Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic disorder caused by pathogenic variants in sarcomeric genes, leading to left ventricular hypertrophy and complex phenotypic heterogeneity. While HCM is the most common inherited cardiomyopathy, pharmacological treatment options have previously been limited and were predominantly directed towards symptom control owing to left ventricular outflow obstruction. These therapies, including beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and disopyramide, have not been shown to affect the natural history of the disease, which is of particular concern for younger patients who have an increased lifetime risk of experiencing arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death. Increased knowledge of the genetic mechanisms underlying this disease in recent years has led to the development of targeted, potentially disease-modifying therapies for both obstructive and nonobstructive phenotypes that may help to prevent or ameliorate left ventricular hypertrophy. In this review article, we will define the etiology and clinical phenotypes of HCM, summarize the conventional therapies for obstructive HCM, discuss the emerging targeted therapies as well as novel invasive approaches for obstructive HCM, describe the therapeutic advances for nonobstructive HCM, and outline the future directions for the treatment of HCM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Cardiac myosin inhibitors are a novel class of targeted therapies that reduce left ventricular hypercontractility, and as of April 2022, the first-in-class agent mavacamten is now approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of adult patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–III symptoms. |

Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are being studied for their potential role in reducing myocardial hypertrophy and ultimately slowing disease progression via inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-b). |

Advances in invasive techniques including percutaneous septal radiofrequency ablation and transcatheter myotomy have provided alternative approaches for reducing left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction in patients who are not candidates for traditional surgical septal myectomy. |

Cardiac gene replacement therapy utilizing adeno-associated viruses (AAV) has shown promise for HCM-associated myosin binding protein C3 (MYBPC3) variants in mice and human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. |

Treatment of nonobstructive HCM remains a major unmet need, and there is active research into the development of cardiac mitotropes to improve myocardial metabolic efficiency. |

Introduction

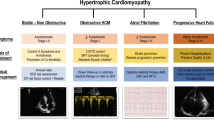

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a myocardial disorder characterized by increased ventricular wall thickness, is one of the most common inherited cardiovascular diseases. Since the initial discovery of HCM in the 1950s, there has been significant advancement in our understanding of the etiology and pathophysiology of the disease. This knowledge has fueled an evolution in the approach to treatment, from minimizing symptoms to slowing disease progression to developing targeted molecular therapies to alter the natural history of the disease. In this article, we will review the major phenotypes of HCM, describe conventional treatment strategies, and discuss emerging novel therapies that will allow for disease-specific treatment and change the future management of HCM (Fig. 1).

Definition and Etiology

HCM is defined by a left ventricular wall thickness of > 15 mm in the absence of secondary causes, and is estimated to have a prevalence of at least 1 case per 500 persons in the general population, and perhaps as high as 1 in 250 if genotype positive, phenotype negative individuals are included [1, 2]. HCM is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, and between 30% and 60% of HCM in adults is caused by variants in genes that encode thick and thin myofilament components of the cardiac sarcomere [3, 4]. Genetic variation in genes that encode sarcomeric proteins accounts for the majority of genetic HCM. Pathogenic variants in the MYH7 (myosin heavy chain 7) and MYBPC3 (myosin binding protein C3) genes comprise approximately half of the causal variants in patients with familial HCM [5,6,7]. Some inherited metabolic diseases (Danon disease, Anderson–Fabry disease), neuromuscular diseases (Friedreich ataxia), and mitochondrial diseases demonstrate a clinical phenotype with left ventricular hypertrophy that mimics that of sarcomeric HCM. However, it is important to differentiate these phenocopies from HCM as the causal genetics, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatment are different, and these conditions will not be reviewed herein. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Clinical Manifestations and Phenotypes

HCM has heterogeneous phenotypic expression, and as such, clinical manifestations are highly variable. The majority of patients with HCM are currently undiagnosed. For those who are asymptomatic, diagnosis may only be made after incidental discovery of a heart murmur, abnormal electrocardiogram (EKG), or suggestive family history [2]. Symptoms secondary to HCM are commonly attributed to left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, diastolic ventricular dysfunction, an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand, or arrhythmia. Common symptoms include exertional dyspnea, chest pain, fatigue, palpitations, dizziness, and syncope.

