Abstract

Introduction

Oral antiviral medications are important tools for preventing severe COVID-19 outcomes. However, their uptake remains low for reasons that are not entirely understood. Our study aimed to assess the association between perceived risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes and oral antiviral use among those who were eligible for treatment based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines.

Methods

We surveyed 4034 non-institutionalized US adults in April 2023, and report findings from 934 antiviral-eligible participants with at least one confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection since December 1, 2021 and no current long COVID symptoms. Survey weights were used to yield nationally representative estimates. The primary exposure of interest was whether participants perceived themselves to be “at high risk for severe COVID-19.” The primary outcome was use of a COVID-19 oral antiviral within 5 days of suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Results

Only 18.5% of antiviral-eligible adults considered themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 and 16.8% and 15.9% took oral antivirals at any time or within 5 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection, respectively. In contrast, 79.8% were aware of antiviral treatments for COVID-19. Perceived high-risk status was associated with being more likely to be aware (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR]: 1.11 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.03–1.20]), to be prescribed (aPR 1.47 [95% CI 1.08–2.01]), and to take oral antivirals at any time (aPR 1.61 [95% CI 1.16–2.24]) or within 5 days of infection (aPR 1.72 [95% CI 1.23–2.40]).

Conclusions

Despite widespread awareness of the availability of COVID-19 oral antivirals, more than 80% of eligible US adults did not receive them. Our findings suggest that differences between perceived and actual risk for severe COVID-19 (based on current CDC guidelines) may partially explain this low uptake.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Though oral antiviral medications are important tools to prevent severe COVID-19 outcomes, uptake remains low for reasons that are not entirely understood. |

We investigated the relationship between perceived risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes and use of oral antiviral treatment for COVID-19 among those who were eligible for treatment. |

What was learned from the study? |

Out of 934 non-institutionalized US adults surveyed in April 2023 who were antiviral-eligible with at least one confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection since December 1, 2021, only 18.5% considered themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 and 15.9% took oral antivirals within 5 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection. |

Perceived high-risk status was associated with being more likely to be aware, to be prescribed, and to take oral antivirals at any time or within 5 days of infection. |

Differences between perceived and actual risk for severe COVID-19 may partially explain low oral antiviral uptake. |

Introduction

In addition to COVID-19 vaccination [1], oral antiviral medications such as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and molnupiravir are important tools for preventing severe COVID-19 outcomes. These drugs were first approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) in December 2021 for individuals at high risk for severe COVID-19 disease [2, 3], based on clinical trials in the summer and fall of 2021 showing substantial reductions in hospitalizations and deaths among high-risk, non-hospitalized and unvaccinated adults with SARS-CoV-2 infection [4, 5]. In the Omicron era, real-world effectiveness of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir against COVID-19-related hospitalizations, disease progression, and death has been demonstrated in a number of different outpatient settings, including among individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 immunity through infection or vaccination, with a high level of protection for those older than 65 or with comorbidities [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Evidence of molnupiravir effectiveness among high-risk vaccinated adults, however, is mixed [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The benefits of oral antiviral therapy may also extend beyond the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection [22, 23].

In March 2022, the federal government launched the nationwide Test-to-Treat Initiative, which sought to provide testing, assessment by a health care provider, and COVID-19 oral antiviral prescription for eligible individuals in one visit at low or no cost [24]. The program was expanded to additional locations in May 2022, with telehealth options available. An analysis of Test-to-Treat program locations in July 2022 found barriers, such that high-poverty ZIP codes and small towns and rural areas still had less access to program locations than those in metropolitan areas [25]. To further reduce barriers and increase access, the FDA revised the EUA in July 2022 to authorize state-licensed pharmacists to prescribe COVID-19 oral antiviral medications to eligible patients [26], and, in February 2023, the FDA again revised the EUA to permit oral antiviral prescription without documentation of a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 infection [27]. Despite the efforts to increase awareness and reduce barriers, uptake of COVID-19 antivirals has been low, with only 32% of nonhospitalized high-risk patients with SARS-CoV-2 evaluated between April 2022 and June 2023 as part of a multistate clinical cohort prescribed antiviral treatment [28].

To help identify potential reasons for low utilization of COVID-19 oral antivirals during a period of Omicron variant dominance [29], we characterized participants’ perceived risk for severe COVID-19 and determined whether perceived risk was associated with the use of COVID-19 oral antiviral treatment among those who were eligible for treatment based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines.

