Abstract

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative disease that affects memory, thinking, and behavior and places a substantial economic burden on caregivers and healthcare systems. This early-phase study aimed to model lecanemab, a humanized monoclonal antibody targeting amyloid protofibrils, for patients with early AD, and estimate the potential value-based price (VBP) of lecanemab + standard of care (SoC) compared to SoC alone given an expected product profile of lecanemab informed by data from a phase II trial from payer and societal perspectives using a broad range of willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds in the USA.

Methods

A disease simulation model was used to capture how key AD pathology components relate to the clinical and economic presentation of AD. The effects of disease modification and early intervention on disease progression were simulated on the basis of BAN2401-G000-201 trial data as well as published literature. Model outcomes included patient and caregiver quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), total life years, and total care costs including direct medical and non-medical costs for healthcare resource use and indirect costs for caregiving over a lifetime horizon.

Results

Lecanemab + SoC was predicted to result in a gain of 0.61 QALYs (societal, 0.64) and a $8707 decrease in total non-treatment costs (societal, $11,214) vs. SoC alone for patients with early AD. For a WTP threshold range of $50,000 to $200,000 per QALY gained, the potential annual VBP of lecanemab was estimated at $9249 (societal, $10,400) to $35,605 (societal, $38,053), respectively. Other patient subsets, treatment stopping rules, and dosing regimens were used to assess the sensitivity of the VBP estimates.

Conclusion

The early model predicted that lecanemab would potentially improve long-term health outcomes and reduce formal and informal care costs, resulting in a range of VBPs that reflect the value of lecanemab to society.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) places a substantial economic burden on caregivers and healthcare systems. |

This study uses an established disease simulation model that has been validated against a well-known external AD data set (National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center-Uniform Data Set) to estimate the potential value-based price of lecanemab + standard of care (SoC) vs. SoC alone over a broad range of willingness-to-pay thresholds recommended by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. |

Efficacy data for lecanemab was informed by the phase IIb proof-of-concept trial (Study 201) in subjects with early AD; the ongoing phase III trial of lecanemab may refine the findings of this study. |

Patients treated with lecanemab + SoC experienced slower disease progression than those treated with SoC alone, translating into additional life years and quality-adjusted life years gained over a lifetime. |

Predicted health and cost outcomes, along with other considerations, help determine the price and provide a foundation for healthcare decision-makers to understand the potential clinical and socioeconomic value of lecanemab. |

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative disease that affects memory, thinking, and behavior. It is the most common cause of dementia and the fifth-leading cause of death among older populations [1]. AD places a substantial economic burden on caregivers and healthcare systems. Most patients with AD and related dementias receive informal care from family or friends totaling more than 18 billion hours of unpaid care valued at $244 billion [2]. The 2020 direct costs of caring for people with AD in the USA were estimated at $305 billion, with $206 billion paid by Medicare and Medicaid [2].

Recent clinical trials are focusing on disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) to produce an enduring change in the clinical progression of AD by interfering with the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of the disease process, often through primary or intermediate mechanisms such as effects on amyloid or tau [3]. Aducanumab, a monoclonal antibody directed at beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration under the accelerated approval pathway for AD [4]. A recent study by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) assessed the long-term cost-effectiveness and value-based price (VBP) of aducanumab for patients with early AD. Based on its assessment, the annual price for aducanumab to meet commonly used cost-effectiveness thresholds in the USA (i.e., $100,000 and $150,000 per quality-adjusted life year [QALY]) ranged from $2950 to $8360 [5]. The VBP estimates from this assessment reflected in part the uncertainty in aducanumab efficacy stemming from discordant phase III trial results [6].

Lecanemab is a humanized, monoclonal antibody targeting amyloid protofibrils for the treatment of AD. It has been studied in the BAN2401-G000-201 trial (Study 201; NCT01767311) [7] and in an ongoing phase III clinical trial (CLARITY AD; NCT03887455) [8]. Study 201 was a randomized, double-blinded, phase II trial that assessed the efficacy and safety of lecanemab vs. placebo using a Bayesian adaptive design with response adaptive randomization. The study evaluated 856 patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD and mild AD dementia who were amyloid positive. Statistical significance was achieved on key efficacy endpoints after 18 months in patients receiving 10 mg/kg biweekly compared with placebo. Endpoints included the reduction of amyloid by positron emission tomography (PET) standard uptake value ratio (SUVr) accumulated in the brain (− 0.30 adjusted mean change from baseline) and slowing progression in key cognition scales (AD Composite Score [ADCOMS], 30%; and Clinical Dementia Rating Scale-Sum of Boxes [CDR-SB], 26%) [9]. Dose-dependent changes from baseline were observed across the amyloid PET results and the clinical endpoints.

The objective of this study was to estimate the potential VBP of lecanemab + standard of care (SoC) based on the observed phase II efficacy in Study 201 vs. SoC alone corresponding to the broader range of willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds recommended by ICER in its Value Assessment Framework (from $50,000 to $200,000 per QALY) [10]. An evidence-based disease simulation model [11] was updated with data from Study 201 and published literature to compare lecanemab + SoC vs. SoC alone in different patient populations, both from the US payer and societal perspectives; costs and disutility for caregivers were also considered.

