Abstract

We have studied the consequence of different functionalization types onto the decoration of multi-wall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) surface by nanoparticles of bismuth and nickel oxides. Three organic molecules were considered for the functionalization: 5-amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid, 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid and sulfanilic acid. Nanotubes modification with in situ created diazonium salts followed by their impregnation with suitable salts [ammonium bismuth citrate and nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate] utilizing infrared (IR) irradiation was found the crucial stage in the homogeneous impregnation of functionalized CNTs. Furthermore, calcination of these samples in argon environment gave rise to controlled decorated MWCNTs. The currently used technique is simple as well as effective. The synthesized materials were characterized by XPS, PXRD, FESEM, EDX, HRTEM and Raman spectroscopy. Bismuth oxide decorations were successfully performed using 5-amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid (particle size ranges from 1 to 10 nm with mean diameter ~ 2.4 nm) and 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid (particle size ranges from 1 to 6 nm with mean diameter ~ 1.9 nm) functionalized MWCNTs. However, only 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid functionalized MWCNTs showed strong affinity towards oxides of nickel nanoparticles (mainly in hydroxide form, particles size ranging from 1 to 6 nm with mean diameter ~ 2.3 nm). Thus, various functions arranged in the order of their increasing anchoring capacities are as follows: sulfonic < carboxylic < phosphonic. The method is valid for large-scale preparations. These advanced nanocomposites are potential candidates for various applications in nanotechnology.

Graphic abstract

Article highlights

-

Simple and effective method for the decoration of MWCNTs with nanoparticles of Bi and Ni oxides.

-

5-amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid, 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid and sulfanilic acid were considered for the functionalization.

-

Various functions arranged in the order of their increasing anchoring capacities are as follows: sulfonic < carboxylic < phosphonic.

-

The method is valid for large-scale preparations.

-

Potential candidates for various applications in nanotechnology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [1] are one of the great carbonaceous nanomaterial displaying interesting properties such as high aspect ratio (~ 1000), remarkable tensile strength, chemical stability, huge surface area, notable electrical and thermal properties. Such properties are linked to their functionalities, structure and morphology [2] which make CNTs potential candidates for different applications such as in tissue engineering [3], solar and fuel cells, hydrogen storage and generation [4], supercapacitors, lithium ion batteries, field emission sources and electrochemical sensors [5], to cite a few. CNTs are usually categorized into single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and multi-wall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) [6]. Double-wall CNTs also exist and have been even diazotized for further surface modification [7].

Most of the as-synthesized CNTs powders contain not only CNTs, but also other carbonaceous impurities (amorphous carbon, nanocrystalline graphite and fullerenes), metallic catalysts and support (silica and alumina) [8,9,10]. These impurities are detrimental to CNTs application performances. To avoid this problem, impurities should be first removed without destroying the CNTs structure [11]. In the literature, chemical oxidation has been widely utilized to purify as-prepared CNTs. It comprises gas phase (utilizing O2, Cl2, H2O, air, etc.), electrochemical as well as liquid-phase oxidation (involving acid treatment, etc.). The usual oxidants in liquid-phase oxidation are H2O2, H2SO4, HNO3, HCl and KMnO4 have disadvantages: CNTs cutting, CNTs extremities opening and formation of undesired products on the CNTs surface [12]. Most of these limitations are avoided using a basic treatment [13].

To extend the range of their applications, CNTs are often decorated with various metals [14], metal oxides [15] and semiconducting nanoparticles [16] to improve their electric, optical and magnetic properties [17,18,19].

The nanoscale dimension (size < 10–20 nm) of these metals or metal oxides particles confers unique magnetic, chemical and optical properties, but they decrease with the particle size and mainly disappear beyond 40–50 nm [20]. Nanoparticles provide large surface area for adsorption [21], increase sensitivity for molecule detection [22], tune magnetic [23] and optical properties [24]. For example, bismuth can change from a semi-metal to a semi-conductor which makes it very interesting among nanosized materials [25, 26]. Due to its large band gap (2.4–3.96 eV) [27], bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) exhibits high dielectric permittivity, photoluminescence, oxide ion conductivity, high refractive index and photocatalytic activity. This makes it one of the most useful materials in nanotechnologies. It has various applications such as in the biomedical field [28], superconductors [29], fuel cells, sensors, catalysis [27], etc. Bi2O3 exists in five polymorphs: α (monoclinic), β (tetragonal), γ (bcc), δ (fcc) and ε (triclinic) [30]. α form is stable at low temperature (room temperature) and it changes into δ phase through heating at a higher temperature (729 °C), but comparatively other forms (β, γ and ε forms) are metastable. α-Bi2O3, β-Bi2O3 and δ-Bi2O3 forms display photocatalytic activity, but the more active heterogeneous photocatalyst is β-Bi2O3 [31, 32].

Nickel nanoparticles are used in numerous fields [33] due to their catalytic, magnetic and tribological properties [34]. Furthermore, compounds based on nickel exhibit high electrochemical performances [35]. For example, among the various transition metal oxides/hydroxides pseudo-capacitive materials, nickel hydroxide is a striking candidate in high-performance supercapacitors due to the fact that it shows excellent chemical stability, high specific capacitance, easy preparation (cost effective), distinct redox activity, layered structure and various morphologies [36]. However, the low life cycle of pseudo-capacitive Ni(OH)2 and its poor electrical conductivity limit their practical applications [37]. This problem can be solved by combining with conductive additives such as graphene, carbon nanotubes, etc.

Various methods have been reported for MWCNTs decoration with nickel or nickel oxide/hydroxide nanoparticles, but only a few with bismuth or bismuth oxide nanoparticles [5, 16, 38]. The control of the dispersion, agglomeration and uniformity is not yet completely resolved.

