Abstract

Introduction

German data regarding the burden of complications from chronic hepatitis C (CHC) virus infection are limited. To address this issue, this study evaluates the clinical and economic burden of hepatic and extrahepatic complications (EHCs) associated with CHC in Germany.

Methods

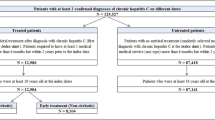

This retrospective, cross-sectional study used claims data from the Betriebskrankenkasse German sickness fund (2007–2014) to assess the risks and medical costs of hepatic complications and EHCs, including conditions that are prevalent and behavioral factors associated with CHC. Prevalence, incidence, and risks were calculated for 1:1 matched patients with and without CHC (n = 3994). All-cause cost, medical costs related to hepatic and EHCs, as well as CHC-related and non-CHC-related pharmacy costs (adjusted to the 2016 Euro rate), were calculated and compared between 1:5 matched patients with (n = 8425) and without CHC (n = 42,125).

Results

Patients with CHC had a 3-fold higher risk for any EHC (OR = 3.0; P < 0.05) and higher EHC-related medical costs (adjusted difference, €1606; P < 0.01) compared with patients without CHC. Total costs (€10,108 vs. €5430), hepatic complication-related medical costs (€1425 vs. €556), EHC-related costs (€3547 vs. €1921), CHC-related pharmacy costs (€577 vs. €116), and non-CHC-related pharmacy costs (€3719 vs. €1479) were all significantly greater for patients with CHC compared with patients without CHC. EHC-related medical costs were a major contributor to the higher all-cause medical (84.4%) and total (44.3%) cost differences between patients with CHC and the matched sample of patients without CHC.

Conclusion

CHC is associated with substantial clinical and economic burden in Germany, largely due to hepatic complications and EHCs.

Funding

Abbvie Inc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is a systemic disease presenting with hepatic and extrahepatic complications (EHCs) [1]. HCV represents a major global health burden with over 80 million people infected worldwide [2], including an estimated 14 million people chronically infected in the WHO European region [3]. The incidence risk of HCV in the European Union (EU) is approximately 8.7 per 100,000 people [4], with a reported 2.6 million individuals infected with viremic HCV in Western Europe [2]. While there are limited data estimating the prevalence of HCV infection in Germany specifically, one 2013 study reported a prevalence estimate of antibodies against HCV in the German population to be 0.3%, similar to the prevalence estimated 10 years prior (0.4%) [5].

The estimated diagnosis rate of HCV is 57% [6], which suggests a relatively large proportion of patients who are living with HCV yet who remain undiagnosed with this disease. Acute HCV infection is typically asymptomatic and often remains undiagnosed, with up to 85% of acutely infected individuals developing chronic hepatitis C (CHC) virus infection [7]. Complications resulting from HCV infection include cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver failure [8], all of which are associated with substantial healthcare costs [9].

In the WHO European region, nearly 112,500 people die each year due to HCV-related liver diseases [3]. In addition to the detrimental effects on the liver, HCV is associated with a number of EHCs, which affect other organ systems, causing progressive illness and possible death [10]. These EHCs include mixed cryoglobulinemia, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, arthralgia, immune thrombocytopenia, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), renal impairment, fatigue, cognitive impairment, depression, cancer, and cardiovascular disorders, among others [11].

A recent global meta-analysis showed the most common EHCs among patients diagnosed with CHC were mixed cryoglobulinemia (30.1%), depression (24.5%), T2DM (15.0%), Sjögren’s syndrome (11.9%), and chronic renal disease (10.1%) [1]. The study also found that the most commonly-studied EHCs were mixed cryoglobulinemia, porphyria cutanea tarda, T2DM, and depression [1]. Other diseases also impact the overall burden associated with CHC. These include Parkinson’s disease, behavioral and mental disorders due to psychoactive substance use, cardiovascular disorders, and non-hepatic malignancies, among others. A recent systematic review has shown that HCV-infected patients have approximately 35% higher risk of Parkinson’s disease as compared with patients without HCV [12]. Substance abuse also contributes to viral exposure due to use of contaminated needles [13]. A direct link does not exist between cardiovascular disorders and HCV infection; however, HCV infection has been reported to increase cardiovascular risk [14]. Furthermore, CHC patients are at an increased risk of cancer, not only because of the infection itself but also due to exposure to other substances such as tobacco and alcohol [15].