Methods

Model Overview

AD Archimedes condition-event (ACE) is a patient-level simulator that captures complex interactions among key AD pathology components (e.g., underlying biomarkers such as Aβ measures and tau levels) and the clinical presentation of AD, based on various patient-level scales of cognition, behavior, function, and dependence (Fig. 1) [11, 12]. Comprehensive external validations using patient registries, clinical trials, and published literature have shown that AD ACE can correctly predict and provide reasonable transition estimates of AD dementia, institutionalization, and mortality over a long-term horizon [11, 12].

High-level model diagram outlining the key relationships in the AD ACE simulator. *Key baseline patient characteristics: age, sex, race, education, ApoE4 status, baseline biomarkers, baseline scales. †DMT effect is directly applied on amyloid PET SUVr level. ‡Includes ARIA-E. §DMT initiates on confirmed amyloid-positive MCI due to AD or patients with mild AD and discontinues once patients progress to moderate AD. ¶Defined by CDR-SB thresholds: MCI due to AD < 4.5, mild AD ≥ 4.5 to < 9.5, moderate AD ≥ 9.5 to < 16, severe AD ≥ 16. AD Alzheimer’s disease, DMT disease-modifying therapy, ADAS-Cog Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive, ADL activities of daily living, ApoE4 apolipoprotein E4, ARIA-E amyloid-related imaging abnormalities-edema/effusion, CDR-SB Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes, CSF t-tau cerebrospinal fluid total-tau, DAD Disability Assessment Scale for Dementia, DS dependence scale, FDG-PET fluorodeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography, IADL instrumental activities of daily living, MMSE Mini-Mental State Examination, NPI Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire, PET positron emission tomography, SUVr standard uptake value ratio

The model simulated the effects of disease modification and early intervention on disease progression with impacts on clinical and economic outcomes. For early AD, the relationships among changes were quantified using predictive mixed linear equations derived from long-term observational data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) [13]. As patients progress to more severe stages of AD that the ADNI study does not effectively represent, the AD ACE switches to Assessment of Health Economics in Alzheimer’s Disease II (AHEAD) equations for cognition and behavioral scales to make the model more representative and accurate across all stages of AD [14, 15]. In this study, AD ACE triggered a switch between the ADNI and AHEAD equations once a simulated patient progressed into moderate AD and the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score fell below 15. Additionally, the model captured transitions to/between community and institutional care settings as patients progressed to more severe stages of AD.

The model captured the mean and incremental patient life years (LY), QALYs, delay to onset of AD dementia, and different treatment- and AD-related care costs. Direct and indirect care costs for patients and caregivers were reported separately in the community and institutional care settings. The overall QALYs were broken down to patient QALYs, caregiver QALYs lost, and QALYs lost to amyloid-related imaging abnormalities-edema/effusion (ARIA-E) adverse events (AE). An annual discount rate of 3% was applied to all health and economic outcomes in accordance with the recommendations for cost-effectiveness analyses in the USA [16].

An early AD population was selected for the base-case analysis; this aligned with the patient characteristics in both Study 201 and the ongoing phase III CLARITY AD trial (i.e., MCI due to AD and mild AD dementia and confirmed Aβ pathology). A total of 1735 ADNI participant profiles were available and 429 profiles were selected as inputs for the AD ACE simulator; this subgroup was matched on key Study 201 inclusion criteria: ages 50–90 years, Mini-Mental State Examination ≥ 22, and amyloid PET SUVr level ≥ 1.1 [7]. The mean baseline characteristics of the selected profiles aligned closely with the placebo and 10 mg/kg biweekly lecanemab groups of the trial (Table 1). A total of 2000 individual patient profiles were sampled with replacement from the selected subgroup of 429 ADNI patients and simulated separately on the lecanemab + SoC and SoC alone arms to capture AD disease trajectory and treatment effect.

The modeled base case explored the early AD population of MCI due to AD and mild AD dementia and confirmed Aβ pathology. Assessments were conducted for key patient subsets and alternative treatment stopping rules and dosing regimens. Sensitivity and scenario analyses were conducted to explore the impact of different settings and parameter uncertainty on the outcomes.

Scenario analyses examined the impact of early or late treatment on delaying the onset of AD dementia or progression to more severe disease through patient subsets defined on the selected base-case 429 ADNI profiles. Additionally, profiles were grouped by quintile, according to baseline cerebrospinal fluid total-tau (CSF t-tau), to investigate the impact of early-to-late treatment based on neurodegeneration level as measured by CSF t-tau.

AD ACE was also recently used to study the long-term health outcomes of lecanemab in patients with early AD [17]. All the treatment settings and assumptions considered in the AD ACE model for the health outcomes study and this VBP assessment were aligned except the assumed rate of treatment discontinuation in the base-case scenario which resulted in slight difference in reported outcomes common between the two studies. No treatment discontinuation was assumed in the health outcomes study to help assess the true efficacy of treatment with lecanemab and its impact on clinical outcomes in study participants who strictly adhered to the protocol and planned treatment whereas in this study the observed rate of discontinuation in Study 201 was considered.