Methods

Design, Setting and Participants

Between April 17 and April 26 of 2023, Ipsos conducted an online cross-sectional survey (in English and Spanish) among individuals 18 years of age and older randomly sampled using an equal probability selection method from the national opt-in Ipsos KnowledgePanel of 55,000 non-institutionalized US adults [30]. Adults were recruited to the KnowledgePanel using address-based sampling to improve population coverage and provide a more effective means of recruiting hard-to-reach individuals, including mobile phone-only and non-Internet households. Households without an Internet connection were provided with free Internet-connected tablet computers. After agreeing to join the KnowledgePanel, members completed a short demographic survey, including questions on self-reported gender, age, race/ethnicity, education, census region and metropolitan area, household income, home ownership status, household size, and language dominance for English and Spanish speakers. Ipsos uses this information for panel sampling to invite a random sample that closely mirrors the US adult population. Individuals were invited by e-mail to participate in the current survey. After data collection, raking was used to create weights to account for any differential nonresponse and to ensure that survey estimates were representative of the non-institutionalized US adult population, using gender by age, race/ethnicity, census region by metropolitan status, education, household income, and language dominance distributions from the March 2022 Supplement of the Current Population Survey [31] and the 2021 American Community Survey [32]. This approach has been shown to provide reliable and nationally representative estimates that accurately quantify error when using smaller samples [33]. The full questionnaire used is included in the Supplementary Material.

To be included in the current analysis, participants had to have (1) at least one confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection since December 1, 2021 (when COVID-19 oral antivirals first became available in the United States); (2) not currently be experiencing long COVID symptoms; and (3) be eligible for COVID-19 antiviral treatment and thus at high risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes based on Centers for Disease Control (CDC) criteria for use [34]. These criteria included all individuals 50 years of age or older, and adults (of any age) who were: overweight or obese, pregnant or recently pregnant, a current smoker; or had diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or lung disease, cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis, asthma, liver disease, heart disease, high blood pressure, cerebrovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, depression, anxiety, another mental health condition, dementia, or an immunocompromising condition (i.e., a cancer, recent organ transplant, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], or taking immunosuppressive medications).

Aligned with previous work [35, 36], SARS-CoV-2 infection was defined based on self-report and included reporting having either a current infection (i.e., having a positive test in the past 2 weeks) or previously testing positive or being told by a healthcare provider that they had an infection. Possible but unconfirmed infections (i.e., “Not confirmed by a test or doctor, but I am pretty sure that I had COVID”) were excluded from analyses due to the uncertainty of COVID-19 status and a decreased likelihood of receiving antiviral treatment. Information on the timing of infection was used to limit the study sample to individuals with infections after COVID-19 oral antivirals were available. Individuals with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection were asked to indicate whether they were still experiencing symptoms more than 4 weeks after having COVID-19 that were not explained by something else [37]. These individuals were considered to have current long COVID and were excluded from analyses due to potential differences in risk assessment for severe COVID-19 and uncertainty about the timing of oral antiviral use in relation to the acute and post-acute phase of infection.

Exposures

The primary exposure of interest was whether an individual considered themselves to be “at high risk for severe COVID-19.”

Outcomes

The primary outcome was COVID-19 oral antiviral uptake within 5 days of suspected infection (vs. not), as recommended by the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel [38]. We also evaluated (i) oral antiviral uptake at any time after suspected infection (vs. not), (ii) whether individuals were prescribed an oral antiviral (vs. not), and (iii) whether participants were aware of COVID-19 antiviral treatments (vs. not). These outcomes were based on self-reported answers to questions about whether participants were aware of and prescribed COVID-19 oral antivirals at the time of their most recent infection, as well as questions about the timing of treatment initiation among those who used oral antiviral treatment (see Supplementary Material). Individuals who were eligible for but not prescribed oral antivirals were asked about reasons they were not prescribed treatment.

