Abstract

Introduction

The Mediterranean Dietary Approaches to the Stop Hypertension (DASH) Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet has been shown to have beneficial neuroprotective effects. The purpose of this research was to evaluate the link between the MIND diet adherence and multiple sclerosis (MS), a degenerative neurological illness.

Methods

In a hospital-based case–control setting, 77 patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) and 148 healthy individuals were recruited. A validated 168-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire was used to assess participants’ dietary intakes and the MIND diet score. A logistic regression model was used to evaluate the association between MIND diet adherence and MS.

Results

There was significant difference between RRMS and control groups in the median (Q1-Q3) of age (years, P value < 0.001), body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2, P value < 0.001), and total intake of calories (kcal, P value = 0.032), carbohydrates (g, P value = 0.003), animal-based protein (g, P value = 0.009), and fiber (g, P value = 0.001). Adherence to the MIND diet was associated with a reduced odds of MS [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.10, 95 percent confidence interval (95% CI) = 0.01–0.88, P for trend = 0.001]. MS odds was significantly lower in the last tertile of green leafy vegetables (aOR = 0.02, 95% CI = 0.00–0.21, P value < 0.001), other vegetables (aOR = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.04–0.73, P value = 0.001), butter and stick margarine (aOR = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.06–0.65, P value = 0.008), and beans (aOR = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.01–0.28, P value < 0.001) consumption. While it was significantly higher in the last tertile of cheese (aOR = 4.45, 95% CI = 1.70–11.6, P value = 0.003), poultry (aOR = 3.95, 95% CI = 1.01–15.5, P value = 0.039), pastries and sweets (aOR = 13.9, 95% CI = 3.04–64.18, P value < 0.001), and fried/fast foods (aOR = 32.8, 95% CI = 5.39–199.3, P value < 0.001).

Conclusion

The MIND diet and its components, including green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, and beans, seem to decrease the odds of MS; besides butter and stick margarine, the MIND diet's unhealthy components seem to have the same protective effects, while pastries and sweets, cheese, poultry, and fried/fast foods have an inverse effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

An estimated 50–300 people per 100,000 are diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS), an autoimmune degenerative and inflammatory neurological condition without any known cure. |

Studies have shown a link between specific dietary patterns like the Mediterranean diet and reduced risk of multiple sclerosis. |

The newly introduced Mediterranean Dietary Approaches to the Stop Hypertension (DASH) Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet is a combination of Mediterranean and DASH dietary patterns. This study aimed to investigate the association between the MIND diet and MS. |

What was learned from the study? |

The odds of MS are negatively associated with the MIND diet score and its components, including green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, and beans. |

It was learned from the study that encouraging individuals to follow a dietary pattern high in plant-based foods and low in animal-based/high in saturated fat foods, like the MIND diet, may be helpful in preventing multiple sclerosis. |

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune, degenerative, inflammatory neurological disorder of the central nervous system, resulting in myelin and axon destruction [1, 2]. MS is expected to affect about 2.3 million individuals globally, with a prevalence of 50–300 per 100,000 individuals [2]. Among the Middle East countries, the prevalence of MS in the Iranian population is high [3]. A recent meta-analysis in Iran reported the pooled prevalence of MS to be 100 in 100,000 [4]. MS patients usually appear between the ages of 20 to 40 years, with women outnumbering males at a 2:1 ratio [5]. MS is categorized into four subtypes: relapsing–remitting (RRMS), primary-progressive, secondary-progressive, and clinically isolated syndrome. Only some patients with the clinically isolated syndrome will develop into MS [6]. In most patients, MS initiates with a relapsing–remitting phase, and, subsequently, a secondary progressive phase starts between 5 and 35 years after that [5, 7]. The cause is not yet apparent, but genetic, environmental, and behavioral aspects are thought to be associated. Albeit MS does not have a definite treatment, certain disease-adaptive medications and dietary and lifestyle adjustments have been shown to be effective [8].

The Mediterranean diet is among the four dominant dietary patterns reported in a sample of the Iranian population [9]. The Mediterranean diet is a well-studied dietary pattern that has been linked to a decreased MS risk and improved MS course and disability in previous studies [10,11,12,13,14]. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) is a less well-studied dietary strategy concerning MS [15]. Considering that particular dietary ingredients promoting brain function have not been incorporated in DASH and Mediterranean diets, Morris et al. have recently proposed a combination of these two dietary patterns specifically demonstrating neuroprotective effects [16]. This new nutritional pattern called the Mediterranean–DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet encourages natural plant-based meals and limits animal-based/high in saturated fat foods. It especially emphasizes berries and green leafy vegetables [16], rich in anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and neuroprotective components [17]. Better adherence to the MIND diet has been linked to a decreased risk of cognitive deterioration [18]. However, to our knowledge, the association between the MIND diet and MS is not yet apparent. Hence, this study hypothesized that MIND diet adherence is associated with a reduced odds of MS.