The BAN2401-G000-201 (Study 201) trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonization and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each site. All patients provided written informed consent. An independent interim monitoring committee was responsible for oversight and conduct of the interim analyses and response-adaptive randomization design to evaluate the safety routinely and review the futility analysis results. This assessment is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Model parameters related to costs, mortality, disease progression equations, risk of transition to institutional care, and health-related quality of life for patients and caregivers were primarily informed by published literature. Other parameters in the model such as the baseline population, treatment effect, and treatment discontinuation were informed by the Study 201 outcomes. Additional details regarding each of these are provided below.

Disease Progression

The natural history of AD progression for patients receiving SoC was modeled using AD ACE based on disease equations developed from longitudinal patient-level ADNI data for early AD [13] and published AHEAD equations for more severe stages of AD [14, 15]. CDR-SB thresholds were used to determine patients’ disease severity at baseline and over time in AD ACE (i.e., MCI due to AD < 4.5, mild AD ≥ 4.5 to < 9.5, moderate AD ≥ 9.5 to < 16, severe AD ≥ 16) [18]. Accordingly, the proportion of patients with MCI due to AD at the start of the simulation in AD ACE (i.e., CDR-SB score < 4.5 corresponding to CDR Global = 0.5) should be compared to the proportion of patients with CDR Global of 0.5 at baseline in Study 201. Disease severity levels assigned by ADNI on the basis of clinical evaluation of patients are also provided in Table 1 and should be compared to the reported proportion of patients with MCI due to AD diagnosis in Study 201. Model inputs such as patient utility, caregiver disutility, care cost, and hazards of mortality and institutional care changed with disease progression.

Mortality was modeled by applying hazard ratios (HR) to age-specific US general population survival [19] to naturally increase the probability of death across all AD severity stages with age. The HR estimates from Andersen et al. [20], a random, population-based cohort study, were used for the base-case settings (Table 1). These HR estimates were reported by AD severity defined by CDR-SB scores in Andersen et al. [20]. The results in Andersen et al. demonstrated that the presence and severity of AD dementia corresponded to reduced survival based on a 14-year study duration. The current modeling analysis assumed that MCI due to AD did not impact mortality risk. The HRs from Wimo et al. [21] were explored in a scenario analysis.

Institutional Care

The incidence-based institutionalization estimates leveraging Consortium to Establish a Registry for AD (CERAD) data were used in the model to inform the probability of transitioning from the community to nursing home (i.e., institutionalized) care by AD severity level (Table 1) [22]. No risk of admission to institutional care was assumed for patients with MCI due to AD as a result of limited published evidence and minimal impact on the outcomes. Alternative prevalence-based institutionalization data from Davis et al. [23] that reflected the proportion of patients institutionalized at each AD severity level was explored in scenario analyses. AD severity reported in both selected studies were defined on the basis of CDR-Global score.

Treatment Effect and Dosing

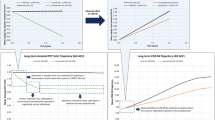

The treatment effect in this study was modeled on the basis of the key assumption that the effect of lecanemab on the clinical outcomes is correlated with amyloid PET level as a surrogate endpoint [24, 25]. In AD ACE the relationships between biomarkers of disease and clinical outcomes are based on correlations mainly observed in the ADNI data. Disease equations are evaluated repeatedly at subsequent time intervals every 6 months to estimate the AD disease trajectory of patients. An anti-amyloid DMT can be potentially modeled in AD ACE by imposing effects on estimated amyloid PET SUVr outcomes of a simulated patient. In this study, a calibration process to only adjust the predicted measures of amyloid PET SUVr at each time interval was used to model the treatment effects of lecanemab over time (Fig. 2). Amyloid PET is a predictor in all AD ACE disease equations; therefore, any calibrated reduction in amyloid PET SUVr at a given time interval impacts the prediction of amyloid PET SUVr and other modeled AD biomarkers and scales such as CDR-SB at later time intervals. Calibration is a process of adjusting the parameters of a model until a chosen sample reaches the known outcome within an acceptable range.

Reported data from the 10 mg/kg biweekly group of Study 201 on change in amyloid PET SUVr from baseline was used as the basis for calibrating mean amyloid reductions required at different time intervals to closely match the observed percentage change in CDR-SB from baseline in Study 201 during the first 18 months of treatment initiation. The data on change in amyloid PET from a model-based simulation study that explored the effect of continued treatment with 10 mg/kg intravenous biweekly dose of lecanemab [26] was then used to calibrate treatment effect beyond the Study 201 time horizon until the mean amyloid level reached the mean amyloid level observed in cognitively normal individuals in the ADNI data set [13]. Additional reduction in amyloid PET level was then calibrated to maintain the cognitively normal mean amyloid level for patients while they remain on lecanemab, an assumption validated by clinical experts. The calibration process only adjusted the estimated PET SUVr values over time and did not impact default AD ACE equations.

A lifetime simulation of 2000 sampled ADNI patients was used during the treatment effect calibration process where treatment discontinuation was not allowed. The resulting trajectories of amyloid PET and CDR-SB for both lecanemab + SoC and SoC arms (Fig. 2) indicated that the change relative to SoC achieved in amyloid PET SUVr and CDR-SB in the AD ACE model mirrored Study 201 results during the trial duration.

