Abstract

Introduction

Guidelines recommend that patients with acute venous thromboembolism (VTE) represented by low-risk deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) receive initial treatment at home versus at the hospital, but a large percentage of these patients are not managed at home. This study assessed the effectiveness of a quality intervention on provider knowledge and confidence in evaluating outpatient treatment for patients with VTE in the emergency department (ED).

Methods

A pilot program to overcome obstacles to outpatient VTE treatment in appropriate patients was initiated at Baylor Scott & White Health Temple ED. Subsequently, a formalized quality intervention with a targeted educational program was developed and delivered to ED providers. Provider surveys were administered pre- and post-quality intervention in order to assess clinical knowledge, confidence levels, and perceived barriers. Patient discharge information was extracted from electronic health records.

Results

Twenty-five ED providers completed the pre- and post-surveys; 690 and 356 patients with VTE were included in the pre- and post-pilot and pre- and post-quality intervention periods, respectively. Many ED providers reported that a major barrier to discharging patients to outpatient care was the lack of available and adequate patient follow-up appointments. Notably, after the quality intervention, an increase in provider clinical knowledge and confidence scores was observed. Discharge rates for patients with VTE increased from 25.6% to 27.5% after the pilot intervention and increased from 28.5% to 29.9% after the quality intervention, but these differences were not statistically significant. Despite instantaneous uptick in discharge rates after the interventions, there was not a long-lasting effect.

Conclusion

Although the quality intervention led to improvements in provider clinical knowledge and confidence and identified barriers to discharging patients with VTE, discharge rates remained stable, underscoring the need for additional endeavors.

Plain Language Summary

When patients develop blood clots in their veins or have blood clots travel to their lungs, they may seek treatment at the hospital emergency department. As a best practice, most people can treat blood clots with medicines at home; however, many patients are treated at the hospital. This study looked at how an education program for doctors in the hospital could help more patients be treated at home. The education program improved doctors’ knowledge and confidence when evaluating patients with blood clots who could be treated at home. However, this study found that the number of patients treated at home was the same before and after the doctors participated in the education program. Two major problems that prevented patients from being treated at home were not having follow-up appointments readily available and patients taking their medicine as needed. More and different types of programs may help doctors understand the best ways to treat patients with blood clots in the emergency department.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Clinical practice guidelines recommend that patients with low-risk acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and low-risk pulmonary embolism (PE) receive initial treatment at home rather than in the hospital; however, there is a large gap between the numbers of patients actually managed at home and those who could possibly have been managed at home but were admitted into the hospital. |

Barriers to outpatient management of venous thromboembolism (VTE) include lack of provider knowledge, insufficient dedicated follow-up, poor provider-patient and provider-provider communication, and the high cost of medications. |

This study assessed if provider knowledge improved and discharge rates of patients with VTE from the emergency department increased after physician education. |

What was learned from the study? |

While this provider education initiative led to improvements in both clinical knowledge scores and confidence scores and identified that a major barrier to discharging patients with VTE to outpatient care was the lack of adequate follow-up appointments, the study did not result in an expected increase in discharge rates. |

Sustained practice changes are needed to ensure that eligible patients with VTE receive appropriate outpatient care post-discharge by providing tools to address medication and continuity barriers as well as periodic education, incorporation of decision support tools, and regular assessments of the performance of the clinical pathway. |

Introduction

As many as 900,000 people are estimated to be affected by venous thromboembolism (VTE) each year in the USA [1]. Clinical practice guidelines such as those from the American College of Chest Physicians have endorsed the recommendation that patients with low-risk acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and low-risk pulmonary embolism (PE) receive initial treatment at home rather than in the hospital since 2012 and 2016, respectively [2, 3]. Although these guidelines have been circulated for a decade, there is a large gap between those patients actually managed at home and those who are admitted into the hospital. In 2020, approximately 266,000 patients with acute DVT or PE were admitted for an inpatient hospital stay, with costs totaling over US$3.6 billion [4]. In addition, a real-world pragmatic effectiveness trial conducted in 33 emergency departments (EDs) in the USA found that only 10% of patients with PE and 18% of patients with DVT were managed at home [5].

