Abstract

The synthesis of ultra-long high-quality zinc sulfide (ZnS) nanowires of uniform size on heterogeneous substrates is highly desirable for investigating the fundamental properties of ZnS nanowires and for fabricating integrated functional nanodevices. The present study developed a novel technique for growing ultra-long ZnS nanowires on thin-catalyst-coated substrates. ZnS nanowires were synthesized by chemical vapor deposition on a silicon substrate deposited by gold (~ 5 nm in thickness) as the catalyst at 550, 600, 700, 750 and 800 °C. The structural properties of the samples were investigated by X-ray diffraction, and the results showed that the fabricated nanowires have both wurtzite and zinc blend structures. The morphological properties of the nanowires were determined by scanning electron microscopy, and the results show that the substrate is thoroughly coated with 10 µm of zinc sulfide nanowires. Increasing the substrate temperature from 600 to 800 °C increased the diameter of the nanowires and decreased the length. The growth mechanism of the nanowires was vapor–liquid–solid. The EDX spectra of this sample showed an absence of contamination, confirming the high purity of the ZnS nanowires.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Semiconductor nanostructures have attracted great interest for studding the quantum confinement effect and thermodynamic structures of these materials [1,2,3]. Varieties of physical properties such as mechanical strength, plasticity [4], melting [5, 6],sintering and alloying ability [7], diffusivity [8], chemical reactivity [9], as well as the mode of crystal growth (self-assembly) [10], have been found dependent upon particle size. Zinc sulfide (ZnS) with a wide direct optical band gap (Eg ~ 3.72 eV) for cubic zinc blend (ZB) and Eg ~ 3.77 eV for hexagonal wurtzite (WS) phase is an important II–VI semiconductor with a number of interesting properties. Nanostructured zinc sulfide materials have been intensively studied due to their wide potential applications in high-performance devices, such as optoelectronics, sensors, transducers and biomedical sciences [11]. As a one-dimensional nanostructure, ZnS has been synthesized as nanowires, nanobelts and nanocombs [12]. One of the most attracting features of nanowires (NWs) is that lattice mismatch or strain in NWs can be significantly relaxed due to their high surface/volume ratio and small lateral size. Different synthetic approaches have been used for the synthesis of ZnS nanomaterial, especially nanowires and nanorods; these methods include laser ablation [13], vapor transport in the presence [14] or in the absence of [15] catalyst, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [16], electrochemical deposition [17] and solvothermal method [18]. Among them, CVD has got a number of advantages such as simplicity and the ability to use a wide variety of precursors such as liquid precursors, gaseous precursors, solid precursors which include halides, hybrids, metal–organic and organic. It also enables the usage of a variety of substrates and allows materials growth in a variety of forms, such as powder, thin or thick films aligned or entangled straight or coiled nanotubes. It also offers better control on the growth process of materials [19]. CVD allows proper control on the deposition rate and pressure temperature so as to prepare and maintain the desired structure, composition and size of the materials. Growth of nanowires via the vapor–liquid–solid (VLS) mechanism is an effective method, in which the diameter and length of nanowires are also affected by other growth conditions such as the growth ratio and temperature. [20]. In ZnS nanowire preparation by VLS, a thin layer of Au is used as the catalyst by thermal evaporation of ZnS powder [21]. However, separate evaporation of sulfur and zinc powder for ZnS nanowire preparation, which is more controllable by sulfur activity, is rarely reported. In the present work, we have preferred this route of synthesis and successfully prepared very long ZnS nanowires.

Experimental

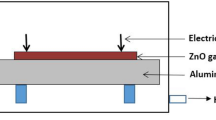

The ZnS nanowires were synthesized by vapor–liquid–solid (VLS) technique. The conventional VLS mechanism is based on evaporation of the source material and transfer of the vapor to lower-temperature regions using an inert gas as a carrier. The experimental setup (CVD system in Fig. 1) consisted of a horizontal tube furnace (6 cm in diameter; 50 cm in length) with a temperature control unit, a horizontal quartz tube (4.5 cm in diameter; 102 cm in length 102), two alumina boats, a rotary vacuum pump, 5-nm-thick Au-coated n-type Si (with a preferential plane of 400) substrates and Ar gas as the carrier gas with a gas flow control system and a barometer. The alumina boat containing sulfur powder (1 g, 99% purity; Merck) and the boat containing granular zinc (0.8 g; 99.9% purity; Merck) were kept at 140 and 950 °C, respectively. The Au-coated Si substrates were kept at 550, 600, 700, 750 and 800 °C in the center of the furnace. One terminal of the quartz tube was connected to a vacuum pump and gas flow system. The rotary vacuum pump evacuated the tube to a base pressure of 5 × 10−2 mbar.