In the base-case scenario, patients on treatment were assumed to receive a 10 mg/kg intravenous biweekly dose of lecanemab, which resulted in a 26% change from baseline in CDR-SB. This change was estimated on the basis of the conventional mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM), which cannot generate a confidence interval around ratios (i.e., percentage reduction or percentage change from baseline). Consequently, a ± 15% variation was considered in the sensitivity analyses to explore the uncertainty surrounding lecanemab treatment effect. This was consistent with the reported range of percentage reductions estimated from six different statistical methods in a recent study [27]. The impact of alternative treatment dosing regimens and their potential impact on treatment effect during a maintenance phase were also explored in the scenario analysis. Outcomes reported from the model-based simulation study were used to inform alternative treatment effect scenarios in the model, where long-term maintenance dosing of lecanemab beyond the 18-month trial period was investigated [26]. The model-based simulation data suggested that less frequent dosing may be feasible to prevent re-accumulation of amyloid and maintain treatment effect beyond the trial duration [26]. For each dosing regimen scenario, the mean amyloid reduction was recalibrated in the maintenance time intervals by proportionally adjusting the mean amyloid reductions estimated in the base-case setting.

Treatment Discontinuation

The discontinuation risk in Study 201 was 35.6% (217 subjects) in the lecanemab arm vs. 23.3% (57 subjects) in the placebo group over the 18-month trial period [9]. The risk was higher in the lecanemab 10 mg/kg monthly (92 [36.4%]) and biweekly groups (71 [44.1%]) for reasons considered unrelated to treatment (i.e., at the discretion of regulatory authorities). Approximately one-quarter (24.8%) of participants in the 10 mg/kg biweekly group discontinued treatment because of treatment-related AEs, subject choice, or inadequate therapeutic effect. This translated into a 17.3% annual risk of discontinuation, which was used in the base-case analysis. Alternative annual risk levels of 10% and 20% were explored in the sensitivity analyses. Progression to the moderate AD health state (i.e., CDR-SB ≥ 9.5) also triggered treatment discontinuation in the base case. Treatment stopping rules based on fixed treatment durations of 1.5, 3, and 5 years where patients discontinued treatment were also explored in scenario analyses. Once a patient discontinued treatment because of any of the modeled conditions in this study (i.e., risk, progression, or stopping rule), the mean calibrated amyloid reductions estimated over lifetime were not applied in time intervals beyond the discontinuation time, so the changes in amyloid level at each time interval were estimated solely on the basis of evaluation of the amyloid PET disease equation in AD ACE.

AEs

The incidence rates of serious AEs and treatment-emergent AEs other than ARIA-E (e.g., falls) and infusion reactions were similar in both treatment arms in Study 201 and were consistent with AEs observed in an early AD population. Infusion reactions were mainly mild to moderate (grade 1–2) and typically responded to prophylactic treatment. Sixteen cases of ARIA-E were observed in 161 patients in the 10 mg/kg biweekly group; three were symptomatic cases of headaches, visual disturbances, or confusion [9]. Hence, the model only accounted for the impact of ARIA-E in the first year with a 9.9% occurrence rate, and 18.8% of these cases were symptomatic. ARIA-E events only resulted in short treatment interruptions in Study 201; therefore, no treatment discontinuation was considered in the model as a result of ARIA-E events.

Utilities

Patient utilities were informed by Landeiro et al. [28], a fixed-effect meta-analysis using studies from a systematic literature review. The same utility estimated on the basis of disease severity was used in the community and institutionalized settings (Table 1). The studies identified in the systematic review defined AD severity on the basis of MMSE, CDR-Global, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale, the Global Deterioration Scale, or a combination of two or more of these measures [28]. Values from Neumann et al. [29], which defined AD severity on the basis of the CDR-Global score, were considered in the scenario analysis. An estimated disutility of − 0.14 for headache [30] was also applied to patients experiencing ARIA-E for 12 weeks [9]. Caregiver disutilities were taken from Mesterton et al. [31]; patients were assumed to have one caregiver.

Costs

The study analyzed the direct and indirect community and residential care costs for patients and caregivers. US cost data across the full disease continuum are lacking, so inputs from multiple sources were combined as needed. The results from GERAS-US [32], a prospective, longitudinal cohort study adapted from GERAS I [33], were used to inform the community-based care costs for patients with MCI and mild AD. GERAS-US assessed the cross-sectional total societal costs for patients with MCI and mild AD, including direct medical and non-medical costs for healthcare resource use and indirect costs for caregiving. Both GERAS I and GERAS-US used the MMSE scale to define AD severity [32, 33]. GERAS I was conducted in multiple European countries and reported on community-based costs for patients with mild, moderate, and severe AD dementia; the study found that costs increased with disease severity. The mean monthly costs for patients with moderate and severe AD dementia were not reported in GERAS-US. Therefore, the mean relative ratio between estimated costs for mild AD vs. moderate and severe AD from GERAS I for three European countries was computed and applied to the community-based care costs for mild AD from GERAS-US to approximate mean US monthly costs. The computed mean relative ratios for mild-to-moderate AD (1.3) and mild-to-severe AD (1.9) were well aligned with the findings from Leon et al. [34] and Small et al. [35], on relative change in average cost of care by disease stage. Additionally, these relative ratios calculated on the basis of costs reported in GERAS I are in line with the average ratios (across all three age groups) used by the Alzheimer’s Association [36] for mild-to-moderate AD (1.3) and mild-to-severe AD (2.0).

