Abstract

Introduction

Limited data are available on the real-world effectiveness of newer oral disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) in multiple sclerosis. The purpose of this study was to retrospectively compare the real-world effectiveness of dimethyl fumarate (DMF), fingolimod, teriflunomide, and injectable DMTs in routine clinical practice based on US claims data.

Methods

Patients newly-initiating DMF, interferon beta (IFNβ), glatiramer acetate (GA), teriflunomide, or fingolimod in 2013 were identified in the Truven MarketScan Commercial Claims Databases (N = 6372). Relapse episodes were identified based on a published claim-based algorithm and used to determine the annualized relapse rate (ARR) for the year before and after initiating therapy. Poisson and negative binomial regression was used to determine the adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) for each therapy relative to DMF.

Results

Significant ARR reductions in the year after initiating therapy were reported for DMF and fingolimod (P < 0.0001). Compared with DMF, the adjusted IRR (95% CI) for relapse in the year after initiating therapy was 1.27 (1.10–1.46) for IFNβ, 1.34 (1.17–1.53) for GA, 1.23 (1.05–1.45) for teriflunomide, and 1.03 (0.88–1.21) for fingolimod. Results were consistent across subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Conclusion

These real-world data suggest DMF and fingolimod have similar effectiveness and demonstrate superior effectiveness to IFNβ, GA, and teriflunomide.

Funding: Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, progressive immune-mediated disease of the central nervous system in which inflammation, demyelination, and axonal degeneration lead to loss of neurologic function [1,2,3]. MS affects approximately 2.3 million individuals worldwide and more than 570,000 individuals in the USA [4, 5], and it has a substantial impact on patients' daily living and quality of life [6]. Approximately 85% of people with MS have relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS), characterized by progressive neurologic relapses interspersed with periods of clinical remission [7].

The introduction of oral disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), dimethyl fumarate (DMF), fingolimod, and teriflunomide, is revolutionizing the management of MS, enabling patients with RRMS to achieve significant reductions in the risk of relapses and disease-related disability with daily oral therapy instead of frequent subcutaneous or intramuscular injections [8,9,10,11,12]. Oral therapies offer the advantage of convenience compared with injected medications and have the potential to improve compliance. Given the range of therapies available for the management of RRMS, data on the relative efficacy and safety of new therapies compared with each other and with more well-established DMTs [interferon beta (IFNβ) and glatiramer acetate (GA)] are important to support physician and patient decisions around treatment choice. Currently, there are no head-to-head clinical trials of the available oral therapies and only limited direct comparative data regarding the safety and efficacy of newer oral therapies versus the injected DMTs. Fingolimod provides better efficacy than weekly intramuscular IFNβ [9]; teriflunomide has demonstrated comparable efficacy versus subcutaneous IFNβ administered three times each week [10]; DMF has demonstrated a significantly greater treatment effect on annualized relapse rates (ARRs) compared with once-daily subcutaneous GA in a post hoc analysis of clinical trial data [11].

A number of indirect analyses have been performed concerning the three oral DMTs based on data from their respective clinical trial programs in patients with MS [13, 14]. A mixed-treatment comparison study reported no significant difference in ARR for DMF and fingolimod and superior efficacy for DMF compared with IFNβ, GA, and teriflunomide [13]. A further study using a network meta-analysis approach reported that all three oral DMTs and GA significantly reduced the risk of experiencing at least one relapse over 1 year compared with placebo (P < 0.05); however, the risk reduction achieved with the different IFNβ therapies did not reach statistical significance [14]. Taken together, these results suggest that the oral therapies provide at least comparable efficacy to IFNβ and GA and that DMF and fingolimod may provide superior efficacy compared with teriflunomide.

Although data from clinical trials provide important evidence of the efficacy and safety of new therapies, real-world data are increasingly utilized to support decision-making, based on the value of a therapy in routine clinical practice. Such assessments typically better reflect the patient population in which the intervention is being used, which is often much less homogeneous than the patient population involved in a clinical trial. Similarly, factors such as patient compliance, concomitant therapy use, and stage of disease at treatment initiation, which may significantly influence outcomes, may differ in routine clinical practice compared with a controlled clinical trial setting. For example, a review concluded that fingolimod is generally initiated in routine clinical practice in patients with MS at a later stage of disease compared with those enrolled in the pivotal clinical trials [15].