Methods

Ethical Considerations

The research protocol of the present study was confirmed by the Institutional Review Board of National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) (Research number = 962667). Also, the research ethics committee of NIMAD and the research ethics boards of the Sina MS research center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, authorized the study (Ethics code: IR.NIMAD.REC.1396.320). The Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its subsequent revisions were followed in the conduct of the research. All individuals have given written permission to participate in the study.

Study Participants

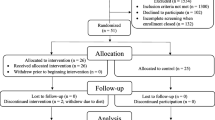

This research was a hospital-based case–control study conducted in Tehran, Iran, between January 2018 and January 2021. A sample of 80 newly-diagnosed participants with RRMS was chosen from the patients referred to a referral University hospital MS clinic using the convenience-sampling approach. RRMS was diagnosed by a neurologist and MS specialist according to physical examination, patient history, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using revised McDonald’s diagnostic criteria [19]. On overage, the patients were included in the current study with 1 week to maximum 1 month after definite diagnosis of MS. The most common drugs received by MS patients were Rituximab, followed by Glatiramer acetate, Interferon beta-1a, Interferon beta-1b, Dimethyl fumarate, while Fingolimod, Teriflunomide, Natalizumab, Ocrelizumab, and Azathioprine were also reported in smaller percentages. Furthermore, a set of 150 hospital-based healthy controls was selected from those referred to the emergency department. Patients with confirmed RRMS diagnosis in the past 12 months, age 18–50 years, and expanded disability status less than 5 were included. Exclusion criteria included adhering to a particular diet in the preceding year and taking dietary supplements, pregnancy and lactation, other types of MS, having had corticosteroid injection (pulse therapy) or RRMS relapse throughout the past month prior to participating in the research, having neurological diseases other than RRMS, and suffering from chronic illness or metabolic disorders that affected their dietary intake (e.g., diabetes and chronic kidney disease). Participants were eliminated from the research if they left more than 70 items blank on the food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). The research protocol of the present study was confirmed by the Institutional Review Board of NIMAD (Research number = 962667). Also, the research ethics committee of NIMAD authorized the study (Ethics code: IR.NIMAD.REC.1396.320). Additionally, all subjects provided written informed permission.

Demographic and Anthropometric Data

A certified nutritionist interviewed each participant face-to-face to collect demographic and anthropometric information. Age, adherence to a specific diet, and drug use history were all considered. A Seca digital body weight scale was used to measure weight with an accuracy of 100 g while standing in light clothing. Height was measured with a tape measure while standing without shoes with a precision of 1 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using weight and height measurements by dividing the weight in kilograms by the height in square meters.

Dietary Assessments

In a face-to-face interview with participants, a certified nutritionist gathered the participants' typical diet over the previous year using a Willet format semi-quantitative FFQ with 168 food items, for which its validity and reliability have been approved for the Iranian population [20,21,22,23]. Individuals reported the frequency of each food item’s intake daily, weekly, monthly, or yearly. Then, using the household scale guide, the stated weight of each food item was converted to grams [24], and the United States Department of Agriculture food composition data were used to estimate each participant's macronutrient intake. The overall amount of energy consumed by each person was calculated by determining the energy content of each food item [25].

MIND Diet Score

The MIND diet score was created using 15 dietary parameters, 10 of which were referred to as brain-healthy food categories (green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, nuts, berries, beans, whole grains, fish, poultry, olive oil, and wine), with the other 5 being referred to as the brain unhealthy food category (red meats, butter and stick margarine, cheese, pastries and sweets, and fried/fast foods) [17]. Wine consumption was not included in the present study's score computation due to a lack of data in our dataset. The remaining 14 food categories were included in the MIND structure. The recommended portions from the original MIND diet rating were used. For example, persons who consumed 6 servings/week and more of green leafy vegetables were assigned a score of 1, those who consumed > 2–6 servings/week were assigned a score of 0.5, and those who consumed 2 and less than 2 servings/week were assigned a score of 0. More details are given in Table 1. The total MIND diet score was then computed by adding the scores for all the dietary factors [17]. As a result, each participant receives a score ranging from 0 to 14.

