Abstract

Background

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is an autosomal recessive neuromuscular disease characterized by progressive muscle weakness and atrophy. Clinical trial data suggest early diagnosis and treatment are critical. The purpose of this study was to evaluate neurology appointment wait times for newborn screening identified infants, pediatric cases mirroring SMA symptomatology, and cases in which SMA is suspected by the referring physician. Approaches for triaging and expediting referrals in the US were also explored.

Methods

Cure SMA surveyed healthcare professionals from two cohorts: (1) providers affiliated with SMA care centers and (2) other neurologists, pediatric neurologists, and neuromuscular specialists. Surveys were distributed directly and via Medscape Education, respectively, between July 9, 2020, and August 31, 2020.

Results

Three hundred five total responses were obtained (9% from SMA care centers and 91% from the general recruitment sample). Diagnostic journeys were shorter for infants eventually diagnosed with SMA Type 1 if they were referred to SMA care centers versus general sample practices. Appointment wait times for infants exhibiting “hypotonia and motor delays” were significantly shorter at SMA care centers compared to general recruitment practices (p = 0.004). Furthermore, infants with SMA identified through newborn screening were also more likely to be seen sooner if referred to a SMA care center versus a general recruitment site. Lastly, the majority of both cohorts triaged incoming referrals. The average wait time for infants presenting at SMA care centers with “hypotonia and motor delay” was significantly shorter when initial referrals were triaged using a set of “key emergency words” (p = 0.036).

Conclusions

Infants directly referred to a SMA care center versus a general sample practice were more likely to experience shorter SMA diagnostic journeys and appointment wait times. Triage guidelines for referrals specific to “hypotonia and motor delay” including use of “key emergency words” may shorten wait times and support early diagnosis and treatment of SMA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to modifying the rapid and irreversible loss of motor neurons in patients affected by spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) Type 1 |

Healthcare providers in the US were surveyed to evaluate average neurology appointment wait time from initial referral to first consult and to assess current approaches for triaging and expediting referrals when SMA is suspected |

What was learned from the study? |

For cases in which SMA was suspected by the referring physician, as well as for newborn screening referrals, wait times were shorter when infants were referred to a care center specializing in SMA versus a neurology, pediatric neurology, or neuromuscular practice that did not specialize in SMA |

The development of referral triage guidelines for treatable pediatric conditions involving hypotonia and motor delays and updated guidelines detailing practice considerations both for SMA newborn screening management may standardize provider approach and optimize patient outcomes |

Introduction

SMA Overview

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), an autosomal recessive neuromuscular disease characterized by progressive muscle weakness and atrophy, affects approximately 1 in 11,000 infants in the US each year [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Without disease-modifying therapy, SMA progressively impacts an individual’s strength, muscle function, respiration, and ability to independently perform activities of daily living. Until the recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of three treatment options, SMA was the leading genetic cause of death in children under the age of 2 years [5, 8, 9].

The severity of SMA is largely correlated with the copy number of SMN2 (spinal motor neuron protein), a paralogue of the SMN1 gene, which produces only 5–10% functional SMN protein; having more copies of SMN2 is typically associated with a less severe clinical phenotype [10, 11]. SMA is traditionally classified into four primary clinical phenotypes (Types 1–4) based upon the age of symptom onset (which correlates with disease severity and survival) and the highest motor function milestone achieved [11,12,13,14]. The recent availability of treatment, particularly when received prior to symptom onset, has dramatically impacted disease progression and led to a shift in classification based on SMN2 copy number and motor function ability, i.e., non-sitter, sitter, and walker [15].

Three FDA-approved therapies—nusinersen [16] (Spinraza®, an antisense oligonucleotide targeting SMN2 splicing), onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi [17] (Zolgensma®, an SMN1 gene-replacement therapy), and risdiplam [18] (Evrysdi®, a small molecule targeting SMN2 splicing)—have proven effective in modifying the disease among infants, children, and adults with SMA [19,20,21]. Early treatment has been shown to be critical to modifying disease progression, improving health outcomes, and increasing life expectancy for patients with SMA [22,23,24,25,26,27]. In infants affected by SMA Type 1 (the most severe and common form in which symptom onset occurs prior to 6 months of age), diagnostic delays can result in rapid denervation, profound loss of motor function, and increased risk of death before 2 years of age [28,29,30]. This potential to alter the course of SMA based on early diagnosis—ideally, before the onset of symptoms—provided the motivation for the work described in this article [15].

SMA Diagnosis

The diagnosis of SMA is considered a medical emergency. Through the revised consensus statement for SMA [31], pediatric primary care physicians are encouraged to immediately refer patients suspected of SMA to a neurologist or neuromuscular specialist for further evaluation and genetic testing. Despite the recommended standard of care and importance of early diagnosis, diagnostic delays remain prevalent [32,33,34,35].

