Abstract

Solar greenhouses can be considered as efficient places for biological CO2 capture and utilization if CO2 enrichment becomes a common practice there. As CO2 enrichment is applied only when greenhouses are closed, ventilated greenhouses––which represent a large percentage of greenhouses all over the world––cannot be considered for this practice. Consequently, ventilated greenhouses cannot be considered for CO2 capture and utilization. The aim of this paper is to show––through modeling and simulation––that these ventilated greenhouses can be activated for serving as efficient CO2 capture and utilization places if they are kept closed (to apply CO2 enrichment) and used microclimate control methods alternative to ventilation. The paper introduces a realistic mathematical model in which all the processes and phenomena associated with the biological CO2 capture and utilization by photosynthesis inside greenhouses are considered. The model validity and accuracy were ensured through the good agreement of its numerical predictions with the available experimental results in the literature. The effect of different environmental and planting conditions on the CO2 capturing process (the photosynthesis process) is investigated. A case study was chosen to investigate the effects of the cooling method, cooling temperature, planting conditions, and CO2 concentration level on the cumulative amount of captured CO2 which represents the greenhouse capturing performance. The results show that the capturing performance of greenhouse can be enhanced from value as low as 1.0 g CO2/m2 day for ventilated greenhouses with low planting density to a value as high as 140 g CO2/m2 day for high planting density when alternative microclimate control methods and CO2 enrichment are applied, considering the appropriate plant type. Additional benefits besides CO2 capture are also discussed for the possible increase of the plant productivity and possible lowering of water consumption by plants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Carbon dioxide is strongly blamed for being the major contributor to the global warming problem. The increase in burning fossil fuels increases CO2 concentration in the atmosphere and increases the effect of global warming. Therefore, solutions to reduce CO2 emissions to the atmosphere are necessary. In recent years, a new technology called carbon capture and storage (CCS) had been introduced to reduce CO2 emissions to the atmosphere [1]. In these technologies, CO2 is separated from the exhaust gas streams, compressed, and then treated for clean environment. This treatment can be either by permanently storing CO2 (e.g. geological reservoir) or by utilizing it in any beneficial application (food industry, water treatment, agriculture sector).

Biofixation is considered as one of the promising CO2 utilization applications in which terrestrial plants can capture and utilize considerable amounts of CO2 through the process of photosynthesis. The common application of biofixation is the increase of forestation to lower the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere [2–4]. Another possible application of biofixation, that is not receiving much attention, is the CO2 enrichment inside commercial greenhouses. Carbon dioxide enrichment is a process performed in some greenhouses in which pure CO2 is introduced to the vegetated crops at high concentration levels. This process leads to increasing the productivity of the crops inside the greenhouse as the photosynthesis rate of enriched plants is much higher than that of plants subjected to ambient CO2 concentration [5]. Considering this practice, if the pure CO2 supplied to plants inside the greenhouse is provided from the CO2 that was separated previously from a CO2 capturing process, this will allow the plants inside the greenhouse to utilize it at high rates instead of just burying it underground. Furthermore, greenhouses are currently occupying large areas all over the world and as these areas will continuously increase [6, 7], commercial greenhouses can be considered as promising places for efficient CO2 capturing and utilization if CO2 enrichment becomes a common practice there.

Unfortunately, CO2 enrichment is not commonly used in greenhouses. This is because applying CO2 enrichment requires greenhouses to be kept closed to preserve the supplied CO2 inside the greenhouse. Closing greenhouses requires the use of appropriate cooling and dehumidifying methods that can achieve favorable microclimate inside the greenhouse while it is closed, otherwise plants inside will be subjected to continuous and dangerous overheating from solar radiation. In fact, the default cooling and dehumidification method considered by a large percentage of greenhouses all over the world is ventilation, which contradicts with applying CO2 enrichment as CO2 can escape from the greenhouse through the ventilator openings. This means that these ventilated greenhouses cannot be considered for the CO2 capture and utilization purposes. Authors of the present work believe that ventilated greenhouse can be viewed as if they originally have high potential to capture and utilize CO2, but this potential is wasted due to the use of ventilation. Consequently, there should be a study that investigates whether using microclimate control methods alternative to ventilation can activate a significant environmental role of greenhouses by enabling them to effectively capture and utilize CO2 besides their major role of providing high quality crops. The present study aims to answer this question in which the aforementioned investigation is carried out theoretically through modeling.

Modeling of the biological CO2 capture and utilization in greenhouses is not a simple task due to the presence of many associated and interacting processes e.g., photosynthesis, microclimate control, CO2 enrichment, solar radiation processes, heat and mass transfer, etc. However, the literature is rich in modeling studies about greenhouses that includes some of these processes. These studies can be considered to be in two main areas: management of greenhouses microclimate, and CO2 enrichment practices.

Abdel-Ghany et al. [8] developed a dynamic heat and mass transfer model to investigate the effect of using fluid-roof system on the microclimate of a greenhouse. The model they developed neglected the CO2 mass balance and modeled the so-called stomatal conductance, the biological mass transfer conductance of plan leaves, using empirical relation that was limited to tomato crop only. Jain and Tiwari [9] developed a mathematical model to investigate the use of fan and pad cooling system on the greenhouses’ microclimate. Their model was based on energy balance equations for the different components of the greenhouse and neglected the water vapor and CO2 mass balance.