To promote the systematic adoption of guidelines-based practices into routine care, interventions must not only focus on the patient level but also on the provider and organizational levels. The literature reports barriers among healthcare providers to prescribing direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for outpatient management of VTE, including lack of knowledge, insufficient dedicated follow-up, poor provider-patient and provider-provider communication, and high cost of medications [6, 7]. To address these barriers, provider education may be an integral step in improving guidelines-concordant management of VTE in the outpatient setting. In a study reported by Falconieri et al. [8], a brief educational presentation was delivered during ED grand rounds, resulting in an improvement in assessments made before and after the training, including a better ability to correctly identify recommended laboratory values and social criteria for admission.

Healthcare systems have the potential to alleviate the economic and clinical burden of VTE by improving adherence to guidelines’ recommendation to discharge low-risk patients and manage them in the outpatient setting. Ensuring access to appropriate anticoagulant therapy and maintaining continuity of care may mitigate provider hesitation and consequently increase the percentage of patients treated at home.

This project assessed the impact of barriers previously reported by healthcare providers on the outpatient management of VTE among a contemporary cohort of ED physicians. Furthermore, it evaluated the effectiveness of a quality intervention in enhancing outpatient VTE practices within the same cohort of providers. We tested the following hypotheses: (1) there was no difference in clinical knowledge scores between pre- and post-quality intervention to identify low-risk patients with VTE suitable for outpatient management; (2) there was no difference in the overall confidence scores between pre- and post-quality intervention regarding the evaluation of factors determining eligibility of patients with VTE in the ED for outpatient treatment; and (3) there was no difference in the proportion of patients with VTE discharged from the ED pre- and post-intervention (pilot and quality interventions). We also evaluated the provider-reported impact of barriers and social determinants of health (SDOH) factors on the decision to discharge a patient from the ED for outpatient management of VTE.

Methods

Providers and Patients

Providers had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) employee at Baylor Scott & White Health (BSWH) at the time of the intervention; (2) working in the the ED of the Baylor Scott & White Temple hospital; (3) holding a position of resident, attending, or staff physician; and (4) providing informed consent.

To be eligible for inclusion in the electronic health record (EHR) analysis, aggregate de-identified patient-level data must have met the following criteria: (1) patient was evaluated at the ED, and (2) had a primary diagnosis of new-onset VTE as defined by International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes for acute pulmonary embolism (I26.0x, I26.9x), acute lower extremity thrombosis (I80.1x, I80.2x, I80.3x, I80.8x, I80.9x, I82.4x), acute upper extremity thrombosis (I82.60x, I82.62x, I82.A1x, I82.B1x), or acute embolism of other specified veins (I82.890, I82.90). These ICD-10-CM codes have been used in prior publications [9,10,11] and were reviewed by a BSWH clinician. Codes related to superficial thrombosis, chronic thrombosis, and complex diagnoses such as Budd-Chiari syndrome, inferior vena cava thrombus, renal vein thrombus, and intrathoracic thrombus were excluded.

This study was eligible for expedited review as it posed minimal risk to study participants, and it was approved by the BSWH institutional review board (IRB ID: 023-032). All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study. Consent documents and recruitment materials were approved by Pfizer and by the institutional review board/independent ethics committee before use. This study was conducted at the Baylor Scott & White Temple hospital. The evaluation was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value, and rigor and follow generally accepted research practices described in Good Practices for Outcomes Research issued by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Study Design

Study Timeline

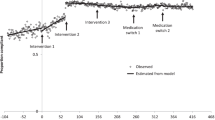

The pilot program to discharge appropriate patients with acute VTE from the ED with outpatient treatment was initiated on 14 October 2021. For patients considered eligible for discharge, the pilot program consisted of a complimentary 30-day supply of either rivaroxaban or apixaban, a scheduled follow-up appointment within 2 weeks of discharge, and an informal educational program for ED providers. A pre-pilot period from 14 December 2020 to 14 October 2021 (10 months) and a post-pilot period from 15 October 2021 to 14 August 2022 (10 months) were used for the EHR analysis portion of the study (Fig. 1).

