Abstract

Introduction

Hospitalization is the largest component of health care spending in the United States. Most hospitalized patients first visit the emergency department (ED), where hospitalization decisions are made. Optimal utilization of hospital resources is critical for all stakeholders.

Methods

We performed a population-based, cross-sectional study evaluating ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and chest pain (CP) suggestive of CAD from 2006 to 2013 using the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample database weighted for national estimates. We analyzed trends using a generalized linear regression model with a Poisson distribution and Wald test.

Results

From 2006 to 2013, there was a 15% decrease in ED visits for CAD (p < 0.01), while ED visit rates for CP increased 31% (p < 0.01). Subsequent inpatient admission rates decreased 18% for CAD (p < 0.01) and 33% for CP (p < 0.01). Trends were not modified by patient and hospital strata.

Conclusion

ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions resulting from CAD decreased from 2006 to 2013. Patients with CP had a substantially higher number of ED visits, with a significant decline in inpatient admissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Hospitalization accounts for one-third of health care spending in the United States, and identifying trends and tools to reduce avoidable incident and readmission hospitalizations is a key objective of value-based care models. |

Cardiovascular conditions are frequent diagnoses associated with hospital admission following visits to the emergency department (ED). |

This study evaluated trends in ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and the symptom of chest pain suggestive of CAD. |

What was learned from the study? |

ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions for CAD decreased between 2006 and 2013. |

The number of ED visits increased over time for patients with chest pain suggestive of CAD, but subsequent inpatient admissions declined over this same period of time. |

These trends may be explained, in part, by changes in health care policy and disease management strategies, including formulation of treatment plans and the use of observation units for patient care. |

Introduction

Acute-care hospitalization is the largest component of health care spending in the United States (US), accounting for ~ 33% of all health care expenditures in 2017, totaling $1.1 trillion [1]. Most hospitalized patients are first seen in the emergency department (ED), where emergency physicians decide whether hospitalization is indicated [2]. Reducing avoidable hospitalizations can be an important step toward decreasing costs while maintaining quality of care. Along these lines, the US health care landscape has been shifting toward value-based models that incentivize quality and penalize poor outcomes, such as excessive hospital readmissions, through a number of alternative payment structures and pay-for-performance measures [3]. However, while quality initiatives can help reduce the rate of hospital readmissions, the net cost of programs varies, and some programs may not provide cost savings [4].

Hospital readmissions that occur soon after discharge are thought to reflect the quality of care transitions from the hospital to outpatient setting [5]. In 2012, the US government mandated a program to reduce the number of hospital readmissions by stipulating that readmissions for a qualifying condition/procedure within 30 days of the initial discharge would lead to reduced payments from Medicare and Medicaid [6, 7]. Outpatient care and observation units are being used more frequently to extend the window for further diagnostic and therapeutic interventions for patients following an ED visit rather than admission or readmission for inpatient care, which has resulted in a declining number of inpatient hospital stays [8]. However, increased use of observation units only partially explains the recent decline in inpatient admissions among Medicare beneficiaries [9].

As of 2014, 60% of adults in the US had a chronic disease and 42% had two or more chronic diseases [10]. Patients with chronic conditions tend to have more ED visits, more inpatient stays, and higher health care spending than patients with no chronic conditions [10]. For patients with chronic diseases, integrated care strategies, such as coordination of care across health and/or social care settings, may reduce the use of health care resources [11]. Cardiovascular disease is one of the most common chronic conditions in the US, affecting an estimated 100 million people in 2015 [12, 13]. Medical costs for managing cardiovascular disease exceed $300 billion each year, with the majority of these costs attributable to hospitalization [12]. In particular, coronary artery disease (CAD) is among the most frequently admitted conditions following ED visits; approximately 80% of ED visits for coronary atherosclerosis and other heart disease were found to result in hospital admission, compared with ~ 20% for all conditions combined [14]. Observation units may play a growing role in cardiovascular care for patients seen in the ED; for example, in 2008, chest pain was the most frequent reason for an ED visit resulting in observation unit care, and accounted for nearly 20% of visits to those units [15]. In light of the aging population and longer life expectancy, the prevalence of CAD is expected to increase substantially over the next 20 years, which will place a growing burden on the health care system. The changing health care and disease management landscapes could also impact overall health care resource use.