To avoid these limitations, optimizations are needed at all steps of elaboration of the nanoparticles: (a) type of functionalization method and the structure of grafting molecules, (b) use of different salts or classical/IR heating during impregnation [39], and (c) time and temperature of calcination [40].

CNTs functionalization is a key step towards their decoration with metal or metal oxides nanoparticles. It can be performed with aryl diazonium salts grafting which is an efficient method to modify various surfaces with different compounds including nanoparticles [41,42,43].

Among different aryl diazonium salts, the ones containing carboxylic, phosphonic and sulphonic group are very interesting for CNTs functionalizations, because they contain highly acidic groups and their deprotonation leads to negatively charged ions which interact with positively charged metal ions and favor the so-called impregnation. Thus, their comparison in terms of anchoring affinity is of interest. 5-amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid, 4-aminobenzylphosphonic and sulfanilic acids have been chosen in this comparative study due to their cost, industrial availability and their potentials in future applications. The ions concentration on the CNTs surfaces together with their complexation ability with the acidic function strongly influences the quality of the generated nanoparticles.

The impregnation via IR irradiation leads to tiny nanocrystals evenly anchored on CNTs surface [11]. This IR effect is due to the photo-absorption and thermal properties of CNTs. Their ability to absorb IR irradiation, and promptly transferring the electronic excitations to molecular vibration energies, produces heat and activates the chemical processes [39]. Without IR irradiation, agglomerated particles tend to form with a very poor anchorage to the CNTs surfaces.

The present work focuses on the effect of chemical functionalization (carboxylic, phosphonic and sulphonic groups) of MWCNTs on the quality of bismuth and nickel nanoparticles: size, morphology, nature, distribution and anchorage on the MWCNTs surface (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Chemicals

5-Amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid (97%), ammonium bismuth citrate (≥ 99%) (ABC), nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate (NNH), 4-aminobenzenesulfonic acid (> 98.0) and 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid (97 + %) were got from abcr GmbH, Sigma-Aldrich, Vel s.a., ACS and Prime Organics Inc., respectively. NaNO2 (99.2%), HClO4 (70%), acetone (> 99%), NaOH (≥ 98%) and pentane (99%) were received from Fisher-Scientific, Merck, Chem Lab, ACS Reagent and Lab Scan Analytical Sciences, respectively. All these chemicals were used without further purification.

Nanocyl SA (Belgium) MWCNTs (NC 7000) (> 95%, average diameter = 10 nm, length = 0.1–10 μm) were used after purification (Section “MWCNTs purification and functionalization”). Milli-Q water (18.2 MΩ cm) was used in all experiments.

Apparatus

Functionalization and impregnation were performed under IR irradiation utilizing a Petra IR 11 lamp (voltage: 230 V and capacity: 150 W). PAN analytical diffractometer was used to perform X-Ray powder diffraction (XRD) studies. It was maintained at tube current: 30 mA and operating voltage: 45 kV with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418Å). Thermo Scientific K-Alpha X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS) with a hemispherical analyzer and a monochromatized Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV) was used. The most intense peak of the core level was calibrated with respect to the C1s component (set at 284.6 eV). Tecnai 10 Philips microscope was used to carry out transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses. Their samples preparation steps comprise dispersion in ethanol and then drop casting onto grid (carbon coated copper). This instrument was handled at emission current: 5 µA and accelerating voltage: 80 kV with spot size: 3. HR-TEM, Tecnai G2 was functioned at emission current: 5.77 µA, accelerating voltage: 200 kV and spot size − 1. FESEM is realized via JEOL JSM-7500F microscope. It is equipped with EDX and worked at accelerating voltage: 15 kV and emission current: 20 µA (working distance: 8 mm). Raman studies were performed using ST-BX51E Raman optical microscope. Conditions include excitation laser: Ar 514.5, exposure time: 5 s, number of accumulations: 10, number of kinetics: 1, laser power: 100 MW and software: STR (Raman).

Synthesis of the nanocomposites

MWCNTs purification and functionalization

The MWCNTs purification [13, 20] and their functionalization using 5-amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid were carried out according to our previously method [20]. To get purified MWCNTs (p-MWCNTs), a mixture of crude MWCNTs (1 g) and 12 M NaOH (100 ml) solution was refluxed at 170 °C for 12 h. Furthermore, thinned with water, filtered, flushed with water and then with acetone and finally dried. For functionalization with 5-amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid (p-MWCNTs-D3), a mixture of purified MWCNTs (80 mg), 5-amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid (150 mg), H2O (10 ml), NaNO2 (46 mg) and HClO4 (69 µl,) was IR irradiated for 1 h under constant magnetic stirring. Then, it was filtered, washed with pentane and then with acetone and lastly dried. The same procedure was used to functionalize p-MWCNTs with 4-aminobenzylphosphonic (125 mg) and sulfanilic (115 mg) acids. These are referred to as p-MWCNTs-CH2P1 and p-MWCNTs-S1, respectively.

Impregnation on functionalized MWCNTs

Ammonium bismuth citrate, ABC 1.875 g (0.01 M) was dissolved in 100 ml water. Then, p-MWCNTs-D3 was added to this solution. The mixture was subjected to sonication (5 min) and then IR irradiated (2 h.) under constant agitation. Afterward, it was filtered, washed with water and then acetone and finally dried. This sample is known as p-MWCNTs-D3/ABC. The other functionalized nanotubes (p-MWCNTs-S1 and p-MWCNTs-CH2P1) were impregnated using the same procedure and marked as p-MWCNTs-S1/ABC and p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/ABC, correspondingly. On the same basis, 0.291 g (0.01 M) nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate (NNH) was used in the formation of p-MWCNTs-D3/NNH, p-MWCNTs-S1/NNH and p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/NNH.

