Abstract

Introduction

Adolescents’ pain experiences are complex and multidimensional, and evaluating pain only from a sensory and affective point of view may be in many instances limiting and inadequate; this is the reason why it is of paramount importance to identify the tools which can better assess the pain experienced by young patients. A person-oriented approach is highly encouraged, as it may better investigate the cognitive and behavioral development typical of this age group. The aim of this review paper is to describe the available tools which are able to adequately assess pain intensity in adolescents, in particular those validated in Italian.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review using four databases: CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMed and Cochrane, and selected all the articles published between January 1970 and November 2017. We selected all the papers reporting the validation process of pain assessment tools specifically tailored for adolescent patients (age range 10–18 years) and based on psychometric and linguistic parameters, and focused especially on the tools available in Italian and able to measure acute and chronic pain.

Results

The results of our investigation have revealed the existence of 40 eligible tools, 17 of which are monodimensional and the remaining 23 multidimensional, more specifically tailored to assess both acute and chronic pain. Some of the instruments (26) were self-reports while others were classified as behavioral (13) and/or mixed. Only one tool turned out to be suitable for fragile adolescents, while six adopted a person-oriented approach that better emphasized the cognitive and behavioral process typical of the adolescent population. None of them has ever been validated in Italian.

Conclusion

Valid and reliable psychometric tools specifically organized to provide a cultural and linguistic evaluation of the patient are indeed the most recommended instruments to assess the intensity of the pain experienced by the patient, as they may provide useful information to implement a health policy aimed at identifying the best assistance programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (2014) identifies adolescence as the period in human growth and development that occurs after childhood and before adulthood, from ages 10 to 19. It represents one of the critical transitions in the life span and is characterized by a tremendous pace in growth and by important biological changes. Although the biological determinants of adolescence are fairly universal, the duration and defining characteristics of this period may vary across time, cultures, and socioeconomic situations [1].

During each growing phase in a child’s life, pain is experienced in different ways, according to the child’s age and his evolutionary, psychological and biological development [2]. The child’s communicative capacity, comprehension skills and past painful experiences may affect the way of perceiving pain throughout his whole life. Many children and adolescents with repeated acute episodes of nociceptive pain develop chronic pain that increases the risk of pain, as well as physical and psychiatric disorders in adulthood [3].

Patients aged 0–18 make up about 22% of admissions to emergency departments in the USA; among the symptoms for seeking hospital care, reporting of pain [4] seems to be quite common, and the prevalence of self-reporting increases proportionally with age. A painful event may vary from the typical everyday pain experienced by a child (i.e., bumps and bruises) [5] to more serious causes that require medical care or admission to hospital [6]. Pain is a subjective and multidimensional experience [7], which needs to be carefully assessed when it occurs in adolescents, as patients falling within this particular age group tend to minimize or even to deny pain to their parents and friends [8]. The cognitive and psychological development of adolescents gives pain a multidimensional perspective not limited to the sensory experience; sometimes the cause of pain itself may influence the way people individually respond to it [9]. Pain in some adolescents upsets their daily life, in that the intense fear of pain and disability emerge as particularly important, also influencing the lives of their parents that report significant distress and changes in their roles [10].

In addition, health professionals may be influenced by false and outdated beliefs which lead them to misinterpret the way pediatric patients feel pain, influencing therefore their capacity to properly assess its real intensity [11]. Misinterpreting results and underestimating pain may lead to an inadequate management of both acute and chronic pain [12]. As highlighted in a recent Italian survey, we observed that Italian nurses lack an adequate preparation to properly assess pain, which may account for the general low prescriptive appropriateness [13].

Therefore, the health personnel dealing with patients belonging to this specific age group must be aware of their particular bio-psychological characteristics and should find the most suitable assessment tools normally difficult to apply in clinical practice [14]. Of note, a lack of pain education in nursing and medical schools is the major cause for underestimating chronic pain in adolescents, especially from a diagnostic point of view [15], as chronic pain is normally attributed and identified only with older patients. It is estimated that about 25% of pediatric patients suffer from chronic pain [16] and these findings confirm that, differently than expected, it is a common complaint in childhood and adolescence, the most affected age group represented by adolescents between 12 and 15 years of age [17].

Chronic and acute pain assessment tools to measure the intensity of pain in adolescent patients are countless and may be classified as self-reports, behavioral observations or physiologic measures.

Assessments that use multiple measures (behavioral and physiologic) and assess different aspects of the pain experience (i.e., intensity, location, pattern, context, and meaning) may result in more accurate appraisals of pediatric pain experiences [8].