HCM has been historically classified into two hemodynamic subsets: obstructive and nonobstructive. Obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is characterized by dynamic LVOT obstruction with an LVOT peak pressure gradient > 30 mmHg. [8] Approximately one-third of patients with HCM have resting LVOT obstruction, predominantly due to systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve [2, 9, 10]. Other causes of LVOT obstruction include severe interventricular septal hypertrophy, papillary muscle hypertrophy and displacement, and intrinsic mitral leaflet abnormalities [4]. Another one-third of patients with HCM have obstruction with provocation only (i.e., latent obstruction) [11]. In these patients, LVOT obstruction may be provoked by a decrease in preload/afterload, such as with Valsalva maneuver and nitrate administration, or with an increase in contractility during exercise. The remaining one-third of patients with HCM have no significant obstruction either at rest or with provocation, with a peak LVOT gradient < 30 mmHg.

With the recent progress in treatment modalities and surgical techniques, the mortality associated with HCM has significantly reduced. HCM-related death has been reduced from approximately 6% per year to 0.5% per year [12]. Although the overall mortality rate has decreased, there remains a significant burden of disease from morbidity, most commonly from atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Continued advances towards targeted therapies is essential to limit disease progression and adverse outcomes, especially in younger populations with known causal genetic variants who are at highest risk for HCM-related morbidity and mortality. [13]

Conventional Therapy for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy with Obstruction

Pharmacologic Therapy

Therapeutic goals in HCM include improvement of symptoms, function, and quality of life. Pharmacological therapy has been the mainstay of treatment for patients with obstructive HCM requiring symptom control, with the goal of lessening or eliminating the LVOT gradient through negative inotropy. Nonvasodilating beta-blockers (e.g., metoprolol, propranolol, atenolol) are among the most commonly used and effective therapies as they reduce LVOT obstruction and prolong diastole through their negative inotropic and chronotropic effects, respectively. [14] Beta-blockers are particularly effective with latent obstruction provoked by exercise but may improve resting gradients as well [2]. In a randomized crossover trial in which patients with obstructive HCM received either metoprolol or placebo for 2 weeks, patients treated with metoprolol had significantly reduced LVOT gradient at rest (25 versus 72 mmHg) and with exercise (28 versus 62 mmHg), improved New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, and improved overall quality of life, compared with those on placebo [15]. Nondihydropyridine calcium receptor antagonists (i.e., verapamil and diltiazem) are a reasonable alternative if beta-blockers are not tolerated or contraindicated. Disopyramide, a Class Ia antiarrhythmic with potent negative inotropic effects, can be added in combination with a beta-blocker or verapamil if symptoms persist [16]. Initiation may require hospitalization to monitor for proarrhythmic effects and QT prolongation, and disopyramide is sometimes poorly tolerated due to its anticholinergic side effects [8]. While these therapies can provide symptom relief, there is little evidence that they can alter the natural history of HCM. [2]

In addition, nonpharmacological interventions are also important to minimize obstructive symptoms. These include maintaining adequate hydration, performing mild- to moderate-intensity exercises, avoiding excess alcohol intake, maintaining a healthy body weight, and avoiding situations that elicit sudden changes in cardiac preload such as rapid postural changes that may exacerbate obstruction. [1]

Septal Reduction Therapy

For patients with NYHA III–IV symptoms despite maximal medical therapy, septal reduction therapies are indicated for symptomatic relief [4, 16]. The two most common septal reduction methods are surgical septal myectomy and alcohol septal ablation.

Septal myectomy is a well-established therapy for HCM, and was first performed in the 1960s. It is performed by resecting a small amount of muscle from the proximal ventricular septum, which widens the LVOT and relieves LVOT obstruction [17]. Surgical technique has evolved over the past 50 years, with the incision now extended apically toward the base of the papillary muscle and leftward toward the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve, which allows the surgeon to address abnormalities (such as anomalous chordal structures or fibrous structures at the leaflets) at the time of surgery [18]. The most feared complication of septal myectomy is ventricular septal defect, with the main risk factors for this outcome including multiple concurrent surgical interventions and septal thickness < 20 mm. [19] With improvements in surgical technique over time, the average reduction of LVOT gradient is 90% [18] and myectomy-associated mortality has lowered to 1–2% in experienced centers. [20]

Alcohol septal ablation (ASA) is an alternative and more recent septal reduction technique. In ASA, 96% ethanol is selectively infused into a septal branch of the left anterior descending coronary artery supplying the basal interventricular septum [19]. This produces an iatrogenic infarct and ultimate resolution of obstruction over the course of several months with septal remodeling [17]. Similar to surgical septal myectomy, ASA has a low mortality rate of < 1% at experienced centers [21]. There is a high incidence of temporary complete atrioventricular block during septal ablation, estimated to be about 50% [20], with 12% of patients requiring permanent pacemaker placement [22, 23]. Additionally, complete resolution of LVOT obstruction is less frequently achieved with ASA compared with myectomy, with an average residual resting gradient of 20–25 mmHg post-ASA versus 0–10 mmHg post-myectomy. [17, 24, 25]