In addition to better disease management, it is important to understand the trends in CAD care to identify potential strategies to offset resource utilization and lower costs. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to better understand trends in ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions for patients with CAD and the related symptom of chest pain (CP) suggestive of CAD.

Methods

Analysis Set

We used the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS) for our analysis. The NEDS database is sponsored by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in the US (http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/) [16]. Data records are de-identified for public use and are protected through data use agreements.

The NEDS is composed of 30 million ED visits at more than 900 hospitals, representing a sample of approximately 20% of the data from all US hospital-based EDs, and includes individuals covered by Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurance, as well as those who are uninsured. The sample is selected per the strata of geographic region, trauma center designation, urban/rural location, and hospital ownership/control [17]. Weights are available to reflect national estimates pertaining to 135 million ED visits in 2013. Drawn from statewide data, the NEDS provides ED visits that may or may not have resulted in hospital admission. This database contains several types of information that are useful for research applications, including geographic, hospital, and patient characteristics, and the nature of visits. The NEDS designates patients as inpatient or outpatient after ED care, but does not distinguish whether outpatients were discharged home or receive hospital-based outpatient care in observation status, such as in an observation unit.

Study Population

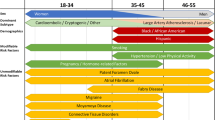

This population-based, cross-sectional study assessed US ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions for patients with CAD and CP from 2006 through 2013. We defined CAD by the primary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes 410 to 414. We defined CP by a primary diagnosis code of 786.5, with CAD as a secondary diagnosis, but no diagnosis for other serious conditions (e.g., aortic dissection) that might also be linked to the symptom and influence the decision to hospitalize. We did not use the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis codes, as they were adopted by the NEDS subsequent to our study end date.

Statistical Methods

We categorized patients with clinical and symptomatic conditions according to patient demographics and hospital characteristics for the years 2006, 2010, and 2013. Our outcome measures included the annual number of ED visits and the annual number of subsequent inpatient admissions at the encounter level that reflect national estimates from 2006 to 2013. We performed a trend analysis for ED visits and subsequent admissions over time using a generalized linear regression model with a Poisson distribution and a Wald test. We also calculated a Quan–Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) based on secondary discharge diagnoses [18].

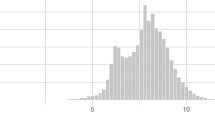

We evaluated variation in subsequent admission rates using a hospital-based risk-standardized admission ratio (RSAR), which was calculated as the ratio of the number of predicted admissions to the number of expected admissions at a given hospital for each clinical outcome or symptom (i.e., 75th over 25th percentile hospitals). In this analysis, we estimated the RSAR for each hospital using a generalized linear mixed model that accounted for correlations among hospital encounters. We adjusted the analytical model for age, sex, household income, insurance status, and patient comorbidities. We also determined the coefficient of variation as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean.

Compliance with Ethic Guidelines

Our study is based on de-identified data collected from a publicly available health care database and does not contain any experimental data with human or animal participants; our analysis was deemed exempt from institutional review board oversight, and we did not obtain informed consent.

Results

Summary Statistics for Distribution of Patient and Hospital Characteristics in Patients with CAD

Characteristics and distribution by respective characteristics were generally similar among patients with CAD for ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions over the three selected years (2006, 2010, and 2013; Table 1). Mean subject age was 66 years, and approximately 60% of patients were male. More than half of the population had Medicare as their primary payer, which is consistent with the age range of this population. The percentage of patients with ED visits was inversely related to household income, with numerically higher numbers of ED visits among patients from low-income households. Most patients with CAD with ED visits were subsequently admitted as inpatients (87.1%, 86.8%, and 83.7% in 2006, 2010, and 2013, respectively), with a similar average length of stay over time (4.2, 4.0, and 4.0 days, respectively; Table 2). CCI scores increased over time for both ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions. No substantial changes were observed for other encounters or hospital characteristics.