After closing the rotary pump, the tube was filled with high-purity Ar gas to eliminate any O2 in the tube, and the furnace was turned on to heat up. When the furnace reached the process temperature (950 °C), the terminal opposite to the gas flow system opened and was kept open during the process to allow the gas to flow out at a rate of 50 SCCM (sample A) and 80 SCCM (sample B). The pressure inside the tube was increased to ~ 2×10−1 mb, and the Ar carrier gas was fed into it. The values for flow rate and dynamic vacuum were kept constant until the end of the experiment. The surface morphology of the nanowires was investigated by means of SEM. To investigate the chemical composition of the ZnS nanowires, elemental analysis of the samples was performed using energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy.

Results and discussion

Three distinct stages existed in the catalyst-assisted growth of ZnS nanowires. In the first stage, the Au film-coated Si substrate is annealed at ~ 700 °C. The Au film aggregated to form small islands because of the liquid-like mobility of the Au atoms at high temperature. In the second stage, called alloying and nucleation, the islands were exposed to Zn vapor carried in Ar gas and reacted with the vapor to form an Au–Zn alloy of increased volume. At 950 °C, the vapor pressure of zinc was > 103 mbar, which was much greater than the sulfur vapor pressure at 140 °C of ~ 10−1 mbar and system pressure of 2 × 10−1 mbar.

Sulfur vapor and Zn vapor were continuously absorbed by alloy droplets and reacted with each other inside the droplet until zinc sulfide reached supersaturation. At this stage, the ZnS precipitated in the interface with the substrate and alloy droplets to form zinc sulfide nanocrystals. Next, ZnS nanowires were grown with Au nanoparticles in top of them. It can be said that the ZnS nanowire growth mechanism was VLS. It can be seen that the size and position of the catalyst relate to the diameter and position of the nanowires, as the liquid phase was confined to the area of the precipitated solid phase. Figure 2 shows SEM images of samples A and B at a substrate temperature of 550 °C. A low Ar flow rate (50 SCCM) in Fig. 2a produced no wire, but formed nanoflowers. At a higher gas flow rate in Fig. 2b, both long straight rods and shapeless structures formed.

Figure 2c is a sample prepared under the same conditions as in Fig. 2a with the addition of a substrate at 600 °C. This shows that the synthesized products consisted of a small quantity of nanowires with diameters of about 60–100 nm and a length of several µm along with nanocombs and tetrapodal nanostructures.

The chemical potential of the component in the metal alloy catalyst increased as the size of the catalyst decreased because of the Gibbs–Thomson effect. Dissolving a vapor component into a liquid alloy became increasingly difficult as the size decreased, making it difficult to reach a sufficient supersaturation state to induce the growth of nanowires. It is known that the growth of nanowires with diameters of more than > 10 nm is feasible; however, growing those < 10 nm in size is difficult because of the thermodynamic limitation associated with the use of a catalyst.

Figure 3a, c, e shows that the substrate was densely covered with randomly oriented nanowires. The diameters of the nanowires grown at 700, 750 and 800 °C were about 70–120, 80–160 and 100–190 nm, respectively. Under high magnification, the SEM images of these samples (Fig. 3b, d, f) show Au nanoparticles on the tips of the nanowires in a VLS growth mechanism. An increase in growth temperature increased the average diameter of the ZnS nanowires grown on the Si substrates, and their average length decreased. Very long ZnS nanorods of > 10 µm can be seen in all SEM images; however, straight rods were more abundant in the image in Fig. 3e than in 3a. As the substrate temperature increased to 800 °C, a change from nanowires to nanorods occurred. In this mechanism, substrate temperature was the critical experimental parameter influencing the morphology and size of the nanostructures.

According to the VLS mechanism, the size of the Au nanoparticles plays a significant role in determining the length and diameter of the ZnS nanowires. The reports show that as the substrate temperature increases, the merging of Au nanoparticles increases [12]. It appears that the increase in average diameter and the decrease in average length relate to the increase in the diameter of Au nanoparticles.

