Abstract

Introduction

Timely and effective resolution of multiple sclerosis (MS) relapse is critical to minimizing residual deficits, which can result in neurologic disability. Oral corticosteroids (OCS) and intravenous corticosteroids [intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP)] are earlier line treatments; alternatives include repository corticotropin injection (RCI; H.P. Acthar® Gel), plasmapheresis (PMP), and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Contemporary insight into the use of relapse treatments and their effectiveness is needed.

Objective

To evaluate relapse rates, frequency of treatments used, and treatment effectiveness (i.e., relapse resolution).

Methods

A retrospective analysis of patients ages 18–89 years experiencing MS relapse from 1 January 2008 to 30 June 2015 was conducted using administrative claims data. MS relapse was defined based on established claims-based methodology. The first claim for relapse treatment (i.e., prescription or administration) was used to designate the treatment group and relapse date, respectively. Relapses occurring ≤ 30 days were considered an episode. The first relapse episode was identified for every patient. Treatment was deemed effective in resolving the relapse if no additional relapses followed within the episode; otherwise, the relapse was considered unresolved. A 5-day OCS taper following IVMP administration, designated IVMP ± OCS, was allowed. Relapse frequency, treatment use, and relapse resolution were quantified. Relapse resolution was likewise evaluated in patients continuously enrolled for 12 months before and after first treatment with RCI or PMP/IVIG, with PMP/IVIG administrations within 7 days of each other being considered a single course of therapy.

Results

During the study period, 9574 patients experienced ≥ 1 relapse; 26.0% of patients had ≥ 2 relapses/year. The mean number of relapse episodes was 2.6 over a mean follow-up of 2.7 years for an annualized relapse rate of 1.0. Corticosteroids were the first treatment used in 90.4% of relapses (OCS = 51.8%, IVMP = 38.6%), followed by IVIG (6.0%), RCI (2.2%) and PMP (1.5%). The proportion of patients achieving relapse resolution with their first treatment was 90.5% with OCS (n = 5710), 47.8% with IVMP ± OCS (n = 3425), 96.9% with RCI (n = 195), 50.7% with PMP (n = 73), and 43.9% with IVIG (n = 171). Among continuously enrolled patients (n = 373), relapse resolution was 95.7% with RCI (n = 232) and 66.0% with PMP/IVIG (n = 141); significant cohort differences were observed.

Conclusions

As demonstrated in other studies, OCS were generally effective. However, real-world effectiveness varied with other treatments. Relapse resolution of the first treatment with OCS was higher than with IVMP ± OCS; similarly, relapse resolution was higher with RCI as the first treatment than with PMP/IVIG. Results demonstrate RCI’s effectiveness in appropriate patients. Limitations pertaining to claims-based research apply.

Funding

Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals (Bedminster, NJ).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A multiple sclerosis (MS) relapse, as per the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS), is considered any new or acutely worsening neurologic symptoms with objective evidence that [1, 2] is consistent with inflammation and demyelination; lasts for more than 24 hours; is separated by at least 30 days from the onset of the last relapse; is not related to an infection, fever, or other stresses; or has no other explanation [3]. MS relapses adversely impact functional status and health-related quality of life [4]. Residual deficits from acute relapses and gradual disease progression accumulate, resulting in neurologic disability [5].

Corticosteroids (CS), including self-administered oral CS (OCS) and provider-administered intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP), are first-line MS relapse treatments with purportedly similar efficacy [3, 6, 7]. Treatment with IVMP requires multiple infusions, which can be more costly and less convenient than OCS and may impact daily life [6, 7]. Given the majority of clinical studies for the treatment of MS relapse [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] were conducted before the widespread availability and diversification of disease-modifying therapy (DMT), updated effectiveness information is lacking [5].