Statistical Analysis

Considering case:control 2:1, the study power of 80%, type I error of 0.05, and desired confidence interval (CI) of 0.95, the minimum required sample size was estimated to be 68 MS patients and 136 sex-matched healthy individuals. The data in this study were analyzed using the (SPSS) software (v.21; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to analyze the data's normal distribution. To compare normally distributed data across cases and control groups, an independent two-sample t test was used. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze data that were not normally distributed. A Chi-square test was used to assess qualitative confounding variables between the cases and the controls. According to the study controls intakes, all variables were divided into tertiles to investigate the relationship between MS and the MIND diet. Logistic regression models were used to generate the odds ratio (OR) with a 95% CI for each tertile, with the first tertile serving as the reference group. Age, gender, smoking, and energy intake were included in the basic binary logistic regression models. BMI (kg/m2), carbohydrate consumption (g/day), animal-based protein intake (g/day), and fiber intake (g/day) were all included in binary logistic regression models to account for potential confounding factors. To be considered statistically significant, the P value had to be less than 0.05.

Results

After removing ineligible individuals, the research comprised 77 cases and 148 controls. The median (Q1–Q3) of age in the control individuals was significantly greater than in the case group [35.5 (29.0–42.8) and 31.0 (28.5–37.0) years, respectively; P value < 0.001]. There was also a significant difference between the case and control groups in BMI (kg/m2, P value < 0.001), total calories (kcal, P value = 0.032), total carbohydrates (g, P value = 0.003), total animal-based protein (g, P value = 0.009), and total fiber consumption (g, P value = 0.001) (Table 2).

In both the basic and adjusted models, the higher MIND diet score was shown to be statistically significantly associated with a reduced odds of MS (Table 3). In the basic model, those in the top tertile of MIND diet scores had a 95% reduced risk of developing MS than those in the lowest tertile (OR = 0.05, 95% CI 0.01–0.36, P for trend < 0.001). In the latter regression model adjusted additionally for BMI (kg/m2), and carbohydrate (g/day), animal-based protein (g/day), and fiber intake (g/day), compared to those in the first tertile of MIND diet scores, those in the top tertile had 90% lower risk of developing MS [adjusted OR (aOR) = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.01–0.88, P for trend = 0.001]. In both basic and adjusted models, MS odds was lower in the last tertile of green leafy vegetables (aOR = 0.02, 95% CI = 0.00–0.21, P for trend < 0.001), other vegetables (aOR = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.04–0.73, P for trend = 0.001), and beans (aOR = 0.05, 95% CI = 0.01–0.28, P for trend < 0.001) consumption. In the adjusted model, MS odds was lower in last tertile of the butter and stick margarine (aOR = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.06–0.65, P for trend = 0.008). On the other hand, odds of MS was much greater in the last tertile of cheese (aOR = 4.45, 95% CI = 1.70–11.6, P for trend = 0.003), poultry (aOR = 3.95, 95% CI = 1.01–15.5, P for trend = 0.039), pastries and sweets (aOR = 13.9, 95% CI = 3.04–64.18, P for trend < 0.001) and fried/fast foods (aOR = 32.8, 95% CI = 5.39–199.3, P for trend < 0.001) consumption. Although the odds of MS was significantly lower in the third tertile of berries consumption (OR = 0.43, 95% CI = 0.20–0.90, P for trend = 0.024), this significant reduction was not observed after adjusting for confounders (Table 3) The association between MIND diet score and MS odds is also modeled as continuous variables (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

Studying the MIND diet score in this retrospective research shows that higher adherence to the overall MIND dietary pattern may protect against MS. To put it another way, individuals in the third tertile of MIND scores had an estimated 90% lower odds of developing MS, whereas individuals in the middle tertile had an estimated 84% lower odds than those in the first tertile. The evaluated outcomes were unaffected by other dietary factors and BMI.

According to these findings, even a moderate level of MIND diet adherence may significantly impact the prevention of MS. Our findings were consistent with the only research on the MIND diet impacts on MS, which was conducted on 180 newly diagnosed MS patients from the RADIEMS cohort. The thalamic volumes of patients in the last quartile of MIND diet scores were greater than for patients in the first quartile [26].

As previously indicated, the MIND diet combines the Mediterranean and DASH diets and focuses on brain health. The results of the studies on the Mediterranean diet and MS were controversial. The Alternate Mediterranean Diet index was used to assess the dietary patterns of 480 MS patients in the Nurses Health Studies. After accounting for factors such as age, BMI, smoking status, and vitamin D consumption, the researchers found no link between MS risk and Mediterranean Diet adherence [15]. On the other hand, in a study on newly diagnosed MS patients in Croatia (n = 219 over the whole country), in the continental area with low adherence to the Mediterranean Diet, the mean annual incidence of MS was nearly two times greater compared to a coastal area with high adherence to the Mediterranean Diet [11]. According to two Iranian case–control studies, those who eat a diet rich in fresh fruits and vegetables typical of the Mediterranean diet were significantly less likely to develop MS [27, 28]. Observed differences may be attributed to differences in concordance to the Mediterranean diet. Only the greatest Mediterranean diet concordance was linked to disease protection in Alzheimer's disease [16]. Interestingly, according to the findings of the present study, even modest MIND diet adherence may be helpful in preventing MS.

