Abstract

Introduction

Intra-abdominal infections represent the second most frequently acquired infection in the intensive care unit (ICU), with mortality rates ranging from 20% to 50%. Candida spp. may be responsible for up to 10–30% of cases. This study assesses risk factors for development of intra-abdominal candidiasis (IAC) among patients admitted to ICU.

Methods

We performed a case–control study in 26 European ICUs during the period January 2015–December 2016. Patients at least 18 years old who developed an episode of microbiologically documented IAC during their stay in the ICU (at least 48 h after admission) served as the case cohort. The control group consisted of adult patients who did not develop episodes of IAC during ICU admission. Matching was performed at a ratio of 1:1 according to time at risk (i.e. controls had to have at least the same length of ICU stay as their matched cases prior to IAC onset), ICU ward and period of study.

Results

During the study period, 101 case patients with a diagnosis of IAC were included in the study. On univariate analysis, severe hepatic failure, prior receipt of antibiotics, prior receipt of parenteral nutrition, abdominal drain, prior bacterial infection, anastomotic leakage, recurrent gastrointestinal perforation, prior receipt of antifungal drugs and higher median number of abdominal surgical interventions were associated with IAC development. On multivariate analysis, recurrent gastrointestinal perforation (OR 13.90; 95% CI 2.65–72.82, p = 0.002), anastomotic leakage (OR 6.61; 95% CI 1.98–21.99, p = 0.002), abdominal drain (OR 6.58; 95% CI 1.73–25.06, p = 0.006), prior receipt of antifungal drugs (OR 4.26; 95% CI 1.04–17.46, p = 0.04) or antibiotics (OR 3.78; 95% CI 1.32–10.52, p = 0.01) were independently associated with IAC.

Conclusions

Gastrointestinal perforation, anastomotic leakage, abdominal drain and prior receipt of antifungals or antibiotics may help to identify critically ill patients with higher probability of developing IAC. Prospective studies are needed to identify which patients will benefit from early antifungal treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intra-abdominal infections represent the second most frequently acquired infection in the intensive care unit, with mortality rates ranging from 20% to 50%. |

Candida spp. may be responsible for up to 10–30% of cases. |

Recurrent gastrointestinal perforation, anastomotic leakage and prior antibiotic therapy have been identified as risk factors for developing intra-abdominal candidiasis. |

Prospective clinical studies are needed to identify which patients will benefit from early antifungal treatment. |

Introduction

Intra-abdominal infections represent the second most frequently acquired infection in the intensive care unit (ICU) [1, 2], with mortality rates ranging from 20% to 50% [1, 3,4,5]. They are more often caused by hospital isolates such as Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa or enterococci, but Candida spp. may be responsible for up to 10–30% of cases [1, 6, 7].

Although Candida spp. is increasingly recognized as a non-negligible cause of ICU-acquired intra-abdominal infection [4, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14], risk factors for developing an intra-abdominal candidiasis (IAC) in ICU patients are poorly understood [15, 16]. To the best of our knowledge, data on this disease are limited, fragmented, and usually consist of small collections of cases from single institutions [15,16,17]. Consequently, the characteristics of patients in whom there could be an increased risk of IAC and that may benefit the most from empiric antifungal therapy had still to be clearly identified [18,19,20,21].

The aim of the present multicentre, multinational, case–control study, conducted within the EUCANDICU project [22], was to assess independent risk factors for ICU-acquired IAC.

Methods

This study was a retrospective, matched case–control study conducted to identify risk factors associated with IAC in ICU patients. Cases were identified via databases maintained by the microbiology laboratories of 26 ICUs from 25 large tertiary care European hospitals (12 in Italy, 5 in France, 2 in Greece, 1 in Belgium, 1 in Czech Republic, 1 in Germany, 1 in Ireland, 1 in Portugal, 1 in Spain, and 1 in the Netherlands). Twenty of the 26 centres (77%) were also included in a previous paper within the EUCANDICU project, detailing the incidence of invasive candidiasis in ICU (see supplementary material for more information) [22]. The primary study endpoint was development of ICU-acquired IAC.

Cases of IAC and controls were eligible for inclusion in the present study if they had an ICU stay of 48 h or longer and were admitted to the ICU from January 2015 to December 2016. Exclusion criteria were (i) age less than 18 years; (ii) receiving a diagnosis of invasive candidiasis prior to 48 h of the ICU stay or (iii) had concomitant intra-abdominal bacterial infections. During the study period surveillance swab screening was not a routine procedure in most of the ICU included in the study.

