Abstract

Introduction

Approximately 30% of all outpatient antimicrobials are inappropriately prescribed. Currently, antimicrobial prescribing patterns in emergency departments (ED) are not well described. Determining inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing patterns and opportunities for interventions by antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASP) are needed.

Methods

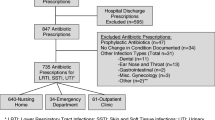

A retrospective chart review was performed among a random sample of non-admitted, adult patients who received an antimicrobial prescription in the ED from January 1 to December 31, 2015. Appropriateness was measured using the Medication Appropriateness Index, and was based on provider adherence to local guidelines. Additional information collected included patient characteristics, initial diagnoses, and other chronic medication use.

Results

Of 1579 ED antibiotic prescriptions in 2015, we reviewed a total of 159 (10.1%) prescription records. The most frequently prescribed antimicrobial classes included penicillins (22.6%), macrolides (20.8%), cephalosporins (17.6%), and fluoroquinolones (17.0%). The most common indications for antibiotics were bronchitis or upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) (35.1%), followed by skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) (25.0%), both of which were the most common reason for unnecessary prescribing (28.9% of bronchitis/URTIs, 25.6% of SSTIs). Of the antimicrobial prescriptions reviewed, 39% met criteria for inappropriateness. Among 78 prescriptions with a consensus on appropriate indications, 13.8% had inappropriate dosing, duration, or expense.

Conclusion

Consistent with national outpatient prescribing, inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the ED occurred in 39% of cases with the highest rates observed among patients with bronchitis, URTI, and SSTI. Antimicrobial stewardship programs may benefit by focusing on initiatives for these conditions among ED patients. Moreover, creation of local guideline pocketbooks for these and other conditions may serve to improve prescribing practices and meet the Core Elements of Outpatient Stewardship recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Overuse of antimicrobials is a major driver of antimicrobial resistance which threatens the health of people all over the world [1, 2]. On May 20, 2017, antimicrobial resistance was recognized and discussed at the Group of Twenty (G20) Summit by leaders from around the world. Together with the World Health Organization, World Organization for Animal Health, and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the G20 is preparing a global report with three recommendations: promote conservation of antimicrobials, optimize utilization, as underuse, like overuse, can contribute to antimicrobial resistance, and invest in innovations that can help bring new antimicrobials, vaccines, and diagnostics to market [3]. Consistent with the first two recommendations, antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have improved antimicrobial use in hospitals through those interventions [4]. However, nearly two-thirds of antibiotic expenditures occur in the outpatient setting, indicating an important area of need for antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) [5, 6].

To improve antimicrobial use in outpatient settings, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently released the Core Elements of Outpatient Stewardship [6]. These recommendations include four elements: commitment to improving antibiotic prescribing and patient safety, implementation of at least one policy or practice, tracking and reporting antimicrobial prescribing practices, and providing education and expertise to clinicians and patients on antimicrobial prescribing. These core elements are timely as calls to action for AMS targeting emergency departments (ED) as part of the outpatient setting have gained interest [7, 8]. Prior to addressing the Core Elements of Outpatient Stewardship individually, the CDC recommends identifying high-priority indications (e.g., respiratory infections) for targeted intervention. Overall, 1/3 of antibiotics in the outpatient setting, including EDs and outpatient clinics, are inappropriately prescribed with respiratory tract infections attributing to the majority of inappropriate prescriptions, yielding a significant area of opportunity for AMS [9, 10]. However, overall rates of inappropriate prescribing specific to ED settings are lacking in the US. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine rates of inappropriate antimicrobial use and define specific areas of opportunity for AMS interventions in the ED.

Methods

Setting and Patients

The Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center (PVAMC) is a 119-bed teaching hospital located in Providence, Rhode Island, USA. Patients included in this period prevalence study were a randomly selected 10% sample of non-admitted patients 18 years of age or older, who were prescribed an antimicrobial medication in the PVAMC ED and filled at the PVAMC pharmacy from January 1 to December 31, 2015. In 2012, the PVAMC implemented an ASP, in which the infectious diseases pharmacy fellows provide prospective audit and feedback for admitted patients [11]. However, ED patients were not routinely monitored by the ASP during this study period. Moreover, the ASP distributed an antimicrobial guidebook, but no specific interventions or education had been provided to the emergency department on the use of the local guidelines before or during this period.