Newborn Screening

SMA was added to the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) for newborn screening in 2018 [36]. As of January 2024, all 50 states were screening newborns for SMA, culminating in 100% of all US infants being screened at birth [37]. A mutation causing the homozygous deletion of exon 7 of the SMN1 gene is the most common cause of SMA and is readily detected by newborn screening. However, in 3–5% of individuals with SMA, the disease is caused by other point mutations in the SMN1 gene that are not detectable with standard SMN1 genetic testing and will not be identified by newborn screening [38, 39]. As such, even in states that screen for SMA at birth, immediate neurologic evaluation of infants in whom SMA is suspected remains essential.

Potential Factors Contributing to Diagnostic Delays in SMA

Multiple factors may contribute to persisting diagnostic delays in SMA [32,33,34,35]. The complexity of the pediatric-specialty care interface, including delivery deficiencies, and neurologists’ schedules, as well as a lack of adequate health insurance have been previously identified as potential hurdles to patient referrals and management systems [40, 41]. Few studies, however, have examined how factors involved in the interface between pediatricians and neurology specialists—including appointment triage methods, appointment wait times, and triage staff training—may affect and/or contribute to ongoing diagnostic delays for SMA evaluation in the US. In the US, healthcare typically originates with a primary care provider (PCP) who evaluates the patient and determines whether specialized medical care and/or services are required. If so, the PCP will provide the patient with a referral to a specialty care physician. A referral is typically required by both the specialty care physician’s office or service provider and the insurance payer. Barriers in communication among PCPs, specialists, and payers, as well as limited access to specialty care providers and services, can extend referral appointment wait times [40, 42,43,44]. For conditions like SMA that require immediate evaluation by a specialist to determine if emergent treatment is necessary, prolonged wait times for referral appointments can be especially problematic [22,23,24,25,26,27].

In 2019, Cure SMA conducted a survey of general pediatricians (the 2019 General Pediatrician Survey) to better understand referral patterns and other barriers that may contribute to diagnostic delays in SMA [33]. Findings revealed that neurologist appointment wait time is a primary factor in pediatricians’ decisions when generating a referral, with 64.2% of respondents citing wait times of 1–6 months [33]. The objective of the study described here was to better understand pediatric SMA referral delays from the perspective of neurologists and other neuromuscular specialists and to identify current best practices for expediting referrals.

Methods

Survey Development and Distribution

A peer-reviewed literature search of the PubMed database was performed using the search terms “referral triage” or “appointment triage,” “triage practices,” “urgent referral” or “urgent appointment,” and “referral priority” or “appointment priority” alongside the terms “neurology,” “pediatric neurology,” or “child neurology.” Using insights from the resulting literature review, the 2019 General Pediatrician Survey [33], and discussions with SMA nurse coordinators, the authors developed a survey (Appendix A). The survey featured a combination of bivariate and multiple-choice questions formulated to assess the average wait time from initial referral to first visit, the diagnostic odyssey of referral pathways and delays experienced by patients with SMA Type 1, perceived referral barriers, and triage practices utilized at care sites. The survey questions were designed to investigate whether wait time varied with factors such as patient age and whether the referral was initiated based upon the physician’s observation of symptoms, suspicion of SMA, or positive newborn screening. Prior to distribution, the survey was reviewed by SMA nurse coordinators and refined based upon feedback.

Cure SMA distributed the survey in two phases. During the first phase, Cure SMA directly engaged a curated list of 44 physicians (referred to in this paper as the “SMA care center sample”). The curated list included principal investigators within the Cure SMA Care Center Network and program leads at other well-known SMA research or treatment centers. One individual from each site was invited to participate. The Cure SMA Care Center Network is a collaboration of 29 nationwide medical institutions in the US whose mission it is to develop an evidence-based standard of care for SMA, educate other healthcare providers about the disease and care, and collect real world data on the disease and treatment [45]. At the time of the survey, the Cure SMA Care Center Network included 19 sites. In the second phase, the survey was distributed in partnership with Medscape Education to a broad range of neurologists, child neurologists, and neuromuscular specialists (referred to in this paper as the “general recruitment sample”). Eligibility criteria for this phase included a requirement that respondents evaluate pediatric patients. The response rate for the general recruitment sample was 3.72% from the Medscape Education panel. Due to the established enrollment goal for this phase, Medscape Education utilized two external recruitment partners to support distribution to eligible physicians. Medscape Education reviewed the data obtained from external recruitment partners to remove duplicate responses. The response rate from those efforts is not available. Responses were fielded for both cohorts from July 9, 2020, through August 31, 2020. All participants received a $60 gift card as compensation for their time.

Ethical Approval

Prior to distribution, WIRB-Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board (WCG IRB) determined that the study was exempt from full IRB review and granted a consent waiver. All respondents were informed via the Cure SMA privacy policy that findings may be published. Only aggregate results are included within the manuscript. All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Statistical Analyses

Assessment of survey responses provided an opportunity to compare length of appointment wait times and variability of factors contributing to those wait times among the general recruitment sample of providers and the curated set of providers connected to SMA care centers. Descriptive statistics (numbers and percentages) were used for categorical outcomes. Chi-square tests of independence were used to determine whether there was an association between the triage method for prioritizing referrals and the average wait time from referral to the first appointment in each cohort. Logistic regressions were used to determine which triage methods and staff personnel referrals impacted wait time.