Patients who developed an episode of microbiologically documented IAC after at least 48 h of ICU stay were defined as cases. Each case patient was included only once, at the time of the first IAC episode, even if more than one episode was reported. The control group consisted of patients admitted to ICU for more than 48 h.

Matched controls (cases to control ratio 1:1) were selected by local investigators for each case. Matching criteria included ICU ward and time at risk for developing IAC (i.e. time from ICU admission to IAC development in each case was matched to a length of ICU stay at least equal to the corresponding control). Control patients were selected for case patients using the following mechanism: we determined the length of ICU stay prior to the development of IAC for a given case patient, restricted the roster of ICU patients to those who had lengths of stay at least as long as the case patient’s time to infection, and then selected one control patient per case patient matching according to the same ICU and the same period. Most controls remained hospitalized in ICU after their inclusion in the study and they were followed up to ensure that (i) they did not develop subsequent episodes of invasive candidiasis based on negative cultures and (ii) did not receive any antifungal drugs during their remaining hospitalization.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the coordinating center (Regional Ethics Committee of Friuli-Venezia-Giulia Region, registry number CEUR-2017-Os-033-ASUIUD). Owing to its retrospective nature written informed consent was deemed unnecessary.

Data Collection

Investigators at each centre used a structured digital data collection instrument to retrieve clinical and laboratory data from the patients’ medical records.

Risk factors were collected starting from 30 days prior to IAC diagnosis and included corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs; acute kidney injury or need for renal replacement therapy; presence of a central venous catheter (CVC); invasive mechanical ventilation; receipt of antibiotics or antifungal drugs (being on antibiotic or antifungal treatment prior to IAC, for at least 7 days); parenteral nutrition; any bacterial infection; colonization of Candida at multiple non-sterile sites (i.e. sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage, urine, feces and other non-sterile sites); major abdominal surgery; number of abdominal surgical interventions performed; recurrent gastrointestinal perforation; anastomotic leakage and abdominal drain. Other variables collected included demographics, comorbidities (also collectively expressed on the basis of the Charlson comorbidity index [23]), type of ICU ward (medical, surgical or mixed ICU); severity of illness at the time of ICU admission reflected by the SOFA score.

Definitions

ICU-acquired IAC was defined as an episode of IAC developing at least 48 h after ICU admission. IAC was defined according to previously published definitions [20, 24]. More specifically, IAC was defined as the presence of at least one of the following: (i) Candida detection by direct microscopy or growth in culture from necrotic or purulent intra-abdominal specimens obtained by percutaneous aspiration or during surgery; (ii) growth of Candida from bile or intra-biliary duct devices, or from abdominal organs biopsies; (iii) growth of Candida from blood cultures in the presence of secondary or tertiary peritonitis in the absence of other pathogens; (iv) growth of Candida from drainage tubes inserted less than 24 h before culture sampling [20]. Severe hepatic failure was defined as a prior history of Child B and C liver cirrhosis.

Microbiological Studies

Candida species identification and in vitro antifungal activity were assessed at participating hospitals using local routine methods and clinical breakpoints of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) [www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints], respectively.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis was aimed at the identification of predictors of ICU-acquired IAC. To this aim, the possible difference of categorical and continuous variables with development of IAC was tested by means of the chi-squared (χ2) and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, respectively. Subsequently, variables associated with the development of intra-abdominal candidiasis in univariable comparisons (p < 0.20) were included in a multivariable, conditional logistic regression model for matched pairs (with the strata being composed of pairs of a case plus their control [25]) and further selected for the final multivariable model using a stepwise backward procedure. The analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

During the study period, 101 case patients with a diagnosis of IAC were included in the study. Of those, only seven patients (6.9%) had a concomitant blood cultures positive for Candida spp. The most commonly isolated species was Candida albicans (58.4% of the isolates), followed by Candida glabrata (15.8%) and Candida tropicalis (4.0%). Other Candida species accounted for 5% of the isolates (Candida krusei 3.0%, Candida dubliniensis 1%, other 1%). The remaining 16.8% of cases had more than one Candida species isolated. Overall, resistance to fluconazole was detected in 17 out of 64 tested isolates (26.5%).