Recognizing the favorable prospects of the pilot program, it was determined that the program would be expanded by formally constructing a comprehensive quality intervention. This intervention comprised a robust educational session for ED providers; this quality intervention took place on 16 January 2023. In addition, there were surveys of participating providers to evaluate the impact of the educational session, and a patient-centric infographic focusing on VTE care that took place on 26 January 2023. A pre-quality intervention period from 21 August 2022, to 26 January 2023 (5 months, 5 days) and a post–quality intervention period from 27 January 2023 to 1 July 2023 (5 months, 5 days) were used for the EHR analysis portion of the study (Fig. 1).

Quality Intervention Format

The quality intervention comprised of an approximate 10-min pre-provider survey of 56 questions, followed by a 30-min academic presentation, and then an approximately 10-min post-provider survey of 46 questions. The academic presentation reviewed the guidelines for anticoagulant therapy for VTE, a clinical decision framework to guide the outpatient treatment of ED patients diagnosed with acute VTE (DVT and PE), and the resources available. One of the available resources specifically developed for this initiative included a patient-centric infographic, which physicians could utilize when discharging patients from the ED (Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM] Fig. S1). The presentation was delivered by a board-certified hematologist/oncologist with extensive experience in providing care to patients with VTE and over 20 years of experience in educating medical students, physicians, and nursing staff.

Pre- and Post-Quality Intervention-Provider Surveys

Participant surveys were conducted before and after the provider quality intervention education session and comprised four sections: demographics, clinical knowledge, current practice/recall, and SDOH. Respondents’ questions on demographics included provider type, years of experience, and whether they had received the pilot education on 14 October 2021.

Our primary outcomes included providers’ knowledge of and confidence in evaluating factors that determine whether a patient with VTE in the ED is eligible for outpatient treatment. Clinical knowledge was assessed using 17 hypothetical patient scenarios. Each response was categorized as either correct or incorrect, with 1 point given for each correct answer and zero points for each incorrect answer. Respondents who selected “I don’t know” were considered to have answered incorrectly. A final score out of 17 points was calculated for each provider. Quality intervention survey participants rated their overall confidence in evaluating factors that determined the eligibility of a patient with VTE in the ED for outpatient treatment using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = ‘not confident’ to 4 = ‘completely confident’). In addition, participants rated their confidence in assessing clinical criteria (e.g., comorbidities, risk of bleeding, etc.) for patients with DVT and/or PE, selecting an appropriate DOAC, and addressing social health needs for patients with VTE using the same 5-point Likert scale. For questions regarding DVT specifically, the total score ranged from 0 to 20. Each respondent’s score was reported as a percentage of the total possible 20 points and grouped into categories: ≤ 20%, not confident; > 20% to ≤ 40%, slightly confident; > 40 to ≤ 60%, somewhat confident; > 60 and ≤ 80%, fairly confident; and > 80 to ≤ 100%, completely confident. For questions regarding PE specifically, the total score ranged from 0 to 16. Each respondent’s score was reported as a percentage of the total possible 16 points and grouped into the same categories as DVT. Choosing an appropriate DOAC and addressing social health needs for a patient with VTE were each assessed with a single question using a total score ranging from 0 to 4.

Secondary outcomes included assessing the impact of provider-reported barriers and patient SDOH characteristics on the decision to discharge a patient with VTE from the ED, rated on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = not a barrier/not difficult at all to 2 = significant barrier/very difficult). The section on provider-reported barriers included nine barriers, with possible total scores ranging from 0 to 18. The SDOH section included six factors, with possible total scores ranging from 0 to 12. Another secondary outcome was the proportion of patients with VTE discharged from the ED before and after the pilot and quality interventions. Patient admission and discharge information were obtained from the local EHR system, “Epic.”