The XRD patterns of nanowires grown on a Si substrate coated with Au film at 550, 600 and 700 °C demonstrate the temperature dependence of formation of ZnS nanowires (Fig. 4). The results indicate that an increase in growth temperature increased the content of the wurtzite phase of nanowires grown on Si substrate. This is evident in the intensity of the (101) and (100) peaks of ZnS relative to the (200) peak of Si. The ZnS nanowires consisted of a matrix of hexagonal and cubic stacking of the Zn–S layers according to standard cards (00-005-0492) and (00-002-0565), respectively.

Diffraction peaks with 2θ values of 28.50, 47.50 and 56.30 related to the (111), (220) and (311) of the cubic phase of ZnS appeared. Moreover, XRD peaks at 2θ values of 26.90, 30.50, 39.6 0 and 51.7 0 related to reflection from the (100), (101), (102) and (103) planes of wurtzite ZnS also appeared. The peak at 2θ of 32.90 relates to the Bragg reflection from the (200) plane of the silicon substrate. Two other features at 2θ values of 38.20 and 44.40 relate, respectively, to the (111) and (002) planes of the Au catalyst.

The small difference in Gibbs free energy [14] facilitates the phase transformation and is very sensitive to the reaction parameters. As the substrate temperature was quite high, both phases of the ZnS nanostructures were created in the mixture. The II–VI NWs entwined with the mixed ZB/WS structures can be commonly observed along the (111) direction, such as ZnS, [22] ZnSe [23] and ZnTe [24]. It is known that the cubic to hexagonal phase transformation takes place at a temperature of < 1020 °C, which is the cubic–hexagonal phase transition temperature of bulk ZnS.

It is interesting to note that no ZnO-related peaks were observed in the XRD patterns. A peak denoting Au2S [depicted as (002) at a 2θ of 44.5] was observed. Quantitative analysis shows that the quantity of this phase dropped significantly with an increase in annealing temperature of the Au catalyst from 550 to 700 °C. It appears that the temperature dependence of energy of the Au catalyst and host caused a considerable drop in the concentration of the catalyst during the growth of the ZnS nanowires. This compound perhaps forms on the surface of the nanowires. The EDS spectra showed that S and Zn had atomic ratios of 42–58% (Fig. 5). Other peaks in the spectra relate to the Au-coated Si substrate.

Conclusion

A novel successive multistep growth method was developed to synthesize very long ZnS nanowires of several hundred µm in length. A systematic study was carried out to determine the optimal parameters affecting the dimensions of the nanowires synthesized on a large scale. Ultra-long ZnS nanowires were grown successfully through thermal evaporation of zinc and sulfur powder at 600–800 and 140 °C, respectively. The ZnS nanowires were grown with a mixture of zinc blend and wurtzite structures. In VLS deposition, adjusting the synthesis conditions controls the formation of ZnS nanostructures as nanoflowers, nanowires and nanorods. Increasing the substrate temperature from 600 to 800 °C increases the nanowire diameter and decreases their length. The abundance of wurtzite structures in the mixture increased as the substrate temperature increased. XRD data analysis [as per the ratio of (100)–(002) peaks at different substrate temperatures] confirms that a cubic to hexagonal phase transformation has taken place at a lower temperature than that for bulk ZnS.

References

Sheng, X., Gautam, U.K., Bando, Y., Dierre, B., Sekiguchi, T., Golberg, D.: Multiangular branched ZnS nanostructures with needle-shaped tips: potential luminescent and field-emitter nanomaterial. J. Phys. Chem. C 112(12), 4735–4742 (2008)

Ma, L.A., Wei, Z.H., Ye, X.Y., Lin, J.Y., Hu, L.Q., Guo, T.L.: Morphology-controlled synthesis and field-emission properties of patterned SnO2 nanostructures with different morphologies. Ceram. Int. 43(8), 6096–6104 (2017)

MaZ, L.A., Wei, H.: Field emission properties of crystalline-SnO2 (core)/amorphous-SnO2 (shell) nanowire arrays on carbon paper. Mater. Lett. 213, 257–261 (2018)

Kudinova, N.R., Polyanskiy, V.A., Polyanskiy, A.M., Yakovlev, Y.A.: Modeling of the plasticity of microstructured and nanostructured materials. St. Petersb. Polytech. Univ. J. Phys. Math. 1(4), 405–409 (2015)

Nabeel Dhaidan, S.: Nanostructures assisted melting of phase change materials in various cavities. Appl. Therm. Eng. 111, 193–212 (2016)

Li, X.L., Wang, C.X., Yang, G.W.: Thermodynamic theory of growth of nanostructures. Prog. Mater Sci. 64, 121–199 (2014)