HCV-related clinical events pose a significant economic burden in terms of both direct medical costs (such as pharmacy- and treatment-related) and indirect costs (work productivity loss due to absenteeism and/or presenteeism) [1]. The economic burden of HCV has been documented in Europe [16, 17], including data from Germany [18]. However, data that specifically estimate the economic impact attributable to CHC-related EHCs for Germany alone are unavailable. In addition, the clinical and economic burden of CHC-related EHCs is not yet fully understood, given that most studies report on a limited number of EHCs [19]. There is particularly a lack of available data pertaining to the prevalence and burden of CHC-related EHCs in Germany. The aim of this study was to utilize a comprehensive national database from the German Betriebskrankenkasse (BKK) sickness fund, to assess the clinical and economic burden of a broad range of CHC-related EHCs.

Methods

Data Sources

Reimbursement data from the BKK sickness fund cover 5.2 million persons (as of 2012), which includes patients’ medical (i.e., inpatient and outpatient claims), prescription drugs, and insurance eligibility information. Data from 2007 through 2014 were utilized for HCV-diagnosed patients and matched non-HCV controls. The BKK were informed about the project and all the required approvals were obtained. Patient data were fully anonymized according to accepted standard procedures.

Study Definitions

Prevalent patients with CHC were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition German Modification (ICD-10-GM) code B18.2 in outpatient and/or inpatient care data in any of the quarters in the identification period (Q1/2008 through Q1/2014). Only patients with a diagnosis of CHC preceded and followed by at least 4 quarters of full insurance were considered for inclusion. For inpatient data, primary CHC discharge diagnoses as well as secondary diagnoses were checked. For outpatient data, only assured diagnoses (marked by “G” or “Z”) were considered and required evidence of a second diagnosis code within 3 quarters pre- or post-identification.Footnote 1

Extrahepatic Complications (EHCs)

EHCs included extrahepatic manifestations (EHMs), which have a documented clinical pathway with CHC, as well as other conditions and behavioral factors which, although no clinical pathway has been established, are prevalent among the patient population. EHMs investigated in this study included the broader disease categories of T2DM, cardiovascular disease (CVD), fatigue, renal impairment, and malignancies. Other prevalent diseases observed in the patient population were mental and behavioral disorders (due to opioids, multiple drug use, and other psychoactive substances); Parkinson’s disease; and some cardiovascular, renal, and other diseases not documented as EHMs. EHMs, behavioral factors, and other prevalent conditions in the population are jointly called EHCs for this study. The complete list of diseases within each grouping and its disease category, as well as their associated ICD-10-GM codes, is presented in Table 1.

Clinical Burden Analyses: Cumulative Prevalence and Incidence of EHCs

The cumulative prevalence and incidence of the EHCs were compared between patients with prevalent CHC matched to controls with no evidence of CHC to assess the clinical burden of these diseases. Patients were required to be insured at least 4 quarters of look-back and at least 20 quarters of follow-up, as the prevalence and incidence were calculated for 5 years of follow-up. For patients with CHC, the index quarter was defined as the quarter of the first CHC diagnosis, using data from Q1/2008 to Q1/2014. Controls were identified as having no evidence of CHC in the entire study period. Matching was carried out 1:1 on index quarter, age (in 5-year-categories), sex, and the previous year’s healthcare costs (in categories; 0 Euro, and 23 quantiles of cost > 0 Euro). The annual prevalence was calculated separately for both cohorts, and the number of patients suffering from each/any of the EHCs was measured in each of the 5 years of follow-up (F/U) to assess annual prevalence. Incidence was defined as the proportion of newly diagnosed patients in the period of interest among patients at risk at the start of the period of interest. Four-year cumulative incidence rates of the EHCs were calculated separately for both cohorts, based on F/U2 through F/U5. The prevalence, incidence, and risks of the EHCs were compared between the matched study cohorts using unadjusted logistic models, odds ratios (OR), and P values.