Data Collection and Assessment

Data collection was performed by a clinical pharmacist and an internal medicine physician. Both clinicians had complete access to the electronic medical records of the included patients. Specific data collected included: patient demographics, encounter infectious diagnosis, temperature, white blood cell count, antimicrobial prescribed (dose, route, duration), concomitant chronic medications, and appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing based on chart assessment. Both the clinical pharmacist and physician retrospectively assessed the appropriateness of antibiotic therapy prescribed based on the documented diagnosis received in the ED for each patient.

Appropriateness was measured using the Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) [12]. The MAI is a validated tool that assesses the appropriateness of 10 different areas of medication prescribing: indication, effectiveness, dosage (based on indication and renal function), directions, practicality, drug–drug interactions, drug–disease interactions, duplication, duration, and expense [13, 14]. For every prescribed medication, the reviewers answered each of the 10 questions in the MAI with either A (appropriate), B (not clearly appropriate), or C (inappropriate). Assessments on the appropriateness of therapy were made according to local antibiotic use guidelines summarized in a guidebook tool (http://web.uri.edu/antimicrobial-stewardship/) which was derived from national practice guidelines endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and/or CDC. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted within the VA [15].

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center. This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for patient characteristics, clinical presentation including infectious diagnosis, characteristics of prescribed antibiotic (dose, duration, etc.), and MAI results. MAI responses were categorized as appropriate (appropriate) and inappropriate (inappropriate or not clearly appropriate) [16]. In calculating inappropriate prescribing rates, for a prescription to be defined as inappropriate, it had to be categorized as such by consensus between the clinical pharmacist and internal medicine physician. Kappa statistics for interrater reliability were calculated for the overall MAI, each MAI category, and by infection type [17, 18].

Results

Of 1579 ED-associated antibiotic prescriptions in 2015, we reviewed a total of 159 (10.1%) prescription records for 148 patients, excluding 2 patients who were subsequently admitted during the same visit. Patient characteristics and prescribing indications can be found in Table 1. The median age was 60 and most patients were male (91.2%). Concomitant chronic medication use was common (median 8, interquartile range 3–13). The most common indications for antibiotics were bronchitis or upper respiratory tract infection (URTI, 35.1%), followed by skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI, 25.0%). As reflected in Table 2, frequently prescribed antibiotics included penicillins (22.6%), macrolides (20.8%), cephalosporins (17.6%), and fluoroquinolones (17.0%).

A summary of inappropriate prescribing based on MAI criteria is shown in Table 3. Thirty-nine percent of antimicrobial prescriptions were classified as inappropriate. Inappropriate prescribing varied by indication: bronchitis/URTI (15/52, 28.9%), SSTI (10/39, 25.6%), intra-abdominal infections (15.0%; 3/20), community-acquired pneumonia (CAP; 3/9, 33.3%), urinary tract infection (UTI; 2/8, 25.0%), and other conditions (4/14, 28.6%). Of the 79 (49.7.8%) prescriptions with a consensus on appropriate indication, inappropriate prescribing was noted among 13.8% of prescriptions with regards to dose, duration, or expense, while the other MAI categories reflected no inappropriate prescribing based on reviewer consensus. CAP and UTI dosing were found to be inappropriate in 11.1% and 12.5% of cases, respectively. Inappropriate durations were found in 6.0% of bronchitis/URTI, 7.7% of SSTI, and 5.0% of intra-abdominal infections. Excessive expense was noted in 11.1% of CAP, and only 2% of bronchitis/URTI.

Overall, interrater reliability of the MAI was high (k = 0.90). The kappa statistics for indication, dose, and duration were 0.46, 0.47, and 0.26, respectively. Though other MAI categories had high positive agreement for appropriateness (median 85, IQR 79–98), kappa statistics could not be calculated for these MAI categories due to the lack of negative agreement (determined as inappropriate by both reviewers). Kappa scores by indication were also high, with a median of 0.82 (IQR 0.58–0.91).

Discussion

The present study reflects the first ED inappropriate prescribing assessment reported in the US, with 39% of prescribing found to be inappropriate as defined by the MAI and local guidelines. The two most common indications, SSTI and bronchitis/URTI, also had the highest rates of inappropriate prescribing (25.6% and 28.9%) aside from CAP where ~ 1/3 of antibiotics were not indicated based on diagnostic criteria from a chart review. These results are consistent CDC data which found ~ 1/3 of antibiotic prescriptions in the outpatient setting, including outpatient clinics and EDs, as being inappropriate [9].