The decision regarding which septal reduction therapy to pursue is individualized and should consider cardiac anatomy as well as patient comorbidities and preference. In general, ASA is typically favored if the patient is older [26], has comorbid noncardiac conditions that increase the risk of adverse postsurgical outcomes, has a preexisting right bundle branch block, or a prior pacemaker placed [27]. Myectomy is favored for patients who are younger, have severe septal hypertrophy (> 30 mm) [26, 28], require surgical intervention for other cardiac conditions (i.e., mitral valve abnormalities), or have a preexisting left bundle branch block. [29]

Emerging Molecular Therapies for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

The discovery of the genetic mechanisms of HCM has led to accelerating interest in the development of targeted molecular therapeutics to improve symptoms and cardiac function, and to potentially positively alter the disease course (Table 1).

Cardiac Myosin Inhibitors

Cardiac myosin inhibitors are a new class of disease-specific therapies that target left ventricular hypercontractility. Cardiac contractility is mediated by myosin, a motor protein containing ATPase, which hydrolyzes ATP to form actin-myosin cross bridges [30]. This process ultimately leads to sarcomere shortening and muscle contraction. In HCM, most causal genetic variants lead to an increase in actin-myosin cross bridge formation and thus hyperdynamic contraction [31]. MYH7 (cardiac B-myosin heavy chain) is the predominant myosin isoform expressed in the heart, and MYBPC (myosin-binding protein C) is a modulator of cardiac contraction [32]. Deleterious variants in the genes that encode these and other sarcomeric proteins cause increased myosin involvement in the cardiac cycle and hypercontractility.

Mavacamten (MYK-461), is a reversible, selective allosteric inhibitor of myosin ATPase, thereby reducing cardiac contractility [33, 34]. It was initially studied in a murine HCM model, in which it demonstrated decreased hypercontractility as well as blunted development of ventricular hypertrophy [33]. In the phase 2 proof-of-concept PIONEER-HCM, mavacamten significantly reduced post-exercise LVOT gradients and symptoms while improving exercise capacity in patients with obstructive HCM [35]. Based on these results, the phase 3 EXPLORER-HCM trial, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, enrolled 251 patients with severe symptomatic obstructive HCM with LVOT gradient > 50 mm Hg. Patients were randomized to mavacamten or placebo in addition to their prior beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker. After 30 weeks of treatment, twice as many patients on mavacamten met the primary endpoint of improved functional capacity measured by cardiopulmonary exercise testing and symptom burden. Additionally, 34% more patients in the mavacamten group experienced symptom improvement by at least one NYHA class [36]. Overall, this study demonstrated that mavacamten is superior to placebo with regard to the study endpoints, is well tolerated, and is associated with a significant reduction in post-exercise LVOT gradient. Furthermore, in the recent phase 3 clinical trial VALOR-HCM studying patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM on maximal medical therapy and referred for SRT, treatment with mavacamten for 16 weeks was shown to significantly improve symptoms and reduce the need for SRT [37]. In April 2022, mavacamten was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as a first-in-class therapy for the treatment of adult patients with obstructive HCM and NYHA class II–III symptoms. Mavacamten is primarily metabolized through CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, and therefore caution should be used with concomitant administration of CYP inhibitors and inducers. As mavacamten reduces cardiac contractility, it carries a risk of systolic heart failure and as such it is only available under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). This restricted program ensures that there is monitoring for systolic dysfunction with periodic echocardiograms and screening for drug interactions prior to each dispense.

Aficamten (CK-274) is a next-generation selective cardiac myosin inhibitor. Similar to mavacamten, aficamten binds to the ATP binding pocket of myosin to stabilize a myosin off-state and theoretically reduce cardiac contractility [38]. Compared with mavacamten, it has a shorter half-life, achieves steady state within 2 weeks, and may have a wider therapeutic window [39, 40]. Additionally, studies have shown that it has no substantial CYP450 induction or inhibition, potentially providing less drug–drug interaction compared with mavacamten. In the phase 2, randomized placebo-controlled REDWOOD-HCM trial, nearly all patients treated with aficamten for 10 weeks had elimination of resting LVOT gradients (93% response rate in the high-dose cohort) compared with 8% in the placebo arm. A substantial number of patients also achieved improvement in NYHA class [40]. A phase 3 clinical trial, SEQUOIA-HCM, is an ongoing international, multicenter clinical trial designed to evaluate aficamten in patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM on background medical therapy for 24 weeks. It began enrolling patients in February 2022 and is expected to enroll 270 patients [41].