Economic Burden Analyses

Medical Cost Definitions

Annualized total costs were assessed from the index quarter until the end of patient follow-up, which corresponded to the end of continuous insurance time, based on whether the patient died or switched to another health insurance, or the end of data availability on December 31, 2014. Therefore, while follow-up time may have differed in length across patients, annualizing the costs served to make patients’ follow-up time comparable. To quantify the economic burden of CHC, annual costs were compared between matched patients with and without CHC.

The sum of all-cause medical and pharmacy costs is referred to as total cost. All-cause medical costs were further broken down into medical costs related to hepatic and extrahepatic complications. Pharmacy costs were split into CHC-related and non-CHC-related costs. CHC-related costs were defined as those associated with esophageal varices, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, cirrhosis of the liver, hepatic encephalopathy (liver failure), portal hypertension, ascites, splenomegaly, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatocellular carcinoma, porphyria cutanea tarda, and liver transplantation. Costs attributable to CHC-related EHCs were identified using relevant German Uniform Assessment Standard (EBM) codes, Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) codes, and Operation and Procedure (OPS) codes. EBM codes are relevant in the setting of medical practitioners, while DRG and OPS codes are relevant in the setting of hospitals (in- and outpatient care). In addition, claims from sickness benefits (medical leave benefits received by employees after 6 weeks of inability to work), which were based on relevant ICD-10-GM codes, were included in the EHC costs. Likewise, medical costs related to hepatic complications were identified by searching for relevant EBM, DRG, OPS, and ICD-10-GM codes that are associated with hepatic complications. Claims associated with both CHC–associated EHCs and hepatic complications were attributed to both categories. Total all-cause medical costs contain costs for practitioner, hospital in- and outpatient care, as well as sickness benefits. In addition to EHC-related or hepatic complications-related medical costs, all other costs that occur due to any disease were included in total all-cause medical costs. CHC-related pharmacy costs were identified for 12 CHC drugs, while all other pharmacy costs were summarized as non-CHC-related pharmacy costs (Table 2). Costs were calculated as average, annualized charged amounts and adjusted to reflect average 2016 Euro exchange rates.

Mean costs differences estimated from unadjusted and adjusted ordinary least squares regression models were used to compare the medical costs between study cohorts. Models were adjusted for age (in years), gender, and the previous year’s total healthcare costs.

Economic Burden of CHC

A retrospective cohort study was performed to estimate the medical costs between patients with and without CHC. Patients with a CHC diagnosis were matched to controls with no evidence of CHC ever in the study period. Controls were selected from the same index quarter and met the same insurance criteria, requiring four quarters of insurance coverage pre- and post-index. One random quarter between Q1/2008 and Q1/2014 in which CHC patients showed a relevant diagnosis was used as their identification/index quarter, and this anchored their look-back and follow-up. The CHC cohort was matched 1:5 to controls on age (in categories of 5 years each), gender, and the previous year’s total healthcare costs (in 38 categories, i.e., 0 and 37 quantiles for cost > 0 Euro).

All analyses were conducted using SAS v.9.4. Alpha of 0.05 was used as the cut-off for determining statistical significance.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously available data, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. However, appropriate approvals from the BKK were obtained in order to use their data for this study.

Similar data were used in a study assessing the role of treatment in reducing the economic burden of hepatic and EHCs associated with CHC in Germany. That study found that treatment may reduce the burden of CHC and result in substantial cost savings, even when initiated at earlier stages of the disease, subject to similar limitations as the present study [25].