The direct non-medical costs in the residential care setting were informed by Genworth’s Cost of Care Survey tool [37]. The 2021 monthly median cost for a private/semi-private room in a US residential care facility was $8477; the model did not adjust this cost by disease stage since it is usually a flat rate. Other residential care costs were assumed to be the same as community-based care costs for both patients and caregivers except for indirect non-medical costs for caregiving where only 44% of the informal care cost in the community-based setting was applied [38].

Patients receiving lecanemab accrued monitoring costs which were assumed to be the cost of five magnetic resonance imaging scans in the first year. The unit costs were collected from Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Physician Fee Schedule [39]. Symptomatic treatment costs were accounted for in GERAS estimates and thus not included in the analysis. Medical resource use (MRU) associated with ARIA-E stratified by severity and type (symptomatic/asymptomatic) was informed by the Study 201 protocol. MRU costs were collected from the CMS database [40] and IBM® RED BOOK® [41]. The costs of diagnostics and screening (e.g., CSF and PET scans) were not considered in the base case because of uncertainties around requirements and potential variations in reimbursement policies; instead, these costs were explored in scenario analyses. All costs were inflated to 2021 US dollars using the US Bureau of Economic Analysis price index for personal consumer expenditures for healthcare [42]. The breakdown of all cost categories is provided in Table 2.

Results

Base-case Analysis

Patients treated with lecanemab + SoC experienced slower disease progression than those treated with SoC, translating into 0.62 incremental discounted LYs (7.0 years vs. 6.38 years, respectively). The mean time on lecanemab was 3.77 years and the treatment was associated with 0.61 total incremental QALYs from the US payer perspective, and 0.64 incremental QALYs from the societal perspective once caregiver disutility was considered. The total incremental costs associated with lecanemab (excluding drug acquisition costs) were − $8707 and − $11,214 per person from the US payer and societal perspectives, respectively. The mean costs of community-based care increased by $4285 while residential care costs decreased by $14,068 from the payer perspective—a total incremental care cost of − $9784 per person ($208,694 for lecanemab + SoC vs. $218,477 for SoC). Lecanemab treatment also resulted in additional monitoring and ARIA-E management costs ($1024 and $53, respectively). A similar trend was observed for the societal perspective (Table 3). For a WTP threshold range of $50,000 to $200,000 per QALY gained, the annual VBP of lecanemab was estimated between $9249 and $35,605 and between $10,400 and $38,053 for the US payer and societal perspectives, respectively.

Scenario Analyses

Scenario analyses explored the impacts of alternative population subsets, model settings, input sources, and assumptions. Incremental outcomes including LYs, QALYs, total costs, and VBP based on $200,000 per QALY gained WTP threshold are presented in Table 4. For patients with MCI due to AD, the model estimated additional incremental QALYs and lower incremental costs over a lifetime vs. the base case, resulting in 5% (payer) and 6% (societal) increases in VBP. In the mild AD dementia subset, the overall gain in QALYs decreased by 0.29 vs. the base-case scenario where most patients did not have AD dementia at baseline; the model estimated a 39% (payer) and 44% (societal) reduction in VBP. Initiating lecanemab in patients with a median baseline age of 65 years resulted in additional lifetime QALY gains and cost-savings (i.e., payer, 24%; societal, 26% increase in VBP). The predicted benefit from lecanemab treatment was further observed when including MCI due to patients with AD in a younger cohort with median baseline age of 65 years (33% [payer] and 37% [societal] increase in VBP). When patients were further divided into quintiles defined by baseline CSF t-tau level, lecanemab produced better outcomes and a higher VBP in patients earlier in their tau tangle pathology. When subsets were defined on the basis of CSF t-tau quintiles, the VBP changed from 19% to − 27% and 22% to − 29% vs. the base case for the payer and societal perspectives, respectively.

Shorter time horizons of 5 and 10 years resulted in smaller predicted incremental QALYs and lower VBPs compared with the lifetime base case from both perspectives. Using HRs from Wimo et al. [21] to inform the parameters of inputs for mortality did not significantly impact the incremental QALYs but resulted in 9% (payer) and 14% (societal) increases in VBP vs. the base case. Lower HRs for mortality in Wimo et al. resulted in longer survival, especially in later states where costs and thus the potential for cost offsets were higher. The incremental QALYs declined by 0.05 vs. the base case when Neumann et al. [29] was used to inform patient utilities in different AD severity levels. Changing the risk of transitioning to institutional care and including screening costs slightly impacted model results.

The effect of treatment discontinuation and duration was further explored in different scenarios. In all scenarios, we assumed that the treatment would confer no residual benefit beyond discontinuation once treatment is interrupted or discontinued, except for one scenario in which the achieved amyloid reduction over a treatment duration of 1.5 years was maintained over a lifetime after discontinuation. The predicted VBP and gain in QALYs were higher the longer patients stayed on treatment. Different maintenance phase dosing schedules after 1.5 years were explored in the scenario analyses where individuals who previously received lecanemab for 1.5 years would switch from the biweekly dosing schedule to once every 4–12 weeks. When the treatment effect was kept the same as the base case, the predicted increase in VBP ranged from 45% to 103% (payer) and 44% to 103% (societal) with the biweekly dosing for the induction phase (initial 1.5 years) followed by once every 4–12 weeks for the maintenance phase. When similar dosing regimen scenarios were explored but the treatment effect on amyloid reduction was adjusted in the maintenance phase, the predicted increase in VBP slightly declined, ranging from 35% to 70% (payer) and 34% to 68% (societal).