With the landmark findings of mavacamten, it is likely that there will be further development of other selective myosin inhibitors in the near future. MYK-581 and MYK-224 are two other small molecule myosin inhibitors with similar properties to mavacamten and are under investigation [42, 43]. MYK-224 is in a phase 1 trial, and MYK-581 is collecting preliminary preclinical data [4].

Ion Channel Inhibitors

HCM cardiomyocytes have enhanced late sodium current activity due to enzyme-induced sodium-channel phosphorylation [45]. This leads to increased levels of intracellular calcium via ion exchange, which ultimately leads to increased arrhythmogenicity [46].

Both ranolazine and eleclazine inhibit late sodium current activity, and thus could in theory counteract diastolic and microvascular dysfunction and promote myocardial relaxation [46]. A small pilot study, the RHYME trial, treated symptomatic HCM patients with ranolazine for 2 months and found improvement in angina and heart failure symptoms [47]. A larger, multicenter double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) (RESTYLE HCM) was performed that enrolled 80 patients randomized to placebo or ranolazine, but investigators did not find a significant difference in the end point (exercise capacity assessed by VO2) between the ranolazine and placebo groups [48]. A similar study, LIBERTY-HCM, was conducted to compare the more potent late sodium current activity inhibitor, eleclazine, to placebo, but it was found to be ineffective [49].

While currently no drugs that target ion channels have proven to be effective treatment for HCM, it is certainly a possible area for future novel therapeutics.

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers

Sarcomeric HCM in mouse models have shown that myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis is largely mediated by transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-b) [50, 51]. Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are known to inhibit TGF-b activation, and thus it has been theorized that this class of medications may help slow the progression or even prevent the emergence of HCM. The INHERIT trial, a large single-center randomized trial of losartan in obstructive and nonobstructive patients, failed to demonstrate a beneficial effect on LV mass or exercise capacity [52]. It was theorized that the lack of benefit was because the hypertrophy was already established with full phenotypic expression [53, 54]. The VANISH trial, a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, enrolled 178 patients with early-stage sarcomeric HCM and randomized them to valsartan or placebo. Treatment with valsartan improved the primary composite outcome of cardiac structure/function and remodeling (based on nine distinct measures) compared with placebo [54]. Additional recent meta-analyses have shown that ARB treatment was associated with significant reduction in left ventricular mass in patients with HCM [55]. While additional randomized control trials with larger sample sizes are being conducted to assess the validity and applicability of these results, early initiation of ARB therapy should be considered to potentially slow disease progression.

Advances in Septal Reduction Therapies

In addition to novel pharmacotherapy, there have been recent advances in invasive techniques to treat patients with drug-refractory obstructive symptoms. Both ASA and septal myectomy have limitations with regard to patient selection and requisite septal anatomy [56]. This has led to a desire to develop alternative invasive techniques to reduce LVOT obstruction.

Percutaneous Septal Radiofrequency Ablation

Radiofrequency ablation is a technique that has been used for many years for the treatment of various cardiac arrhythmias [57]. The technique utilizes electroanatomic mapping systems for specified myocardial targeting, which helps to limit complications necessitating pacemaker placement [58]. The first reported study using radiofrequency septal ablation was in 2011 and consisted of 19 inoperable patients with drug-refractory symptoms. Patients had a small reduction in septal width, but a significant reduction in resting gradient from 77 to 27 mmHg, as well as provoked gradient 158 to 164 mmHg. [59] A recent large, open-label, single-arm study recruited 200 patients with HCM with drug-refractory symptoms, LVOT gradient > 50 mmHg, and NYHA class II or higher. At the median time of follow-up (19 months), maximal septal thickness was reduced from 24 to 17 mm, LVOT gradient was decreased from 79 to 14 mmHg, and over 96% of patients were NYHA class I or II at follow-up [60]. These results are encouraging, and further study to compare this invasive technique with the other established septal reduction techniques will be necessary.

Transcatheter Myotomy

Transcatheter myotomy is another novel technique under investigation to help reduce LVOT obstruction, particularly as an alternative for patients who are poor surgical candidates. Prior to septal myectomy, the surgical technique involved a myotomy in which circumferential myofibers were splayed apart to reduce septal encroachment and ultimately improve LVOT obstruction [61]. Based on this idea, a novel transcatheter procedure known as Septal Scoring Along the Midline Endocardium (SESAME) was recently developed [62]. This procedure utilizes coronary guiding catheters and guidewires to mechanically enter the basal interventricular septum, and then lacerates the myocardium with transcatheter electrosurgery to create the myotomy. A recent preclinical study performed this procedure in five naïve pigs and five pigs with percutaneous aortic banding-induced left ventricular hypertrophy, and achieved increased left ventricular outflow tract area (753–854 mm2, P = 0.008) in all animals [62]. Additionally, no ventricular septal defects developed in the hypertrophy model pigs, there was no evidence of conduction block on electrocardiography, and coronary artery branches were intact on angiography [62]. The first human case of transcatheter septal myotomy was reported as of May 2022 in an 80-year old woman with obstructive HCM for whom surgery was risk prohibitive. SESAME was successfully used to enlarge the LVOT, relieve the LVOT gradient from the hypertrophied septum, and allow for total mitral valve replacement without complication [63].

