Abstract

To demonstrate the characteristics of the nonlinear response of steel frames, an elastic dynamic response analysis of the semi-rigid frame is performed under the harmonic wave. The semi-rigid contact is represented by the alternating spring which is given stiffness by a three-parameter energy model which approaches the hysterical curve by hardening model. The properties of spectra and hysteric curves are presented. This study shows that (1) the greater the acceleration input capacitance the smaller the instant connection capability and the smaller is the response. (2) However, by allowing an extreme increase in capacitance input acceleration, response spectra can be increased as the contact stiffness results near zero.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the traditional analysis of the steel frame, the links between the beam and the column are assumed to be either perfectly solid or perfectly hinged.

In traditional analysis of steel frame, beam and column links are supposed to be either perfectly rigid or pinned. The real links which are specially bolted behave intermediate having nonlinear stiffness. Those connections are called semi-rigid connections. To design semi-rigid for limit state design method such as (AISC) specification (1993) for Load and Resistance Factor Design (LRFD), a prediction model on M − θ r curve for each type of connection, a nonlinear analysis method of column stability must be developed. Many researchers have been addressing these issues. The simple design procedure following AISC-LRFD specification for fully rigid frame has been proposed. However, this was based on static analyses (Durucan and Dicleli 2010; Varum et al. 2013).

A more detailed method for steel frame should be considered for dyanmic loads for earthquake load earthquake load that incorporates the seismic design concept. In recent years, the dynamic properties were analyzed by Barsan and Chiorean (1999), Bhatti (2013, 2016a, b), and Vimonsatit et al. (2012) for semi-rigid connections. However, more information on dynamic response characteristics of semi-rigid frames is required for the establishment of a seismic design procedure.

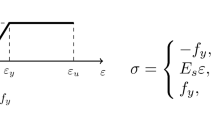

To investigate (1) hysteretic damping effect of nonlinear connection stiffness and (2) the influence of input acceleration amplitude and vibration frequency on dynamic response characteristics of the frame, dynamic analyses for steel frame are performed by inputting sinusoidal acceleration waves at the basement. In these analyses, finite element technique considering nonlinear connection stiffness and geometrical non-linearity is applied. Semi-rigid connections are analyzed and these hysteretic M −θ r curves are approximated by hardening rule, LS-DYNA is used for the analyses (Fig. 1) (Hallquist 1999 and Sekulovic and Nefovska 2008).

Connection modeling

The connections are modeled based on three parameters: shape parameter n, ultimate moment capacity M u, and initial connection stiffness R ki. The moment is calculated as below:

where m is the connection moment (=M/M u), θ is the relative rotation (=θ r /θ 0), and θ 0 is the plastic rotation (=M u/R ki).

Cyclic moment rotation is shown in Fig. 2. The connection is linearly unloaded up to zero connection moment, M = 0, with the connection stiffness being the same as R ki, the same as that at monotonic loading.

Assumptions of numerical analysis

Figure 3 shows a semi-rigid portal frame steel used. The section properties are selected according to AISC-LRFD specification (AISC 1993) and the distributed uniform load w is 20 kN/m for dead. Beam and columns are modeled as beam elements. Distributed load mass of w is replaced as lumped mass. Columns and beam members are elastic such as Young’s modulus E = 206 GPa, density ρ = 7.85 × 103 kg/m3 and Poisson’s ratio ν = 0.3. To numerically investigate dynamic response properties of semi-rigid portal frame corresponding to the M u, initial stiffness R ki and shape parameter n are set as constants. The ultimate moment capacity M u is varied from 0.3 to 0.8 M p referring to the plastic moment capacity of beam M p. R ki is non-dimensional using bending stiffness EI b/L b as follows:

In this study, non-dimensional initial connection stiffness ρ* = 0.125 is assumed according to Euro code connection classifications (Aristizabal-Ochoa 2011). Four nonlinear connection curves are used as shown in Fig. 4 and these parameters are listed in Table 1.

To precisely analyze the hysteretic damping effect of connection, viscous damping factor is assumed to be zero. An example of input acceleration wave is shown in Fig. 5, and amplitude α i and frequency f i are varied in numerical analyses.

Numerical results and discussions

Relationship between input acceleration amplitude and hysteretic damping effect

Table 2 compares natural frequency of the frame in case of three different conditions: rigid connections, pin connections, and linear semi-rigid connections with ρ* = 0.125. The natural frequency of frame is reduced with decrease in the connection stiffness and that it ranges between f 0 = 2.75 Hz for rigid frame and f 0 = 1.60 Hz for pin-connected frame as shown in the table.

Figure 6 shows a set of displacement response spectra in case of M = 0.3 M p and M u = 0.8 M p. The displacement and vibration frequency are normalized with reference to the value of static displacement δst and natural frequency f 0 = 2.65 (Hz) in Table 2 as δ/δ st and f i /f 0, respectively. δ st is calculated using seismic coefficient method with acceleration amplitude α i . From Fig. 6a, maximum displacement δ/δ st is about 40 in case of α i = 30 gal and M u = 0.8 M p. It is seen that even if input acceleration amplitude is about 30 gal, vibration of frame is influenced by hysteretic damping of connection because resonance response amplitude δ/δ st in case assuming linear connection stiffness is infinite theoretically. It is observed that δ/δ st is reduced according to increasing α i due to hysteretic damping effect of connections. From Fig. 6b, although the distribution characteristics of dynamic response spectra in case of M u = 0.6 M p are similar to those in case of M u = 0.8 M p, the values δ/δ st in case of M u = 0.6 M p are smaller than those in case of M u = 0.8 M p. The dynamic response spectrum in case of M u = 0.6 M p and α i = 120 gal is almost the same as that in case of M u = 0.8 M p and α i = 240 gal. These suggest that the smaller the M u the larger the hysteretic damping effect and smaller is the response spectrum.