Chalabi et al. [10] developed a model that solves for the CO2 concentration that maximizes the margin between crop (tomato) value and CO2 cost under the prevailing weather conditions. Their model considered only the photosynthesis and the ventilation processes. They used empirical relations to express both the stomatal conductance and photosynthesis process in their model. Abdel-Ghany and Kozai [11] developed a dynamic mathematical model to investigate the use of natural ventilation together with intermittent fogging for cooling greenhouses under hot summer conditions. The model they developed was based on the energy balance equations of the greenhouse components and the mass balance equation of water vapor only.

Impron et al. [12] developed a greenhouse microclimate model to optimize cover properties and ventilation rates to reduce thermal load of greenhouses. Their model was restricted only to three state variables: average greenhouse air water vapor pressure, average greenhouse air temperature, and average canopy temperature. Kläring et al. [13] investigated the effect of maintaining CO2 concentration inside a closed greenhouse at the ambient level on the productivity of cucumber crop planted inside. They developed a CO2 enrichment strategy that was based on calculating the photosynthesis rate of cucumber through an empirical photosynthesis model and supplying the corresponding amount of CO2 to the greenhouse air. The photosynthesis model they used was originally developed for tomato crop but they used it to estimate photosynthesis rate of cucumber.

Vanthoor et al. [14] developed a greenhouse microclimate model with an aim of making this model generic to predict the microclimate of greenhouses for a broad range of environmental conditions all over the world. Their model was based on non-steady energy balance of the components of their greenhouse model (cover, inside air, canopy, and soil) besides mass balance of water vapor and CO2. Although their study is comprehensive, they modeled the photosynthesis process using an approximation of a mechanistic photosynthesis sub model, in which they considered only one potential of the three potentials decided by the photosynthesis model. The stomatal conductance model they used has a drawback that it does not consider the interaction between environmental conditions on stomata function. Mongkon et al. [15] developed a mathematical model to assess the cooling performance of a greenhouse cooled by horizontal earth tube system. Their model was based on energy balances of the greenhouse cover, inside air, plant canopy, and soil. It included water vapor mass balance but did not include CO2 mass balance.

From the previous short representative survey, the following points can be drawn. Most of the studies concerning greenhouses in the literature are directed towards its natural objective of improving the agricultural productivity of greenhouses (through either controlling the microclimate or applying CO2 enrichment), not with a main objective of using greenhouses for the environmental purpose of CO2 capture and utilization as in the present study. As a result, these studies may consider modeling of some of the processes associated with the biological CO2 capture and utilization, but not all of them. Most of the cooling methods of greenhouses microclimate are based on ventilation, thus high percentage of greenhouses are losing significant potential in capturing high amounts of CO2. Some research works investigated cooling methods that allow closing the greenhouse like liquid radiation filter. These works ensure the possibility of keeping the greenhouse closed to allow enriching the greenhouse to high levels of CO2 concentration. Most of the studies on managing the greenhouses microclimate simplified its analysis by considering the energy balance and water vapor mass balance only, and neglected the CO2 mass balance and the photosynthesis modeling in spite of their importance to the microclimate analysis.

Thus, the aim of the present work is to formulate, solve, and analyze the numerical predictions of a mathematical realistic model that includes all the complex and integrated events and processes associated with simulating the CO2 capturing performance of solar greenhouses, in both ventilated and closed conditions. These events and processes include solar radiation processes, heat and mass transfer, CO2 enrichment, photosynthesis, and microclimate control. The model accurately treats the solar radiation through the spectrum partitioning (visible and near infrared), attenuation of beam and diffuse components of solar radiation through the atmosphere, as well as absorption of solar radiation by the greenhouse cover, plant canopy, and the floor surface. In addition, it accounts for the estimation of radiative heat exchange between the various surfaces inside the greenhouse. The photosynthesis process is modeled using a precise mechanistic approach which is applicable to the commonly planted C3 species. This approach depends on plant biochemical kinetics in addition to plant canopy temperature and absorbed photosynthetic photon flux density. The present model provides a strategy for CO2 enrichment which keeps the CO2 concentration level inside the greenhouse at the required prescribed value within small-specified margin. In addition, it provides strategies for cooling and dehumidification that are based on estimating the required cooling and dehumidification specific rates that keep the microclimate temperature and relative humidity within the favorable limits. The present work uses total daily amount of captured CO2 as an indicator for describing the greenhouse capture and utilization performance. The model will be used to assess the capturing performance of greenhouses that use ventilation as microclimate control method and investigate the possible ways to improve this performance if alternative microclimate control methods are used.

Mathematical formulation

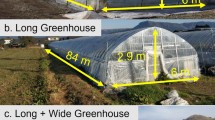

Figure 1 shows the important features of the greenhouse conceptual model. These features include dimensions of the greenhouse model, the main components of the model, the auxiliary systems of CO2 enrichment and ventilation, and the heat and mass transfer processes of the model. The greenhouse dimensions are height H, width W, and length L (perpendicular to the plane of the figure). The main components of the greenhouse related to the mathematical modeling are the plant canopy (leaves of plants as they are the active part of the plant which exchanges heat and mass fluxes with the environment), greenhouse inside air, greenhouse cover, and the greenhouse soil.