Currently, there is no standard approach to relapse treatment when CS are inappropriate or ineffective [3–5, 17], although a treatment algorithm has recently been proposed by Berkovich [1]. Corticosteroid alternatives include: (1) repository corticotropin injection (the only branded RCI available in the US; H.P. Acthar® Gel), approved for treatment of MS relapse in the US, which can be self-administered; (2) plasmapheresis (PMP), recommended by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) as second-line treatment for steroid-resistant exacerbations in relapsing forms of MS; and (3) intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), an off-label treatment sometimes used to treat relapses that do not respond to CS, with limited supporting evidence [3, 18]. As stated by Stoppe and colleagues [5], “evaluating how well severity and duration of the exacerbation are improved represents the most valuable and clinically meaningful assessment in determining the efficacy of relapse treatment.”

Our study objective was to evaluate MS relapse rates, use of relapse treatments, and relapse treatment effectiveness in resolving relapse. In a cohort of continuously enrolled patients on corticosteroid alternatives RCI, PMP, and IVIG, relapse treatment effectiveness was again evaluated, and the cohorts were characterized and compared.

Methods

This retrospective study used administrative health insurance claims data from a US health plan from 1 January 2008 to 30 June 2015. The study protocol was reviewed by the Advarra Institutional Review Board, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, and waivers of patient authorization/informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization were granted.

Data Source

Administrative claims data from Humana Inc., a US health and wellness plan, were used. The Humana Research Database (Humana Inc., Louisville, KY) contains administrative health insurance claims data for approximately 22 million individuals in the US who are covered by Humana Medicare Advantage and Prescription Drug (MAPD) plans, standalone Prescription Drug Plans (PDP), Medicaid plans, and commercial plans, with a high proportion of individuals from Texas, Florida, and Ohio. Medical claims data include diagnosis and procedure codes associated with all-cause hospital admissions, physician visits, other outpatient visits/procedures, and emergency department (ED) visits. Pharmacy claims data include National Drug Codes (NDCs) and outpatient prescription drug fills. Enrollment data include health plan coverage start and end dates, plan type, and patient demographic characteristics, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and geographical region.

Study Population Selection

All patients were ≥ 18 years of age as of the first relapse treatment received. Only those patients enrolled in a health insurance plan with medical and pharmacy benefits were included. Patients > 89 years old were omitted to protect patient privacy.

Patients using a relapse treatment (OCS, i.e., prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, or dexamethasone), IVMP, and corticosteroid alternatives RCI, PMP, and IVIG) comprised the first patient cohort of interest; no minimum health plan enrollment was required (i.e., open enrollment was allowed). This cohort was designated as the open enrollment cohort.

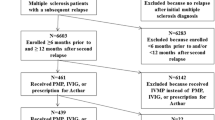

A second cohort of patients receiving the corticosteroid alternatives RCI, PMP, or IVIG, with a minimum continuous health plan enrollment of 12 months before and 12 months after the first relapse (designated baseline and follow-up periods, respectively), was evaluated. Patients who received RCI and either PMP or IVIG within 30 days of the first relapse were excluded. Because of the small numbers of patients treated with PMP and IVIG, patients were combined into a single group (PMP/IVIG), as done in a previous study [19].

Relapses, Treatment Regimens, and Relapse Resolution

MS relapse was defined as an inpatient admission or hospitalization with a principal diagnosis of MS [International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (i.e., ICD-9-CM of 340.xx)] or an outpatient visit or emergency department (ED) visit with a diagnosis of MS, followed by a medical or pharmacy claim for a relapse treatment of interest within 30 days [19, 20].

A novel approach to evaluating relapse resolution was used by building upon the established claims-based definition above with an additional component, i.e. a 30-day time frame to demarcate a new relapse event, as per the NMSS relapse definition [3]. This 30-day time frame was used as a marker to correlate MS relapse as either one unresolved relapse if within 30 days of the first visit for relapse or another new relapse if > 30 days from the first visit for relapse. Using this additional component, we assumed that patients who return within 30 days of their prior visit for more MS relapse medication do so because of a persistent or unresolved prior relapse. Our methodology was to determine the first observed relapse episode for each patient. Then, all relapses identified within 30 days of the first relapse were considered interrelated (i.e., as an episode) and otherwise new. During the episode, all relapse treatments of interest were recorded. The first claim for treatment was used to designate the treatment group and the relapse date. Treatment was considered effective in resolving the relapse if no additional relapses followed; if additional relapses followed, treatment was considered ineffective and the relapse unresolved.

