Abstract

Introduction

Although patients with HBV have a risk of reactivation after immunosuppressive therapy (IST), the status of their risk management is unclear in Japan. This study aims to describe the proportion of patients who received preventive management of HBV reactivation during ISTs in patients with chronic HBV infection of HBsAg or resolved HBV infection.

Method

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using the JMDC Japanese claims database from April 2011 to June 2021. Patients with HBV infections of HbsAg who received ISTs or patients who had resolved HBV infections who received ISTs were identified from the database and evaluated for appropriate management to prevent HBV reactivation.

Results

In total, 6242 eligible patients were identified. The proportions of patients with appropriate HBV reactivation management, stratified by the HBV reactivation risk level of IST, was 43.1% (276/641) for high-risk, 40.2% (223/555) for intermediate-risk and 14.9% (741/4965) for low-risk patients. When the evaluation period for the outcome calculation was shortened from 360 to 180 days, the proportion for high risk increased to 52.7%. The odds ratios of large hospitals for receiving appropriate management were 2.16 (95% CI 1.12–4.44) in the high-risk, 4.63 (95% CI 2.34–10.25) in the intermediate-risk and 3.60 (95% CI 3.07–4.24) in the low-risk patients.

Conclusion

HBV reactivation management was tailored according to the reactivation risk associated with IST. However, adherence to HBV reactivation management guidelines was sub-optimal, even among high-risk patients. This is especially the case for ensuring smaller-sized medical institutions, highlighting the need for further educational activities.

Plain Language Summary

The study assesses the implementation of guideline-based management of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive therapy in Japan. The appropriate management of hepatitis B virus treatment involves prophylactic nucleos(t)ide analog (NUC) therapy and regular monitoring of hepatitis B virus DNA. This study aims to assess the extent to which these management practices are implemented in a clinical setting in Japan using a retrospective cohort study using the Japanese Medical Claims Database. The analysis identified 6242 eligible patients and identified whether they received appropriate management to prevent hepatitis B virus reactivation based on the level of risk associated with their immunosuppressive therapy. Based on the guidelines, the proportions of patients receiving appropriate reactivation management were 43.1% for high-risk, 40.2% for intermediate-risk and 14.9% for low-risk immunosuppressive therapy patients. Shortening the evaluation period from 360 to 180 days showed an increase in the proportion of high-risk patients to 52.7%, which indicated the potential challenge for continued monitoring after immunosuppressive therapy administration. The study shows that large hospitals present higher odds of patients receiving appropriate management. Overall, adherence to hepatitis B virus reactivation management guidelines was suboptimal, especially in smaller medical institutions, emphasizing the need for additional educational activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Patients with HBV have a risk of reactivation after immunosuppressive therapy (IST) but the status of their risk management is unclear in Japan. |

This study describes the proportion of patients who received preventive management of HBV reactivation during IST in patients with HBV infection of HBsAg or resolved HBV infection. |

What was learned from the study? |

From 6242 eligible patients, the proportions of patients receiving appropriate reactivation management were 43.1% for high-risk, 40.2% for intermediate-risk and 14.9% for low-risk IST patients. |

Shortening the evaluation period from 360 to 180 days showed an increase in the proportion of high-risk patients to 52.7%, which indicated the potential challenge for continued monitoring after IST administration. |

Adherence to HBV reactivation management guidelines was suboptimal, especially in smaller medical institutions, emphasizing the need for additional educational activities. |

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection can be reactivated after immunosuppressive therapy (IST) in both patients with chronic HBV infections of HBsAg and those who have recovered from HBV infections. Various studies have reported that HBV reactivation is associated with ISTs such as steroids, immunosuppressive agents [1, 2], anticancer agents [3, 4], molecular biological agents [5, 6], antirheumatic agents [7, 8], hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA) [9], immune checkpoint inhibitors [10, 11] and others.

