Abstract

Background

Post-malaria neurological syndrome (PMNS) is a rare self-limiting neurological complication that can occur after recovery from malaria, usually severe falciparum malaria. It is characterized by a myriad of neuropsychiatric manifestations including mild neurological deficit to severe encephalopathy. PMNS was first described in 1996 and since then there have been 48 cases reported in the English literature. We report another case of PMNS in a 24-year-old healthy male and present a review of the disease entity.

Method

We searched PMNS-related journal articles and case reports in the English literature, using PubMed and Google search engines. A total of forty-nine cases meeting the diagnostic criteria of PMNS were selected in this review.

Conclusion

PMNS is a rare complication of severe malaria that might be underreported. It can develop up to 2 months after clearance of parasitemia. Clinical features can be variable. Most cases are self-limited, but more severe cases may benefit from steroid therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Case history

A 24-year male presented with fever, confusion, dysarthria and grand mal seizure. He was recently diagnosed with severe falciparum malaria with multi-organ dysfunction, after being non-compliant with anti-malarial prophylaxis, while working for the Peace Corps in Togo in November 2017. He was treated with IV quinine with complete clearance of his parasitemia. He fully recovered but still required dialysis, and returned to the United States in December 2017. On the day of admission in late December, he arrived for scheduled dialysis and was found to be tachycardic which prompted him to be sent to an outside hospital, where he had an episode of confusion and dysarthria, after which he returned to his baseline mentation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was unremarkable. Next day, the patient had a grand mal seizure. A CT of the head was repeated which was again negative for any acute findings. No focal neurological deficit was observed following the seizure. However, the patient remained lethargic, agitated, and was not speaking or following commands, prompting the transfer to our hospital. On arrival, had a fever of 38.9 °C with sinus tachycardia of 130 beats/min, normal blood pressure and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 7. He was lethargic, wincing with sternal rub, not responding to verbal commands, and had no meningismus.

The patient’s white count was 15.3 × 103/µL (4–10 × 103/µL), hematocrit of 27.5%, with normal platelets (286 × 103/µL). His creatinine was 2.11 mg/dL, sodium 135 mmol/L, potassium 3.9 mmol/L and serum glucose 97 mg/dL. The total bilirubin and liver enzymes were normal. His human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein–Barr virus, dengue, West Nile virus and Lyme serology were negative, and rapid plasma regain (RPR) was non-reactive. Cerebral fluid (CSF) analysis revealed WBC of 75/µL with 91% lymphocytes, elevated protein of 65 mg/dL and glucose of 64 mg/dL. CSF Gram’s and acid-fast bacillus stains were negative. CSF polymerase chain reaction (PCR) pathogen panel (BiofireFootnote 1) for neurotropic bacteria, fungi and viruses was negative. CSF, blood, urine cultures and toxicology screening test were negative as well. CSF VDRL, Cryptococcal antigen and respiratory viral panel (RSVFootnote 2) were negative. Malaria smears were done on admission and the next day, and both were negative.

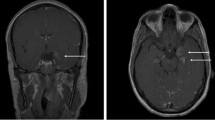

Chest X-ray, CT head and CT abdomen and thorax were unrevealing. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed nonspecific focus of signal abnormality in the posterior limb of the right internal capsule without evidence of acute infarction in this region.

The patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, acyclovir and Artemether–Lumefantrine, which were subsequently discontinued following negative laboratory results. A clinical diagnosis of PMNS was made and prednisone therapy was started at 1 mg/kg/day. His mentation began improving the next day, and steroids were tapered over 5 days with full recovery. Subsequent follow-up at 3 months revealed normal neurological examination.

Discussion

There are several neurological syndromes that can occur following complete recovery from malaria, in particular Plasmodium falciparum. These syndromes include PMNS, delayed cerebellar ataxia (DCA), acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) [1,2,3]. PMNS shares many characteristics of ADEM; hence, some authors describe PMNS as a form of ADEM.

PMNS is a predominantly self-limited condition, which can occur following severe falciparum malaria, not necessarily cerebral [1, 3]. Schnorf et al. [4] classified the syndrome into three categories based on clinical severity: a mild form characterized by isolated cerebellar ataxia or postural tremor; a diffuse, relatively mild encephalopathic form, associated with acute confusion or seizures; and a severe encephalopathy typified by motor aphasia, generalized myoclonus, postural tremor, and cerebellar ataxia.

The incidence of PMNS in patients after falciparum malaria can range from 0.7 to 1.8 per 1000 and it is 300 times more common in patients with severe rather than uncomplicated malaria [1]. The diagnosis of PMNS requires both proven symptomatic malaria infection with full initial clinical recovery and clearance of parasitemia following treatment, and the development of neurological or psychiatric symptoms within 2 months of acute illness [1].