The CO2 capturing performance of the greenhouse is influenced by main events (CO2 enrichment and cooling of the greenhouse air) and heat and mass transfer processes. The CO2 enrichment is performed using pure CO2 that is obtained from a prior CO2 capture process and stored in storage tank. This CO2 is delivered to the plant canopy through a pipe system and injectors in such a manner that it gives a uniform CO2 concentration over the horizontal surface area of the canopy. Cooling and dehumidification of the greenhouse air can be performed either by the natural ventilation method or through an alternative cooling system. In the natural ventilation, ventilators (which are openings in the greenhouse cover) are opened to allow the exchange between the greenhouse air and the atmospheric air. In the alternative cooling method (represented by the cooling load arrow), the greenhouse air is brought to the required favorable air temperature value considering any appropriate system that can perform this task without opening the greenhouse ventilators (e.g., solar absorption cooling system).

Heat transfer processes occurs between the greenhouse components by the three modes of conduction, convection and radiation. Considering Fig. 1a, convective heat transfer occurs between the greenhouse inside air and the adjoining surfaces (canopy leaves, floor surface, and the inner side of the greenhouse cover) and between the outer surface of the cover with the ambient air. The conduction heat transfer occurs mainly into the greenhouse soil. Mass transfer processes occurs mainly between the plant canopy and the greenhouse air as the canopy exchanges CO2 and H2O through the photosynthesis and the transpiration processes, respectively. These two processes are affected by solar radiation, canopy’s temperature, and humidity of the greenhouse air. Also, there may be mass transfer between the water vapor of greenhouse inside air and the inner surface of the greenhouse cover in the form of condensation process. The shape of the cover roof allows the condensate to slips on the cover surface and to be collected away. This prevents the condensate from fallings on the plant canopy. Figure 1b shows both solar and thermal radiative exchanges processes. The cover is semi transparent in the wavelength of solar radiation and opaque in the wavelength of thermal radiation. The incident direct and diffuse solar fluxes of visible and near infrared spectrums suffer reflection, absorption, and transmission with the greenhouse components. Thermal radiation is exchanged between the surfaces of the greenhouse soil, canopy, and inner side of the cover. In addition, the outer surface of the cover exchanges thermal radiation with the sky.

The following assumptions are taken into consideration in the formulation of the basic equations of the mathematical model:

-

1.

Green leaves of the plant canopy are treated considering the big leaf approach. According to this approach, the overall plant canopy is assumed as a lumped system with uniform temperature, CO2 concentration, and humidity ratio represented by its Leaf Area Index (LAI). This index is used to express the total area of plant leaves that exchange heat and mass fluxes with the surroundings (m2 leaves “one side”/m2 ground).

-

2.

The greenhouse inside air is considered as well mixed with no spatial distribution of the corresponding microclimatic variables (temperature, CO2 concentration and humidity ratio).

-

3.

The greenhouse cover (side walls and roof) is thin enough to be considered as one lump in heat transfer analysis.

-

4.

The soil is a semi-infinite medium that extends in the direction of the Z-coordinate and is treated as a thick slab of thickness l in the numerical thermal analysis.

-

5.

The greenhouse soil is covered with thin plastic sheet to prevent any mass transfer of water that may evaporate from the soil to the greenhouse air.

-

6.

The greenhouse cover is considered to be blocking (reflecting) to the ultra violet (UV) spectrum of solar radiation.

-

7.

The greenhouse is oriented in the east–west direction.

-

8.

Greenhouse cover is tightly sealed against infiltration. The only exchange of the greenhouse air with the atmospheric air is through ventilation (if used).

-

9.

Any reflected solar radiation from the canopy will directly escape outside through the cover due to the high cover transmittance to solar radiation.

-

10.

The greenhouse inside air is not participating medium in radiation analysis due to the short optical depth of radiation.

-

11.

The surfaces of the greenhouse components involved in thermal radiation exchange are considered diffuse, gray, and opaque.

-

12.

The directional values of radiative properties for canopy, cover, and floor associated with solar radiation transport are assumed equal to the hemispherical values.

Basic balance equations of the model

The heat and mass transfer processes simulated by the model are governed by the following mass species and energy balance equations. The terms for the lumped systems of cover, inside air, and canopy represent specific rates (storage or source) defined as the rates per unit horizontal area of the greenhouse floor.

The mass species balance equation governing the CO2 concentration C(t) in the inside air is expresses as:

where \( \rho_{\text{air}} \) (kg/m3) and \( M_{\text{air}} \) (kg/mol) are the mass density and molecular weight of the dry air, respectively. The source term G (μmol/m2 s) accounts for the CO2 enrichment by injection. The source term −A n (μmol/m2 s) accounts for the net CO2 assimilation due to photosynthesis (CO2 uptake/capture) and respiration (CO2 release) by the plant canopy. The source term \( n_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} ,{\text{vent}}}}^{\prime \prime } \) (μmol/m2 s) accounts for the loss of CO2 by ventilation (if exists).

The mass species balance equation governing the humidity ratio \( \omega (t) \) in the inside air is expresses as:

The source term \( m_{\text{tran}}^{\prime \prime } \) (kg H2O/m2 s) accounts for transpiration from plant canopy. The source term \( - m_{\text{cond}}^{\prime \prime } \) (kg H2O/m2 s) accounts for the condensation of water vapor on the inner surface of the greenhouse cover. The source term \( - m^{\prime \prime }_{\text{dehumid}} \) (kg H2O/m2 s) accounts for of the removal of water vapor from the humid air to control the relative humidity of the inside air (if needed). The source term \( m_{{{\text{H}}_{2} {\text{O,vent}}}}^{\prime \prime } \) (kg H2O/m2 s) accounts for the exchange of water vapor due to ventilation (if exists).

