Abstract

In aeronautical and automotive industries the use of rivets for applications requiring several joining points is now very common. In spite of a very simple shape, a riveted junction has many contact surfaces and stress concentrations that make the local stiffness very difficult to be calculated. To overcome this difficulty, commonly finite element models with very dense meshes are performed for single joint analysis because the accuracy is crucial for a correct structural analysis. Anyhow, when several riveted joints are present, the simulation becomes computationally too heavy and usually significant restrictions to joint modelling are introduced, sacrificing the accuracy of local stiffness evaluation. In this paper, we tested the accuracy of a rivet finite element presented in previous works by the authors. The structural behaviour of a lap joint specimen with a rivet joining is simulated numerically and compared to experimental measurements. The Rivet Element, based on a closed-form solution of a reference theoretical model of the rivet joint, simulates local and overall stiffness of the junction combining high accuracy with low degrees of freedom contribution. In this paper the Rivet Element performances are compared to that of a FE non-linear model of the rivet, built with solid elements and dense mesh, and to experimental data. The promising results reported allow to consider the Rivet Element able to simulate, with a great accuracy, actual structures with several rivet connections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Riveting is one of the most widely used technology for joining laminar structures in industrial sectors, where objectives of lightness and multiple spot connections distribution are solved.

The rivet represents an optimal solution when thin sheets are connected and substitutes welding technologies in case of lightweight alloys that are hardly weldable. The region close to the rivet presents complex three-dimensional strain and stress distributions with high gradients and values. For a correct evaluation of these fields in a numerical modelling, detailed FE models with dense meshes are needed. At the same time, it must be considered that in real structures several hundreds of rivets are present and it is required to reduce the number of degrees of freedom to contain the computational commitment. In these cases it is crucial to introduce modelling techniques that reduce the computational time, without introducing drastic simplification with consequent loss in accuracy of results, in terms of local stiffness evaluation.

As a matter of fact, the connection between rivet and laminate can be modelled with FE models presenting 3D dense meshes and contact elements (Urban 2003; Al-Emrani and Kliger 2003) obtaining a high accuracy in local results, but at the same time very large calculation times when multi-joined parts are studied.

To reduce the computational commitment, it is mandatory to reduce the number of degrees of freedom of the joint FE model, substituting the 3D mesh with mono-dimensional elements, such as links or beams. In Xiong and Bedair (1999) and Ho and Chau (1997) the authors use gap and spring elements, whose stiffness and results interpretation is based on analytical reconstructions of the structural behaviour. With these modelling techniques it is possible to obtain the global behaviour of the structure, but losing in accuracy of local stiffness evaluation.

In Hanssen et al. (2010) another important application of simplified rivet modelling is presented, where spot connections are implemented in explicit FE analysis of crash phenomena. In this case, the connector element is able to describe a self-piercing rivet behaviour until the failure.

In the subsequent paper, Hoang et al. (2012) investigate the structural behaviour of T-components made by joining two aluminium extrusions using aluminium self-piercing rivets and checking the capability of the previous SPR model proposed for large-scale shell analyses.

The fatigue estimation of rivet connection can be obtained by combining FE models with theoretical approaches, suitable criteria and experimental evidences. As an example, in Kang and Kim (2015) it is proposed a 3D FE model of SPR mounted in different specimen typologies characterized by different loading conditions on rivets. Using FE analyses, validated through experimental comparison, the authors demonstrated the influence of the applied load typology on failure mode and on fatigue life. Nevertheless, the results are obtained by introducing multi-axial criterions, based on local stresses evaluation, reachable only with 3D refined models; this makes the approach of difficult application in multi-riveted structures.

The modified detail fatigue rating method (DFR method) proposed in Huang et al. (2012) represents a reliable approach for fatigue life prediction; however, its accuracy is sensible to the correct detection of stress concentration factor through FE analysis, uninsured with simplified models.

Some simplifications to rivet geometry is proposed in Skorupa et al. (2015) to apply Neuber fatigue notch factors to open hole and filled hole subjected to remote tension, pin loading and out-of-plane bending. The experimental validation revealed the necessity of implementing the stiffening due to riveting process, neglected by the simplifications.