Sensitivity Analyses

A series of one-way sensitivity analyses were conducted to demonstrate how variation in key parameters affects the overall findings of this study, which are presented in a tornado diagram (Fig. 3) from the societal perspective at a $200,000 per QALY gained WTP threshold. Adjusting the discount rate to 0.0% and 5.0% had the most impact on the potential VBP of lecanemab where it changed by 18.8% and − 10.5%, respectively, vs. the base case. The predicted VBP changed by − 12.5% and 13.0% when applying an annual discontinuation risk of 10% and 25%, respectively. Varying the treatment effect on the percentage reduction in CDR-SB vs. SoC to 30% and 22% (i.e., ± 15% of base-case value of 26%) had a positive correlation and changed VBP by 7% and − 8.4% respectively. The higher the patient utilities for MCI due to AD were, the higher the predicted VBP was. Care costs for moderate and severe AD were also positively associated with the model’s predicted VBP whereas care costs for mild AD and MCI due to AD were negatively associated with VBP. Lower mortality HRs for severe AD (6.6 vs. 9.52 in the base case) and utilities for patients with moderate and severe AD resulted in higher estimated VBP for lecanemab. Varying the remaining parameters led to VBP differences of less than 3% compared to the base case.

Discussion

This early modeling analysis used the AD ACE disease simulator to evaluate the clinical and economic outcomes of lecanemab + SoC vs. SoC only and to predict the potential VBP to meet various WTP thresholds in the USA. AD ACE’s flexible framework allowed assessment of the impact of different patient subsets and major sources of uncertainty in this study. Amyloid-positive patients with MCI due to AD or mild AD dementia had an additional 0.61 gain in QALYs (societal, 0.64) and a $8707 decrease in total non-treatment costs (societal, $11,214) when treated with lecanemab + SoC in the base case vs. SoC alone. For people treated with lecanemab, the total institutional care costs decreased by $11,097 (societal, $18,205) but the total community care costs increased by $4285 (societal, $5915) as treated patients spent more time in the community care over their lifetime. At WTP threshold of $200,000 per QALY gained, the estimated annual VBP for lecanemab was $35,605 and $38,053 from the payer and societal perspectives, respectively.

In the scenario analyses, lecanemab had a greater impact on total non-treatment costs and QALYs when initiated at earlier ages in patients with MCI due to AD, and in patients earlier in their tau pathology (lower quintiles). The estimated gain in QALYs was 0.67–0.88 in the MCI due to AD subset vs. 0.32 in the mild AD dementia subset; this was consistent with findings that DMTs may be more effective when initiated at pre-symptomatic stages of dementia [43].

Data from Study 201 suggested that when lecanemab treatment was discontinued at the end of the 18-month trial duration, changes in the plasma biomarkers and amyloid PET SUVr gradually began to reverse, suggesting that stopping therapy prematurely may potentially allow re-accumulation of pathology. Less frequent maintenance dosing to prevent re-accumulation and maintain treatment effect may be possible on the basis of data and simulation modeling [26]. Scenario analyses on treatment stopping indicated that longer time on treatment or maintenance of a residual effect after discontinuation resulted in higher QALYs gained and increased cost savings. Lowering the dosing regimen in the maintenance phase increased the VBP but the estimated price slightly decreased when treatment effect on amyloid reduction was adjusted as a result of dose adjustment.

A key strength of this modeling analysis was that actual individual patient characteristics were used, rather than mean cohort characteristics, to better capture heterogeneity. Disease progression in AD ACE was modeled using equations that explicitly tracked the change in amyloid level and CDR-SB, the secondary endpoints in Study 201. This differs from Markov models [44, 45] in which the treatment effect is typically expressed as a reduction in transition probabilities between discrete health states of different severity and is assumed to last through treatment duration with often a constant progression rate. The treatment effect was also modeled by calibrating the reduction in amyloid level to achieve the effects observed during the trial (Fig. 2). The calibration process requires estimates of amyloid level at baseline and reductions over time with adequate trial duration for the estimation of model outputs. Measurement errors in amyloid PET SUVr brain imaging and trial durations that are too short may result in calibration errors and estimation bias of important measures such as the treatment effects, costs, or QALYs. Therefore, accurate estimates of PET SUVr and adequate trial duration to capture long-term treatment effects are required to model and evaluate the potential impacts of interventions to avoid an under- or overestimation of, for example, the treatment effect.

Some limitations of the model should be considered. There was an implicit assumption in this model-based study that the effects of lecanemab treatment on key clinical outcomes are mediated, or predicted, by amyloid PET level as a surrogate endpoint. If the assumption of conditional independence is not warranted, it may lead to biased estimates of mean costs and QALYs, and the underestimation of uncertainty [46]. Failure to account for uncertainty and reliance on inappropriate surrogate endpoints may undermine the value of future research. However, the lecanemab phase III CLARITY AD trial is being conducted and its outcomes, when completed, can serve as the confirmatory study to verify the clinical benefit of lecanemab treatment. The efficacy data was based on the 18-month Study 201 and expert opinion was used to model the long-term effect of lecanemab; however, data from the confirmatory phase III study in early AD (CLARITY AD) will be available soon that may refine the findings. Although the model used the most relevant studies to inform mortality risk, risk of institutional care, utility, and costs, there was uncertainty around these parameters. The model only explored the indirect effect of treatment on cognition through CDR-SB and did not assess other severity domains (e.g., behavior, function, or dependence) or composite measures such as ADCOMS, which was Study 201’s primary endpoint. The model also projected severity using one disease severity measure (CDR-SB) and modeled risk of institutional care and patient utility through simple estimates based on disease severity.

