Abstract

Introduction

Hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections remain one of the leading causes of preventable patient mortality in the US. Eradication of MRSA through decolonization could prevent both MRSA infections and transmission; however, there is currently no consensus within the infectious disease community on the proper role of decolonization in the prevention of infections. The purpose of this study was to assess the impact of decolonization with mupirocin on subsequent MRSA carriage.

Methods

Patients included in this study were those with an inpatient admission to a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2009 who had a positive MRSA screen on admission and a subsequent re-admission during the same time period. Exposure to mupirocin on the initial hospital admission was measured using Barcode Medication Administration data and MRSA carriage was measured using microbiology text reports and lab data containing results from surveillance swabs collected from the nares. Chi-square tests were used to test for differences in re-admission MRSA carriage rates between mupirocin-receiving and non-mupirocin-receiving patients.

Results

Of the 25,282 MRSA-positive patients with a subsequent re-admission included in the present study cohort, 1,183 (4.7%) received mupirocin during their initial hospitalization. Among the patients in the present study cohort who were re-admitted within 30 days, those who received mupirocin were less likely to test positive for MRSA carriage than those who did not receive mupirocin (27.2% vs. 55.1%, P < 0.001). The proportion of those who tested positive for MRSA during re-admissions that occurred 30–60 days, 60–120 days, and >120 days were 33.9, 37.3, and 41.0%, respectively, among mupirocin patients and 52.7%, 53.0%, and 51.9%, respectively, for patients who did not receive mupirocin (P < 0.001 at each time point).

Conclusion

Patients decolonized with mupirocin in VA hospitals were less likely to be colonized with MRSA on re-admission as long as 4 months after decolonization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nearly 5% of all patients admitted to a hospital in the US develop a hospital-acquired infection (HAI) [1], and close to 20% of these infections are fatal [2]. HAI prevention has received a great deal of attention in recent national legislation aimed at reducing healthcare costs [1, 3], and more than 15 states already have legislative mandates requiring either reporting or screening of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), one of the most virulent and common HAIs [4]. Despite this considerable attention, hospital-acquired MRSA infections remain a major cause of preventable hospital mortality in the US [2].

Roughly 20% of healthy individuals are consistently colonized with Staphylococcus aureus, while another 30% are intermittently colonized [5]. Although many MRSA carriers remain asymptomatic, carriage does increase the risk of MRSA infection and can be transmitted to other individuals [5]. There is controversy over the proper role of MRSA decolonization in the prevention of MRSA infections, though some advocate for a policy of decolonization [6]. Support for institutionalizing the practice of decolonization is based on the presumption that MRSA eradication can lower the risk of subsequent MRSA infection and may decrease transmission to other individuals. MRSA decolonization with the topical agent, mupirocin, has not been widely practiced for several reasons, including concern that widespread use could lead to resistance [7, 8], uncertainty surrounding mupirocin’s decolonizing efficacy [9], and the absence of an endorsement of this strategy in national guidelines.

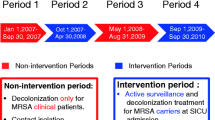

Since October 2007, universal nasal surveillance with contact isolation for patients who screen positive for MRSA has been standard procedure across Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals [10]. Some facilities also choose to decolonize patients, although it is not required or encouraged as part of VA policy. The purpose of the present study was to assess the impact of decolonization on subsequent MRSA carriage in a cohort of patients admitted to any of 111 VA hospitals across the US. The authors hypothesized that use of mupirocin would be associated with a reduced probability of subsequent MRSA carriage.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board and the VA Salt Lake City Office of Research.

Subjects

Patients included in this study were those with an inpatient admission to a VA hospital between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2009 who had a positive MRSA screen on admission and a subsequent re-admission during the same time period.

Exposure and Outcome Variables

The exposure of interest in this study was treatment with mupirocin, a topical agent applied nasally, for MRSA decolonization. Patients were classified as having been exposed to decolonization if mupirocin was ordered or dispensed for the patient during their initial inpatient stay. The outcome in this study was subsequent MRSA carriage, as measured by surveillance swabs collected from the nares. The authors measured this at four time periods (<30, 30–60, 60–120, and >120 days), using each patient’s MRSA screening test result at the time of first re-admission.