However, in case of fatigue life prediction, whatever the used approach, the priority is the correct evaluation of local joint stiffness that drives to the real distribution of loads on every single joint (especially in a multi-connected structure). In fact, once known, the actual loads on the single joint it is possible to correctly introduce suitable criteria or approaches for fatigue life estimation.

A joint model that combines a reduced number of degrees of freedom (dof) with a good accuracy of local stiffness evaluation, based on a theoretical solution of the region near to the rivet, has been proposed in Vivio (2007) and improved in Vivio (2009). The rivet is modelled with an assembly of one-dimensional elements, whose stiffness is computed analytically with a closed-form solution of a theoretical model of the rivet connection region, considered as a circular plate with a central rigid region. The so-called Rivet Element (RE) can be inserted in a generic jointed structure, modelled with shell elements, introducing a very small number of dof; on the other hand, the improvements in accuracy of results is relevant (Vivio 2009). The RE modelling technique follows the same approach already consolidated in spot-weld modelling technique, performed both in elastic (Vivio 2009) and elastic plastic conditions (Fanelli and Vivio 2009, 2015). As proposed in Fanelli et al. (2012), friction stir spot welds too can be analyzed with same approach.

In this paper, the structural behaviour of different geometries of lap-shear riveted joint have been investigated numerically and experimentally and RE modelling has been validated; the element parameters have also been calibrated using a very refined non-linear 3D model of rivet. Then, numerical values of the parameters, that represent the best estimate of joint stiffness, have been identified.

Rivet Element definition

The RE presented in Vivio (2009) consists of a series of beam tapered, having suitable elastic characteristics, radially disposed in plane with the metal sheets and centrally connected. Elements stiffness comes from a structurally equivalent modelling of the junction considered as a circular plate with a central rigid inclusion, which simulates the core of the rivet. The annular plate is elastically connected with the rigid inclusion, at the inner radius, and is clamped at the outer radius.

This theoretical bi-dimensional reference model (Fig. 1) is solved in closed form by integration of elliptic equations, when the plate is loaded by in-plane and out-plane loads. The nugget is subjected to in plane load T, out of plane bending moment M and orthogonal load P (Fig. 1); u, v and w are the displacements in x, y, z directions, respectively, and r the radial position variable; r i and r e are the inner and outer radiuses of the sheet and t is the thickness of the plate.

In the rivet model the relative inclination between central rigid nugget and plate (along circumferential direction) is allowed by the introduction of an elastic revolute joint that offers a partial resistance in terms of radial moment. This moment share is expressed by a parameter, named κ, that assumes values between 0 and 1 and permits to tune the elastic connection between the stalk of rivet and the plate of the joints (Vivio 2009).

A null value of κ parameter corresponds to a loose rivet connection while a value equal to 1 corresponds to a clamping, like the spot weld behaviour. For every actual rivet connection an intermediated value of κ parameter can be found with a calibration of RE model with experimental characterizations or FE refined models. This procedure can be performed for every rivet type and considering different technological parameters and actual assembly conditions.

The ζ parameter pre-multiplies the in-plane stiffness value assigned to the RE and reducing it proportionally (0 < ζ ≤ 1). It reports the local in-plane interactions of rivet with plate, such as contact stiffness, in terms of global effect. The ζ parameter value is proper for the coupling of the rivet with the sheet and depends to rivet type and assembly conditions; also for this parameter, a calibration with experimental data or validated reference FE models is necessary.

As demonstrated in Vivio (2007, 2009), friction between plate and rivet has a relevance on local stress distribution and a negligible role on local stiffness contribution, so that in RE it is not accounted.

The link element that connects the radial beams assembly (one for each metal sheet) simulates the mechanical behaviour of the actual rivet stalk. A damage of the rivet can be considered by introducing with a weakening of link characteristics, even with a progressive decrease until failure of the rivet. This approach has been applied and verified for spot welds in Salvini et al. (2009).

The failure of the rivet corresponds to link disappearance.

A promising application of RE together with a DFR approach for fatigue reliability estimation can be found in Di Cicco et al. (2017).