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics including means with standard deviation (SD) or medians with first and third quartiles (Q1-Q3), were calculated for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were calculated for all categorical variables. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare providers’ survey responses (i.e., clinical knowledge score, confidence score, and SDOH impact scores) pre-quality and post-quality intervention. A two-proportion z-test was used to compare the differences in the overall proportion of patients with VTE discharged from the Temple ED pre- and post-intervention (pilot and quality intervention). In addition, interrupted time series (ITS) analyses were performed to explore the temporal changes in the ED patient discharge rate taken at a regularly spaced interval (e.g., month) and, more specifically, the changes at the time when an intervention (e.g., the pilot and quality intervention) was implemented.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), R statistical software (version 2023.06.2; R Foundation, Vienna, Austria), and Stata/BE (version 18.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA), with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. No imputation for missing values was performed.

Results

Survey Analysis: Clinical Knowledge and Confidence Scores

A total of 25 providers, consisting of 21 residents and four attending physicians, completed the pre- and post-quality intervention surveys, with 60% being VTE education naive (ESM Table S1).

Relative to the post-quality intervention, there was a statistically significant increase in providers’ median clinical knowledge scores compared with pre-quality intervention (range 0–20; pre-intervention, 13.0 [Q1–Q3, 11.0–14.0]; post-quality intervention score, 15.0 [Q1–Q3 14.0–16.0]; P < 0.0001). There were also statistically significant increases in aggregate median confidence scores for each category compared with pre-quality intervention scores. These included assessing clinical criteria used to determine outpatient management, choosing an appropriate DOAC, addressing social health needs, and evaluating factors that determine if a patient with VTE in the ED is eligible for outpatient treatment (Table 1).

When providers were asked about their confidence in assessing comorbidities requiring surgical or medical admission for patients with DVT, the percentage of respondents reporting “fairly confident” or “completely confident” increased from 72% in the pre-quality intervention survey to 87% in the post-quality intervention survey (Fig. 2a). All respondents either maintained their initial confidence level or reported an increase in confidence post-quality intervention (Fig. 2b). No respondents, either before or after the quality intervention, reported feeling not confident. A similar increase was observed pre- to post-quality intervention regarding provider confidence in assessing comorbidities necessitating surgical or medical admission for patients with PE (ESM Fig. S2).

The percentage of respondents reporting “fairly confident” or “completely confident” in addressing social health needs related to outpatient management of VTE increased from 20% in the pre-quality intervention survey to 61% in the post-quality intervention survey (Fig. 3a). Most respondents either maintained their initial level of confidence or reported an increase in their confidence in the post-quality intervention survey compared with the pre-quality intervention survey (Fig. 3b).

When overall provider confidence was assessed in evaluating factors to determine if a patient with VTE in the ED is eligible for outpatient treatment, the percentage of respondents reporting “fairly confident” or “completely confident” increased from 20% in the pre-quality intervention survey to a pronounced 74% in the post-quality intervention survey (Fig. 4a). All respondents either maintained their initial level of confidence or reported an increase in their confidence in the post-quality intervention survey compared with the pre-quality intervention survey (Fig. 4b).

Assessing provider confidence: provider’s overall confidence in evaluating factors that determine if a patient with VTE in the emergency department is eligible for outpatient treatment. a Proportion of providers by response and b progression of responses pre- to post-quality intervention. VTE Venous thromboembolism

Survey Analysis: Barriers and Social Determinants of Health

When evaluating the impact of barriers and SDOH factors on providers' decisions to discharge patients with VTE from the ED for outpatient management, pre- and post-survey findings revealed that a significant number of providers viewed the lack of a dedicated post-discharge appointment with a clinician as a substantial barrier. Of the 25 providers surveyed pre-quality intervention, 24% considered lack of an appointment somewhat of a barrier, while 72% regarded it as a significant barrier (Fig. 5a). Post-quality intervention, of the 23 respondents, 43% identified lack of an appointment as somewhat of a barrier, and 48% still considered it a significant barrier; these two categories accounted for 91% of all providers, in both pre- and post-quality intervention surveys. Most providers maintained their perception of the lack of an appointment barrier's level pre- and post-quality intervention, with a few transitioning from the significant barrier category to somewhat of a barrier, and one provider shifted from somewhat of a barrier to deeming it a significant barrier (Fig. 5b). Additional persistent barriers to discharging patients noted by the providers even after the post-quality intervention included bleeding concerns, patient adherence to VTE medications, and lack of patient education regarding treatment of their condition (ESM Table S2). The SDOH factors that providers identified as very difficult for patients were socioeconomic barriers, such as low income and unemployment (76%), housing instability (67%), and low health literacy (64%) (ESM Table S3).