Statistical Analysis

We applied US population-representative survey weights to all prevalence estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used robust Poisson models to estimate prevalence ratios (PR) and corresponding 95% CIs for receiving a COVID-19 oral antiviral within 5 days of suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection (vs. not) by whether a participant perceived themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 (vs. not). Separate models were built for the other three secondary outcomes (awareness of COVID-19 antiviral treatments, prescription of an oral antiviral, and oral antiviral uptake at any time after a suspected infection) as well. Adjusted models included age group (18–34, 35–49, 50–64, and ≥ 65 years), self-reported gender (male or female), race/ethnicity (Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; White, non-Hispanic; and Other race or multiracial, non-Hispanic), education (high school graduate or less, some college, or Bachelor’s degree or above), household income (< $50,000, $50,000–$99,9999, ≥ $100,000), employment status (full-time, part-time, or not employed), geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), residence in a metropolitan statistical area (yes or no), any children under 18 in the household (yes or no), total doses of COVID-19 vaccine received (none, 1–2 doses, ≥ 3 doses), multiple SARS-CoV-2 infections (yes or no), timing of most recent SARS-CoV-2 infection (within the last month, 1–6 months ago, 6–12 months ago, > 12 months ago), and having at least one underlying condition (yes or no). All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the City University of New York (CUNY IRB 2022–0407). The Institutional Review Board determined that the study met the criteria for Human Subject Research Exemption based on collection of de-identified survey data only. Consent to receive survey invitations from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel is obtained during the recruitment process. Before responding to a survey, individuals must opt in and are reminded that their responses will be used for research purposes only and that they can choose not to answer any question.

Results

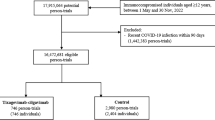

Out of 6663 invited panel participants, 4034 (60.5%) completed the survey. Of those who completed the survey, 1324 (32.7%) reported at least one confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection between December 2021 and April 2023 (Fig. 1). Of these, 934 (66.8%) were antiviral-eligible based on CDC criteria and did not report current long COVID symptoms. Median age was 53.9 years, 78.9% reported at least one underlying condition, and 63.4% had received three or more doses of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Only 18.5% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 15.9–21.2%) of antiviral-eligible adults without current post-acute symptoms considered themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19. Higher proportions of those who considered themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 (vs. not) had a household income of less than $100,000, were not currently employed full-time, had three or more doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, or reported at least one underlying condition (all p < 0.05; Table 1). Among specific conditions investigated, higher proportions of individuals with asthma, COPD/lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, liver disease, depression, or those who were overweight or obese or immunocompromised considered themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 (all p < 0.05).

Though 79.8% (95% CI 77.0–82.6%) of antiviral-eligible individuals reported being aware of COVID-19 antiviral treatment, only 18.6% (95% CI 16.1–21.2%) were prescribed oral antiviral treatments, 16.8% (95% CI 14.4–19.3%) took oral antivirals at all, and 15.9% (95% CI 13.5–18.3%) took oral antivirals within 5 days of suspected infection. Of those prescribed oral antiviral treatments, 89.6% (95% CI 84.9–94.3%) and 10.4% (95% CI 5.7–15.1%) reported being prescribed nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and molnupiravir, respectively. Among those who were prescribed oral antivirals but did not take them within 5 days of suspected infection, 66.3% (95% CI 46.3–86.3%) did not take the medications at all, while 11.9% (95% CI 0.0–26.8%) took them 6–10 days after suspected infection, and 21.8% (95% CI 4.9–38.7%) did not remember when they had taken them. Among those who were not prescribed oral antivirals, 56.0% (95% CI 52.2–59.7%) did not think they needed treatment, 24.8% (95% CI 21.5–28.1%) were unaware of antiviral treatments for COVID-19, 4.3% (95% CI 2.8–5.9%) asked for a prescription but their provider refused, and 14.9% (95% CI 12.1–17.6%) were not sure why they were not prescribed oral antivirals.

In crude analyses, higher proportions of individuals who considered themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 (vs. not) were aware of, prescribed, and took oral antivirals at all and within 5 days of suspected infection (Fig. 2). In multivariable analyses, use of oral antivirals within 5 days of a suspected infection was higher among those who considered themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR]: 1.72 [95% CI 1.23–2.40]; see Table 2). Awareness (aPR 1.11 [95% CI 1.03–1.20]), prescription (aPR 1.47 [95% CI 1.08–2.01]), and any use of oral antivirals (aPR 1.61 [95% CI 1.16–2.24]) were also higher among those who considered themselves to be at high risk (See Supplementary Table 1 in the Supplemental Material).