Self-reporting methods are considered the gold standard for the assessment of pain, both in adolescents and younger patients [11], and may use verbal and non-verbal tools; however, only children who have attained a certain degree of cognitive ability are able to provide information this way. The capacity to self-report increases proportionally to the age of the patient and may be further enriched by life experiences typical of patients classified as adolescents [18]. Preverbal patients or those with serious cognitive impairments cannot communicate their pain in words [19]. In the absence of self-reporting, behavioral and physiologic parameters have to be used to infer pain. Behavioral indicators of pain include facial expressions, weeping, gross motor movements, changes in behavioral state and patterns [20].

In some instances, behavioral and self-report tools may be associated to physiological scales that may measure the pediatric patient’s response to stressful events by using parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure and sweating of the hands [8]. The available literature reports the existence of multidimensional scales, which simultaneously use self-report, behavioral and physiological variables to assess frail pediatric patients [21].

Given the high number of pain assessment tools reported in literature that can be specifically applied to adolescent patients, the aim of this study was to summarize and describe their most remarkable psychometric and linguistic features. This may help health practitioners who need to be advised on how to apply such tools in clinical practice. Particular attention was paid to all the tools validated in Italian, which are therefore fit to be used in national clinical settings.

Methods

Research Strategies

This systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines, using four databases: CINAHL Plus with full text, PsycINFO, PubMed and Cochrane. Information was retrieved by using the following key words: pain measurement, adolescent, pain scale. A search string that could efficiently retrieve studies on (adolescent) AND (pain OR analgesia) AND (scale OR assessment) was developed and all the articles published from January 1970 to November 2017 were selected. Secondly, the results were further filtered by including patients between 10 and 18 years of age. A more accurate selection was possible thanks to the snowballing sampling strategy, which implied the careful reading of all the eligible articles, checking if the included articles cited any other relevant article that respect our inclusion criteria. We retrieved those articles and continued this process until the absence of other relevant articles. The snowballing strategy allowed us to include the pain assessment tools which had been missed by the electronic database research strategy. The same articles selected by two or more online database were included among the results only once.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We selected all the articles reporting the validation process of pain assessment tools specifically tailored for adolescent patients (age range 10–18 years) and based on psychometric and linguistic parameters. We mainly focused on the tools available in Italian and able to measure acute and chronic pain. Our revision excluded all those articles written in languages different from English and Italian, as well as those centered mostly on evaluating the best tools to be applied when deciding on a pharmacological/non-pharmacological or surgical treatment.

Analysis of the Psychometric Characteristics

Pain assessment is a multidimensional observational assessment of a patient’s experience of pain, including its characteristics and the impact it may have on daily life activities [22].

We needed valid and reliable tools to make a rigid and accurate evaluation of a parameter that could be strongly influenced by the subjective way of perceiving pain. By reliability we referred to the stability of the tool, meaning it was able to provide equivalent results after repeated administrations and regardless of the interviewer. The soundness of the tool could be demonstrated in various ways, i.e., by confirming its validity and reliability [23].

A certain tool may be considered reliable and valid if applied on a specific population, while it may be totally inadequate for another set of patients affected by different clinical conditions [7].

Data Retrieval

All the articles retrieved by the different data banks were selected according to their title and abstract and, if pertinent to our study, the full text was analyzed. During the whole selection phase, the articles were evaluated according to the inclusion/exclusion criteria previously described.

Encoding the Psychometric Characteristics

Validity (content, criterion and construct) and reliability (stability, internal consistency and equivalence) are essential to test the psychometric characteristics of pain assessment tools and are useful to subsidize the selection of trustworthy instruments that may ensure the quality of the results of studies [23]. The selected articles were then classified according to the model adopted by Law et al. [24] and already presented in a secondary study [8]. A Likert scale was used to confer different quality levels to each evaluated tool that was classified as being “excellent, satisfactory or mediocre”. A tool was considered “excellent” when it could be applied in more than two well-performed studies, “satisfactory” if used in not more than two well-performed studies and “mediocre” if applied in unsatisfactory studies or not applied at all. A researcher who wishes to use a pain assessment tool in a study or in a clinical setting usually tends to adopt the instrument that mostly satisfies the required psychometric characteristics, although he/she also refers to those studies in which that same tool has been frequently adopted.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

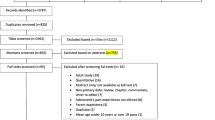

The preliminary research retrieved 1583 articles from public data banks such as PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Cochrane. Selection criteria are reported in Fig. 1. We identified 61 eligible papers which were in compliance with our inclusion/exclusion criteria. With the snowballing strategy we identified 26 more suitable articles; at the end of the review process, we were able to identify 40 tools normally used to assess pain in adolescent patients.