Demographics, Clinical Characteristics and Risk Factors for Intra-Abdominal Candidiasis

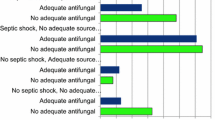

Table 1 shows the results of the univariate analysis of predictors of IAC. Variables associated with IAC included severe hepatic failure (7.9% vs. 1.0% in cases and controls, respectively, p = 0.03), prior receipt of antibiotics (69.3% vs. 41.6%, p = 0.0001), parenteral nutrition (64.4% vs. 48.5%, p = 0.03), abdominal drain (60.4% vs. 39.6%, p = 0.005), prior bacterial infection (53.5% vs. 20.8%, p = 0.001), anastomotic leakage (45.3% vs. 20.5%, p = 0.007), recurrent gastrointestinal perforation (31.4% vs. 6.8%, p = 0.002), prior receipt of antifungals (26.7% vs. 12.9%, p = 0.02) and higher median number of abdominal surgical interventions (median surgical interventions 3 vs. 1, p = 0.04). Controls had more frequently a prior history of heart disease (20.8% vs. 36.6%, p = 0.02) and neurological disease (5.9% vs. 16.8%, p = 0.02).

Multivariate Analysis

Table 2 shows the results from the multivariate analysis. The following factors remained independently associated with IAC: recurrent gastrointestinal perforation (OR 13.90; 95% CI 2.65–72.82, p = 0.002), anastomotic leakage (OR 6.61; 95% CI 1.98–21.99, p = 0.002), abdominal drain (OR 6.58; 95% CI 1.73–25.06, p = 0.006) and prior receipt of antifungal drugs (OR 4.26; 95% CI 1.04–17.46, p = 0.04) or antibiotics (OR 3.78; 95% CI 1.32–10.52, p = 0.01).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the largest to evaluate independent risk factors for developing intra-abdominal candidiasis in a large population of patients admitted to ICU. We found that recurrent gastrointestinal perforation, anastomotic leakage, abdominal drain and receipt of antifungal drugs or antibiotics for more than 7 days were independently associated with the development of IAC.

An important increase in Candida spp. among the pathogens involved in intra-abdominal infections has been reported in the last decade [8,9,10,11]. Candida is currently one of the most important causative agent of intra-abdominal infection, because of its reported association with increased morbidity and mortality [4, 8,9,10,11,12, 20, 24]. In some reports, Candida accounts for more than 50% of all isolated pathogens occurring in intra-abdominal infection in ICU [4, 8,9,10,11,12], and ranks as the second to fourth most common microorganism in several intra-abdominal infection series [8,9,10,11].

Unfortunately, our understanding of risk factors associated with IAC had been mostly extrapolated from studies including patients with candidemia or from patients with non-postoperative intra-abdominal infections [15,16,17], a population mainly coming from the community, with unique characteristics that may not be relevant to critically ill patients with prolonged ICU stay, who are those in whom IAC mostly develops. These studies showed that length of stay before surgery, peroperative cardiovascular failure, generalized peritonitis, upper gastrointestinal tract perforation, Candida colonization or number of organ dysfunctions were associated with Candida isolation in the abdomen [15,16,17].

The present study is a better reflection of daily clinical practice because we included only patients admitted to ICU, which corresponds to the largest proportion of patients affected by IAC [26,27,28]. In our report, variables independently associated with IAC were recurrent gastrointestinal perforation, anastomotic leakage, abdominal drain and prior antifungal drugs or antibiotics more than 7 days. The association with recurrent gastrointestinal perforation or anastomotic leakage was not unexpected. Indeed, both factors cause gastrointestinal barrier destruction and create a permissive environment that allows the seeding of Candida cells into the peritoneal cavity [20, 29]. Therefore, our findings support previous recommendation to consider an antifungal treatment for patients with recent abdominal surgery and recurrent gastrointestinal perforation or anastomotic leakage [13, 20].

The presence of abdominal drain was also associated with a higher probability of developing IAC in patients admitted to the ICU. In this study, the management of abdominal devices was left to the operating surgeon’s discretion and no protocol was available indicating the conditions for using them. Ours is the first study to show this association. We could speculate that a foreign material in a contaminate field might be a “culture medium” for Candida, supporting the onset of postoperative IAC. In addition, yeasts are typically associated with the ability to form biofilms on implanted devices [30, 31], suggesting that Candida spp. may be associated with IAC development caused by formation of biofilm on prosthetic devices. However, in order to give a definitive conclusion, future studies are recommended.