The energy balance equation governing the inside air temperature T air(t) is expressed as:

The heat transfer terms \( q_{{\text{can}{\text{-}{\text air}}}}^{\prime \prime } \), \( q_{\text{floor-air}}^{\prime \prime } \), and \( q_{\text{cov-air}}^{\prime \prime } \) account, respectively, for the convection from canopy, floor, and to cover (W/m2). The terms \( h_{\text{g}} (T_{\text{can}} )m_{\text{tran}}^{\prime \prime } \) and \( h_{\text{g}} (T_{\text{cov}} )m_{\text{cond}}^{\prime \prime } \) account for the energy added from transpiration of the plant canopy and the energy removed due to condensation on the cover surface (W/m2), respectively. The term \( q_{\text{cool}}^{\prime \prime } \) accounts for the cooling load removed from the greenhouse air, when needed.

The energy balance equation governing the greenhouse cover temperature T cov(t) is expressed as:

where A floor = WL is the total floor area (m2), and \( \rho_{\text{cov}} \) (kg/m3), A cov (m2), \( \delta_{\text{cov}} \) (m), and C cov (J/kg K) are the density, the total surface area, the thickness and the specific heat of the greenhouse cover, respectively. The radiative heat transfer terms \( R_{{s\_{\text{cov}}}} \), R floor-cov, R can-cov, and R cov-sky accounts, respectively, for absorbed solar radiation, the net floor–cover and the net canopy–cover radiation exchanges, and cover radiation to sky (W/m2). The heat transfer terms \( q_{\text{cov-amb}}^{\prime \prime } \) and \( h_{\text{fg}} \left( {T_{\text{cov}} } \right)m_{\text{cond}}^{\prime \prime } \) account, respectively, for the convection to ambient and the energy into cover by condensation of water vapor (W/m2), respectively.

The energy balance equation governing the plant canopy temperature T can(t) is expressed as:

where \( \rho_{\text{leaf}} \) (kg/m3), \( \delta_{\text{leaf}} \) (m), and C leaf (J/kg K) are the density, thickness, and specific heat of the plant leaf, respectively. The radiative heat transfer terms R s_can and R floor-can accounts, respectively, for absorbed solar radiation and the net floor–canopy radiation exchange (W/m2). The term \( h_{\text{fg}} (T_{\text{can}} )m_{\text{tran}}^{\prime \prime } \) accounts for the energy out associated with transpiration (W/m2).

The energy balance equation for the non-steady one dimensional conduction governing the soil temperature T soil(z,t) is given by:

The associated boundary conditions are:

where \( \rho_{\text{soil}} \) (kg/m3), k soil (W/m K) and C soil (J/kg K) are the density, thermal conductivity, and specific heat of the soil, respectively. The base temperature is defined as the temperature at depth l at which the temperature is constant and is not affected by environmental conditions. In this study, T base is taken as 15 °C at l = 1.0 m [8].

Expressions of all terms in the model governing equations are provided in detail in the ESM appendix. However, it is important to describe here, in this main context, the role and/or functionality of the following terms: G, A n, \( m^{\prime \prime }_{\text{dehumid}} \), and \( q_{\text{cool}}^{\prime \prime } \).

The term G represents the specific rate of CO2 injected inside the greenhouse to keep the CO2 concentration inside the greenhouse C(t) nearly constant around the required high value within small-specified margins. It compensates for the reduction of C(t) value due to its consumption by the photosynthesis process and/or loss by ventilation (if exists). A CO2 enrichment strategy is developed in the present study to predict the accurate value of the specific rate G to achieve the aforementioned role. The term A n represents the specific rate of CO2 capture and utilization through the photosynthesis process. It is estimated through a mechanistic biochemical model that is applicable to all plant types of the C3 species (the commonly planted species on earth e.g. cucumber, tomato, pepper, etc.). This process is strongly affected by the environmental conditions of plant leaves temperature, absorbed visible radiation, and ambient CO2 concentration. It is also dependent on planting conditions that are the plant type represented by its biochemical capacity \( V_{{{\text{cmax}}0,{\text{leaf}}}} \) (μmol/m2 s) and the planting density represented by the plant LAI. The term \( m_{\text{dehumid}}^{\prime \prime } \) represents the specific rate of removing water vapor from the greenhouse inside air in a manner the keeps the relative humidity of the inside air practically constant around required favorable value within a small-specified margin. This dehumidification can be performed considering any available method that can keep the humidity of the greenhouse inside air at the favorable value while the greenhouse is closed (not ventilated). The term \( q_{\text{cool}}^{\prime \prime } \) represents the specific rate of cooling the greenhouse inside air in a manner that keeps the greenhouse inside air temperature practically constant around required favorable value within small-specified margin. This cooling can be performed considering any available method that can keep the temperature of the greenhouse inside air at the favorable value while the greenhouse is closed. Strategies for cooling and dehumidifying the greenhouse inside air are developed to predict the accurate value of the specific rates \( q_{\text{cool}}^{\prime \prime } \) and \( {\text{m}}_{\text{dehumid}}^{{^{\prime \prime } }} \) to achieve the aforementioned role.

Results and discussion

This section presents the numerical predictions of the proposed mathematical model (method of solution is provided in the ESM appendix). Results are divided into three sub sections. The first is about the model validation; the second is about studying the photosynthesis process characteristics, and the third is a case study which investigates the capturing performance of a representative commercial greenhouse.

Model validation

The validation of the present model is performed in two steps. The first is to validate the sub model used to simulate the photosynthesis processes to ensure its ability in simulating the CO2 capture and utilization process accurately. The second is to validate the whole model to check the model ability to simulate the real conditions of commercial greenhouses.

