao), Brain Research Center, National Yang-Ming University from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Shuu-Jiun Wang has served on the advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo, Taiwan Pfizer, and Taiwan Novartis. He has received honoraria as a moderator from Allergan, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Bayer, and Eisai. Other authors Fu-Jung Hsiao, Wei-Ta Chen, Yu-Chieh Ko, Hung-Yu Liu, Yen-Feng Wang, Shih-Pin Chen, Kuan-Lin Lai, Hsiao-Yi Lin and Gianluca Coppola have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The hospital’s institutional review board approved the study protocol (VGHTPE: IRB 2015-10-001BC), and each participant provided written informed consent. This study was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT02747940) and conformed to the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hsiao, FJ., Chen, WT., Ko, YC. et al. Neuromagnetic Amygdala Response to Pain-Related Fear as a Brain Signature of Fibromyalgia. Pain Ther 9, 765–781 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00206-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-020-00206-z