Gene Therapy

The appeal of gene therapy as a means to permanently cure hereditary disease has led to numerous international clinical trials for various diseases. HCM is predominantly an autosomal dominant disorder, and research has shown a majority of causal variants to be in MYBPC3 and MYH7. As such, these may serve as intriguing targets for cardiac gene therapy [64]. This is particularly true for patients who have double or compound heterozygosity (i.e., two distinct variants in the same or different sarcomere genes) who have been shown to have earlier onset and more severe disease progression [65].

Over the past decade, there has been significant development in different gene therapy strategies. These include genome editing, allele-specific silencing, spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing, exon skipping, and gene replacement [64]. Cardiac gene therapy utilizes adeno-associated viruses (AAV) as the viral vectors as they have very low pathogenicity in human hosts [66]. Of the various strategies, gene replacement with AAV9 has shown promise for HCM-associated MYBPC3 variants. Studies have shown success with both mice and human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes [67,68,69]. While further testing with large animal models are still required to test AAV doses and delivery before human testing, this may be a potential therapeutic option in the future for a selected subset of patients with genetic HCM.

Advances in Management of Nonobstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Approximately one-third of patients with HCM do not have evidence of obstruction at rest or with provocation. Pharmacotherapy has typically been reserved for symptomatic patients, and includes beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers with the addition of diuretics if congestion is present. Those who develop end-stage heart failure may have a hypokinetic and/or restrictive phenotype associated with a poor prognosis and typically responds poorly to conventional systolic heart failure treatment [13]. For these patients, transplantation is often the only definitive option.

While it was previously thought that nonobstructive was more benign than obstructive HCM, a recent meta-analysis of 7731 patients showed no difference in the risk of heart failure-associated deaths in patients with nonobstructive compared with obstructive disease [70]. Annual mortality among patients with nonobstructive HCM has been shown to be low (0.5% per year), with a 10‐year survival rate of 97%. However, recent studies have shown that these patients have high rates of morbidity and adverse cardiac events similar to those with obstructive HCM. Notably, patients with nonobstructive HCM have been shown to have higher risk of arrhythmia [71]. Therefore, it is crucial to develop targeted therapies for patients with symptomatic nonobstructive HCM as well.

One trial designed to address this unmet need is IMPROVE-HCM. This phase 2 clinical trial investigates the drug IMB-101 in patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. IMB-101 is a cardiac mitotrope that is a partial fatty acid oxidation (pFOX) inhibitor. It improves myocardial metabolic efficiency by reducing fatty acid oxidation in favor of glucose oxidation to generate more ATP per unit of oxygen [72]. The efficacy of the drug will be measured by the change from baseline of peak oxygen consumption and oxygen uptake efficiency slope by cardiopulmonary exercise testing after 12 weeks. IMPROVE-HCM is currently enrolling patients with an estimated completion date of November 2022.

The phase 2, dose finding MAVERICK-HCM trial of mavacamten in nonobstructive HCM showed that myosin inhibitors are well tolerated in patients without obstruction, and also resulted in significant reductions in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and troponin levels, suggesting an improvement in filling pressures and wall stress [73]. The REDWOOD-HCM cohort 4 study of aficamten in nonobstructive HCM is ongoing [74].

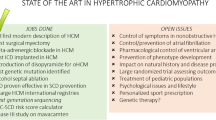

Future Directions and Conclusions

The therapeutic landscape of HCM management has seen rapid expansion in the last 5 years, with multiple novel therapies under investigation and the regulatory approval of a first-in-class cardiac myosin inhibitor designed specifically to treat obstructive HCM. There are also existing therapies being studied as potential therapeutic options for HCM, including the effects of both sodium–glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors and sacubitril/valsartan on cardiac remodeling (Table 2) [75, 76]. Localized ionizing radiation that is commonly used to target tumors is also being investigated as an alternative to conventional septal reduction therapy [77]. With continued research into the genetic architecture underlying HCM, there will be continued progress towards the development of targeted therapies that have the ability to attenuate and, ideally, change the natural course of the disease.