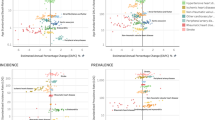

Trend Analysis of ED Visits and Subsequent Inpatient Admissions for Patients with CAD

We have assessed the trend of ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions among patients with CAD from 2006 to 2013. ED visits for patients with a primary discharge diagnosis of CAD decreased by 15% (11.5 vs. 9.8 × 105) visits, respectively; p < 0.01) and the number of subsequent inpatient admissions for CAD decreased by 18% (10.1 vs. 8.2 × 105 admissions, respectively; p < 0.01; Fig. 1a).

Summary Statistics for Distribution of Patient and Hospital Characteristics in Patients with CP

Characteristics and distribution by respective characteristics were generally similar among patients with CP for ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions over the three selected years (2006, 2010, and 2013; Table 3). Mean subject age was 63 years, and approximately 60% of patients were male. Medicare was the most common primary payer for both ED visits and inpatient admissions, and the proportion of ED visits covered by Medicaid increased over time. ED visits were inversely related to household income, with numerically higher percentages of ED visits among patients from low-income households. We observed a numerical increase in CCI score over time for both ED visits and admissions (Tables 3 and 4). There were no substantial changes observed for other encounter or hospital characteristics.

Trend Analysis of ED Visits and Subsequent Inpatient Admissions for Patients with CP

When assessing the trend of ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions among patients with CAD from 2006 to 2013, we found that ED visits for CP increased by 31% (5.9 vs. 7.7 × 105 visits, respectively; unadjusted p < 0.01), while subsequent inpatient admissions decreased by 33% (2.7–1.8 × 105 admissions, respectively; unadjusted p < 0.01; Fig. 1b).

Hospital-based RSAR

We calculated hospital-based RSAR for hospitals that had ≥ 25 ED visits for each condition. A total of 799 and 761 hospitals met this criterion for CAD and CP, respectively (Fig. 2). For CAD, we observed a RSAR of 1.15 for the 75th over 25th percentile hospitals, and the coefficient of variation was 0.15. For CP, we observed an RSAR of 2.47 for 75th over 25th percentile hospitals, with a coefficient of variation of 0.63.

Discussion

Data from the NEDS showed that ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions resulting from CAD decreased linearly from 2006 through 2013. ED visits in patients with CP increased over time, yet subsequent inpatient admissions for these patients decreased significantly. Variation in ED admission rates among studied hospitals was small for patients with a primary diagnosis of CAD. In contrast, there was substantial hospital-level variation in the use of inpatient care for patients presenting to the ED with CP.

These trends in ED visits and subsequent inpatient admissions for cardiovascular conditions may be impacted, in part, by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) legislation, which was signed in 2010 to expand health care coverage for more Americans and to lower health care costs [19]. In the current study, there was a consistent numerical trend for increased ED visits for CAD and CP for patients with lower income, suggesting that despite its intentions, the ACA may not have eliminated health care access challenges. The NEDS data showed that between 2006 and 2013, ED visits for CP increased, but inpatient admissions for CP decreased. Of note, inpatient admissions for CP decreased less for lower-income patients than for higher-income patients, suggesting that outpatient care may be considered less safe for low-income patients. A separate study showed a similar trend of overall decreased inpatient admissions for CP between 2006 and 2012 [20].