The present results additionally demonstrated that greater vegetable consumption could decrease MS risk. The predicted effect was a 96% and 98% reduction in the odds of MS for persons who consume 57–100 g/day and > 100 g/day green leafy vegetables, respectively. Also, moderate (165–280 g/day) and high (> 280 g/day) intake of other vegetables reduced the odds of MS by 73 and 83%, respectively. These results are in line with those of the previous studies [29,30,31]. Two extensive cohort studies on MS patients reported significantly better physical and mental health with greater fruit and vegetable intake. Both studies used the Diet Habits Questionnaire (DHQ) to assess dietary intakes. The DHQ was first designed for the cardiac rehabilitation population and has since been modified for people with MS. According to the DHQ, patients were grouped into three fruit and vegetable categories: poor (score 1 < 3.5), moderate (score 3.5 < 4.5), and healthy (score 4.5–5) based on their answers to 5 questions [30]. The Australian MS Longitudinal Study results showed an indirect association between physical and mental health and fruit and vegetable consumption, with the strongest associations observed for high intake (score 4.5–5) [31]. According to the results of the HOLISM study, those in the healthy and moderate fruit and vegetable groups had considerably reduced odds of having a greater disability level and a 12-month relapse. The results were similar for moderate and high fruit and vegetable consumption [30]. The DHQ does not define daily fruit and vegetable servings, and does not differentiate between the type of fruit and vegetables [32]. However, the MIND diet has a separate score for green leafy vegetables and recommends the number of servings. The highest score of vegetable consumption is achieved by ≥ 7 servings/week of green leafy vegetables and ≥ 1 serving/day of other vegetables. Moderate intake of vegetables is defined by 2–6 servings/week green leafy and 5–7 servings/week other vegetables [17]. Likewise, in a cross-sectional study on 113 women with MS and 113 healthy controls, there was a significant association between vegetable consumption more than five times a week and a lower risk of MS [29].

Vitamin K, found primarily in green leafy vegetables, may be beneficial for MS, since it is required for sphingolipid metabolism, cell membranes, remyelination, and the formation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells [8, 33,34,35,36]. The fermentation process of gut microbiota on vegetables leads to short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) synthesis. SCFAs may have immunomodulatory functions, such as gut epithelial cell integrity, inducing the regulatory T cell differentiation [37,38,39], decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines production through stimulation of G-protein-coupled receptors and histone deacetylase inhibition [40], and elevating the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 [41, 42]. Cruciferous vegetables are an excellent source of the amino acid tryptophan. The tryptophan metabolites activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), leading to various effects on the peripheral immune system [43]. Numerous of these metabolites can pass through the blood–brain barrier and activate AhR on astrocytes. This process leads to nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-Kb) suppression, thus reducing monocyte enrolment, microglial activation, and neurotoxicity in the immediate environment [38, 44, 45]. Vegetable flavonoids also act as AhR agonists [46]. They also exert immunomodulatory and neurodegenerative effects through several additional pathways [47, 48]. Numerous studies have shown the efficacy of various flavonoid compounds in MS animal models, including neuroprotection [49, 50] and even remyelination promotion [51, 52]. Vegetables are also a good source of antioxidants and prebiotics, which can inactivate NF-kB and enhance intestinal microbial balance [42, 53]. Polyphenols in vegetables may also lead to downregulation of the synthesis of the pro-inflammatory molecule [42].

The current study showed a significant relationship between bean consumption and MS risk. In contrast, a pilot study on 20 RRMS patients showed that, except for potatoes and legumes, increasing vegetable consumption by one cup equivalent reduced the risk of relapse by 50% [54]. In this study, consumption of beans was also in negative correlation with MS odds. Like vegetables, beans are a great source of polyphenols that have anti-inflammatory effects [55].