Results

Respondent Demographics

Three hundred five total responses were obtained, 279 (91.5%) from the general recruitment sample among a broad range of providers and an additional 26 (8.5%) from the SMA care center sample. Among the general recruitment sample, 35.5% of respondents identified as adult neurologists, 28.7% as neuromuscular specialists, 7.5% as pediatric neurologists, and 28.3% as neurogeneticists. For the SMA care center sample, 7.7% of respondents identified as adult neurologists, 57.7% as neuromuscular specialists, 30.8% as pediatric neurologists, and 3.9% as neurogeneticists (Table 1).

Of all respondents across both cohorts, the majority (182/305) practiced in urban settings; 42.3% (129/305) of respondents indicated they are academic faculty; 81.3% (248/305) indicated they see > 25 patients a week, and 27.2% (83/305) saw > 75 patients per week.

Diagnostic Odyssey

Arriving at a diagnosis of SMA often takes patients and their families through a long and burdensome diagnostic odyssey that involves multiple consultations with various healthcare providers. This study provided further insights into a key aspect of that process by evaluating the numbers of providers patients saw prior to receiving a confirmed diagnosis of SMA. Among the general recruitment sample, 39.1% of respondents indicated that, in > 20% of suspected cases of SMA Type 1, they were the first specialist (neurologist, pediatric neurologist, or neuromuscular specialist) to evaluate the patient prior to confirmatory diagnosis (Fig. 1). For cases in which the respondent was not the first specialist to evaluate patients for symptoms that resulted in a diagnosis of SMA Type 1, 19.2% indicated that on average the patients had previously seen three or more providers; 50.0% of respondents indicated the average diagnostic delay for SMA Type 1 patients, in which the respondent was not the first to complete evaluation prior to diagnosis, was > 2 months.

Reported diagnostic journey of SMA Type 1 patients amongst general recruitment sample. a Percent (%) of cases in which survey respondent was the first neurologist/pediatric neurologist/neuromuscular specialist to evaluate the patient prior to diagnosis with SMA Type 1; b average number of providers SMA Type 1-affected patient previously saw in which survey participant was not the first to complete evaluation since symptom onset; c average diagnostic delay for SMA Type 1-affected patients in which survey participant was not the first to complete evaluation since symptom onset. SMA spinal muscular atrophy

Conversely, among the SMA care center sample, 73.1% of respondents indicated that, in > 20% of suspected cases of SMA Type 1, they were the first specialist (neurologist, pediatric neurologist, or neuromuscular specialist) to evaluate the patient prior to diagnosis (Fig. 2). For cases in which the respondent was not the first specialist to evaluate patients for symptoms that resulted in a diagnosis of SMA Type 1, 8.0% indicated that on average the patients had previously seen three or more providers; 28.0% of respondents indicated that the average diagnostic delay for SMA Type 1-affected patients for which the survey respondent was not the first to complete evaluation prior to diagnosis was > 2 months (Fig. 2).

Reported diagnostic journey of SMA Type 1 patients among SMA care center sample. a Percent (%) of cases in which survey respondent was the first neurologist/pediatric neurologist/neuromuscular specialist to evaluate the patient with SMA Type 1 prior to diagnosis; b average number of providers SMA Type 1-affected patient previously saw in which survey participant was not the first to complete evaluation since symptom onset; c average diagnostic delay for SMA Type 1 affected patients in which survey participant was not the first to complete evaluation since symptom onset. SMA spinal muscular atrophy

Appointment Wait Times

For the purposes of this study, “average wait time” refers to the time between the initial referral by a primary physician and the time of the first appointment with a specialist. Given the significance of early diagnosis and prompt initiation of disease-modifying treatment to improve outcomes for SMA patients—especially those with infantile presentation—the shortest average wait time (0–2 weeks) is optimal.

Within the general recruitment and the SMA care center samples, 81.4% and 84.6% of respondents indicated that the average wait time for all referrals was > 2 weeks, respectively (Table 2). However, the reported proportion of infants presenting with “hypotonia and motor delays” who experienced a wait time of ≤ 2 weeks vs > 2 weeks was significantly different (p = 0.03) between the two cohorts. Specifically, 61.5% of infants presenting with “hypotonia and motor delays” at the SMA care centers were seen within 2 weeks vs 39.1% in the general recruitment sample. Similarly, for cases in which SMA was suspected by the referring physician (“suspected SMA”), the reported proportion of patients who experienced a wait time of ≤ 2 weeks vs > 2 weeks was significantly different (p = 0.004) between the cohorts. Whereas 84.6% of “suspected SMA” cases were seen within 2 weeks at the SMA care centers, only 43.0% in the general recruitment sample were seen within that time frame.

Newborn Screening

The average wait time for referrals of infants identified via newborn screening was also assessed. Among the general recruitment sample, 48.0% reported an average appointment wait time of 0–2 weeks, and 28.3% reported an average wait time of > 2 weeks, with five respondents (1.8%) indicating an average appointment wait time of 3–6 months. All SMA care center respondents that received referrals from newborn screening reported an average wait time of 0–2 weeks (Table 3). The survey was fielded from July 9, 2020, through August 31, 2020. As of July 9, 2020, 31 states had included SMA within newborn screening panels. However, during the survey period, an additional state implemented SMA newborn screening, bringing the total to 32 screening states covering 67.4% of US newborns [37].