Concerning the photosynthesis process, the numerical predictions of the photosynthesis specific rate of cucumber crop under different environmental conditions of incident visible radiation, plant leaf temperature, and CO2 concentration were compared with corresponding experimental data [16, 17]. Figure 2a shows the good agreement between the sub model predictions and experimental data of the net assimilation specific rate.

To validate the whole model, experimental data of 720 m2 commercial greenhouse located in Almeria, Spain (36°30′N, 2°18′E) and planted by cucumber was considered [18]. The greenhouse was enriched to CO2 concentration of 700 ppm when it is closed and 350 ppm when it is ventilated. Ventilation set point of 25 °C was defined to start or stop ventilation. Required inputs for the model calculations were obtained from the data given in the experimental work. Both the diurnal variation of the incident visible radiation on the greenhouse and the CO2 concentration inside the greenhouse were given in the experimental study.

Figure 2b shows good agreement between the model predictions and the corresponding experimental data of the incident visible radiation on the greenhouse. In addition, it is noticeable from Fig. 2c that the model can accurately predict the greenhouse microclimate. It is clear that the model is able to predict the time of opening and closing of the greenhouse ventilators with sufficient accuracy. It is also remarkable that the CO2 enrichment strategy developed in the present study is able to keep the CO2 concentration at the required level when needed. Thus, it can be concluded that the model is valid for use and is able to represent the real conditions of greenhouses with reasonable accuracy.

Investigation of the photosynthesis process characteristics

As it is aimed to maximize the ability of commercial greenhouse in capturing the highest possible amount of injected CO2, it is important to study the characteristics of the photosynthesis process at first. This study can be performed by investigating the effect of the different environmental conditions and the planting conditions (LAI and plant type) on the photosynthesis process.

Figure 3a shows the effect of the plant canopy temperature on the net assimilation specific rate. It is obvious from the figure that the assimilation specific rate is sensitive to temperature. There is an optimum temperature at which the assimilation specific rate is at its maximum. If the plant canopy temperature is higher or lower than this value, the assimilation specific rate value drops. Moreover, it is noticeable that the increase of the plant canopy temperature beyond the optimal value has more adverse effect on the photosynthesis process than the decrease of the plant canopy temperature. This behavior should be considered in specifying the appropriate temperature of cooling the greenhouse air when cooling is required.

Effect of different conditions and parameters on the characteristics of the photosynthesis process. a Effect of canopy leaves temperature, b effect of CO2 concentration level, c effect of the value of the absorbed visible radiation, d effect of the biochemical capacity of the plant canopy. In generating any of the above results, the following values of parameters are used as long as they are not the variable parameter of the x-axis (canopy temperature = 25 °C, V cmax0,leaf = 50 μmol/m2 s, CO2 concentration = 350 ppm, absorbed visible radiation = 300 W/m2, LAI = 1)

Figure 3b shows the effect of CO2 concentration level the plant is subjected to on the assimilation specific rate. It is noticeable that increasing the CO2 concentration level increases the photosynthesis specific rate. However, after a CO2 concentration of about 600 ppm, the increase of CO2 concentration does not have significant effect on the photosynthesis specific rate value. Considering this behavior, a CO2 concentration value of 950 ppm can be used to represent the CO2 concentration at which maximum assimilation specific rate from a plant type can be obtained. This concentration is also the safe concentration value for the most plant types [5] and is the one considered in the case study in “Case study of the CO2 capturing performance of a commercial greenhouse”.

Figure 3c shows the effect of absorbed visible radiation by the plant on its assimilation specific rate. It is clear from the figure that the assimilation specific rate increases with the increase of the irradiance level until a value after which the assimilation specific rate exhibits saturation behavior. Thus, if it is required to maximize the assimilation specific rate for any plant type, the plant must be subjected to an irradiance level that makes the assimilation specific rate in the saturation zone. This can be achieved naturally if there is sufficient lighting from the sun (e.g. summer conditions) or artificially using artificial lighting.

Planting conditions (plant type and LAI) can dramatically influence the capturing performance of commercial greenhouses. This planting conditions are numerically represented by the biochemical capacity of plant canopy V cmax0,can as V cmax0,can = V cmax0,leaf LAI where V cmax0,leaf is a plant type dependent. Figure 3d shows that assimilation specific rate increases with the increases of the biochemical capacity of the plant canopy until it reaches saturation. However, the assimilation specific rate reaches to enormous values with the increase of the biochemical capacity of the plant canopy compared to the increase with irradiance or CO2 concentration. As the plant LAI is strongly coupled with the age of the plant, the CO2 captured amount will continuously increase with the increase of the plant age (LAI) till it reaches a maximum value before harvesting. Also, selection of a plant type that has basically a high biochemical capacity, V cmax,leaf will further maximize the amount of CO2 captured by the plant besides the increase of that capacity with the increase of the plant LAI.