EHR Analysis: Pre-Post Design

A total of 690 and 356 de-identified patients with VTE were included in the pre- and post- pilot and pre- and post-quality intervention periods, respectively (ESM Table S4). Overall, for patients with PE or DVT there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients discharged between the pre- and post-pilot periods (25.6% vs 27.5%; P = 0.61) (ESM Table S4). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the proportion of patients discharged between pre- and post-quality intervention periods (28.5% vs 29.9%; P = 0.86).

EHR Analysis: Interrupted Time Series

The simple ITS analysis examined the monthly VTE discharge rates pre- and post-pilot intervention using linear regression (ESM Table S5; ESM Fig. S3). The model included an average of 34 patients per month; initially, a statistically significant decline in discharge rate was noted, starting from the index date of 1 January 2021 and continuing until the day of the pilot intervention on 14 October 2021 (β coefficient [B]1 – 0.024; 95% confidence interval [CI] –0.034 to –0.013; P < 0.001). Subsequently, a statistically nonsignificant increase in patient discharge rate was observed immediately post-pilot intervention (Β2 coefficient 0.162; 95% CI – 0.009 to 0.333; P = 0.061). This was followed by a consistent decline throughout the post-pilot phase, with a slope slightly less steep than the pre-pilot period's discharge rate. However, there was no significant difference in the slope of discharge rates between the pre- and post-pilot intervention periods for patients with VTE (Β3 coefficient 0.014; 95% CI – 0.007 to 0.035; P = 0.176). The ITS analysis of monthly discharge rates for the quality intervention revealed comparable findings, showing no statistically significant difference in the slope of VTE discharge rates before and after the quality intervention (ESM Table S6; ESM Fig. S4).

For our controlled ITS analysis, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations were used as an internal control group that would reflect the general care of ED patients; providing an educational initiative on VTE should not have directly affected the COPD measure. In the pre-pilot period, the VTE group had a statistically significant downward trend in discharge rate slope compared with the COPD control group, which had an upward trend (Β5 coefficient – 0.045; 95% CI –0.070 to –0.021; P = 0.001) (ESM Table S7; ESM Fig. S5). Immediately following the pilot intervention, the change in discharge rate for the VTE group was significantly higher than the change in discharge rate for the COPD control group (Β6 coefficient 0.294; 95% CI 0.077–0.512; P = 0.010). In the post-pilot intervention phase, the VTE group had a statistically significant less steep of a decline in discharge rate slope when compared to the COPD control group (Β7 coefficient 0.042; 95% CI 0.009–0.075; P = 0.015).

During the pre-quality intervention education phase, the VTE group had a similar baseline discharge rate compared with the COPD group (Β4 coefficient 0.028; 95% CI – 0.109 to 0.165; P = 0.665) (ESM Table S8; ESM Fig. S6). The discharge rate for the COPD group exhibited a statistically significant upward trend (Β1 coefficient 0.043; 95% CI 0.005–0.081; P = 0.029), while the VTE group displayed a downward trend in comparison; the difference was significant (Β5 coefficient – 0.061; 95% CI – 0.107 to – 0.015; P = 0.013). Immediately following the quality intervention, the COPD group experienced an instantaneous but statistically nonsignificant decrease (Β2 coefficient – 0.051; 95% CI – 0.196 to 0.094; P = 0.460) while the VTE group had an increase in discharge rate; however, these changes were not significantly different (Β6 coefficient 0.147; 95% CI – 0.035 to 0.330; P = 0.104). In the post-quality intervention phase, the discharge rate trend for the COPD group declined in contrast with an upward trend in the pre-quality intervention period. The post-quality intervention discharge rate for the VTE group followed a declining trend, mirroring that in the pre-quality intervention phase. The difference in the slope change between two groups was significant (Β7 coefficient 0.059; 95% CI 0.008–0.109; P = 0.026).