Discussion

Despite widespread awareness of COVID-19 antivirals in our population-based sample of US adults, more than 80% of eligible individuals did not receive them at the time of their last infection. Low uptake of COVID-19 oral antivirals has been noted in other studies, even among eligible individuals who sought care or were in priority settings like nursing homes [11, 39,40,41]. Other studies have also highlighted that lack of use does not appear to be mainly a factor of lack of awareness. For example, in a convenience sample of US adults 65 and older in 37 states with a positive SARS-CoV-2 result between March 2021 and August 2022, two-thirds were aware of oral antiviral treatments, but only about a third sought treatment, and less than 2% reported use [42].

Our findings suggest that differences between perceived risk and actual risk for severe COVID-19 (based on current CDC guidelines) may partially explain low uptake. We found that less than one in three individuals 50 or older and less than one in five individuals of any age at seemingly high risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes perceived themselves to be so, and risk perception was significantly associated with oral antiviral uptake. Specifically, individuals who perceived themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 were 1.72 times more likely to report taking oral antivirals within 5 days of suspected infection. Though previous studies have found an association between having a higher COVID-19 risk perception and acceptance of preventive behaviors, such as masking, social distancing, and vaccination [43, 44], to our knowledge, this is one of the only studies to have looked at perceived risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes and oral antiviral use. While assessing one’s own risk for severe COVID-19 based on underlying comorbidities may be more complicated and rely more heavily on discussions with a medical provider, age-based risk should be more straightforward to assess. Thus, we were surprised to find no significant difference in perceived risk by age. Our findings suggest the need for additional strategies to support individuals in better assessing their risk for severe COVID-19. Medical providers are likely key for helping to assess risk of severe illness. A recent survey of non-institutionalized US adults found that 64% of respondents 65 years and older indicated that they would take oral antivirals if they tested positive for a SARS-CoV-2 infection, and 93% indicated that they would take oral antiviral treatment if their doctor recommended it to them [45], underscoring the importance of physician recommendation for improving oral antiviral uptake.

Our findings also give some insight into other possible reasons for non-use; we found that among eligible individuals who were not prescribed oral antivirals for their last SARS-CoV-2 infection, more than half did not think they needed it, while a healthcare provider refused a prescription for less than 5% of individuals. Using data from three rounds of the US Census Household Pulse Survey collected between June and August 2022, an analysis of reasons for not receiving oral antiviral treatment among individuals 65 or older with at least mild symptoms cited not feeling very sick (20.6%) and not thinking they needed treatment (16.4%) as the most common reasons for not taking oral antivirals, followed by not having the treatment offered or recommended to them by a healthcare provider (14.5%) [46]. The same study also found that not seeing oneself as a member of a high-risk group was a fairly uncommon reason cited for not taking oral antivirals (4.9%). This is surprising, given our finding that the majority of antiviral-eligible individuals do not perceive themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes.

Though the survey design used in this study used sampling and weighting methods to reduce any bias resulting from sociodemographic differences in recruitment and response rates and has been shown to provide reliable and nationally representative estimates for other COVID indicators [33], we were unable to account for potential nonresponse bias related to SARS-CoV-2 infection history or oral antiviral use. For example, if people who used oral antivirals were more likely to complete the survey, estimates may be inflated. However, our approach benefits from the ability to reflect perceived risk, COVID-19 outcomes, antiviral eligibility, and oral antiviral use among those who may not have accessed the healthcare system when they last had COVID-19.

Our study has several other limitations worth noting. Data were self-reported, and there is the potential for misclassification and reporting bias. However, studies comparing self-reported COVID-19 vaccine status with electronic health records or vaccine registries have found more than 90% agreement between the two [47,48,49]. Further, self-reported health conditions [50] and use of medication [51] have been found to have high specificity and moderate sensitivity; thus, we may have underestimated the prevalence of health conditions or oral antiviral use. Relatedly, our estimates of SARS-CoV-2 infection timing and oral antiviral use were likely more accurate for more recent infections. In addition, because our definition of SARS-CoV-2 infection was based on self-reported diagnosis by a health care provider or testing, we would have missed asymptomatic infections and symptomatic infections among those who did not receive a COVID test or seek care (i.e., possible infections), leading to an underestimated prevalence of those with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In our sample, none of those with possible infections reported antiviral prescription. This group requires further investigation, however, because they may have barriers to knowledge, access to testing, and access to care that could get in the way of antiviral use.