Based on the current study outcomes, fast food and fried food consumption, rich in fat, especially saturated fat, is significantly associated with a greater odds of MS. According to the present outcomes, fast fried food consumption more than once per week increased the odds of MS by 32.8 times compared to eating this type of food less than once a week. The high prevalence of MS in Western nations might possibly be attributed to diets rich in sodium, animal fat, red meat, and fried foods [42]. According to the available evidence, a diet rich in animal or saturated fats may be associated with a higher risk of MS [56, 57]. The consumption of saturated fats is positively associated with increased inflammation and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) [58]. According to Tettey et al., increased adiposity, non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and the total cholesterol to HDL ratio are all linked with a greater disability progression rate in the long term. Increased adiposity and triglycerides are linked with relapse but not conversion to MS [59]. Weinstock-Guttman et al. showed a connection between lipid profile parameters, especially LDL-C and total cholesterol (TC) levels, with inflammatory MRI activity measurements in early MS [60]. According to Weinstock-Guttman et al. in another study, increased LDL, TC, and triglyceride levels are linked with worsening disability in MS patients [61]. Saturated fats affect the innate immune system by activating pro-inflammatory toll-like receptors, resulting in an enhanced NF-Kb inflammatory pathway [38, 62]. Saturated fats may also increase endotoxin, leading to an enhanced NF-kB pathway [38, 63]. The adaptive immune system is similarly significantly impacted by a high-fat diet. In a mouse model of MS that had been given a Western high fat diet, spinal cord production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1B, IL-6, and interferon, and T cell and macrophage infiltration, increased [38, 64]. Long-chain fatty acids found in processed foods may support the differentiation of naive T cells into pro-inflammatory TH1 (T helper) and TH17 cells [38, 41]. MIND can add more detail about the amount of recommended fast fried food intake (e.g., French fries and chicken nuggets) for MS prevention.

This research observed a strong significant negative relationship between sweets and pastry intake and the odds of MS, with MS odds being about ten times greater in individuals consuming more than seven servings of sweets per week in adjusted models. Western-style diets typified by sugar-sweetened beverages exacerbate inflammation. This kind of diet stimulates human cell metabolism toward biosynthetic pathways, including the synthesis of arachidonic acid and its pro-inflammatory byproducts that result in gut microbiota imbalance, altered gut immunity, and low-grade systemic inflammation [42]. A diet containing high-sugar and refined carbohydrates is linked with postprandial inflammation [42, 65,66,67].

In the adjusted model, cheese consumption was significantly associated with higher odds of MS. In this study, all kinds of cheese, including low-fat and high-fat, are included in cheese. According to the HOLISM study, dairy consumption was positively associated with relapse rate [30]. However, a case–control study in Iran compared the consumption of low-fat dairy, including cheese, between healthy individuals and patients with MS and reported higher consumption of low-fat dairy products in patients with MS [29]. Although calcium level may be a protective factor in neurological diseases [68], saturated fats promote the NF-kB pathway and the innate immune system [38, 62, 63].

Butter and stick margarine, which are included as unhealthy components in the MIND diet [16], were associated with a lower odds of MS in this study. According to previous research, dietary fat may negatively affect the risk of MS [69]. This result would be due to the different lipogenic characteristics of hard and soft margarine. In the dietary questionnaire used in this study, all the kinds of margarine consumed by individuals were just called 'margarine', which may have affected the result [70].

Poultry as a healthy MIND diet component [16] was associated with a higher odds of MS. In a previous study, no significant association was seen between poultry (including chicken with and without skin) and MS risk [71]. The method of cooking (boiled, steamed, or fried in oil) may have affected the result observed.

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, there has been no prior research on the MIND diet and the odds of MS. We considered just newly diagnosed cases to minimize recall bias. The person who completed the FFQ was unaware of the individual’s presence in the case or the control group. The study had an acceptable sample size, and the control group individuals were similar to the cases in terms of demographic variables. The clinically isolated syndrome affects the dietary pattern of patients; therefore, these patients were not included in the study, and only those with RRMS were recruited.

However, we had some limitations. Participants were not age-matched and were selected from the hospital. Patients with MS from the hospital do not represent those in the community, which affects the issue of generalizability. The study lacked data on education levels, socioeconomic status, physical activity, and previous infection or vaccination history. It would also be better to consider information about other factors, such as the serum level of vitamin D.

Conclusions

Taken together, the current findings indicated that adherence to the MIND diet and its factors, including green leafy vegetables, other vegetables, and beans, is associated with reduced odds of MS. Butter and stick margarine, which assumes an unhealthy MIND component, were associated with lower odds, but this result may be due to the misclassification of soft and hard margarine as a whole group. In addition, high consumption of cheese, pastries and sweets, and fried/fast foods leads to elevated odds of MS. Poultry as a healthy component was also associated with higher odds. Therefore, it seems that following the MIND diet may be a beneficial approach for preventing MS. However, further well-designed randomized clinical trials are needed to make a recommendation for routine adherence to the MIND diet in patients with MS or to prevent MS.

References

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372(9648):1502–17.

Thompson AJ, Baranzini SE, Geurts J, Hemmer B, Ciccarelli O. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2018;391(10130):1622–36.

Heydarpour P, Khoshkish S, Abtahi S, Moradi-Lakeh M, Sahraian MA. Multiple sclerosis epidemiology in Middle East and North Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;44(4):232–44.