Discussion

This study evaluated how a provider education initiative would improve providers’ clinical knowledge and confidence when assessing whether a patient with VTE in the ED is eligible for outpatient treatment. This provider education initiative led to improvements in both clinical knowledge scores and confidence scores as indicated by the pre- and post-quality intervention surveys. ED providers expressed that a major barrier to discharging patients with VTE to outpatient care was the lack of adequate follow-up appointments. For ED discharge rates, there was a significant increase in the rate of PE-related discharges after the initial pilot. For the ITS analyses of VTE discharge rates pre- and post-pilot intervention, the simple ITS models showed an instantaneous level change after both the pilot and quality interventions, but the controlled ITS demonstrated an instantaneous level change only with the pilot. Both uncontrolled and controlled ITS analyses did not show a sustained change in discharge rates associated with either the pilot or quality interventions.

Various studies have demonstrated improved VTE management through provider educational interventions [12, 13]. However, education alone may not suffice for sustained change in practice. Besides offering educational sessions for ED providers on a continuous basis, we could also explore the use of a decision support tool as well as regular audit-and-feedback mechanisms [14, 15]. In addition, while not investigated in this study, it may also be of interest to evaluate the correlation between changes in individual clinical knowledge scores and related confidence scores to evaluate any relationship between education and confidence. Changes in clinical knowledge scores and confidence scores were only evaluated immediately after the didactic curriculum; follow-up surveys at a later time would better illustrate the durable effect of the provider education initiative. Future directions should prioritize ongoing efforts to ensure the implementation of best practices in caring for this population of patients.

One barrier to discharging patients noted by the providers in the quality intervention surveys was the lack of a dedicated post-discharge appointment with a clinician. While the BSWH Temple ED does have a well-established anticoagulation clinic responsible for managing the discharge needs of patients with uncomplicated VTE, outside of this program, a notable gap exists in the continuity of care, particularly for individuals lacking a primary care provider. Additionally, language barriers exist. While potential language barriers were addressed with development of a patient-centric infographic resource with English and Spanish text, there may still be other cultural aspects that are not addressed by this resource. Socioeconomic barriers, and particularly the cost of medication and insurance coverage, are another serious concern. We overcame this with a process whereby the ED provider could enter a coupon code into Epic for a free 30-day starter pack which is stocked at the nearby 24-h pharmacy.

To address these challenges, the following key strategies should be considered. First, it is crucial to establish robust communication channels between ED providers and outpatient providers, including a process for a scheduled outpatient appointment provided at the time of ED discharge. In our case, we simplified the process by having a 2-week phone appointment, during which the handoff to the primary care provider was facilitated. Second, the ED should offer patients the patient-centric infographic resource that includes comprehensive guidance on medication usage, instructions for follow-up appointments, and essential information about warning signs that demand immediate attention. Encouraging active patient participation in their care plan and underlining the significance of follow-up care are integral aspects. Finally, within the pharmacy domain it is essential to designate a committed champion from the pharmacy team who supports this process. This champion can play a pivotal role in ensuring the smooth execution of the initiative and transition of care for patients. Moreover, the pharmacy department should be well-informed about any available coupons or discounts for anticoagulation medications, contributing to cost-effective and accessible care.

Regarding patient discharge rates, both the pilot and quality interventions were linked to an immediate increase in patient discharge which did not persist over time. Discharge rates to outpatient management for patients with VTE after the quality intervention (8.3% for PE and 53.4% for DVT) remained consistent with findings from previous studies. A study from 2016 to 2019 found that 10% of patients with PE and 18% of patients with DVT were managed at home. Another study from 2011 to 2018 found that outpatient treatment increased from 16% to 23% for PE and from 54% to 65% for DVT [5, 16].