By analyzing the age range to which each tool could be applied, only six instruments (Table 1): Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool (APPT) [25], Bath Adolescent Pain questionnaire (BAPQ) [22], Pain-related Problem List (PPL) [26], Pediatric Pain Questionnaire (PPQ) [27], Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire—Adolescent Version (PSOCQ-A) [28], and Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire—Parent Version (PSOCQ-P) [28] turned out to be suitable for assessing pain in adolescents between 10 and 18 years of age. The characteristics and strength/weakness points of the tools specifically intended for adolescents are summarized in Table 2. We also managed to identify 29 tools (Table 3) which could be applied not only to adolescents but to a wider population set (0 years to adult age). Further five tools (Table 4): Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS) [29], Poker Chip Tool (HPCT) [30], Comprehensive Pain Evaluation Questionnaire Modified (CPEQ-M) [31], Face Legs, Activities, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) [32], and Observational Scale of Behavioral Distress (OSBD) [33] were instead specific for a pre-adolescent population (< 10 years), but could also be used in older patients or in mentally impaired adolescents unable to verbally assess their pain.

Analyzing the dimension of the pain scales, our literature review identified 23 multidimensional scales useful to assess pain intensity in youth. The Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ) [22], for instance, evaluates social, physical and family functioning. The Child Self-Efficacy Scale (SEQ-C) [34] evaluates the adolescent’s capacity to set up friendly ties, to self-assess his school progress, to perform simple housework tasks, to take care of himself and to autonomously do his homework. The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) [35] is a tool specifically tailored to evaluate the patient’s way to manage his emotions affections. The Pain Experience Questionnaire—child version (PEQ-C) [36] monitors emotional discomfort and social support. The Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire (adolescent version; PSOCQ-A) [28] measures the youth actions and expectations, while his emotions and affections are evaluated by using the Pediatric Pain Assessment Tool (PPAT) [37]. Finally, the Pediatric Pain Questionnaire (PPQ) [27] takes into account several factors, from social support to the capacity to carry out problem-solving strategies, from the search of physical and mental distraction to externalization/internalization. Our research also found 17 monodimensional assessment tools which are mostly focused on measuring the intensity of the experienced pain.

Analyzing the type of pain, we found 11 scales for the assessment of chronic pain applicable to patients ranging from 4 to 20 years of age, although only 5 turned out to be adolescent-specific. Acute pain is normally assessed with 17 scales. Five instruments are recognized as being suitable for assessing chronic and recurrent pain, and lastly seven assessment scales did not clearly specify to what kind of pain they could be favorably applied. Classifying the pain scales about the type of measurement we retrieved 13 behavioral assessment tools and 26 self-report tools. The only mixed tool that could be successfully applied to fragile children was the Questionnaire on Pain caused by Spasticity (QPS) [38]. Table 5 reports the psychometric properties rated using the criteria described by Law et al. [24].

Our review highlighted the lack of pain assessment tools validated in Italian and suitable for adolescent patients.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to summarize and describe psychometric and linguistic features of tool assessment for pain in adolescent patients. Adolescence is the period in human growth and development that occurs before and is different from adulthood [1], a significant psychosocial benchmark characterized by rapid growth and a unique way of experiencing pain, very likely dependent on the patients biological/psychological development, their comprehension and communicative skills and on any painful experience they may have experienced during their childhood [2]. The first step to take in order to avoid any possible underestimation of the importance of properly treating pediatric pain [39] is to use necessary and reliable tools in different clinical settings. Our review has obtained several pain assessment tools applicable to the adolescent population. Although pain assessment prefers to adopt a person-oriented approach, which better highlights the cognitive development and the behavioral attitude typical of this age group [40], our review has recognized only 6 tools that can be used on patients of an age ranging from 10 to 18 years (Table 1). Another 29 instruments, specifically reported in Table 3, can be more widely applied to a wider population of patients aged 0–18 years. Keep in mind that each assessment process has to take into account the characteristics and personal features of each evaluated subject so as to deliver a more accurate and personalized evaluation [41]. Assessment tools specifically intended for children between 0 and 7 years of age (Table 4), who in most instances are unable or only partially capable to verbally express the intensity of their pain, may also be applied to cognitively impaired pediatric patients, such as children affected by Down Syndrome, who find it very difficult to express the precise localization and intensity of their suffering [42]. These more vulnerable subjects may benefit from using body diagrams to easily identify the exact location of their pain [43]. It is important not to compromise the observers’ judgment and to avoid doing this we need to make a global assessment of the patient from a clinical point of view. It is necessary to identify the presence of pre-existing clinical conditions, comorbidity and disability, as well as consider the age, education status, communicative skills, cognitive process, ethnic/biologic/cultural aspects and any previous pain experiences [44]. This review has highlighted how multidimensional tools have outnumbered monodimensional ones, which means that particular attention has been paid to the overall assessment of the adolescent suffering from pain and the impact this has on the quality of life of the young patient. Health no longer means merely “absence of illness” but extends to a wider concept of psycho-social welfare. This new way of evaluating the patient’s symptomatology requires the use of more and more accurate tools capable of assessing the intensity of pain by analyzing additional pain-related information. Such tools are shaped on multidimensional instruments specifically applicable to the adolescent population [45]. This paper has considered 23 multidimensional pain assessment scales used to measure pain in adolescent patients; all the tools suitable for patients belonging to this age group proved to be multidimensional, meaning that pain is not limited to a sensory experience, but implies several other aspects [9].