Other Factors Impacting Appointment Wait Time for SMA Evaluation

Respondents were asked about general factors that impacted appointment wait time for cases in which SMA was suspected by the referring physician; response options provided included “patient age,” “age of symptom onset,” “family history of SMA,” “severity of symptoms,” and other factors. When provided the option to “select all that apply,” the top two factors cited by respondents within the general recruitment sample were “severity of symptoms” (81.0%) and “patient age” (67.0%). Within the SMA care center sample, “patient age” was cited by 76.9% of respondents, while “age of symptom onset” was cited by 65.4% of respondents.

Participants were asked to rank specific referral barriers, with a focus on ranking frequency (from “Always” to “Never”) with which a list of factors contributed to lengthening appointment wait time. The total number of barriers identified as “Always” and “Usually” were combined and subsequently ranked. Within the general recruitment sample, the top two referral barriers contributing to appointment wait time were “clinician availability/clinic hours” (35.1%) and “restrictions on providers’ options due to insurance” (32.3%). “Clinician availability/clinic hours” (15.4%) and “restrictions on providers’ options due to insurance” (15.4%) were also identified as top barriers among the SMA care center sample.

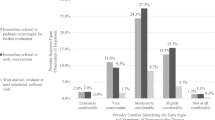

Triage Methods

Survey participants were asked about the triage methods utilized to screen and prioritize incoming appointment referrals in their practices; 84.6% of general recruitment sample respondents and 100% of SMA care center respondents indicated that they triage incoming referrals in some capacity; 57.7% of physicians at SMA care centers and 43.6% of the general recruitment sample said they directly review incoming referrals to expedite urgent cases (Table 4). Additionally, 46.2% of SMA care center respondents said they utilize “centralized call center staff,” and 38.5% rely on “nurse coordinators” to prioritize appointments when key emergency words appear within the referral (Table 4). Respondents within the general recruitment sample indicated that they utilize these triage methods at a lower rate; 22.0% of respondents directly review and prioritize appointments based upon the inclusion of key emergency words, and 18.2% assign front desk staff to complete the task. Logistic regressions were used to evaluate whether triage method and the staff member assignment impacted referral wait time (≤ 2 weeks vs > 2 weeks). The analysis revealed that infants presenting with “hypotonia and motor delays” were more likely to have shorter wait times (2 weeks or less vs longer than 2 weeks) at SMA care centers utilizing nurses/nurse coordinators to triage referrals based upon the inclusion of “key emergency words” (OR = 11.6, p = 0.036). No additional significant associations were identified.

Provider Awareness

To evaluate SMA awareness among physicians in the general recruitment sample, respondents were asked to identify the testing required to definitively diagnose SMA. A significant majority identified the genetic testing requirement and correctly identified SMN2 copy number as the main factor influencing severity of SMA phenotype (82.8%).

Discussion

Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to modifying the rapid and irreversible loss of motor neurons in patients affected by SMA [46,47,48]. Previously, we surveyed pediatricians to determine factors that from their perspective contributed to diagnostic delays in SMA [33]. The majority of pediatricians surveyed cited prolonged wait times for neurology appointments as a contributing factor [33]. The present study yields insights from the perspective of neurologists and neuromuscular specialists into appointment wait times and referral triage methods as potential contributors to delays in SMA diagnosis and treatment. Results of this survey elucidate differences in the diagnostic journey of infants with a suspected diagnosis of SMA Type 1 depending upon where they were referred. Our findings highlight areas of opportunity for all neurology/neuromuscular healthcare professionals to reduce the time to diagnosis and disease-modifying treatment for infants with SMA.

Diagnostic delays of symptomatic SMA are well documented and significantly impact patient prognosis and quality of life as illustrated by clinical trials and real world data [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30, 35, 46,47,48]. However, the early recognition of SMA symptoms—which include progressive hypotonia, motor delays, and areflexia—may prove challenging [33]. Prolonged wait times at neurology and neuromuscular centers can further contribute to delays post referral. Cure SMA encourages neurologists and neuromuscular specialists to deem referrals for the evaluation of infants with a suspected diagnosis of SMA as urgent and prioritize scheduling within 2 weeks. Data from this study revealed that that SMA care centers are more proficient than general recruitment sites at triaging and expediting the evaluation of pediatric cases in which SMA was suspected by the referring physician and infants with “hypotonia and motor delays” within ≤ 2 weeks. Hypotonia is a nonspecific indicator of both benign conditions and pathologic conditions, including SMA. Causes of hypotonia are myriad, can be genetic or metabolic, and can affect the peripheral or central nervous system [49,50,51]. Therefore, all staff members in a given neurology or neuromuscular practice may not have the knowledge, capacity, or experience required to expeditiously triage referrals for infants presenting with hypotonia [49, 51, 52].