Prophylactic management of HBV reactivation is critical because the mortality rate is extremely high [12] when hepatitis is triggered by HBV reactivation and progresses to fulminant hepatitis. The international community has recognized the significance of preventive management of HBV reactivation, and many countries have established management guidelines [13, 14]. One of the management standards is, for example, to ensure that the HBV DNA level remains below the standard threshold. If the HBV DNA level surpasses this threshold or if patients are HBs antigen positive, prophylactic nucleos(t)ide analog (NUC) therapy is advised.

In Japan, the research group led by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare released the initial guidelines for preventing HBV reactivation associated with ISTs treatments in 2009. The guideline was refined by the Japan Society of Hepatology (JSH) in 2013 [15]. The appropriateness of the HBV reactivation management presented in the guideline was corroborated by the multicenter prospective study on HBV reactivation during malignant lymphoma treatment with rituximab [16].

The development of the guidelines for management of HBV reactivation has advanced; however, adherence to them remains uncertain. Furthermore, deaths resulting from HBV reactivation are still being reported over a decade after the establishment of the JSH guidelines. Previous research underscored the low screening rate for HBV infection in patients receiving IST therapy [17, 18]. However, there are limited data regarding the current implementation status of preventive management of HBV reactivation in Japanese clinical settings.

Currently, various ISTs are available to patients, which has heightened awareness regarding the prophylactic management of HBV reactivation. In this context, this study aims to describe the proportion of patients who received preventive management of HBV reactivation during ISTs and to evaluate whether the management was implemented appropriately in a clinical setting in Japan, utilizing the Japanese administrative claims database.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

This retrospective cohort study utilized the Japanese administrative claims database provided by JMDC Inc. [19]. This nationwide database consolidates annual health check-up results along with claims data on insured employees and their dependents and encompasses information related to hospitalization and outpatient treatments. As of February 2022, the number of patients in the database was approximately 14 million. This database includes patient’s attributes (i.e., age and gender), medical facilities where they are treated, diagnoses, procedures and medications they received. Although data have been anonymized, individuals can be tracked across different hospitals using personal IDs if the same insurance covers them. While the database contains records of laboratory tests, it does not contain specific test results such as that for HBs antigen or a numerical value for HBV DNA levels.

The current study utilized data on patients diagnosed with HBV-related diseases between April 2011 and June 2021. It also required records of procedures for HBV-DNA tests available daily; however, in the JMDC database, it was only accessible from April 2012 onward. In this context, the start of the study period was set as April 2011, accounting for a 1-year look-back period to assess eligibility and covariates (as shown in the supplementary material, Figure S1).

Study Population

The study population consisted of patients with chronic HBV infections of HBsAg who received ISTs or patients who had resolved HBV infections who received ISTs. The study selected the population based on the records of the HBV-DNA tests. According to the JSH guidelines [15], prophylactic administration of NUCs is recommended after testing of HBs antigen and HBc or HBs antibodies prior to induction of IST, followed by HBVDNA testing if HBs antigen is positive (chronic HBV infections of HBsAg). In cases where HBc or HBs antibody tested positive (resolved HBV infections) when HBs antigen was negative, HBVDNA testing should be performed and prophylactic administration of NUCs is recommended when HBVDNA is ≥ 20 IU/ml. Monitoring of HBVDNA every 1–3 months is recommended when HBVDNA is < 20 IU/ml. Since the JMDC database lacks the results of laboratory tests for HBs antigen and HBs and HBc antibody, it was not possible to apply these criteria to identify the target population. However, patients with HBVDNA test history are expected to be positive for either HBs antigen or HBc antibody because HBV treatment and management in Japanese clinical practice strongly follows the JSH guidelines; the subjects in this study can consequently be selected based on the HBV-DNA test history. The study selected patients who were diagnosed with HBV-related diseases, had two or more HBV-DNA tests and underwent ISTs with immunosuppressive drugs, corticosteroids, anti-tumor drugs, anti-rheumatic drugs and antiviral drugs within the study period (April 2011–June 2021). The index date (Day 0) was defined as the first prescription date of an IST. Study patients were required to have data for at least 365 days before the index date to assess eligibility and covariates for the analyses. Relevant disease names, procedure names and drug names are described in the supplementary materials.