Calcination of impregnated MWCNTs

The calcinations of the impregnated samples were carried out in a furnace furnished with a quartz tube. p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/NNH were calcined at 400 °C for 2 h in a continuous argon gas environment lead to p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/ONi. To avoid the problem of bismuth metal evaporation during heating, p-MWCNTs-D3/ABC and p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/ABC were first calcined at 250 °C for 30 min in air to convert bismuth to bismuth oxide (bismuth oxide having a higher melting point than bismuth) and further heated in an argon gas environment at 350 °C for 30 min to form p-MWCNTs-D3/OBi and p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/OBi, respectively.

Results and discussion

At the different steps of their elaboration, the synthesized materials have been characterized by XPS, PXRD, FESEM, EDX, HRTEM and Raman spectroscopy.

Crystal structure study by PXRD

PXRD analysis gave data about the crystal structure of nanoparticles (Fig. 2). The nature of particles is discussed in the next paragraph. In all cases, the peak found at 2θ = 25.89° is allocated to (002) plane of graphitic carbon. The reflections from (100), (004) and (110) plane of MWCNTs are related to the peaks at 2θ = 42.65°, 53.19 and 77.89°, respectively [44]. Some of these peaks are not prominent in some samples (p-MWCNTs-D3/OBi and p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/OBi).

In the case of p-MWCNTs-D3/OBi samples (Fig. 2b), the other peaks are allocated to Bi2O3 NPs. These peaks are present at 2θ = 16.21° (110), 22.96° (020), 27.96° (021), 30.26° (121), 31.81° (002), 32.68° (220), 41.29° (122), 41.97° (230), 45.17° (231), 46.25° (222), 46.91° (040), 48.42° (140), 51.31° (141), 54.34° (023), 55.50° (241), 57.74° (042), 59.11° (142), 62.12° (341), 63.38° (151), 66.34° (004), 68.50° (440), 72.95° (351), 74.43° (243), 75.58° (061), 76.01° (224), 77.46° (442), 78.03° (260), 85.12° (044) and 86.70° (262) (Reference code: 98-005-2732) [16]. Their sharp and resolved structure is indicative of the well-crystallized nature of Bi2O3 NPs. The peak intensity and position also points to the formation of the tetragonal Bi2O3 β-phase {space group: P-421c, space group number: 114, a(Å) = 7.7430, b(Å) = 7.7430, c(Å) = 5.6310 and α = β = γ = 90°}. PXRD patterns of p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/OBi (Fig. 2c) also prove that bismuth is in Bi2O3 form (β-phase) and crystalline. On the contrary, the nickel hydroxide nanoparticles on p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/ONi are highly amorphous as no well-resolved PXRD peaks are observed (Fig. 2d). It is found from the literature that it is in α-Ni(OH)2 form [45]. There is a change in the peak intensity at 25.89° in the XRD pattern (Fig. 2b, c). This is related to the amount of Bi2O3 on the CNTs surface. Increased concentration effects CNTs structures to a large extent which is why the peak at (002) is less intense in p-MWCNTs-D3/OBi than in p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/OBi. It is reported in the literature that the increase in the loading of particles causes a significant decrease in the peak intensity of CNTs especially the one at 25.89° and the particle peak becomes more intense [46].

Materials morphology by TEM

TEM micrographs of crude MWCNTs, purified MWCNTs and calcined samples are given in Fig. 3. TEM analysis is used to determine the particles sizes and their distribution. Crude MWCNTs (Fig. 3a) contain a large amount of impurities, mainly alumina (Eq. 1) [11], eliminated after the NaOH treatment step (Fig. 3b). This basic treatment carried out at 170 °C has definite advantages over acidic actions which cause significant damages to the nanotubes: MWCNTs cutting and establishment of needless functional groups on the surface. Catalytic chemical vapor deposition method is used by NANOCYL Company to synthesize MWCNTs. The present method does not remove completely the catalyst (transition metal) impurity, but it is not a problem because it is in an insignificant amount as confirmed by TEM and other characterizations. More importantly, NaOH treatment is used to purify MWCNTs as this is non-destructive method.

TEM micrographs display that the bismuth oxide decorations were observed on 5-amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid functionalized MWCNTs (Fig. 3c). The particle size varies from 1 to 10 nm, with a Gaussian mean diameter ~ 2.4 nm (Fig. 4a). In 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid functionalized MWCNTs (Fig. 3d) the particle size ranges from 1 to 6 nm, with a Gaussian mean diameter ~ 1.9 nm (Fig. 4b). However, only 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid functionalized MWCNTs has enough affinity for the oxides of nickel nanoparticles (Fig. 3e), mainly in their hydroxide form. Their particle size ranges from 1 to 6 nm, and Gaussian mean diameter ~ 2.3 nm (Fig. 4c). Thus, the various functions arranged in the order of their increasing anchoring capacities are as follows: sulfonic < carboxylic < phosphonic. This trend can be explained based on the fact that phosphonic has two removable hydrogens, while sulphonic and carboxylic groups have only one. As the functionalized MWCNTs with these groups are dispersed in water, they dissociate to produce negatively charged anion (the more the anions produced, the more is the anchoring affinity) which can attract positively charged metal ions during the impregnation step. So, definitely, we expect the phosphonic group to exhibit a larger anchoring ability. Though carboxylic and sulphonic groups have the same number of replaceable hydrogens, here, we have used tricarboxylic groups to maximize the anchoring ability. The nanoparticles are homogeneously decorating the MWCNTs. No free nanoparticles are observed outside the carbon nanotube surfaces.