Comparison 3D fem: RE model and experimental data

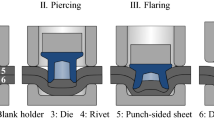

To demonstrate the accuracy of RE, we applied the Rivet Element approach to an actual case considering a typical aeronautic joint, as Cherrymax blind rivet (Fig. 2). In this section, the results obtained using RE, in terms of structural stiffness, are presented and compared with those of a 3D model of the rivet and those coming from experimental tests. The 3D model has been built up with 8-nodes solid elements and 3 dofs per node. The high number of dofs and the type of elements assure high accuracy of simulations, so that we will call this model FullFEM from now on.

The geometry of the rivet has been modelled with slight simplifications to head and buck-tail, whose radial values are 9.5 and 6 mm, respectively. No gap is modelled between rivet shank and plate hole. In fact the nominal actual gap is completely annulled by local plastic strains in assembly phase. By analysing results of preliminary analyses, we confirmed the negligible effect of these residual local stresses to global stiffness evaluation. It permitted us to not to take into account assembly strains and close the gap in FullFEM. The central stalk is modelled in steel as the actual Cherrymax rivet. The sheet region far from the rivet has been modelled with shell elements with 4 nodes and 6 dofs per node and connected to solid elements with constraint equations that guarantee displacements and rotations compatibility between interfaces.

The portion of the plates nearby the rivet is modelled with solid elements and contact elements are considered on surfaces facing plates and between plates and rivet, considering Coulomb model for friction (f = 1.1).

The mounting pre-load of the rivet has been introduced imposing an interference i = 0.05 mm, between the head of the rivet and upper plate, to be suppressed by contact elements. This leads to an axial load of 50 MPa on the rivet and a compression on plates. The value of pre-load has been evaluated with preliminary analyses.

The lap-shear specimen is loaded along x-axis on one end, where only the displacement along x-axis is allowed (Fig. 3), while at the other end it is clamped.

The FE model with RE model (REM) of the lap-shear specimen (Fig. 3) is defined with shell elements with 4 nodes and 6 dofs per node. To define RE calibration, we performed several simulations with different values of κ and ζ. Starting from any existing mesh, the RE substitutes a region of shell elements with the radial series of beams. In this case a square with side L = 20 mm (Fig. 3) is the sheet portion where RE has been applied.

Both FullFEM model and REM were subjected to tensile tests reproducing the experimental campaign, described below. The loads applied are very low because the interest is focused on the rivet characterization in the elastic field, for this reason an elastic material (an aluminium alloy with Young modulus E = 72.8 GPa, Poisson ratio ν = 0.33) is considered for REM elements. Nevertheless, very local plasticization can be present in FullFEM solid element. An elastic with perfect plastic behaviour is assigned to the material in FullFEM with the same elastic characteristics of REM and a yield stress of 270 MPa. The characterization of the junction is performed for very low loads applied, so small displacement and strain are considered. In spite of this, the presence of contact element leads to a non-linear analysis.

Tensile tests have been carried out on aluminium lap-shear specimens (Young modulus E = 72.8 GPa, Poisson ratio ν = 0.33) with the geometry shown in Fig. 4. The specimen were tested in an Alliance MTS Insight 100 material testing system that comprised a load frame, electronic frame controller, a 100 kN capability load cell, TestWorks® software and a MTS 634.12F-5X extensometer. In the experiments, the specimens were pulled in traction between parallel grips under force control (Fig. 5a) in quasi-static conditions (very low load increment vs. time).

An axial extensometer measured the stiffness on x-axis of the riveted junction collecting the relative displacement (called ΔU x ) of two points 76 mm far from each other on rivet opposite sides. The clamping zone is extended for 50 mm. The Cherrymax blind rivet (Fig. 5b) has an aluminium sleeve (QQ-A-430, E = 72.4 GPa, ν = 0.33) and a steel stem (AMS 6322, E = 205 GPa, ν = 0.29) with a diameter of 5.1 mm. Tensile tests carried out on the single rivet revealed that the failure load is 7000 N.