References

Maron BJ, Ommen SR, Semsarian C, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: present and future, with translation into contemporary cardiovascular medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(1):83–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.003.

Maron BJ. Clinical course and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(7):655–68. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1710575.

Sherrid MV. Drug therapy for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: physiology and practice. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2016;12(1):52–65. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573403x1201160126125403.

Makavos G, Κairis C, Tselegkidi ME, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an updated review on diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Heart Fail Rev. 2019;24(4):439–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-019-09775-4.

Muresan ID, Agoston-Coldea L. Phenotypes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: genetics, clinics, and modular imaging. Heart Fail Rev. 2021;26(5):1023–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-020-09931-1.

Marian AJ, Braunwald E. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: genetics, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and therapy. Circ Res. 2017;121(7):749–70. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311059.

Medical Masterclass contributors, Firth J. Cardiology: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19(1):61–3. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.19-1-61.

Geske JB, Ommen SR, Gersh BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: clinical update. JACC. 2018;6(5):364–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2018.02.010.

Maron MS, Maron BJ. Clinical impact of contemporary cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2015;132(4):292–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014283.

Sherrid MV, Balaram S, Kim B, et al. The mitral valve in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a test in context. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(15):1846–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.071.

Nishimura RA, Seggewiss H, Schaff HV. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: surgical myectomy and septal ablation. Circ Res. 2017;121(7):771–83. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309348.

Maron MS, Rowin EJ, Olivotto I, et al. Contemporary natural history and management of nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(12):1399–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.023.

Ho CY, Day SM, Ashley EA, et al. Genotype and lifetime burden of disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: insights from the sarcomeric human cardiomyopathy registry (SHaRe). Circulation. 2018;138(14):1387–98. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033200.

Zampieri M, Berteotti M, Ferrantini C, et al. Pathophysiology and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: new perspectives. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2021;18(4):169–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-021-00523-0.

Dybro AM, Rasmussen TB, Nielsen RR, et al. Randomized trial of metoprolol in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(25):2505–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.065.

Ommen S, Mital S, Burke M, et al. 2020 AHA/ACC guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):e159–240. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000937.

Maron BJ. Surgical myectomy remains the primary treatment option for severely symptomatic patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2007;116(2):196–206. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691378.

Fitzgerald P, Kusumoto F. The effects of septal myectomy and alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy on the cardiac conduction system. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2018;52(3):403–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-018-0433-0.

Arévalos V, Rodríguez-Arias JJ, Brugaletta S, et al. Alcohol septal ablation: an option on the rise in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Clin Med. 2021;10(11):2276. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10112276.

Panaich SS, Badheka AO, Chothani A, et al. Results of ventricular septal myectomy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114(9):1390–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.075.

Kim LK, Swaminathan RV, Looser P, et al. Hospital volume outcomes after septal myectomy and alcohol septal ablation for treatment of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: US nationwide inpatient database, 2003–2011. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(3):324–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0252.

Veselka J, Jensen MK, Liebregts M, et al. Long-term clinical outcome after alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: results from the Euro-ASA registry. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(19):1517–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv693.

Alam M, Dokainish H, Lakkis N. Alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a systematic review of published studies. J Interv Cardiol. 2006;19(4):319–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8183.2006.00153.x.

Van der Lee C, ten Cate FJ, Geleijnse ML, Kofflard MJ, Pedone C, van Herwerden LA, Biagini E, Vletter WB, Serruys PW. Percutaneous versus surgical treatment for patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy and enlarged anterior mitral valve leaflets. Circulation. 2005;112(4):482–8. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.104.508309.

Ralph-Edwards A, Woo A, McCrindle BW, et al. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: comparison of outcomes after myectomy or alcohol ablation adjusted by propensity score. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129(2):351–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.08.047.

Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124(24):e783–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.011.

Chen AA, Palacios IF, Mela T, et al. Acute predictors of subacute complete heart block after alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(2):264–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.08.032.

Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the task force for the diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(39):2733–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284.

Fifer MA. Choice of septal reduction therapies and alcohol septal ablation. Cardiol Clin. 2019;37(1):83–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccl.2018.08.009.

Toepfer CN, Garfinkel AC, Venturini G, et al. Myosin sequestration regulates sarcomere function, cardiomyocyte energetics, and metabolism, informing the pathogenesis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2020;141:828–42. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042339.

Zampieri M, Argirò A, Marchi A, et al. Mavacamten, a novel therapeutic strategy for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021;23(7):79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-021-01508-0.

García-Giustiniani D, Arad M, Ortíz-Genga M, et al. Phenotype and prognostic correlations of the converter region mutations affecting the β myosin heavy chain. Heart. 2015;101(13):1047–53. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307205.