Data

The authors identified exposure to mupirocin using VA Bar Code Medication Administration (BCMA) data. BCMA captures inpatient medication administration throughout all VA hospitals using scanned barcode labels [11]. Natural language processing was used to identify positive MRSA tests from semi-structured microbiology text reports and structured lab data containing results from MRSA surveillance tests [12].

Statistical Analysis

The authors used a Chi-square test to test for differences in re-admission MRSA carriage rates between mupirocin-receiving and non-mupirocin-receiving patients at each re-admission time period.

Results

A total of 25,282 MRSA positive patients with a subsequent re-admission were included in the present study cohort (Fig. 1). Of these, 1,183 (4.7%) received mupirocin during their initial hospitalization. Among the patients in the present study cohort who were re-admitted within 30 days, those who received mupirocin were less likely to test positive for MRSA carriage than those who did not receive mupirocin (27.2% vs. 55.1%, P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The percentage of those who tested positive for MRSA during re-admissions that occurred between 30–60, 60–120, and >120 days were 33.9%, 37.3%, and 41.0%, respectively, among mupirocin patients and 52.7%, 53.0%, and 51.9%, respectively, for patients who did not receive mupirocin (P < 0.001 at each time point).

Discussion

The results of present study showed that patients who receive mupirocin for decolonization of MRSA carriage may be less likely to have MRSA carriage on re-admission to the hospital. Comprising more than 25,000 patients from over 100 VA hospitals across the US, this study is by far the largest study to assess the effect of mupirocin on subsequent MRSA carriage.

The finding that decolonization may lead to reduced risk of MRSA carriage over a prolonged period of time has important implications for patient safety efforts. Frequent re-admissions of MRSA-colonized patients are associated with increased colonization pressure and contribute to the endemicity of MRSA [13, 14]. Successful eradication of MRSA through decolonization could lead to decreased importation, reduced MRSA acquisitions, and fewer infections.

The results from the present study are similar to those seen in other studies. A study of three Chicago-area hospitals found that, regardless of the number of doses received, patients treated with mupirocin were less likely to have persistent colonization than those not treated with mupirocin [15]. The effects of decolonization are believed to last up to 90 days; however, few studies have followed patients for longer periods of time [16]. Exceptions to this include two studies of decolonization in patients in long-term care facilities. Mody et al. [17] found that 61% of patients remained decolonized for up to 90 days, with some remaining decolonized for up to 6 months. Simor et al. [18] reported statistically significant differences in recolonization rates between decolonized and non-decolonized patients at 8 months.

Reflecting the debate over widespread administration of mupirocin, less than 5% of VA study subjects from the present study received mupirocin, whereas another study surveying 674 infectious disease physicians reported much higher rates of decolonization among surgical patients [19]. There are many possible explanations for these differences, including differences in patients (surgical vs. all admitted patients) and method of data collection (self-reported survey vs. secondary data from medical records).

The present study had several limitations. First, the outcome of the study was MRSA carriage, and not MRSA infection, which is the more important outcome from a clinical standpoint. Future research is needed to evaluate the effect of mupirocin on MRSA infection. Second, because the authors conducted this study using secondary data, the authors were not able to prospectively test patients for recolonization at various time points after the initial decolonization. The authors, therefore, had to select patients who were re-admitted to a VA facility in order to capture subsequent colonization. While this method of selecting study subjects has been employed in other studies [15], it is possible that conditioning on the common effect of having a re-admission could introduce selection bias if re-admission rates differ between mupirocin-receiving and non-mupirocin-receiving patients [20]. Notably, of the 55,761 non-mupirocin-receiving patients and 2,788 mupirocin-receiving patients who tested positive for MRSA, 43.2% and 42.4% (P = 0.413) had a re-admission, respectively; these similar re-admission rates between the two groups of patients suggest that selection bias is not a substantial problem in the present study. Finally, chlorhexidine bathing is another commonly used decolonization technique that may be used separately or in conjunction with mupirocin [21]. Unfortunately, it is not possible to identify chlorhexidine through VA BCMA data, so the authors were not able to explore the effect of different decolonization techniques.