Various real-world studies have investigated the comparative effectiveness of the established injectable DMTs (IFNβ and GA) and fingolimod [16,17,18]. However, to date, no studies have reported on the effectiveness of DMF or teriflunomide in a real-world setting. The objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of available oral and injectable DMTs in a real-world setting based on US claims data.

Methods

Data Source

This retrospective claims analysis was based on data from the Truven MarketScan Commercial Claims Databases. Claims data from 2012 to 2014 were analyzed to compare the effectiveness of the following DMTs for the management of MS: DMF, IFNβ, GA, teriflunomide, and fingolimod. The Truven MarketScan Commercial Claims Databases contain the de-identified administrative claims and eligibility records of over 120 million commercially insured individuals from all US regions and include three main components: (1) claims for medical services provided in both the inpatient and outpatient settings with the associated diagnosis, service dates, place of service, procedures performed, and patient- and plan-paid amounts; (2) pharmacy claims with the associated dispense date, National Drug Code, dose, days of supply, and patient- and plan-paid amounts; (3) patient demographic information including year of birth, sex, and region of residence. Information on the diagnostic criteria used for MS diagnosis, severity and duration of MS, rate of progression, results of laboratory or imaging tests, or measurements of neurologic or MS-related disability, such as the expanded disability status scale (EDSS), is not routinely captured in claims data.

All patient information was anonymized, and patient confidentiality was maintained through compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations. The analysis presented is based on previously collected data and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Patient Identification

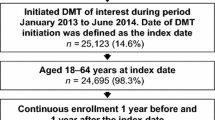

Adult patients with MS were identified as individuals having at least one hospitalization with an associated diagnosis suggesting MS [International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM): diagnosis code 340] or two outpatient visits with the same ICD-9-CM diagnosis code dated at least 30 days apart. Patients who initiated one of the DMTs of interest (DMF, IFNβ, GA, teriflunomide, or fingolimod) during the 2013 calendar year were identified; initiation was defined as having no claims for the same DMT in the prior year. Patients switching from another DMT were included in the analysis. Patients initiating natalizumab or alemtuzumab during the study period were not included in the analysis because the focus of this study was on oral and injectable DMTs. Eligible DMT initiators were assigned to corresponding DMT cohorts according to their initiated DMT; patients were not randomized to treatment cohorts. The date of DMT initiation was defined as the index date. Patients aged between 18 and 64 years at the index date were included in the analysis. To ensure complete data were available for the assessment of baseline characteristics and study outcomes, selected patients were required to have continuous enrollment in the Truven MarketScan Commercial Claims Databases at least 1 year before and 1 year after the index date (Fig. 1).

Study Measures

Patient demographics included age at index date, sex, and region of residence. Baseline clinical characteristics were assessed based on medical and pharmacy claims dated within 1 year before the index date. Chronic disease burden was measured using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a composite score calculated based on the presence of 22 chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, peptic ulcer, liver disease, cancer), with each condition being assigned a score of 1, 2, 3, or 6 [19]. CCI was originally designed to predict 10-year mortality and has been widely used to assess chronic disease burden in large retrospective studies. The proportion of patients experiencing MS-related symptoms within 1 year prior to the index date was assessed. The selection of symptoms as being MS-related was based on a published study [20] and clinical input from the research investigators.

The ARRs 1 year before and 1 year after the index date were calculated as the number of relapse episodes that a patient had during a year. Relapse episodes were identified based on a published claims-based algorithm [21, 22]. In our analysis, a patient was considered to have experienced a moderate-to-severe relapse if they were hospitalized with a primary diagnosis suggesting MS or had an outpatient visit with at least one associated diagnosis suggesting MS together with evidence of receiving high-dose oral steroid (≥500 mg/day prednisolone or equivalent), intravenous corticosteroid, corticotropin (i.e., adrenocorticotropic hormone), or plasma exchange within 30 days of the outpatient visit. As patients may have had multiple clinical encounters during one relapse, all qualified hospitalizations or outpatient visits that occurred within 30 days of each other were considered as one relapse episode.