Figure 6 also reveals that the resonance frequency is reduced by increasing α i and by reducing M u. This reduction is attributed to the decrease in tangent connection stiffness at maximum response amplitude of displacement and the increase in hysteretic damping factor.

This study adopted two simple methods to evaluate the hysteretic damping effect of connection: (1) a method identifying a damping constant h l at the resonance frequency by converting the vibration of frame into viscous damping vibration of single degree of freedom (SDOF) model; (2) a method evaluating a damping constant h h from dynamic response spectra by means of half power technique. Figure 7 shows relationship between input acceleration amplitude α i and damping constant h. This figure reveals that (1) damping constants obtained from SDOF model tend to be smaller than those obtained using half power technique; (2) the higher the acceleration results in lower ultimate moment capacity, the bigger is the damping constant h. However, in case of M u = 0.3 M p, damping constant h for α i = 220 gal is almost similar to that of α i = 320 gal.

Behavior of semi-rigid portal frame under large amplitude excitation

To investigate the dynamic response behavior of the frame subjected to a severe earthquake, the dynamic response analyses in case of M u = 0.3 M p are performed, varying input acceleration amplitude α i from 30 to 800 gal. Figure 6 reveals that with increasing α i , the resonance displacement δ/δ st has a tendency to decrease in the region of α i ≤ 320 gal and to increase in the region of α i > 320 gal. This suggests that hysteretic damping effect of connection is limited and may not be expected under the excitation with excessive input acceleration amplitude. In contrast, the resonance frequency of the frame decreases in increment of α i . If α i = 800 gal, then frequency f i /f 0 drops to 0.55. Moreover, the distribution characteristics of response spectra are very similar to those of SDOF model, if it is assumed that the restoring force has perfect elasto-plastic relationship.

Figure 8 shows typical examples of moment-rotation curves of connection and waves of connection moment during one period at the resonance frequency. In this figure, the abscissa of moment wave is phase angle ω i t. From this figure, the area of hysteretic loop of M − θ r curve increases in increment of α i . This means that the hysteretic damping effect of connection increases in increment of α i . In addition, configuration of moment wave is shifted from sine wave to rectangular one. However, allowing α i to increase by about 800 gal may cause the connection to behave like a pin, and spectra response can be extremely large.

Conclusions

In this study, the establishment of a seismic design procedure using dynamic analysis of steel frame is conducted. Following are the conclusions of this study:

-

1.

The resonance frequency of the frame must be reduced by increase in the input acceleration amplitude.

-

2.

The response spectra decrease due to hysteretic damping effect of connections.

-

3.

Higher acceleration magnitude results in lower ultimate moment capacity of connection and dynamic response is low.

-

4.

However, by increasing acceleration, the spectra have been increased because of zero stiffness of connections.

References

American Institute of Steel Construction (1993) Specifications of load and resistance factor design specification for structural steel buildings, 2nd edn. Chicago

Aristizabal-Ochoa ID (2011) Stability and non-linear second-order elastic analysis of beam and framed structures with semi-rigid connection using the cross method. Eng Struct 32(10):3258–3268

Barsan GM, Chiorean CG (1999) Computer program for large deflection elastoplastic analysis of semi-rigid steel frameworks. Comput Struct 72(6):669–711

Bhatti AQ (2013) Performance of viscoelastic dampers (VED) under various temperatures and application of magnetorheological dampers (MRD) for seismic control of structures. Mech Time Depend Mater (MTDM) 17(3):275–284. ISSN: 1385-2000

Bhatti AQ (2016) Application of dynamic analysis and modelling of structural concrete insulated panels (SCIP) for energy efficient buildings in seismic prone areas. Elsevier J Energy Build 128:164–177. ISSN: 0378-7788

Bhatti AQ (2016b) Scaled accelerographs for design of structures in Quetta, Baluchistan Pakistan. Int J Adv Struct Eng (IJASE) 8(4):401–410

Durucan C, Dicleli M (2010) Analytical study on seismic retrofitting of reinforced concrete buildings using steel braces with shear-link. Eng Struct 32:2995–3010

Hallquist JO (1999) LS-DYNA user’s manual. Livermore Software Technology Corporation, Livermore

Sekulovic M, Nefovska M (2008) Contribution to transient analysis of inelastic steel frames with semi-rigid connections. Eng Struct 30:976–989

Varum H, Teixeira-Dias F, Marques P, Pinto A, Bhatti AQ (2013) Performance evaluation of retrofitting strategies for non-seismically designed RC buildings using steel braces. Bull Earthq Eng 11(4):1129–1156

Vimonsatit V, Tangaranvong S, Tin-Loi F (2012) Second-order elastoplastic analysis of semirigid steel frames under cyclic loading. Eng Struct 4(5):127–136

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhatti, A.Q. Dynamic response characteristics of steel portal frames having semi-rigid joints under sinusoidal wave excitation. Int J Adv Struct Eng 9, 309–313 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40091-017-0167-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40091-017-0167-8