Any prescription of OCS, per the MS relapse definition above, was considered a relapse treatment; there was no dosage requirement. Since IVMP, PMP, and IVIG are administered in a healthcare setting as part of a regimen, up to a 5-day OCS taper was allowed following IVMP administration without impacting relapse resolution (designated IVMP ± OCS). In addition, because PMP and IVIG may each be given as courses of therapy involving multiple administrations, administrations occurring within 7 days of each other were considered part of the same course; these did not count as unresolved relapses [18]. PMP/IVIG administrations within 14 days of each other were also similarly evaluated as a sensitivity analysis.

Patient Characteristics and Healthcare Resource Utilization (HCRU)

Patient demographics, health plan, clinical characteristics, and HCRU were evaluated. Demographic characteristics as of the date of the first relapse were assessed, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, geographical region, and health plan type. During baseline and follow-up periods, the following were evaluated: clinical indicators, including functional impairment measures of the Expanded Disability Status Scale Disability-Derived Impairments score (EDSS-DDI), related neurologic impairment indicators (RNII), and use of dalfampridine (Ampyra®; indicated for walking disability); use of DMTs (including interferon beta-1a, interferon beta-1b, peginterferon, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate, alemtuzumab, or natalizumab) and DMT adherence (proportion of days covered or PDC); and HCRU, including inpatient admissions, outpatient visits, ED use, rehabilitation services, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) services [21, 22].

Analysis

Among the first “open enrollment” cohort, the frequency of relapse, use of relapse treatment, and relapse resolution with first treatment were evaluated. Relapse resolution by treatment was also evaluated in the second “continuous enrollment” cohort taking corticosteroid alternatives RCI and PMP/IVIG. The RCI and PMP/IVIG cohorts were then characterized and compared.

Descriptive analyses were conducted. Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables, and t-tests were used for continuous variables between groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Study results were reported in the aggregate. All data handling and analyses were conducted by Humana’s CHI study team using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously collected data and did not explicitly precipitate human or animal subjects. The study protocol was approved by Schulman Institutional Review Board (now Advarra).

Results

Study population selection for the second “continuously enrolled” cohort is shown in Fig. 1.

The number of relapse episodes and proportion of relapse episodes by first treatment received among the first “open enrollment” cohort are shown in Table 1. A total of 25,162 relapse episodes and 9574 patients experiencing relapse were identified with a mean follow-up period of 2.7 years per patient for an annualized relapse rate (ARR) of 1.0 (mean relapse episodes/patient = 2.6). In this cohort, 81.4% had ≥ 1 relapse episode per year and 26.0% had ≥ 2 relapse episodes per year; moreover, 36.9% (or 3532) experienced ≥ 1 unresolved relapse.

Relapse treatment utilization is shown in Table 1. Corticosteroids were the first treatment received in 90.4% of all relapse episodes (51.8% OCS, 38.6% IVMP), followed by IVIG (6.0%), RCI (2.2%), and PMP (1.5%).

Resolution of the first relapse for both patient cohorts is presented in Table 2. Relapse resolution with first treatment of OCS was 90.5% (n = 5710); with the first treatment of IVMP ± OCS, it was 47.8% (n = 3425). Among corticosteroid alternatives, relapse resolution with the first treatment of RCI was 96.9% (n = 195), with IVIG was 43.9% (n = 171), and with PMP was 50.7% (n = 73).

A total of 373 patients with continuous enrollment who received the RCI or PMP/IVIG were identified. Resolution of the index relapse with the first treatment was 95.7% with RCI (n = 232), and 66.0% with PMP/IVIG (n = 141) as a course of therapy. Altering the final PMP/IVIG course of therapy to allow for administrations within 14 days of each other, vs. 7 days of each other, varied results by < 1%.