In the Japanese healthcare reimbursement system, claims for HBV-DNA tests are exclusive to patients previously confirmed as having chronic HBV infection of HBsAg, those who have recovered from HBV infections and those who were newly diagnosed with HBV infections. Because of the low incidence rate of new HBV infections in Japan, this test can be used as a proxy for the identification of patients who have either chronic HBV infections of HBsAg or have resolved HBV infections. For further enhancement of this specificity, the study included only patients who had two or more records of undergoing the HBV-DNA test.

This study excluded patients who met any of the following criteria: (1) diagnosed with HBV-related acute diseases (such as complicated acute hepatitis B, hepatic coma, fulminant hepatitis B, acute hepatitis B, subacute hepatitis, acute hepatitis, hepatitis B cirrhosis and fulminant hepatitis) between 365 days before the index date and the index date, (2) received NUC treatments between 365 and 90 days before the index date or (3) were < 18 years old at the index date. The design diagram of this study, list of diseases and IST are shown in the supplementary material (Figure S1, Table S1 and Table S2).

Study Outcomes

The eligible patients were evaluated for appropriate management to prevent HBV reactivation during the IST. The JSH guidelines suggest that patients are appropriately managed if they either: (1) undergo prophylactic NUC therapy or (2) have their HBV DNA levels regularly monitored [15]. This study defined recipients of prophylactic NUC treatments as those who received a prescription for any NUC medication, such as entecavir, tenofovir disoproxil, tenofovir alafenamide, lamivudine and adefovir pivoxil, between 90 days before the index and the index date. This definition is relevant for patients initiating an IST with non-steroid medications. However, for those starting IST that includes steroids, the time frame extends from 90 days before the index date to 7 days after the index date. Patients who received regular monitoring of HBV DNA levels were defined as those who had at least one HBV-DNA test in each quarter of a 360-day period, specifically during the intervals of days 0–90, 91–180, 181–270 and 271–360 (visual images are shown in the supplementary material, Figure S2).

The follow-up of the patients ended on the earliest of the following dates: 360 days after the index date, the date of death or departure from the insurance or the end of the study period (as of June 30, 2021).

Patients with a follow-up period < 360 days were deemed to have been regularly monitored for their HBV DNA levels if they underwent at least one HBV-DNA test per quarter during the period. Patients were considered censored if they did not receive prophylactic NUC therapy, had a follow-up period < 90 days and did not undergo an HBV DNA test until the end of the follow-up.

HBV Risk Classification of IST

The IST at the index date was classified according to the risk level of HBV reactivation (high risk, intermediate risk, low risk and risk uncertain) regarding the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) guideline [13]. The risk associated with ISTs using steroid medications was categorized based on the total dosage within a 30-day period from the index date. The therapies were considered high risk when patients received ≥ 560 mg steroids in total, intermediate risk when they received ≥ 300 mg but < 560 mg and low risk when they received < 300 mg within 30 days from the index date.

Furthermore, this study identified patient groups that received particularly high-risk ISTs. One group received treatments with rituximab and steroids within a week of the index date, and the other group was on the R-CHOP regimen, which administered rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunomycin), vincristine sulfate (Oncovin) and prednisolone.

Characteristics

This study also collected information on the medical institutions that the patients visited. This encompassed the institutions' management organizations (e.g., university hospitals, national and public hospitals, clinics and other hospitals) at index date, their classifications as either hospital (HP) or general practice (GP), whether they are hub hospital for cancer treatment and the number of beds. Furthermore, the study obtained information on the patient's age at the index date and gender diagnosed within a year preceding the index date.

Statistical Analysis

The study estimated the number and proportion of patients who received appropriate management to prevent HBV reactivation. The results were stratified based on the HBV reactivation risk classification associated with IST. For the sensitivity analysis, the evaluation period for the outcome calculation was shortened from 360 to 180 days. Additionally, the proportion was assessed for patient groups that received particularly high-risk ISTs, specifically the rituximab + steroid combination and the R-CHOP regimen.