Results

Clinical Burden: Cumulative Prevalence and Incidence and Risk of CHC-related EHCs

In general, the prevalence and incidence of the EHCs was greater in the CHC cohort (n = 3994) versus the cohort without CHC (n = 3994) (Table 3). The exceptions were cardiovascular and Parkinson’s disease, though the prevalence gap was significantly different only for CVD. The prevalence in the CHC cohort for any of the EHCs was significantly higher than the controls with no-CHC for each year of follow-up (F/U), with a 3-fold greater risk (OR = 3.0; P < 0.05; Table 3) in the fifth year of F/U (data for F/U2 through F/U4 not shown). Patients with CHC had significantly greater annual risks in the majority of follow-up years for mental and behavioral disorders (due to opioids, multiple drug use, and other psychoactive substances; F/U5 OR = 22.0), fatigue (F/U5 OR = 1.9), renal impairment (F/U5 OR = 1.4), and malignancies (F/U5 OR = 1.9), all P < 0.05. The 4-year cumulative incidence rate for any of the EHCs was also significantly higher in the CHC cohort than in the no-CHC cohort (OR = 1.1; P < 0.05). The EHCs with significantly greater 4-year cumulative incidence risk (F/U2 through F/U5) in CHC patients were mental and behavioral disorders (due to opioids, multiple drug use, and other psychoactive substances; OR = 4.0), malignancies (OR = 2.9), fatigue (OR = 1.6), and renal impairment (OR = 1.4), all P < 0.05.

Economic Burden of HCV

A total of 8425 patients with CHC were identified and matched to 42,125 patients without HCV to compare the economic burden associated with HCV. Patients with HCV were 55.7% male with a mean age of 52.0 years [standard deviation (SD) = 28.7], while those without HCV were also 55.7% male with a mean age of 52.4 years (SD = 13.8) (Table 4). The total costs (€10,108 vs. €5430, adjusted difference €3628), hepatic complications-related medical costs (€1425 vs. €556, adjusted difference €865), EHC-related costs (€3547 vs. €1921, adjusted difference €1606), CHC-related pharmacy costs (€577 vs. €116, adjusted difference €454), and non-CHC-related pharmacy costs (€3719 vs. €1479, adjusted difference €1272) were all significantly higher for the CHC cohort than the no-CHC cohort (P < 0.01 for all; Table 5). EHC-related medical costs were a major contributor to the higher all-cause medical (84.4%) and total (44.3%) adjusted cost differences observed.

Discussion

In the current German BKK sickness fund data analysis, for the first time, the all-cause medical, pharmacy, hepatic complication- and EHC-related medical costs were compared between matched patients with and without CHC. The results showed that CHC was significantly associated with clinical and economic burden attributable to hepatic and EHCs. Results concerning the economic burden associated with CHC were consistent with recent evidence from the US [20]. However, in contrast to previous results [19, 21], the prevalence of cardiovascular disease was significantly higher in the cohort without CHC than the CHC cohort. This also contrasts the difference in economic burden attributed to cardiovascular EHCs observed in the present study, where the CHC cohort incurs a greater cost (Table 5). As the clinical burden analysis was limited to people with at least 5 years of data, it is possible that the sample was skewed to a healthier population resulting from the exclusion of patients with CVD passing away or lost to follow-up within this 5-year period.

CHC patients in this study had 3-fold higher risks in the last follow-up year of this study for any EHC, and higher total cost, all-cause medical, and EHC-related medical costs (adjusted annual cost differences €3628, €1902, and €1606, respectively) compared to patients without CHC. Similarly, a meta-analysis by Younossi et al. [1] found HCV to be a risk factor for developing new EHMs including kidney disease, lymphoma, depression, and T2DM. Using a US claims database, Reau et al. [20] demonstrated that EHMs contributed to the overall clinical and economic burden of HCV and its treatment. Of the EHMs assessed, kidney disease and CVD were the costliest EHMs across HCV versus no-HCV. The results observed in our study are comparable to Reau et al.’s US study, with the share of the all-cause medical costs attributable to EHCs being 84.4% for HCV versus no-HCV cohorts. Regarding clinical burden, the HCV cohort in the current study showed greater risk of contracting any EHC compared to the US study (OR 3.0 vs. 2.2).

A European study evaluating all-cause medical costs from 5 countries, including Germany, showed that costs were greater for patients with HCV compared with patients without HCV [17]. However, the all–cause medical costs were lower in the European study compared with the current study (€1147 vs. €5812). A major driver of this difference may be that the European study used medical costs calculated using an average price reported in literature and adjusting for 2010 inflation values. The current study used a single data source to calculate German costs through 2014 and, hence, these price and time-period differences could have influenced the costs in addition to inflation.