To support subgroup analyses, adherence to the index DMT was assessed based on the pharmacy claims dated within 1 year following the index date via the medication possession ratio (MPR). MPR is estimated as the total number of days of supply of all fills of the index DMT within the refill interval, divided by the number of days in the refill interval. The MPR was calculated among patients with at least two prescription fills, for the interval between the first and last fill, during the 1-year follow-up period (referred to as the refill interval). High MPR represents good patient adherence to DMT. Values for MPR were capped at 1.

Statistical Analysis

Distribution of baseline characteristics and outcomes was assessed for each DMT cohort. Percentages were presented for categorical measures and mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous measures. Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to test whether changes in ARR before and after DMT initiation were significantly different from zero. Study measures were compared between each of the DMT cohorts and the DMF cohort, which was used as the reference group. Student t tests (continuous variables) and chi-squared tests (categorical variables) were used to detect significant differences between the DMF cohort and the other cohorts.

Poisson and negative binomial regression models were estimated to control for differences in patient populations between the different DMT cohorts while comparing the ARR for 1 year after the index date between DMT cohorts. The following potential confounders were included in the models: age categories (18–30, 31–40, 41–50, and 51–64 years), sex, region of residence, number of relapses experienced in 1 year before the index date (0, 1, 2, and ≥3), use of any other DMT during the 1 year prior to the index date, CCI score, and the presence of individual MS-related symptoms. As the largest cohort included in the study, the DMF cohort was assigned as the reference group. The adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for relapse relative to the DMF cohort are presented with the associated 95% confidence interval (CI).

Subgroup analyses were conducted to analyze ARR in patients who were adherent to treatment (defined as those having an MPR of ≥0.8, ≥0.7, or ≥0.6) and patients aged younger than 40 years. Sensitivity analyses comprised logistic regression (to assess binary outcomes) and using 7 days as the cut-off for consecutive clinical encounters, which were defined as a single relapse (compared with 30 days in the primary analysis).

Results

A total of 6372 patients with MS meeting the inclusion criteria were identified in the Truven MarketScan Commercial Claims Databases (2012–2014). Of this cohort, 52.6% of patients initiated DMF, 13.9% initiated IFNβ, 16.6% initiated GA, 7.8% initiated teriflunomide, and 9.1% initiated fingolimod. Mean (SD) ages for the cohorts ranged from 43.5 (10.4) years for GA to 49.6 (8.9) years for teriflunomide (Table 1). Between 76% and 80% of patients were female, and the CCI scores ranged from 0.42 (0.91) for fingolimod to 0.76 (1.33) for GA. Approximately 85% of patients in the GA and IFNβ cohorts had not received DMT in the year prior to the index date compared with only approximately one-third of patients in the other three cohorts. Differences in the frequency of the MS-related symptoms identified were seen across cohorts (Table 1).

Unadjusted ARR for the year prior to the index date ranged from 0.31 for GA to 0.44 for fingolimod and ranged from 0.30 for DMF to 0.35 for teriflunomide for the year after the index date (Fig. 2). Significant reductions in unadjusted ARR were observed in the DMF [0.129 (30.4%) reduction, P < 0.0001] and fingolimod [0.135 (30.5%) reduction, P < 0.0001] cohorts in the year after initiating therapy. The greatest increases in the proportion of patients experiencing no relapses in the year after DMT initiation were observed in the DMF and fingolimod cohorts (+8.1% and +11.6%, respectively) compared with +5.9%, +2.9%, and +6.2% in the IFNβ, glatiramer acetate, and teriflunomide cohorts, respectively. Reductions in the proportion of patients experiencing two or more relapses over a 1-year period were observed in the DMF and fingolimod cohorts [–3.8% and –1.2%, respectively, compared with increases in the IFNβ, glatiramer acetate, and teriflunomide cohorts (+2.4%, +4.1%, and +1.2%, respectively)]. Data on the proportion of patients experiencing relapses in the year before and the year after DMT initiation are reported in Table S1 in the supplementary material.