Monodimensional scales, on the contrary, are certainly more suitable to highlight one of the most important aspects of discomfort, that is the severity of pain, defined as the fifth vital sign. The degree of severity has to be constantly monitored [46], but cannot be the only parameter used to confirm the patient’s distress [16]. Although all vital parameters may be affected by the presence of pain [47], it has been observed that significant variations do not necessarily occur only during painful procedures. Vital signs are easily accessible but represent only one of the aspects that nurses and healthcare operators should take into account when making a global pain assessment. Only five scales were suitable to measure the severity of pain in adolescent patients: BAPQ, PPQ, PPL, PSOCQ-A, and PSOCQ-P. Chronic pain is a health issue which normally characterizes the adult and geriatric population, where 50% of the subjects > 65 years of age show multiple chronic morbidity [48]; however, no age group is to be considered immune to this kind of suffering and the adolescent population seems to be one of the selected targets [16]. A study from a few years back [6] demonstrated that pediatric patients suffering from chronic pain reached a percentage of 25%. As in adults, chronic pain in younger patients is also a multidimensional condition affecting several aspects of the child’s life: social relations, education, ability to perform physical activities, and limitations which may lead to social isolation [49]. In particular, pain assessment in this specific category of patients needs to use tools capable of investigating all the parameters typical of patients belonging to this age group. The adolescent years are characterized by the maturation of emotional and cognitive abilities that provide the developing individual with capacities needed for independent functioning during adulthood, and this process affects all the patterns of logic and social significance [8].

As a matter of fact, some of the available tools enable making a comprehensive evaluation. Pain assessment includes a series of sequential steps that measure the degree of discomfort experienced by the patient; however, in assessing chronic pain, this process should also evaluate to what extent pain impacts the life of the young patient, not only from a biological point of view but also in the social and psychological spheres [16]. Pain assessment has to take into account all the changes that seriously impact the patient’s quality of life and evaluate the outcome of the administered treatments. In some instances, the reassessment process is included in the tool, as in the case of Chronic Pain Grading (CPG), Pain indicator for communicatively impaired children (PICIC), Pediatric Pain Profile (PPP), Questionnaire on Pain caused by Spasticity (QPS), which consider the systematic re-evaluation of the pain after a given time interval. The accuracy of a pain assessment tool is also given by its validation, which takes into account the linguistic and cultural characteristics of a specific territory and population. Most of the tools presently in use are published in English. Our investigation was able to identify only 10 instruments validated in Italian, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS), Face Legs Activities Cry Consolability (FLACC), Face Pain Scale (FPS), Face Pain Scale Revised (FPS-R), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Non-communicating Children’s Pain Checklist Postoperative version (NCCPC-PV), Non-communicating Children’s Pain Checklist Revised (NCCPC-R), Numeric Rate Scale (NRS), OUCHER, and Pain Catastrophizing Scale for Children (PCS-C), which were not applicable to the adolescent population. Pain assessment tools validated in Italian may exist, although our research did not provide us with any of them. Validation of these available instruments may presently be ongoing or in press. According to the Italian National Institute for Statistics, there are about 416,7000 adolescents in Italy, totaling 14.58% of the entire population [50]; however, the epidemiology of chronic pain in this population still remains unclear. Existing literature reports that 25% of children and adolescents suffer from chronic pain [6]. The lack of pain assessment tools suitable for adolescents may have serious implications from a clinical, ethic and juridical perspective. Pain is a public health concern which is often under-reported, underestimated and untreated in a population set that will soon reach adulthood. It is important to remember that perception of pain is influenced by the level of education of the patient, but the determinants of health also include the social, economic and physical environments, as well as the person’s individual characteristics, beliefs and behaviors. All these factors inevitably influence the acceptance and outcome of medical treatment. Linguistic validation is an essential step to make a tool reliable and applicable in the cultural setting where it is used [29]. As of January 1, 2015, in Italy 1,130,946 foreign children between 0 and 18 years were regularly registered, and of these 427,014 were adolescents, all from 191 different nations, the 10 most representative being Romania, Albania, Morocco, Ukraine, the People’s Republic of China, Philippines, Moldova, India, Bangladesh and Peru. A total of 67.4% of the adolescent population in Italy is represented by these ethnic groups [50]. Although born in Italy, they are inevitably influenced by the cultural background and linguistic traditions of their parents’ native country. Therefore, pain assessment tools also have to take into account and include these important cultural aspects [51]. Linguistic validation represents a step towards a reliable applicability of the tool to patients of a given nationality; however, the different ethnic characteristics may also help to reach a more accurate assessment of pain. Our review has retrieved two “faces” of pain scales (African-American Oucher Scale and Oucher) for self-assessing the severity of pain (smiling face, unhappy face) experienced by children of different ethnic groups: Afro-American, Caucasian, Hispanic, Asiatic, and First Nations peoples (Native Americans). Obtaining an accurate self-assessment of pain is vital to gauging baseline discomfort and response to therapy; children have to be able to identify themselves in the image they see and this is why pictures representing the various ethnic groups should be used. The use of male figures alone is discouraged even if stylized, as they may prevent girls from identifying themselves with the shown picture [52]. Picture pain scales that use drawings of both sexes (boys/girls) were found only in the versions specifically validated for Asiatic and the First Nations peoples.