The cross-sectional nature of this study made it impossible to determine the temporality of responses, since risk and outcomes were assessed at the same time. While one might predict an individual’s perceived risk to influence their decisions around treatment once sick, one might also predict that experience with an illness might influence that individual’s perception of their risk going forward (e.g., if their symptoms were very mild). We did not ask about the severity or nature of symptoms experienced by individuals at the time of their last SARS-CoV-2 infection, which might be important factors to investigate further to better understand what influences an individual to seek antiviral treatment. In addition, participants were given only two possible reasons for non-use of oral antivirals, which limited our ability to better understand non-use. We plan to conduct a more granular evaluation of barriers to oral antiviral use, including elements of both patient and provider decision-making following the transition of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir and molnupiravir to the commercial market in November 2023 in the United States [52].

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that less than 20% of antiviral-eligible adults (based on CDC criteria for high risk) perceived themselves to be at high risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes. This misperception of risk status, and thus antiviral eligibility, may be a contributor to suboptimal COVID-19 oral antiviral uptake to date, despite broad awareness of COVID-19 treatment options. Our findings suggest the need for additional strategies to ensure that individuals better under their COVID-19 risk, which may improve uptake of available treatment options.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Rahmani K, Shavaleh R, Forouhi M, Disfani HF, Kamandi M, Oskooi RK, et al. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in reducing the incidence, hospitalization, and mortality from COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;26(10): 873596.

Office of the Commissioner. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes First Oral Antiviral for Treatment of COVID-19. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-first-oral-antiviral-treatment-covid-19

Office of the Commissioner. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Additional Oral Antiviral for Treatment of COVID-19 in Certain Adults. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-additional-oral-antiviral-treatment-covid-19-certain

Jayk Bernal A, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, Kovalchuk E, Gonzalez A, Delos Reyes V, et al. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(6):509–20.

Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, Abreu P, Bao W, Wisemandle W, et al. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(15):1397–408.

Arbel R, Wolff Sagy Y, Hoshen M, Battat E, Lavie G, Sergienko R, et al. Nirmatrelvir use and severe Covid-19 outcomes during the omicron surge. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(9):790–8.

Dryden-Peterson S, Kim A, Kim AY, Caniglia EC, Lennes IT, Patel R, et al. Nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir for early COVID-19 in a large U.S. health system: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176(1):77–84.

Petrakis V, Rafailidis P, Trypsianis G, Papazoglou D, Panagopoulos P. The antiviral effect of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir during COVID-19 pandemic real-world data. Viruses. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15040976.

Najjar-Debbiny R, Gronich N, Weber G, Khoury J, Amar M, Stein N, et al. Effectiveness of Paxlovid in reducing severe coronavirus disease 2019 and mortality in high-risk patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(3):e342–9.

Ganatra S, Dani SS, Ahmad J, Kumar A, Shah J, Abraham GM, et al. Oral nirmatrelvir and ritonavir in nonhospitalized vaccinated patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(4):563–72.

Shah MM, Joyce B, Plumb ID, Sahakian S, Feldstein LR, Barkley E, et al. Paxlovid associated with decreased hospitalization rate among adults with COVID-19—United States, April–September 2022. Am J Transplant. 2023;23(1):150–5.

Aggarwal NR, Molina KC, Beaty LE, Bennett TD, Carlson NE, Mayer DA, et al. Real-world use of nirmatrelvir-ritonavir in outpatients with COVID-19 during the era of omicron variants including BA.4 and BA.5 in Colorado, USA: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00011-7.

Schwartz KL, Wang J, Tadrous M, Langford BJ, Daneman N, Leung V, et al. Population-based evaluation of the effectiveness of nirmatrelvir-ritonavir for reducing hospital admissions and mortality from COVID-19. CMAJ. 2023;195(6):E220–6.

Butler CC, Hobbs FDR, Gbinigie OA, Rahman NM, Hayward G, Richards DB, et al. Molnupiravir plus usual care versus usual care alone as early treatment for adults with COVID-19 at increased risk of adverse outcomes (PANORAMIC): an open-label, platform-adaptive randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10373):281–93.

Gbinigie O, Ogburn E, Allen J, Dorward J, Dobson M, Madden TA, et al. Platform adaptive trial of novel antivirals for early treatment of COVID-19 In the community (PANORAMIC): protocol for a randomised, controlled, open-label, adaptive platform trial of community novel antiviral treatment of COVID-19 in people at increased risk of more severe disease. BMJ Open. 2023;13(8): e069176.