Raman characterization of materials

Raman spectroscopy is commonly applied to probe the quality of the carbon nanotubes. In the crude MWCNTs, Raman spectra (Fig. 5a), D band (1341 cm−1) and G band (1571 cm−1) are the main features. D band is a disorder-induced characteristic, mainly accredited to the occurrence of amorphous or disordered carbon structures [47]. There is also a small shoulder peak D′ at around 1610 cm−1 which is allocated to the disordered symmetry of the carbon sp2 network [48]. This peak is more pronounced in p-MWCNTs-D3/OBi. The ID/IG ratio change from 1.03 to 0.87 in the case of Bi2O3 nanoparticles can be related to its amount which influences the lattice of MWCNTs by creating more defects. So more Bi2O3 nanoparticles (p-MWCNTs-D3/OBi) leading to more defect and hence increasing the ID/IG ratio, but when it is the reverse case (p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/OBi), ID/IG is less. Thus, the parameter used to check the quality (level of alteration or imperfections of MWCNTs) is ID/IG ratio. This ratio is 1.19 for crude MWCNTs indicating that it has inherent defects incorporated during their synthesis, but it decreases after the purification (Fig. 5b–e) and decoration steps. This indicates again that the present adopted method conserves the overall integrity of the MWCNTs as well as improves their quality. This is one of the advantages of the present work over other methods which suffer from material quality problems (disorder in the carbon wall) after the modification of CNTs with nanoparticles [49, 50].

Mapping of the materials surface by EDX

Elemental compositions of synthesized materials obtained through EDX are listed in Table 1 and the corresponding spectra are displayed in Fig. 6. EDX mapping images of the crude MWCNTs (Fig. 7a) clearly indicate the presence of Al, Si, and O species originating from the support used in the carbon nanotubes synthesis. They are fully removed after the purification process (Fig. 7b) indicating its effectiveness. Table 1 shows the presence of the characteristic elements in the different samples. They are in line with the XPS data and authorize the success of nanocomposites synthesis.

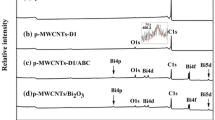

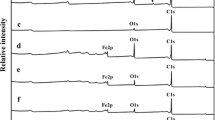

Materials chemical composition by XPS

XPS is used to determine the surface atomic composition of the materials as well as to probe the chemical states of the metallic species. Elemental compositions of the different samples obtained from the XPS analysis are listed in Table 2. The final calcined samples and purified MWCNTs’ survey spectra are given in Fig. 8. Purified MWCNTs exhibit traces of oxygen due to the presence of some residual oxygenated species (C–O). After the functionalization steps, significant enhancement in the oxygen amount was noticed along with the existence of other elements (P or S) characteristic of the acid functions of the aryl diazonium salts used in the functionalizations. Also, nitrogen was evidenced due to the occurrence of azo connection [41, 51] (Fig. 1). Diazonium species (in situ generated in our case from parent aniline) are unstable and leads mainly to –C–C– covalent bond formation and to a lesser extent to C–NN–C covalent bonds (azo connection) on the CNTs. The occurrence of nitrogen in the functionalized sample is confirmed by XPS.

It can be noticed that the nitrogen amount seems to be a function of the nature of the aromatic side groups (Table 2). The above facts clearly indicate the effective modification of the purified MWCNTs by the aryl diazonium salts bearing tricarboxylic, phosphonic or sulphonic acid groups. Effective impregnation with ABC was observed with tricarboxylic and phosphonic groups, while successful impregnation with NNH was observed only with the phosphonic group indicating that it has a higher affinity than the sulphonic group for complexing this metal salt. This is based on the fact that in p-MWCNTs-S1/ABC, Bi is present only in very small quantity, contrary to the other case. So, only p-MWCNTs-D3/ABC and p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/ABC were considered in further experiments. Out of p-MWCNTs-D3/NNH, p-MWCNTs-S1/NNH, and p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/NNH, only p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/NNH was considered as it has the highest amount of Ni. So, along with purified MWCNTs used for comparison, only these three samples were considered and the complete characterizations were provided for their calcined derivatives which are our targeted samples. In the case of p-MWCNTs-S1 (Table 2), sodium is present but disappears after the impregnation. The metals remain in the samples after calcination. Only the effective decorated samples are highlighted in bold (Table 2). As it can be seen in some of the calcined samples, nitrogen is still present but in very low amount, indicating that after calcination, most of the aryl connections disappear.

In the XPS fitting, the most intense peak of the core-level spectra was adjusted with respect to the C1 s level (284.6 eV). Thermo Avantage software is used for XPS peak fitting. Gauss-Lorentz Mix was very useful for C1s asymmetric peak fitting [52]. Indeed, FWHM of the peaks fixed with reasonable range.

C1 s core-level XPS spectra of purified MWCNTs, p-MWCNTs-D3, p-MWCNTs-CH2P1, and p-MWCNTs-S1 are depicted in Fig. 9. The analysis of C1s XPS data of p-MWCNTs-D3 (Fig. 9b) evidences the presence of six peaks [53]. The first peak (right side), broad asymmetric and intense, is a result of sp2-hybridized graphitic carbon occurring at 284.4 eV. Whereas, the peak at 285.4 is accountable for sp3-hybridized character of carbons indicative of structural imperfections on the CNTs. It is very usual to see peculiar line-shape, asymmetrically broadened C1s peak with a very slow decreasing intensity very slowly towards higher binding energy side in carbonaceous materials such as graphites, vitreous carbons, carbon nanotubes, etc. [54]. This is related to its conductive nature. Furthermore, modification with different groups creates defects which also contribute to the C1s peak shape [55]. Thus, the asymmetry factor is related to semi-metal effects happening from conduction band electrons [52]. The peaks corresponding to carbon attached to oxygen single bonds (C–O), carbon attached to oxygen double bonds (C=O) and carbon associated with two oxygen atoms (–COO) occur at 286.3, 287.5 and 289.6 eV, respectively. It is worth to note that C–O C1s peak component in all the samples (Fig. 9), except in p-MWCNTs-D3 (Fig. 9b), is weak and narrow, because p-MWCNTs-D3 contains three carboxylic groups.