We searched PMNS-related articles using PubMed and Google search engines and a total of forty nine cases, including our case, met the diagnostic criteria (Table 1). 24 (49%) infections were contracted in Asia, 24 (49%) in Africa, and 1(2%) in the Dominican Republic. Although most cases of P. falciparum occur in Africa, our results appear to be skewed by the large Vietnamese study [1]. There were 36 males and 13 females with male:female ratio of around 2.76:1. All the cases were preceded by falciparum malaria except one, which had P. vivax, reported from India. PMNS occurred mostly in patients who had preceding severe falciparum malaria. The mean parasitemia was 19.4% for 22 cases in which it was quantified. The common clinical features were confusion (50%), fever (47.7%), seizure (31.8%), speech abnormalities (18.2%), tremor (18.2%), behavioral abnormities (16%), impaired consciousness (16%), myoclonus (11.3%), ataxia (11.3%) and headache (6.8%). Less common features were psychosis (6.8%), catatonia (4.5%), hallucinations (6.8%), weakness (4.5%), dizziness (4.5%), mydriasis (4.5%), nystagmus (2.2%), paraplegia (2.2%), and somnolence (2.2%). The median duration of onset of PMNS in Nguyen’s study of 22 patients was 4 days; in 22 patients (out of 27 that these data were available for) the median duration was 14 days. However, the syndrome can occur anywhere from 0 to 60 days following clearance of parasitemia [1]. The median duration of symptoms was 13 days (range 3–25 days) excluding Nguyen’s study; in his study, it was 2.5 days (range 1–10).

The exact pathogenesis of PMNS is not known. Some authors suggest obstruction of cerebral microvasculature by parasitized red blood cell inducing cerebral hypoxemia [1, 7]. Hsieh et al. [7] described brain single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) findings with markedly decreased radioactivity. However, this mechanism is questionable as obstruction of microvasculature does not seem plausible due to the potentially long delay between malaria episode and PMNS. Another postulated hypothesis is immune mediated based on a positive response to corticosteroid therapy in some patients, and lagging of onset of PMNS symptoms after resolution of malaria symptoms [4]. An increment of serum and CSF concentrations of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-alpha, IL 2 and IL 6 has been described in some cases of delayed post-malaria cerebellar syndrome, which decreased following steroid therapy [24]. There is also some evidence of possible molecular mimicry, whereby antibodies to antigens expressed by certain strains of P. falciparum cross-react with antigens in the CNS [5]. However, a study by Siriez et al. [22] was unable to detect intrathecal IgG and specific P. falciparum antibodies in the CSF. Coinfection or reactivation of a viral infection capable of causing encephalitis has been suggested as another possible mechanism [4]. Schnorf et al. found elevated IgG and IgM antibodies against CMV and EBV in the serum but not the CSF of one of his patients, and positive IgG antibody against varicella zoster virus in the CSF and serum of the same patient albeit PCR repeatedly failed to detect genetic material of EBV, CMV, and VZV in the CSF. In fact, P. falciparum infection has been shown to induce polyclonal B cell activation and subsequent secretion of different antibodies, causing false-positive serological tests [25, 26]. Nguyen et al. implicated Mefloquine as a possible cause of PMNS since 17 of 22 patients (77%) were treated with Mefloquine. However, altogether 25 of 46 PMNS cases (54.3%) in our review were not taking Mefloquine.

CSF findings in PMS may be variable and may show risen opening pressure, pleocytosis and elevated protein. CSF analysis was performed in all cases except two, which revealed lymphocytic pleocytosis in two-thirds of the patients with an elevated protein in one-third.

MRI brain can be unremarkable or reveal some signal changes in various parts of brain. 10 out of 23 cases had abnormal MRI of brain. The abnormalities consisted of nonspecific findings with increased signal uptake in various regions of brain, including the periventricular areas, brain stem, thalamus, corona radiata, internal capsule, and cerebellum. In one case, there was inflammation of spinal cord along with brain stem and cerebellar peduncles while another patient had evidence of optic neuritis with cerebral edema [18, 23]. CT scans were normal in all cases in which MRI was abnormal.

PMNS usually does not require specific treatment. However, in severe cases steroids may help to hasten recovery [4, 7, 14]. Schnorf et al. observed two patients that continued to have worsening neurological symptoms until steroids were initiated, with rapid recovery [4]. Similarly, Hsieh et al. described persistent unsteadiness in their patient with PMNS for 2 weeks until the use of corticosteroids, which resulted in dramatic recovery. Overall in our literature review, 12 out of 48 were treated with steroids and all had rapid recovery within a few days of initiation of steroid therapy except two patients in which recovery was gradual. About half of the patients received oral prednisone initiated at 1 mg/kg/day and tapered over 7–10 days while most of the remaining patients received IV methyl prednisolone for 3–5 days. The neurological signs and symptoms of PMNS in most of patients resolved within days to weeks.

In conclusion, PMNS is a rare complication of severe malaria that might be underreported. It can develop up to 2 months after clearance of parasitemia. Clinical features can be variable. Most cases are self-limited but more severe cases may benefit from steroid therapy. In patients with recent history of malaria that present with neuropsychiatric symptoms, PMNS should be strongly considered.

Notes

CSF pathology panel (Biofire) includes E. coli K1, H. influenza, Listeria monocytogenes, N. meningitides, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Cytomegalovirus, Enterovirus, herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, human herpes virus 6, human Parechovirus, varicella zoster virus, Cryptococcus neoformans/gattii.