The characteristics of continuously enrolled patients receiving RCI and PMP/IVIG are presented in Table 3. Significantly higher proportions of female (78.9% vs. 69.5%) and Medicare Advantage enrollees (88.4% vs. 64.5%) were observed in patients receiving RCI vs. PMP/IVIG; however, no significant difference was found in age (51.6 vs. 53.1 years).

In Table 4, significant cohort differences in continuously enrolled patients receiving RCI vs. PMP/IVIG are shown. These remained consistent, from the baseline period (all P < 0.05) through the follow-up period (all P ≤ 0.02). Compared with those receiving PMP/IVIG, patients receiving RCI had significantly greater clinical and functional impairment indicators during baseline [EDSS-DDI scores (1.0 vs. 0.7), RNII scores (2.2 vs. 1.9), and dalfampridine use (14.7% vs. ***, counts were suppressed per CHI policy)] and follow-up [EDSS-DDI scores (1.1 vs. 0.8), RNII scores (2.3 vs. 1.8), and dalfampridine use (19.8% vs. ***)]. A higher proportion of those receiving RCI compared with those receiving PMP/IVIG were taking DMTs during baseline (66.4% vs. 29.8%) and follow-up (75.0% vs. 27.7%). Among DMT users, PDC was not found to be different between groups during follow-up. Patients receiving RCI had significantly fewer mean all-cause inpatient admissions and outpatient visits during baseline (IP: 0.3 vs. 0.8, OP: 29.3 vs. 35.9) and follow-up (IP: 0.4 vs. 0.6; OP: 32.7 vs. 45.4). No significant differences were seen in use of the ED or rehabilitation services, or in the occurrence of MRI procedures, between treatment groups during baseline and follow-up time periods.

Discussion

Published literature indicates an unmet need for patients of achieving relapse resolution in a timely and comprehensive manner, ideally with their first treatment and with their first round of treatment [23, 24], i.e. without trying mutiple treatments nor multiple rounds of treatment. Survey results reported from the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry participants indicate an unmet need in relapse therapies; a “sizeable” percentage of patients reported lack of treatment effectiveness with CS at 1 month and 3 months and that corticosteroid treatment had no effect on or worsened their relapse symptoms [25, 26]. In a study by Nickerson and Marrie, 30% of patients given IVMP and 38% of those given OCS reported that their treatment worsened their relapse symptoms or had no effect [25]. In contrast, we observed unresolved relapses among a low percentage of patients, particularly with OCS (9.5%) and RCI (3.1%). The NARCOMS data were patient-reported and based on patient survey, whereas this study uses administrative claims data; both study designs have their advantages and disadvantages, yet provide important insights.

Prior research indicates patients with longer relapses are significantly more likely to feel negatively about treatment [26], which may ultimately affect therapeutic compliance and/or treatment-seeking behavior. In keeping, recent study of neurology clinic patients showed increasing prevalence of escalating relapse treatment, in which a second course of treatment was given for an unresolved or refractory relapse [5]. Relapse resolution is also of critical importance given that residual deficits caused by refractory or protracted relapse, along with those related to inevitable disease progression, may contribute to neurologic disability [5].

Our study quantified the magnitude of unresolved relapse and relapse treatment effectiveness in resolving relapse using health plan administrative claims data. The coverage policy of the health plan for the treatment of MS relapse at the time of this study was consistent with NMSS guidelines, which promote the use of CS or alternative therapies in cases of corticosteroid contraindications or corticosteroid intolerance [3]. More than 90% of relapses were first treated with CS (OCS or IVMP), in keeping with the standard of care and insurance medical policy. Of the approximately 10% of relapses first treated with corticosteroid alternatives, IVIG was used most often. Although IVIG lacks consistent supportive evidence, it may be considered for relapses in certain cases such as during pregnancy and afterward [2, 3, 27]. Reasons for medication use could not be determined using this data source.