Lastly, the aromatic characteristic shake-up peak of CNTs appears at 290.5 eV. While considering p-MWCNTs-CH2P1 and p-MWCNTs-S1, the peaks related to C–P (Fig. 9c) and C–S (Fig. 9d) bounds, respectively, are not clearly detectable, because they appear at similar energies as the sp2 C–C feature [56,57,58,59]. The peaks correspond to P2p (133.7 eV) and S2p (168.5 eV) for p-MWCNTs-CH2P1 and p-MWCNTs-S1, respectively (Fig. 9). These energies indicate that P and S atoms are in an oxidized form. XPS does not provide direct evidence on the carbon–carbon chemical bond between CNTs and added species. However, it does it indirectly by measuring the C–C sp3 component indicative of CNTs external surface structural defects resulting from the covalent functionalization. When comparing the fittings of purified and functionalized MWCNTs, a significant enhancement is observed in the C–C sp3 peak intensity. The major difference is found in the case of the tricarboxylic group (Fig. 9).

XPS high-resolution spectra of metal oxides present in p-MWCNTs-D3/OBi, p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/OBi and p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/ONi are revealed in Fig. 10. In p-MWCNTs-D3/OBi, the Bi 4f spectrum (Fig. 10a) consists of a doublet. The peaks at 159.5 and 164.8 eV, separated by 5.3 eV, are allotted to Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2, respectively. This corresponds to Bi3+ oxidation state of Bi2O3 form [60]. The circumstances are similar for p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/OBi (Fig. 10b) (Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2 at 159.9 and 165.2 eV, respectively). In p-MWCNTs-CH2P1/ONi (Fig. 10c), the peaks position and pattern of the Ni2p spectrum reveal that Ni is mostly in hydroxides form [61].

Reaction pathway

Organic compounds possessing a common functionality R-N2+ X− (where R = alkyl, aryl and X = counter anion) are known as diazonium salts. The key mechanism of diazonium formation is displayed in Fig. 11. Mostly, diazonium salts synthesis is obtained via reaction of aromatic amines and nitrous acids (normally, in situ produced nitrous acid is achieved by treating sodium nitrite with a mineral acid) resulting in a nitrosyl cation (Fig. 11a). Perchloric acid is used in the present case. In this work, the impurities on crude MWCNTs are removed by refluxing them in NaOH aqueous solutions [62]. A simple technique for their functionalization is applied by creating in situ diazonium compounds from their respective parent anilines. The main advantage is that it does not require isolating the diazonium salts after their synthesis. When these react with the carbon surface, they form C–NN–C covalent bonds [41, 51], but diazonium salts mostly undergo dissociation to form aryl cation (hetero-lytic detachment: aryl cation and N2) and aryl radicals (e− donation through a reducing agent, de-diazoniation may occur via homo-lytic disconnection, leading to an unstable aryl radical and N2) [63] which form –C–C– covalent bond after reacting with carbon surface (Fig. 1). Thus, apart from C–NN–C covalent bonds’ formation [64], other possible interface bonds are either CNT-Aryl or an interfacial azoether linkage such as CNT–O–N=N-Aryl. The existence of azoether has been proved in the literature using ToF–SIMS [65, 66]. Furthermore, the latter can undergo dediazonation reaction leading to the formation of CNT-O-Aryl. Eventually, esterification can occur after reaction of carboxylates with diazonium groups followed by dediazonation. It is also possible that the diazonium can be adsorbed and remains attached to COO-groups from CNTs by electrostatic interactions [67]. The diazonium-grafted functions are reacted with the aqueous salt solutions (impregnation step). During this process, the acidic ends loose protons and react with the metallic cations. When IR irradiation is applied, metal precursors (ABC or NNH) are more efficiently impregnated on the MWCNTs surfaces [40]. After calcination, small nanoparticles are formed at the surface of the MWCNTs (Fig. 1).

Conclusions

The different functionalizations (5- amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid, 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid and sulfanilic acid) impact the decorations of MWCNTs with oxides of bismuth and nickel nanoparticles. Crystalline bismuth oxide decorations were successfully achieved using functionalized MWCNTs with 5- amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid (particle size ranging from 1-10 nm, ~ 2.4 nm Gaussian mean diameter) and 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid (particle size ranging from 1 to 6 nm, ~ 1.9 nm Gaussian mean diameter) functionalized MWCNTs. However, only 4-aminobenzylphosphonic acid functionalized MWCNTs showed sufficient affinity towards nickel oxides nanoparticles (mainly in hydroxide form, particle size ranging from 1 to 6 nm and ~ 2.3 nm Gaussian mean diameter). Bismuth oxide nanocrystal decoration on MWCNTs using 5- amino-1,2,3-benzenetricarboxylic acid is considered for the first time. The increasing anchoring abilities of the different functions are as follows: sulfonic < carboxylic < phosphonic. 4-Aminobenzylphosphonic acid has been utilized fruitfully for the first time to decorate MWCNTs with metal oxide nanoparticles (Ni and Bi). Its anchoring capacities make it a promising molecule for yet-to-develop new materials by decorating MWCNTs with other metallic nanoparticles. The present methodology, in addition to its simplicity and effectiveness, is valid for large-scale preparations.