Most of the tools which emerged from our survey (no. 26) are of the self-report type, meaning that attention is specifically focused on the importance of recognizing the subjective experience of pain [11]. The importance of subjectivity is stressed in some tools more than in others, as in the case of Individualized Numerical Rating Scale (INRS) [53], a unique and personalized pain assessment instrument tailored for a single patient. The Pediatric Pain Profile (PPP), on the contrary, is a rating scale for assessing pain in children with the help of their parents, who can understand how their child is feeling (well or unwell), thus reducing the risk of underestimating the intensity of their pain [54]. When we have to evaluate patients verbally unable to communicate, there is the need to use behavioral pain assessment tools. We found 13 tools of this kind, which measure the intensity of pain by observing the patient’s posture. As these are monodimensional tools, they are limited to measuring only the sensory aspect of pain, rather than assessing the distressful experience in its whole complexity [9], which may generate potential measurement biases if the person using the tool has not received specific training for understanding and interpreting results [12]. The Questionnaire on Pain caused by Spasticity (QPS) turned out to be the only mixed-pain assessment tool. Its peculiarity is to make three different evaluations (self-report, health care operator and parents/caregivers) in two different moments and after a 1-week interval. Although fragility is a very complex situation to evaluate, the research in this field is still very limited and underrated, probably because of the many facets that should be considered when evaluating a patient with severe cognitive and physical impairments, which may lead the operator to underestimate the true intensity of the pain [38]. Our review paper has also highlighted that pain assessment tools which are now applied to adolescent patients had originally been made to assess the intensity of pain in the adult population suffering from chronic or degenerative pathologies. It is true that chronic pain negatively affects the adolescent population and impacts on daily life activities of the youth [36]. Social relations and absence from school are undoubtedly the most affected areas in an adolescent’s life [28]. Also, when assessing the intensity of pain in this young population set, the relationship with the parents and the child’s degree of involvement have to be taken into account [36]. In particular, the Pain Experience Questionnaire—parent version (PEQ-P) analyzes the parents’ stressful thinking about their child’s pain, which inevitably impacts the child life and compromises family dynamics and social behaviors, thus emphasizing once again the concept of pain being a complex biological, psychological and social experience [55].

As for the psychometric characteristics reported in Table 1, 3, and 4, it is important to underline that the use of the model suggested by Law [53] (Table 5) for assessing the available instruments may not be completely applicable in a given clinical setting. Several are the variables which establish both the validity and reliability of a tool, which should therefore be evaluated according to the psychometric characteristics of the tool as well as to the setting in which it is used [7].

Limitations

This review presents some limitations. In the search process, papers written in languages other than English or Italian were excluded, so it is possible that relevant findings were missed. In addition, we could not retrieve the full texts of potentially pertinent papers, so these studies were not included.

Conclusion

This review indicates the following key points:

-

1.