The increase in ED visits for CP may also be linked to a lack of programs for disease management education or support, as well as patients’ comfort with performing self-care and notifying their health care teams of exacerbation of symptoms once they have been discharged [21]. Among patients with cardiovascular disease, those who have better communication with their health care provider have fewer ED visits and hospitalizations, and lower annual out-of-pocket costs [22]. Although disease management through clinical care is provided through Medicaid and Medicare, these services are not available to all patients. The decision to implement Medicaid care management programs is made on a state-by-state basis, and, as of 2008, only half of states had done so [23]. Disease management through Medicare Part B consists of clinical care management but not patient self-management. In addition, eligibility to participate is currently limited to patients with two or more chronic conditions that are at more severe stages [24].

Another possible explanation for these observations is the relative ease of formulating a treatment plan for patients who present to the ED with diagnosed CAD, which may reduce the need for hospitalization. It is especially helpful when physicians have access to patient data via electronic health records to inform these decisions in the ED [25, 26]. Patients who present to the ED with nonspecific cardiovascular symptoms like CP receive comprehensive cardiac evaluations that can include an electrocardiogram, physical examination, and cardiac biomarkers, all of which can be performed within the time frame of an ED visit [27]. Using these results, physicians can perform risk stratification, such as a calculation of a HEART (History, ECG, Age, Risk factors, and Troponin) risk score, a measure designed to predict whether patients who present in the ED with CP are at high risk of an adverse event [28]. Increased use of the HEART score, which was introduced in 2008, may explain some of the decrease in inpatient admissions for CP seen in this study.

The declining rate of inpatient admissions over time may also be linked to greater use of observation status, which is billed as an outpatient service even though patients are often treated in the same medical wards, have similar medical needs, and receive similar clinical services as patients who are hospitalized as short-stay inpatients [5]. Between 2009 and 2011, the proportion of Medicare patients with CP who were initially admitted as inpatients decreased, while the proportion who were first admitted to the ED remained steady; during this time, an increasing proportion of Medicare patients with CP were designated as observation status [29]. Observation units are dedicated areas in the hospital where patients in observation status are housed. The shift to observation units allows physicians to maintain oversight of patient care in a lower cost environment by housing patients in one location and using condition-specific protocols to reduce unwarranted variations in care, which could provide major cost savings, and reflects the value-based environment of the current health care landscape in the US [30].

Hospital admission rates can vary for a number of reasons, including patient- and hospital-specific factors such as differences in geographic location, level of ED training, hospital teaching status, local expectations of staff physicians, payment variation, and hospital type; however, even when adjusting for these characteristics, some variations in hospital admission rates have been observed [31, 32]. In this study, the variation in hospital-based RSARs for CAD were low, which may suggest that hospitals are comfortable following established protocols for patients with a known history of CAD. In contrast, there was significant variation in hospital-based RSARs for CP, as might be expected given its potential association with a variety of conditions. More data are needed on the association between nonspecific symptoms such as CP in order to develop recommendations for reducing the hospital-based variability in inpatient admissions for patients presenting with these symptoms.

Emerging technologies like the currently available Patient Activation Model can be used to predict which patients are at risk of avoidable hospitalization [33]. In the future, additional technologies such as artificial intelligence and predictive analytics will be used to predict diagnoses and identify patients at high risk of other costly complications, including prolonged hospitalization, readmission, and mortality [34, 35]. The use of technology to identify patients with a high risk of costly outcomes will help physicians and other decision makers focus appropriate time and resources on preventing outcomes in these patients that may not be immediately apparent from their health records, such as providing additional information and follow-up care to prevent hospital readmissions.

Moving forward, efforts to increase access to disease management education and support at the primary care level may reduce the trend of increased ED visits for certain symptoms. Future research is warranted to examine possible reasons underlying the different ED admission rates between hospitals for symptoms associated with major diseases, such as CAD. These include the expansion of Medicaid services as part of the implementation of the ACA, and the growing presence and potential increased utilization of urgent care clinics.