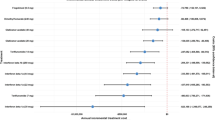

After Poisson regression to adjust for differences in baseline patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and prior DMT exposure, the adjusted IRR for relapse in the first year after initiating therapy was compared for each therapy relative to the DMF cohort. The adjusted IRR (95% CI) was 1.03 (0.88–1.21) for fingolimod indicating no significant difference in effectiveness between fingolimod and DMF. After adjusting for confounders, the adjusted IRRs compared with DMF were 1.27 (1.10–1.46) for IFNβ, 1.34 (1.17–1.53) for GA, and 1.23 (1.05–1.45) for teriflunomide, indicating a statistically significant effectiveness advantage for DMF over these DMTs (Fig. 3). The number of relapses in the year prior to DMT initiation (P < 0.0001) and the presence of fatigue or malaise (P = 0.0011) are also significant predictors for ARR after DMT initiation. Full regression analysis results are reported in Table S2 in the supplementary material.

Adjusted IRR (95% CI) of ARR for 1 year after initiation of DMT for the interferon beta, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, and fingolimod cohorts relative to the DMF cohort. An IRR <1.0 means that the ARR of the comparator DMT cohort is lower than the DMF cohort, whereas an IRR >1.0 means that the ARR of the comparator DMT cohort is higher than the DMF cohort. For example, an IRR for interferon beta versus DMF of 1.27 means that the ARR in the interferon beta cohort is 27% higher than that of the DMF cohort after adjusting for baseline differences. ARR annualized relapse rate, CI confidence interval, DMF dimethyl fumarate, DMT disease-modifying therapy, IRR incidence rate ratio

Adjusted IRRs for relapse in the first year after initiating therapy were similar after negative binomial regression. Adjusted IRRs (95% CI) were 1.02 (0.85–1.23) for fingolimod, 1.28 (1.08–1.51) for IFNβ, 1.32 (1.13–1.55) for GA, and 1.21 (1.00–1.47) for teriflunomide. The number of relapses in the year prior to DMT initiation (P < 0.0001) and the presence of fatigue or malaise (P = 0.0037) were both significant predictors for ARR after DMT initiation. Full regression analysis results are reported in Table S3 in the supplementary material.

Results for subgroup analyses were consistent with those for the overall population. The Poisson regression adjusted IRRs for patients who were adherent to DMT treatment (defined as having an MPR of ≥0.8) demonstrated that DMF provided a significantly lower ARR in the post-index period than IFNβ, GA, and teriflunomide (P < 0.05 in all pair-wise comparisons; Fig. 4). Further subgroup analyses for adherent patients (defined as an MPR of ≥0.6 or ≥0.7) confirmed the significantly lower ARR in the DMF cohort compared with the IFNβ, GA, and teriflunomide cohorts (Table S4 in the supplementary material). Analysis of the subgroup of patients aged younger than 40 years demonstrated that the ARR in the post-index period was significantly lower in the DMF cohort than in the IFNβ and GA cohorts (P < 0.05; Table S4 in the supplementary material). Results from sensitivity analyses using logistic regression and alternative criteria for relapse were all consistent with the findings for the primary analysis (data not shown).

Adjusted IRR (95% CI) of relapse in the first year after initiation of interferon beta, glatiramer acetate, teriflunomide, and fingolimod relative to DMF for patients adherent to therapy (defined as an MPR of ≥0.8). An IRR <1.0 means that the ARR of the comparator DMT cohort is lower than that of the DMF cohort, whereas an IRR >1.0 means that the ARR of the comparator DMT cohort is higher than that of the DMF cohort. For example, an IRR for interferon beta versus DMF of 1.40 means that the ARR in the interferon beta cohort is 40% higher than that of the DMF cohort after adjusting for baseline differences. ARR annualized relapse rate, CI confidence interval, DMF dimethyl fumarate, DMT disease-modifying therapy, IRR incidence rate ratio, MPR medication possession rate

Discussion

This study, the first to report real-world comparative effectiveness data across all available oral and injectable DMTs, indicates that DMF and fingolimod have similar effectiveness for relapse prevention in patients with MS and demonstrate superior effectiveness to IFNβ, GA, and teriflunomide in routine clinical practice. This finding was consistent across all subgroup and sensitivity analyses indicating that, irrespective of the patient subgroup assessed, DMF and fingolimod provide substantial and significant reductions in ARR that are superior to those provided by IFNβ, GA, and teriflunomide.