This study calculated the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each characteristic variable using the univariate logistic regression model to identify the characteristics of patients with appropriate management to prevent HBV reactivation across each risk level of IST.

The study examined the annual trends in the proportion of patients who received appropriate management to prevent HBV reactivation from 2012 to 2021. Using an interrupted time series (ITS) analysis, it assessed whether the trend in the proportion of appropriate management shifted before and after the guideline revision in January 2013. The regression model was used to estimate the level change and trend change. The dependent variable was the proportion of appropriate management. The independent variables included an indicator representing before and after the guideline revision in January 2013, the time elapsed since April 2012, time elapsed since the January 2013 guideline revision and a quadratic term for the time elapsed (to account for non–linear time trend).

Data processing was executed using the Amazon Athena engine, version 3 (Amazon.com, Inc.), and statistical analyses were conducted using R, version 4.2.1 (The R Project for Statistical Computing).

Ethics

This study was conducted following the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki, respecting the ethical standards for research involving human participants.

This study did not require patient consent or approval from an institutional review board and independent ethics committee because the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects do not apply to studies exclusively on de-identified data.

Results

Patient Characteristics

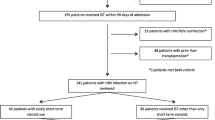

Between April 2011 and June 2021, 69,752 patients were diagnosed with HBV-related disease in the JMDC database. Of these, 6242 patients met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis (as detailed in Fig. 1). Table 1 presents the characteristics of the study population. The patient’s mean age was 53.01 (SD, 10.89) years old, and 55.8% were male. The mean follow-up period was 331.45 (SD, 75.11) days. In the classification of hepatitis B reactivation risk associated with ISTs, 10.3% of the patients were categorized as high risk, 8.9% as intermediate risk, 79.5% as low risk and 1.3% as risk uncertain.

At the start of IST, 59.6% of the patients had consulted a general practitioner (GP) at facilities with < 100 beds.

Proportion of Patients Who Received Appropriate Management to Prevent HBV Reactivation

Overall, 20.4% of the patients received appropriate management to prevent HBV reactivation. In the classification of HBV reactivation risk associated with IST, the high-risk group had the highest proportion at 43.1%. This was followed by the risk-uncertain group at 40.7%, the intermediate-risk group at 40.2% and the low-risk group, which had the lowest proportion at 14.9% (as detailed in Table 2).

Table 3a presents the results of the sensitivity analysis, where the evaluation period for the outcome was shortened from 360 to 180 days. With this adjusted outcome definition, the proportion in the high-risk group rose to 52.7%, an increase of nearly 10% compared to the primary outcome definition with a 360-day evaluation period. Furthermore, among the particularly high-risk populations receiving the combination of rituximab and steroids, the proportions were 53.4% for the primary outcome definition with a 360-day evaluation period compared to 63.1% with a 180-day evaluation period. For those receiving the R-CHOP regimen, the proportions were 55.2% and 70.7% for the 360-day and 180-day evaluations, respectively (results detailed in Table 3b).

Characteristics Associated with Appropriate Management for HBV Reactivation Prevention

Table 4 presents the results of the univariate logistic regression analyses for each group, classified by the HBV reactivation risk associated with IST. In the high-risk group, the odds ratio for appropriate management to prevent HBV reactivation at hospitals (HP) with ≥ 100 beds compared to general practitioners (GP) at facilities with < 100 beds was 2.16 (95% CI 1.12–4.44). In the intermediate-risk group, this odds ratio was 4.63 (95% CI 2.34–10.25), in the low-risk group it was 3.60 (95% CI 3.07–4.24), and in the risk-uncertain group, it was 1.92 (95% CI 0.63–6.63).

Time Trend of Appropriate Management for HBV Reactivation Prevention

The ITS analysis indicated no significant change in the trend of appropriate management to prevent HBV reactivation after January 2013, with a level change of − 0.88 (95% CI − 13.02 to 11.27) (refer to Fig. 2 and Table 5). The yearly trend in the proportion of appropriate management to prevent HBV reactivation from January 2012 to June 2021 is shown in Table 6, revealing an upward trend starting in 2017.