Longer-term clinical trial follow-up and longitudinal real-world data are needed to better validate the key assumptions in this model. Market authorization will create a valuable opportunity to collect real-world lecanemab data and additional supporting evidence. This analysis demonstrated that lecanemab has the potential to delay the onset of AD which can lead to an increase in disease-free years and sizable cost-savings for care, providing significant benefits to patients, their caregivers, and society.

Conclusions

This early economic evaluation suggested that lecanemab + SoC compared with SoC alone can potentially lead to higher LYs and QALYs and reduced costs of care for patients and caregivers in early AD. The results on VBP and estimated value of delay in AD onset can provide a foundation for healthcare decision-makers to understand the potential clinical, economic, and societal value of lecanemab.

References

Kochanek K, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief, No. 395. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020.

Alzheimer's Association. 2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures 2020. https://www.alz.org/aaic/downloads2020/2020_Facts_and_Figures_Fact_Sheet.pdf.

Cummings J, Lee G, Zhong K, Fonseca J, Taghva K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2021. Alzheimers Dement (NY). 2021;7(1): e12179.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA grants accelerated approval for Alzheimer's drug 2021. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-alzheimers-drug.

Whittington MD, Campbell JD, Rind D, Fluetsch N, Lin GA, Pearson SD. Cost-effectiveness and value-based pricing of aducanumab for patients with early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2022;98(9): e968.

Haeberlein S, Hehn C, Tian Y, et al. Emerge and engage topline results: phase 3 studies of aducanumab in early Alzheimer’s disease: developments in clinical trials and cognitive assessment. Alzheimers Dement. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.047259.

Eisai Inc. A study to evaluate safety, tolerability, and efficacy of lecanemab in subjects with early Alzheimer's disease: Clinicaltrials.gov; 2013 (updated 2021).

Lynch SY, Irizarry MC, Dhadda S, et al. Baseline characteristics for CLARITY AD: a phase 3 placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group, 18-month study evaluating lecanemab (ban2401) in early Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(S9): e054331.

Swanson CJ, Zhang Y, Dhadda S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, phase 2b proof-of-concept clinical trial in early Alzheimer’s disease with lecanemab, an anti-Abeta protofibril antibody. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2021;13(1):80.

Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). 2020–2023 Value Assessment Framework 2020. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_2020_2023_VAF_102220.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Kansal AR, Tafazzoli A, Ishak KJ, Krotneva S. Alzheimer’s disease Archimedes condition-event simulator: development and validation. Alzheimers Dement (NY). 2018;4:76–88.

Tafazzoli A, Weng J, Sutton K, et al. Validating simulated cognition trajectories based on ADNI against trajectories from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center (NACC) dataset. In: 11th edition of Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease (CTAD); Barcelona, Spain. 2018.

Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative [homepage] 2017. http://adni.loni.usc.edu/. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Getsios D, Blume S, Ishak KJ, Maclaine GD. Cost effectiveness of donepezil in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a UK evaluation using discrete-event simulation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(5):411–27.

Guo S, Getsios D, Revankar N, et al. Evaluating disease-modifying agents: a simulation framework for Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(11):1129–39.

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for conduct, methodological practices, and reporting of cost-effectiveness analyses: second panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1093–103.

Tahami Monfared AA, Tafazzoli A, Ye W, Chavan A, Zhang Q. Long-term health outcomes of lecanemab in patients with early Alzheimer's disease using simulation modeling. Neurol Ther. 2022;11:863–880.

O’Bryant SE, Waring SC, Cullum CM, et al. Staging dementia using clinical dementia rating scale sum of boxes scores: a Texas Alzheimer’s research consortium study. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(8):1091–5.

Arias E. United States life tables, 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2019;68(7):1–66.

Andersen K, Lolk A, Martinussen T, Kragh-Sorensen P. Very mild to severe dementia and mortality: a 14-year follow-up. The Odense study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;29(1):61–7.

Wimo A, Handels R, Winblad B, et al. Quantifying and describing the natural history and costs of Alzheimer’s disease and effects of hypothetical interventions. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(3):891–902.

Neumann PJ, Hermann RC, Kuntz KM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of donepezil in the treatment of mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1999;52(6):1138–45.

Davis M, Thomas OC, Johnson S, et al. Estimating Alzheimer’s disease progression rates from normal cognition through mild cognitive impairment and stages of dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2018;15(8):777–88.

Avgerinos KI, Ferrucci L, Kapogiannis D. Effects of monoclonal antibodies against amyloid-beta on clinical and biomarker outcomes and adverse event risks: a systematic review and meta-analysis of phase III RCTs in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;68: 101339.

Fletcher E, Filshtein TJ, Harvey D, Renaud A, Mungas D, DeCarli C. Staging of amyloid beta, t-tau, regional atrophy rates, and cognitive change in a nondemented cohort: results of serial mediation analyses. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2018;10:382–93.