Schilling WHK, Jittamala P, Watson JA, Boyd S, Luvira V, Siripoon T, et al. Antiviral efficacy of molnupiravir versus ritonavir-boosted nirmatrelvir in patients with early symptomatic COVID-19 (PLATCOV): an open-label, phase 2, randomised, controlled, adaptive trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00493-0.

Wong CKH, Au ICH, Lau KTK, Lau EHY, Cowling BJ, Leung GM. Real-world effectiveness of molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir against mortality, hospitalisation, and in-hospital outcomes among community-dwelling, ambulatory patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection during the omicron wave in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet. 2022;400(10359):1213–22.

Xie Y, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Molnupiravir and risk of hospital admission or death in adults with covid-19: emulation of a randomized target trial using electronic health records. BMJ. 2023;7(380): e072705.

Evans A, Qi C, Adebayo JO, Underwood J, Coulson J, Bailey R, et al. Real-world effectiveness of molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir-ritonavir, and sotrovimab on preventing hospital admission among higher-risk patients with COVID-19 in Wales: a retrospective cohort study. J Infect. 2023;86(4):352–60.

Lin DY, Abi Fadel F, Huang S, Milinovich AT, Sacha GL, Bartley P, et al. Nirmatrelvir or molnupiravir use and severe outcomes from omicron infections. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(9): e2335077.

Paraskevis D, Gkova M, Mellou K, Gerolymatos G, Psalida Ν, Gkolfinopoulou K, et al. Real-world effectiveness of molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir as treatments for COVID-19 in high-risk patients. J Infect Dis. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiad324.

Xie Y, Choi T, Al-Aly Z. Molnupiravir and risk of post-acute sequelae of covid-19: cohort study. BMJ. 2023;25(381): e074572.

Xie Y, Choi T, Al-Aly Z. Association of treatment with nirmatrelvir and the risk of post-COVID-19 condition. JAMA Intern Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.0743.

How Test to Treat Works for Individuals and Families. Available from: https://aspr.hhs.gov/TestToTreat/Pages/process.aspx

Smith ER, Oakley EM. Geospatial disparities in federal COVID-19 test-to-treat program. Am J Prev Med. 2023;64(5):761–4.

Office of the Commissioner. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Pharmacists to Prescribe Paxlovid with Certain Limitations. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-pharmacists-prescribe-paxlovid-certain-limitations

Parkinson J. ContagionLive. 2023. FDA No Longer Requires Positive COVID-19 Test to Use 2 Antivirals. Available from: https://www.contagionlive.com/view/fda-no-longer-requires-positive-covid-19-test-to-use-2-antivirals

Levy ME, Burrows E, Chilunda V, Pawloski PA, Heaton PR, Grzymski J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antiviral prescribing gaps among non-hospitalized high-risk adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad796.

Ma KC, Shirk P, Lambrou AS, Hassell N, Zheng XY, Payne AB, et al. Genomic surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 variants: circulation of omicron lineages—United States, January 2022–May 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(24):651–6.

Ipsos. Be Sure with KnowledgePanel®. 2018. Available from: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/18-11-53_Overview_v3.pdf

US Census Bureau. Current Population Survey Datasets [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/data/datasets.html

US Census Bureau. Data Releases. Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/news/data-releases.2021.html#list-tab-1133175109

Bradley VC, Kuriwaki S, Isakov M, Sejdinovic D, Meng XL, Flaxman S. Unrepresentative big surveys significantly overestimated US vaccine uptake. Nature. 2021;600(7890):695–700.

CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023 [cited 2023 Jun 1]. People with Certain Medical Conditions. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

Qasmieh SA, Robertson MM, Teasdale CA, Kulkarni SG, Jones HE, McNairy M, et al. The prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and long COVID in U.S. adults during the BA.4/BA.5 surge, June-July 2022. Prev Med. 2023;169: 107461.

Robertson MM, Qasmieh SA, Kulkarni SG, Teasdale CA, Jones H, McNairy M, et al. The epidemiology of long COVID in US adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac961.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey: methods and further information. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/methodologies/covid19infectionsurveypilotmethodsandfurtherinformation

COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. Ritonavir-Boosted Nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid). Available from: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/antivirals-including-antibody-products/ritonavir-boosted-nirmatrelvir--paxlovid-/

Yan L, Streja E, Li Y, Rajeevan N, Rowneki M, Berry K, et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 pharmacotherapies among nonhospitalized US veterans, January 2022 to January 2023. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(8): e2331249.