We also found that prior exposure to antibiotics was an independent risk factors for IAC in ICU patients [15]. Our results are consistent with several earlier studies in which exposure to antibiotic agents was strongly associated with invasive candidiasis [32,33,34]. The prolonged use of antibiotics could create a selective pressure for the overgrowth and endurance of Candida in the gut, which could increase the likelihood of subsequent IAC development [35,36,37]. Further studies should clarify the relationships between the spectrum of antimicrobial activity and the duration of previous antibiotic use with IAC development. Moreover, the independent association between previous antifungal drugs and subsequent development of IAC may reflect the severity of patients’ underlying diseases.

In the absence of clinical evidence supporting the systematic benefit of antifungal prophylaxis [38,39,40], other strategies to decrease rates of IAC should be considered. On the basis of our findings, attempts aimed at implementing adequate surgical procedures and supportive therapies may have a higher impact on reducing episodes of IAC in ICU [41]. Moreover, previous studies have shown a decrease of invasive candidiasis by improving antimicrobial stewardship strategies and/or infection control measures [42, 43]. Therefore, audits of the use of antimicrobial agents should be considered for understanding the real need for antibiotics and guide their judicious use, especially in the presence of other risk factors for IAC.

In contrast to previous studies, we could not demonstrate that Candida colonization was a risk factor for IAC [2, 17]. However, this could be explained by the policy of some centres included in the EUCANDICU study to not actively and systematically screen for Candida carriers in all patients admitted to ICU. This represents a clear limitation of the present observational study.

As for etiology of IAC in terms of the relative prevalence of the different Candida species, information remains partially elusive [20, 44]. In our study, which mainly includes centres from southern European regions, we observed the typical distribution of Candida species of this geographical area, where C. albicans is predominant, followed by Candida parapsilosis and C. glabrata [45, 46]. Of interest, fluconazole-non-susceptible strains occurred in about a quarter of tested strains. This finding may have important implications for the selection of empirical antifungal therapy among patients with IAC hospitalized in European ICUs.

There are several potential limitations to our study that should be addressed. First, selection bias is normally of concern in a case–control study; however, cases and controls were selected from the same distinct source cohort (ICU admission), thus minimizing the likelihood of selection bias. Second, we were not able to recruit more than one control patient per case, thus limiting the statistical power of the present study; however, this limitation reflects the “real life” difficulty to identify patients admitted to ICU who surely develop no invasive candidiasis. Third, although the EUCANDICU study is a multicentre study including a large number of patients, the generalizability of the observations may be limited by differences in Candida epidemiology between geographical areas or by differences in medical practice or health system organization. Nevertheless, these data are important, because they reflect the most robust series of patients with ICU-acquired IAC in a large group of centres coming from several European countries. Fourth, the study population gathers together different clinical situations such as secondary or tertiary peritonitis, abdominal abscess, cholangitis, cholecystitis and infected pancreatic necrosis [47] that were not differentiated in our study. Accordingly, future studies should aim for a homogenous cohort of patients to more closely address the risk factor issue of this complex population. Fifth, other unmeasured factors such as previous antibiotic exact duration or reasons for previous antibiotic treatment (complicated intra-abdominal infections versus other reasons) might have significantly contributed to development of intra-abdominal candidiasis. In addition, we could not control for the type of abdominal surgery performed or the precise location of perforation or leakage, factors that have been previously shown to be associated with the frequency of Candida isolation in abdominal fluid samples (gastroduodenal, small intestine, biliary tract). Lastly, another limitation of our study is the lack of data regarding fungal biomarkers or comprehensive information regarding prior Candida colonization and the inherent possibility of having missed some cases of IAC. Therefore, our results cannot be considered as definitive but rather as a starting point to justify costlier and time-consuming longitudinal studies in the near future.

Conclusions

On the basis of these findings, recurrent gastrointestinal perforation or anastomotic leakage in addition to prior antibiotic therapy may help clinicians to identify a subgroup of critically ill patients with higher probability of developing intra-abdominal candidiasis. A large multicentre study is needed to prospectively and externally validate our findings, and to potentially create a dedicated prediction score to better identify patients at risk of ICU-acquired IAC.

