Abstract

Introduction

There is an on-going debate about what qualifies one to be called a “pain physician” and who can run the “pain clinic”. Currently, the discipline of anesthesiology is producing the majority of pain physicians. A literature search was unable to find data for any Pakistani or other South Asian countries with regards to general practitioner (GP) knowledge about pain clinics and pain physicians. The main objective of this study was to assess the awareness of GPs regarding the existence of the pain clinic and pain physician.

Methods

A total of 411 GPs were included in this cross-sectional survey. A questionnaire consisting of ten questions was designed to identify their knowledge about the existence of pain clinics and pain physicians. Questionnaires were completed in the field and edited for the inconsistencies and in-completeness.

Results

The results showed that only 52.6% of GPs were aware of the existence of pain clinics. The survey showed that 37.5% believe neurologists are the pain physicians and only 10.9% know that pain clinics are run by anesthesiologist. The vast majority (85.0%) are unaware of the modern pain relieving methods used in pain clinics.

Conclusion

The survey indicates that nearly half of the GPs are unaware of the existence of pain clinics and pain physicians, and the majority of GPs are unaware of new pain relieving methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The area of pain medicine is considered a new discipline and has evolved significantly over the last 2–3 decades. The history of this discipline began when Dr. Rovenstine, an anesthesiologist, set up the first pain clinic in 1936 in New York to treat patients suffering from pain that was not relieved by conventional methods [1]. Later, during World War II, Dr. John Bonica recognized the under treatment of pain in war victims. He introduced the multidisciplinary approach to treat such patients and subsequently the first multidisciplinary pain clinic was established in 1940 in Seattle [2]. Since then thousands of pain clinics have evolved across the world.

In Pakistan, the pain medicine specialty was introduced in the mid-80s, but to date very few established pain clinics exist. Aga Khan University is the first private medical international university of Pakistan that has taken the initiative to bridge the widening gaps in the health care and education setup in Pakistan. The Department of Anesthesiology in the university is the pioneer in setting up the first formal pain clinic in Pakistan. This is an anesthesiologist led pain clinic, which treats a variety of cases such as low back pain, cancer pain, complex regional pain syndrome, neuropathic pain, and myofacial pain, etc. The clinic offers a complete evaluation and treatment, including different kinds of interventional pain procedures. In this tertiary care center, all appropriate consultative and therapeutic services are available, e.g., neurosurgery, neurology, oncology, orthopedic surgery, psychology and physical therapist. In the last decade, several teaching institutions have also started pain clinics with basic facilities to cater the huge 20 million populations of Karachi.

There is an on-going debate about who qualifies as a pain physician. Anesthesiologists, considering their skills in pain management using regional techniques and their pharmacological knowledge about pain medicines, are playing an important role in these multidisciplinary teams [3]. The discipline of anesthesiology currently makes up the majority of pain physicians in the USA and anesthesiologists hold the majority of all available pain boards. However, a significant minority of self-declared pain physicians hold no pain-related board certification [4].

During a literature search, we were unable to find any data from Pakistani or other South Asian neighboring countries to see whether general practitioners are aware of the existence of pain clinics and pain physicians. Moreover, an earlier survey at our hospital showed poor and unsatisfactory knowledge of chronic pain patients regarding pain clinics and the role of anesthesiologist as a pain physician. In that survey, only 47% of patients knew about the existence of the pain clinic and very few knew the role of the anesthesiologist as a pain physician [5]. There is also literature evidence that most patients even in the developed country are not aware of the role of anesthesiologists in pain clinics [6]. We made a very strong observation that general practitioners (GPs) in Karachi are unaware of the existence of pain clinics, and the role of the anesthesiologist in running such pain setups, and also observed that chronic pain patients have usually had several opinions from different disciplines prior to visiting our pain clinic. Also, GPs in the city did not appear to be very aware of the other pain modalities available if conventional pharmacological treatment fails. Therefore, the main objective of the study was to assess the awareness of GPs regarding the existence of pain clinic and availability of other pain modalities if conventional methods fail. Their knowledge about the pain physician running the pain clinic was examined.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional survey was conducted for a period of 1 year after the approval from the Hospital Ethics Committee at Aga Khan University. The survey was financially supported by the Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan. This article does not contain findings from either interventional studies in humans or animal studies that have been performed by any of the authors. All participants gave informed consent for their participation in the survey.

Participant Selection

An up-to-date list of all GPs in Karachi was obtained from Pakistan Medical Association (PMA) office, Karachi. This list of 6,489 GPs was further verified by a list prepared by a multinational pharmaceutical company, and the final list was then verified by the investigators in randomly selected areas of Karachi. From the last updated list, a random sample of GPs, proportionate to the numbers in each of the 15 towns in Karachi, was generated. Overall 448 GPs were approached to obtain consent from 411 GPs (the required sample size) for their participation in the survey.