Case study of the CO2 capturing performance of a commercial greenhouse

The aim of this case study is to prove that commercial greenhouses can play significant environmental role in capturing large amounts of CO2 if there are adequately operated to perform this task. Thus, this section considers the results of “Investigation of the photosynthesis process characteristics” to enable the greenhouse to do its capturing role efficiently. The study investigates the effect of cooling method, cooling temperature, biochemical capacity of plant canopy, and the CO2 enrichment on the capturing performance of a representative greenhouse. The study considers that the CO2 capturing performance of greenhouses can be represented by total amount of CO2 (that is externally injected to it, not coming from ambient through ventilation if used) captured by the plant inside the greenhouse. In the following investigations, simulations begin from the sunrise time until the sunset time. For each simulation, CO2 is injected to the greenhouse air to keep the CO2 concentration at the required high level whenever the greenhouse is closed. Cooling and dehumidification of the greenhouse air when the greenhouse is closed is performed considering the presence of an alternative cooling method and dehumidification methods to control the air temperature and relative humidity, respectively, to the favorable level. The total captured amount of CO2 \( {\text{Sum}}\_A_{\text{net}} \) is estimated by the following equation:

Effect of cooling method on the CO2 capturing performance

This section compares the capturing performance of the greenhouse when it is cooled by ventilation and using alternative method that allows cooling the greenhouse when it is closed. The greenhouse is intended to be in hot summer weather conditions so that the need for a cooling process to the greenhouse air is essential. The place of greenhouse is considered to be Cairo, Egypt with latitude of 30° and the day of year is 200 (19th of July). Figure 4 shows the corresponding predicted environmental conditions of the diurnal solar radiation flux and ambient temperature associated with the considered place and time of the simulation.

When the greenhouse is cooled by ventilation, ventilation set point T vent = 25 °C is considered to be the temperature at which ventilators should open and close if the greenhouse air temperature reaches to it. Also, if the greenhouse is cooled by the alternative cooling method, the set point for the greenhouse air temperature to start cooling is also T air = 25 °C. The alternative cooling should keep the inside air temperature at T air = 25 ± 2 °C margin. If dehumidification is needed, a relative humidity value of 75 ± 5 % is considered. The plant type considered in this simulation is cucumber. It has a biochemical capacity V cmax0,leaf = 50 μmol m−2 s−1 [19] and the LAI considered is 1.0.

Figure 5a shows the diurnal variation of the greenhouse air temperature when it is cooled by ventilation. The greenhouse air temperature reaches the ventilation set point after about 1 h from the sunrise time. During the day, the greenhouse air temperature is continuously increasing preventing closing of the greenhouse again before the sunset time. On the contrary, when the greenhouse is cooled and dehumidified by alternative methods, the greenhouse is kept closed throughout the daylight period at the favorable required conditions of air temperature and relative humidity. Figure 5b, c shows that the temperature and the relative of air inside the greenhouse are nearly constant around the required value for the daylight period.

Microclimate conditions of the greenhouse inside considering two different cooling methods. a Greenhouse inside air temperature when ventilation is used, b greenhouse inside air temperature when alternative cooling method is used, c greenhouse inside air relative humidity when alternative dehumidifying method is used

Because CO2 enrichment is applied when the greenhouse is closed only, it will be applied for a very short time when the greenhouse is cooled by ventilation compared to when it is cooled alternatively. This is clear in Fig. 6a as CO2 concentration is nearly constant throughout the daylight period at 950 ± 10 ppm when the greenhouse is alternatively cooled, whereas its value was preserved at 950 ppm for only 1 h when ventilation is used. A direct consequence of this is the large difference of the total captured amount of CO2 between the two cases of cooling as shown in Fig. 6b. The plant inside the greenhouse captured less than 1.0 g/m2 day of CO2 when ventilation is used, whereas it captured nearly 52 g/m2 day of CO2 when alternative cooling is used. This large difference emphasizes the strong inherent potential of commercial greenhouses to capture high amounts of CO2.

The result of Fig. 6b is obtained by keeping the greenhouse air temperature at 25 °C as the same temperature specified for the ventilation process. As the photosynthesis process is temperature sensitive, the effect of different temperatures of the greenhouse on the assimilation specific rate must be investigated, as cooling the greenhouse air to 25 °C may not be the best choice from the CO2 capturing point of view.

Effect of the cooling temperature

Figure 7a shows the effect of three different temperatures, the greenhouse air is cooled to, on the assimilation specific rate values. It is clear from the figure that cooling the greenhouse air to 21 °C has better effect on the photosynthesis process than the previously used 25 °C. It also shows that increasing the greenhouse air temperature has a negative effect on the photosynthesis process, a result that was previously introduced in “Investigation of the Photosynthesis Process Characteristics”. Figure 7b shows the associated captured amount of CO2 at the three different greenhouse temperatures. It is clear that the higher the greenhouse air temperature, the lower the captured amount of CO2.

Effect of the biochemical capacity of the plant canopy

In this section, the effect of the plant LAI and the plant type on the CO2 capturing performance of the greenhouse is investigated. The same greenhouse conditions of the previous simulation is considered but with LAI = 3 instead of LAI = 1. Figure 8a shows the continuing ability of the greenhouse to capture higher amounts of CO2 during its growing period provided that CO2 enrichment and alternative cooling are applied. Figure 8b shows the effect of changing the plant biochemical capacity by changing the plant type on the CO2 captured amount. The tomato crop which has the biochemical capacity V cmax0,leaf = 90 μmol/m2 s is considered in place of cucumber which has V cmax0,leaf = 50 μmol/m2 s used in the previous simulation. The figure shows that, for the same LAI, a greenhouse planted by tomato has more potential to capture higher amounts of CO2 than cucumber (140 g/m2 day instead of 120 g/m2 day). This demonstrates that, if the vision of using greenhouses for capturing CO2 is kept in mind, even the plant type selected for planting inside the greenhouse can play a significant role in enhancing the capturing performance of greenhouses.