The current study has several limitations. First, there may be coding bias, misclassification of diagnosis codes, variation in the use of diagnosis codes, and similar issues in this type of database. ICD-10-CM codes, introduced in 2015, were not available at the time of this study, so future studies of ED admission rates for diseases like CAD may be able to provide more detailed information, though there is likely to be an increased risk for coding bias. Also, the NEDS database captured data at the encounter level rather than at the patient level; therefore, multiple visits by the same patient cannot be identified. The NEDS also does not distinguish between patients who are immediately discharged to their homes and those who are managed in the hospital under observation status before being discharged, and does not contain the clinical information necessary to assess the cause of subsequent hospitalization. Lastly, the trend test was conducted without adjusting for potential confounding factors.

Conclusions

Based on data from the NEDS from 2006 to 2013, the number of ED visits and admissions for CAD decreased over time, and there was a trend for increased number of ED visits and decreased number of subsequent inpatient admissions over time for patients with CP. Adoption of new clinical tools and policy changes during the study period may have influenced disposition decisions, and subsequent study is warranted to investigate whether admission rates also fell for similar conditions during the study time frame.

References

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2017 highlights. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed 18 Dec 2019.

Weiss AJ, Wier LM, Stocks C, Blanchard J. Overview of emergency department visits in the United States, 2011. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb174-Emergency-Department-Visits-Overview.jsp. Accessed 18 Dec 2019.

Srinivasan D, Desai NR. The impact of the transition from volume to value on heart failure care: implications of novel payment models and quality improvement initiatives. J Card Fail. 2017;23:615–20.

Nuckols TK, Keeler E, Morton S, et al. Economic evaluation of quality improvement interventions designed to prevent hospital readmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:975–85.

Sabbatini AK, Wright B. Excluding observation stays from readmission rates—what quality measures are missing. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2062–5.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed 20 Feb 2019.

Medicare.gov. Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/readmission-reduction-program.html. Accessed 4 Apr 2019.

Blecker S, Gavin NP, Park H, Ladapo JA, Katz SD. Observation units as substitutes for hospitalization or home discharge. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67(706–13):e2.

MedPAC. Hospital inpatient and outpatient services. In: Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. MedPAC: Washington, DC; 2014; pp. 51–90.

Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple chronic conditions in the United Stateshttps://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/tools/TL200/TL221/RAND_TL221.pdf. Accessed 18 Dec 2019.

Damery S, Flanagan S, Combes G. Does integrated care reduce hospital activity for patients with chronic diseases? An umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011952.

Khavjou O, Phelps D, Leib A. Projections of cardiovascular disease prevalence and costs: 2015–2035. Technical report. 2016. https://healthmetrics.heart.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Projections-of-Cardiovascular-Disease.pdf. Accessed 18 Dec 2019.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. About chronic diseases. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm. Accessed 18 Dec 2019.

Venkatesh AK, Dai Y, Ross JS, Schuur JD, Capp R, Krumholz HM. Variation in US hospital emergency department admission rates by clinical condition. Med Care. 2015;53:237–44.

Venkatesh AK, Geisler BP, Gibson Chambers JJ, Baugh CW, Bohan JS, Schuur JD. Use of observation care in US emergency departments, 2001 to 2008. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24326.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS). https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/. Accessed 18 Dec 2019.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. NEDS description of data elements. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/neds/nedsdde.jsp. Accessed 18 Dec 2019.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–9.

HealthCare.gov. Affordable Care Act (ACA). https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/affordable-care-act/. Accessed 18 Dec 2019.

Yiadom MYAB, Baugh CW, Jenkins CA, et al. Change in care transition practice for patients with nonspecific chest pain after emergency department evaluation 2006 to 2012. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:1527–30.

Stamp KD, Machado MA, Allen NA. Transitional care programs improve outcomes for heart failure patients: an integrative review. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29:140–54.

Okunrintemi V, Spatz ES, Di Capua P, et al. Patient-provider communication and health outcomes among individuals with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States: medical expenditure panel survey 2010 to 2013. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017;10:e003635.