The findings in the present study suggest an effect of the pre-treatment relapse rate on the on-treatment relapse rate. ARR in the pre-index period was highest in the DMF and fingolimod cohorts, with the largest ARR reductions observed in the same cohorts. The findings also suggest an effect of prior therapy on post-DMT initiation relapse rates; approximately 85% of patients initiating IFNβ or GA had not received treatment in the previous year compared with 31–36% of patients receiving DMF, fingolimod, or teriflunomide. Interpretation of these results should therefore be conducted in the context of the differences between cohorts as determinants of pre-index ARR, such as the level of disability, MS phenotype, and time since first MS diagnosis. As claims databases do not include this information, the current analysis is unable to control for these factors. However, these data derived from routine clinical practice are consistent with those from a mixed treatment comparison of the comparative efficacy of DMF, IFNβ, GA, teriflunomide, and fingolimod based on clinical trial data [13]. Our results now extend these findings to the real-world setting and confirm that, in routine clinical practice, DMF is likely to provide superior outcomes for patients compared with teriflunomide, GA, and IFNβ, as well as the benefits of oral therapy, in terms of patient convenience, compared with the latter two parenterally administered DMTs. The use of long-term, self-administered injections is burdensome to some patients, especially those with a needle phobia, and is associated with injection-related adverse events [23]. Inconvenience, needle phobia, and injection-site reactions, among others, are factors recognized to negatively affect adherence to therapy [23]. By contrast, the use of oral therapies overcomes patient concerns relating to needle phobia and injection-site reactions and offers a convenient method of administration [23].

The similar effectiveness data for DMF and fingolimod in our analysis are consistent with prior analyses based on the clinical trial data, indicating that both DMTs provide an appropriate choice of therapy for patients with RRMS. Moreover, the findings in the present study are consistent with an analysis of 775 propensity-matched patients with MS receiving either DMF (n = 458) or fingolimod (n = 317) in routine clinical practice in the USA [24]. In this analysis, there was no significant difference in ARR, overall brain magnetic resonance imaging activity, and discontinuations at 1 year of therapy for patients receiving DMF or fingolimod [24].

Results reported in the present study were robust, irrespective of the subgroup or sensitivity analysis performed, and consistent with the large number of patients included in the analysis. Neither age (<40 years) nor adherence to therapy (MPR of ≥0.8, ≥0.7, or ≥0.6) substantially impacted on the conclusions from the primary analysis. The minimal influence of DMT adherence on the relapse rates is important given the potential role of adherence in DMT effectiveness. Our findings indicate that differences in DMT effectiveness remain robust even with moderate decreases in DMT adherence. Sensitivity analyses also had no relevant impact on the findings from the primary analysis, irrespective of changes to the method of analysis used (negative binomial regression or logistics regression) and to the time frame considered as a single relapse event. Together, the subgroup and sensitivity analyses confirm our findings that DMF provides substantial and significant reductions in ARR that are comparable with those provided by fingolimod and superior to those provided by IFNβ, GA, and teriflunomide.

As clinical evidence of MS relapse is not included in claims data, relapses were identified based on a validated algorithm derived from the ICD-9-CM diagnosis code and details of medications dispensed. This algorithm has been used in previous studies to determine relapse rates in patients with RRMS based on claims data and allows the identification of moderate-to-severe relapses that result in a clinical encounter. However, patients with a mild relapse may not seek an appointment with a physician; thus, mild relapses may be difficult to identify.