Extensive wait times for appointments at specialty clinics may be further compounded by circumstances in which patients are evaluated by multiple specialists before receiving an accurate diagnosis [32, 34, 35]. In Cure SMA’s prior survey to determine factors that influenced referral patterns from pediatricians [33], 83.5% of respondents indicated that a “specialist’s previous experience treating a suspected condition” was a factor when choosing a neurologist or pediatric neurologist for referral. This may in part explain why, in this survey, SMA care center respondents were more likely than general recruitment respondents to be the first provider to evaluate infants with a suspected diagnosis of SMA Type 1. Infants seen by general recruitment respondents were also more likely than those seen at SMA care centers to have previously seen multiple providers and have longer diagnostic journeys. These results indicate that the time to diagnosis and treatment can be shortened by referring infants with suspected diagnosis of SMA Type 1 directly to centers with prior expertise in SMA evaluation and treatment. However, due to limited access to specialty care, this may not be feasible. Cutrona et al. [49] recently developed a diagnostic module that can be used by pediatricians as an add-on to the standard neonatal neurologic examination when hypotonia and other neuromuscular symptoms are present. A pilot study of this model found that not only was it effective in distinguishing between SMA and other neuromuscular conditions, it was also helpful in detecting SMA in infants with mild clinical symptoms [52]. Resources like these may support narrowing of the differential diagnosis, raise provider suspicion of SMA, and trigger genetic testing more efficiently.

Although newborn screening facilitates early diagnosis of SMA, extensive wait times for evaluation and confirmatory testing can also culminate in treatment delays. This research revealed a wide variance in wait times for newborn screening referrals within the general recruitment sample. These data suggest that the rapid adoption of SMA newborn screening, along with the mounting clinical trial and real-world evidence supporting emergent diagnosis and treatment, has been challenging for providers that do not specialize in SMA care and disease management. Although the consensus recommendation among experts in the US is to provide emergent treatment for infants who are diagnosed with SMA and have one to four copies of SMN2 [53,54,55,56], a time frame for treatment initiation has not been specified. The development of updated guidelines detailing practice considerations for SMA newborn screening management may standardize provider approach and optimize patient outcomes.

When asked to rank factors that affect appointment wait times both the general recruitment sample and the SMA care center sample identified “clinician availability/clinic hours” and “restrictions on providers” as barriers to referral. Previous research has found that disparities in access to specialty care can compound delays in diagnosis and treatment for infants and children for whom timely treatment for SMA and other neurologic diseases is critical [33, 35, 57,58,59]. The results from the present study support these findings and point to additional systemic factors, including limitations caused by insurance coverage and reimbursement issues, that impact referrals including which care center and provider and play a role in creating appointment delays. More work is needed to further clarify and define the root causes of these barriers and implement effective solutions.

Data from this study also provide insight into which triage methods may be effective at expediting incoming SMA referrals. Nearly all general recruitment respondents and all SMA care center respondents indicated that their practices triage incoming referrals in some manner. More SMA care center respondents than general recruitment sample respondents indicated that they used “centralized call center staff” and/or a “nurse/nurse coordinator” to assist in referral triage. Although a large percentage of both general recruitment respondents and SMA care center respondents reported utilizing physicians to review triage referrals, this strategy did not significantly impact appointment wait times. Furthermore, using physician review as the first step in triaging SMA referrals may not be sustainable because of demands on physicians’ time. One compromise may be to use a tiered referral triage system involving initial review for key emergency words by dedicated staff. The use of key emergency words in referrals could trigger a second-tier review by the physician who could then determine whether prioritized scheduling for evaluation and genetic testing is appropriate. In this study, respondents were not asked which key emergency words were used to triage incoming referrals for infants with a suspected diagnosis of SMA. Collaborative research between pediatricians and neurologists/neuromuscular specialists to develop a standardized set of key emergency words may be beneficial to both types of practices as well as to infants with SMA. Recent initiatives in other areas of neurologic and pediatric care have shown that a variety of approaches to urgent appointment triage can reduce appointment wait times [60,61,62,63]. These initiatives did not require expensive or complex changes but were accomplished through concerted efforts to utilize existing resources, such as email and electronic scheduling systems, in innovative ways [60,61,62,63]. Future research should explore opportunities to establish referral triage guidelines for treatable pediatric conditions involving hypotonia and motor delays. The guidelines should aim to encourage the broad, consistent implementation of streamlined referral pathways across neurology and neuromuscular centers within the US, paving the way for expeditious diagnosis and treatment of infants with SMA and other diseases for which emergent intervention is optimal [57].

Taken together, the findings from this survey suggest that immediately referring infants with either a suspected clinical diagnosis of SMA or a positive SMA newborn screening result to an SMA care center can significantly decrease their wait time to be evaluated and treated. However, additional research is required to explore the policies and practices implemented across individual care center sites that may have contributed to these results. As of January 2024, the Cure SMA Care Center Network comprised 29 pediatric and adult healthcare sites that are committed to providing excellent, multi-disciplinary healthcare to persons with SMA [45]. In addition to offering FDA-approved SMA treatments, Cure SMA Care Center Network sites share, review, and analyze patient care information to continuously improve evidence-driven care for individuals with SMA [45].