Mintova, S., Olson, N.H., Valtchev, V., Bein, T.: Mechanism of zeolite a nanocrystal growth from colloids at room temperature. Science 283, 958–960 (1999)

So Espen, S., Anders, D.B., Bo, B.B., Iversen, B.: Tailoring band gap and thermal diffusivity of nanostructured phase-pure ZnAl2O4 by direct spark plasma sintering synthesis. J. Solid State Chem. 256, 45–52 (2017)

Sayle, T.X.T., Sayle, D.C.: Visualizing the enhanced chemical reactivity of mesoporous Ceria; simulating templated crystallization in silica scaffolds at the atomic level. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136(10), 4056–4065 (2014)

Berbezier, I., De Crescenzi, M.: Self-assembly of nanostructures and nanomaterials. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 6, 1397–1398 (2015)

Wu, P., He, Y., Wang, H.F., Yan, X.P.: Conjugation of glucose oxidase onto Mn-doped ZnS quantum dots for phosphorescent sensing of glucose in biological fluids. Anal. Chem. 82(4), 1427–1433 (2010)

Fang, X., Zhai, T., Gautam, U.K., Li, L.G., Wu, L., Bando, Y., Golberg, D.: ZnS nanostructures: from synthesis to applications. Prog. Mater Sci. 56, 175–287 (2011)

Jiang, Y., Meng, X.M., Liu, J., Hong, Z.R., Lee, C.S., Lee, S.T.: ZnS nanowires with wurtzite polytype modulated structure. Adv. Mater. 13, 1195–1198 (2003)

Meng, X.M., Liu, J., Jiang, Y., Chen, W.W., LeeI Bello, C.S., Lee, S.T.: Structure- and size-controlled ultrafine ZnS nanowires. Chem. Phys. Lett. 382, 434–438 (2003)

Yang, Y., Zhang, W.: Preparation and photoluminescence of zinc sulfide nanowires. Mater. Lett. 58, 3836–3838 (2004)

Zhang, H., Zhang, S., Zuo, M., Li, G., Hou, J.: Synthesis of ZnS nanowires and assemblies by carbothermal chemical vapor deposition and their photoluminescence. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 47–50 (2005)

Xu, X.J., Fei, G.T., Yu, W.H., Wang, X.W., Chen, L., Zhang, L.D.: Preparation and formation mechanism of ZnS semiconductor nanowires made by the electrochemical deposition method. Nanotechnology 17, 426–429 (2006)

Chai, L., Du, J., Xiong, S., Li, H., Zhu, Y., Qian, Y.J.: Synthesis of quartzite ZnS nanowire bundles using a solvothermal technique. Phys. Chem. C 111, 12658–12662 (2007)

Wang, C., He, Y., Peng, C., Wang, S., Liu, X.: Controllable synthesis of Ni-catalyzed tetragonal tungsten nanowires via chemical vapor deposition. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 22(5), 514–519 (2012)

Zhu, G., Zhou, Y., Wang, S., Yang, R., Ding, Y., Wang, X., Bando, Y., Lin Wang, Z.: Synthesis of vertically aligned ultra-long ZnO nanowires on heterogeneous substrates with catalyst at the root. Nanotechnology 23, 055604–055609 (2012)

Lin, M., Sudhiranjan, T., Boothroyd, C., Ping Loh, K.: Influence of Au catalyst on the growth of ZnS nanowires. Chem. Phys. Lett. 400, 175–178 (2004)

Hao, Y., Meng, G., Wang, Z., Ye, C., Zhang, L.: Periodically twinned nanowires and polytypicnanobelts of ZnS: the role of mass diffusion in vapor–liquid–solid growth. Nano Lett. 6, 1650 (2006)

Wang, Y., Phillpose, U., Xu, T., Ruda, H., Khavanagh, K.: Twinning modulation in ZnSe nanowires. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 22, 175 (2007)

Meng, Q., Jiang, C., Mao, S.: Temperature-dependent growth of zinc-blende-structured ZnTe nanostructures. J. Cryst. Growth 310, 4481 (2008)

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to acknowledge from Imam Khomeini international university for their financial help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Khanlary, M.R., alijarahi, S. & Reyhani, A. Growth temperature dependence of VLS-grown ultra-long ZnS nanowires prepared by CVD method. J Theor Appl Phys 12, 121–126 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40094-018-0289-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40094-018-0289-9