Repiratory viral panel (RVP) influenza A & B viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, Human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus 1–4, adenovirus, rhinovirus/Enterovirus, Coronavirus HKU1, NL63, OC43, and 229E, Bordetella pertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlymadia pneumoniae.

References

Nguyen TH, Day NP, Ly VC, et al. Post-malaria neurological syndrome. Lancet. 1996;348:917–21.

O’Brien MD, Jagathesan T. Lesson of the month 1: post-malaria neurological syndromes. Clin Med. 2016;16:292–3.

Mohsen AH, McKendrick MW, Schmid ML, et al. Postmalaria neurological syndrome: a case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:388–9.

Schnorf H, Diserens K, Schnyder H, et al. Corticosteroid responsive postmalaria encephalopathy characterized by motor aphasia, myoclonus, and postural tremor. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:417–20.

Lawn SD, Flanagan LK, Wright SG, et al. Postmalaria neurological syndrome: two cases from the Gambia. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:e29–31.

Falchook GS, Malone CM, Upton S, Shandera WX. Post malaria neurological syndrome after treatment of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:e22-24.

Hsieh CF, Shih PY, Lin RT. Postmalaria neurological syndrome: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2006;22:630–5.

Palmieri F, Petrosillo N, Paglia MG, et al. Genetic confirmation of quinine-resistant plasmodium falciparum malaria followed by postmalaria neurological syndrome in a traveler from Mozambique. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:5424–6.

Zambito Marsala S, Ferracci F, Cecotti L, Gentile M, Conte F, Candeago RM, Marchini C. Post malaria neurological syndrome: clinical and laboratory findings in one patient. Neurol Sci. 2006;27:442–4.

Silva-Pinto A, Costa A, Alves J, Silva NN, Abreu C, Santos L, Sarmento A. Post-malaria neurological syndrome: report of 3 cases from a Portuguese malaria reference centre. 2017. https://www.escmid.org/escmid_publications/escmid_elibrary. Accessed 24 Apr 2017

van der Wal G, Verhagen WI, Dofferhoff AS. Neurological complications following plasmodium falciparum infection. Neth J Med. 2005;63:180–3.

Mizuno Y, Kato Y, Kanagawa S, et al. A case of postmalaria neurological syndrome in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2006;12:399–401.

Prendki V, Elziere C, Durand R, et al. Post-malaria neurological syndrome—two cases in patients of African origin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:699–701.

Markley JD, Edmond MB. Post-malaria neurological syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Travel Med. 2009;16:424–30.

Matias G, Canas N, Antunes I, Vale J. Post-malaria neurologic syndrome. Acta Med Port. 2008;21:387.

Odawara T, Matsumura T, Maeda T, Washizaki K, Iwamoto A, Fujii T. A case of post-malarial neurological syndrome (PMNS) after treatment of falciparum malaria with artesunate and mefloquine. Trop Med Health. 2009;37:125–8.

Rakotoarivelo RA, Razafimahefa SH, Andrianasolo R, Fandresena FH, Razanamparany MM, Randria MJ, Rapelanoro Rabenja F. Post-malaria neurological syndrome complicating a Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Madagascar. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 2012;105:199–201.

Pace AA, Edwards S, Weatherby S. A new clinical variant of the post-malaria neurological syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2013;334:183–5.

Mittal S, Misri ZK, Rakshith KC, Mittal S. Post malarial neurological syndrome: an uncommon cause. J Neuroinfect Dis. 2015;S1:004.

Costa A, Silva-Pinto A, Alves J, et al. Postmalaria neurologic syndrome associated with neurexin-3α antibodies. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4:e39.

Chiabi A, Bogne JB, Nguefack S, Mah E, Siyou H, Djimafo A, Defo A, Angwafo F. Post malaria neurological syndrome in a Cameroonian child after a Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection. J Public Health Emerg. 2017;1:6.

Siriez JY, Prendki V, Dauger S, Michel JF, Blondé R, Faye A, Houzé S, Mercier JC. Post-malaria neurologic syndrome: a rare pediatric case report. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36:1217–9.

Almuntaser S, Costello A, Lynch B, et al. G320(P) post-malaria neurological syndrome: the first Irish paediatric case. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103:A130.

Senanayake N, de Silva HJ. Delayed cerebellar ataxia complicating falciparum malaria: a clinical study of 74 patients. J Neurol. 1994;241:456–9.

Donati D, Zhang LP, Chêne A, Chen Q, Flick K, Nyström M, Wahlgren M, Bejarano MT. Identification of a polyclonal B-cell activator in Plasmodium falciparum. Infect Immun. 2004;72:5412–8. Erratum in: Infect Immun. 2005;73:7790.

Adu D, Williams DG, Quakyi IA, Voller A, Anim-Addo Y, Bruce-Tagoe AA, Johnson GD, Holborow EJ. Anti-ssDNA and antinuclear antibodies in human malaria. Clin Exp Immunol. 1982;49:310–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yadava, S.K., Laleker, A. & Fazili, T. Post-malaria neurological syndrome: a rare neurological complication of malaria. Infection 47, 183–193 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-019-01267-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-019-01267-9