Continuing education about the early symptoms of SMA, newborn screening for SMA, and the urgency for evaluation and treatment may help to close remaining knowledge gaps in general neurology and neuromuscular practices. Given that study participants reported involving a range of allied health professionals in the screening of referrals, educational opportunities should be extended to all triage team members [64]. This online resource offers a variety of educational resources detailing SMA diagnostic criteria, as well as the latest treatment options and protocols.

Study Limitations

Because the survey was designed to evaluate wait times and triage practices for a specific period in time, the measure was not validated prior to distribution. However, future research should explore the development of a validated tool that can be leveraged for ongoing assessment. Due to the method of recruitment, there was a sampling bias within the research design for this study. Recruitment of SMA care centers occurred via a curated list comprised of Cure SMA Care Center Network [45] sites and other well-known SMA research and treatment centers. Also, although the SMA care center sample is representative of the key opinion leaders within the field, the sample size limited our ability to conduct robust comparative analysis across cohorts. Despite the fact that Medscape Education maintains a robust database of providers within the US, our sample does not fully represent the population of neurologists and neuromuscular specialists, which limits the generalizability of these findings. Furthermore, adult neurologists made up the largest percentage of specialists in the general recruitment sample, which may have impacted results. Providers must independently create an account to access content on Medscape’s platform and complete an additional opt-in process to participate in market research. To achieve the target number of responses, invitations to participate in the survey were distributed by Medscape Education via a batching method to eligible providers, which contributed to the response rate. Finally, we recognize that five respondents indicated wait times of 3–6 months to evaluate patients identified via newborn screening. Due to the limited sample size, additional analysis to identify potential correlating factors could not be performed; contributors to extensive wait times were also not directly explored by the survey.

Conclusions

The learnings from this analysis will support continued efforts to reduce diagnostic delays and alleviate barriers to optimal diagnosis and management of SMA. Study findings, along with additional analysis of sub-group cohorts within the survey data, will also be utilized to promote development of improved screening and referral pathways for the evaluation of hypotonia and suspected SMA within the pediatric population.

While diagnosing and treating patients affected by SMA entails unique challenges, some of the issues confronting this population are similar to those faced by other rare disease groups, particularly those for which early intervention is critical. There is an opportunity to engage in collaborative efforts to address systemic contributors to diagnostic delays by partnering with other organizations within the rare disease and maternal and child health communities.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80(1):155–65.

Arnold WD, Kassar D, Kissel JT. Spinal muscular atrophy: diagnosis and management in a new therapeutic era. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51(2):157–67.

Kolb SJ, Kissel JT. Spinal muscular atrophy: a timely review. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(8):979–84.

Kolb SJ, Kissel JT. Spinal muscular atrophy. Neurol Clin. 2015;33(4):831–46.

Sugarman EA, Nagan N, Zhu H, et al. Pan-ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: clinical laboratory analysis of >72,400 specimens. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(1):27–32.

Wirth B. An update of the mutation spectrum of the survival motor neuron gene (SMN1) in autosomal recessive spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Hum Mutat. 2000;15(3):228–37.

Bergin A, Kim G, Price DL, Sisodia SS, Lee MK, Rabin BA. Identification and characterization of a mouse homologue of the spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene, survival motor neuron. Gene. 1997;204(1–2):47–53.

Prior TW. Carrier screening for spinal muscular atrophy. Genet Med. 2008;10(11):840–2.

Verhaart IEC, Robertson A, Wilson IJ, et al. Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q-linked spinal muscular atrophy—a literature review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):124.

Ogino S, Leonard DG, Rennert H, Ewens WJ, Wilson RB. Genetic risk assessment in carrier testing for spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Med Genet. 2002;110(4):301–7.

Wadman RI, Stam M, Gijzen M, et al. Association of motor milestones, SMN2 copy and outcome in spinal muscular atrophy Types 0–4. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(4):365–7.

Zerres K, Rudnik-Schoneborn S. Natural history in proximal spinal muscular atrophy. Clinical analysis of 445 patients and suggestions for a modification of existing classifications. Arch Neurol. 1995;52(5):518–23.

Russman BS. Spinal muscular atrophy: clinical classification and disease heterogeneity. J Child Neurol. 2007;22(8):946–51.

Piepers S, van den Berg LH, Brugman F, et al. A natural history study of late onset spinal muscular atrophy Types 3b and 4. J Neurol. 2008;255(9):1400–4.

Schorling DC, Pechmann A, Kirschner J. Advances in treatment of spinal muscular atrophy—new phenotypes, new challenges, new implications for care. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2020;7(1):1–13.

Spinraza. Prescribing information. Biogen. https://www.spinraza.com/content/dam/commercial/spinraza/caregiver/en_us/pdf/spinraza-prescribing-information.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2024.

Zolgensma. Prescribing information. Novartis Gene Therapies. https://www.novartis.com/us-en/sites/novartis_us/files/zolgensma.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2024.

