Abstract

Resonant third harmonic generation of super-Gaussian laser beam in rippled density plasma is studied. Both the relativistic and ponderomotive nonlinearities are included in the analysis, and the study is done for self-guided laser beam. The quasi-static component of ponderomotive force creates electron density depression in the beam region while the second harmonic component leads to second harmonic density oscillations, leading to third harmonic generation. The relativistic mass variation supplements these processes with same order of contributions. The ripple provides the phase matching and requisite ripple wave number decreases with the frequency of the laser.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and motivation

The generation of harmonics by the interaction of intense short pulse laser with plasma is a topic of continued interest because of its potential for producing coherent ultraviolet radiation to X-ray pulses [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Since plasma is a dispersive medium, the wave number of the nth harmonic does not match with n times the wave number of the fundamental laser beam and so, the harmonic generation is a non-resonant process. However, one may turn it into a resonant process by introducing a density ripple of wave number q equal to the wave number mismatch [7,8,9]. The ripple acts as virtual photons of zero energy and finite momentum and compensates for the momentum mismatch in the harmonic emission process.

Lin et al. [10] successfully fabricated the spatial structures with the help of laser machining beam in a hydrogen jet using spatial light modulator. Third harmonic generation employing such a density ripple was observed experimentally by Kuo et al. [11]. They found an order of magnitude enhancement in third harmonic efficiency. The formation of density bunches by the interaction of microwave in a plasma-filled waveguide has been analytically analyzed by Malik [12]. Liu and Tripathi [13] developed an analytical theory for third harmonic generation of a plane uniform laser beam in a plasma density ripple. Dahiya et al. [14] carried out particle-in-cell (PIC) simulation of harmonic generation in ripple density plasma and observed similar results. Kaur and Sharma [15] studied third harmonic generation (THG) from a high-density inhomogeneous plasma produced by laser irradiation of a thin metallic film and observed enhancement in the efficiency of THG with the increase in the density scale length of the plasma. The self-focusing of Gaussian laser beam has also been found to enhance the efficiency in third harmonic generation [16]. Singh and Walia [17] carried similar studies on second harmonic generation.

This is evident that most of the studies have been carried out for Gaussian laser beam, cosh-Gaussian (ChG) laser beam, and hollow Gaussian laser beam (HGB) [18,19,20,21,22]. Currently, there is significant interest in super-Gaussian laser beams [23,24,25], as these have fairly uniform intensity in the central spot and a sharp fall at the margins. In laser-driven ion acceleration, a super-Gaussian laser beam would cause much less divergence of the ion beam than that due to a Gaussian beam. In harmonic generation too, super-Gaussian beam should produce much wider radial intensity profile of the harmonic, leading to suppression of diffraction divergence. Keeping in mind all these points, we study in the present work a resonant third harmonic generation of super-Gaussian (sG) laser beam in a rippled density plasma on the time scale where ions are treated immobile. The laser is assumed to be plane polarized and to propagate along the periodicity of the ripples. It modifies the electron mass due to the relativistic effect and exerts quasi-static and second harmonic ponderomotive forces on the electrons. The quasi-static ponderomotive force pushes the electrons radially out, leaving behind an ion space charge. A steady state is realized when the ponderomotive force is balanced by the space charge force and a depressed electron density channel is created. The second harmonic ponderomotive force induces electron density oscillations, which in conjunction with relativistic mass oscillations beat with the electron velocity due to the pump to produce third harmonic current and hence, the third harmonic radiation. The process becomes resonant when the wave number of the density ripple matches the difference between the third harmonic wave number and 3 times the wave number of the laser pump.