Cacoub et al. [22] recently used an economic model to estimate the burden of EHMs in European HCV patients. These authors analyzed EHMs not included in the present study, such as lichen planus, Sjögren’s syndrome, and rheumatoid-like arthritis. The EHC-related medical costs in the current study were almost 3-fold higher (€3547 vs. €1247) than in the European study [22]. The higher cost observed in the current study could be due to the data collection methods used; for example, Cacoub et al. obtained data from various sources including literature, national databases, and expert opinion, whereas the current study used data from a single database.

The strength of our study is the inclusion of a broad range of EHCs, including some that have not been studied extensively (e.g., mental disorders, gastric disorders), which enabled us to understand the clinical and economic burden of CHC in Germany. EHC is a broader term than EHM because the former only encompasses conditions that have a documented clinical pathway to CHC, while the latter also includes conditions that are prevalent among the patient population but are not yet shown to be related to CHC.

Limitations

The limitations of the current study must be kept in mind while interpreting the results. The BKK data only represent ~ 8% of all people within the statutory health insurance system. Residual confounding may persist despite sample matching and covariate adjustment in the analyses. Patients could be misclassified due to misinterpretation of EBM, DRG, OPS, and ICD-10-GM codes. CHC is a chronic disease; hence, a possibility of lag between infection and diagnosis cannot be excluded. It is possible that some of the patients in the no-CHC cohort were infected but undiagnosed, potentially underestimating the risk of EHCs; however, with a HCV prevalence of 0.3% in Germany [5], the bias introduced by undiagnosed HCV patients in the no-HCV cohort must be very small. Some EHC categories such as cardiovascular disorders and renal impairment are comprised of both EHMs documented in the literature and other conditions that are prevalent in this population. The medical costs were measured as charged amounts, and not paid amounts, which may result in overestimation of the actual cost. However, this is likely to affect all the cohorts equally. In addition, a single medical claim could be associated with multiple procedure codes, resulting in the same medical cost being counted under multiple EHM categories. However, these costs were only included once while performing summation. Also, not all EHCs were included in the analysis and those included were grouped together which could affect the respective cost analyses. Moreover, data are used from a large span of time (2007–2014), which introduces a high level of heterogeneity regarding patient characteristics, making interpretation of the data and results more difficult.

Conclusion

The current study findings reveal that CHC is associated with a high risk of EHCs and imposes a substantial economic burden. Not treating CHC or delaying treatment to advanced stages of liver disease may result in additional expenditures, mainly due to EHC-related complications. The results observed in this study may help guide clinical decision making for the improvement of care for patients with CHC, which in turn could lead to significant cost savings for payers and society alike.

Notes

G (abbreviation for "gesicherte Diagnose") = assured diagnosis; Z ("Zustand nach") = condition after.

References

Younossi Z, Park H, Henry L, et al. Extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C: a meta-analysis of prevalence, quality of life, and economic burden. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1599–608.

Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, et al. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014;61:S45–57.

Hepatitis C in the WHO European Region. World Health Organization; 2017. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/283357/fact-sheet-en-hep-c-edited.pdf. Accessed: 13 Sep 2017.

Data and statistics. World Health Organization. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/hepatitis/data-and-statistics. Accessed: 13 Sep 2017.

Poethko-Muller C, Zimmermann R, Hamouda O. et al [Epidemiology of hepatitis A, B, and C among adults in Germany: results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:707–15.

Razavi H, Waked I, Sarrazin C, Myers RP, Idilman R, Calinas F, et al. The present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with today’s treatment paradigm. J Viral Hepatitis. 2014;21(Suppl 1):34–59.

Guidelines for the screening, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis C infection. World Health Organization; 2016 April. (ISBN 978 92 4 154961 5).

Younossi ZM, Tanaka A, Eguchi Y, et al. The impact of hepatitis C virus outside the liver: evidence from Asia. Liver Int. 2017;37:159–72.