Evrysdi. Prescribing information. Genentech. https://www.gene.com/download/pdf/evrysdi_prescribing.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2024.

Mercuri E. Spinal muscular atrophy: from rags to riches. Neuromuscul Disord. 2021;31(10):998–1003.

Aslesh T, Yokota T. Restoring SMN expression: an overview of the therapeutic developments for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. Cells. 2022;11(3):417.

Ravi B, Chan-Cortes MH, Sumner CJ. Gene-targeting therapeutics for neurological disease: lessons learned from spinal muscular atrophy. Annu Rev Med. 2021;72:1–14.

Motyl AAL, Gillingwater TH. Timing is everything: clinical evidence supports pre-symptomatic treatment for spinal muscular atrophy. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3(8): 100725.

Strauss KA, Farrar MA, Muntoni F, et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec for presymptomatic infants with two copies of SMN2 at risk for spinal muscular atrophy type 1: the phase III SPR1NT trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1381–9.

Strauss KA, Farrar MA, Muntoni F, et al. Onasemnogene abeparvovec for presymptomatic infants with three copies of SMN2 at risk for spinal muscular atrophy: the phase III SPR1NT trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(7):1390–7.

McMillan HJ, Kernohan KD, Yeh E, et al. Newborn screening for spinal muscular atrophy: Ontario testing and follow-up recommendations. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021;48(4):504–11.

Lee BH, Waldrop MA, Connolly AM, Ciafaloni E. Time is muscle: a recommendation for early treatment for preterm infants with spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(2):153–5.

Abreu NJ, Waldrop MA. Overview of gene therapy in spinal muscular atrophy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(4):710–20.

Kolb SJ, Coffey CS, Yankey JW, et al. Natural history of infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. Ann Neurol. 2017;82(6):883–91.

Keinath MC, Prior DE, Prior TW. Spinal muscular atrophy: mutations, testing, and clinical relevance. Appl Clin Genet. 2021;14:11–25.

Tizzano EF. Treating neonatal spinal muscular atrophy: a 21st century success story? Early Hum Dev. 2019;138: 104851.

Mercuri E, Finkel RS, Muntoni F, et al. Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: part 1: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care. Neuromuscul Disord. 2018;28(2):103–15.

Butterfield RJ. Spinal muscular atrophy treatments, newborn screening, and the creation of a neurogenetics urgency. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2021;38: 100899.

Curry M, Cruz R, Belter L, Schroth M, Lenz M, Jarecki J. Awareness screening and referral patterns among pediatricians in the United States related to early clinical features of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):236.

Bolaño Díaz CF, Morosini M, Chloca F, et al. The difficult path to diagnosis of the patient with spinal muscular atrophy. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2023;121(2): e202102542.

Pera MC, Coratti G, Berti B, et al. Diagnostic journey in spinal muscular atrophy: is it still an odyssey? PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3): e0230677.

Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Spinal Muscular Atrophy. 2022. https://newbornscreening.hrsa.gov/conditions/spinal-muscular-atrophy. Accessed 9 Sept 2022.

Cure SMA. Newborn Screening for SMA. 2022. Available from https://www.curesma.org/newborn-screening-for-sma/. Accessed 2 Jan 2024.

Bladen CL, Thompson R, Jackson JM, et al. Mapping the differences in care for 5,000 spinal muscular atrophy patients, a survey of 24 national registries in North America, Australasia and Europe. J Neurol. 2014;261(1):152–63.

Jedrzejowska M, Gos M, Zimowski JG, Kostera-Pruszczyk A, Ryniewicz B, Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I. Novel point mutations in survival motor neuron 1 gene expand the spectrum of phenotypes observed in spinal muscular atrophy patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014;24(7):617–23.

Greenwood-Lee J, Jewett L, Woodhouse L, Marshall DA. A categorisation of problems and solutions to improve patient referrals from primary to specialty care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):986.

Baxter SK, Blank L, Woods HB, Payne N, Rimmer M, Goyder E. Using logic model methods in systematic review synthesis: describing complex pathways in referral management interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:62.

Bohnhoff JC, Guyon-Harris K, Schweiberger K, Ray KN. General and subspecialist pediatrician perspectives on barriers and strategies for referral: a latent profile analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23(1):576.

Bohnhoff JC, Taormina JM, Ferrante L, Wolfson D, Ray KN. Unscheduled referrals and unattended appointments after pediatric subspecialty referral. Pediatrics. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0545.

Timmins L, Kern LM, O’Malley AS, Urato C, Ghosh A, Rich E. Communication gaps persist between primary care and specialist physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2022;20(4):343–7.

Cure SMA. Cure SMA Care Center Network. 2022. Available from: https://www.curesma.org/sma-care-center-network/. Accessed 9 Sept 2022.

Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1723–32.

Mendell JR, Al-Zaidy S, Shell R, et al. Single-dose gene-replacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(18):1713–22.

De Vivo DC, Bertini E, Swoboda KJ, et al. Nusinersen initiated in infants during the presymptomatic stage of spinal muscular atrophy: interim efficacy and safety results from the Phase 2 NURTURE study. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29(11):842–56.