Discussion

This study found that in real-world clinical practice in Japan, the implementation of the management of HBV reactivation aligns with the risk level of IST. However, even in the high-risk IST group, < 50% of only a portion of the patients was provided with appropriate care per the HBV reactivation management guidelines, underscoring an evidence-practice gap. The proportion of appropriately managed cases was lower with a 1-year evaluation period compared to a 6-month period, which indicated the potential challenge for continued monitoring after IST administration, even for high-risk regimens such as R-CHOP. This finding indicates potential challenges in ensuring sufficient reactivation management beyond 6 months. Furthermore, the proportion of appropriate management was lower in smaller size medical institutions, which indicates a disparity in current practices based on the healthcare facility size. No change was observed in the proportion of HBV reactivation management in the 2013 revision of the JSH guidelines. However, an upward trend of the proportion was observed after 2017. This suggests that guideline updates should be paired with appropriate education activities.

A previous Japanese nationwide survey reported in 2008 showed a 22% incidence of fulminant hepatitis due to HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection; those with fulminant hepatitis had a 100% mortality rate [12]. Moreover, in a national survey reported in 2018, cases of acute liver failure due to HBV reactivation were still reported, and the mortality rate remains notably high [20]. These findings highlight the importance of managing HBV reactivation.

A previous study utilizing the Japanese claims database investigated the HBV screening rate among patients receiving chemotherapy for malignancies. It revealed that 66.3% of patients underwent HBs antigen testing before chemotherapy, while only 19.9% were tested for HBc/HBs antibody. This suggests an unsatisfactory HBV screening rate for patients with cancer scheduled for chemotherapy [17]. While the previous studies raised issues about screening rates, the status of HBV reactivation management was not described. Our current research pinpoints unmet needs in HBV reactivation prevention by showcasing real-world clinical management practices. Notably, the scope of the current study is broader as it includes not only patients with malignancies but also those undergoing immune suppression for diseases other than malignancies in patient with HBV infections of HBsAg or those with resolved HBV infections. Additionally, this study included ISTs that incorporated steroids. Given that steroids are prevalently utilized in immunotherapy and have been documented to induce HBV DNA, establishing the management practices for patients on such treatments is deemed invaluable.

In Japan, the guidelines for preventing HBV reactivation during IST were first introduced in 2009 and have subsequently been revised. This context indicates a growing awareness of high-risk IST, which has established a trend in our study toward implementing HBV reactivation management for high-risk IST groups. Notably, professional organizations such as the Japanese Society of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery have incorporated details on HBV reactivation management in their recent guideline updates. The uptick in HBV reactivation management post-2017 in our study may be influenced, at least partially, by the directives of these pertinent professional societies.

The JSH guidelines recommend monitoring HBV DNA levels during immunosuppressive therapy and for at least 6 months following any treatment modifications, including discontinuation. For the regimens involving high-risk drugs such as rituximab, a 12-month monitoring period is required. However, one of the findings of this study reveals that the reactivation management for R-CHOP regimens was not sustained adequately beyond the 6-month post-treatment mark. These results suggest that, despite existing awareness regarding reactivation management, there might be a tendency to underestimate its long-term significance, particularly following treatment adjustments or cessation.