Mirmosayyeb O, Shaygannejad V, Bagherieh S, Hosseinabadi AM, Ghajarzadeh M. Prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS) in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci. 2021;43(1):233–41.

Ransohoff RM, Hafler DA, Lucchinetti CF. Multiple sclerosis—a quiet revolution. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(3):134–42.

Lublin FD, Coetzee T, Cohen JA, Marrie RA, Thompson AJ. The 2013 clinical course descriptors for multiple sclerosis: a clarification. Neurology. 2020;94(24):1088–92.

Mahad DH, Trapp BD, Lassmann H. Pathological mechanisms in progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):183–93.

Chenard CA, Rubenstein LM, Snetselaar LG, Wahls TL. Nutrient composition comparison between a modified paleolithic diet for multiple sclerosis and the recommended healthy uS-style eating pattern. Nutrients. 2019;11(3):537.

Mohammadifard N, Sarrafzadegan N, Nouri F, Sajjadi F, Alikhasi H, Maghroun M, et al. Using factor analysis to identify dietary patterns in Iranian adults: Isfahan healthy heart program. Int J Public Health. 2012;57(1):235–41.

Esposito S, Sparaco M, Maniscalco G, Signoriello E, Lanzillo R, Russo C, et al. Lifestyle and Mediterranean diet adherence in a cohort of Southern Italian patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;47:102636.

Materljan E, Materljan M, Materljan B, Vlačić H, Barićev-Novaković Z, Sepčić J. Multiple sclerosis and cancers in Croatia—a possible protective role of the “Mediterranean diet.” Coll Antropol. 2009;33(2):539–45.

Moravejolahkami AR, Paknahad Z, Chitsaz A, Hojjati Kermani MA, Borzoo-Isfahani M. Potential of modified Mediterranean diet to improve quality of life and fatigue severity in multiple sclerosis patients: a single-center randomized controlled trial. Int J Food Prop. 2020;23(1):1993–2004.

Razeghi-Jahromi S, Doosti R, Ghorbani Z, Saeedi R, Abolhasani M, Akbari N, et al. A randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of a mediterranean-like diet in patients with multiple sclerosis-associated cognitive impairments and fatigue. Curr J Neurol. 2020;19(3):112.

Sand IK, Benn EK, Fabian M, Fitzgerald KC, Digga E, Deshpande R, et al. Randomized-controlled trial of a modified Mediterranean dietary program for multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;36:101403.

Rotstein DL, Cortese M, Fung TT, Chitnis T, Ascherio A, Munger KL. Diet quality and risk of multiple sclerosis in two cohorts of US women. Mult Scler J. 2019;25(13):1773–80.

Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(9):1007–14.

Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Barnes LL, Bennett DA, et al. MIND diet slows cognitive decline with aging. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(9):1015–22.

Berendsen AM, Kang JH, Feskens EJ, de Groot C, Grodstein F, van de Rest O. Association of long-term adherence to the mind diet with cognitive function and cognitive decline in American women. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(2):222–9.

Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, Carroll WM, Coetzee T, Comi G, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162–73.

Asghari G, Rezazadeh A, Hosseini-Esfahani F, Mehrabi Y, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Reliability, comparative validity and stability of dietary patterns derived from an FFQ in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(6):1109–17.

Esfahani FH, Asghari G, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Reproducibility and relative validity of food group intake in a food frequency questionnaire developed for the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. J Epidemiol. 2010;20(2):150–8.

Mirmiran P, Esfahani FH, Mehrabi Y, Hedayati M, Azizi F. Reliability and relative validity of an FFQ for nutrients in the Tehran lipid and glucose study. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(5):654–62.

Willett W, Hu F. Anthropometric measures and body composition. Nutrepidemiol. 2013;15:213–41.

Azar M, Sarkisian E. Food composition table of Iran: national nutrition and food research institute. Tehran: Shaheed Beheshti University; 1980.

USDA national nutrient database for standard reference (2019). http://www.ars.usda.gov/,r.c.a.a.andnews/docs.htm?docid=18880. Accessed Jan 2021

Sand IK, Fitzgerald KC, Gu Y, Brandstadter R, Riley CS, Buyukturkoglu K, et al. Dietary factors and MRI metrics in early multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2021;53:103031.

Jahromi SR, Toghae M, Jahromi MJR, Aloosh M. Dietary pattern and risk of multiple sclerosis. Iran J Neurol. 2012;11(2):47.

Sedaghat F, Jessri M, Behrooz M, Mirghotbi M, Rashidkhani B. Mediterranean diet adherence and risk of multiple sclerosis: a case–control study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2016;25(2):377–84.

Bagheri M, Maghsoudi Z, Fayazi S, Elahi N, Tabesh H, Majdinasab N. Several food items and multiple sclerosis: a case–control study in Ahvaz (Iran). Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2014;19(6):659.