Plasma channel equilibrium

Consider a collisionless plasma channel of electron density \( n = n_{0} + n_{q} \) together with density ripple \( n_{q} = n_{q0} e^{iqz} \). A linearly polarized laser beam propagates through it with the electric and magnetic fields as

where \( E_{0} = E_{00} { \exp }\left( { - r^{4} /2r_{0}^{4} } \right) \) and \( r_{0} \) represents the width of the laser beam, \( \eta \) is the refractive index. The density ripples can be created by laser machining beam in gas jet experiments. The machining laser pulse propagating in y-direction can be used to create density ripples, where the laser pulse propagating after a delay of the order of ns in the z-direction is taken to be the main pulse. The machining laser pulse has periodic intensity variation in z-direction and the maximum intensity that is greater than the threshold for optical field ionization of the neutral gas jet target is projected transversely on the neutral gas target. The plasma is formed on the positions of intensity maxima. After the machining laser pulse is gone, we achieve interlacing layers of high-density neutral gas and low-density plasma. Lin et al. [10] have successfully fabricated these types of density ripples by laser machining beam in a hydrogen jet using spatial light modulator. The ripples in density may also be produced using techniques, which involve transmissive ring grating and a patterned mask where the control of ripple parameters might be possible by changing the groove structure, groove period, and duty cycle in such a grating and by adjusting the period and size of the mask [12, 21].

The pulse duration of the laser is considered to be larger than the inverse electron plasma frequency but much shorter than the inverse ion plasma frequency. The ions move under the influence of electromagnetic field of the laser on the time scale greater than inverse ion plasma frequency. Hence, their response (density oscillation, velocity perturbation) is much smaller than the electron perturbation due to their heavy mass. It means the ion motion can be ignored. The electrons acquire an oscillatory velocity due to the laser’s field given by

and experience a quasi-static ponderomotive force given by

This is obtained from the relation \( \vec{F}_{\text{P}} = - \frac{m}{2}Re\left( {\vec{v}^{*} \cdot \nabla \left( {\gamma \vec{v}} \right)} \right) - \frac{e}{2}Re\left( {\vec{v}^{*} \times \vec{B}} \right) \) along with the use of the velocity \( \vec{v} \). The ponderomotive force pushes the electrons radially outward, creating a space charge field but ion motion is unimportant due to long pulses. Due to this space charge imbalance, an electrostatic field \( E_{\text{s}} \) is created given by \( E_{\text{s}} = - \nabla \varPhi_{\text{s}} \). In the quasi-static state \( \varPhi_{\text{s}} = - \varPhi_{\text{P}} \). From Poisson’s equation, the modified electron density is given by

Using Eq. (3), we can rewrite above expression in terms of normalized laser field amplitude \( a = \frac{e\left| E \right|}{m\omega c} \) as

Solving the above expression, we can write

\( a^{2} = a_{0}^{2} e^{ - x} \) and \( x = \frac{{r^{4} }}{{r_{0}^{4} }},\,a_{0} = \frac{{eE_{00} }}{{m\omega_{0} c}} \) is the normalized field amplitude of laser at \( r = 0 \).

Since super-Gaussian beams have less intensity variation from 0 to \( r_{0} \), when it travels in a nonlinear medium, we can define the permittivity to average permittivity as

where

Using Eqs. (6) and (7), the average permittivity can be written as

where

The wave number is written as

Self-guided beams are the parallel beams which propagate in the medium as a balance between diffraction divergence and nonlinear refraction. The beam making an angle \( \theta_{\text{D}} \) with the axis will suffer total internal reflection when this angle of diffraction \( \theta_{\text{D}} \) is less than the critical angle \( \theta_{\text{c}} \). At an angle \( \theta_{\text{D}} = \theta_{\text{c}} \), the nonlinear refraction just balances the diffraction effects and beam propagates as a self-guided beam. Since here we are considering the beam to be self-guided, angle of diffraction \( \theta_{\text{D}} \) should be equal to critical angle \( \theta_{\text{c}} \) (Fig. 1).

The angle of diffraction is given by

From Fig. 1, the angle of diffraction in terms of critical angle can be written as

The critical angle is given by

Using Eq. (13), considering small angle of diffraction Eq. (14) can be written as

Substituting the value of \( \bar{\varepsilon } \) and \( \varepsilon_{0} \), we can write

\( \alpha \) is a function of \( \frac{{\omega_{P0}^{2} r_{0}^{2} }}{{c^{2} }} \) and \( a_{0} \). The points where L.H.S and R.H.S. of Eq. (16) are equal corresponding to the values of \( \frac{{\omega_{P0} r_{0} }}{c} \) and \( a_{0} \) gives the permissible values of \( a_{0} \) for which the self-guiding takes place.