Effect of CO2 enrichment level

In this section, the effect of CO2 enrichment level on the CO2 capturing performance of closed greenhouses is investigated. The greenhouse is already closed and CO2 enrichment is applied; however, the enrichment level may not be the highest possible level allowable to the plant as in some greenhouses, the CO2 enrichment level is limited to the ambient CO2 concentration only [13]. Thus, it is important to investigate to what extent CO2 enrichment level can affect the capturing performance of greenhouses. Additional benefits (besides CO2 capture) associated with the CO2 enrichment process is also introduced.

Figure 9a shows the difference between the CO2 captured amount in a closed greenhouse planted by tomato with LAI = 3 when it is subjected to the ambient CO2 concentration level (360 ppm) and a high level (950 ppm). It is noticeable that increasing the CO2 concentration increases the assimilation specific rate and in turn, the CO2 captured amount. This means that greenhouses which apply CO2 enrichment but to ambient level only should increase the concentration level there as this will effectively improve the capturing performance of the greenhouse.

A valuable advantage besides CO2 capture can be concluded from Fig. 9b. When the photosynthesis specific rate increases for a crop, the time required for its growing decreases. This can lead to the utilization of the same planted area to be cultivated more than the usual times when CO2 enrichment is not applied or applied but limited to ambient level. As it is highly aimed in many places in the world to increase the productivity of the same planted area, CO2 enrichment in commercial greenhouses can be the proper practice to achieve this task.

Another benefit from CO2 enrichment is that when stomata has sufficient supply of CO2, it does not need to be fully open to get high amount of CO2 as CO2 is already supplied to it in high rates. Thus, the stomata opening decreases. As the loss of water vapor through transpiration happens through stomata, less stomata opening means less water loss. Figure 10 shows the difference between the transpiration specific rate of tomato at the two different CO2 concentrations. It is obvious that considerable saving of water can be performed through this practice. This saving is so valuable to the whole world which is concerned from suffering from water poverty problems.

Conclusion

The present study has proposed, formulated and solved a non-steady mathematical model that investigated the CO2 capturing performance of commercial greenhouses. The model accuracy was verified through the well agreement between the model numerical predictions and the experimental work available in the literature. The model is used to investigate the conditions that affect the photosynthesis process to benefit from greenhouses in capturing high amounts of CO2. Numerical predictions of the model for a representative case study were presented and discussed to investigate the effect of different conditions of cooling method, cooling temperature, planting conditions, and CO2 enrichment level on the capturing performance of the commercial greenhouses. The main conclusions of the present study can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

The CO2 capturing performance of a greenhouse was improved in terms of increasing the total CO2 captured amount from a value as low as 1.0 to a value as high as 52 g CO2/m2 day when shifting from ventilation to an appropriate cooling and dehumidifying method.

-

2.

Keeping alternative microclimate control methods, the greenhouse performance is increased nearly twice with increasing the value of LAI from 1.0 to 3.0 for the same plant type.

-

3.

For conditions of alternative cooling with LAI value of 3.0, a CO2 capture performance as much as 120 g/m2 day was reached for the cucumber crop while a corresponding value of 140 g CO2/m2 day was reached for the tomato crop.

-

4.

CO2 enrichment in closed commercial greenhouses, in addition to getting rid of large quantities of CO2, helps in reducing water consumption and in the increase of productivity of plants from the same planted area.

-

5.

The present model can be considered as a valuable tool to predict the CO2 captured amount from any plant type in a certain area and period, or to select the appropriate plant type to capture a specified target of CO2 injection during the growing period of the plant. This is due to the power of the generic and mechanistic photosynthesis model used in the present study.

Abbreviations

- A n :

-

Net assimilation specific rate, μmol CO2/m2/s1

- A x :

-

Surface area of greenhouse component x, m2

- C :

-

CO2 concentration inside the greenhouse air, μmol/mol air

- C d, C w :

-

Drag coefficient and wind coefficient, respectively

- C x :

-

Specific heat of greenhouse component x other than air, J/kg K

- G :

-

CO2 injection specific rate for enrichment, μmol CO2/m2/s1

- H :

-

Greenhouse height, m

- h fg :

-

Latent heat of vaporization, J/kg

- h g :

-

Enthalpy of saturated water vapor, J/kg

- k :

-

Thermal conductivity, W/m K

- L :

-

Greenhouse length, m

- LAI:

-

Leaf Area Index

- l :

-

Depth of the greenhouse soil, m

- M air :

-

Molecular weight of the greenhouse air, kg/mole

- m″:

-

Mass transfer specific rate, kg/m2 s

- \( n_{{{\text{CO}}_{2} ,{\text{vent}}}}^{\prime \prime } \) :

-

Molar specific rate accounting for the loss of CO2 by ventilation, μmol/m2/s1

- P air-dry :

-

Dry air pressure, kPa

- P 0 :

-

Atmospheric air pressure at sea level, kPa

- \( q_{{{\text{solid}} - {\text{fluid}}}}^{\prime \prime } \) :

-

Convective heat specific rate between the humid air and the cover inner surface, W/m2

- \( q_{\text{cool}}^{\prime \prime } \) :

-

Energy specific rate accounting for cooling of the greenhouse by ventilation or other alternative cooling method, W/m2

- \( R_{{{\text{d}},{\text{vis}}/{\text{NIR}}}} \) :

-

Direct visible and near infrared solar radiation fluxes, respectively, W/m2

- \( R_{{{\text{df}},{\text{vis}}/{\text{NIR}}}} \) :