Green EM, Wakimoto H, Anderson RL, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of sarcomere contractility suppresses hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Science. 2016;351:617–21. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad3456.

Argirò A, Zampieri M, Berteotti M, et al. Emerging medical treatment for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):951. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10050951.

Heitner SB, Jacoby D, Lester SJ, et al. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):741–8. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-3016.

Olivotto I, Oreziak A, Barriales-Villa R, et al. Mavacamten for treatment of symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (EXPLORER-HCM): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10253):759–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31792-X.

Desai M, Owens A, Geske J, et al. Myosin inhibition in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy referred for septal reduction therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(2):95–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.04.048.

Hartman J, et al. Characterization of the cardiac myosin inhibitor CK-3773274: a potential therapeutic approach for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Biophys J. 2020;118(3):596a. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2019.11.3225.

Chuang C, Collibee S, Ashcraft L, et al. Discovery of aficamten (CK-274), a next-generation cardiac myosin inhibitor for the treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Med Chem. 2021;64(19):14142–52. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01290.

Maron M. Redwood HCM: results from cohorts 1&2. In: Oral presentation, HFSA 2021 Annual Scientific Meeting. Sept 10–13, 2021.

Siegall J. Cytokinetics announces start of SEQUOIA-HCM, a phase 3 clinical trial of aficamten in patients with symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. https://ir.cytokinetics.com/news-releases/news-release-details/cytokinetics-announces-start-sequoia-hcm-phase-3-clinical-trial. Accessed 23 Feb 2022.

Ferguson BS, Stern JA, Oldach MS, et al. Acute effects of a mavacamten-like myosin-inhibitor MYK-581 in a feline model of obstructed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: evidence of improved ventricular filling (beyond obstruction reprieve). Eur Heart J. 2020;41(2):339–43. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.99.2.254.

Del Rio CL, Yadav A, Ferguson B, et al. Chronic treatment with a mavacamten-like myosin-modulator (MYK-581) blunts disease progression in a mini-pig genetic model of non-obstructed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: in vivo evidence for improved relaxation and functional reserve. Circulation. 2019;140(1):A14585.

Lehman SJ, Crocini C, Leinwand LA. Targeting the sarcomere in inherited cardiomyopathies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19(6):353–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-022-00682-0.

Coppini R, Ferrantini C, Yao L, et al. Late sodium current inhibition reverses electromechanical dysfunction in human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2013;127(5):575–84. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.134932.

Tuohy CV, Kaul S, Song HK, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the future of treatment. Eur Jour Heart Fail. 2020;22(2):228–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1715.

Gentry JL III, Mentz RJ, Hurdle M, et al. Ranolazine for treatment of angina or dyspnea in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients (RHYME). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1815–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.07.758.

Olivotto I, Camici PG, Merlini PA, et al. Efficacy of ranolazine in patients with symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the RESTYLE-HCM randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(1): e004124. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004124.

Olivotto I, Hellawell JL, Farzaneh-Far R, et al. Novel approach targeting the complex pathophysiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the impact of late sodium current inhibition on exercise capacity in subjects with symptomatic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (LIBERTY-HCM) trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(3): e002764. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002764.

Kim JB, Porreca GJ, Greenway SC, et al. Polony multiplex analysis of gene expression (PMAGE) in mouse hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Science. 2007;316(5830):1481–4. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1137325.

Teekakirikul P, Eminaga S, Toka O, et al. Cardiac fibrosis in mice with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is mediated by non-myocyte proliferation and requires Tgf-β. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(10):3520–9. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI42028.

Axelsson A, Iversen K, Vejlstrup N, et al. Efficacy and safety of the angiotensin II receptor blocker losartan for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the INHERIT randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(2):123–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70241-4.

Kawano H, Toda G, Nakamizo R, et al. Valsartan decreases type I collagen synthesis in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2005;69(10):1244–8. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.69.1244.

Ho CY, Day SM, Axelsson A, et al. Valsartan in early-stage hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2021;27(10):1818–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01505-4.

Abdelazeem B, Abbas KS, Ahmad S, et al. The effect of angiotensin II receptor blockers in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2022;23(4):141. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm2304141.

Chan W, Williams L, Kotowycz MA, et al. Angiographic and echocardiographic correlates of suitable septal perforators for alcohol septal ablation in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:912–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2014.04.008.

Yang H, Yang Y, Xue Y, Luo S. Efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43(5):450–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.23341.

Cooper RM, Stables RH. Non-surgical septal reduction therapy in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2018;104(1):73–83. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309952.