McGarry BE, Sommers BD, Wilcock AD, Grabowski DC, Barnett ML. Monoclonal antibody and oral antiviral treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection in US nursing homes. JAMA. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.12945.

Monach PA, Anand ST, Fillmore NR, La J, Branch-Elliman W. Underuse of antiviral drugs to prevent progression to severe COVID-19—Veterans Health Administration, March–September 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2024;73(3):57–61.

Kojima N, Klausner JD. Usage and awareness of antiviral medications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among individuals at risk for severe COVID-19, March 2021 to 1 August 2022. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(4):775–6.

Cipolletta S, Andreghetti GR, Mioni G. Risk perception towards COVID-19: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084649.

Cheng Y, Liu RW, Foerster TA. Predicting intentions to practice COVID-19 preventative behaviors in the United States: a test of the risk perception attitude framework and the theory of normative social behavior. J Health Psychol. 2022;27(12):2744–62.

Ivy Oyegun E, Ategbole M, Jorgensen C, Fisher A, Hagen MB, Gutekunst L, et al. Factors associated with knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors regarding antiviral medications for COVID-19 among US adults. medRxiv. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.11.23299148v2.abstract.

Benchimol-Elkaim B, Dryden-Peterson S, Miller DR, Koh HK, Geller AC. Oral antiviral therapy utilization among adults with recent COVID-19 in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(7):1717–21.

Stephenson M, Olson SM, Self WH, Ginde AA, Mohr NM, Gaglani M, et al. Ascertainment of vaccination status by self-report versus source documentation: impact on measuring COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2022;16(6):1101–11.

Tjaden AH, Fette LM, Edelstein SL, Gibbs M, Hinkelman AN, Runyon M, et al. Self-reported SARS-CoV-2 vaccination is consistent with electronic health record data among the COVID-19 community research partnership. Vaccines (Basel). 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10071016.

Archambault PM, Rosychuk RJ, Audet M, Bola R, Vatanpour S, Brooks SC, et al. Accuracy of self-reported COVID-19 vaccination status compared with a public health vaccination registry in Québec: observational diagnostic study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023;16(9): e44465.

Xie D, Wang J. Comparison of self-reports and biomedical measurements on hypertension and diabetes among older adults in China. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1664.

Grabowski MK, Reynolds SJ, Kagaayi J, Gray RH, Clarke W, Chang LW, et al. The validity of self-reported antiretroviral use in persons living with HIV: a population-based study. AIDS. 2018;32(3):363–9.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Introduction of Prescription Oral Antivirals for COVID-19 to the Commercial Market. 2024. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/commercialcovid19oralantiviralsmemorevised20240220final.pdf

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the survey participants and Ipsos for completing survey

sampling and data collection.

Funding

This study was conducted as a collaboration between City University of New York (CUNY) and Pfizer. CUNY is the study sponsor. Pfizer, Inc. had no role in the collection, management, or analysis of the data; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kate Penrose contributed to the conceptualization and design of the analysis, conducted the statistical analysis, and drafted the original manuscript. Avantika Srivastava, Yanhan Shen, McKaylee M. Robertson, Sarah G. Kulkarni, Kristen E. Allen, Thomas M. Porter, Laura Puzniak, John M. McLaughlin, and Denis Nash contributed to the design of the analysis, interpretation of results, and reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Kristen E. Allen, Thomas M. Porter, Laura Puzniak and John M. McLaughlin are employees of Pfizer Inc. and hold stock and/or stock options of Pfizer Inc. Denis Nash discloses consulting fees from AbbVie and Gilead, and a research grant from Pfizer paid to his institution. Kate Penrose, Avantika Srivastava, Yanhan Shen, McKaylee M. Robertson, and Sarah G. Kulkarni report support from Pfizer through a research grant paid to their institution.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the City University of New York (CUNY IRB 2022-0407). The Institutional Review Board determined that the study met the criteria for Human Subject Research Exemption based on collection of de-identified survey data only. Consent to receive survey invitations from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel is obtained during the recruitment process. Before responding to a survey, individuals are reminded that their responses will be used for research purposes only and that they can choose not to participate or answer any question.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Penrose, K., Srivastava, A., Shen, Y. et al. Perceived Risk for Severe COVID-19 and Oral Antiviral Use Among Antiviral-Eligible US Adults. Infect Dis Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-01003-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-01003-3