The cognitive and psychological development of adolescents requires multidimensional and specific pain assessment scales.

-

2.

The six pain assessment tools applicable to the adolescent population are multidimensional and self-reporting; five of them have good psychometric characteristics.

-

3.

No tool for the evaluation of adolescent pain is translated into Italian.

-

4.

The lack of tools specific for the adolescent population validated in Italian poses serious limitations on the way we approach this problem because it’s of utmost importance to use the right pain assessment tools to avoid the underestimation of this condition.

-

5.

The use of validated scales in Italian but not specific to adolescents could be in many cases limited and inadequate.

-

6.

It is very important to implement the validation of adolescent’s pain tools also in the Italian language.

References

Word Health Organization. Health for the world’s adolescents: a second chance in the second decade. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

Craig K, Korol C. Developmental issues in understanding assessing and managing pediatric pain. In: Walco G, Goldshnieder K, editors. Pediatric Pain Management in Primary Care A Pratical Guide. New York: Humana Press; 2008.

Friedrichsdorf SJ, Giordano J, Desai Dakoji K, Warmuth A, Daughtry C, Schulz CA. Chronic pain in children and adolescents: diagnosis and treatment of primary pain disorders in head, abdomen, muscles and joints. Children. 2016;3(42):1–26.

Schappert SM, Bhuiya F. Availability of pediatric services and equipment in emergency departments: United States, 2006. National Health Statistics Report. 2012, p. 1–21

Gilbert-MacLeod CA, Craig KD, Rocha EM, Mathias MD. Everyday pain responses in children with and without developmental delays. J Pediatr Psycol. 2000;25(5):301–8.

Perquin CW, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Hunfeld JA, Bohnen AM, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, Passchier J. Pain in children and adolescents: a common experience. Pain. 2000;87(1):51–8.

Bai J, Jiang N. Were are we: a systematic evaluation of the psychometric properties of pain assessment scales for use in Chinese children. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(4):617–31.

Amit J, Ramakrishna Y, Munshi AK. Measurement and assessment of pain in children—a review. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2012;37(2):125–36.

Ameringer S. Measuring pain in adolescents. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23(3):201–4.

Ecclestone C, Clinch J. Adolescent chronic pain and disability: a review of the current evidence in assessment and treatment. Paediatr Child Health. 2007;12(2):117–20.

Van Hulle VC. Nurses perceptions of children’s pain: a pilot study of cognitive representations. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33(3):290–301.

Stevens BJ, Harrison D, Rashotte J, Yamada J, Abbott LK, Coburn G, et al. Pain assessment and intensity in hospitalized children in Canada. J Pain. 2012;13(9):857–65.

Latina R, Mauro L, Mitello L, D’Angelo D, Caputo L, De Marinis MG, et al. Attitude and knowledge of pain management among Italian Nurses in Hospital settings. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(6):959–67.

Jacob E, Mack AK, Savedra M, Van Cleve L, Wilkie DJ. Adolescent pediatric pain tool for multidimensional measurement of pain in children and adolescents. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15(3):694–706.

Sturla Frank L, Smith Greenberg C, Stevens B. Pain assessment in infant and children. Pediatr Clin. 2000;47(3):417–512.

Rolin-Gilman C, Fournier B, Cleverley K. Implementing best practice guidelines in pain assessment and management on a women's psychiatric inpatient unit: exploring patients' perceptions. Pain Manag Nurs. 2017;18(3):170–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2017.03.002

Goodman JE, McGrath PJ. The epidemiology of pain in children and adolescents: a review. Pain. 1991;46(3):247–64.

McGrath PA, Gillespine J. Pain assessment in children and adolescents. In: Turk D, Melzac R, editors. Handbook of Pain Assessment. 2nd ed. New York: Guilfored Press; 2001. p. 97–118.

Hadjistravopoulos T, von Baeyer C, Craig K. Pain assessment in people with limited communication. In: Turk D, Melzack R, editors. Handbook of Pain Assessment. New York: Guilord Press; 2001. p. 134–49.

Breau LM, Burkitt C. Assessing pain in children with intellectual disabilities. Pain Res Manage. 2009;14(2):116–20.

Stevens B. Composite measures of pain. In: Finley GA, McGrath PJ, editors. Measurement of pain in infants and children. Seattle: IASP Press; 1998. p. 161–78.

Eccleston C, Jordan A, McCracken LM, Sleed M, Connel H, Clinch J. The Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ): development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess the impact of chronic pain on adolescents. Pain. 2005;118(1–2):263–70.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Essentials of nursing research. Appraising evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2014.