Arora A, Boehm J, Chimento L, Moldawer I, Tsien C. Designing and implementing Medicaid disease and care management programs: a user’s guide. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/medicaidmgmt.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2017.

Medicare.gov. Your Medicare coverage. Chronic care management services. https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/chronic-care-management-services.html. Accessed 15 Oct 2017.

Ben-Assuli O, Leshno M. Assessing electronic health record systems in emergency departments: using a decision analytic Bayesian model. Health Informatics J. 2016;22:712–29.

Ward MJ, Froehle CM, Hart KW, Collins SP, Lindsell CJ. Transient and sustained changes in operational performance, patient evaluation, and medication administration during electronic health record implementation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:320–8.

Yiadom MY. Acute coronary syndrome clinical presentations and diagnostic approaches in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin N Am. 2011;29(689–97):v.

Six AJ, Backus BE, Kelder JC. Chest pain in the emergency room: value of the HEART score. Neth Heart J. 2008;16:191–6.

Cafardi SG, Pines JM, Deb P, Powers CA, Shrank WH. Increased observation services in Medicare beneficiaries with chest pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:16–9.

Baugh CW, Venkatesh AK, Hilton JA, Samuel PA, Schuur JD, Bohan JS. Making greater use of dedicated hospital observation units for many short-stay patients could save $3.1 billion a year. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:2314–23.

Capp R, Ross JS, Fox JP, et al. Hospital variation in risk-standardized hospital admission rates from US EDs among adults. Am J Emerg Med. 2014;32:837–43.

Cotterill PG, Deb P, Shrank WH, Pines JM. Variation in chest pain emergency department admission rates and acute myocardial infarction and death within 30 days in the Medicare population. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:955–64.

Hibbard J, Greene J, Sacks RM, Overton V. Improving population health management strategies: identifying patients who are more likely to be users of avoidable costly care and those more likely to develop a new chronic disease. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/journal-article/2016/aug/improving-population-health-management-strategies-identifying. Accessed 18 Dec 2019.

Rajkomar A, Oren E, Chen K, et al. Scalable and accurate deep learning with electronic health records. NPJ Digit Med. 2018;1:18.

Khurana HS, Groves RH Jr, Simons MP, et al. Real-time automated sampling of electronic medical records predicts hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2016;129(688–98):e2.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC (Titusville, NJ, USA), which also funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee. Medical writing was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing support was provided by Dana Tabor, PhD, of MedErgy (Yardley, PA, USA).

Authorship Contributions

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. CE, AP, ZD, CDP, JHL, and CWB were involved in study design. CE, AP, ZD, CDP, JHL, and CWB were involved in the interpretation of the results. ZD and JHL were responsible for the statistical analyses.

Prior Presentation

A portion of these results were originally presented at the Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research (QCOR) Scientific Sessions on April 3, 2017, in Arlington, VA and at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) on May 19, 2017, in Orlando, FL.

Disclosures

CE, AP, ZD, CDP, and JHL are employees of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC (a Johnson & Johnson company) and hold stock in Johnson & Johnson. CWB has worked as a consultant and advisory board member for Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Salix Pharmaceuticals, has previously received research funding from Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Boehringer Ingelheim, and has also served as an advisory board member and as a paid speaker for Roche Diagnostics.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Our study is based on de-identified data collected from a publicly available health care database and does not contain any experimental data with human or animal participants; our analysis was deemed exempt from institutional review board oversight, and we did not obtain informed consent.

Data Availability

The NEDS data analyzed during the current study are available at the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website (https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/news/exhibit_booth/neds_brochure.jsp). The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11861097.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eichelberger, C., Patel, A., Ding, Z. et al. Emergency Department Visits and Subsequent Hospital Admission Trends for Patients with Chest Pain and a History of Coronary Artery Disease. Cardiol Ther 9, 153–165 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-020-00168-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-020-00168-5