This study’s before-and-after design made it susceptible to history bias, as there was a chance that events besides the study interventions that took place around the same time (during the COVID-19 pandemic) could have influenced the outcomes related to patients with VTE discharges. To alleviate this bias, a COPD patient group was added to serve as a control group for the patients with VTE. Using a concurrent control group, the observed changes were directly compared from pre-intervention to post-intervention during the same time frame in a context where the intervention was not implemented [17]. However, the low average number of patients per month (approximately 34) combined with the short duration of evaluation in the ITS analyses may have resulted in models that were highly sensitive to outliers, and this limits their interpretability.

The growing accessibility of real-world EHR data presents numerous advantages, including improved efficiency in identifying gaps between clinical guidelines and actual practice. Nevertheless, working with real-world EHR data comes with its own set of challenges, such as data reliability and missing information. There is possible indication bias in our study due to the lack of detailed information available for confirming the severity of VTE and the impact of comorbidities and other factors that could have influenced a clinician’s decision regarding whether to treat a VTE case as an inpatient or outpatient. Lack of information regarding comorbidities, such as cancer or pregnancy, likely presented complicating factors in patients who otherwise would have been discharged with a VTE event. This could have led to underestimation of the discharge rate since the comorbidities were not able to be addressed. Information about patients prior to the clinical adoption of the EHR or patients’ treatment outside of BSWH may not have been available. In addition, patients who were placed in observation status were typically managed by inpatient staff regardless of the time in that status and were therefore not counted as direct discharge disposition patients; this may not be consistent with how other sites may manage observation patients and this categorization may need to be reevaluated on a per-site basis.

A limitation is the short length of study, specifically for the pre- and post-quality intervention periods, which were only around 5 months each. Additionally, there were several limitations to working with survey data. In particular, response bias was a possible factor for the pre- and post-survey portion of the study in which ED providers voluntarily reported their clinical knowledge, confidence, and barriers regarding discharging patients with VTE to outpatient care. Response bias was partially mitigated by the anonymity of the surveys and the respondents' lack of prior knowledge about the surveys’ content or study objectives. Prior to the administration of the surveys, the survey content had been reviewed by several BSWH clinicians; however, the wording of the survey questions, depending on the providers’ interpretations, could have yielded inaccurate and misleading data.

Conclusions

While this quality intervention evaluation yielded promising outcomes, there remains a need for further efforts to ensure that eligible patients with VTE receive appropriate outpatient care post-discharge. Despite the instantaneous uptick in discharge rates after the interventions, the change did not have a long-lasting effect. This suggests that providing tools to address medication and continuity barriers may not be sufficient alone; the addition of periodic education and assessments of the performance of the clinical pathway may ensure continued success of the program. While provider education is valuable, sustained practice change may necessitate the incorporation of decision support tools and regular audit-and-feedback mechanisms. Future efforts should focus on ensuring the consistent implementation of best practices for this patient population.

Data Availability

The dataset used in this study is derived from the electronic health records of Baylor Scott & White Health. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethics considerations.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data and statistics on venous thromboembolism. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/dvt/data.html Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e419S-e496S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-2301.

Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026.

HCUPnet Data Tools/AHRQ Data Tools. https://datatools.ahrq.gov/hcupnet. Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

Kline JA, Adler DH, Alanis N, et al. Monotherapy anticoagulation to expedite home treatment of patients diagnosed with venous thromboembolism in the emergency department: a pragmatic effectiveness trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2021;14(7):e007600. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.007600.

Kline JA, Kahler ZP, Beam DM. Outpatient treatment of low-risk venous thromboembolism with monotherapy oral anticoagulation: patient quality of life outcomes and clinician acceptance. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:561–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S104446.

Kea B, Alligood T, Robinson C, Livingston J, Sun BC. Stroke prophylaxis for atrial fibrillation? To prescribe or not to prescribe-a qualitative study on the decisionmaking process of emergency department providers. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(6):759–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.03.026.

Falconieri L, Thomson L, Oettinger G, et al. Facilitating anticoagulation for safer transitions: preliminary outcomes from an emergency department deep vein thrombosis discharge program. Hosp Pract (1995). 2014;42(4):16–45. https://doi.org/10.3810/hp.2014.10.1140.