Validation of the algorithm by Chastek and colleagues was achieved by a comparison with medical charts and clinician review, resulting in the classification of 67.3% of patients with relapses (positive predictive value) and 70.0% of patients without relapses (negative predictive value) in a sample of 300 patients [22]. Although this approach may underestimate the overall relapse incidence, this effect is anticipated to be uniform across all comparisons. We also assessed algorithm robustness and sensitivity by varying input parameters (including using the originally published algorithm), considering outpatient visits involving plasma exchange and high-dose oral steroid use as identifying a relapse event and considering clinical encounters occurring within 7 days (as opposed to 30 days) of each other as a single event. ARRs derived by all variations of the algorithm were in good agreement, differing by less than 0.1 (data not shown). Furthermore, the ARRs reported here are in the same range as those reported from clinical trials and are consistent with the ARRs reported in studies of real-world data [17, 25]. Our study, therefore, provides further confirmation of the validity of this approach for determining ARR from claims data.

The present study is subject to a number of the limitations associated with retrospective studies utilizing administrative claims data. First, data are collected for the purposes of billing and monitoring the quality of care, not for assessing treatment effectiveness, and are subject to coding errors, although these are anticipated to occur at random. Second, the data do not contain information on the diagnostic criteria used, severity and duration of MS, rate of progression, or results of laboratory or imaging tests; differences in neurologic or MS-related disability were not measured or accounted for as this information is not captured in claims data. These data would allow the analysis to control for differences in cohort clinical characteristics. Future studies are needed to develop and validate an algorithm to control for these confounders. Finally, MS relapses were identified from administrative claims and do not necessarily correspond to events as identified in clinical trials (e.g., a relapse can be defined as new or recurrent neurologic symptoms lasting for ≥24 h and accompanied by new objective neurologic findings) [26]. However, the influence of potential misclassification is not expected to bias specific DMTs.

In this study, patients were not randomized to treatment, and Poisson and negative binomial regression was applied to account for differences in some of the clinical and demographic variables observed in the data set. Matching patients, through propensity score matching, provides an alternative approach to controlling for these variables, but would not have eliminated any potential confounding for the matched variables [27]. The use of regression analysis in this study maintains statistical precision by allowing the use of all patient information rather than discarding information for unmatched patients [28]. Importantly, as discussed, the results of this study were comparable with those reported for DMF and fingolimod in propensity-matched patients with MS [24]. However, further studies are needed to confirm whether the clinical and demographic variables not captured in claims data influence relapse rates in patients with MS receiving an oral or injectable DMT.

Conclusion

This study provides the first real-world evidence comparing the effectiveness of oral and injectable DMTs for the management of MS in routine clinical practice. Our results indicate that there are significant differences in the effectiveness of the different DMTs in patients with MS. These data should assist in treatment decisions regarding the choice of DMT and enable clinicians to consider both real-world effectiveness and route of administration in consultations with their patients. Additional data are warranted to provide evidence for the long-term effectiveness of the newer oral therapies, including the impact of these therapies on disability progression. Such data should assist clinicians in determining the role of the growing number of treatment options in the management of RRMS to achieve the maximum therapeutic benefit for patients.

References

Goldenberg MM. Multiple sclerosis review. P T. 2012;37(3):175–84.

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372(9648):1502–17.

Kantarci OH, Pirko I, Rodriguez M. Novel immunomodulatory approaches for the management of multiple sclerosis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;95(1):32–44.

Campbell JD, Ghushchyan V, Brett McQueen R, et al. Burden of multiple sclerosis on direct, indirect costs and quality of life: National US estimates. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3(2):227–36.

Browne P, Chandraratna D, Angood C, et al. Atlas of multiple sclerosis 2013: a growing global problem with widespread inequity. Neurology. 2014;83(1):1022–4.

Hunter SF. Overview and diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(6 Suppl):s141–50.

McKay KA, Kwan V, Duggan T, Tremlett H. Risk factors associated with the onset of relapsing-remitting and primary progressive multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:817238.

Cohen BA, Coyle PK, Leist T, Oleen-Burkey MA, Schwartz M, Zwibel H. Therapy optimization in multiple sclerosis: a cohort study of therapy adherence and risk of relapse. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2015;4(1):75–82.

Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):402–15.