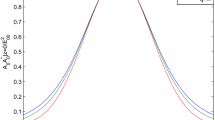

Figure 2 essentially depicts a technique to solve graphically algebraic Eq. (16). It shows the plot of L.H.S and R.H.S of Eq. (16) versus \( \frac{{\omega_{P0} r_{0} }}{c} \) for different \( a_{0} \). The points of intersection of L.H.S. of Eq. (16) for different \( a_{0} \) and R.H.S give the particular values of \( \frac{{\omega_{P0} r_{0} }}{c} \) and \( a_{0} \) for which the self-guiding of the laser beam takes place.

Plot of L.H.S and R.H.S. of Eq. (16) versus \( \frac{{\omega_{P0} r_{0} }}{c} \) for different \( a_{0} \)

The values of \( \frac{{\omega_{P0} r_{0} }}{c} \) and \( a_{0} \) for which L.H.S and R.H.S. of Eq. (16) are equal are tabulated in Table 1.

Figure 3 shows the variation of normalized laser field amplitude \( a_{0} \) versus normalized spot size \( \frac{{\omega_{P0} r_{0} }}{c} \) for which self-guiding of the laser beam takes place. As we increase the spot size, the requisite amplitude (hence, the intensity) of the laser beam for self-guiding decreases. This is due to the fact that diffraction divergence decreases with the spot size and hence weaker nonlinear refraction or self-convergence is required to compensate for it. At lower spot size saturating nature of relativistic nonlinearity becomes significant.

Third harmonic generation

The laser also exerts second harmonic ponderomotive force on the electrons at 2ω, 2k, given by

The force gives rise to \( \vec{v}_{2\omega , 2k} \) through the following equation of motion

Here \( \vec{E}_{2\omega } \) is the self-consistent field at \( 2\omega \) frequency. Using Poisson’s equation and equation of continuity, we can write

where \( \varepsilon_{2\omega } = 1 - \frac{{\omega_{P0}^{2} }}{{4\omega^{2} }}\frac{{n_{e} }}{{n_{0} \gamma }} \)

Oscillatory velocity \( \vec{v}_{2\omega , 2k} \) couples with \( n_{q} \) through the equation of continuity to produce density perturbation at \( 2\omega , \;2k + q \),

This perturbation beats with \( \vec{v}_{\omega , k} \) to give rise to third harmonic nonlinear current density,

The linear current density can be written as

The wave equation for the third harmonic field is

Taking \( \vec{E}_{3\omega } = \widehat{x}A_{3\omega } \left( {z,r} \right)e^{{ - i\left( {3\omega t - k_{3} z} \right)}} \) where \( k_{3} = \frac{3\omega }{c}\left( {1 - \frac{{\omega_{P0}^{2} }}{{9\omega^{2} }}\alpha } \right)^{1/2} \) in Eq. (23), it can be written as

Here this can be noticed that the source term on the right-hand side contains exponential factor which is a function of \( \left( {k_{3} - \left( {3k + q} \right)} \right)z \). The response of third harmonic field \( E_{3\omega } \) is maximum only when \( k_{3} = \left( {3k + q} \right) \) which is phase matching condition. For phase matching \( k_{3} = \left( {3k + q} \right) \) which gives \( q = \frac{4\omega }{3c}\frac{{\omega_{P0}^{2} }}{{\omega^{2} }}\alpha \). Taking \( A_{3\omega } = e^{{ - \frac{{3r^{4} }}{{2r_{0}^{4} }}}} F_{3} \left( z \right) \) and multiplying the resulting equation by \( e^{{ - \frac{{3r^{4} }}{{2r_{0}^{4} }}}} r{\text{d}}r \) and integrating from 0 to \( \infty \), we get the following equation

where \( \beta_{3} = \mathop \int \limits_{0}^{\infty } r{\text{d}}r\left[ {\alpha - \left( {1 + \frac{{a_{0}^{2} }}{2}e^{{ - \frac{{r^{4} }}{{r_{0}^{4} }}}} } \right)^{{ - \frac{1}{2}}} } \right]e^{{ - \frac{{3r^{4} }}{{r_{0}^{4} }}}} \) and \( \beta_{4} = \mathop \int \limits_{0}^{\infty } r{\text{d}}r\left( {1 + \frac{{a_{0}^{2} }}{2}e^{{ - \frac{{r^{4} }}{{r_{0}^{4} }}}} } \right)^{{ - \frac{3}{2}}} e^{{ - \frac{{3r^{4} }}{{r_{0}^{4} }}}} \).