The results of this study indicated that reactivation management was more commonly implemented in HP than in GP across all risk levels of IST, implying that reactivation management awareness may differ depending on the size of the medical facility. This finding may help in designing communication in practice.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the JMDC database lacks data on antigen and antibody test results. Consequently, this study determines the presence of chronic HBV infections of HBsAg or resolved infections based on HBV DNA testing records. This divergence between database records and clinical criteria prevents differentiation between chronic and resolved HBV infection, leaving the distribution of both conditions within the study population unclear. Consequently, while the HBV reactivation risk associated with some ISTs varies depending on whether the patient has a chronic HBV infection of HBsAg or a resolved infection, this study classifies risk based solely on the type of IST used. Nonetheless, within the Japanese healthcare framework, billing for HBV DNA tests is permitted exclusively for individuals confirmed as having chronic HBV infections of HBsAg or those with a history of HBV infection. Thus, patients documented as having undergone HBV DNA testing are likely to have a high specificity for having chronic HBV infections of HBsAg or for having had resolved HBV infections, though sensitivity of this approach may be limited. To further bolster this specificity, this study incorporated patients recorded as having the test on two or more separate occasions. Second, this study did not include data on patients aged ≥ 75 years. The JMDC database draws from corporate health insurance association data, which mainly encompasses information about company-employed individuals and their families. Therefore, there are limitations to generalizing the findings of this study to the broader elderly population. Third, due to the descriptive approach of this study, it applied a univariate logistic regression model to assess the characteristics associated with receiving HBV reactivation management. As covariates were not adjusted for, the findings of this study should not be construed as indicating causal relationships.

In light of the findings in this study, it is clear that enhanced awareness campaigns about HBV reactivation are essential in the current clinical landscape, especially considering the diverse array of ISTs available. Recent revisions in guidelines by relevant professional societies have contributed to an increase in the adoption of reactivation management. Continued awareness campaigns are therefore imperative to increase adoption. Also, emphasizing the importance of maintaining reactivation management and elevating awareness among general practitioners (GPs) is crucial.

Our findings underscore the unmet needs in HBV reactivation management; however, several aspects remain unexplored. While individualized management grounded in risk stratification is essential for HBV reactivation, limited studies have yet to separately investigate the actual practices for screening and managing patients with chronic HBV infection of HBsAg and those with resolved HBV infections. Furthermore, the impact of these screenings and management protocols on improving outcomes, particularly HBV reactivation, has not been examined. Further research is warranted to explore these issues.

Conclusions

This study assessed the management of HBV reactivation during IST in patients with either chronic HBV infection of HBsAg or resolved HBV infection. It revealed that HBV reactivation management was tailored according to the reactivation risk associated with IST. However, adherence to HBV reactivation management guidelines was sub-optimal, even among high-risk patients. While these management strategies were implemented for 6 months, consistent application over a year was lacking. Moreover, management practices varied based on the size of healthcare facilities.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the research contracts with the data suppliers.

References

Lubel JS, Angus PW. Hepatitis B reactivation in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy: diagnosis and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(5):864–71.

Wursthorn K, Wedemeyer H, Manns MP. Managing HBV in patients with impaired immunity. Gut. 2010;59(10):1430–45.

Lok AS, Liang RH, Chiu EK, Wong KL, Chan TK, Todd D. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy. Report of a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(1):182–8.

Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, Ho WM, Steinberg JL, Tam JS, et al. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol. 2000;62(3):299–307.

Lubel JS, Testro AG, Angus PW. Hepatitis B virus reactivation following immunosuppressive therapy: guidelines for prevention and management. Intern Med J. 2007;37(10):705–12.

Carroll MB, Forgione MA. Use of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients: a literature review and potential mechanisms of action. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(9):1021–9.

Urata Y, Uesato R, Tanaka D, Kowatari K, Nitobe T, Nakamura Y, et al. Prevalence of reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Mod Rheumatol. 2011;21(1):16–23.

Hong X, Xiao Y, Xu L, Liu L, Mo H, Mo H. Risk of hepatitis B reactivation in HBsAg-/HBcAb+ patients after biologic or JAK inhibitor therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023;11(2): e780.

Aggeletopoulou I, Konstantakis C, Manolakopoulos S, Triantos C. Risk of hepatitis B reactivation in patients treated with direct-acting antivirals for hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(24):4317–23.

Xia Z, Zhang J, Chen W, Zhou H, Du D, Zhu K, et al. Hepatitis B reactivation in cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2023;12(1):87.

Hagiwara S, Nishida N, Ida H, Ueshima K, Minami Y, Takita M, et al. Clinical implication of immune checkpoint inhibitor on the chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatol Res. 2022;52(9):754–61.