Similar to studies from outpatient clinic settings, we found an opportunity for AMS among patients with a diagnosis of bronchitis or URTI patients with 28.9% of prescribing being inappropriate based on indication [9, 10]. In our older population of Veterans, the prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is more than double that of the general US population [19, 20]. Therefore, many of these patients may have had a history of COPD, and thus components of COPD exacerbation requiring antibiotics. Our local guidance, concordant with national guidelines for bronchitis and URTIs, infrequently recommends antibiotics since > 90% of patients presenting with a new onset cough for outpatient treatment have a virus [21].

To assist in diagnostic uncertainty for respiratory indications, rapid diagnostic testing, both procalcitonin and respiratory viral panels, have been shown to help in decreasing inappropriate antibiotic use among patients presenting with respiratory illnesses with possible infectious etiologies [22, 23]. However, these technologies may be suboptimal in decreasing inappropriate antibiotic use unless there is education and AMS guidance along with audit and feedback [24]. Future efforts should focus on how to optimize implementation of diagnostic testing within the ED to increase appropriate use of antibiotics in patients with respiratory tract infections. Clinician education has also been shown to be an effective intervention modality for decreasing antimicrobial use in adults with acute respiratory infections treated in EDs [25].

Another important area of opportunity identified for improved prescribing was with SSTIs. We found 25.6% of prescribing for SSTIs was inappropriate based on indication. Current national guidelines recommend against the use of antibiotics for uncomplicated skin abscesses which have undergone incision and drainage, yet this practice remains common [26, 27]. A study of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) from 2007 to 2010 found that 87% of visits for abscesses which had incision and drainage were still prescribed antibiotics [27]. Adaptation of and education on ED-specific national guidelines may encourage ED providers to execute more judicious use [28].

While comprehensive assessments of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions in the ED have not been previously reported in the US, a recent study in France found that 59.9% (455/760) of prescriptions in the ED were inappropriate [29]. This was higher than our observed 39% which may be due to differences in patient populations, as well as national and local treatment guidelines. Similar to our study, however, they found high rates of inappropriate prescribing for respiratory tract infections (46.5%), SSTIs (71.2%), and UTIs (38.4%). We also observed high inappropriate prescribing for UTIs (37.5%). Education on optimal empiric treatments given high resistance to therapies like fluoroquinolones has been shown to improve empiric prescribing [30, 31].

To date, there has been a single study reporting on a comprehensive AMS initiative in the ED [32]. This was a single center study at a 497-bed tertiary university hospital in France with about 35,000 ED visits per year. An intervention bundle was employed consisting of a 0.2 infectious diseases (ID) physician full-time equivalent for advising during business hours, educating staff every 6 months on stewardship principles, creating a treatment guideline pocketbook, appointing an ED antimicrobial champion to attend daily staff meetings and promote optimal antimicrobial use, and reviewing ED antibiotic prescribing and culture results twice weekly by the ID physician. Antimicrobials were prescribed in 769 visits during the pre-implementation period and 580 visits in the post-implementation period. Prescriptions were not compliant with guidelines in 62.9% of the pre- and 46.7% of the post-implementation visits (p < 0.001). Non-indicated prescriptions decreased by 8.2% (< 0.001), while prescriptions with excessive duration decreased by 2.2% (non-significant). The bundled intervention in this study consisted of various stewardship activities which would be useful to address inappropriate antimicrobial prescribing in an ED. These activities are also supported by a systematic review of AMS in outpatient settings [33].

Measuring inappropriate rates of antimicrobial prescribing is important, yet challenging [34]. A recent study evaluating antimicrobial appropriateness with computerized case vignettes, as reviewed by two infectious diseases physicians, demonstrated a kappa of 0.01 after initial independent review, 0.34 after discussion of case disagreements, and 0.72 after uniform application of institutional guideline criteria. In our initial pilot study, 50 randomly selected patients were evaluated using national guidelines without a summary tool or local guidelines and resulted in a lower overall interrater reliability (k = 0.30), hence the use of local guidelines substantially improved our interrater reliability (k = 0.90). The importance of assessing antibiotic appropriateness using local guidelines to decrease subjectivity and increase reproducibility of assessments has been suggested elsewhere [35]. In fact, this is part of the CDC core elements for outpatient stewardship’s initial steps: establishing standards for antibiotic prescribing [6]. They recommend to consider adapting national guidelines to establish clear expectations for appropriate antibiotic prescribing.