The experimental investigation consists of three different geometries of lap-shear specimen, respectively called α, β and γ, each of which was evaluated for two different thicknesses (t1 = 1.2 mm and t2 = 1.5 mm). Geometrical characteristics of specimens are synthetized in Table 1. To evaluate the stiffness behaviour of the riveted joint, the test has been performed with a different load for each type of specimen geometry.

Type α specimen

Different load have been applied to the specimen having different thickness: 700 N for t1 thickness and 900 N for t2 thickness. Different values of ζ and κ parameter have been considered in the RE modelling. For reason of clarity only the most fitting values are reported.

The averaged error between RE model and FullFEM results is shown in Table 2, in terms of relative displacements ΔU x and rivet rotation along y-axis (ϕyriv) for both thicknesses. Results corresponding to most relevant values of ζ and κ parameter have been reported. In Fig. 6, the trend of relative displacement ΔU x is shown as function of applied load, comparing numerical results and experimental data for both thicknesses for a fixed ζ = 0.2. In Table 2 variation of the rotation due to ζ was not considered because this parameter has no effect on y-rotation. The most fitting value of ζ is 0.2, while the best value of κ is 0.4.

It has to be noted that the stiffness of the junction is slightly influenced by contact phenomena, clearance and friction values since in Fig. 6 the experimental displacement–load trend is almost linear. In case of thickness t1 the FullFEM model fits well the experimental data, while in case of thickness t2 the stiffness of the joint is underestimated probably because of the choice of the interference i, that has been chosen the same for both thickness cases.

Figures 7 and 8 shows the behaviour of relative displacements ΔU x of FullFEM and RE modelling at 400 N for specimens with thickness t1 and t2, respectively, with variable κ and fixed the best value of ζ = 0.2, according to previous results. The comparison with experimental measurements evidences a good reliability of FullFEM and RE modelling for κ equal to 0.4 in case of thickness t1 while for thicker plates the best fitting value seems like κ equal to 1.

It has to be noted that Fig. 8 represents a stiffness condition for a fixed value of load, while the actual behaviour of the joints is not linear, albeit slightly. The suggested value of κ (equal to 0.4) is best fitting value for the stiffness trend at increasing load.

Type β specimen

Table 1 shows the geometrical characteristics of type β specimen. Also in this case the length of overlap between the plates has been set at 20 mm and the maximum loads applied to the specimens are 700 N for t1 thickness and 900 N for t2 thickness.

Similarly, to the previous specimens, in Table 3 are presented the results in terms of percentage variation concerning the relative x-displacements calculated in the position of the extensometer and percentage variation of rivet rotation along y-axis, for both thicknesses.

Furthermore, a comparison in terms of applied load versus relative displacement is reported in Fig. 9, considering RE and FullFEM numerical results and experimental data.

Figures 10 and 11 shows the behaviour of relative displacements ΔU x of FullFEM and RE modelling at 400 N for specimens with thickness t1 and t2, respectively, considering the variation of κ and having still set the best value of ζ = 0.2, according to previous results. The comparison with experimental measurements confirms the good reliability of FullFEM and RE modelling for κ equal to 0.4 in case of thickness t1 while for thicker plates the best fitting value κ seems to be between 0.4 and 0.6. Nevertheless, this behaviour suggests the single choice of κ = 0.4.

For specimen β is evident a good agreement between experimental data and numerical ones, both from FullFEM and RE modelling. The choice of ζ = 0.2 and κ equal to 0.4 gives values of relative displacement at gage location that perfectly match the averaged experimental values. The FullFEM reliability seems to be less sensible to interference values.

Type γ specimen

Table 1 shows the geometrical characteristics of type γ specimen. Differently from the previous specimen types, in γ specimen the length of overlap between the plates is 30 mm (Table 1). The maximum load is 800 N for t1 thickness and 1000 N for t2 thickness.

In this case a length L = 14 mm of RE has been set in REM. Considering results in Table 4 it is possible to evaluate that the best value of ζ is 0.3 considering specimen with t1 thickness; nevertheless, also in this case the value ζ = 0.2 can be considered as a good compromise, considering all geometries of the γ specimen. Results in Figs. 12, 13 and 14 confirm, also in this case, the good matching of numerical results and experimental data.