Cutrona C, Pede E, De Sanctis R, et al. Assessing floppy infants: a new module. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181(7):2771–8.

Mercuri E, Pera MC, Brogna C. Neonatal hypotonia and neuromuscular conditions. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;162:435–48.

Morton SU, Christodoulou J, Costain G, et al. Multicenter consensus approach to evaluation of neonatal hypotonia in the genomic era: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(4):405–13.

Pane M, Donati MA, Cutrona C, et al. Neurological assessment of newborns with spinal muscular atrophy identified through neonatal screening. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181(7):2821–9.

Glascock J, Sampson J, Connolly AM, et al. Revised recommendations for the treatment of infants diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy via newborn screening who have 4 copies of SMN2. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2020;7(2):97–100.

Glascock J, Sampson J, Haidet-Phillips A, et al. Treatment algorithm for infants diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy through newborn screening. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2018;5(2):145–58.

Kemper AR, Lam KK. Review of newborn screening implementation for spinal muscular atrophy final report 2020.

Prior TW, Leach ME, Finanger E, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy. In: Adam MP, Pagon RA, et al., editors. Genereviews. WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 2020.

Shellhaas RA, deVeber G, Bonkowsky JL, Child Neurology Society Research C. Gene-targeted therapies in pediatric neurology: challenges and opportunities in diagnosis and delivery. Pediatr Neurol. 2021;125:53–7.

Cao Y, Cheng M, Qu Y, et al. Factors associated with delayed diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy in China and changes in diagnostic delay. Neuromuscul Disord. 2021;31(6):519–27.

D’Silva AM, Kariyawasam DST, Best S, Wiley V, Farrar MA, Group NSNS. Integrating newborn screening for spinal muscular atrophy into health care systems: an Australian pilot programme. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022;64(5):625–32.

Vora SS, Buitrago-Mogollon TL, Mabus SC. A quality improvement approach to ensuring access to specialty care for pediatric patients. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2022;7(3): e566.

Rea CJ, Wenren LM, Tran KD, et al. Shared care: using an electronic consult form to facilitate primary care provider-specialty care coordination. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(7):797–804.

Patterson V, Humphreys J, Henderson M, Crealey G. Email triage is an effective, efficient and safe way of managing new referrals to a neurologist. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(5): e51.

Mohamed K, Al Houri B, Ibrahim K, Khair AM. Improving access for urgent patients in paediatric neurology. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u209266.w4648.

Cure SMA. SMArt Moves. 2022. https://smartmoves.curesma.org/. Accessed 9 Sept 2023.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance.

The authors wish to thank Wendy K.D. Selig of WSCollaborative for her science writing support and Jessica Tingey of Cure SMA for her editorial support.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the Cure SMA Industry Collaboration (SMA-IC) for the funding support to conduct this research study. The SMA-IC was established in 2016 to leverage the experience, expertise, and resources of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, as well as other nonprofit organizations involved in the development of SMA therapeutics to more effectively address a range of scientific, clinical, and regulatory challenges. Current members include Cure SMA, Biogen, Scholar Rock, Novartis Gene Therapies, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Epirium Bio, Genentech/Roche, and SMA Europe. Funding for this research was provided by members of the 2020 SMA-IC, which included Genentech/Roche, Novartis Gene Therapies, Biogen, Cytokinetics, and Scholar Rock. The Rapid Service Fee for this publication, and payment to the WSCollaborative for writing assistance, were paid through funding provided by the SMA-IC Collaboration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mary Curry conceptualized and designed the study, developed resources, supervised data curation, analyzed data, and contributed to the initial draft of the manuscript. Rosángel Cruz conceptualized and supervised study design and data collection, developed resources, and critically reviewed the manuscript, providing important intellectual input. Lisa Belter analyzed data and critically reviewed the manuscript, providing important intellectual input. Mary Schroth contributed to conceptualization and study design, developed resources, and critically reviewed the manuscript, providing important intellectual input. Jill Jarecki conceptualized and supervised study design and data collection, developed resources, and critically reviewed the manuscript, providing important intellectual input. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jill Jarecki was an employee of Cure SMA at the time of this study and is currently an employee of BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Rosángel Cruz was an employee of Cure SMA at the time of this study; the author has nothing to disclose. Mary Curry, Lisa Belter, and Mary Schroth have nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Prior to distribution, WIRB-Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board (WCG IRB) determined that the study was exempt from full IRB review and granted a consent waiver. All respondents were informed via the Cure SMA privacy policy that findings may be published. Only aggregate results are included within the manuscript. All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Prior Presentation: Aspects of this work have previously been presented virtually at the 2021 MDA Clinical and Scientific Conference, March 15–18, 2021; the 73rd AAN Annual Meeting, April 17–22, 2021; and the 25th International Annual Congress of the World Muscle Society, September 20–24, 2021.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Curry, M.A., Cruz, R.E., Belter, L.T. et al. Assessment of Barriers to Referral and Appointment Wait Times for the Evaluation of Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA): Findings from a Web-Based Physician Survey. Neurol Ther 13, 583–598 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-024-00587-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-024-00587-9