Nevens F, Colle I, Michielsen P, et al. Resource use and cost of hepatitis C-related care. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1191–8.

Carrozzo M, Scally K. Oral manifestations of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7534–43.

Cacoub P, Comarmond C, Domont F, et al. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2016;3:3–14.

Wijarnpreecha K, Chesdachai S, Jaruvongvanich V, Ungprasert P. Hepatitis C virus infection and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:9–13.

Khalsa JH, Treisman G, McCance-Katz E, Tedaldi E. Medical consequences of drug abuse and co-occurring infections: research at the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Subst Abus. 2008;29:5–16.

Petta S. Hepatitis C virus and cardiovascular: a review. J Adv Res. 2017;8:161–8.

Balakrishnan M, Glover MT, Kanwal F. Hepatitis C and risk of nonhepatic malignancies. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;21:543–54.

Dibonaventura MD, Yuan Y, Lescrauwaet B, et al. Multicountry burden of chronic hepatitis C viral infection among those aware of their diagnosis: a patient survey. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:SP227-35.

Vietri J, Prajapati G, El Khoury AC. The burden of hepatitis C in Europe from the patients’ perspective: a survey in 5 countries. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:16.

Stahmeyer JT, Rossol S, Bert F, et al. Cost of treating hepatitis C in Germany: a retrospective multicenter analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:1278–85.

Solinis RN, Ugarte PA, Rojo A, et al. Value of treating all stages of chronic hepatitis C: a comprehensive review of clinical and economic evidence. Infect Dis Ther. 2016;5:491–508.

Reau N, Vekeman F, Wu E, et al. Prevalence and economic burden of extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus are underestimated but can be improved with therapy. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1:439–52.

Tengan FM, Levy-Neto M, Miziara ID, Dantas BP, Maragno L. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C infection: a consecutive study in Brazilian patients. Braz J Infect Dis. 2017;21:203–4.

Cacoub P, Buggisch P, Beckerman R, et al. Direct medical costs associated with the extrahepatic manifestations of hepatitis C infection. J Hepatol. 2017;66:S499.

Mohammed RH, ElMakhzangy HI, Gamal A, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among Egyptians. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29:1373–80.

Cheng Z, Zhou B, Shi X, et al. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection: 297 cases from a tertiary medical center in Beijing, China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127:1206–10.

Kraus, M.R., Kleine, H., Thönnes, S. et al. Improvement of hepatic and extrahepatic complications from chronic hepatitis C after antiviral treatment: a retrospective analysis of German sickness fund data. Infect Dis Ther (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-018-0205-2.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were provided by AbbVie. AbbVie participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the publication. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Ramu Periyasamy, Ph.D. and Leo J Philip Tharappel of Indegene provided medical writing and editing services on behalf of Kantar Health in the development of this publication. Shawna Calhoun, MPH and Michael J. Doane, Ph.D. of Kantar Health also provided assistance with writing. AbbVie Inc. provided funding for editorial assistance to Kantar Health.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez, Marc Pignot, and Stefanie Thönnes were involved in the conception and design of the study, as well as the analysis and interpretation of the data. Michael R. Kraus and Henning Kleine were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript for intellectual content and the final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosures

Michael R. Kraus is an employee of Hospital Altötting-Burghausen and is a consultant for AbbVie Inc. Marc Pignot is an employee of Kantar Health. Stefanie Thönnes is an employee of Team Gesundheit GmbH and conducted work on behalf of Kantar Health. Kantar Health received funds from AbbVie for conducting the study, analysis, and reporting of findings. Yuri Sanchez Gonzalez is an employee of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock or stock options. Henning Kleine is an employee of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stock or stock options.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously available data, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. However, appropriate approvals from the BKK were obtained in order to use their data for this study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to protections around the public sharing of private health information.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6391385.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kraus, M.R., Kleine, H., Thönnes, S. et al. Clinical and Economic Burden of Hepatic and Extrahepatic Complications from Chronic Hepatitis C: A Retrospective Analysis of German Sickness Fund Data. Infect Dis Ther 7, 327–338 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-018-0204-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-018-0204-3