References

De Waele J, Lipman J, Sakr Y, et al. Abdominal infections in the intensive care unit: characteristics, treatment and determinants of outcome. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:420. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-420.

Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302(21):2323–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.1754.

Finfer S, Bellomo R, Lipman J, French C, Dobb G, Myburgh J. Adult-population incidence of severe sepsis in Australian and New Zealand intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(4):589–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-004-2157-0.

Montravers P, Mira JP, Gangneux JP, Leroy O, Lortholary O, AmarCand Study Group. A multicentre study of antifungal strategies and outcome of Candida spp. peritonitis in intensive-care units. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(7):1061–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03360.x.

Blot S, Antonelli M, Arvaniti K, et al. Epidemiology of intra-abdominal infection and sepsis in critically ill patients: “AbSeS”, a multinational observational cohort study and ESICM Trials Group Project. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(12):1703–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-019-05819-3.

Augustin P, Kermarrec N, Muller-Serieys C, et al. Risk factors for multidrug resistant bacteria and optimization of empirical antibiotic therapy in postoperative peritonitis. Crit Care. 2010;14(1):R20. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc8877.

Bassetti M, Castaldo N, Cattelan A, et al. Ceftolozane/tazobactam for the treatment of serious Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: a multicentre nationwide clinical experience. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019;53(4):408–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.11.001.

Sartelli M, Catena F, Ansaloni L, et al. Complicated intra-abdominal infections worldwide: the definitive data of the CIAOW Study. World J Emerg Surg. 2014;9:37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-7922-9-37.

de Ruiter J, Weel J, Manusama E, Kingma WP, van der Voort PH. The epidemiology of intra-abdominal flora in critically ill patients with secondary and tertiary abdominal sepsis. Infection. 2009;37(6):522–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-009-8249-6.

Sandven P, Qvist H, Skovlund E, Giercksky KE, NORGAS Group, the Norwegian Yeast Study Group. Significance of Candida recovered from intraoperative specimens in patients with intra-abdominal perforations. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(3):541–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-200203000-00008.

Montravers P, Dupont H, Gauzit R, et al. Candida as a risk factor for mortality in peritonitis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):646–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000201889.39443.D2.

Klingspor L, Tortorano AM, Peman J, et al. Invasive Candida infections in surgical patients in intensive care units: a prospective, multicentre survey initiated by the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) (2006–2008). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(1):87e1–e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2014.08.011.

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(4):e1-50. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ933.

Chou EH, Mann S, Hsu TC, et al. Incidence, trends, and outcomes of infection sites among hospitalizations of sepsis: a nationwide study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1): e0227752. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227752.

Dupont H, Bourichon A, Paugam-Burtz C, Mantz J, Desmonts JM. Can yeast isolation in peritoneal fluid be predicted in intensive care unit patients with peritonitis? Crit Care Med. 2003;31(3):752–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000053525.49267.77.

Dupont H, Guilbart M, Ntouba A, et al. Can yeast isolation be predicted in complicated secondary non-postoperative intra-abdominal infections? Crit Care. 2015;19:60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-0790-3.

Xia R, Wang D. Risk factors of invasive candidiasis in critical cancer patients after various gastrointestinal surgeries: a 4-year retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(44): e17704. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000017704.

Parkins MD, Sabuda DM, Elsayed S, Laupland KB. Adequacy of empirical antifungal therapy and effect on outcome among patients with invasive Candida species infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(3):613–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkm212.

Valerio M, Rodriguez-Gonzalez CG, Munoz P, et al. Evaluation of antifungal use in a tertiary care institution: antifungal stewardship urgently needed. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(7):1993–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dku053.

Bassetti M, Righi E, Ansaldi F, et al. A multicenter multinational study of abdominal candidiasis: epidemiology, outcomes and predictors of mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(9):1601–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3866-2.

Yan T, Li SL, Ou HL, Zhu SN, Huang L, Wang DX. Appropriate source control and antifungal therapy are associated with improved survival in critically ill surgical patients with intra-abdominal candidiasis. World J Surg. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05380-x.

Bassetti M, Giacobbe DR, Vena A, et al. Incidence and outcome of invasive candidiasis in intensive care units (ICUs) in Europe: results of the EUCANDICU project. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):219. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2497-3.