An ARR of 1.0 was determined among patients who experienced relapse (i.e., all patients experienced at least 1 relapse during the study). This rate is higher than usually reported by other publications, which can calculate ARR differently, i.e., among all MS patients regardless of the incidence of relapse and length of follow-up [28,29,30]. Other research also illustrates variable relapse frequency among patients, i.e., with one study indicating > 20% of relapsing patients reporting more than two relapses in a year [31]. Of patients who experienced relapse in our study, over one-third experienced at least one unresolved relapse and required additional healthcare visits and relapse treatments within 30 days to resolve their relapse.

To quantify relapse treatment effectiveness in resolving relapse, two scenarios were evaluated. The first utilized a cohort with open health plan enrollment. Of the treatments of interest, OCS and RCI were found to be most effective in resolving the relapse with the first treatment (i.e., 90.5% and 96.9% of patients, respectively). Relapse resolution was evaluated in a second cohort of patients with continuous enrollment receiving corticosteroid alternatives. Continuous enrollment, a common requirement/approach in observational claims analysis, ensures patients are eligible to receive all relevant sources of care under health insurance benefits, facilitating reliable capture of healthcare use paid for with health insurance [32]. In our study, the continuous enrollment requirement further ensured robust relapse identification. Results of both relapse resolution analyses confirmed a high magnitude of effectiveness with RCI in patients with presumed intolerance or contraindications to CS (96.9% vs. 95.7%).

The mean age (early 50s) and enrollment in Medicare Advantage in patients receiving corticosteroid alternatives may have correlated with longer disease duration, more progressive disease, and/or worse baseline functioning. MS study cohorts typically evaluated within US health plans are often comprised of younger, commercially insured patients. These cohort characteristics may further explain the lower overall DMT use observed here, as no DMTs were approved for use in progressive forms of MS during the study period. Other explanations for the less common use of DMTs in the IVIG/plasma group than in the RCI group could include other unmeasurable factors (i.e., less inflammatory or type of MS) in claims, as these clinical details were not available in this data source. As suggested by the coverage policy, patients taking corticosteroid alternatives were likely intolerant and/or had poor response or nonresponse to corticosteroid treatment and therefore required different therapy. Considering their baseline characteristics, these patients could be impacted even more substantially by MS relapse in the short term and by lingering effects of unresolved MS relapse and its residual burden in the longer term.

Although no significant differences were found in mean age between those receiving corticosteroid alternatives RCI vs. PMP/IVIG, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving RCI were female, enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans, and had significantly increased presence of all MS functional impairment indicators evaluated despite significantly increased use of DMTs. Similarly, this may signal advanced MS disease and worse baseline functioning in RCI-treated patients (e.g., walking impairment) vs. the PMP/IVIG cohort.

Patients who were treated with PMP/IVIG had significantly higher use of all-cause inpatient and outpatient services, although mode of administration associated with an administered therapy would inherently lead to increased HCRU. Specific reasons for the increased HCRU were beyond the scope of the database and our study but should be examined as they may signal other important healthcare considerations and/or complexities. The ability and/or decision to use a therapy that can be self-administered (e.g., RCI) vs. the need and/or decision to have therapy administered under healthcare provider supervision (e.g., PMP/IVIG) may itself be indicative of other important patient care needs and differences.

The distinct lack of comparative studies and lack of an established treatment pathway in MS relapse to-date have been highlighted by the clinical community. An algorithm for the treatment of MS relapse recommended that RCI treatment be considered prior to treatment with PMP/IVIG in appropriate patients [4]. Our study characterizes patients receiving RCI and PMP/IVIG and indicates they may be different in important ways, while underscoring the treatment effectiveness with each in alignment with Berkovich’s proposal [4]. The results of this study are an important start toward evaluating an appropriate patient type and supporting a relapse treatment algorithm, given treatment effectiveness results realized by patients receiving CS alternatives.

Relapse resolution is an important measure of treatment efficacy attainment and should be considered in future research focusing on MS relapse. As we have demonstrated, timely and effective relapse resolution with the first relapse treatment should not be assumed. Methodologic consideration should be given concerning how to evaluate one-time treatments vs. treatments requiring repeated administration that could be billed in single or multiple claims (e.g., IVMP daily for 3–5 days following relapse onset) [3]. Implications of treatment regimens (e.g., complexity, mode of administration, inconvenience) should be considered given potential challenges posed to patient compliance and ultimately to healthcare-seeking behavior.