There are several limitations to this study. Our study was a single center in a VA ED. Moreover, given our sample size, outcomes of inappropriate prescribing were not assessed. Future comprehensive assessments of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the ED should be evaluated in community hospital settings to assess differences among non-Veteran populations and should attempt to evaluate outcomes of inappropriate prescribing. Due to data collection limitations, this study did not capture patients who did not fill their prescriptions at the PVAMC pharmacy. Additionally, we only evaluated patients who were prescribed an antibiotic, indicating a potential selection bias. The use of the kappa statistic limited our ability to calculate interrater reliability for some MAI categories due to a lack of negative agreement (determined as inappropriate by both reviewers), especially when there were high rates of appropriateness. We evaluated only empiric prescribing and did not evaluate culture results; therefore, our inappropriate rates of antibiotic use are likely conservative. However, extensive literature on the value of AMS in culture result follow-up reflects both the need and the benefit of AMS in optimizing definitive therapy and the discontinuation of therapy in the absence of organism growth [36,37,38,39,40]. While our local guidelines provided objective assessment criteria for many indications, they were not exhaustive, and, therefore, decisions on certain indications relied more heavily on clinical judgment.

Conclusion

Consistent with national outpatient prescribing, inappropriate prescribing was identified in 39% of antibiotic prescriptions in the ED with the highest rates among patients with bronchitis, URTI, and SSTI. ASPs may benefit by focusing on initiatives for these conditions in the ED setting. Moreover, creation of local guideline pocketbooks may improve prescribing practices, with these activities together meeting the CDC recommended Core Elements of Outpatient Stewardship.

References

Shallcross LJ, Davies DS. Antibiotic overuse: a key driver of antimicrobial resistance. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(629):604–5.

Wise RHT, Otto C, Streulens M, Helmith R, Huovinen P, Sprenger M. Antimicrobial resistance Is a major threat to public health. BMJ. 1998;317:609–10.

G20 Health Ministers’ meeting: fighting antimicrobial resistance. 2017. Paris: OECD.

Schuts EC, Hulscher MEJL, Mouton JW, et al. Current evidence on hospital antimicrobial stewardship objectives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(7):847–56.

Suda KJ, Hicks LA, Roberts RM, Hunkler RJ, Danziger LH. A national evaluation of antibiotic expenditures by healthcare setting in the United States, 2009. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(3):715–8.

Sanchez GV, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(6):1–12.

May L, Cosgrove S, L’Archeveque M, et al. A call to action for antimicrobial stewardship in the emergency department: approaches and strategies. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(1):69–77 e2.

Bishop BM. Antimicrobial stewardship in the emergency department: challenges, opportunities, and a call to action for pharmacists. J Pharm Pract. 2016;29(6):556–63.

Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010–2011. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1864–73.

Parente DM, Timbrook TT, Caffrey AR, LaPlante KL. Inappropriate prescribing in outpatient healthcare: an evaluation of respiratory infection visits among veterans in teaching versus non-teaching primary care clinics. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6:33.

Morrill HJ, Caffrey AR, Gaitanis MM, LaPlante KL. Impact of a prospective audit and feedback antimicrobial stewardship program at a veterans affairs medical center: a six-point assessment. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0150795.

Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(10):1045–51.

Kassam R, Martin LG, Farris KB. Reliability of a modified medication appropriateness index in community pharmacies. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(1):40–6.

Tobia CC, Aspinall SL, Good CB, Fine MJ, Hanlon JT. Appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing in veterans with community-acquired pneumonia, sinusitis, or acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis: a cross-sectional study. Clin Ther. 2008;30(6):1135–44.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Taylor CT, Stewart LM, Byrd DC, Church CO. Reliability of an instrument for evaluating antimicrobial appropriateness in hospitalized patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(3):242–6.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–82.

Spinewine A, Dumont C, Mallet L, Swine C. Medication appropriateness index: reliability and recommendations for future use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):720–2.

DE Murphy CZ, Almoosa KF, Panos RJ. High prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among veterans in the urban midwest. Mil Med. 2011;176:552–60.

Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, Lydick E. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(11):1683.

Harris AM, Hicks LA, Qaseem A, High Value Care Task Force of the American College of P, for the Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Appropriate antibiotic use for acute respiratory tract infection in adults: advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(6):425–34.