Lawrenz T, Borchert B, Leuner C, et al. Endocardial radiofrequency ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: acute results and 6 months’ follow-up in 19 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(5):572–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.055.

Zhou M, Ta S, Hahn R, et al. Percutaneous intramyocardial septal radiofrequency ablation in patients with drug-refractory hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7(5):529–38. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0259.

Morrow AG, Brockenbrough EC. Surgical treatment of idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis: technic and hemodynamic results of subaortic ventriculomyotomy. Ann Surg. 1961;154:181–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-196108000-00003.

Khan J, Bruce C, Greenbaum A, et al. Transcatheter myotomy to relieve left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: the septal scoring along the midline endocardium procedure in animals. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15(6): e011686. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011686.

Greenbaum AB, Khan JM, Bruce CG, et al. Transcatheter myotomy to treat hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and enable transcatheter mitral valve replacement: first-in-human report of septal scoring along the midline endocardium. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15(6): e012106. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012106.

Prondzynski M, Mearini G, Carrier L. Gene therapy strategies in the treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Physiol. 2019;471(5):807–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-018-2173-5.

Girolami F, Ho CY, Semsarian C, et al. Clinical features and outcome of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy associated with triple sarcomere protein gene mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(14):1444–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.062.

Naso MF, Tomkowicz B, Perry WL, et al. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector for gene therapy. BioDrugs. 2017;31(4):317–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5.

Mearini G, Stimpel D, Geertz B, et al. Mybpc3 gene therapy for neonatal cardiomyopathy enables longterm disease prevention in mice. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):5515. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6515.

Monteiro da Rocha A, Guerrero-Serna G, Helms A, et al. Deficient cMyBP-C protein expression during cardiomyocyte differentiation underlies human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy cellular phenotypes in disease specific human ES cell derived cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;99(1):197–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.09.004.

Prondzynski M, Kramer E, Laufer SD, et al. Evaluation of MYBPC3 trans-splicing and gene replacement as therapeutic options in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2017;7(1):475–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2017.05.008.

Pelliccia F, Pasceri V, Limongelli G, et al. Long-term outcome of nonobstructive versus obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2017;243:379–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.06.071.

Lu D, Pozios I, Hailesalassie B, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with nonobstructive, labile, and obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JAHA. 2018;7(5): e006657. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.006657.

Tremaine L, Al-Fayoumi S, Wetering J, et al. A clinical drug-drug interaction study of Imb-1018972, a novel investigational cardiac mitotrope in phase 2 development for the treatment of myocardial ischemia and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2021;144(1):A10372.

Ho C, Mealiffe M, Bach R, et al. Evaluation of mavacamten in symptomatic patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(21):2649–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.064.

A Multi-Center, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Dose-finding Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of CK-3773274 in Adults With Symptomatic Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (REDWOOD -HCM). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04219826. Updated March 21, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04219826.

Empagliflozin in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (EMPA-REPAIR). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05182658. Updated April 12, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05182658?recrs=ab&cond=Hypertrophic+Cardiomyopathy&draw=3&rank=16.

Clinical and Genetic Determinants of Disease Progression and Response to Sacubitril/Valsartan vs Lifestyle (Physical Activity and Dietary Nitrate) in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03832660. Updated September 29, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03832660?recrs=ab&cond=Hypertrophic+Cardiomyopathy&draw=2&rank=9.

Non-Invasive Radiation Ablation for Septal Reduction in Patients With Hypertrophic Obstructive CardioMyopathy: First in Man Pilot Study. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04153162. Updated November 6, 2019. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04153162?recrs=ab&cond=Hypertrophic+Cardiomyopathy&draw=3&rank=17.

Acknowledgements

Funding

N.R. is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number KL2TR001879. A.T.O. is supported by the Winkelman Family Fund for Innovation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Elizabeth Packard: concept and design, drafting manuscript; Alejandro de Feria: concept and design, drafting manuscript; Supriya Peshin: concept and design, drafting figure; Nosheen Reza: concept and design, drafting figure, critical revision; Anjali Tiku Owens: concept and design, critical revision, supervision and funding. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Elizabeth Packard has nothing to disclose. Alejandro de Feria has nothing to disclose. Supriya Peshin has nothing to disclose. Nosheen Reza reports speaking honoraria from Zoll. Anjali Tiku Owens reports consulting for Cytokinetics, Pfizer, Renovacor and Myokardia/Bristol Myers Squibb and has received research support from Cytokinetics, Myokardia/Bristol Myers Squibb, and Pfizer.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Packard, E., de Feria, A., Peshin, S. et al. Contemporary Therapies and Future Directions in the Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Cardiol Ther 11, 491–507 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-022-00283-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-022-00283-5