Given the known heterogeneity of MS (e.g., as a disease state, in terms of relapse, as experienced by patients), different patient populations with MS should be evaluated with regard to their relapse frequency, relapse treatment utilization, and relapse resolution by treatment. Patient characteristics should be described to further understand treatment effectiveness for particular patient segments in order to inform more appropriate selection of relapse treatment for patients. Treatment effectiveness should be evaluated across all relapses in a given time frame in patients continuously enrolled in their health plans to increase the robustness of the supporting sample size. However, by virtue of CS being the first-line therapy, sample sizes for CS alternatives will inherently be challenged when assessing corticosteroid alternatives.

Limitations

Administrative health insurance claims data lack clinical detail and indicators (e.g., disease severity, prescribing directions, MS subtype, EDSS, MRI results, disease duration, treatment history); therefore, this information is limited or unavailable to operationalize in our analysis.

Identification of relapses and health behavior from claims data assumes treatment-seeking behavior and use of health insurance on the part of patients. Mild relapses and treatments used outside of health insurance would be likely systematically missed. If a patient did not receive additional relapse treatment, we assumed the relapse was resolved; although additional healthcare-seeking behavior and treatment could be otherwise explained, we anticipate this assumption would affect all treatment groups. Humana health plan data represent a unique population, with a higher proportion of Medicare Advantage enrollees; therefore, our results have limited generalizability to other US health plans.

The first observed relapse may not have been the actual start of the relapse. The start of the relapse and the first treatment associated would impact the therapy to which the relapse was attributed; similarly, the end of the relapse episode may have been missed. Our approach to evaluating relapse resolution was systematic, and the continuous enrollment analysis further mitigated these limitations [4, 33]. The 30-day episode duration we used as an assumption, based on the accepted NMSS definition, may be reconsidered as well.

Variation in treatment regimens would impact the rate of relapse resolution. For example, IVIG and PMP may each be administered as courses of therapy of variable length, involving multiple administrations over the course of a period of time. This underscores the inherent lack of standardization in MS relapse treatment regimens. Here, we implemented an assumption regarding IVIG and PMP use based on the available literature, in the absence of established or widely recommended regimens [4]. IVMP was not evaluated as a course of therapy in this research, which might explain why it seemed less; a 5-day oral CS taper was accounted for as a potential extension of IVMP therapy. Similarly, if oral CS tapering after IVMP therapy occurred over periods > 5 days, relapse effectiveness would likely have been higher than estimated here. Because of small patient counts, PMP- and IVIG-treated patients were combined into one cohort, as done in past research; however, results from the open-enrollment cohort indicate potential effectiveness differences, which should be examined further. Our analysis focused on the most common set of therapies used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis relapse; the frequency of relapse therapy uses vary widely. Despite creating a patient cohort from a multiyear data set from a large US commercial health plan, we were limited by the small sample size of our cohort of interest. The small sample size further limited us from conducting more sophisticated statistical analysis, which requires a larger sample size to obtain precise estimates [34]. As such, only unadjusted analyses of treatment groups could be appropriately conducted, as presented here.

Conclusion

Timely and comprehensive relapse resolution is critical in successful management of MS relapse and in mitigating long-term neurologic disability in a population challenged by their disease and its destructive hallmark of MS relapse. While CS are the standard of care for MS relapse, when inappropriate for use or unsuccessful in resolving relapse, the effectiveness of other therapies must be further considered and understood in order to inform options for patients.