Brendish NJ, Malachira AK, Armstrong L, et al. Routine molecular point-of-care testing for respiratory viruses in adults presenting to hospital with acute respiratory illness (ResPOC): a pragmatic, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(5):401–11.

Albrich WC, Dusemund F, Bucher B, et al. Effectiveness and safety of procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy in lower respiratory tract infections in “real life”: an international, multicenter poststudy survey (ProREAL). Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(9):715–22.

Timbrook T, Maxam M, Bosso J. Antibiotic discontinuation rates associated with positive respiratory viral panel and low procalcitonin results in proven or suspected respiratory infections. Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4(3):297–306.

Metlay JP, Camargo CA Jr, MacKenzie T, et al. Cluster-randomized trial to improve antibiotic use for adults with acute respiratory infections treated in emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(3):221–30.

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–52.

Pallin DJ, Camargo CA Jr, Schuur JD. Skin infections and antibiotic stewardship: analysis of emergency department prescribing practices, 2007–2010. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(3):282–9.

Pollack CV Jr, Amin A, Ford WT Jr, et al. Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI): practice guidelines for management and care transitions in the emergency department and hospital. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(4):508–19.

Grenet J, Davido B, Bouchand F, et al. Evaluating antibiotic therapies prescribed to adult patients in the emergency department. Med Mal Infect. 2016;46(4):207–14.

Hudepohl NJ, Cunha CB, Mermel LA. Antibiotic prescribing for urinary tract infections in the emergency department based on local antibiotic resistance patterns: implications for antimicrobial stewardship. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(3):359–60.

Percival KM, Valenti KM, Schmittling SE, Strader BD, Lopez RR, Bergman SJ. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship intervention on urinary tract infection treatment in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1129–33.

Dinh A, Duran C, Davido B, et al. Impact of an antimicrobial stewardship programme to optimize antimicrobial use for outpatients at an emergency department. J Hosp Infect. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2017.07.005.

Drekonja DM, Filice GA, Greer N, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship in outpatient settings: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(2):142–52.

Schwartz DN, Wu US, Lyles RD, et al. Lost in translation? Reliability of assessing inpatient antimicrobial appropriateness with use of computerized case vignettes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(2):163–71.

Spivak ES, Cosgrove SE, Srinivasan A. Measuring appropriate antimicrobial use: attempts at opening the black box. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(12):1639–44.

Davis LC, Covey RB, Weston JS, Hu BB, Laine GA. Pharmacist-driven antimicrobial optimization in the emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73(5 Suppl 1):S49–56.

Baker SN, Acquisto NM, Ashley ED, Fairbanks RJ, Beamish SE, Haas CE. Pharmacist-managed antimicrobial stewardship program for patients discharged from the emergency department. J Pharm Pract. 2012;25(2):190–4.

Randolph TC, Parker A, Meyer L, Zeina R. Effect of a pharmacist-managed culture review process on antimicrobial therapy in an emergency department. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(10):916–9.

Dumkow LE, Kenney RM, MacDonald NC, Carreno JJ, Malhotra MK, Davis SL. Impact of a multidisciplinary culture follow-up program of antimicrobial therapy in the emergency department. Infect Dis Ther. 2014;3(1):45–53.

Zhang X, Rowan N, Pflugeisen BM, Alajbegovic S. Urine culture guided antibiotic interventions: a pharmacist driven antimicrobial stewardship effort in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(4):594–8.

Acknowledgements

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. This material is based upon work supported, in part, by the Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. T.T.T. and A.R.C. had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures

Tristan T. Timbrook has received honorarium as a speaker and/or advisor for BioFire Diagnostics and GenMark Diagnostics. Aisling R. Caffrey has received research funding from Pfizer, Cubist (Merck), The Medicines Company. Kerry L. LaPlante has received research funding or honorarium as an advisor for Cubist (Merck), BARD/Davol, Biomerieux, Forest (Allergan), Ocean Spray, The Medicines Company, Cempra, and Pfizer. Anais Ovalle, Maya Beganovic, William Curioso, and Melissa Gaitanis have no disclosures to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Research and Development Committee of the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center. This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/21CCF0602A2CA2C3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Timbrook, T.T., Caffrey, A.R., Ovalle, A. et al. Assessments of Opportunities to Improve Antibiotic Prescribing in an Emergency Department: A Period Prevalence Survey. Infect Dis Ther 6, 497–505 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-017-0175-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-017-0175-9