Law M, King G, MacKinnon E, Murphy C, Russel D. All about outcomes Thorofare. NJ: Slack Inc; 2000.

Savedra MC, Holzemer WL, Tesler MD, Wilkie DJ. Assessment of post operation pain in children and adolescents using the adolescent pediatric pain tool. Nurs Res. 1993;42(1):5–9.

Well S, Merlijn V, Passchier J, Koes B, van der Wouden J, van Suijlekom-Smit L, et al. Development and psychometric properties of a pain-related problem list for adolescents (PPL). Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58(2):209–15.

Varni JW, Thompson KL, Hanson V. The Varni/Thompson Pediatric Pain Questionnaire. I. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 1987;28(1):27–38.

Guite JW, Logan DE, Simons LE, Blood EA, Kerns RD. Readiness to change in pediatric chronic pain: initial validation of adolescent and parent versions of the Pain Stages of Change Questionnaire. Pain. 2011;152(10):2301–11.

McGrath PA, Seifert CE, Speechley KN, Booth JC, Stitt L, Gibson MC. A new analogue scale for assessing children’s pain: an initial validation study. Pain. 1996;64(3):435–43.

Hester NO, Foster R, Kristensen K. Measurement of pain in children: generalizability and validity of the pain ladder and the poker chip tool. In: Tyler Krane, editor. Advances in pain research and therapy, vol. 15. New York: Raven Press; 1990. p. 179–98.

Nelli JM, Nicholson K, Lakha FS, Louffat AF. Use of a modified Comprehensive Pain Evaluation Questionnaire: characteristics and functional status of patients on entry to a tertiary care pain clinic. Qual Life Res. 2012;17(2):75–82.

Merkel SI, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz JR, Malviya S. The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children. Pediatr Nurs. 1997;23(3):293–7.

Jay SM, Ozolins M, Elliott CH, Caldwell S. Assessment of children’s distress during painful medical procedures. Health Psychol. 1983;2:133–47.

Bursch B, Tsao JCI, Meldrum M, Zeltzer LK. Preliminary validation of a self-efficacy scale for child functioning despite chronic pain (child and parent versions). Pain. 2006;125(1–2):35–42.

Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:227–9.

Hermann C, Hohmeister J, Zohsel K, Tuttas ML, Flor H. The impact of chronic pain in children and adolescents: development and initial validation of a child and parent version of the Pain Experience Questionnaire. Pain. 2008;135(3):251–61.

Abu-Saad HH, Kroonen E, Halfens R. On the development of a multidimensional Dutch pain assessment tool for children. Pain. 1990;43:249–56.

Geister TL, Quintanar-Solares M, Mona M, Aufhammer S, Asmus F. Qualitative development of the Questionnaire on Pain caused by Spasticity (QPS), a pediatric patient-reported outcome for spasticity-related pain in cerebral palsy. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(3):887–96.

Zernikow B, Mayerhoff U, Michel E, Wiesel T. Pain in pediatric oncology -children’s and parents’ perspectives. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(4):395–406.

Joint Commission International. Pain assessment and management: an organizational approach. Oakbrook Terrace: Joint Commission International; 2000.

McAuliffe L, Nay R, O’Donnell M, Fetherstonhaugh D. Pain assessment in older people with dementia: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(1):2–10.

de Knegt NC, Lobbezoo F, Schuengel C. Evenh. Self-reporting tool on pain in people with intellectual disabilities (STOP-ID!): a usability study. Augment Altern Commun. 2016;32(1):1–11.

Benini F, Barbi E, Gangemi M, Manfredini L, Messeri A, Papacci P. Il Dolore nel Bambino: Strumenti pratici di valutazione e terapia. Roma; 2010

Brouwers M, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182(18):839–42.

King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain. 2011;152(12):2729–38.

Italian Republic. Law 15 marzo 2010 no. 38. 2010

Herr K, Coyne PG, McCaffery M, Manworren R, Merkel S. Pain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Manag Nurs. 2011;12(4):230–50.

Italian Ministry of Heath. Quaderni del Ministero della Salute no. 6. Roma; 2012

Wager J, Hechler T, Darlington AS, Hirschfeld G, Vocks S, Zernikow B. Classifying the severity of paediatric chronic pain—an application of the chronic pain grading. Eur J Pain. 2013;17(9):1393–402.

Italian National Institute of Statistic—ISTAT. Popolazione e famiglie/Stranieri e immigrati; 2015

Bates MS, Edwards WT. Ethnic variations in the chronic pain experience. Ethnic Disease. 1993;2(1):63–83.