Bateman R, McDade E. Phase 2 lecanemab early Alzheimer’s disease study biomarker results and correlations with clinical outcomes. AD/PD 2022, International Conference on Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases and related neurological disorders; March 15–20, 2022; Barcelona, Spain. 2022.

Dhadda S, Kanekiyo M, Li D, Swanson CJ, et al. Consistency of efficacy assessments across various statistical methods from the lecanemab phase 2 proof-of-concept study, BAN2401-G000–201, in subjects with early Alzheimer’s disease [Oral Presentation]. Clinical Trials in Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD), November 9–12, 2021; Boston, MA, 2021.

Landeiro F, Mughal S, Walsh K, et al. Health-related quality of life in people with predementia Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment or dementia measured with preference-based instruments: a systematic literature review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):154.

Neumann PJ, Kuntz KM, Leon J, et al. Health utilities in Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional study of patients and caregivers. Med Care. 1999;37(1):27–32.

Xu R, Insinga RP, Golden W, Hu XH. EuroQol (EQ-5D) health utility scores for patients with migraine. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(4):601–8.

Mesterton J, Wimo A, By A, Langworth S, Winblad B, Jonsson L. Cross sectional observational study on the societal costs of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7(4):358–67.

Robinson RL, Rentz DM, Andrews JS, et al. Costs of early stage Alzheimer’s disease in the US: cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort study (GERAS-US)1. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(2):437–50.

Wimo A, Reed CC, Dodel R, et al. The GERAS Study: a prospective observational study of costs and resource use in community dwellers with Alzheimer’s disease in three European countries–study design and baseline findings. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;36(2):385–99.

Leon J, Cheng CK, Neumann PJ. Alzheimer’s disease care: costs and potential savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 1998;17(6):206–16.

Small GW, McDonnell DD, Brooks RL, Papadopoulos G. The impact of symptom severity on the cost of Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(2):321–7.

Alzheimer's Association. Alzheimer’s association trajectory report 2015. Appendix A 2015. https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/trajectory-report-appendix-a.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Genworth. Cost of care survey 2022. https://www.genworth.com/aging-and-you/finances/cost-of-care.html. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

DiBenedetti DB, Slota C, Wronski SL, et al. Assessing what matters most to patients with or at risk for Alzheimer’s and care partners: a qualitative study evaluating symptoms, impacts, and outcomes. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):90.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. January 2022 Update of the Ambulatory Surgical Center (ASC) Payment System 2022. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mm12553-january-2022-update-ambulatory-surgical-center-asc-payment-system.pdf. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. CY 2022 National Payment Amount by HCPCS Code 2022. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

IBM. IBM Micromedex® RED BOOK®. https://www.ibm.com/products/micromedex-red-book. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed 14 Apr 2022.

Di Carlo M, Giacomazza D, San Biagio PL. Alzheimer’s disease: biological aspects, therapeutic perspectives and diagnostic tools. J Phys Condens Matter. 2012;24(24): 244102.

Herring WL, Gould IG, Fillit H, et al. Predicted lifetime health outcomes for aducanumab in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Ther. 2021;10(2):919–40.

Synnott PG, Whittington MD, Lin GA, Rind DM, Pearson SD. The effectiveness and value of aducanumab for Alzheimer’s disease. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(11):1613–7.

Hawkins N, Richardson G, Sutton AJ, et al. Surrogates, meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness modelling: a combined analytic approach. Health Econ. 2012;21(6):742–56.

Rabinovici GD, Gatsonis C, Apgar C, et al. Association of amyloid positron emission tomography with subsequent change in clinical management among medicare beneficiaries with mild cognitive impairment or dementia. JAMA. 2019;321(13):1286–94.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Eisai Inc.

Editorial and Other Assistance

The authors would like to acknowledge Evidera’s editor, Colleen Dumont, for proofreading and editorial services funded by Eisai Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Amir Abbas Tahami Monfared and Ali Tafazzoli conceptualized the study and were responsible for its overall direction and planning, with input from Quanwu Zhang. Ali Tafazzoli, Weicheng Ye, and Ameya Chavan developed the model and performed the analyses.

Disclosures

Weicheng Ye, and Ameya Chavan are current employees of Evidera, a healthcare research firm that provides consulting and other research services to pharmaceutical, device, government, and non-government organizations. Ali Tafazzoli is a former employee of Evidera. Evidera received funding from Eisai Inc. to conduct the study and develop this manuscript. Amir Abbas Tahami Monfared and Quanwu Zhang are employees of Eisai Inc.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The BAN2401-G000-201 (Study 201) trial was conducted in accordance with Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council for Harmonization and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each center. All patients provided written informed consent. An independent interim monitoring committee was responsible for oversight and conduct of the interim analyses and response adaptive randomization design to evaluate the safety routinely and reviewing futility analysis results. This assessment is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data used for this study are provided in the manuscript. Additional details are available from the corresponding author on request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tahami Monfared, A.A., Tafazzoli, A., Chavan, A. et al. The Potential Economic Value of Lecanemab in Patients with Early Alzheimer’s Disease Using Simulation Modeling. Neurol Ther 11, 1285–1307 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00373-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00373-5