Charlson M, Szatrowski TP, Peterson J, Gold J. Validation of a combined comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(11):1245–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)90129-5.

Bassetti M, Marchetti M, Chakrabarti A, et al. A research agenda on the management of intra-abdominal candidiasis: results from a consensus of multinational experts. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(12):2092–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-3109-3.

Hosmer DW LS, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

Sganga G, Wang M, Capparella MR, et al. Evaluation of anidulafungin in the treatment of intra-abdominal candidiasis: a pooled analysis of patient-level data from 5 prospective studies. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38(10):1849–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-019-03617-9.

Bassetti M, Peghin M, Carnelutti A, et al. Clinical characteristics and predictors of mortality in cirrhotic patients with candidemia and intra-abdominal candidiasis: a multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(4):509–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4717-0.

Lagunes L, Rey-Perez A. What s new in intraabdominal candidiasis in critically ill patients, a review. Hosp Pract (1995). 2019;47(4):171–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548331.2019.1677032.

Peman J, Aguilar G, Valia JC, et al. Javea consensus guidelines for the treatment of Candida peritonitis and other intra-abdominal fungal infections in non-neutropenic critically ill adult patients. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2017;34(3):130–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riam.2016.12.001.

Munoz P, Agnelli C, Guinea J, et al. Is biofilm production a prognostic marker in adults with candidaemia? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(9):1010–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.022.

Munoz P, Vena A, Valerio M, et al. Risk factors for late recurrent candidaemia. A retrospective matched case-control study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(3):277e11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2015.10.023.

Jensen JU, Hein L, Lundgren B, et al. Invasive Candida infections and the harm from antibacterial drugs in critically ill patients: data from a randomized, controlled trial to determine the role of ciprofloxacin, piperacillin-tazobactam, meropenem, and cefuroxime. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):594–602. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000000746.

Zaoutis TE, Prasad PA, Localio AR, et al. Risk factors and predictors for candidemia in pediatric intensive care unit patients: implications for prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(5):e38-45. https://doi.org/10.1086/655698.

Dudoignon E, Alanio A, Anstey J, et al. Outcome and potentially modifiable risk factors for candidemia in critically ill burns patients: a matched cohort study. Mycoses. 2019;62(3):237–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/myc.12872.

Rashid MU, Weintraub A, Nord CE. Effect of new antimicrobial agents on the ecological balance of human microflora. Anaerobe. 2012;18(2):249–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.11.005.

Mayer FL, Wilson D, Hube B. Candida albicans pathogenicity mechanisms. Virulence. 2013;4(2):119–28. https://doi.org/10.4161/viru.22913.

Cole GT, Halawa AA, Anaissie EJ. The role of the gastrointestinal tract in hematogenous candidiasis: from the laboratory to the bedside. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(Suppl 2):S73-88. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/22.supplement_2.s73.

Eggimann P, Francioli P, Bille J, et al. Fluconazole prophylaxis prevents intra-abdominal candidiasis in high-risk surgical patients. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(6):1066–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-199906000-00019.

Senn L, Eggimann P, Ksontini R, et al. Caspofungin for prevention of intra-abdominal candidiasis in high-risk surgical patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(5):903–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-009-1405-8.

Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Shoham S, Vazquez J, et al. MSG-01: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of caspofungin prophylaxis followed by preemptive therapy for invasive candidiasis in high-risk adults in the critical care setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(9):1219–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu074.

Vena A, Bouza E, Valerio M, et al. Candidemia in non-ICU surgical wards: comparison with medical wards. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10): e0185339. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185339.

Molina J, Penalva G, Gil-Navarro MV, et al. Long-term impact of an educational antimicrobial stewardship program on hospital-acquired candidemia and multidrug-resistant bloodstream infections: a quasi-experimental study of interrupted time-series analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(12):1992–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix692.

Martin-Gutierrez G, Penalva G, Ruiz-Perez de Pipaon M, et al. Efficacy and safety of a comprehensive educational antimicrobial stewardship program focused on antifungal use. J Infect. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2020.01.002.

Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Righi E, Merelli M, Bassetti M. Elderly versus non-elderly patients with intra-abdominal candidiasis in the ICU. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017;83(11):1126–36. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0375-9393.17.11528-2.