References

Iijima, S.: Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 354, 56–58 (1991)

Bhakta, A.K., Mascarenhas, R.J., D’Souza, O.J., Satpati, A.K., Detriche, S., Mekhalif, Z., Dalhalle, J.: Iron nanoparticles decorated multi-wall carbon nanotubes modified carbon paste electrode as an electrochemical sensor for the simultaneous determination of uric acid in the presence of ascorbic acid, dopamine and l-tyrosine. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 57, 328–337 (2015)

Kouser, R., Vashist, A., Zafaryab, M., Rizvi, M.A., Ahmad, S.: Biocompatible and mechanically robust nanocomposite hydrogels for potential applications in tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 84, 168–179 (2018)

Wang, H., Zhou, H., Zhang, W., Yao, S.: Urea-assisted synthesis of amorphous molybdenum sulfide on P-doped carbon nanotubes for enhanced hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Sci. 53, 8951–8962 (2018)

Erady, V., Mascarenhas, R.J., Satpati, A.K., Bhakta, A.K., Mekhalif, Z., Delhalle, J., Dhason, A.: Carbon paste modified with Bi decorated multi-walled carbon nanotubes and CTAB as a sensitive voltammetric sensor for the detection of Caffeic acid. Microchem. J. 146, 73–82 (2019)

Georgakilas, V., Perman, J.A., Tucek, J., Zboril, R.: Broad family of carbon nanoallotropes: classification, chemistry, and applications of fullerenes, carbon dots, nanotubes, graphene, nanodiamonds, and combined superstructures. Chem. Rev. 115, 4744–4822 (2015)

Joyeux, B.X., Mangiagalli, P., Pinson, J.: Localized attachment of carbon nanotubes in microelectronic structures. Adv. Mater. 21, 4404–4408 (2009)

Farghali, A., Tawab, H.A.A., Moaty, S.A.A., Khaled, R.: Functionalization of acidified multi-walled carbon nanotubes for removal of heavy metals in aqueous solutions. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 7, 101–111 (2017)

Elyassi, M., Rashidi, A., Hantehzadeh, M.Reza, Elahi, S.M.: Hydrogen storage behaviors by adsorption on multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 27, 285–295 (2017)

Jiang, M., Ou, G., Ma, R., Kao, K., Lin, W., Chen, J.: Deposition-float-assembly formation mechanism of continuous hollow cylindrical carbon nanotube sock via floating catalyst chemical vapor deposition. J. Mater. Sci. 54, 6961–6970 (2019)

Bhakta, A.K., Kumari, S., Hussain, S., Martis, P., Mascarenhas, R.J., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z.: Synthesis and characterization of maghemite nanocrystals decorated multi-wall carbon nanotubes for methylene blue dye removal. J. Mater. Sci. 54, 200–216 (2019)

Kilinç, E.: γ-Fe2O3 magnetic nanoparticle functionalized with carboxylated multi walled carbon nanotube: synthesis, characterization, analytical and biomedical application. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 401, 949–955 (2016)

Chungchamroenkit, P., Chavadej, S., Yanatatsaneejit, U., Kitiyanan, B.: Residue catalyst support removal and purification of carbon nanotubes by NaOH leaching and froth flotation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 60, 206–214 (2008)

Al-kahtani, A.A., Almuqati, T., Alhokbany, N., Ahamad, T., Naushad, M., Alshehri, S.M.: A clean approach for the reduction of hazardous 4-nitrophenol using gold nanoparticles decorated multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J. Clean. Prod. 191, 429–435 (2018)

Elbasuney, S., Zaky, M.G., Radwan, M., Sahu, R.P., Puri, I.K.: Synthesis of CuO nanocrystals supported on multiwall carbon nanotubes for nanothermite applications. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater. 29, 1407–1416 (2019)

Bhakta, A.K., Detriche, S., Kumari, S., Hussain, S., Martis, P., Mascarenhas, R.J., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z.: Multi-wall carbon nanotubes decorated with bismuth oxide nanocrystals using infrared irradiation and diazonium chemistry. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater. 28, 1402–1413 (2018)

Mccafferty, L., Stolojan, V., King, S.G., Zhang, W., Haq, S., Silva, S.R.P.: Decoration of multiwalled carbon nanotubes with protected iron nanoparticles. Carbon N. Y. 84, 47–55 (2015)

Scarselli, M., Camilli, L., Castrucci, P., Nanni, F., Gobbo, S.Del, Gautron, E., Lefrant, S., Crescenzi, M.De: In situ formation of noble metal nanoparticles on multiwalled carbon nanotubes and its implication in metal–nanotube interactions. Carbon N. Y. 50, 875–884 (2012)

Manasa, G., Bhakta, A.K., Mekhalif, Z., Mascarenhas, R.J.: Voltammetric study and rapid quantification of resorcinol in hair dye and biological samples using ultrasensitive maghemite/MWCNT modified carbon paste electrode. Electroanalysis 31, 1363–1372 (2019)

Bhakta, A.K., Detriche, S., Martis, P., Mascarenhas, R.J., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z.: Decoration of tricarboxylic and monocarboxylic aryl diazonium functionalized multi-wall carbon nanotubes with iron nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. 52, 9648–9660 (2017)

Khan, A.A., Kumari, S., Chowdhury, A., Hussain, S.: Phase tuned originated dual properties of cobalt sulfide nanostructures as photocatalyst and adsorbent for removal of dye pollutants. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 1, 3474–3485 (2018)

Eteya, M.M., Rounaghi, G.H., Deiminiat, B.: Fabrication of a new electrochemical sensor based on Au-Pt bimetallic nanoparticles decorated multi-walled carbon nanotubes for determination of diclofenac. Microchem. J. 144, 254–260 (2019)