Vermersch P, Czlonkowska A, Grimaldi LM, et al. Teriflunomide versus subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Mult Scler. 2014;20(6):705–16.

Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1087–97.

Oh J, O’Connor PW. Established disease-modifying treatments in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28(3):220–9.

Hutchinson M, Fox RJ, Havrdova E, et al. Efficacy and safety of BG-12 (dimethyl fumarate) and other disease-modifying therapies for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and mixed treatment comparison. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(4):613–27.

Tramacere I, Del Giovane C, Salanti G, D’Amico R, Filippini G. Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; 9:CD011381.

Fonseca J. Fingolimod real world experience: efficacy and safety in clinical practice. Neurosci J. 2015;2015:389360.

Frisell T, Forsberg L, Nordin N, et al. Comparative analysis of first-year fingolimod and natalizumab drug discontinuation among Swedish patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2016;22(1):85–93.

Kalincik T, Jokubaitis V, Izquierdo G, et al. Comparative effectiveness of glatiramer acetate and interferon beta formulations in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21(9):1159–71.

Bergvall N, Makin C, Lahoz R, et al. Comparative effectiveness of fingolimod versus interferons or glatiramer acetate for relapse rates in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective US claims database analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(12):1647–56.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Curkendall SM, Wang C, Johnson BH, et al. Potential health care cost savings associated with early treatment of multiple sclerosis using disease-modifying therapy. Clin Ther. 2011;33(7):914–25.

Ollendorf DA, Jilinskaia E, Oleen-Burkey M. Clinical and economic impact of glatiramer acetate versus beta interferon therapy among patients with multiple sclerosis in a managed care population. J Manag Care Pharm. 2002;8(6):469–76.

Chastek BJ, Oleen-Burkey M, Lopez-Bresnahan MV. Medical chart validation of an algorithm for identifying multiple sclerosis relapse in healthcare claims. J Med Econ. 2010;13(4):618–25.

Patti F. Optimizing the benefit of multiple sclerosis therapy: the importance of treatment adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2010;4:1–9.

Hersh CM, Cohn S, Hara-Cleaver RA. Comparative efficacy and adherence of dimethyl fumarate and fingolimod in clinical practice at 12-month follow-up. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;10:44–52.

Bergvall N, Makin C, Lahoz R, et al. Relapse rates in patients with multiple sclerosis switching from interferon to fingolimod or glatiramer acetate: a US claims database study. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88472.

Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(12):1098–107.

Pearce N. Analysis of matched case-control studies. BMJ. 2016;352:i969.

Klein JP, Rizzo JD, Zhang MJ, Keiding N. Statistical methods for the analysis and presentation of the results of bone marrow transplants. Part 2: regression modeling. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28(11):1001–11.

Acknowledgements

This study and the article processing charges were funded by Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Writing and editorial support for manuscript preparation was provided by Dr. Nick Leach of OPEN Access Consulting, UK. Funding for editorial support was provided by Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

Aaron Boster has received research funding from Genentech, Actellion, and Mallenkropt and has received consulting and speaking honoraria from Genzyme, Novartis, Teva, Biogen, and Medtronic. Jacqueline Nicholas has received research funding from Genzyme, Novartis, Teva, Biogen, and Alexion and has received consulting and speaking honoraria from Genzyme, Novartis, Teva, Biogen, and Medtronic. Ning Wu was an employee of Biogen at the time of the study. Wei-Shi Yeh was an employee of Biogen at the time of the study. Monica Fay is an employee of, and holds stock and/or stock options in, Biogen. Michael Edwards is an employee of, and holds stock and/or stock options in, Biogen. Ming-Yi Huang is an employee of, and holds stock and/or stock options in, Biogen. Andrew Lee is an employee of, and holds stock and/or stock options in, Biogen.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously collected data and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The data sets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they were licensed with restrictions from a third party source.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Boster, A., Nicholas, J., Wu, N. et al. Comparative Effectiveness Research of Disease-Modifying Therapies for the Management of Multiple Sclerosis: Analysis of a Large Health Insurance Claims Database. Neurol Ther 6, 91–102 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-017-0064-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-017-0064-x