Questionnaire Design and Implementation

A questionnaire was designed and pre-tested with five GPs. The survey consisted of ten questions to identify the knowledge of GPs about the existence of pain clinics, pain physicians, modern methods of pain control, and strategies to refer the case when conventional treatment fails. The questionnaire contained one item per question and participants were also requested to provide basic demographic information (age, sex, years of practice, basic qualification) and their usual practice trends. A trained personnel conducted interviews in person from Monday to Friday from 9.00 a.m. to 5.00 p.m. These were based on a pre-coded questionnaire and conducted in both English and the national language of Urdu. Questionnaires completed in the field were edited for the inconsistencies and in-completeness. In case of any missing entry, the questionnaire was re-sent to interviewers in the field for completion.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size for this survey was calculated with an anticipated prevalence of knowledge about pain clinics and pain physician among GPs (as unknown). It was expected that 50% of participants had knowledge about pain clinics and pain physician, so the prevalence of knowledge was estimated within 5% level of precision with 95% confidence interval. The complete survey forms were double entered by two data entry operators. All statistical analyses were performed using statistical packages for social science version 19 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL). Frequency and percentage were computed for all questions. Mean and standard deviation were estimated for age.

Results

Survey was conducted in 15 locations according to the distribution of the participant as mentioned in Table 1. The demographic characteristics of all participants enrolled in this survey are shown in Table 2. The vast majority of GPs (64.3%) had less than 10 years of experience and the minority (28.2%) had postgraduate diploma. Of the GPs included in the survey, 34.5% attended 1–2 continued medical education (CME) programs per year, while 65.5% had never attended such activities.

Of the total study population, 52.6% GPs were aware of the existence of a pain clinic in the city and their major source of information was the Internet and scientific literature (Table 3). The remaining 47.4% were not aware of the existence of the pain clinic, and within this group 11.8% had never heard of such facility as a pain clinic, all of whom were experienced GPs (more than 25 years). The majority of GPs (37.5%) in the city believed that neurologists are the pain physicians and only 10.9% knew that the pain clinic is mainly run by anesthesiologists in Pakistan (Table 4).

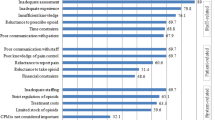

Around 92.7% of GPs had seen patients with a history of pain for more than 3 months (classified as chronic pain). Backache was the most commonly reported pain at GP’s clinics across the city, followed by knee joint pain and headache. The majority of GPs (93.9%) use simple analgesics in combination (consisting of more than one analgesic group) for chronic pain by oral, intravenous, or intramuscular route. The survey showed that 32.0% of GPs refer their patients to a tertiary care hospital, mainly to the orthopedic and neurology discipline, if pain does not get relieved, whereas 42.1% start investigating (by blood and radiology) to find the cause of unrelieved pain. The vast majority of GPs (85.0%) were unaware of the modern pain relieving methods (epidural and facets blocks, and radiofrequency treatment) used for the treatment of chronic pain. It was also found that GPs who were attending regular educational programs or CME were well aware of the new discipline of pain medicine and modern way of treatment.

Discussion

The important finding of this survey is that nearly half of GPs do not know about the existence of pain clinics in Karachi. In this group, a predominant feature was the representation of experienced GPs who did not have any evidence of attending CME programs in the last 2–3 years. However, most of these GPs were minor postgraduate diploma holders early in their careers. This shows the importance of continued professional development for all GPs even if they are qualified.

In Pakistan, the graduates of Pakistan Medical & Dental Council (PMDC) registered medical colleges require 1 year house job training to get license for practicing. In this regard, the consideration of CME credit hours at the time of renewal of licensing certificate is of utmost important. This is usual practiced in many developed countries but unfortunately this does not happen in Pakistan and many other developing countries. However, some of the universities in Pakistan have introduced CME credit hours to be considered at the time of credentialing and re-credentialing of any physician. We strongly feel that the dissemination of findings from the survey to the PMDC (licensure body) through the HEC should be the first step to sensitize this issue on a larger scale.

A past survey showed that only 47% of patients knew about the existence of pain clinics and very few knew the role of anesthesiologist as a pain physician [5], and in the literature, there is evidence that most patients even in the developed country are not aware of the role of anesthesiologists in pain clinics [6]. Across the world, there is much confusion about who qualifies as a pain physician. We know there is no primary residency in pain medicine, although informal pain fellowships have existed for several years in many countries. In 1993, the American Board of Anesthesiology (ABA) began offering the examination for the certificate of added qualification in pain management [7]. In 1998, the ABA, the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (ABPMR), and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) pooled resources to create a multidisciplinary pain medicine examination with questions submitted from members of the three organizations.