Yang, Z., Li, L., Hsieh, C., Juang, R.: Co-precipitation of magnetic Fe3 O4 nanoparticles onto carbon nanotubes for removal of copper ions from aqueous solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 82, 56–63 (2018)

Chaudhary, D., Singh, S., Vankar, V.D., Khare, N.: ZnO nanoparticles decorated multi-walled carbon nanotubes for enhanced photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 351, 154–161 (2018)

Lee, S., Ham, J., Jeon, K., Noh, J., Lee, W.: Direct observation of the semimetal-to-semiconductor transition of individual single-crystal bismuth nanowires grown by on-film formation of nanowires. Nanotechnology. 21, 405701–405706 (2010)

Zhou, G., Li, L., Li, G.H.: Semimetal to semiconductor transition and thermoelectric properties of bismuth nanotubes. J. Appl. Phys. 109, 1143111–1143118 (2011)

Sharma, S., Mehta, S.K., Ibhadon, A.O., Kansal, S.K.: Fabrication of novel carbon quantum dots modified bismuth oxide (a-Bi2 O3/C-dots): material properties and catalytic applications. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 533, 227–237 (2019)

Ahamed, M., Akhtar, M.J., Khan, M.A.M., Alrokayan, S.A., Alhadlaq, H.A.: Oxidative stress mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis response of bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) nanoparticles in human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells. Chemosphere 216, 823–831 (2019)

Suib, N.R.M., Nur-Akasyah, J., Aizat, K.M., Abd-Shukor, R.: Electrical properties of nano Bi2O3 added (Bi, Pb) Sr-Ca-Cu-O superconductor. J. Phys: Conf. Ser. 1083, 1–6 (2018)

Malligavathy, M., Iyyapushpam, S., Nishanthi, S.T., Padiyan, D.P.: Remarkable catalytic activity of Bi2O3/TiO2 nanocomposites prepared by hydrothermal method for the degradation of methyl orange. J. Nanoparticle Res. 19, 144 (2017)

Lu, Y., Zhao, Y., Zhao, J., Song, Y., Huang, Z., Gao, F., Li, N., Li, Y.: Induced aqueous synthesis of metastable β-Bi2O3 microcrystals for visible-light photocatalyst study. Cryst. Growth Des. 15, 1031–1042 (2015)

Schlesinger, M., Schulze, S., Hietschold, M., Mehring, M.: Metastable β-Bi2O3 nanoparticles with high photocatalytic activity from polynuclear bismuth oxido clusters. Dalt. Trans. 42, 1047–1056 (2013)

Chowdhury, A., Khan, A.A., Kumari, S., Hussain, S.: Superadsorbent Ni–Co–S/SDS nanocomposites for ultrahigh removal of cationic, anionic organic dyes and toxic metal ions: kinetics, isotherm and adsorption mechanism. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 4165–4176 (2019)

Qiu, S., Zhou, Z., Dong, J., Chen, G.: Preparation of Ni nanoparticles and evaluation of their tribological performance as potential additives in oils. J. Tribol. 123, 441–443 (2001)

Tian, Y., Zhou, X., Huang, L., Liu, M.: A facile gas–liquid co-deposition method to prepare nanostructured nickel hydroxide for electrochemical capacitors. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 23, 1425–1430 (2013)

Gong, L., Liu, X., Su, L.: Facile solvothermal synthesis Ni(OH) 2 nanostructure for electrochemical capacitors. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 21, 866–870 (2011)

Patil, U.M., Gurav, K.V., Fulari, V.J., Lokhande, C.D., Joo, O.H.S.: Characterization of honeycomb-like “β -Ni(OH)2” thin films synthesized by chemical bath deposition method and their supercapacitor application. J. Power Sources. 188, 338–342 (2009)

Cerovac, S., Guzsvány, V., Kónya, Z., Ashrafi, A.M., Svancara, I., Roncevic, S., Kukovecz, Á., Dalmacija, B., Vytras, K.: Trace level voltammetric determination of lead and cadmium in sediment pore water by a bismuth-oxychloride particle-multiwalled carbon nanotube composite modified glassy carbon electrode. Talanta 134, 640–649 (2015)

Venugopal, B.R., Detriche, S., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z.: Effect of infrared irradiation on immobilization of ZnO nanocrystals on multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J. Nanopart. Res. 14, 1079 (2012)

Martis, P., Venugopal, B.R., Seffer, J.-F., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z.: Infrared irradiation controlled decoration of multiwalled carbon nanotubes with copper/copper oxide nanocrystals. Acta Mater. 59, 5040–5047 (2011)

Mahouche-Chergui, S., Gam-Derouich, S., Mangeney, C., Chehimi, M.M.: Aryl diazonium salts: a new class of coupling agents for bonding polymers, biomacromolecules and nanoparticles to surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 4143–4166 (2011)

Gonzalez-Gaitan, C., Ruiz-Rosas, R., Morallon, E., Cazorla-Amoros, D.: Functionalization of carbon nanotubes using aminobenzene acids and electrochemical methods. Electroactivity for the oxygen reduction reactions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 40, 11242–11253 (2015)

Mohamed, A.A., Salmi, Z., Dahoumane, S.A., Mekki, A., Carbonnier, B., Chehimi, M.M.: Functionalization of nanomaterials with aryldiazonium salts. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 225, 16–36 (2015)

Cao, A., Xu, C., Liang, J., Wu, D., Wei, B.: X-ray diffraction characterization on the alignment degree of carbon nanotubes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 344, 13–17 (2001)

Li, Y., He, C., Timofeeva, E.V., Ding, Y., Parrondo, J., Segre, C., Ramani, V.: β -Nickel hydroxide cathode material for nano-suspension redox flow batteries. Front. Energy. 11, 401–409 (2017)