Results and discussion

The differential Eq. (25) for the third harmonic field amplitude has been solved numerically using initial conditions \( F_{3} \) = 0 at \( \varsigma = 0. \)

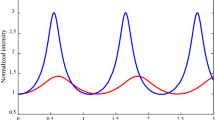

Figure 4 shows the variation of normalized third harmonic field amplitude |F3/E00| with normalized distance of propagation \( \varsigma . \) From Fig. 4, it can be seen that the amplitude of third harmonic power increases linearly with distance. This is due to the reason that for a self-guided beam, the amplitude of the laser remains constant with distance of propagation hence phase matching condition is satisfied for all z and therefore phase matched third harmonic field amplitude scales linearly with z. This can be further justified based on Eq. (25). From this, one obtains the phase mismatch as \( q = k_{3} - 3k - \Delta k \) where \( \Delta k = i\frac{{k_{0} \sqrt 3 }}{{k_{3} \surd \pi }}\left( {1 + \frac{{\omega_{p0}^{2} }}{{c^{2} \gamma_{0} }}\beta_{3} } \right) \) is very small and hence, F is linear function of z. As we increase the amplitude of the laser beam, the harmonic yield increases. The harmonic spectrum for the case of a super-Gaussian laser beam is much broader than that of Gaussian beam. Kaur et al. [16] have studied the resonant third harmonic generation in ripple density plasma for a Gaussian laser beam for the following set of parameters \( \omega r_{0} /c = 70, a_{0} = 0.1, \frac{{\omega_{p}^{2} }}{{\omega^{2} }} = 0.11 \) at normalized propagation distance of 1.5 and obtained conversion efficiency of 0.006%.

Figure 5 shows the variation of \( qc/\omega_{p0} \) with \( \omega /\omega_{p0} \). It is seen that phase mismatch decreases with increase in laser frequency. This can be explained based on the refractive index which is a function of laser frequency in plasma. At higher laser frequency, the refractive index reaches nearly unity; hence, the dispersion effects and phase mismatch decrease. The phase mismatch decreases with the increase in the amplitude of the laser beam.

Conclusions

The depressed electron density channel created by a super-Gaussian laser beam facilitates self-guiding of the beam. The axial intensity of the self-guided beam increases on reducing its spot size. At sufficiently smaller spot size, normalized laser amplitude becomes large and complete electron evacuation occurs from the axial region. For harmonic generation, one must limit laser amplitude below this value. The density ripple plays a crucial role in phase matching. At higher laser intensity, one requires ripple with smaller wave amplitude to account for phase mismatch between the laser and third harmonic. Under phase matched condition, third harmonic field increases linearly with distance. For a super-Gaussian beam of larger spot size (hence smaller axial intensity), the third harmonic amplitude goes as the cube of the amplitude of the laser. However, with beams of smaller spot size (and larger intensity), the electron density in the channel decreases substantially. Hence, the third harmonic power goes slower than the cube of laser intensity.