The value ζ = 0.2 chosen for the RE model gives to the joint a behaviour slightly compliant in comparison to experimental data, especially in case of thicker plates. This behaviour suggests the use of higher values of κ but even for κ = 0.4, used in previous cases, the error committed by the RE model is still acceptable.

Conclusions

In this paper, Rivet Element capability of structural behaviour simulation is investigated for different geometries of riveted lap-shear specimen. The RE is a FE assembly able to simulate the joint stiffness using a reduced number of dofs. For this reason its application is particularly suitable in case of complex multi-riveted structures. By means of a theoretical reference model of the joint, solved in closed form, acting on κ and ζ parameters it is possible to simulate different types and technologies of rivets. Each manufacturing technique can be characterized by a specific set of these parameters that describes the local stiffness of the rivet.

The presented results from different FE modelling techniques show that the RE model simulates the structural stiffness of the specimen in a comparable way of complex 3D FE models with solid elements. The accuracy of results is combined with a high reduction of dofs implemented and time spent in simulation.

These FE results have been further compared to experimental tests data. The goodness of this comparison evidences the accuracy of the structural equivalence of the reference theoretical model on which is based the RE. Once defined the set of outlined parameters proper of the specific rivet type, the use of RE permits to obtain better results than frequently used simplified single connection FE techniques but with the same computational time consumption.

References

Al-Emrani M, Kliger R (2003) FE analysis of stringer-to-floor-beam connections in riveted railway bridges. J Constr Steel Res 59:803–818

Di Cicco F, Fanelli P, Vivio F (2017) Fatigue reliability evaluation of riveted lap joints using a new rivet element and DFR. Int J Fatigue 101:430–438

Fanelli P, Vivio F (2009) A new analytical model for the elastic–plastic behaviour of spot welded joints subjected to orthogonal load. Int J Solids Struct 46:572–586

Fanelli P, Vivio F (2015) A general formulation of an analytical model for the elastic–plastic behaviour of a spot weld finite element. Mech Res Commun 69:54–65

Fanelli P, Vivio F, Vullo V (2012) Experimental and numerical characterization of Friction Stir Spot Welded joints. Eng Fract Mech 81:17–25

Hanssen AG, Olovsoon L, Porcaro R, Langseth M (2010) A large-scale finite element point-connector model for self-piercing rivet connections. Eur J Mech Solids 29:484–495

Ho KC, Chau KY (1997) An infinite plane loaded by a rivet of a different material. Int J Solids Struct 34(19):2477–2496

Hoang NH, Hanssen AG, Langseth M, Porcaro R (2012) Structural behaviour of aluminium self-piercing riveted joints: an experimental and numerical investigation. Int J Solids Struct 49:3211–3223

Huang W, Wang TJ, Garbatov Y, Soares CG (2012) Fatigue reliability assessment of riveted lap joint of aircraft structures. Int J Fatigue 43:54–61

Kang SH, Kim HK (2015) Fatigue strength evaluation of self-piercing riveted Al-5052 joints under different specimen configurations. Int J Fatigue 80:58–68

Salvini P, Vivio F, Vullo V (2009) Fatigue life evaluation for multi-spot welded structures. Int J Fatigue 31:122–129

Skorupa M, Machniewicz T, Skorupa A, Korbel A (2015) Fatigue strength reduction factors at rivet holes for aircraft fuselage lap joints. Int J Fatigue 80:417–425

Urban MR (2003) Analysis of the fatigue life of riveted sheet metal helicopter airframe joints. Int J Fatigue 25:1013–1026

Vivio F (2007) Modelling rivets in the finite element analysis. SAE technical paper, Society of Automotive Engineering, Warrendale, PA, no 2007-01-1362

Vivio F (2009) A new theoretical approach for structural modelling of riveted and spot welded multi-spot structures. Int J Solids Struct 46:4006–4024

Xiong Y, Bedair OK (1999) Analytical and finite element modeling of riveted lap joints in aircraft structure. AIAA J 1:93–99

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to urisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vivio, F., Fanelli, P. & Ferracci, M. Experimental characterization and numerical simulation of riveted lap-shear joints using Rivet Element. Int J Adv Struct Eng 10, 37–47 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40091-017-0176-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40091-017-0176-7