Pain Associates in Nursing. Oucher! [Online].; 2009 [cited 2017 03 01. Available from: http://www.oucher.org/downloads/2009_Users_Manual.pdf.

Law M. Selecting outcomes measures in children’s rehabilitation: a comparison of methods. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:496–9.

Hunt A, Goldman A, Seers K, Crichton N, Mastroyannopoulou K, Moffat V, et al. Clinical validation of the paediatric pain profile. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46(1):9–18.

Turk DC, Monarch ES (2002) Biopsychosocial perspective on chronic pain. In: Turk DC, Gatchel RJ (eds) Psychological approaches to pain management: a practitioner’s handbook. New York

Weel S, Merlijn V, Passchier J, Koes B, van der Wouden J, van Suijlekom-Smit L, Hunfeld J. Development and psychometric properties of a pain-related problem list for adolescents (PPL). Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58(2):209–15.

Beyer JE, Denyes MJ, Villarruel AM. The creation, validation, and continuing development of the Oucher: a measure of pain intensity in children. J Pediatr Nurs. 1992;7(5):335–46.

Ambuel B, Hamlett KW, Marx CM, Blumer JL. Assessing distress in pediatric intensive care environments: the COMFORT scale. J Pediatr Psychol. 1992;17(1):95–109.

Pagé MG, Fuss S, Martin AL, Escobar EM, Katz J. Development and preliminary validation of the child pain anxiety symptoms scale in a community sample. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(10):1071–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsq034.

Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50(2):133–49.

Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales. Okla Nurse. 1988;33(1):8.

Ergün U, Say B, Ozer G, Yildirim O, Kocatürk O, Konar D, Kudiaki C, Inan L. Trial of a new pain assessment tool in patients with low education: the full cup test. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(10):1692–6.

Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The faces pain scale-revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93(2):173–83.

Solodiuk J, Curley MA. Pain assessment in nonverbal children with severe cognitive impairments: the individualized numeric rating scale (INRS). J Pediatr Nurs. 2003;18(4):295–9.

Lyon F, Boyd R, Mackway-Jones K. The convergent validity of the Manchester pain scale. Emerg Nurse. 2005;13(1):34–8.

Breau LM, McGrath PJ, Camfield CS, Finley GA. Psychometric properties of the non-communicating children's pain checklist-revised. Pain. 2002;99(1–2):349–57.

McCaffery M, Beebe A. Myths & facts about pain in children. Nursing. 1990;20(7):81.

Beyer JE, Ashley LC, Russell GA, DeGood DE. Pediatric pain after cardiac surgery: pharmacologic management. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1984;3(6):326–34.

Kerns RD, Haythornthwaite J, Rosenberg R, Southwick S, Giller EL, Jacob MC. The pain behavior check list (PBCL): factor structure and psychometric properties. J Behav Med. 1991;14(2):155–67.

Crombez G, Bijttebier P, Eccleston C, Mascagni T, Mertens G, Goubert L, Verstraeten K. The child version of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS-C): a preliminary validation. Pain. 2003;104(3):639–46.

Hermann C, Hohmeister J, Zohsel K, Tuttas ML, Flor H. The impact of chronic pain in children and adolescents: development and initial validation of a child and parent version of the pain experience questionnaire. Pain. 2008;135(3):251–61.

Stallard P, Williams L, Velleman R, Lenton S, McGrath PJ, Taylor G. The development and evaluation of the pain indicator for communicatively impaired children (PICIC). Pain. 2002;98(1–2):145–9.

Rossato LM, Magaldi FM. Multidimensional tools: application of pain quality cards in children. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2006;14(5):702–7.

Scott J, Huskisson EC. Graphic representation of pain. Pain. 1976;2(2):175–84.

Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. What is the maximum number of levels needed in pain intensity measurement? Pain. 1994;58(3):387–92.

Tesler MD, Savedra MC, Holzemer WL, Wilkie DJ, Ward JA, Paul SM. The word-graphic rating scale as a measure of children's and adolescents' pain intensity. Res Nurs Health. 1991;14(5):361–71.

McGrath PJ. Paediatric pain: a good start. Pain. 1990;41(3):253–4.

Hester NK. The preoperational child's reaction to immunization. Nurs Res. 1979;28(4):250–5.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Flavio Marti, Antonella Paladini, Giustino Varrassi and Roberto Latina have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article, go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5817594.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marti, F., Paladini, A., Varrassi, G. et al. Evaluation of Psychometric and Linguistic Properties of the Italian Adolescent Pain Assessment Scales: A Systematic Review. Pain Ther 7, 77–104 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-018-0093-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-018-0093-x