References

Banerjee, S., Vanelzula, A.R., Shah, R.C., Makimcheck, A., Umstadter, D.: High harmonic generation in relativistic plasma interaction. Phys. Plasmas 9, 2393 (2002)

Grebogi, C., Tripathi, V.K., Chen, H.H.: Harmonic generation of radiation in a steep density profile. Phys. Fluids 26, 1904 (1983)

Liu, X., Umstadter, D., Ting, A., Esarey, E.: Harmonic generation by intense laser pulse in neutral and ionized gases. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 21, 90–94 (1993)

Sprangle, P., Esarey, E., Ting, A.: Nonlinear theory of intense laser plasma interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 2011–2014 (1990)

Malik, A.K., Malik, H.K.: Tuning and focusing of terahertz radiation by DC magnetic field in a laser beating process. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 49, 232–237 (2013)

Malik, H.K.: Terahertz radiation generation by lasers with remarkable efficiency in electron–positron plasma. Phys. Lett. A 379, 2826–2829 (2015)

Rax, J.M., Fisch, N.J.: Third harmonic generation with ultrahigh-intensity laser pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 69, 772–775 (1992)

Parashar, J., Pandey, H.D.: Second harmonic generation of laser radiation in a plasma with a density ripple. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 20, 996–999 (1992)

Rax, J.M., Fisch, N.J.: Phase matched third harmonic generation in plasma. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 21, 105–109 (1993)

Lin, M.W., Chen, Y.M., Pai, C.H., Kuo, C.C., Lee, K.H., Wang, J., Chen, S.Y., Lin, J.Y.: Programmable fabrication of spatial structures in a gas jet by laser machining with a spatial light modulator. Phys. Plasmas 13, 110701 (2006)

Kuo, C.C., Pai, C.H., Lin, M.W., Lee, K.H., Lin, J.Y., Wang, J., Chen, S.Y.: Enhancement of relativistic harmonic generation by an optically preformed periodic plasma waveguide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 033901 (2007)

Malik, H.K.: Density bunch formation by microwave in a plasma filled cylindrical waveguide. Europhys. Lett. 106, 55002 (2014)

Liu, C.S., Tripathi, V.K.: Third harmonic generation of a short pulse laser in a plasma density ripple created by a machining beam. Phys. Plasmas 15, 023106 (2008)

Dahiya, D., Sajal, V., Sharma, A.K.: Phase matched second and third harmonic generation in plasma with density ripple. Phys. Plasmas 14, 123104 (2007)

Kaur, S., Sharma, A.K.: Resonant third harmonic generation in a laser produced thin foil plasma Phys. Plasmas 15, 102705 (2008)

Kaur, S., Yadav, S., Sharma, A.K.: Effect of self-focusing on resonant third harmonic generation of laser in a rippled density plasma. Phys. Plasmas 17, 053101 (2010)

Singh, A., Walia, K.: Self-focusing of Gaussian laser beam through collisionless plasmas and its effect on second harmonic generation. J. Fus. Energy 30, 555–560 (2011)

Walia, K., Singh, A.: Effect of self-focusing of gaussian laser beam on second harmonic generation in relativistic plasma. J. Fus. Energy 33, 83–87 (2014)

Singh, M., Gupta, D.N.: Relativistic third-harmonic generation of a laser in a self-sustained magnetized plasma channel. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 50, 491–496 (2014)

Singh, A., Gupta, N.: Second-harmonic generation by relativistic self-focusing of cosh-Gaussian laser beam in underdense plasma. Laser Part. Beams 34, 1–10 (2016)

Gill, R., Singh, D., Malik, H.K.: Multifocal terahertz radiation by intense lasers in rippled plasma. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 11, 103–108 (2017)

Purohit, G., Rawat, P., Gauniyal, R.: Second harmonic generation by self-focusing of intense hollow Gaussian laser beam in collisionless plasma. Phys. Plasmas 23, 013103 (2016)

Devi, L., Malik, H.K.: On validity of paraxial theory for super-gaussian laser beams propagating in a plasma. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 11, 165–170 (2017)

Singh, D., Malik, H.K.: THz generation by mixing of two super- Gaussian laser beams in collisional plasma. Phys. Plasmas 21, 083105 (2014)

Malik, H.K., Malik, A.K.: Strong and collimated terahertz radiation by super-Gaussian lasers. Europhys. Lett. 100, 45001 (2012)

Acknowledgements

Lalita Devi would like to thank CSIR, Govt. of India for the financial support for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Devi, L., Malik, H.K. Resonant third harmonic generation of super-Gaussian laser beam in a rippled density plasma. J Theor Appl Phys 12, 265–270 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40094-018-0305-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40094-018-0305-0