Umemura T, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K, Kumada H, Japan de novo Hepatitis B Research Group. Mortality secondary to fulminant hepatic failure in patients with prior resolution of hepatitis B virus infection in Japan. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(5):e52–6.

Lau G, Yu ML, Wong G, Thompson A, Ghazinian H, Hou JL, et al. Correction to: APASL clinical practice guideline on hepatitis B reactivation related to the use of immunosuppressive therapy. Hepatol Int. 2022;16(2):486–7.

Wang Y, Han SHB. Hepatitis B reactivation: a review of clinical guidelines. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55(5):393–9.

Drafting Committee for Hepatitis Management Guidelines, the Japan Society of Hepatology. Japan Society of Hepatology Guidelines for the management of hepatitis B virus infection: 2019update. Hepatol Res. 2020;50(8):892–923.

Kusumoto S, Tanaka Y, Suzuki R, Watanabe T, Nakata M, Takasaki H, et al. Monitoring of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA and risk of HBV reactivation in B-cell lymphoma: a prospective observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):719–29.

Ikeda M, Yamamoto H, Kaneko M, Oshima H, Takahashi H, Umemoto K, et al. Screening rate for hepatitis B virus infection in patients undergoing chemotherapy in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21(6):1162–6.

Watanabe R, Ishii T, Kobayashi H, Asahina I, Takemori H, Izumiyama T, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in patients with rheumatic diseases in Tohoku area: a retrospective multicenter survey. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2014;233(2):129–33.

Nagai K, Tanaka T, Kodaira N, Kimura S, Takahashi Y, Nakayama T. Data resource profile: JMDC claims database sourced from health insurance societies. J Gen Fam Med. 2021;22(3):118–27.

Nakao M, Nakayama N, Uchida Y, Tomiya T, Ido A, Sakaida I, et al. Nationwide survey for acute liver failure and late-onset hepatic failure in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(6):752–69.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

The authors express their gratitude to Dr. Paola Sanoni from Datack, Inc. for editorial assistance and medical writing support and Mr. Kyosuke Kimura from Datack, Inc., for his contribution to the investigation. Support for this assistance was funded by Datack, Inc.

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service fee was funded by Gilead Sciences K.K., Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception (Yasuhito Tanaka), study design (Yasuhito Tanaka, Daisuke Nakamoto, Yi Piao, Hajime Mizutani, Yoshiyuki Saito, Kyung min Kwon, Harriet Dickinson), methodology (Yoshiyuki Saito), literature review (Daisuke Nakamoto), data analysis (Ryozo Wakabayashi), discussion of results (Yasuhito Tanaka, Daisuke Nakamoto, Yi Piao, Hajime Mizutani, Yoshiyuki Saito, Kyung min Kwon, Harriet Dickinson), manuscript drafting (Ryozo Wakabayashi).

All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Yasuhito Tanaka received honoraria from Gilead Sciences Inc., AbbVie GK., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., ASKA Pharmaceutical Holdings Co., Ltd., OTSUKA Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline PLC., and GlaxoSmithKline PLC.; research funding from Gilead Sciences, Inc., AbbVie GK., FUJIREBIO Inc., Sysmex Corp., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K. and GlaxoSmithKline PLC. Daisuke Nakamoto, Yi Piao, Hajime Mizutani, Kyung min Kwon, and Harriet Dickinson are current employees of Gilead Sciences with stock ownership. Yoshiyuki Saito is a board member of Datack Inc. with stock ownership.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted following the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki, respecting the ethical standards for research involving human participants. This study did not require patient consent or approval from an institutional review board and independent ethics committee because the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects do not apply to studies exclusively on de-identified data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, Y., Nakamoto, D., Piao, Y. et al. Implementation of Guideline-Based HBV Reactivation Management in Patients with Chronic HBV Infections of HBsAg or Resolved HBV Infection Undergoing Immunosuppressive Therapy. Infect Dis Ther 13, 1607–1620 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-00997-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-024-00997-0