Per our study, relapse treatment effectiveness varies with OCS, IVMP, RCI, PMP, and IVIG. In this large, insured population of patients with MS relapse, 90.5% of relapses were resolved following first treatment with OCS. Relapse resolution in patients receiving RCI was 95.7%, the highest of all relapse treatments evaluated. Cohort differences were observed during the course of analysis; these, along with other factors, may have influenced the effectiveness observed. Given the very high treatment effectiveness of RCI, the characteristics of patients receiving RCI described here, which having presumed intolerance or contraindications to CS per standard practice and per health plan policy, may be suitable for further study toward identification of an appropriate patient type for RCI therapy. Other patient segments must also be evaluated regarding relapse effectiveness to further understand patients who may benefit from treatment with a specific relapse therapy. Based on effectiveness, our study indicates that OCS is an appropriate treatment for most patients; however, in cases where an alternative to CS is required, the observed robust effectiveness suggests consideration of RCI in appropriate patients such as those studied here.

References

Berkovich RR. Acute multiple sclerosis relapse. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016;22(3):799–814.

Thrower BW. Relapse management in multiple sclerosis. Neurologist. 2009;15(1):1–5.

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Relapse Management. 2017. http://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/Managing-MS/Relapse-Management. Accessed 20 Aug 2017.

Berkovich R. Treatment of acute relapses in multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2013;10:97–105.

Stoppe M, Busch M, Krizek L, Bergh FT. Outcomes of MS relapses in the era of disease-modifying therapy. BMC. Neurol. 2017;17:151.

Liu S, Liu X, Chen S, Xiao Y, Zhuang W. Oral versus intravenous methylprednisolone for the treatment of multiple sclerosis relapses: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188644.

Burton JM, O’Connor PW, Hohol M, Beyene J. Oral versus intravenous steroids for treatment of relapses in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD006921.

Abbruzzese G, Gandolfo C, Loeb C. “Bolus” methylprednisolone versus ACTH in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1983;2:169–72.

Alam SM, Kyriakides T, Lawden M, Newman PK. Methylprednisolone in multiple sclerosis: a comparison of oral with intravenous therapy at equivalent high dose. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:1219–20.

Barnes MP, Bateman DE, Cleland PG, et al. Intravenous methylprednisolone for multiple sclerosis in relapse. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48(2):157–9.

Barnes D, Hughes RA, Morris RW, et al. Randomised trial of oral and intravenous methylprednisolone in acute relapses of multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1997;349:902–6.

Durelli L, Cocito D, Riccio A, et al. High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: clinical-immunologic correlations. Neurology. 1986;36(238):243.

Milanese C, Mantia L, Salmaggi A, et al. Double-blind randomized trial of ACTH versus dexamethasone versus methylprednisolone in multiple sclerosis bouts. Clinical, cerebrospinal fluid and neurophysiological results. Eur Neurol. 1989;29(1):10–4.

Milligan NM, Newcombe R, Compston DA. A double-blind controlled trial of high dose methylprednisolone in patients with multiple sclerosis: 1. clinical effects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:511–6.

Sellebjerg F, Frederiksen JL, Nielsen PM, Olesen J. Double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled study of oral, high-dose methylprednisolone in attacks of MS. Neurology. 1998;51:529–34.

Thompson AJ, Kennard C, Swash M, et al. Relative efficacy of intravenous methylprednisolone and ACTH in the treatment of acute relapse in MS. Neurology. 1989;39(7):969–71.

Cortese I, Chaudhry V, So YT, Cantor F, Cornblath DR, Rae-Grant A. Evidence-based guideline update: plasmapheresis in neurologic disorders: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2011;76(3):294–300.

Elovaara I, Kuusisto H, Wu X, Rinta S, Dastidar P, Reipert B. Intravenous immunoglobulins are a therapeutic option in the treatment of multiple sclerosis relapse. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34(2):84–9.

Gold LS, Suh K, Schepman P, et al. Healthcare costs and resource utilization in patients with MS relapses treated with H.P. Acthar Gel Adv Ther. 2016;33:1279–92.

Ollendorf DA, Jilinskaia E, Oleen-Burkey M. Clinical and economic impact of glatiramer acetate versus beta interferon therapy among patients with multiple sclerosis in a managed care population. J Manag Care Pharm. 2002;8(6):469–76.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–52.