Vena A, Bouza E, Corisco R, et al. Efficacy of a “checklist” intervention bundle on the clinical outcome of patients with candida bloodstream infections: a quasi-experimental pre-post study. Infect Dis Ther. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-020-00281-x.

Cardozo C, Cuervo G, Salavert M, et al. An evidence-based bundle improves the quality of care and outcomes of patients with candidaemia. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkz491.

Vergidis P, Clancy CJ, Shields RK, et al. Intra-abdominal candidiasis: the importance of early source control and antifungal treatment. PLoS One. 2016;11(4): e0153247. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153247.

Acknowledgement

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Matteo Bassetti, Maddalena Peghin, Daniele Roberto Giacobbe, Filippo Ansaldi, Cecilia Trucchi, and Antonio Vena made substantial contributions to study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; first drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the other authors made substantial contributions to acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Outside the submitted work, Matteo Bassetti reports grants and personal fees from Pfizer, grants and personal fees from MSD, grants and personal fees from Cidara, personal fees from Astellas, personal fees from Gilead. Daniele Roberto Giacobbe reports personal fees from Stepstone Pharma GmbH and an unconditional grant from MSD Italia. George Dimopoulos reports personal fees from Pfizer, Infectopharm, EU/FP7/Magic Bullet, and a grant for his institution from MSD. Jose Luis Garcia-Garmendia reports a formative grant from MSD, a formative grant from Fresenius, and payment for lecture from AstraZeneca. Bart Jan Kullembert reports grants for his institution from Amplyx, Astellas, and Cidara. Katrien Lagrou has received research grants from Gilead, MSD and Pfizer, consultancy fees from Gilead, Pfizer, Abbott, MSD and SMB Laboratoires Brussels, travel support from Pfizer, Gilead and MSD, and speaker fees from Gilead, Roche, Abbott. Jean-Francois Timsit has received grants for his institution from Pfizer and MSD, personal fees from BioMérieux, and participated in advisory board for MSD, Bayer, 3M, and Gilead. Philippe Montravers reports personal fees from Pfizer and MSD. Oliver A. Cornely reports grants or contracts from Amplyx, Basilea, BMBF, Cidara, DZIF, EU-DG RTD (101037867), F2G, Gilead, Matinas, MedPace, MSD, Mundipharma, Octapharma, Pfizer, Scynexis; Consulting fees from Amplyx, Biocon, Biosys, Cidara, Da Volterra, Gilead, Matinas, MedPace, Menarini, Molecular Partners, MSG-ERC, Noxxon, Octapharma, PSI, Scynexis, Seres; Honoraria for lectures from Abbott, Al-Jazeera Pharmaceuticals, Astellas, Grupo Biotoscana/United Medical/Knight, Hikma, MedScape, MedUpdate, Merck/MSD, Mylan, Pfizer; Payment for expert testimony from Cidara; Participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board from Actelion, Allecra, Cidara, Entasis, IQVIA, Jannsen, MedPace, Paratek, PSI, Shionogi; A patent at the German Patent and Trade Mark Office (DE 10 2021 113 007.7); Other interests from DGHO, DGI, ECMM, ISHAM, MSG-ERC, Wiley. Ignacio Martin Loeches has received speaker fees from Gilead and MSD. MLNGM is co-founder, former President and current Treasurer of WSACS (The Abdominal Compartment Society, www.wsacs.org). He is also co-founder of the international fluid academy (IFA, www.fluidacademy.org). The IFA is integrated within the not-for-profit charitable organization iMERiT, International Medical Education and Research Initiative, under Belgian law. He is also member of the medical advisory Board of Getinge (Pulsion Medical Systems) and Serenno Medical, and consults for Baxter, Maltron, ConvaTec, Acelity, Spiegelberg and Holtech Medical. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Specific informed consent for this study was not necessary because of the retrospective nature of the analyses. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the coordinating centre (Regional Ethics Committee of Friuli-Venezia-Giulia Region, parere CEUR-2017-Os-033-ASUIUD).

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bassetti, M., Vena, A., Giacobbe, D.R. et al. Risk Factors for Intra-Abdominal Candidiasis in Intensive Care Units: Results from EUCANDICU Study. Infect Dis Ther 11, 827–840 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00585-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-021-00585-6