-

Diffuse visible and near infrared solar radiation fluxes, respectively, W/m2

- \( R_{s - x} \) :

-

Solar radiation specific rate absorbed by the greenhouse component x, W/m2

- \( R_{x - y} \) :

-

Net thermal radiation energy specific rate exchanged between surface x and surface y of the greenhouse, W/m2

- \( R_{{0,{\text{vis}}/{\text{NIR}}}} \) :

-

Extraterrestrial visible and near infrared solar radiation fluxes, respectively, W/m2

- T x :

-

Temperature of the greenhouse x component, K

- t :

-

Time, s

- u, u g :

-

Specific internal energy of the greenhouse air and dry saturated water vapor J/kg, respectively

- \( V_{{{\text{cmax}}0}} \) :

-

Biochemical capacity of the plant (carboxylation specific rate), μmol/m2 s

- W :

-

Greenhouse width, m

- \( \rho \) :

-

Material density, kg/m3

- \( \omega \) :

-

Humidity ratio of the greenhouse air, kg H2O/kg air

- air:

-

Greenhouse air

- atm:

-

Atmosphere

- base:

-

Base of the greenhouse soil

- cov:

-

Greenhouse cover

- can:

-

Canopy

- cond:

-

Condensation

- cool:

-

Cooling

- dehumid:

-

Dehumidification

- floor:

-

Greenhouse floor

- leaf:

-

Leaf

- sky:

-

Sky

- soil:

-

Soil

- tran:

-

Transpiration

References

Metz, B., Davidson, O., Coninck, H.D., Loos, M., Meyer, L.: IPCC Special Report on Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage. Geneva (Switzerland) (2005)

Protocol, K.: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Kyoto Protocol, Kyoto (1997)

Huang, L., Liu, J., Shao, Q., Xu, X.: Carbon sequestration by forestation across China: past, present, and future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16(2), 1291–1299 (2012)

Escobedo, F.J., Seitz, A., Zipperer, W.C.: Carbon sequestration and storage by Gainesville’s urban forest. Florida Cooperative Extension Services (2009)

Mortensen, L.: Review: CO2 enrichment in greenhouses. Crop responses. Sci. Hortic. 33, 1–25 (1987)

http://www.st-benedict-biscop.com/printpages/GreenhouseTechGlobally.pdf. Accessed 01 May 2014

von Zabeltitz, C.: Integrated Greenhouse Systems for Mild Climates. Springer, New York (2011)

Abdel-Ghany, A.M., Kozai, T., Taha, I.S., Abdel-Shafi, N.Y., Huzayyin, A.S.: Dynamic simulation modeling of heat and water vapor transfer in a fluid-roof greenhouse. J. Agric. For. Meteorol. 54(2), 169–182 (2001)

Jain, D., Tiwari, G.N.: Modeling and optimal design of evaporative cooling system in controlled environment greenhouse. Energy Convers. Manag. 43, 2235–2250 (2002)

Chalabi, Z.S., Biro, A., Baileys, B.J., Aikman, D.P., Cockshull, K.E.: Optimal control strategies for carbon dioxide enrichment in greenhouse tomato crops-part 1: using pure carbon dioxide. Biosyst. Eng. 81(4), 421–431 (2002)

Abdel-Ghany, A., Kozai, T.: Dynamic modeling of the environment in a naturally ventilated, fog-cooled greenhouse. Renew. Energy 31, 1521–1539 (2006)

Impron, I., Hemming, S., Bot, G.P.A.: Simple greenhouse climate model as a design tool for greenhouses in tropical lowland. Biosyst. Eng. 98, 79–89 (2007)

Kläring, H.-P., Hauschild, C., Heißner, A., Bar-Yosef, B.: Model-based control of CO2 concentration in greenhouses at ambient levels increases cucumber yield. Agric. For. Meteorol. 143(3–4), 208–216 (2007)

Vanthoor, B.H.E., Stanghellini, C., van Henten, E.J., de Visser, P.H.B.: A methodology for model-based greenhouse design: part 1, a greenhouse climate model for a broad range of designs and climates. Biosyst. Eng. 110(4), 363–377 (2011)

Mongkon, S., Thepa, S., Namprakai, P., Pratinthong, N.: Cooling performance assessment of horizontal earth tube system and effect on planting in tropical greenhouse. Energy Convers. Manag. 78, 225–236 (2014)

Goudriaan, J.: Crop Micrometeorology: A Simulation Study. Center for Agricultural Publishing and Documentation, Pudoc (1977)

Shibuya, T., Endo, R., Kitamura, Y.: Potential photosynthetic advantages of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seedlings grown under fluorescent lamps with high red: far-red light. HortScience 45(4), 553–558 (2010)

Sánchez-Guerrero, M., Lorenzo, P., Medrano, E., Castilla, N., Soriano, T., Baille, A.: Effect of variable CO2 enrichment on greenhouse production in mild winter climates. Agric. For. Meteorol. 132(3), 244–252 (2005)

Wullschleger, S.: Biochemical limitations to carbon assimilation in C3 plants—a retrospective analysis of the A/Ci curves from 109 species. J. Exp. Bot. 44(262), 907–920 (1993)

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest related to this manuscript. The manuscript has not been submitted or published elsewhere.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Effat, M.B., Shafey, H.M. & Nassib, A.M. Solar greenhouses can be promising candidate for CO2 capture and utilization: mathematical modeling. Int J Energy Environ Eng 6, 295–308 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40095-015-0175-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40095-015-0175-z