In conclusion, mupirocin was negatively associated with MRSA carriage more than 4 months after use in MRSA carriers admitted to a VA hospital. These long-term effects may provide important protection from MRSA infections. In light of these findings, the authors reiterate the call for large-scale trials, in conjunction with screening and isolation, to evaluate decolonization as a tool for reducing nosocomial MRSA infections [22, 23].

References

Graves N, McGowan JE Jr. Nosocomial infection, the Deficit Reduction Act, and incentives for hospitals. JAMA. 2008;300:1577–9.

Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) MRSA Investigators, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–71.

Kocher R, Emanuel EJ, DeParle NA. The Affordable Care Act and the future of clinical medicine: the opportunities and challenges. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:536–9.

Wise ME, Weber SG, Schneider A, et al. Hospital staff perceptions of a legislative mandate for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus screening. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:573–8.

Wertheim HF, Melles DC, Vos MC, et al. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:751–62.

Ammerlaan HS, Kluytmans JA, Berkhout H, et al. Eradication of carriage with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: effectiveness of a national guideline. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2409–17.

Miller MA, Dascal A, Portnoy J, Mendelson J. Development of mupirocin resistance among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after widespread use of nasal mupirocin ointment. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1996;17:811–3.

Simor AE, Stuart TL, Louie L, et al. Mupirocin-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in Canadian hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3880–6.

Loeb M, Main C, Walker-Dilks C, Eady A. Antimicrobial drugs for treating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD003340.

Jain R, Kralovic SM, Evans ME, et al. Veterans Affairs initiative to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1419–30.

Huttner B, Jones M, Rubin MA, et al. Double trouble: how big a problem is redundant anaerobic antibiotic coverage in Veterans Affairs medical centres? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:1537–9.

Jones M, DuVall S, Spuhl J, Samore M, Nielson C, Rubin M. Identification of methicillin-resistant Stahylococcus aureus within the Nation’s Veteran Affairs Medical Centers using natural language processing. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:34.

Cooper BS, Medley GF, Stone SP, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitals and the community: stealth dynamics and control catastrophes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10223–8.

Bootsma MC, Diekmann O, Bonten MJ. Controlling methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: quantifying the effects of interventions and rapid diagnostic testing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5620–5.

Robicsek A, Beaumont JL, Thomson RB Jr, Govindarajan G, Peterson LR. Topical therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization: impact on infection risk. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:623–32.

Bradley SF. Eradication or decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage: what are we doing and why are we doing it? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:186–9.

Mody L, Kauffman CA, McNeil SA, Galecki AT, Bradley SF. Mupirocin-based decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus carriers in residents of 2 long-term care facilities: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1467–74.

Simor AE, Phillips E, McGeer A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of chlorhexidine gluconate for washing, intranasal mupirocin, and rifampin and doxycycline versus no treatment for the eradication of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:178–85.

Diekema D, Johannsson B, Herwaldt L, et al. Current practice in Staphylococcus aureus screening and decolonization. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:1042–4.

Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15:615–25.

Batra R, Cooper BS, Whiteley C, Patel AK, Wyncoll D, Edgeworth JD. Efficacy and limitation of a chlorhexidine-based decolonization strategy in preventing transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:210–7.

Coates T, Bax R, Coates A. Nasal decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus with mupirocin: strengths, weaknesses and future prospects. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:9–15.

Lucet JC, Regnier B. Screening and decolonization: does methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus hold lessons for methicillin-resistant S. aureus? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:585–90.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Jeffrey Scehnet, Patricia Nechodom, and Kevin Nechodom for their assistance in acquiring the data used in this study. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Kristin Knippenberg. Dr. Nelson was supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute grant 1 KM1CA156723, and the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director grant\5TL1RR025762-03. Dr. Nelson is the guarantor for this article, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial interests to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nelson, R.E., Jones, M. & Rubin, M.A. Decolonization with Mupirocin and Subsequent Risk of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Carriage in Veterans Affairs Hospitals. Infect Dis Ther 1, 1 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-012-0001-3

Received:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-012-0001-3