Largani, S.H., Pasha, M.A.: The effect of concentration ratio and type of functional group on synthesis of CNT–ZnO hybrid nanomaterial by an in situ sol–gel process. Int. Nano Lett. 7, 25–33 (2017)

Xin, F., Li, L.: Decoration of carbon nanotubes with silver nanoparticles for advanced CNT/polymer nanocomposites. Compos. Part A 42, 961–967 (2011)

Dettlaff, A., Sawczak, M., Klugmann-Radziemska, E., Czylkowski, D., Miotkb, R., Wilamowska-Zawłocka, M.: High-performance method of carbon nanotubes modification by microwave plasma for thin composite films preparation. RSC Adv. 7, 31940–31949 (2017)

Sen, B., Kuzu, S., Demir, E., Akocak, S., Sen, F.: Highly monodisperse RuCo nanoparticles decorated on functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotube with the highest observed catalytic activity in the dehydrogenation of dimethylamine-borane. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42, 23292–23298 (2017)

Zhang, J., Zhang, X., Chen, S., Gong, T., Zhu, Y.: Surface-enhanced Raman scattering properties of multi-walled carbon nanotubes arrays-Ag nanoparticles. Carbon N. Y. 100, 395–407 (2016)

Maho, A., Detriche, S., Fonder, G., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z.: Electrochemical co-deposition of phosphonate-modified carbon nanotubes and tantalum on nitinol. ChemElectroChem. 1, 896–902 (2014)

Smith, M., Scudiero, L., Espinal, J., Mcewen, J., Garcia-perez, M.: Improving the deconvolution and interpretation of XPS spectra from chars by ab initio calculations. Carbon N. Y. 110, 155–171 (2016)

Datsyuk, V., Kalyva, M., Papagelis, K., Parthenios, J., Tasis, D., Siokou, A., Kallitsis, I., Galiotis, C.: Chemical oxidation of multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Carbon N. Y. 46, 833–840 (2008)

Yang, D., Sacher, E.: Carbon 1 s X-ray photoemission line shape analysis of highly oriented pyrolytic graphite: the influence of structural damage on peak asymmetry. Langmuir 22, 860–862 (2006)

Estrade-szwarckopf, H.: XPS photoemission in carbonaceous materials: a ‘“defect”’ peak beside the graphitic asymmetric peak. Carbon N. Y. 42, 1713–1721 (2004)

Puziy, A.M., Poddubnaya, O.I., Socha, R.P., Gurgul, J., Wisniewski, M.: XPS and NMR studies of phosphoric acid activated carbons. Carbon N. Y. 46, 2113–2123 (2008)

Liu, Z., Peng, F., Wang, H., Yu, H., Tan, J., Zhu, L.: Novel phosphorus-doped multiwalled nanotubes with high electrocatalytic activity for O2 reduction in alkaline medium. Catal. Commun. 16, 35–38 (2011)

Larrude, D.G., da Costa, M.M.E.H., Monteiro, F.H., Pinto, A.L., Freire Jr., F.L.: Characterization of phosphorus-doped multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 0643151–0643156 (2012)

Siow, K.S., Britcher, L., Kumar, S., Griesser, H.J.: XPS study of sulfur and phosphorus compounds with different oxidation states. Sains Malays. 47, 1913–1922 (2018)

Lee, K.Y., Hwang, H., Kim, T.H., Choi, W.: Enhanced photocatalytic activity of bismuth precursor by rapid phase and surface transformation using structure-guided combustion waves. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 8, 3366–3375 (2016)

Biesinger, M.C., Payne, B.P., Lau, L.W.M., Gerson, A., Smart, R.S.C.: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic chemical state quantification of mixed nickel metal, oxide and hydroxide systems. Surf. Interface Anal. 41, 324–332 (2009)

Bhakta, A.K., Mascarenhas, R.J., Martis, P., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z.: Multi-wall carbon nanotubes decorated with barium oxide nanoparticles. Synth. Catal. Open Access. 3, 1–4 (2018)

Blanch, A.J., Lenehan, C.E., Quinton, J.S.: Dispersant effects in the selective reaction of aryl diazonium salts with single-walled carbon nanotubes in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 1709–1723 (2012)

Doppelt, P., Hallais, G., Pinson, J., Podvorica, F., Verneyre, S.: Surface modification of conducting substrates. Existence of azo bonds in the structure of organic layers obtained from diazonium salts. Chem. Mater. 19, 4570–4575 (2007)

Jacques, A., Chehimi, M.M., Poleunis, C., Delcorte, A., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z.: Grafting of 4-pyrrolyphenyldiazonium in situ generated on NiTi, an adhesion promoter for pyrrole electropolymerisation? Electrochim. Acta 211, 879–890 (2016)

Jacques, A., Saad, A., Chehimi, M.M., Poleunis, C., Delcorte, A., Delhalle, J., Mekhalif, Z.: Nitinol modified by In situ generated diazonium salts as adhesion promoters for photopolymerized pyrrole. Chem. Sel. 3, 11800–11808 (2018)

Li, Q., Batchelor-McAuley, C., Lawrence, N.S., Hartshorne, R.S., Compton, R.G.: The synthesis and characterisation of controlled thin sub-monolayer films of 2-anthraquinonyl groups on graphite surfaces. New J Chem. 35, 2462–2470 (2011)

Acknowledgements

Arvind K. Bhakta thanks the University of Namur for a CERUNA doctoral fellowship. We also thank the PC2 platform UNamur for providing XRD facility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhakta, A.K., Kumari, S., Hussain, S. et al. Differently substituted aniline functionalized MWCNTs to anchor oxides of Bi and Ni nanoparticles. J Nanostruct Chem 9, 299–314 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40097-019-00319-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40097-019-00319-8