Pyenson, B., Fredericks, M., Berrios, M., Mastroianni, M., Han, F. Multiple sclerosis: new perspectives on the patient journey. Milliman Client Report. 2016. http://www.milliman.com/insight/2016/Multiple-sclerosis-New-perspectives-on-the-patient-journey/. Accessed 17 Sept 2019.

Mehr SR, Zimmerman MP. Reviewing the unmet needs of patients with multiple sclerosis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(8):426–31.

Kalincik T. Multiple sclerosis relapses: epidemiology, outcomes and management. A systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;44(4):199–214.

Nickerson M, Marrie RA. 2013. The multiple sclerosis relapse experience: patient-reported outcomes from the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry. BMC. Neurol. 2013;13:119. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-13-119.

Nickerson M, Cofield SS, Tyry T, Salter AR, Cutter GR, Marrie RA. 2015. Impact of multiple sclerosis relapse: The NARCOMS participant perspective. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 4(3),234–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2015.03.005.

Winkelmann A, Rommer PS, Hecker M, Zettl UK. Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in multiple sclerosis: a prospective, rater-blinded analysis of relapse rates during pregnancy and the postnatal period. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25(1):78–85.

Cohan SL, Moses H, Calkwood J, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis who switch from natalizumab to delayed-release dimethyl fumarate: a multicenter retrospective observational study (STRATEGY). Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;22:27–34.

Baroncini D, Mallucci G, Rossi S, et al. The impact of menopause on multiple sclerosis: a multicentre, retrospective, observational study. Multiple Sclerosis J. 2017;23(S3):460.

Comi G, Pozzilli C, Morra VB, et al. One-and two-year annualized relapse rate and NEDA-3 in Italian patients treated with fingolimod: preliminary results from the GENIUS (FinGolimod Real World EvideNce Italian mUlticenter observational Study in Multiple Sclerosis) Study. Neurology. 2018;90(15 suppl):P6.394.

Nazareth TA, Rava AR, Polyakov JL, et al. Relapse prevalence, symptoms, and health care engagement: patient insights from the Multiple Sclerosis in America 2017 survey. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;26:219–34.

Berger ML, Martin BC, Husereau D, Worley K, Allen JD, Yang W, Quon NC, Mullins CD, Kahler KH, Crown W. A questionnaire to assess the relevance and credibility of observational studies to inform health care decision making: an ISPOR-AMCP-NPC Good Practice Task Force report. Value Health. 2014;17(2):143–56.

Chastek BJ, Oleen-Burkey M, Lopez-Breshahan MV. Medical chart validation of an algorithm for identifying multiple sclerosis relapse in healthcare claims. J Med Econ. 2010;13:618–25.

Courvoisier DS, Combescure C, Agoritsas T, Gayet-Ageron A, Perneger TV. Performance of logistic regression modeling: beyond the number of events per variable, the role of data structure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(9):993–1000.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were funded by Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals (Bedminster, NJ).

Medical Writing and other Editorial Support

Medical writing and editorial support, conducted in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines, were provided by Judith S. Hurley, MS, RDN, of Global Outcomes Group, and Emily Kuhl, PhD, of Global Outcomes Group. Expert medical insight to this project was lent by Royce William Waltrip II, MD. The authors thank anonymous reviewers whose comments helped clarify this manuscript.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Tara Nazareth was an employee and stockholder of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals at the time of this study. Tara Nazareth is currently an employee of Celgene. Manasi Datar was an employee of Comprehensive Health Insights, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary Humana, Inc., at the time of the study. Manasi Datar is currently an employee of Boston Healthcare. Tzy-Chyi Yu, MHA, PhD, is an employee and stockholder of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously collected data and did not explicitly precipitate human or animal subjects. The study protocol was approved by Schulman Institutional Review Board (now Advarra).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are proprietary administrative health claims data owned by Humana Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9768050.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Nazareth, T., Datar, M. & Yu, TC. Treatment Effectiveness for Resolution of Multiple Sclerosis Relapse in a US Health Plan Population. Neurol Ther 8, 383–395 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-00156-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-00156-5