According to data listed in Journal of the American Medical Association’s 2003 graduate medical education issue, 181 pain fellows were enrolled in the 264 slots available within anesthesiology pain fellowship programs [8]. In Pakistan, currently all pain setups are being run by anesthesiologists and there is only one fellowship program exists, which is offered to the anesthesiologist only after the successful completion of anesthesia residency program. Considering the findings of our survey, we suggest the need to educate GPs in Pakistan about the role of the anesthesiologist and the qualifications/training required to be a pain physician.

In this survey, we found that more than 60% of our GPs thought that pain clinics are run mainly by neurologists and general physicians. Prior to this survey, we were not aware that the majority of GPs lack the knowledge about pain clinic and the role of anesthesiologist. Our finding that 85% of our GPs are severely deficient in basic knowledge of pain relieving methods and not aware about the availability of various interventional techniques in pain clinics is alarming. Considering their practice trends, more than 90% of GPs regularly see chronic pain patients with deficient basic knowledge of pain medicines. Only the minority refer patients to a tertiary care center if conventional treatment fails, while the remaining majority do not refer their patients. These findings have recently been shared with the Pakistan Society for Treatment and Study of Pain and the executive committee has decided to conduct awareness session in five big cities of Pakistan in 2013. Simultaneously, we are also planning to approach an international funding agency for organizing basic pain education courses for general practitioners on a regular basis.

The limitations of the study include that it was carried out at only one city and therefore might not represent the Pakistani population, as both education and clinical practices differ from city to city. In addition, we did not aim to find the patient volume of individual GPs, which is an important variable in overall practice trends.

In summary, our survey indicates that nearly half of GPs in Karachi are not aware about the existence of pain clinics. They are also not aware about the role of the anesthesiologist in pain management and lack knowledge regarding pain relieving methods. The Internet and/scientific literature are the major sources of information; however, the majority of GPs in this population are not attending regular CME activities of any kind and do not feel the need to do so. Further work needs the requirement of education/awareness sessions and establishment of pain service in developing countries like Pakistan.

References

Swerdlow M. A history of the early years of pain relief clinics in the UK and Ireland. Painwise: Irish J Pain Med. 2002;1:19–20.

Loeser JD. Multidisciplinary pain programs. In: Loeser JD (ed.) Bonica’s management of pain. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001, p. 255–264.

Poppe C, Devulder J, Mariman A, Mortier E. Chronic pain therapy: an evolution from solo-interventions to a holistic interdisciplinary patient approach. Acta Clin Belg. 2003;58:92–7.

Ricardo M. Buenaventura, MD, Thomas D. Mc Sweeney, et al. The qualifications of pain physicians in Ohio. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:1746–52.

Hussain AM, Afshan G. Knowledge of patients about pain clinic and pain physicians: a cross sectional survey at a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Pain. 2008;22:132–6.

Tohmo H, Palve H, Illman H. The work, duties and prestige of Finnish anesthesiologists: patients’ view. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:664–66.

American Board of Medical Specialties. 2003 American Board of Medical Specialties annual report and reference handbook. American Board of Medical Specialties Web site. Available at: http://www.abms.org/statistics.asp. Accessed October 12, 2003.

American Medical Association. Appendix II: graduate medical education. JAMA. 2003;290:1234–48.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Mansoor Khan, Ms. Zohra Ismail and Ms. Shumaila Minhaz for their excellent technical assistance toward this manuscript. The survey was financially supported by Higher Education Commission (HEC), Pakistan. Dr. Gauhar Afshan is the guarantor for this article and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole. This work was presented at 14th World Congress, organized by IASP (International association for study of pain) August 27–30, 2012, Milan, Italy, and 6th South Asian Regional Pain Society (SARPS) congress January 13–15, 2012, Karachi, Pakistan.

Conflict of interest

Drs. Gauhar Afshan, Aziza M. Hussain, and Syed I. Azam declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The survey received approval from the Hospital Ethics Committee, Aga Khan University. This article does not contain findings from either interventional studies in humans or animal studies that have been performed by any of the authors. All participants gave informed consent for their participation in the survey.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Afshan, G., Hussain, A.M. & Azam, S.I. Knowledge about Pain Clinics and Pain Physician among General Practitioners: A Cross-sectional Survey. Pain Ther 2, 105–111 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-013-0014-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-013-0014-y