Hadgkiss EJ, Jelinek GA, Weiland TJ, Pereira NG, Marck CH, Van Der Meer DM. The association of diet with quality of life, disability, and relapse rate in an international sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Nutr Neurosci. 2015;18(3):125–36.

Marck CH, Probst Y, Chen J, Taylor B, van der Mei I. Dietary patterns and associations with health outcomes in Australian people with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:1506–14.

McKellar S, Horsley P, Chambers R, Bauer J, Vendersee P, Clarke C, et al. Development of the diet habits questionnaire for use in cardiac rehabilitation. Aust J Prim Health. 2008;14(3):43–7.

Ferland G. Vitamin K and the nervous system: an overview of its actions. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(2):204–12.

Ferland G, editor. Vitamin K and brain function. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. New York: Thieme; 2013.

Goudarzi S, Rivera A, Butt AM, Hafizi S. Gas6 promotes oligodendrogenesis and myelination in the adult central nervous system and after lysolecithin-induced demyelination. ASN Neuro. 2016;8(5):1759091416668430.

Popescu DC, Huang H, Singhal NK, Shriver L, McDonough J, Clements RJ, et al. Vitamin K enhances the production of brain sulfatides during remyelination. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0203057.

Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446–50.

Katz SI. The role of diet in multiple sclerosis: mechanistic connections and current evidence. Curr Nutr Rep. 2018;7(3):150–60.

Salari A, Mahdavi-Roshan M, Kheirkhah J, Ghorbani Z. Probiotics supplementation and cardiometabolic risk factors: a new insight into recent advances, potential mechanisms, and clinical implications. PharmaNutrition. 2021;16:100261.

Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients. 2011;3(10):858–76.

Haghikia A, Jörg S, Duscha A, Berg J, Manzel A, Waschbisch A, et al. Dietary fatty acids directly impact central nervous system autoimmunity via the small intestine. Immunity. 2015;43(4):817–29.

Riccio P, Rossano R. Nutrition facts in multiple sclerosis. ASN Neuro. 2015;7(1):1759091414568185.

Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Quintana FJ. Regulation of the immune response by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Immunity. 2018;48(1):19–33.

Rothhammer V, Quintana FJ. Environmental control of autoimmune inflammation in the central nervous system. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;43:46–53.

Rothhammer V, Mascanfroni ID, Bunse L, Takenaka MC, Kenison JE, Mayo L, et al. Type I interferons and microbial metabolites of tryptophan modulate astrocyte activity and central nervous system inflammation via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nat Med. 2016;22(6):586–97.

Xue Z, Li D, Yu W, Zhang Q, Hou X, He Y, et al. Mechanisms and therapeutic prospects of polyphenols as modulators of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Food Funct. 2017;8(4):1414–37.

McKenzie C, Tan J, Macia L, Mackay CR. The nutrition-gut microbiome-physiology axis and allergic diseases. Immunol Rev. 2017;278(1):277–95.

Spagnuolo C, Moccia S, Russo GL. Anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids in neurodegenerative disorders. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;153:105–15.

Hashimoto M, Yamamoto S, Iwasa K, Yamashina K, Ishikawa M, Maruyama K, et al. The flavonoid Baicalein attenuates cuprizone-induced demyelination via suppression of neuroinflammation. Brain Res Bull. 2017;135:47–52.

Zhang Q, Li Z, Wu S, Li X, Sang Y, Li J, et al. Myricetin alleviates cuprizone-induced behavioral dysfunction and demyelination in mice by Nrf2 pathway. Food Funct. 2016;7(10):4332–42.

Skaper SD, Barbierato M, Facci L, Borri M, Contarini G, Zusso M, et al. Co-ultramicronized palmitoylethanolamide/luteolin facilitates the development of differentiating and undifferentiated rat oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(1):103–14.

Zhang Y, Yin L, Zheng N, Zhang L, Liu J, Liang W, et al. Icariin enhances remyelination process after acute demyelination induced by cuprizone exposure. Brain Res Bull. 2017;130:180–7.

Ghorbani Z, Pourshams A, Fazeltabar MA, Sharafkhah M, Poustchi H, Hekmatdoost A. Major dietary protein sources in relation to pancreatic cancer: a large prospective study. Arch Iran Med. 2016.

Saresella M, Mendozzi L, Rossi V, Mazzali F, Piancone F, LaRosa F, et al. Immunological and clinical effect of diet modulation of the gut microbiome in multiple sclerosis patients: a pilot study. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1391.

Riccio P, Rossano R. Diet, gut microbiota, and vitamins D + A in multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15(1):75–91.