Pellathy T, Saul M, Clermont G, Dubrawski AW, Pinsky MR, Hravnak M. Accuracy of identifying hospital acquired venous thromboembolism by administrative coding: implications for big data and machine learning research. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022;36(2):397–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10877-021-00664-6.

Wei WT, Lin SM, Hsu JY, et al. Association between hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state and venous thromboembolism in diabetes patients: a nationwide analysis in Taiwan. J Pers Med. 2022;2(2):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12020302.

Raghupathy S, Barigidad AP, Doorgen R, et al. Prevalence, trends, and outcomes of pulmonary embolism treated with mechanical and surgical thrombectomy from a nationwide inpatient sample. Clin Pract. 2022;12(2):204–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract12020024.

Maynard GA, Morris TA, Jenkins IH, et al. Optimizing prevention of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE): prospective validation of a VTE risk assessment model. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(1):10–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.562.

Dobesh PP, Stacy ZA. Effect of a clinical pharmacy education program on improvement in the quantity and quality of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for medically ill patients. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(9):755–62. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.9.755.

Kabrhel C, Vinson DR, Mitchell AM, et al. A clinical decision framework to guide the outpatient treatment of emergency department patients diagnosed with acute pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis: results from a multidisciplinary consensus panel. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(6):e12588. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12588.

Timmons S, O’Callaghan C, O’Connor M, O’Mahony D, Twomey C. Audit-guided action can improve the compliance with thromboembolic prophylaxis prescribing to hospitalized, acutely ill older adults. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(9):2112–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01472.x.

Lutsey PL, Walker RF, MacLehose RF, et al. Inpatient versus outpatient acute venous thromboembolism management: trends and postacute healthcare utilization from 2011 to 2018. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(20): e020428. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.020428.

Mascha EJ, Sessler DI. Segmented regression and difference-in-difference methods: assessing the impact of systemic changes in health care. Anesth Analg. 2019;129(2):618–33. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004153.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Editorial/medical writing support was provided by Denise Kenski, PhD, of Nucleus Global, and was funded by Pfizer. Additional support for data analysis and study design was provided by Tim Reynolds, PharmD, MS, and Ryan Thaliffdeen, PharmD, MS, from Baylor Scott & White Health, independent of funding.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc, New York, NY, USA, who is also funding the Rapid Service Fee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization/design of study: Anthony Yu, Krista L. Birkemeier, J. Rebecca Mills, Tiffany Kuo, Nina Tachikawa, Feng Dai, Karishma Thakkar, Christian Cable, Allison Brenner, and Paul J. Godley. Data analysis: Anthony Yu, Tiffany Kuo, Karishma Thakkar, and Feng Dai. Anthony Yu, Krista L. Birkemeier, J. Rebecca Mills, Tiffany Kuo, Nina Tachikawa, Feng Dai, Karishma Thakkar, Christian Cable, Allison Brenner, and Paul J. Godley were involved in interpreting the data, critically reviewing the manuscript, and approving the final version for submission. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

J. Rebecca Mills, Nina Tachikawa, Feng Dai, and Allison Brenner are employees of and shareholders in Pfizer, Inc. Anthony Yu, Krista L. Birkemeier, Tiffany Kuo, Karishma Thakkar, Christian Cable, and Paul J. Godley declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The Baylor Scott & White institutional review board assessed the protocol (023-032) to qualify for expedited review as it posed minimal risk to study participants. All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study. The informed consent documents used during the informed consent process and any participant recruitment materials were reviewed and approved by Pfizer and by the institutional review board/independent ethics committee before use. The Baylor Scott & White institutional review board approved this study (IRB ID: 023-032). This study was conducted at the Baylor Scott & White Temple hospital. This evaluation was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value, and rigor and follow generally accepted research practices described in Good Practices for Outcomes Research issued by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research and in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, A., Birkemeier, K.L., Mills, J.R. et al. Implementing a Quality Intervention to Improve Confidence in Outpatient Venous Thromboembolism Management. Cardiol Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-024-00370-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-024-00370-9