Swank RL, Lerstad O, Strøm A, Backer J. Multiple sclerosis in rural Norway: its geographic and occupational incidence in relation to nutrition. N Engl J Med. 1952;246(19):721–8.

Perković O, Jurjević A, Rudež J, Antončić I, Bralić M, Kapović M. The town of Čabar, Croatia, a high risk area for multiple sclerosis-analytic epidemiology of dietary factors. Coll Antropol. 2010;34(2):135–40.

Ruiz-Núñez B, Dijck-Brouwer DJ, Muskiet FA. The relation of saturated fatty acids with low-grade inflammation and cardiovascular disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2016;36:1–20.

Tettey P, Simpson S, Taylor B, Ponsonby A-L, Lucas RM, Dwyer T, et al. An adverse lipid profile and increased levels of adiposity significantly predict clinical course after a first demyelinating event. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(5):395–401.

Weinstock-Guttman B, Zivadinov R, Horakova D, Havrdova E, Qu J, Shyh G, et al. Lipid profiles are associated with lesion formation over 24 months in interferon-β treated patients following the first demyelinating event. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(11):1186–91.

Weinstock-Guttman B, Zivadinov R, Mahfooz N, Carl E, Drake A, Schneider J, et al. Serum lipid profiles are associated with disability and MRI outcomes in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8(1):1–7.

Huang S, Rutkowsky JM, Snodgrass RG, Ono-Moore KD, Schneider DA, Newman JW, et al. Saturated fatty acids activate TLR-mediated proinflammatory signaling pathways [S]. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(9):2002–13.

Mani V, Hollis JH, Gabler NK. Dietary oil composition differentially modulates intestinal endotoxin transport and postprandial endotoxemia. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2013;10(1):1–9.

Timmermans S, Bogie JF, Vanmierlo T, Lütjohann D, Stinissen P, Hellings N, et al. High fat diet exacerbates neuroinflammation in an animal model of multiple sclerosis by activation of the renin angiotensin system. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2014;9(2):209–17.

Erridge C, Attina T, Spickett CM, Webb DJ. A high-fat meal induces low-grade endotoxemia: evidence of a novel mechanism of postprandial inflammation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(5):1286–92.

Ghanim H, Abuaysheh S, Sia CL, Korzeniewski K, Chaudhuri A, Fernandez-Real JM, et al. Increase in plasma endotoxin concentrations and the expression of Toll-like receptors and suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 in mononuclear cells after a high-fat, high-carbohydrate meal: implications for insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(12):2281–7.

Margioris AN. Fatty acids and postprandial inflammation. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12(2):129–37.

Emard JF, Thouez JP, Gauvreau D. Neurodegenerative diseases and risk factors: a literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(6):847–58.

Wang DD, Li Y, Chiuve SE, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rimm EB, et al. Association of specific dietary fats with total and cause-specific mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(8):1134–45.

Zock PL, Katan MB. Butter, margarine and serum lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis. 1997;131(1):7–16.

Zhang SM, Willett WC, Hernán MA, Olek MJ, Ascherio A. Dietary fat in relation to risk of multiple sclerosis among two large cohorts of women. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(11):1056–64.

Nouri-Majd S, Salari-Moghaddam A, Keshteli AH, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P. The association between adherence to the MIND diet and irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis. 2021;5:1.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants in the present study. We extend our gratitude to the staff of the MS clinic of Sina University Hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) (Grant no. 962667). NIMAD had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, and writing the study manuscript. No funding or sponsorship was received for publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ Contributions

SRJ and ZG designed and supervised the study, acquired funding, collected data, interpreted study findings, and wrote, critiqued, and edited the manuscript. MN conducted data analyses, interpreted study findings, and wrote the manuscript. ANM, MG, NR, ZS, SS, AH and AG collected data and acquired funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Morvarid Noormohammadi, Zeinab Ghorbani, Abdorreza Naser Moghadasi, Zahra Saeedirad, Sahar Shahemi, Milad Ghanaatgar, Nasim Rezaiemanesh, Azita Hekmatdoost, Amir Ghaemi, and Soodeh Razeghi Jahromi declare that they have no competing interests.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The research protocol of the present study was confirmed by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute for Medical Research Development (NIMAD) (Research number = 962667). Also, the research ethics committee of NIMAD authorized the study (Ethics code: IR.NIMAD.REC.1396.320). Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its subsequent revisions were followed in the conduct of the research. All individuals have given written permission to participate in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noormohammadi, M., Ghorbani, Z., Naser Moghadasi, A. et al. MIND Diet Adherence Might be Associated with a Reduced Odds of Multiple Sclerosis: Results from a Case–Control Study. Neurol Ther 11, 397–412 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00325-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00325-z